1. Overview

Emperor Tenmu (天武天皇Tenmu tennōJapanese, c. 631 CE - October 1, 686) was the 40th Emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. His reign, from 673 until his death in 686, marked a pivotal period in early Japanese history, often referred to as the late Asuka period or the Hakuhō period. Tenmu ascended to the throne following his decisive victory in the Jinshin War of 672, a civil conflict against his nephew, Emperor Kōbun.

During his reign, Emperor Tenmu initiated extensive political, administrative, and cultural reforms aimed at consolidating imperial power and centralizing governance. He is credited with establishing the foundational framework for the Ritsuryō system, a legal and administrative code based on Chinese models, and reorganizing the clan system through the `kabane` reform and the establishment of the Eight-Ranked Titles. Tenmu's policies also extended to the economy, military, and foreign relations, where he favored the Korean kingdom of Silla while severing diplomatic ties with the Tang dynasty of China. He strategically utilized religious structures, promoting both Shinto (especially the Ise Grand Shrine) and Buddhism to bolster imperial authority. Furthermore, he commissioned monumental historical works like the `Nihon Shoki` and `Kojiki`, which laid the groundwork for Japanese historiography and reinforced the imperial lineage. His rule is characterized by a strong, centralized imperial authority and a significant shaping of early Japanese state and culture.

2. Name and Titles

2.1. Given Name and Posthumous Names

Emperor Tenmu's birth name was Prince Ōama (大海人皇子Ōama no ŌjiJapanese). This name is believed to derive from the `Ōama` (凡海) clan, which belonged to the `Kaifu` (海部) family and served as `Tomono miyatsuko` (伴造), who were responsible for his upbringing during his childhood. Although the `Nihon Shoki` does not explicitly state this, it is inferred from the eulogy given by `Ōama no Arakama` (凡海麁鎌) at Tenmu's funeral, which mentioned his `mibu` (壬生), or upbringing.

His Japanese-style posthumous name (和風諡号Wafū ShigōJapanese) is `Amanonunahara-Oki-no-Mahito-no-Sumeramikoto` (天渟中原瀛真人天皇Amanonunahara-Oki-no-Mahito-no-SumeramikotoJapanese). The term `Oki` (瀛) refers to `Yíngzhōu` (瀛洲), one of the three mythical divine mountains in the East according to Taoist beliefs (the other two being `Penglai` and `Fangzhang`). `Mahito` (真人) denotes a superior Taoist master or "true person." Both `Oki` and `Mahito` are deeply rooted in Taoist terminology, suggesting a strong influence of Taoist thought on Tenmu's self-perception and imperial ideology.

His Chinese-style posthumous name, `Tenmu Tennō` (天武天皇), was presented by Ōmi no Mifune during the Nara period, following the tradition of naming emperors. The scholar Mori Ōgai suggested that the name `Tenmu` might derive from the Chinese classic `Guoyu` (國語), specifically the phrase "Heaven's affairs are martial (武), Earth's affairs are civil (文), and the people's affairs are loyalty and trustworthiness (忠信)." Other theories propose that `Tenmu` was inspired by Emperor Wu of Han or King Wu of Zhou, implying a ruler who establishes a new dynasty by overthrowing a corrupt one.

2.2. Titles and National Name

Emperor Tenmu is historically significant as the first monarch of Japan to whom the title `Tennō` (天皇EmperorJapanese) was assigned contemporaneously, rather than retrospectively by later generations. Some scholars suggest that `Tennō` was initially a unique honorific used exclusively for Tenmu, reflecting his extraordinary charisma and the profound impression he made on his people after his victory in the Jinshin War. This title was later adopted as the official designation for subsequent monarchs to inherit his powerful charisma. Evidence for this theory includes instances in the `Nihon Shoki` where the term `Tennō` (天皇) in the `Jitō` chronicle refers specifically to Emperor Tenmu, rather than Empress Jitō.

Furthermore, Emperor Tenmu is widely believed to be the first ruler to officially adopt `Nippon` (日本JapanJapanese) as the national name. This adoption is linked to the compilation of the `Nihon Shoki` and the `Asuka Kiyomihara Code`, where the name was likely formally incorporated. The name `Nippon`, meaning "origin of the sun" or "land of the rising sun," is thought to embody the concept of a nation centered around the sun, aligning with the imperial myth that the Japanese monarchs are descendants of the sun goddess, Amaterasu Ōmikami. This choice of national name served to reinforce the divine lineage and legitimacy of the imperial family.

3. Early Life and Rise to Power

3.1. Birth and Childhood

Emperor Tenmu was born to Emperor Jomei and Empress Kōgyoku (who later reigned again as Empress Saimei). The exact year of his birth is not recorded in the `Nihon Shoki`, which is unusual for a monarch. Medieval chronicles and genealogies, such as `Ichidai Yōki`, `Honchō Kōin Jōunroku`, and `Kōnen Dairyakuki`, provide varying posthumous ages for Tenmu, leading to different calculations for his birth year, ranging from 614 to 640.

One prominent theory, based on his recorded death at 65 years old in `Ichidai Yōki`, suggests a birth year of 622 or 623. This would make him older than his brother, Emperor Tenji, whose birth year is recorded as 626 in the `Nihon Shoki`. This discrepancy led some scholars, particularly those outside mainstream historical academia, to propose that Tenmu was in fact older than Tenji, or even their half-brother, `Prince Aya` (漢皇子), born to Empress Kōgyoku before her marriage to Emperor Jomei. However, mainstream historians generally dismiss these theories, as medieval sources consistently depict Tenji as older than Tenmu. The prevailing view among most historians is that Tenmu's precise birth year remains unknown.

The following table summarizes the birth years and ages at key events for Emperor Tenji and Emperor Tenmu as presented in various historical sources:

| Source | Emperor Tenji's Birth Year | Emperor Tenmu's Birth Year | Age at Isshi Incident | Age at Tenji's Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nihon Shoki | 626 | Unknown | Tenji 20, Tenmu -- | Tenji 46, Tenmu -- |

| (Tenmu 56-year-old death theory) | 626 | 631 | Tenji 20, Tenmu 15 | Tenji 46, Tenmu 41 |

| Ichidai Yōki | 619 | 622 | Tenji 27, Tenmu 24 | Tenji 53, Tenmu 50 |

| Ninjū-kyō | 614 | Unknown | Tenji 32, Tenmu -- | Tenji 58, Tenmu -- |

| Kōfuku-ji Ryaku Nendaiki | 631 | 640 | Tenji 15, Tenmu 6 | Tenji 41, Tenmu 32 |

| Jinnō Shōtōki, Nyozuin Nendaiki | 614 | 614 | Tenji 32, Tenmu 32 | Tenji 58, Tenmu 58 |

| Jinnō Shōtōroku, Honchō Kōin Jōunroku | 614 | 622 | Tenji 32, Tenmu 24 | Tenji 58, Tenmu 50 |

| Kōnen Dairyakuki | 614 | 623 | Tenji 32, Tenmu 23 | Tenji 58, Tenmu 49 |

3.2. Siblings and Family

Emperor Tenmu was the youngest son of Emperor Jomei and Empress Kōgyoku (later Empress Saimei). He was the younger brother of Emperor Tenji (Prince Naka-no-Ōe) and Princess Hashihito. His father, Emperor Jomei, died when Tenmu was young, and he was primarily raised under the guidance of his mother, Empress Saimei.

During the reign of his elder brother, Emperor Tenji, Tenmu was compelled to marry several of Tenji's daughters to strengthen political ties between the two brothers. These nieces included Princess Uno-no-sarara (later Empress Jitō), Princess Ōta, Princess Ōe, and Princess Niitabe. He also had other consorts whose fathers were influential courtiers, such as Fujiwara no Hikami-no-iratsume, Fujiwara no Ioe-no-iratsume, Soga no Ōnu-no-iratsume, Munakata no Amako-no-iratsume, and Shishihito no Kajihime-no-iratsume.

A notable episode involves Princess Nukata, who was initially Tenmu's consort and bore him Princess Tōchi. Later, Princess Nukata became a consort of Emperor Tenji. This "love triangle" is sometimes cited as a potential source of discord between the two brothers, though historical opinions on its significance vary. During Empress Saimei's expedition to Kyushu to aid Baekje, Prince Ōama accompanied her with his wives. Princess Ōta gave birth to Princess Ōku in Ōkuno-umi (present-day eastern Okayama Prefecture) on January 8, 661, and Prince Ōtsu is said to have been born in Naotsu (present-day Fukuoka) in Kyushu.

3.3. Reign of Emperor Tenji and Succession Disputes

After Empress Saimei's death, Prince Naka-no-Ōe (later Emperor Tenji) governed as `Chinsō` (称制), a regency without formally ascending the throne. In 664, Prince Ōama, on Naka-no-Ōe's orders, announced the implementation of the Twenty-Six Cap Ranks system, recognized `Ujigami` (clan heads), and established `Minobe` (民部, people under state control) and `Kabe` (家部, people under clan control).

In 668, Naka-no-Ōe formally ascended as Emperor Tenji. The `Nihon Shoki` states that Prince Ōama was appointed Crown Prince (`Tōgū`) at this time. However, this appointment is only mentioned in the `Nihon Shoki`'s section on Tenmu's pre-enthronement history and not in Tenji's own chronicle. In Tenji's chronicle, Ōama is referred to as `Ō-ō-irodo` (大皇弟, Great Imperial Younger Brother) or `Tōgū Tai-ō-irodo` (東宮太皇弟, Crown Prince and Great Imperial Younger Brother). Some scholars believe Ōama was indeed the Crown Prince, while others argue these titles were honorifics or literary embellishments to legitimize Tenmu's later actions in the Jinshin War, suggesting he was not formally designated as heir. Regardless, it is acknowledged that Prince Ōama held a highly significant position within Emperor Tenji's court.

Tensions between the brothers were evident. The `Tōshi Kaden` (藤氏家伝), a Fujiwara clan history, recounts an incident where Prince Ōama, in a fit of rage during a banquet, thrust a long spear through the floorboards in front of Emperor Tenji, who then attempted to kill him, only to be restrained by Fujiwara no Kamatari. This event is believed to have occurred around 668.

In 671, Emperor Tenji appointed his son, Prince Ōtomo, as `Daijō-daijin` (太政大臣, Chancellor). This position oversaw national affairs, a role that had previously overlapped with Prince Ōama's responsibilities. While the `Nihon Shoki` notes that the "Crown Prince and Great Imperial Younger Brother" (referring to Ōama) continued to implement cap ranks and laws, an alternative account states that Prince Ōtomo performed these duties. This appointment of Prince Ōtomo, who had weaker political support from his maternal relatives, signaled Emperor Tenji's strong intention for him to succeed to the throne, effectively sidelining Prince Ōama. Feeling his life was in danger, Prince Ōama voluntarily resigned his position as Crown Prince and became a monk. He then retreated to the mountains of Yoshino in Yamato Province, officially for seclusion, taking with him his wife Princess Uno-no-sarara and their sons, but leaving his other consorts in the capital, Ōmi-kyō (modern-day Ōtsu).

3.4. Jinshin War

A year later, in 672, Emperor Tenji died, and Prince Ōtomo ascended to the throne as Emperor Kōbun. On June 22, 672, Prince Ōama, from his retreat in Yoshino, decided to raise an army. He dispatched envoys, including Murakuni no Oyori, to Mino Province (modern-day Gifu Prefecture). Two days later, he followed with a small retinue. In Mino, his `Yumokurei` (湯沐令, official in charge of a tax-exempt territory), Takami no Honji, had already raised forces. Ōama's retainers included local powerful clans from Mino and Owari Province.

Prince Ōama's strategy involved blocking the Fuwa Road, a critical route that connected the Ōmi court with the eastern provinces, thereby cutting off communications. He sent messengers to the eastern regions, including Shinano Province (Higashiyama) and Owari Province (Tōkai), to rally support. In the Yamato Basin, Ōtomo no Fukei launched a surprise attack, seizing the old capital of Yamato-kyō in Asuka. The Ōmi court faced internal turmoil: Kume no Shiokago, the governor of Kawachi Province, was killed for attempting to defect to Ōama's side, and Yamabe Ō, a general from Ōmi, was also killed. The Ōmi local lord Haneda no Yakuni also switched allegiance to Ōama.

Ōama's forces, numbering in the tens of thousands, converged at Fuwa. He then dispatched armies in two directions: towards Ōmi and Yamato. The Ōmi-bound army advanced along the eastern shore of Lake Biwa, repeatedly defeating the imperial forces. The decisive battle took place in the northwestern part of Mino, near modern-day Sekigahara, Gifu, in what became known as the Jinshin War. On July 23, Ōama's army emerged victorious, and Emperor Kōbun committed suicide, bringing an end to the civil war.

Historians have debated the chronology of succession during this period. Post-Meiji chronology suggests that Emperor Tenji designated his son as heir in 671, and Emperor Kōbun acceded after Tenji's death. Then, in 672, after Kōbun's death, Prince Ōama received the succession and acceded as Emperor Tenmu. However, pre-Meiji chronology often viewed Prince Ōtomo as a mere usurper, asserting that after Tenji's death in 671, Prince Ōama rightfully received the succession and acceded to the throne.

4. Reign (673-686)

4.1. Enthronement and Capital

After his victory in the Jinshin War, Emperor Tenmu remained in Mino for some time to manage post-war affairs. In September 672, he returned to the old capital of Asuka, first entering Shimamiya (島宮) and then Okamoto Palace (岡本宮), which had previously served as the imperial residence for Emperor Jomei and Empress Saimei. In the same year, he ordered the construction of new palace buildings. Two months before his death, on July 20, 686, his palace complex was officially named `Asuka Kiyomihara Palace` (飛鳥浄御原宮Asuka Kiyomihara-no-miyaJapanese). Archaeological findings suggest that this corresponds to the Asuka Palace (traditional Asuka Itabuki Palace) Phase III-B, which primarily utilized the existing Okamoto Palace structures while adding the `Ebinoko-kaku` (エビノコ郭), a new large hall believed to have functioned as the `Daigokuden` (大極殿, Great Hall of State).

On February 27, 673, Emperor Tenmu was formally enthroned at Asuka Kiyomihara Palace. He elevated Princess Uno-no-sarara to the position of Empress. His reign, lasting 14 years (13 years from his enthronement), is often grouped with that of his successor, Empress Jitō, as the `Tenmu-Jitō` period, as Empress Jitō largely continued and completed Tenmu's policies. This era is culturally recognized as the Hakuhō period.

4.2. Political and Administrative Reforms

Emperor Tenmu's reign was characterized by a strong drive towards political and administrative centralization, laying the groundwork for the future Ritsuryō system.

4.2.1. Imperial Rule and Centralization

Emperor Tenmu established a highly centralized form of imperial rule. He did not appoint a `Daijin` (大臣, Minister) during his reign, instead directly overseeing state affairs, including judicial and military matters. This decision effectively concentrated power solely in the hands of the Emperor, a rare instance of such direct imperial control in Japanese history.

A distinctive feature of his administration was the practice of `kōshin seiji` (皇親政治kōshin seijiJapanese, "imperial family politics"), where members of the imperial family were appointed to key government positions. While these imperial princes held important roles, the ultimate authority remained with the Emperor himself, who was not constrained by their counsel. This concentration of power, coupled with his strong charisma, elevated the imperial institution to an unprecedented level of autocracy in ancient Japan. However, this autocratic rule had its limitations; unlike in China, there was no widespread promotion of commoners to high office, and even meritorious figures from the Jinshin War who were of regional origin remained subordinate to the traditional aristocracy. This suggests that even at its peak, imperial autocracy in Japan operated within the constraints of a deeply entrenched aristocratic system. Emperor Tenmu also deliberately limited the promotion of officials to higher ranks (above `Daikin-ge` or `Jikikō-ni`) to prevent the emergence of powerful vassals who could challenge his authority. Instead, he focused on promoting lower-ranking officials to stabilize his regime with loyal bureaucrats.

4.2.2. Kabane Reform and Eight-Ranked Titles

Emperor Tenmu undertook a significant restructuring of the `kabane` (姓kabaneJapanese), the hereditary title system that defined the social rank and duties of clans. This reform aimed to integrate powerful clans into the imperial administrative order and solidify state control.

In 684, he established the `Yakusa no Kabane` (八色の姓Yakusa no KabaneJapanese, "Eight-Ranked Titles"), a comprehensive reorganization of the existing clan structure. This new hierarchy reclassified clans based on their proximity to the imperial bloodline and their loyalty to Tenmu, particularly acknowledging those who had supported him during the Jinshin War. The highest rank, `Mahito` (真人), was reserved for descendants of the imperial family. Traditional powerful clan titles like `Omi` (臣) and `Muraji` (連), which were formerly the highest `kabane`, were devalued in this new system. `Omi` clans were reclassified as `Ason` (朝臣), and `Muraji` clans as `Sukune` (宿禰). The other ranks included `Imiki` (忌寸), `Michinoshi` (道師), `Omi` (臣), `Muraji` (連), and `Inagi` (稲置). This reform effectively integrated the aristocracy into the state bureaucracy, ensuring that their status was derived from and dependent on imperial favor, rather than solely on their traditional hereditary power.

4.2.3. Ritsuryō System and Legal Codes

A monumental undertaking of Emperor Tenmu's reign was the initiation of the `Ritsuryō` (律令) legal system. On February 25, 681, he issued an imperial edict to begin the compilation of `Ritsuryō` codes and to reform existing legal practices. This ambitious project involved numerous officials working collaboratively.

However, the compilation was not completed during Tenmu's lifetime. It was eventually finished and promulgated as the `Asuka Kiyomihara Decree` (飛鳥浄御原令Asuka Kiyomihara-ryōJapanese) by Empress Jitō on June 29, 689, three years after Tenmu's death. While the precise contents of the `Asuka Kiyomihara-ryō` are not fully known, it is understood to have laid the fundamental groundwork for the later, more comprehensive `Taihō Code` (701) and `Yōrō Code` (718). The `Asuka Kiyomihara-ryō` established the basic framework for the `Ritsuryō` official system, including administrative structures, legal principles, and civil service regulations. Scholars widely acknowledge that the core principles and practical significance of the `Ritsuryō` system were largely established under Tenmu's reign, marking a crucial step towards a centralized bureaucratic state in Japan.

4.3. Economic and Social Policies

Emperor Tenmu implemented various economic and social policies aimed at strengthening the imperial state and controlling resources.

4.3.1. Currency and Taxation

The first Japanese currency, `Fuhonsen` (富本銭FuhonsenJapanese), is believed to have been minted during Emperor Tenmu's reign. These copper and antimony coins, found at the Asukaike (飛鳥池) site, date to the late 7th century. While some theories suggest `Fuhonsen` were primarily for magical purposes rather than circulation, or that earlier un-inscribed silver coins (`Mumon-ginsen`) existed, modern archaeological findings and scholarly interpretations increasingly support `Fuhonsen` as an early form of circulating currency. The `Haedong Jegukgi` (海東諸國紀Korean) notes that in 683 (Tenmu 12th year), carts were first made, and copper coins were introduced to replace silver coins.

Regarding taxation, Tenmu reformed the system of `fuko` (封戸fukoJapanese, stipend households), which provided income to imperial family members, nobles, and temples. He sought to prevent the formation of strong local ties between `fuko` recipients and the households by relocating the tax sources of `fuko` from western provinces to eastern provinces in 676. In 679, he granted `fuko` to imperial family members and ministers of `Shōkin` rank and above, completing the transition to the new system. He also ordered investigations into temple `fuko` in 679 and limited their tenure to 30 years in 680. Although an edict in 682 ordered the return of `fuko` to the state, the system continued, suggesting a reform in its management rather than outright abolition.

4.3.2. Land and Labor Policies

Emperor Tenmu actively sought to dismantle the private control of land and people by powerful clans and religious institutions, asserting the state's direct authority. In 675, he issued an edict to reclaim `be` (部曲, private land and people) that had been recognized since Emperor Tenji's reign (664), as well as private mountains, swamps, islands, forests, and ponds owned by imperial family members, nobles, and temples. This move aimed to centralize control over resources and labor.

His policies aimed to transition from private clan control to a system where compensation was granted to individuals based on their official rank, position, or merit. While `fuko` existed before Tenmu, his reign saw a significant shift in their implementation to sever the master-servant relationships that developed when `fuko` were tied to specific locations for extended periods.

Furthermore, in 676, when faced with famine and requests from `Shimotsuke Province` officials to allow the sale of children due to crop failure, the court refused, demonstrating a policy aimed at protecting the populace and preventing the exploitation of labor, even during times of hardship.

4.3.3. Animal Protection Laws

On April 17, 675, Emperor Tenmu issued the first "meat consumption ban" (肉食禁止令). This decree prohibited the consumption of meat from domesticated animals such as cattle, horses, dogs, monkeys, and chickens, specifically during the period from April 1 to September 30 each year. This ban was not a complete prohibition of meat consumption, as it was limited to certain animals and a specific season (corresponding to the rice-growing period). It also did not prohibit the hunting and consumption of wild animals like deer and boar, which were considered agricultural pests.

The primary purpose of this law was to promote agriculture and protect useful livestock, particularly cattle and horses, which were essential for farming. By restricting the consumption of these animals during the crucial farming season, Tenmu aimed to ensure stable tax revenues based on rice cultivation. This policy, along with similar decrees in later periods, gradually contributed to the cultural perception of meat consumption as impure or defiling in Japan, especially in relation to rice cultivation.

4.4. Military Policy

Emperor Tenmu implemented significant military reforms to strengthen the imperial state's defense capabilities and ensure internal security. He made the arming of officials and the populace a special policy.

In 675, he mandated that all officials, from imperial princes to those of the lowest court rank (`Sho-i`), be armed. This was followed by an inspection of weapons in 676. He also ordered military exercises, such as horse racing at `Tokumi Station` in 679 and mounted archery at `Nagara Shrine` in 680, for officials of `Daisan-i` rank and below. In 684, he re-emphasized the importance of military affairs, stating that "the essence of governance is military" and ordering civil and military officials, as well as the general populace, to practice military tactics and horsemanship, threatening punishment for non-compliance. In 685, he inspected the weapons of laborers in the capital and its surrounding provinces (`Kinai`). This policy of arming officials was a unique characteristic of the Tenmu-Jitō period, not seen before or after.

To enhance defenses, in 679, he established barriers at `Tatsuta` Mountain and `Ōsaka` Mountain and ordered the construction of outer walls around `Naniwa-kyō`. In 683, he commanded all provinces to study battle formations. In 685, he ordered the storage of military command tools and large weapons at `kōri` (評) offices. While the `gun-dan` (軍団), the main military units under the later `Ritsuryō` system, were not yet established, the arming of officials and the storage of equipment at `kōri` offices suggest a nascent military organization. Scholars debate the nature of the national military system at the time, proposing theories such as `Hyōsei-gun` (military forces led by `Hyō-zō` and `Hyō-toku` officials) or the continuation of traditional `Kunizukuri-gun` (military forces led by `Kunizukuri` officials).

4.5. Foreign Policy

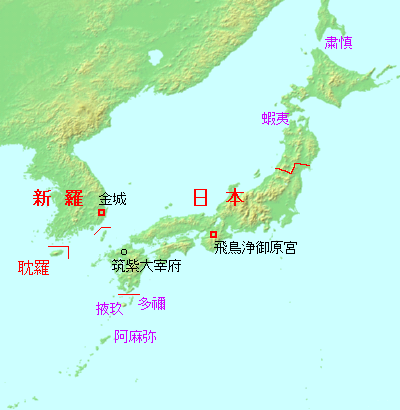

Emperor Tenmu's foreign policy was shaped by the geopolitical situation following the Battle of Baekgang (663), where Japan and Baekje were defeated by Tang China and Silla. After the unification of the Korean Peninsula by Silla in 676, Tenmu adopted a policy that favored Silla while severing diplomatic relations with the Tang Dynasty of China. This decision was evidently aimed at maintaining good relations with Silla, which had become the dominant power on the peninsula.

During his reign, there were frequent exchanges of envoys with Silla. Additionally, envoys from `Tamna` (耽羅Korean), located on Jeju Island, visited Japan. In 682, gifts were bestowed upon people from the Southwest Islands, including 多禰TaneJapanese (Tanegashima), 掖玖YakuJapanese (Yakushima), and 阿麻弥AmamiJapanese (Amami Ōshima). In the northeast, Tenmu engaged with the 蝦夷EmishiJapanese, granting cap ranks to 蝦夷EmishiJapanese from 陸奥MutsuJapanese Province in 682 and authorizing the establishment of `kōri` (評) in the 越EchigoJapanese Province for 蝦夷EmishiJapanese like Ikokina.

Despite his pro-Silla stance, Tenmu did not discriminate against immigrants from Baekje. He bestowed court ranks upon Baekje individuals such as Sataku Shōmei in 673 and Kudara no Konikishi Saishō in 674. In 685, he granted 30 `fuko` households to the Baekje monk Jōki. Furthermore, from 672 to 681, he exempted Korean immigrants from taxation, extending this exemption to those who had arrived as children in 681. This suggests a pragmatic approach to foreign-born individuals, focusing on their integration and contribution rather than their origin.

4.6. Religious Policies

Emperor Tenmu's reign saw significant developments in religious policy, marked by a deliberate integration of indigenous Shinto practices with imported Buddhism and Taoism to strengthen imperial authority.

4.6.1. Shinto and State Shinto

Emperor Tenmu placed great emphasis on traditional Japanese kami worship, elevating some local rituals to national importance. While not rejecting foreign cultures, his efforts were distinct in their focus on systematizing indigenous beliefs and integrating local deities into a framework centered around the imperial family's ancestor goddess, Amaterasu Ōmikami. This process led to the formation of an ancient State Shinto, where local shrines and rituals, in exchange for imperial protection, came under state control.

He particularly emphasized the Ise Grand Shrine, dedicated to Amaterasu, establishing its preeminent position as the highest shrine in Japan. During the Jinshin War, Prince Ōama had performed a distant worship of Amaterasu by bowing towards the Ise Grand Shrine from the banks of the `Ota River` in Ise. After his enthronement, he sent his daughter, Princess Ōku, to serve as the first `Saiō` (斎王), an unmarried imperial princess who served as high priestess at Ise. In 675, his daughters Princess Tōchi and Princess Abe (later Empress Genmei) also visited the shrine. The `Shikinen Sengū` (式年遷宮), the system of rebuilding the Ise Grand Shrine every 20 years, is believed to have been initiated by Tenmu, either in 685 or 688. Some scholars also theorize that Tenmu was instrumental in establishing Amaterasu Ōmikami as the central imperial deity, possibly by merging local sun worship with the imperial ancestral cult, and that he relocated the Ise Grand Shrine to its current location along the Isuzu River.

Other Shinto practices promoted by Tenmu include sending Prince Osakabe to `Isonokami Shrine` in 674 to polish its sacred treasures. In 675, he dispatched officials to worship the wind god at `Tatsuta Shrine` and the great `Imikami` at `Hirose Shrine`, establishing a tradition of imperial envoys to these shrines. The annual `Kinensai` (祈年祭), a harvest prayer festival, is also believed by some to have originated during his reign.

4.6.2. Buddhism Promotion

Emperor Tenmu was a fervent patron of Buddhism, a faith he had personally embraced by becoming a monk before his enthronement. His promotion of Buddhism was often intertwined with state protection (`Gokoku Bukkyō`, 護国仏教).

In 673, he initiated a massive project to transcribe the entire Buddhist canon (`Issai-kyō`) at `Kawara-dera` (川原寺). In 676, he dispatched envoys nationwide to preach the `Konkōmyō-kyō` (金光明経, Golden Light Sutra) and `Ninnō-kyō` (仁王経, Benevolent Kings Sutra), and in 679, he ordered the preaching of the `Konkōmyō-kyō` in 24 temples in Yamato-kyō and within the palace. The `Konkōmyō-kyō` asserts that the monarch is a child of heaven, protected by deities, and thus justified in ruling the populace, aligning with the concept of the Emperor as a living god (`arahitogami`) descended from Amaterasu Ōmikami. These initiatives were primarily aimed at state protection rather than individual salvation.

He also supported temple construction. In 673, he appointed officials to oversee the relocation of `Baekje-ō-dera` (百済大寺), founded by Emperor Jomei, to `Takachi` (高市), renaming it `Takachi-ō-dera` (高市大寺). In 680, he prayed for his Empress's recovery by commissioning the construction of `Yakushi-ji` (薬師寺). He also sought Buddhist prayers for his own illness. In 685, he issued an edict encouraging every household to build a `butsudan` (仏舎, Buddhist altar) for worship and offerings, signifying a broader dissemination of Buddhist practice among the populace. This period saw a proliferation of `ujidera` (氏寺, clan temples) throughout the country, suggesting significant state support.

However, Tenmu's patronage came with strict state control. He aimed to subordinate Buddhism to the state, requiring monks and nuns to focus on prayers for the Emperor and the nation. In 675, he reclaimed mountains and ponds granted to temples, and in 679, he revised `fuko` for temples, asserting state control over their income. He revived the `Sōgō` (僧綱) system, re-establishing `Sōjō` (僧正, Director-General of Monks) and `Sōzu` (僧都, Supervisor of Monks) to oversee monastic affairs. His administration also regulated monastic conduct and attire, placing all temples and clergy under strict state supervision. Some historians argue that Tenmu's understanding of Buddhism was superficial, focused on worldly benefits and state protection rather than individual enlightenment or the core tenets of self-negation and altruism.

4.6.3. Influence of Taoism

Taoist elements were notably prominent in Emperor Tenmu's religious worldview. The concept of the Emperor as a divine being, as expressed in poems like "Our Sovereign, a god," is sometimes interpreted as referring to a Taoist deity, a higher being than a mere immortal. The highest rank in the `Yakusa no Kabane` system was `Mahito` (真人), a term for a high-ranking immortal in Taoism. Tenmu's own Japanese-style posthumous name, `Amanonunahara-Oki-no-Mahito-no-Sumeramikoto`, translates to "True Person of the Clear Sky and the Ocean Isle," with `Oki` referencing `Yíngzhōu`, a Taoist mythical island. This suggests that Tenmu saw himself as a supreme Taoist deity.

His expertise in `Tenmon Tonkō` (天文遁甲, astronomy and divination), as noted in the `Nihon Shoki`, was a Taoist skill. The octagonal shape of his tomb (`Hakkaku-fun`, 八角墳) is also interpreted as reflecting Taoist cosmology, representing the `Hakko` (八紘, eight directions) including the cardinal and intercardinal points. This interest in Taoism was not unique to Tenmu, being evident in his mother Empress Saimei's reign and continuing after his death. Japanese Taoism, however, was not an independent religion but was deeply integrated with Shinto, making it challenging to precisely assess the extent of its influence.

4.7. Cultural Policies

Emperor Tenmu actively promoted and systematized traditional Japanese arts, literature, and indigenous cultural practices, distinguishing his reign from those that primarily adopted foreign influences.

4.7.1. Historical Compilation (Nihon Shoki, Kojiki)

Emperor Tenmu initiated monumental historical projects that laid the foundation for Japanese historiography. On March 17, 681, he issued an imperial edict commanding imperial princes and numerous ministers to compile "Imperial Chronicles and Ancient Matters" (`Teiki` and `Jōko Shōji`). This marked the beginning of the `Nihon Shoki` (日本書紀Nihon ShokiJapanese) ("Chronicles of Japan") compilation project.

Concurrently, he instructed Hieda no Are to memorize and recite the "Chronicles of Emperors" (`Teiō Hitsugi`) and "Old Narratives" (`Sendai Kyūji`), which contained imperial genealogies and ancient legends. These oral traditions were later transcribed by Ō no Yasumaro to become the `Kojiki` (古事記KojikiJapanese) ("Record of Ancient Matters"), completed in 712. Both `Nihon Shoki` and `Kojiki` were completed after Tenmu's death and are the oldest extant historical texts in Japan. While the exact intent behind commissioning two parallel historical works is debated, both served to legitimize imperial rule. `Nihon Shoki`, written in classical Chinese, is a lengthy work that often presents multiple versions of events, suggesting a collaborative compilation. In contrast, `Kojiki`, written in a more consistent style, is thought to reflect Tenmu's personal will to a greater extent.

4.7.2. Literature and Arts (Man'yōshū)

Emperor Tenmu had a deep appreciation for poetry and performing arts. His personal interest in `waka` (和歌, Japanese poetry) is evident in poems attributed to him in the `Man'yōshū` (万葉集Man'yōshūJapanese) ("Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves"). These include love poems exchanged with Princess Nukata at Gamo-no-no, playful verses with Fujiwara no Hikami-no-iratsume, and melancholic poems about the solitude of Yoshino.

- One famous poem attributed to him is:

Our Sovereign, a god,

: Has made his Imperial City

:Out of the stretch of swamps,

:Where chestnut horses sank

:To their bellies.

This poem, found in the Man'yōshū, describes the establishment of his capital at Asuka Kiyomihara, transforming a marshy area into a grand city.

- Another poem, exchanged with Princess Nukata at Gamo-no-no during a hunting trip with Emperor Tenji, reflects a complex relationship:

`Murasaki no nihoeru imo wo niku karaba / Hitotsuma yue ni a kōime yamo`

(If I hated my beloved, who shines like purple, / Would I still long for her, even though she is another's wife?)

- Two other poems express a somber mood during his retreat to Yoshino:

`Miyoshino no Mimiga no mine ni / Toki naku zo yuki wa furikeru / Hima naku zo ame wa furikeru / Sono yuki no toki naki ga goto / Sono ame no hima naki ga goto / Kumamo ochizu / Omoitsutsu zo koshi / Sono yamamichi wo`

(On the Mimiga Peak of fair Yoshino, / Snow falls ceaselessly, / Rain falls without pause. / Like the ceaseless snow, / Like the endless rain, / Without a moment's rest, / I came, thinking of you, / Along this mountain path.)

`Yoki hito no Yoshi to yoku mite yoshi to iishi / Yoshino yoku miyo yoki hito yoku mitsu`

(The good person, seeing Yoshino well and saying "good," / See Yoshino well, the good person saw it well.)

These poems are often interpreted as reflecting his somber mood during his retreat to Yoshino when Emperor Tenji was gravely ill.

Tenmu also actively patronized performing artists. In 675, he ordered the gathering of skilled singers, dancers, dwarves, and performers from `Kinai` and its surroundings to the court, rewarding them for their talents. In 685, he commanded that excellent songs and flute playing be passed down to future generations, and in 686, he rewarded actors and singers. He also enjoyed popular pastimes such as `mudan-goto` (riddles) and even hosted a `bakuchi` (gambling) tournament in 674.

4.7.3. Astronomy and Calendar

Emperor Tenmu had a keen interest and expertise in astronomy, as noted in the `Nihon Shoki`. In 675, he established Japan's first astronomical observatory, the `Senseidai` (占星台, Star-Gazing Platform). This initiative reflects his interest in divination and the influence of Taoist practices, which often incorporated astronomical observations. Advancements in calendar systems also occurred during his reign, contributing to more accurate timekeeping and agricultural planning.

4.8. Purges and Control

Emperor Tenmu's reign, while marked by significant reforms, also saw instances of political purges, punishments, and measures to maintain imperial authority and suppress dissent. These actions often targeted high-ranking imperial family members and ministers.

Punishments began in 675 with `Tōma no Hiromaro` and `Kunu no Maro` being forbidden from court attendance. This extended to high officials like `Prince Ōmi` (麻績王), who was exiled to `Inaba Province` in 675. In the same year, an individual committed suicide after uttering "seditious words" from a mountain east of the palace, likely criticizing the Emperor's policies. In 676, `Prince Yakaki`, the `Chikushi Dazai` (Governor-General of Kyushu), was exiled to `Tosa Province`, and in 677, `Kuidana Kura` was exiled to `Izu Ōshima` for criticizing the Emperor. While reasons for many punishments are unstated, the `Man'yōshū` includes sympathetic poems exchanged with Prince Ōmi, indicating public discontent. This suggests that the populace was not entirely unified in their praise of the Emperor. Even imperial family members involved in `kōshin seiji` faced dissatisfaction.

Emperor Tenmu also issued several threatening edicts. In 675, he commanded all ministers, officials, and people to "commit no evil." In 677, he admonished the `Yamato no Aya` clan for past political conspiracies, forgiving them but warning against future transgressions. In 679, he reprimanded imperial princes and ministers for being negligent and overlooking "evil persons."

These purges and threats were concentrated between 675 and 677, coinciding with Tenmu's reforms to reclaim private lands and restructure `fuko`. Historians suggest these actions were a response to resistance from those disadvantaged by his policies. Despite these measures, Tenmu generally avoided imposing death penalties on high officials, except for Prince Ōtsu, who was executed for treason shortly after Tenmu's death. He also frequently issued general amnesties, such as in 679, which likely pardoned many who had been exiled.

5. Family

Emperor Tenmu had numerous wives, consorts, and children, many of whom played significant roles in subsequent Japanese history. His marriages, particularly to the daughters of Emperor Tenji, were strategic alliances to consolidate imperial power and lineage.

- Empress Kōgō (皇后Japanese): Princess Uno-no-sarara (鸕野讃良皇女Uno-no-sarara no HimemikoJapanese), later Empress Jitō (645-703), daughter of Emperor Tenji.

- Second Son: Prince Kusakabe (草壁皇子Kusakabe no ŌjiJapanese, 662-689). Father of Emperor Monmu and Empress Genshō.

- Consort Hi (妃Japanese): Princess Ōta (大田皇女Ōta no HimemikoJapanese), daughter of Emperor Tenji, elder sister of Empress Jitō.

- Second Daughter: Princess Ōku (大伯皇女Ōku no HimemikoJapanese, 661-701). Served as `Saiō` at Ise Grand Shrine (673-686).

- Third Son: Prince Ōtsu (大津皇子Ōtsu no ŌjiJapanese, 663-686).

- Consort Hi (妃Japanese): Princess Ōe (大江皇女Ōe no HimemikoJapanese), daughter of Emperor Tenji, half-sister of Empress Jitō.

- Seventh Son: Prince Naga (長皇子Naga no ŌjiJapanese, died 715). Ancestor of the `Fumuro` clan.

- Ninth Son: Prince Yuge (弓削皇子Yuge no ŌjiJapanese, died 699).

- Consort Hi (妃Japanese): Princess Niitabe (新田部皇女Niitabe no HimemikoJapanese), daughter of Emperor Tenji, half-sister of Empress Jitō.

- Sixth Son: Prince Toneri (舎人親王Toneri ShinnōJapanese, 676-735). Father of Emperor Junnin. Ancestor of the `Kiyohara` clan.

- Madame Bunin (夫人Japanese): Fujiwara no Hikami-no-iratsume (藤原氷上娘Fujiwara no Hikami-no-iratsumeJapanese, died 682), daughter of Fujiwara no Kamatari.

- Daughter: Princess Tajima (但馬皇女Tajima no HimemikoJapanese, died 708). Married to Prince Takechi.

- Madame Bunin (夫人Japanese): Fujiwara no Ioe-no-iratsume (藤原五百重娘Fujiwara no Ioe-no-iratsumeJapanese), daughter of Fujiwara no Kamatari, younger sister of Hikami-no-iratsume. Later married Fujiwara no Fuhito.

- Tenth Son: Prince Niitabe (新田部親王Niitabe ShinnōJapanese, died 735). Ancestor of the `Hikami` and `Mihara` clans.

- Madame Bunin (夫人Japanese): Soga no Ōnu-no-iratsume (蘇我大蕤娘Soga no Ōnu-no-iratsumeJapanese), daughter of Soga no Akae (蘇我赤兄Japanese).

- Fifth Son: Prince Hozumi (穂積皇子Hozumi no ŌjiJapanese, died 715).

- Daughter: Princess Ki (紀皇女Ki no HimemikoJapanese).

- Daughter: Princess Takata (田形皇女Takata no HimemikoJapanese, 674-728). Served as `Saiō` at Ise Grand Shrine (706-707). Later married Prince Mutobe.

- Beauty Hin (嬪Japanese): Princess Nukata (額田王Nukata no ŌkimiJapanese), daughter of Prince Kagami.

- First Daughter: Princess Tōchi (十市皇女Tōchi no HimemikoJapanese, c. 653-678). Married to Emperor Kōbun. Her 12th generation descendant, Emperor Ichijō, later brought Tenmu's matrilineal bloodline back into the imperial succession.

- Beauty Hin (嬪Japanese): Munakata no Amako-no-iratsume (胸形尼子娘Munakata no Amako-no-iratsumeJapanese), daughter of Munakata-no-Kimi Tokuzen (宗形徳善Japanese).

- First Son: Prince Takechi (高市皇子Takechi no ŌjiJapanese, 654-696). Father of Prince Nagaya and Prince Suzuka. Ancestor of the `Takashina` clan.

- Beauty Hin (嬪Japanese): Shishihito no Kajihime-no-iratsume (宍人梶媛娘Shishihito no Kajihime-no-iratsumeJapanese), daughter of Shishihito-no-Omi Ōmaro (宍人大麻呂Japanese).

- Fourth Son: Prince Osakabe (刑部親王Osakabe ShinnōJapanese, died 705). Ancestor of the `Tatsuta`, `Kiyotaki`, and `Mitaka` clans.

- Son: Prince Shiki (磯城皇子Shiki no ŌjiJapanese). Ancestor of the `Misono`, `Kasahara`, and `Kiyoharu` clans.

- Daughter: Princess Hatsusebe (泊瀬部皇女Hatsusebe no HimemikoJapanese, died 741). Married to Prince Kawashima (son of Emperor Tenji).

- Daughter: Princess Taki (託基皇女Taki no HimemikoJapanese, died 751). Served as `Saiō` at Ise Grand Shrine (698-before 701). Later married Prince Shiki (son of Emperor Tenji).

Emperor Tenmu's direct imperial lineage ended with Empress Kōken (later Empress Shōtoku), his great-great-granddaughter. The imperial succession then passed to Emperor Kōnin, a grandson of Emperor Tenji. However, Tenmu's bloodline was later reintroduced into the imperial family through the matrilineal descent of Emperor Ichijō, who ascended the throne in 986 and was a 12th-generation descendant of Princess Tōchi. Many of Tenmu's children also founded prominent aristocratic clans, such as the `Kiyohara` clan (descended from Prince Toneri) and the `Takashina` clan (descended from Prince Takechi), ensuring the long-term prosperity of his descendants.

6. Personality and Legacy

6.1. Character and Interests

Emperor Tenmu was known for his strong interest in religion and supernatural powers, possessing deep faith in both Shinto deities and Buddhist teachings. The `Nihon Shoki` describes him as skilled in `Tenmon Tonkō` (astronomy and divination). During the Jinshin War, he reportedly performed divinations to predict the outcome and prayed to the gods to stop thunderstorms, which were seen as evidence of his prophetic abilities and divine favor. These abilities contributed to his charismatic reputation as a ruler revered like a god. His reign also saw a strong emphasis on religious rituals and the use of divination to achieve his political goals.

Tenmu's personal tastes extended to traditional Japanese arts and popular entertainments. While there are no records of him composing Chinese poetry, his `waka` poetry is well-documented in the `Man'yōshū`. He also enjoyed common pastimes, such as `mudan-goto` (riddles) and even hosted a `bakuchi` (gambling) tournament at the `Daian-den` in 674. His patronage of various performing artists, including singers, dancers, dwarves, and actors, also suggests a preference for popular forms of entertainment. These aspects of his personality may have helped him connect with and gain the support of the common people and regional clans.

Physical descriptions from the `Afukiyama Ryōki`, a document from 1235 detailing the excavation of his tomb, suggest that Emperor Tenmu was of imposing stature. His skull was slightly larger than average and reddish-black, his shin bones measured 19 in (48 cm), and his elbows 17 in (42 cm). From these measurements, his height is estimated to have been around 69 in (175 cm), which was considered tall for his era. The diary of Fujiwara no Sadaie, `Meigetsuki`, also noted that white hair remained on his skull, even centuries after his death.

6.2. Historical Evaluation

Emperor Tenmu's reign is widely regarded as a transformative period that laid the fundamental groundwork for the centralized imperial state in Japan. His victory in the Jinshin War solidified his position as a powerful and charismatic ruler, enabling him to implement far-reaching reforms. He is highly praised for his contributions to state-building, including the establishment of the `Ritsuryō` system, the reorganization of the `kabane` system, and the centralization of power under the Emperor. His initiatives in historical compilation (`Nihon Shoki`, `Kojiki`) were crucial in legitimizing the imperial lineage and shaping a national identity.

However, his rule also exhibited autocratic tendencies. He concentrated power directly in his hands, bypassing the traditional role of ministers, and relied heavily on members of the imperial family (`kōshin seiji`). His reign saw instances of political purges and intimidating edicts against those perceived as disloyal or resistant to his reforms. While these measures were often aimed at consolidating imperial authority and ensuring stability, they reflect a ruler who did not hesitate to suppress dissent.

The `Nihon Shoki`, a primary source for his life, was compiled under the direction of his son, Prince Toneri, and completed during the reigns of his wife and children. This raises questions about its impartiality and accuracy, as it naturally portrays Tenmu in a highly favorable light, emphasizing his innovations and divine mandate. Despite this potential bias, it is clear that Tenmu significantly strengthened the Emperor's power, reducing the influence of powerful clans like the Ōtomo clan and Soga clan. His legacy is that of a strong, visionary, and sometimes ruthless leader who fundamentally reshaped Japan's political, social, and cultural landscape, setting the stage for the classical `Ritsuryō` state.

7. Death and Tomb

Emperor Tenmu fell ill on May 24, 686. Despite prayers and Buddhist rituals performed for his recovery, his condition did not improve. On July 15, he entrusted political affairs to his Empress and Crown Prince. On July 20, he proclaimed the new era name `Shuchō` (朱鳥), meaning "Vermilion Bird," a Taoist concept associated with vitality and rejuvenation, hoping for his recovery. The palace was also formally named `Asuka Kiyomihara Palace` at this time, with the name `Kiyomihara` (浄御原) also reflecting a wish for purification and healing from illness. However, these measures proved ineffective. Emperor Tenmu died on October 1, 686.

A month after his death, on October 2, Prince Ōtsu, his talented son, was arrested on suspicion of rebellion and executed the following day. Emperor Tenmu's funeral rites (`bin`, 殯) were prolonged, with the Crown Prince leading numerous ceremonies. He was finally interred on November 21, 688, at `Ōuchi-ryō` (大内陵). His wife, Empress Jitō, who had served as his regent during his illness, officially ascended the throne as Empress Jitō after the death of their son, Prince Kusakabe, on March 13, 689.

Emperor Tenmu's imperial tomb, formally named `Hinokuma no Ōuchi no Misasagi` (檜隈大内陵Hinokuma no Ōuchi no MisasagiJapanese), is located in Noguchi, Asuka-mura, Takaichi District, Nara Prefecture. It is a joint burial mound with Empress Jitō, taking the form of an `age-kaza-hōfun` (上円下方墳), a square base with a circular mound on top (or an octagonal mound, `hakkaku-fun`). Unusually for ancient imperial tombs, its identification is considered accurate.

The tomb was notably plundered in 1235 (Bunryaku 2nd year), with most of the grave goods stolen. The coffin was also disturbed, but the Emperor's remains were left largely intact, with white hair reportedly still clinging to his skull. Empress Jitō's cremated remains, originally in a silver urn, were discarded nearby after the urn was stolen. The details of this robbery were recorded in Fujiwara no Sadaie's diary, `Meigetsuki`, and in the `Afukiyama Ryōki`, which also described the interior of the stone chamber.

Separately, the `Unebi Ryōbo Sankōchi` (畝傍陵墓参考地) in Gojōno-chō, Kashihara City, Nara Prefecture, is also considered a potential burial site for Emperor Tenmu and Empress Jitō. This site is known as the `Maruyama Kofun` (五条野丸山古墳). In addition to his physical tomb, Emperor Tenmu's spirit is enshrined at the `Kōrei-den` (皇霊殿), one of the Three Palace Sanctuaries within the Tokyo Imperial Palace, alongside other successive emperors and imperial family members.