1. Early life and background

David Millar was born on January 4, 1977, in Mtarfa, Malta. His parents, Gordon and Avril Millar, were both Scots. His father served as a pilot in the Royal Air Force, and Millar's birth occurred during his father's three-year tour of duty in Malta. His mother worked as a teacher. Millar has a sister, Frances (Fran) Millar, who also pursued a career in cycling and currently serves as the chief executive officer of Team Ineos.

After their time in Malta, the family returned to the United Kingdom, first residing at RAF Kinloss in Scotland before moving to Aylesbury, approximately 37 mile (60 km) north-west of London. When Millar was 11, his parents divorced, and his father relocated to Hong Kong to join the airline Cathay Pacific. Millar moved to Hong Kong to live with his father at the age of 13 and considers Hong Kong his home. During his time there, he participated in BMX bike races, achieving notable success. In 1992, he acquired a road bicycle and began racing early in the mornings before the roads became congested with traffic.

Millar attended King George V School in Hong Kong, where he initially selected mathematics, economics, and geography for his A-level examinations. However, at his father's suggestion, he later switched to art, graphics, and sports studies. After completing his A-levels, he moved back to England to live with his mother in Maidenhead and enrolled in an arts college. He began cycling with a club in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, with his mother's encouragement to help him make new friends and find an activity. At 18, just a week before he was scheduled to start at the arts college, Millar traveled to France to race. He joined a cycling club in St-Quentin, located in the Picardy region, where he achieved eight victories. His talent attracted contract offers from five professional teams, but he ultimately signed with Cofidis, a team based in the area and led by Cyrille Guimard, who was renowned for his ability to identify young talent.

2. Professional career

David Millar's professional cycling career spanned from 1997 to 2014, marked by significant achievements, a major doping scandal, and a subsequent transformation into an anti-doping advocate.

2.1. Debut and early career (1997-2003)

Millar began his professional career in 1997 with the Cofidis team. In his debut season, he won the prologue of the Tour de l'Avenir and the best young rider competition in the Mi-Août Breton. His background in 10-mile time trials in Britain proved advantageous, leading to his victory in the first stage of the 2000 Tour de France, a 9.9 mile (16 km) time trial at Futuroscope. This win earned him the yellow jersey as the leader of the general classification, which he held for three days.

In 2001, Millar aimed to repeat his prologue success at Dunkirk but crashed after a puncture on a bend. Despite this setback, he secured overall victory at the Danmark Rundt and won two stages (Stage 1, an individual time trial, and Stage 6) at the 2001 Vuelta a España. He also earned a silver medal in the World Time Trial Championship, finishing second to Jan Ullrich. Representing Malta, Millar won a gold medal in the time trial at the 2001 Games of the Small States of Europe in San Marino. He was selected for the Scotland team for the 2002 Commonwealth Games but withdrew to compete for Cofidis.

Millar won stage 13 of the 2002 Tour de France. Later that year, during stage 15 of the 2002 Vuelta a España, which included the ascent of the Alto de l'Angliru in heavy rain, Millar experienced significant difficulties. Team cars stalled on the steepest sections, blocking riders, and some cyclists were forced to ride with flat tires due to mechanics being unable to reach them. Millar himself crashed three times. In protest of the chaotic conditions, he abandoned the race by handing in his race number a meter from the finish line. Although he later regretted his temper and apologized to his team, the judges ruled he had not finished the stage, and he was not reinstated.

In the 2003 Tour de France, Millar's attempt to win the prologue in central Paris ended in disappointment when his chain dropped 500 meters from the finish line. He lost by a mere 0.14 seconds to Brad McGee. Millar had ridden a bike without a front derailleur to save weight, a decision he blamed on his directeur sportif, Alain Bondue. Bondue was subsequently demoted to logistics manager. Millar later won stage 19, an individual time trial, of the 2003 Tour de France. He also won stage 17 of the 2003 Vuelta a España. In the World Time Trial Championship, Millar initially claimed victory, but this title was later revoked due to a doping admission.

2.2. Doping incident and suspension (2004-2005)

David Millar's career took a dramatic turn on June 23, 2004, when he was detained by three plainclothes policemen from the Paris drug squad in Bidart, near Biarritz. The raid on his home, which lasted two and a half hours, uncovered empty vials of Eprex, a brand of the blood-boosting drug erythropoietin (EPO), and two used syringes. Millar initially claimed these were gifts from the Tour of Spain and that he had kept them as souvenirs.

The investigation was linked to the earlier arrest of Bogdan Madejak, a Cofidis soigneur, and the subsequent questioning of another team rider, Philippe Gaumont. Gaumont alleged that he had provided Millar with drugs and syringes the day before the 2003 Tour de France concluded, a race in which Millar won the final time trial. Millar initially denied Gaumont's claims, dismissing them as "absolute crap" and defending team doctor Menuet. However, after four months of police phone taps, Millar confessed to the authorities on June 24, 2004.

Millar admitted to using EPO in 2001 and 2003, attributing his actions to intense stress, particularly the pressure of losing the 2003 Tour prologue and being defeated by Jan Ullrich in the 2001 world time trial championship. Under cycling regulations, a confession is treated as a positive drug test. As a result, British Cycling suspended him for two years in August 2004. He was stripped of his 2003 world time trial championship title, which was subsequently awarded to Michael Rogers. Millar was also fined 1.25 K EUR and disqualified from the 2003 Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré and the 2001 Vuelta a España. Cofidis immediately fired Millar and temporarily withdrew from racing to conduct an internal investigation, which led to the dismissal of several riders and assistants, including director Alain Bondue and doctor Menuet.

Millar appealed to the Court of Arbitration for Sport to reduce his ban, but the appeal was unsuccessful, though his suspension was backdated to the date of his confession, June 24, 2004. In 2006, a French court in Nanterre prosecuted Millar alongside nine other defendants, mostly from Cofidis. However, the court dismissed the charges against Millar, stating it was unclear whether he had taken drugs within France. Millar later revealed that the doctor he had consulted resided in Spain. In his statement to the judge, Millar described succumbing to the immense pressure of racing, the high expectations from British fans, and his struggle to form close friendships. He noted that winning the Tour de France prologue, his "dream," paradoxically worsened his isolation, leaving him alone in his apartment with only a television for company after the excitement subsided.

Millar estimated that doping had gained him 25 seconds in the 2003 world time trial championship. The consequences of his doping admission were severe: he lost his job, his income, and his house. For much of a year, Millar struggled with alcohol abuse. He later stated that he managed to get by with the support of his family and friends.

2.3. Return and comeback (2006-2007)

After serving his two-year suspension, David Millar made his return to professional cycling. He moved to Hayfield, on the edge of the Peak District in northern England, to be closer to the Manchester Velodrome, the headquarters of British cycling. He signed with the Spanish team Saunier Duval-Prodir in 2006, after being contacted by its manager, Mauro Gianetti, nine months into his ban.

Millar's suspension concluded just a week before the 2006 Tour de France, and he participated in the race. He finished 17th in the prologue and 11th in the penultimate time-trial stage, ultimately placing 59th overall. In the 2006 Vuelta a España, Millar secured a significant victory by winning stage 14, an individual time trial held around the city of Cuenca, where he notably defeated Fabian Cancellara, who would become the world time trial champion that year. On October 3, he further demonstrated his versatility by winning the British 4,000m individual pursuit championship in 4 minutes and 22.32 seconds at Manchester.

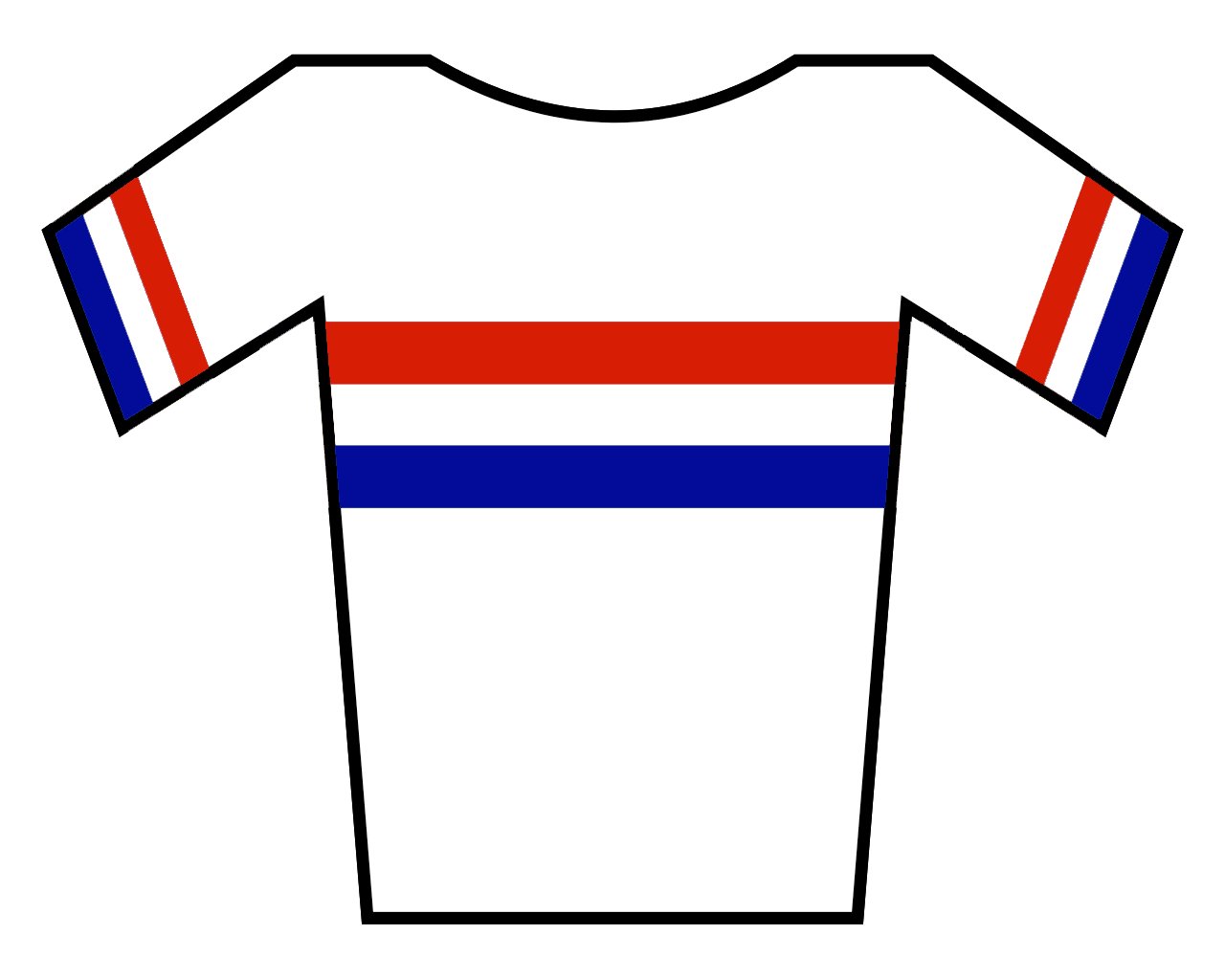

In 2007, Millar departed Saunier Duval-Prodir to join an American team, Slipstream, which later became Garmin Slipstream. This move was significant as the team, led by former rider Jonathan Vaughters, emphasized a strong stance against doping. During the 2007 season, Millar achieved a remarkable double victory by winning both the British national road race and time trial championships. He also finished second overall in the Eneco Tour, just 11 seconds behind José Iván Gutiérrez, and won the prologue of Paris-Nice.

2.4. Career with Garmin-Sharp (2008-2014)

In 2008, Slipstream rebranded as Garmin Slipstream, and David Millar became a part-owner of the team, actively promoting its anti-doping principles. He played a key role in the team's victory in the opening team time trial of the 2008 Giro d'Italia. However, during stage five of the same Giro, while part of a five-man winning breakaway, his chain broke in the final kilometer, causing him to throw his bike to the roadside. In the 2008 Tour de France, Millar finished third in the stage four time trial. His best overall result of the season was a second-place finish in the 2008 Tour of California.

Millar competed in the 2009 Giro d'Italia and then the 2009 Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré, where he finished ninth overall. He also participated in both the 2009 Tour de France and the 2009 Vuelta a España. His most notable performance was winning the stage 20 time trial at the Vuelta, marking his first victory in two years and his fifth stage win at the Vuelta. He also received the combativity award on stage 6 of the 2009 Tour de France.

The 2010 season saw Millar continue his strong time-trial form, with stage wins at the Critérium International and the Three Days of De Panne. His victory at De Panne also marked his first multi-stage race win since the 2001 Circuit de la Sarthe. He achieved high placings in several major time trials earlier in the season, including a third-place finish in the prologue of the 2010 Tour de France and second in stage three of the 2010 Critérium du Dauphiné. Despite an injury sustained during the Tour de France, he completed all three Grand Tours. Millar then matched his best "clean" placing at the Men's World Time-Trial Championships, finishing second behind Fabian Cancellara. Shortly thereafter, at the 2010 Commonwealth Games, he won a gold medal in the time trial and a bronze in the road race.

In 2011, Millar suffered from illness early in the season, causing him to miss many of the classics. His best performance was a third-place finish in the overall classification of the Circuit de la Sarthe. He recovered in time for the 2011 Giro d'Italia, finishing second on stage 3 to claim the pink jersey as the leader of the general classification. Millar's leadership role during the Giro was notably overshadowed by the tragic death of Wouter Weylandt on the same day; Millar played a crucial part in organizing the tributes to Weylandt during the subsequent neutralized stage. He later won the stage 21 individual time trial of the Giro, becoming only the third British rider-after Robert Millar and Mark Cavendish-to achieve stage victories in all three Grand Tours during his career. In June, he published his autobiography, Racing Through the Dark, which was widely praised as a significant account of sporting experience. Millar also served as the team captain for the Great Britain team that helped Mark Cavendish win the 2011 UCI World Championships road race.

On March 23, 2012, Millar fractured his collarbone in a crash during the 2012 E3 Harelbeke one-day race in Belgium. He returned to competition at the Tour of Bavaria and the Critérium du Dauphiné. Despite his injuries, Millar was selected to ride his 11th Tour de France. He won stage 12 by breaking away with four other riders, arriving 3.1 mile (5 km) from the finish line in Annonay-Davézieux with a significant lead over the main peloton. He secured the win after a tactical battle with Jean-Christophe Péraud. This victory made him the fourth British rider to win a stage in a Tour de France, coinciding with Bradley Wiggins becoming the second British rider to win the overall event. Millar was also selected for the British Road Race Team for the London Olympics. He reprised his role as team captain from the 2011 World Championships, aiming to guide Mark Cavendish to victory. However, Millar and his GB teammates Bradley Wiggins, Ian Stannard, and Chris Froome were largely left to set the pace for the majority of the race with little assistance from other nations. They were ultimately unable to catch a thirty-man breakaway that had formed on the final climb of the Box Hill circuit, resulting in Cavendish finishing 40 seconds behind the winner, Alexander Vinokourov.

In 2013, Millar finished third in the National Road Race Championships. Millar was not selected for the 2014 Tour de France team, a decision that left him "devastated and shocked." He retired from professional cycling after the 2014 season, with his final competitive start being the Bec CC Hill Climb in October. The final year of Millar's career was documented in the film Time Trial by filmmaker Finlay Pretsell. The film, intended as an insight into professional cycling, evolved to explore themes of aging and retirement as it chronicled Millar's increasing realization that he could no longer perform at his previous levels. Time Trial was released in UK cinemas on June 29, 2018.

2.5. Retirement

David Millar officially retired from professional cycling at the end of the 2014 season. His final competitive appearance was at the Bec CC Hill Climb in October of that year.

The documentary film Time Trial, directed by Finlay Pretsell, captured the events of Millar's last year as a professional cyclist. Initially conceived to offer an inside look into the world of professional cycling, the film ultimately delved into deeper themes of aging and the transition from a demanding career, as it chronicled Millar's growing awareness of his inability to maintain his previous performance levels. The film was released in the UK on June 29, 2018.

3. Major results and achievements

David Millar achieved numerous significant results throughout his professional cycling career, including stage wins in all three Grand Tours and multiple national and international championship medals.

3.1. Grand Tour stage wins

Millar is one of only three British riders to have won stages in all three Grand Tours:

- Tour de France

- 2000: Stage 1 (Individual Time Trial)

- 2002: Stage 13

- 2003: Stage 19 (Individual Time Trial) - *Later voided due to doping admission*

- 2011: Stage 2 (Team Time Trial)

- 2012: Stage 12

- Giro d'Italia

- 2008: Stage 1 (Team Time Trial)

- 2011: Stage 21 (Individual Time Trial)

- Vuelta a España

- 2001: Stage 1 (Individual Time Trial), Stage 6

- 2003: Stage 17 - *Later voided due to doping admission*

- 2006: Stage 14 (Individual Time Trial)

- 2009: Stage 20 (Individual Time Trial)

3.2. Championships and awards

Millar's notable championship victories and awards include:

- Games of the Small States of Europe

- 2001: Gold medal, Time trial

- UCI Road World Championships

- 2001: Silver medal, Time trial

- 2003: Gold medal, Time trial - *Disqualified*

- 2010: Silver medal, Time trial

- Commonwealth Games

- 2010: Gold medal, Time trial

- 2010: Bronze medal, Road race

- British National Road Race Championships

- 2007: Winner

- British National Time Trial Championships

- 2007: Winner

- British National Track Championships

- 2006: Winner, Individual pursuit (4000m)

- Overall Stage Race Victories

- 2001: Circuit de la Sarthe

- 2001: Danmark Rundt

- 2003: Tour de Picardie

- 2010: Three Days of De Panne

- 2010: Chrono des Nations

The following tables summarize David Millar's Grand Tour general classification results and major championship results throughout his career.

Grand Tour general classification results timeline Grand Tour 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 alt=Pink jersey Giro d'Italia

94 DNF DNF 99 DNF alt=Yellow jersey Tour de France

62 DNF 68 55 56 68 67 82 157 76 106 113 alt=golden jersey Vuelta a España

41 DNF 103 64 80 108 144 Legend - Did not compete DNF Did not finish Major championship results timeline Event 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 link=Gold medal Olympic Games

Time trial Not held 16 Not held - Not held - Not held - Not held Road race - - - 108 link=Rainbow jersey World Championships

Time trial 20 - - - 2 6 1- - 15 18 9 - 2 7 - - - Road race - - - - DNF DNF 86 - - 35 54 DNF DNF DNF 114 - - DNF link=Gold medal Commonwealth Games

Time trial NH - Not held - Not held - Not held 1 Not held 8 Road race - - - 3 11 National Championships

Time trial - 2 2 - - - - - - - 1 3 - - - - - - Road race - - - 3 - - - - - - 1 25 - - - - 3 DNF

4. Anti-doping advocacy and sports ethics

Following his return to professional cycling after his two-year ban for doping, David Millar became a vocal and active campaigner for anti-doping efforts and clean sport. This stance eventually led journalist Alasdair Fotheringham to describe him as an 'elder statesman' of cycling.

Millar's commitment to clean sport was a key factor in his decision to join the Garmin Slipstream team in 2007, a team explicitly founded on anti-doping principles by former rider Jonathan Vaughters. He even became a part-owner of the team in 2008, further solidifying his dedication to fostering an ethical environment in cycling. His autobiography, Racing Through the Dark, published in 2011, provided a candid and widely acclaimed first-person account of his doping experience and subsequent redemption, contributing significantly to the discourse on sports integrity.

Millar played a crucial role as team captain for the Great Britain squad that helped Mark Cavendish win the 2011 UCI World Championships road race. This role was seen as a testament to his transformation and his influence as a proponent of clean competition. He continued his advocacy by representing the professional cyclists' body, Cyclistes Professionnels Associes (CPA), on the UCI's working group. This group was tasked with establishing an Extreme Weather Protocol to provide clear guidelines for race procedures during severe weather conditions, a protocol first implemented at the 2016 Paris-Nice.

In 2018, Millar took a significant step by challenging incumbent CPA president Gianni Bugno for the leadership of the organization. His campaign manifesto advocated for democratic reforms to the union's voting system, a financial audit of its finances, and improved communication with riders. This marked the first contested election in the CPA's history. Despite his efforts to empower the peloton and bring greater transparency, Millar was defeated by Bugno, receiving 96 votes to Bugno's 379.

5. Personal life

David Millar is married to Nicole. They have three children: their first son, Archibald Millar, was born on September 9, 2011; their second son, Harvey Millar, was born on May 2, 2013; and their daughter, Maxine Millar, was born on December 31, 2015.

In 2013, while consulting for the production of the film The Program, Millar sustained an unusual injury when he hit his head on a low-hanging beam in a hotel. This accident resulted in him losing his sense of smell.

Millar's sister, Fran Millar, was appointed CEO of the cycling team Team Ineos in June 2019. David Millar is not related to Robert Millar, a fellow Scottish road cyclist whose main successes occurred in the mid-1980s.

6. Assessment and impact

David Millar's career is notable not only for his significant athletic achievements but also for his profound transformation following a doping scandal, which left a lasting impact on the sport of cycling.

6.1. Positive contributions

Millar's return to professional cycling after his ban demonstrated remarkable resilience and a commitment to redemption. His subsequent and unwavering dedication to anti-doping advocacy has been widely recognized as a major positive contribution to the sport. Through his candid autobiography, Racing Through the Dark, and his active participation in initiatives like the UCI's Extreme Weather Protocol working group, Millar has provided invaluable insights into the pressures of professional cycling and the importance of integrity. He became a trusted voice for clean sport, influencing younger generations of riders and contributing to a more ethical environment within the peloton. His role as a team captain, notably in helping Mark Cavendish win the 2011 World Championships, further cemented his reputation as a leader dedicated to the collective success and ethical standards of his team.

6.2. Criticism and controversy

The primary source of criticism and controversy surrounding David Millar's career stems from his admission of using erythropoietin (EPO) in 2001 and 2003. This confession led to his disqualification from the 2003 World Time Trial Championship and a two-year ban from the sport. His initial denials of doping allegations, followed by his eventual confession, highlighted the pervasive issue of doping in cycling during that era. The personal consequences of his actions, including the loss of his job, income, and home, and a period of alcohol abuse, underscored the severe repercussions of such breaches of sports ethics. While his subsequent advocacy for clean sport has largely redeemed his public image, the doping incident remains a significant and controversial chapter in his career, serving as a stark reminder of the sport's past struggles with performance-enhancing drugs.

7. Post-racing career

Since retiring from professional cycling in 2014, David Millar has remained actively involved in the sport through various roles. In March 2015, he revealed he was coaching his former teammate Ryder Hesjedal. He has also taken on a mentoring role with the Great Britain under-23 cycling squad, guiding the next generation of riders.

Millar works as a cycling journalist and pundit, sharing his insights and analysis of races. Since 2016, he has served as a co-commentator for ITV's coverage of major cycling events, including the Tour de France and Vuelta a España. He also co-hosts "Never Strays Far," a cycling-focused podcast, with fellow ITV commentator Ned Boulting and former professional cyclist Peter Kennaugh.

In 2015, Millar launched his 'Chpt3' brand, collaborating with various partners to produce a range of cycling-related products, including bikes and clothing. His final year in professional cycling was documented in the film Time Trial, which offered an intimate look at his transition from competitive racing.