1. Overview

Cimon (Κίμων Μιλτιάδου ΛακιάδηςKimōn Miltiadou LakiadēsGreek, Ancient; c. 510 - 450 BC) was an influential Athenian general and statesman in the mid-5th century BC. He was the son of Miltiades, the victor of the Battle of Marathon. Cimon played a pivotal role in the rise of Athens as a dominant naval power following the failure of Xerxes I's Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480-479 BC. He distinguished himself through his military prowess, becoming a renowned military hero and being elevated to the rank of admiral after fighting bravely in the Battle of Salamis.

Cimon's most significant military achievement was the decisive destruction of the Persian fleet and army at the Battle of the Eurymedon in 466 BC. He was a leading figure in the formation of the Delian League against Persia in 478 BC and commanded most of its operations until 463 BC, marking the transformation of the League into the Athenian Empire. Politically, Cimon championed the aristocratic faction in Athens, opposing the democratic reforms advocated by Ephialtes and Pericles that aimed to shift power from the traditional elite to the populace. He was known for his pro-Spartan foreign policy, acting as Sparta's representative in Athens and advocating for cooperation between the two states. However, his unsuccessful expedition to support Sparta during the Third Messenian War in 462 BC led to his ostracism from Athens in 461 BC. Despite his exile, he was recalled in 451 BC to mediate a five-year truce between Sparta and Athens. Cimon also contributed significantly to the reconstruction and beautification of Athens after the Persian Wars, funding numerous public works. He died in 450 BC during a military expedition to Cyprus.

2. Life

Cimon's life was marked by his noble birth and early struggles with inherited debt, his strategic marriages, and a distinguished military career that saw him rise to prominence in the Delian League. His political leanings and pro-Spartan foreign policy ultimately led to his temporary exile, from which he returned to contribute to Athens' reconstruction before his final military campaign.

2.1. Early Life and Family Background

Cimon was born into Athenian nobility around 510 BC, a member of the prominent Philaidae clan from the deme of Laciadae. His grandfather was Cimon Coalemos, a celebrated figure who achieved three victories in the Ancient Olympic Games with his four-horse chariot before being assassinated by the sons of Peisistratus. Cimon's father was the renowned Athenian general Miltiades, who famously defeated the Achaemenid Persian forces at the Battle of Marathon. His mother was Hegesipyle, the daughter of Olorus, a Thracian king, and a relative of the esteemed historian Thucydides.

In his youth, Cimon inherited a substantial debt of 50 talents from his father, who had been fined by the Athenian state on charges of treason after the failed Siege of Paros. Miltiades was unable to pay this sum and subsequently died in prison in 489 BC. According to the historian Diodorus, Cimon inherited not only this debt but also a portion of his father's unserved prison sentence, which he had to fulfill to secure his father's body for burial. As the head of his household, Cimon also became responsible for his sister or half-sister, Elpinice.

2.2. Marriage and Personal Life

According to Plutarch, the wealthy Athenian Callias proposed to pay Cimon's inherited debts in exchange for Elpinice's hand in marriage. Although Cimon initially refused, Elpinice accepted the proposal, reportedly to prevent her brother from suffering the same fate as their father, who had died in prison. There are accounts, possibly stemming from political slander, that Cimon had been involved with Elpinice prior to her marriage to Callias, and she herself had a reputation for sexual promiscuity.

Cimon later married Isodice, the granddaughter of Megacles and a member of the powerful Alcmaeonidae family. This marriage, along with Elpinice's to Callias, represented a significant alliance among leading aristocratic families in Athens, potentially forming a noble coalition to counter the rising influence of Themistocles after his successes in the Persian Wars. Cimon and Isodice had three sons: twin boys named Lacedaimonius and Eleus, and a third son named Thessalus. The names of his sons, Lacedaemonius (meaning "Lacedaemonian" or "Spartan"), Eleus (meaning "Elean" or "from Elis"), and Thessalus (meaning "Thessalian"), reflected Cimon's pro-Spartan and "foreign-influenced" leanings, a characteristic that later drew criticism from political opponents like Pericles.

In his youth, Cimon had a reputation for being dissolute, a heavy drinker, and possessing a blunt and unrefined manner. It was often remarked that in these latter characteristics, he resembled a Spartan more than an Athenian.

2.3. Military Career

Cimon's military career began to flourish during the Second Persian invasion of Greece. He distinguished himself with his bravery in the naval Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. Following this, he was part of an Athenian embassy sent to Sparta in 479 BC.

Between 478 BC and 476 BC, Cimon was elected as one of the ten strategoi and played a crucial role in the formation of the Delian League, a confederacy of Greek maritime cities that sought to prevent future Persian control. He became the League's principal commander and led most of its operations until 463 BC. During this period, Cimon, alongside Aristides, successfully expelled the Spartan general Pausanias from Byzantium, whose tyrannical behavior had alienated the Greek allies.

Cimon continued his campaigns against Persia, capturing Eion on the Strymon River from the Persian general Boges in 476 BC. Following the fall of Eion, many other coastal cities in the region surrendered to him, with the notable exception of Doriscus. He also conquered the island of Scyros, driving out the pirates who had established a base there. Upon his return to Athens, Cimon brought back the supposed "bones" of the mythological hero Theseus, an act celebrated by the erection of three Herma statues around the city.

Around 466 BC, Cimon took the war against Persia into Asia Minor, where he achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of the Eurymedon river in Pamphylia. His combined land and sea forces captured the Persian camp and either destroyed or captured the entire Persian fleet of 200 triremes, which were primarily manned by Phoenicians. Following this victory, Cimon established an Athenian colony nearby called Amphipolis, settling it with 10,000 settlers. Many new allies, such as the trading city of Phaselis on the Lycian-Pamphylian border, were subsequently recruited into the Delian League. Some historians suggest that Cimon may have negotiated a peace treaty between the League and the Persians after his victory at Eurymedon, which could explain why the later Peace of Callias in 450 BC is sometimes referred to as the Peace of Cimon, implying a renewal of an earlier agreement. Plutarch praised Cimon's military capabilities, stating that "In all the qualities that war demands he was fully the equal of Themistocles and his own father Miltiades."

After his successes in Asia Minor, Cimon moved to the Thracian Chersonesus, where he subdued local tribes and suppressed the revolt of the Thasians between 465 BC and 463 BC. The island of Thasos had rebelled from the Delian League due to a trade rivalry over the Thracian hinterland and, specifically, the ownership of a gold mine. Cimon's Athenian fleet defeated the Thasian fleet, leading to a siege of Thasos. These actions earned him the enmity of Stesimbrotus of Thasos, a source used by Plutarch. This event, the suppression of the Thasian rebellion, marked a significant step in the transformation of the Delian League from a voluntary alliance into an Athenian Empire, as Athens increasingly asserted its dominance over its allies.

2.4. Political Career and Foreign Policy

Cimon took an increasingly prominent role in Athenian politics, consistently aligning himself with the aristocratic faction and opposing the popular party, which sought to expand Athenian democracy. He was a staunch laconist, deeply fond of Sparta, and served as Sparta's representative in Athens. His admiration for Sparta was so profound that he named one of his sons Lacedaemonius.

In 463 BC, despite his military successes, Cimon was prosecuted by Pericles for allegedly accepting bribes from Alexander I of Macedon for not invading Macedon. According to Plutarch, Pericles was "very gentle with Cimon" during the trial, accusing him only once. Cimon, in his defense, emphasized that he had never been an envoy to wealthy kingdoms like Ionia or Thessaly, but rather to Sparta, whose frugality he admired and imitated. He argued that instead of enriching himself, he had enriched Athens with the spoils of war taken from the enemy. Ultimately, Cimon was acquitted.

In 462 BC, Cimon strongly advocated a policy of cooperation between Athens and Sparta. He convinced the Athenian Assembly to send military aid to Sparta, where the helots were in a major revolt (the Third Messenian War). Cimon personally commanded a force of 4,000 hoplites sent to Mount Ithome to assist the Spartan aristocracy. However, this expedition ended in humiliation for Cimon and Athens. The Spartans, fearing that the Athenians might eventually side with the helots, and perhaps distrusting them because they were not Dorians and possessed a "courage and spirit of innovation," sent the Athenian force back to Attica. This diplomatic snub severely damaged Cimon's popularity in Athens.

2.5. Exile and Return

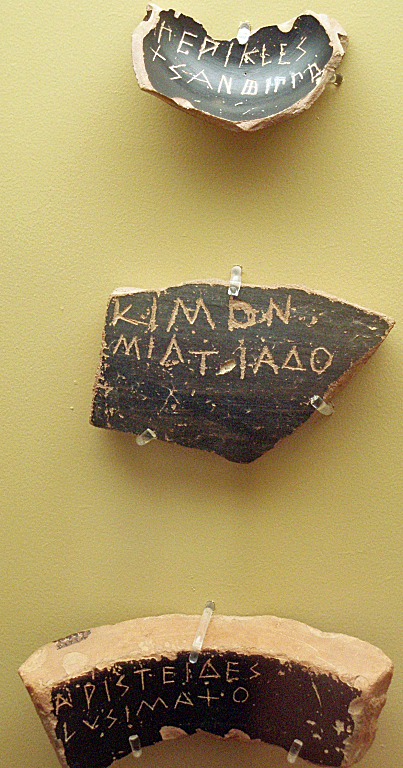

The insulting rebuff from Sparta led to the collapse of Cimon's political standing in Athens. As a result, he was ostracized from Athens for a period of ten years, beginning in 461 BC. Many ostraka bearing his name have survived, some with spiteful inscriptions such as "Cimon, son of Miltiades, and Elpinice too," referencing his haughty sister.

During Cimon's exile, the reformer Ephialtes, with the support of Pericles, took the lead in Athenian politics. They significantly reduced the power of the Areopagus, a council composed of former archons and a traditional stronghold of the oligarchy. Power was subsequently transferred to the citizens through the Council of Five Hundred, the Assembly, and the popular law courts, marking a significant advancement in Athenian democracy. Some of Cimon's key policies, including his pro-Spartan stance and his attempts at peace with Persia, were reversed during this period.

In 458 BC, Cimon sought to return to Athens to participate in the Battle of Tanagra against Sparta, but his offer of assistance was rejected. However, around 451 BC, Cimon was eventually recalled from exile, as Athens and Sparta had entered the First Peloponnesian War and Athens needed his military expertise. Although he did not regain his former level of political power, he successfully negotiated a five-year truce with the Spartans on Athens' behalf, a testament to his diplomatic skills and his enduring pro-Spartan connections.

2.6. Rebuilding Athens

Cimon utilized the considerable wealth he acquired from his numerous military exploits and the funds collected through the Delian League to finance extensive construction projects throughout Athens. These projects were vital for rebuilding the city after the devastating Achaemenid destruction of Athens during the Persian Wars.

He oversaw the expansion of the Acropolis and the fortification of the walls around Athens. Additionally, he initiated the construction of various public works, including new public roads, public gardens, and several political buildings. Cimon was also renowned for his personal generosity and public spirit. He reportedly removed the fences from his farm, allowing anyone to take as much of the harvest as they wished, and frequently provided meals for citizens. According to Cornelius Nepos, no one was without benefit from Cimon's wealth, highlighting his commitment to the welfare of the Athenian populace.

2.7. Death

Following his return and the negotiation of the truce with Sparta, Cimon proposed a new expedition to fight the Persians, who were moving a fleet against a rebellious Cyprus. With Pericles' support, Cimon set sail for Cyprus with a fleet of 200 triremes from the Delian League. From Cyprus, he dispatched sixty ships under Admiral Charitimides to Egypt to assist the revolt led by Inaros II in the Nile Delta. Cimon then used the remaining ships to support the uprising of the Cypriot Greek city-states.

In 450 BC, Cimon laid siege to Kition, a stronghold on the southwest coast of Cyprus held by Phoenician and Persian forces. He died during or shortly after the failed attempt to capture Kition. The exact cause of his death remains unrecorded. His death was kept secret from the Athenian army, who, under his 'command', subsequently achieved an important victory over the Persians at the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus. Cimon was later buried in Athens, where a monument was erected in his memory.

3. Historical Significance and Legacy

Cimon's legacy is defined by his profound impact on Athens' military and political landscape, encompassing both celebrated achievements that solidified Athenian power and controversial domestic policies that clashed with the burgeoning democratic movement.

3.1. Major Achievements and Positive Evaluation

Cimon's enduring legacy is primarily rooted in his significant military accomplishments and his foreign policy, which greatly shaped Athens' rise to power. His decisive victories, particularly at the Battle of the Eurymedon, established Athenian naval supremacy and effectively ended direct Persian military aggression against Greece. Through his leadership of the Delian League, he transformed it into a powerful maritime empire, securing Athenian dominance in the Aegean Sea.

Beyond his military prowess, Cimon contributed significantly to Athenian prosperity and public welfare. He generously funded numerous public works, including the expansion of the Acropolis and the city walls, as well as the construction of public roads, gardens, and political buildings, which were crucial for rebuilding Athens after the Persian Wars. His personal generosity, such as allowing public access to his farm's harvest and providing meals, fostered a sense of public spirit and goodwill. Historians like Plutarch regarded Cimon as fully equal to Themistocles and his own father, Miltiades, in all qualities demanded by war. His foreign policy, based on continued resistance to Persia and the recognition of Athens as the dominant sea power and Sparta as the dominant land power, is also credited with significantly delaying the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.

3.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his military successes and public generosity, Cimon's domestic policy was consistently anti-democratic, a stance that ultimately failed in the face of the rising democratic movement in Athens. He firmly supported the aristocratic faction and actively opposed reforms that sought to expand the power of the popular party and the Athenian populace. His political rivalry with figures like Pericles and his opposition to the democratic reforms championed by Ephialtes highlight his conservative leanings and his efforts to maintain aristocratic control over Athenian institutions.

Cimon's pro-Spartan foreign policy, while aiming for cooperation between the two leading Greek states, led to a major political setback. The humiliating rejection of Athenian aid by Sparta during the Third Messenian War severely damaged his popularity and directly led to his ostracism in 461 BC. This event paved the way for the democratic reforms under Ephialtes and Pericles, which dismantled the power of the aristocratic Areopagus. Furthermore, controversies surrounded his personal life, including accusations of an incestuous relationship with his sister Elpinice, which, while potentially political slander, contributed to his public image. His decision to name his sons with "foreign-influenced" names like Lacedaemonius was also criticized by opponents like Pericles, underscoring his aristocratic and somewhat detached perspective from the burgeoning Athenian democratic identity.