1. Early Life

Chūya Nakahara's early life was marked by a strict upbringing, profound family events, and an early awakening to the world of literature.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

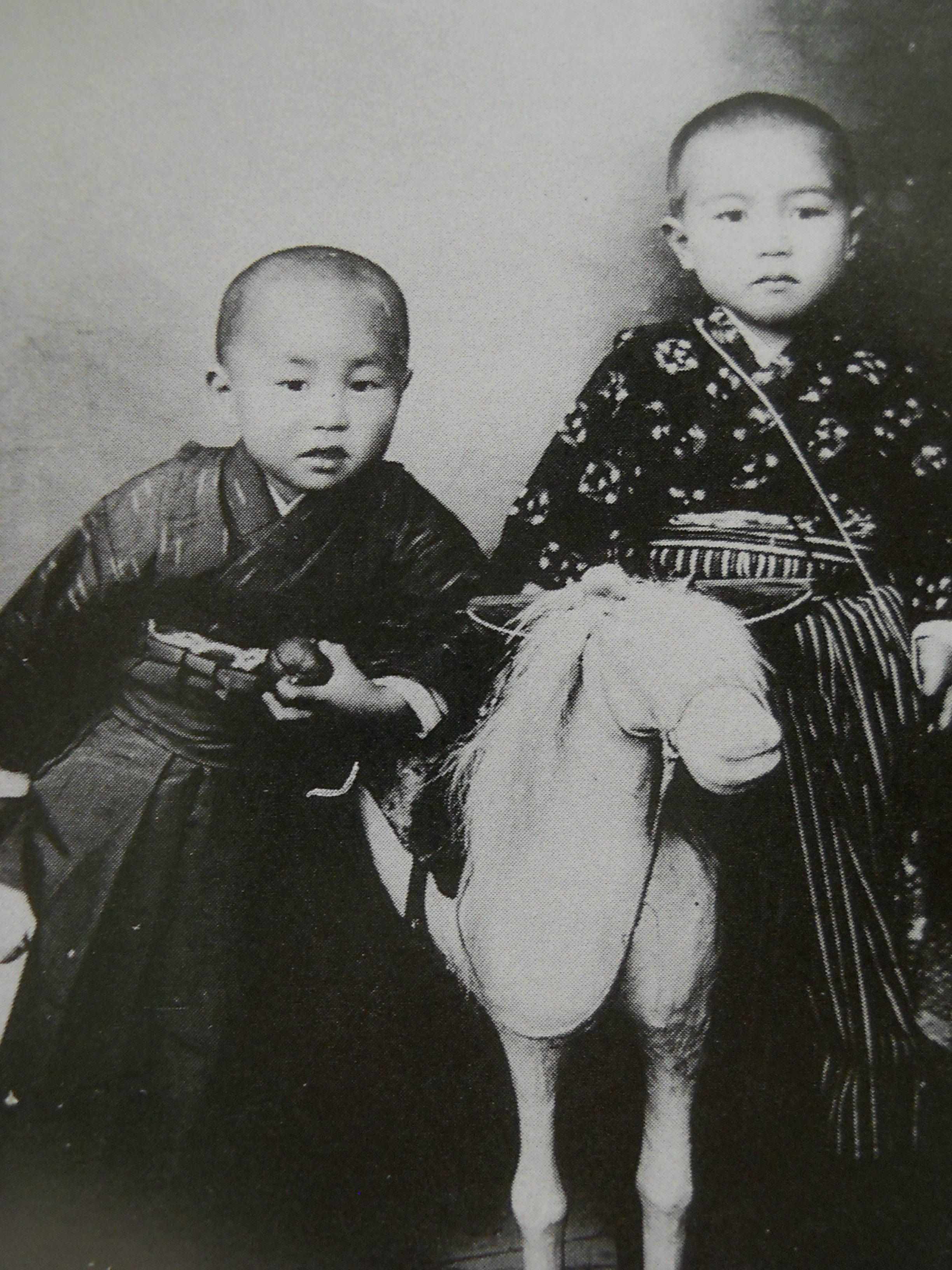

Chūya Nakahara was born on April 29, 1907, at the Nakahara Clinic in {{lang|ja|山口市|Yamaguchi City|Yamaguchi-shi}}, then Shimounoryo Village, Kifuku District, Yamaguchi Prefecture (modern-day Yuda Onsen). His father, Kensuke Kashimura, was a highly decorated army doctor. After Chūya's birth, Kensuke married Fuku Nakahara and was adopted into the Nakahara family, leading to the family's surname officially changing to Nakahara. His parents, who had been childless for six years, were overjoyed by the birth of their first son, celebrating for three days. His father, stationed in Ryojun (modern-day Lushun, China), named him "Chūya" via letter. When Chūya was six months old, his mother Fuku and grandmother Sue traveled to Ryojun to join Kensuke. The family later followed Kensuke's military assignments to Hiroshima and Kanazawa, before returning to Yamaguchi in 1914. In 1917, Kensuke inherited and re-established the Nakahara Clinic at the site where the Nakahara Chūya Memorial Hall now stands.

1.1.1. Childhood and Upbringing

As the eldest son of a prominent doctor, Nakahara was expected to follow in his father's footsteps, which led to a very strict upbringing. His parents, particularly his father Kensuke, had high expectations and imposed rigorous disciplinary measures that prevented him from experiencing an ordinary childhood. For instance, Kensuke, concerned about the morals of the town, forbade Chūya from playing outside with children from different social classes. Unlike his younger brothers, Chūya was not allowed to bathe in the river due to his father's fear of drowning. Severe punishments were common, including being made to stand upright facing a wall, with any sudden movement resulting in a cigarette ember burn on his heel. The most significant punishment, which Chūya received dozens of times more than his brothers, was being confined to sleep in the cold barn. These measures were intended to prepare him to become the head of the family and follow his father's profession.

1.1.2. Awakening to Literature

Chūya's academic performance was initially excellent; he was called a "prodigy child" during his elementary school years. However, a profound event in 1915, the death of his younger brother Tsugurō from meningitis at the age of four (or eight, according to some accounts), served as a pivotal moment, awakening him to literature. Driven by grief, he turned to composing poetry. He submitted his first three verses to a women's magazine, Fujin Gahō, and a local newspaper, Bōchō Shinbun, in 1920 while still in elementary school, where they were published. He also joined the Sugurono-no-kai tanka society and published 28 of his tanka in a collection titled "Onsen-shū." From this point forward, he began to rebel against his father's strictness, neglecting his studies, which caused his grades to drop. He became increasingly absorbed in literature, and also started drinking and smoking. His father, greatly fearful of literature's influence, severely scolded him and again confined him to the barn upon discovering hidden fiction.

2. Education and Literary Beginnings

Nakahara's formal education was marked by early promise, rebellion, and significant artistic encounters that shaped his poetic identity.

2.1. Schooling and Academic Struggles

In April 1920, Nakahara entered Yamaguchi Prefectural Yamaguchi Junior High School with excellent grades, ranking 12th. However, his absorption in reading led to a rapid decline in his academic performance, falling to 80th and then 120th. His teachers' warnings to his parents resulted in a cut to his allowance, pushing him to rely on reading at bookstores and libraries. Despite a brief recovery to 50th place in his second semester, his grades plummeted further in his second year. By 1923, his academic decline culminated in his decision to deliberately fail his third-year examination. Upon receiving the news, Nakahara famously gathered his classmates, celebrated with "hurrahs," and tore up his answer sheet. His father, Kensuke, was devastated and deeply humiliated by his son's failure, punishing him by striking him and confining him to the barn on a cold March night. However, Nakahara remained defiant, refusing to return to the school. This forced his father to apologize for his "educational policy," leading to Chūya's transfer to Ritsumeikan Middle School in Kyoto in April 1923. There, he began living alone, although his family continued to financially support him until his death.

2.1.1. Encounters in Kyoto

In Kyoto, Nakahara discovered profound influences that would shape his poetic voice. In the autumn of 1923, he read {{lang|ja|高橋新吉|Takahashi Shinkichi|Takahashi Shinkichi}}'s {{lang|ja|ダダイスト新吉の詩|Dadaist Shinkichi no Shi|Dadaisuto Shinkichi no Shi}} ("The Poems of Dadaist Shinkichi"), which deeply shocked and inspired him, prompting him to resume writing poetry. He became deeply immersed in Dadaism, an artistic movement that earned him the affectionate nickname "Dada-san" among his peers. That winter, he met Yasuko Hasegawa, an actress three years his senior from the Hyōgenza theater company; they began living together in April 1924. Yasuko, who initially worked for Makino Production but was later dismissed, became financially dependent on Nakahara's family allowance. In 1924, Chūya also befriended the poet Tominaga Tarō, who, though six years his senior, visited Chūya's lodgings daily for discussions. Through Tominaga, Nakahara also connected with a group of university students from Kyoto Imperial University, attending art exhibitions and engaging in drinking sessions.

2.1.2. Move to Tokyo and Literary Circles

In 1925, after dropping out of middle school in his fourth year (which allowed him to take university entrance exams), Nakahara moved to Tokyo with Yasuko, intending to attend university. However, he was unable to take entrance exams for Nihon University or Waseda University due to missing documents or arriving late. He began receiving financial support from his family on the condition that he attend a preparatory school, but he dropped out of the Nihon University preparatory course in September 1926 without informing them. He then enrolled at Athénée Français to study French.

In Tokyo, through Tominaga Tarō, Nakahara met {{lang|ja|小林秀雄|Kobayashi Hideo|Kobayashi Hideo}}, an influential literary critic and a student at Tokyo Imperial University. A pivotal and painful event occurred in November 1925 when Yasuko Hasegawa left Chūya and began living with Kobayashi Hideo, a development that deeply affected Nakahara. This personal upheaval coincided with the death of his friend Tominaga Tarō from tuberculosis that same month. Nakahara's first published work, "The Deceased Tominaga" (夭折した富永Yōsetsu Shita TominagaJapanese), appeared in Yamamayu, a literary magazine that included contributions from Tominaga and Kobayashi. In December 1927, he met composer Saburō Moroi, who would later adapt several of his poems, including "Morning Song" ({{lang|ja|朝の歌|Asa no Uta|Asa no Uta}}) and "Deathbed" ({{lang|ja|臨終|Rinjū|Rinjū}}), to music. In April 1931, Chūya enrolled in the French language department of Tokyo Foreign Language College in Kanda, where he studied until March 1933, contemplating a career as a foreign service officer to facilitate overseas study.

3. Literary Career

Nakahara's literary career was marked by a blend of diverse influences, a unique poetic style, and significant contributions to Japanese poetry despite its brevity.

3.1. Poetic Influences

Initially, Nakahara expressed a preference for the traditional Japanese tanka format. However, during his teenage years, he became drawn to the modern free verse styles advocated by the Dadaist poets Takahashi Shinkichi and Tominaga Tarō. His move to Tokyo further broadened his literary horizons. He was notably introduced to the French Symbolist poets Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine by his friend and influential literary critic Kobayashi Hideo. Nakahara's engagement with Rimbaud went beyond mere poetic influence; he translated Rimbaud's works into Japanese, and the French poet's bohemian lifestyle also left a distinct mark on Nakahara's own personal conduct. Furthermore, Nakahara was profoundly impacted by Miyazawa Kenji's poetry collection, {{lang|ja|春と修羅|Haru to Shura|Haru to Shura}} ("Spring and Asura"), published in 1924. He felt a deep connection to its unique cosmic view and its rhythmic use of colloquial language, praising Kenji's "sentimental poetry" and expressing surprise that it had not been more widely read in Japan.

3.2. Poetic Style and Themes

Nakahara Chūya's poetry is often characterized as somewhat obscure, deeply confessional, and imbued with a pervasive sense of pain and melancholy, emotions that were constant throughout his life. His emotional range in his poems spanned "confusion, ennui, anger, gloom, and apathy." He frequently explored themes of solitude and the inherent darkness of life, while also expressing a childlike wonder about humanity and its connection to the external world. Raised in a predominantly Christian prefecture, Nakahara often questioned faith in his poems, delving into the spiritual realm and the concept of an unattainable "other world."

He skillfully adapted the traditional five and seven-syllable counts of Japanese haiku and tanka, often introducing variations to achieve a distinctive rhythmical and musical effect. This musicality was so pronounced that many of his poems were later set to music, suggesting a deliberate calculation from the outset. A striking example of his unique style is the onomatopoeia "yuaan yuyoon yuyuyon" ({{lang|ja|ゆあーん ゆよーん ゆやゆよん|yuaan yuyoon yuyuyon|yuaan yuyoon yuyuyon}}) from his famous poem "Circus" ({{lang|ja|サーカス|Sākasu|Sākasu}}), which he would famously recite with closed eyes and pursed lips.

3.3. Major Works

Nakahara Chūya published only one poetry anthology during his lifetime, {{lang|ja|山羊の歌|Yagi no Uta|Yagi no Uta}} ("Poems of the Goat"). This collection, self-financed and limited to 200 copies, was published in December 1934 by Bunpodō, with a luxurious binding designed by Takamura Kōtarō. The book was sold for 3.5 JPY.

A second collection, {{lang|ja|在りし日の歌|Arishi Hi no Uta|Arishi Hi no Uta}} ("Songs of Bygone Days"), was meticulously edited by Nakahara himself just before his death and published posthumously in April 1938 by Sōgensha.

Beyond his original poetry, Nakahara was also a notable translator of French literature. His most significant translations include {{lang|ja|ランボオ詩集〈学校時代の歌〉|Rimbaud Shishū (Gakkō Jidai no Uta)|Rambō Shishū (Gakkō Jidai no Uta)}} ("Poems of Rimbaud: Songs of School Days"), published by Mikasa Shobō in December 1933, which was his first commercial publication and established him as a key interpreter of Rimbaud in Japan. He also published {{lang|ja|ランボオ詩抄|Rimbaud Shishō|Rambō Shishō}} in 1936 and another {{lang|ja|ランボオ詩集|Rimbaud Shishū|Rambō Shishū}} with Noda Shoten in 1937, which was a commercial success. Additionally, he translated works by André Gide, such as Calendar in the 1934 Gide Complete Works.

3.4. Journals and Collaborations

Nakahara's literary engagement extended to various journals and collaborations with other writers and artists. In April 1929, he co-founded the poetry journal Hakuchigun (Group of Idiots) with Kawakami Tetsutarō, Ōoka Shōhei, Murai Yasuo, Uchiumi Seiichirō, Abe Rokurō, Furuya Tsunatake, Yasuhara Yoshihiro, and Tominaga Jirō. This journal published six issues over a year before ceasing publication due to internal disagreements and difficulties in gathering manuscripts, marking a period of reduced poetic output for Nakahara. Despite initial rejections from many major publishers, his works found acceptance primarily in smaller literary magazines such as Yamamayu, where his first work, "The Deceased Tominaga," was published. On occasion, established journals like Shiki and Bungakukai would also publish his works. He also participated in the literary magazine Kigen starting in May 1933 and Rekitei from May 1935.

His poems were notable for their musicality, and many were adapted into songs. In May 1928, composer Saburō Moroi set Nakahara's poems Asa no Uta ("Morning Song") and Rinjū ("Deathbed") to music, which were performed at the second concert of the avant-garde music group Surya, an extremely rare occurrence for an unknown poet's work to be set to music before their official publication in a poetry collection. Moroi also composed music for Nakahara's "Empty Autumn" (Karashiki Aki), "My Sister" (Imo yo), and "Spring and Baby" (Haru to Akanbō), with "My Sister" being broadcast on JOBK (NHK Osaka). Another Surya member, Uchiumi Seiichirō, composed music for "Homecoming" (Kikyō) and "Lost Hope" (Usenishi Kibō) in 1930.

4. Personal Life and Struggles

Chūya Nakahara's personal life was marked by complex relationships, profound family tragedies, and struggles with his own health and inner demons.

4.1. Key Relationships

Nakahara's relationships were often intense and tumultuous. His most significant early relationship was with Yasuko Hasegawa, an actress whom he met in Kyoto in 1923 and with whom he began living in April 1924. This cohabitation deeply impacted his life and work. However, in November 1925, Yasuko left Nakahara and began a relationship with his close friend, the literary critic Kobayashi Hideo. Despite this painful betrayal, Nakahara and Kobayashi remained close friends throughout their lives.

In December 1933, Nakahara married Takako Ueno, a distant relative. This marriage was notable for Chūya's unusual obedience to his mother's wishes, unlike his usual defiant nature. The wedding ceremony and a grand reception were held for close family at Nishimuraya, a local hot spring inn in Yuda Onsen.

Beyond these romantic relationships, Nakahara maintained various literary friendships. He met Takahata Hiroatsu in 1928 and frequently visited his atelier. He also had complex interactions with figures like Aoyama Jirō, Ibuse Masuji, Sakaguchi Ango, and Dazai Osamu, often characterized by his confrontational and challenging nature when under the influence of alcohol. For example, Dazai Osamu initially invited Nakahara to collaborate on a literary magazine but later rejected him, calling him "slug-like." Yoshida Hidekazu recounts an instance where he took a drunken Nakahara home to listen to music.

4.2. Family and Children

After marrying Takako Ueno, Nakahara's first son, Fumiya ({{lang|ja|文也|Fumiya|Fumiya}}), was born in October 1934 in his hometown. Chūya deeply adored Fumiya, often spending time watching him play. However, tragedy struck in November 1936 when Fumiya died at the age of two from juvenile tuberculosis. Nakahara was profoundly devastated, nursing his son for three days without sleep and refusing to let go of his body at the funeral. He mourned intensely for 49 days, calling a monk daily to chant sutras and remaining by Fumiya's memorial tablet.

His second son, Yoshimasa ({{lang|ja|愛雅|Yoshimasa|Yoshimasa}}), was born in December 1936, shortly after Fumiya's death. However, this birth did little to alleviate Nakahara's grief. Tragically, Yoshimasa also died of the same illness in January 1938, approximately three months after Nakahara's own passing.

Nakahara's relationship with his parents was also complex. His father, Kensuke, passed away in May 1928. Chūya did not attend the funeral, as his mother, Fuku, concerned about social appearances given his academic failures and bohemian lifestyle, fabricated a story of his illness. His mother, Fuku, played a significant role throughout his life, frequently providing him with substantial monthly allowances, often exceeding 100 JPY, to support his life in Tokyo, despite her concerns about his lifestyle and his pretense of attending university. She lived until 1980.

Chūya had several younger brothers. Tsugurō ({{lang|ja|亜郎|Tsugurō|Tsugurō}}) died at age four or five in 1915, a death that profoundly impacted Chūya and sparked his poetic endeavors. Kōzō ({{lang|ja|恰三|Kōzō|Kōzō}}), his second younger brother, died of lung tuberculosis at age 20 in September 1931. Chūya, who had missed his father's death, explicitly asked his mother to allow him to see Kōzō's face before cremation, a request his mother honored. His other brothers included Shirō ({{lang|ja|思郎|Shirō|Shirō}}), who later became a scholar of Chūya's work; Gorō ({{lang|ja|呉郎|Gorō|Gorō}}), who became a doctor and reopened the Nakahara Clinic; and Jūrō ({{lang|ja|拾郎|Jūrō|Jūrō}}), who was adopted into the Itō family and later became a harmonica player.

4.3. Health and Personal Demons

Nakahara grappled with significant health issues and personal demons throughout his adult life. He began drinking and smoking during middle school, and his struggles with alcoholism became severe. His drunken behavior, often characterized by shūran (alcohol-induced rampages), was infamous. At age 22, after a night of drinking with Hakuchigun members Murai Yasuo and Abe Rokurō, he smashed streetlights with an umbrella, leading to his arrest and a 15-day detention, which left him with a lasting fear of the police. His behavior at bars, such as the "Windsor" frequented by young writers like Kobayashi Hideo and Ibuse Masuji, often involved provoking fights and harassing patrons, contributing to the bar's closure within a year. He physically assaulted Ōoka Shōhei and threatened Nakamura Mitsuo with a beer bottle while drunk.

Following the death of his first son, Fumiya, in November 1936, Nakahara suffered a severe nervous breakdown. He exhibited signs of mental instability, including compulsive thoughts, hallucinations, and child regression, prompting his wife Takako to contact his mother, Fuku, and brother, Shirō, who traveled to Tokyo to help. In January 1937, his mother had him admitted to the Nakamura Kokyo Sanatorium in Chiba, a psychiatric facility where he received occupational therapy and guidance in journaling. He was released in February 1937 but returned home distraught, believing he had been tricked into hospitalization. Unable to bear the memories of Fumiya in their Tokyo home, he moved to a rented house within the grounds of Jufukuji Temple in Kamakura. In September 1937, he complained of pain in his left middle finger, diagnosed as gout. He also experienced visual disturbances, seeing power lines double, and struggled with walking, requiring a cane.

5. Death

Chūya Nakahara's life was tragically cut short at the age of 30. On October 4, 1937, his health further deteriorated, and he collapsed in front of Kamakura Station. He was hospitalized the following day at Kamakura Yōjōin (now Tokushūkai Kiyokawa Hospital). Initially suspected of having a brain tumor, he was later diagnosed with acute meningitis, which is now understood to have been tubercular meningitis.

As his condition worsened, his mother Fuku and brother Shirō rushed to his side on October 15, finding him already in a state of confused consciousness. His friends, including Kobayashi Hideo, who took a week off from Meiji University to stay by his bedside, and Kawakami Tetsutarō, who visited daily from Tokyo, were also present. Chūya Nakahara passed away peacefully without much suffering at 0:10 AM on October 22, 1937, at Kamakura Yōjōin.

His wake was held for two days at his home, followed by a farewell ceremony at the main hall of Jufukuji Temple on October 24. His body was cremated at Seikōsha in Zushi Town. Approximately one month later, his ashes were interred in the family grave at Kyootsuka Cemetery in Yamaguchi City, near the Yoshiki River, a site that appears in his uncollected poem "Cicadas" ({{lang|ja|蟬|Semi|Semi}}). Tragically, his second son, Yoshimasa, also died from the same illness in January 1938, about three months after Chūya's death.

6. Legacy and Impact

Despite his short life and limited mainstream recognition during his lifetime, Chūya Nakahara's work has achieved widespread posthumous acclaim, leaving a significant and lasting impact on Japanese literature and various forms of modern culture.

6.1. Posthumous Recognition

During his lifetime, Chūya Nakahara was not widely considered a mainstream poet. Only one of his poetry anthologies, {{lang|ja|山羊の歌|Yagi no Uta|Yagi no Uta}} ("Poems of the Goat"), was published in 1934, a self-financed edition of just 200 copies. He completed editing a second collection, {{lang|ja|在りし日の歌|Arishi Hi no Uta|Arishi Hi no Uta}} ("Songs of Bygone Days"), shortly before his death.

However, after his passing, the emotional and lyrical nature of his verses gained significant and ever-increasing popularity, especially among young people. His work is now a subject of study in Japanese schools, and his iconic portrait, depicting him in a hat with a vacant stare, is widely recognized. Kobayashi Hideo, to whom Nakahara entrusted the manuscript for Arishi Hi no Uta on his deathbed, was instrumental in the posthumous promotion of his works. Similarly, Ōoka Shōhei took on the crucial task of collecting and editing The Complete Works of Nakahara Chūya, a comprehensive collection that includes the poet's uncollected poems, journals, and numerous letters. This three-volume complete works, published in 1951, generated significant public reaction. Subsequent editions and anthologies of his poetry have ensured his widespread readership. After World War II, Bungakukai, Kigen, and Shiki magazines organized tribute issues, further solidifying his critical reputation.

6.2. The Nakahara Chūya Prize

In honor of his enduring legacy, the Nakahara Chūya Prize ({{lang|ja|中原中也賞|Nakahara Chūya Shō|Nakahara Chūya Shō}}) was established in 1996 by Yamaguchi City, with the support of publishers Seidosha and Kadokawa Shoten. This prestigious award is presented annually to an outstanding collection of contemporary poetry that is characterized by a "fresh sensibility" ({{lang|ja|新鮮な感覚|shinsen na kankaku|shinsen na kankaku}}). The winner receives a cash prize of 1.00 M JPY and, for several years, the winning collection was also published in an English language translation, though this practice has recently been discontinued. The main prize is a bronze bust of Nakahara Chūya, created by Takahata Hiroatsu.

It is important to note that this current prize is distinct from an earlier "Nakahara Chūya Prize" initiated by Yasuko Hasegawa and her husband Nakagaki Takenosuke shortly after his death, which ran for only three years (1938-1940) and recognized poets such as Tatsuhara Michizō, Takamori Fumio, Sugiyama Heiichi, and Hiraoka Jun.

6.3. Cultural Influence

Nakahara Chūya's poetry has exerted a lasting influence across various forms of modern culture, including music, anime, and other artistic expressions.

Many composers have set his poems to music. Saburō Moroi was an early adapter, composing for "Morning Song" and "Deathbed" which were performed in 1928, and also for "Empty Autumn," "My Sister," and "Spring and Baby." Uchiumi Seiichirō composed for "Homecoming" and "Lost Hope" in 1930. Posthumously, numerous composers, including Ishiwatari Hideo, Shimizu Osamu, Tada Takehiko, and Ōoka Shōhei (who composed for "Evening Glow" and "Snowy Evening"), have contributed to a vast body of classical and choral songs. His works have also inspired popular music, including enka and folk songs. The acid-folk singer Kazuki Tomokawa recorded two albums, Ore no Uchide Nariymanai Uta and Nakahara Chuya Sakuhinnshu, using Nakahara's poems as lyrics, and continues to adapt his poetry. The Kaientai folk group's song "I've Come a Long Way" (Omoeba Tooku e Kita Monda) is widely believed to be inspired by Nakahara's "Naïve Song" (Ganzei Uta). The poem "Defiled Sadness..." ({{lang|ja|汚れつちまつた悲しみに|Yogorechimatta Kanashimi ni|Yogorechimatta Kanashimi ni}}) has been set to music by Ōtaka Shizuru for NHK's children's program Nihongo de Asobo and by singer Kuwata Keisuke. The phrase also appears in GLAY's song Kuroku Nure! and in dialogue in GRANRODEO's song SUGAR. Ishikawa Koji of the band Tama set "Moonlight" (Tsuki no Hikari) to music. More recently, composer Shōichi Yabuta from Tatsuno City has composed numerous songs based on Nakahara's poems.

Nakahara's influence extends to visual media and games. In the anime Space Battleship Yamato 2199, the character Shiro Sanada frequently carries a collection of Nakahara's poetry. He is also the inspiration for a character of the same name in the popular anime and manga series Bungo Stray Dogs, whose special ability is named "Defiled Sadness" and is voiced by Taniyama Kishō (GRANRODEO's vocalist). He also inspired a character in the game and anime Bungou to Alchemist. His life has been depicted in films such as Hotaru no Hito (1986) and Yukite Kaeranu (2025), and TV dramas like Yogorechimatta Kanashimi ni (1990). A documentary, ETV Feature: In the Middle of Great Tokyo, Alone, was broadcast by NHK in 2007 for his 100th birth anniversary. Additionally, a poetry monument featuring his work "Kuwana Station" stands at Kuwana Station.

6.4. Critical Reception

During his lifetime, Nakahara was highly valued by his close circle of friends and influential literary figures, including Kobayashi Hideo and Kawakami Tetsutarō. Contemporary poets such as Murō Saisei, Kusano Shinpei, and Hagiwara Sakutarō recognized the unique and precious quality of his lyrical world.

After his death, the literary world quickly moved to recognize his talent. Bungakukai, Kigen, and Shiki magazines promptly planned and published tribute issues, sustaining the critical assessment of Nakahara's work. The turning point in his posthumous recognition came after World War II, with the publication of Nakahara Chūya Shishū (Collected Poems of Chūya Nakahara) by Sōgensha in 1947, edited and annotated by the repatriated Ōoka Shōhei. This collection garnered a significant public response. Subsequently, Rimbaud Shishū was reissued in 1949, and The Complete Works of Nakahara Chūya (three volumes) was published in 1951. Since then, Nakahara's poetry has been included in various literary collections and anthologies, gaining a broad and ever-growing readership and cementing his unique position in Japanese literature.

7. Timeline

- 1907**: Born April 29 in Shimounoryo Village (now Yamaguchi City, Yuda Onsen), Yamaguchi Prefecture. Father Kensuke is an army doctor in Ryojun.

- 1909**: Moves to Hiroshima with family due to father's transfer.

- 1912**: Moves to Kanazawa.

- 1914**: Returns to Yamaguchi. Enters Shimounoryo Elementary School.

- 1915**: Younger brother Tsugurō dies. Begins writing poetry, which he later states was his first poetic endeavor. Father Kensuke returns to Yamaguchi; the family formally adopts the Nakahara surname.

- 1917**: Father Kensuke retires from military service and inherits the Nakahara Clinic.

- 1918**: Transfers to Yamaguchi Normal School Affiliated Elementary School.

- 1920**: His tanka poems are published in Fujin Gahō and Bōchō Shinbun. Enters Yamaguchi Prefectural Yamaguchi Junior High School.

- 1922**: Publishes Sugurono, a collection of tanka, with two friends.

- 1923**: Fails his third-year examination and transfers to Ritsumeikan Middle School in Kyoto. Becomes deeply influenced by Takahashi Shinkichi's Dadaist poetry and begins writing poetry again. Meets actress Yasuko Hasegawa.

- 1924**: Begins living with Yasuko Hasegawa. Meets poet Tominaga Tarō, developing an interest in French poetry.

- 1925**: Moves to Tokyo with Yasuko, intending to attend university but failing to enroll. Meets Kobayashi Hideo. In November, Yasuko leaves him for Kobayashi. Tominaga Tarō dies.

- 1926**: Drops out of Nihon University preparatory course. Begins attending Athénée Français to study French. His first published work, "The Deceased Tominaga," appears in the Yamamayu journal.

- 1927**: Meets composer Saburō Moroi.

- 1928**: Saburō Moroi sets Nakahara's poems "Morning Song" and "Deathbed" to music, performed at the Surya concert. Father Kensuke dies; Chūya does not attend the funeral. Meets Takahata Hiroatsu.

- 1929**: Co-founds the literary journal Hakuchigun (Group of Idiots) with Kawakami Tetsutarō and Ōoka Shōhei, publishing six issues until its discontinuation the following year.

- 1930**: Enrolls in Chuo University preparatory course. Yasuko Hasegawa gives birth to a son with Yamakawa Yukiyo; Nakahara names the child Shigeki and cares for him.

- 1931**: Enters the French language department of Tokyo Foreign Language School. Younger brother Kōzō dies of lung tuberculosis.

- 1932**: Plans the publication of his first poetry collection, Yagi no Uta, but fails to secure funding. Experiences a nervous breakdown.

- 1933**: Graduates from Tokyo Foreign Language School. His translation of Rimbaud Shishū (Gakkō Jidai no Uta) is published by Mikasa Shobō. Marries Takako Ueno.

- 1934**: First son, Fumiya, is born in October. Yagi no Uta is published in December.

- 1935**: Yagi no Uta receives positive reviews. Begins publishing new poems monthly in Bungakukai. Joins the Rekitei literary group.

- 1936**: Unsuccessfully interviews for a position at NHK. Receives first royalties from Rimbaud Shishō. Son Fumiya dies in November, leading to Nakahara's severe mental instability. Second son, Yoshimasa, is born in December.

- 1937**: Hospitalized at Nakamura Kokyo Sanatorium in Chiba in January, discharged in February. Moves to Kamakura. Publishes Shunka Kyōsō ("Rhapsody of Spring Day") in Bungakukai. Rimbaud Shishū is re-published by Noda Shoten. Completes the manuscript for Arishi Hi no Uta and entrusts it to Kobayashi Hideo. Dies on October 22 from tubercular meningitis at the age of 30. Buried in Yamaguchi City.

- 1938**: Second son Yoshimasa dies in January. Arishi Hi no Uta is published in April.

- 1972**: His birthplace in Yuda Onsen is destroyed by fire.

- 1994**: Nakahara Chūya Memorial Museum opens at the site of his birthplace in Yuda Onsen, Yamaguchi City.

- 1996**: The Nakahara Chūya Prize is established by Yamaguchi City.