1. Life and Background

Jeong Yagyong's early life and family background provided the intellectual and social context for his later development as a leading reformist thinker of the Joseon Dynasty.

1.1. Birth and Early Life

Jeong Yagyong was born in 1762 in Mahyeon (馬峴), Choebu-myeon, Gwangju-bu, Gyeonggi Province, which is now Neungnae-ri, Joan-myeon, Namyangju, Gyeonggi Province. The area, known as Duamulmeori, is where the South and North Han Rivers converge. He was the fourth son among four sons and two daughters born to his father's second wife.

In the year of his birth, Crown Prince Sado was executed by his father, King Yeongjo. Deeply affected by this event, Jeong Yagyong's father, Jeong Jae-won, resigned from his official position and returned to his hometown. In light of this, Jeong Jae-won gave his newborn son the childhood name Kwinong (귀농GwinongKorean), meaning "back to farming," symbolizing a wish for his son to avoid political strife and live a humble life in the countryside.

Jeong Yagyong displayed exceptional intellectual abilities from a young age. His father was impressed by his powers of observation by age six. By age seven, he had composed a poem about the sea, and by age nine, he had compiled a small collection of his childhood poems titled Sammija-jip (삼미자집Sammija-jipKorean), though this work is no longer extant. His nickname "Sammi" (삼미SammiKorean, lit. "three eyebrows") originated from scars on his eyebrow caused by smallpox during his childhood. He survived the illness thanks to the treatment of Yi Heon-gil, a royal physician. This experience later inspired Jeong Yagyong to write Ma-gwa Hoetong, a more advanced treatise on measles and smallpox, based on Yi Heon-gil's Majin Gibang. He also wrote Mongsujeon, a biography of Yi Heon-gil.

His mother passed away when he was nine, and he was raised with care by his eldest sister-in-law, Lady Jeong of Gyeongju, and his stepmother, Lady Kim. By age ten, he had reportedly written so many compositions, imitating classics, that they stacked as high as his own height.

1.2. Family Background

Jeong Yagyong belonged to the Naju Jeong clan, though their ancestral home was originally in Aphae, Sinan County, South Jeolla Province, which was historically part of Naju-mok during the Joseon Dynasty. His ancestors had moved to Seoul during the early Joseon period from Baecheon, Hwanghae Province.

The Naju Jeong clan was renowned for its academic and official achievements. His 11th-generation ancestor, Jeong Ja-geup, served as a Gyori in the Seungmunwon, and for eight consecutive generations, his ancestors passed the civil service examinations and were appointed to prestigious positions in the Hongmungwan (Office of Special Advisors), which was considered one of the Three Offices (Samgwan), symbolizing the highest academic and administrative integrity. Jeong Yagyong proudly referred to his lineage as "Paldadeokdang" (팔대옥당PaldadeokdangKorean, lit. "Eight Generations of Jade Hall"), signifying his family's distinguished academic heritage. The Hongmungwan, along with the Saheonbu and Saganwon, formed the Three Offices, crucial departments that only highly educated scholar-officials could enter. High-ranking officials like state councilors and ministers almost without exception passed through this office, making it a symbol of integrity in Joseon.

However, the family's fortunes declined after the Gapsul Hwanguk in 1694, when the Westerners (Seoin) faction gained power, leading to the downfall of the Southerners (Namin) faction, to which the Jeong family belonged. His fifth-generation ancestor, Jeong Si-yun, moved to Mahyeon-ri in Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province, in 1699 to avoid political strife. For three generations, including his great-great-grandfather Jeong Do-tae, great-grandfather Jeong Hang-sin, and grandfather Jeong Ji-hae, the family did not hold high office, though his great-great-grandfather and great-grandfather passed the *jinsa* (licentiate) examination, and his grandfather attained the rank of Tongdeokrang.

His father, Jeong Jae-won (정재원Jeong Jae-wonKorean; 1730-1792), initially passed the *saengwonsi* (licentiate examination) in March 1762 but did not pursue further civil service examinations, despite encouragement from his relative by marriage, Chae Je-gong. He later entered officialdom through a minor appointment due to financial difficulties, serving as a Jwarang in the Board of Taxation, Ulsan Busasa, and Jinju Moksa (a third-rank magistrate). Jeong Jae-won had an eldest son, Jeong Yak-hyeon (정약현Jeong Yak-hyeonKorean; 1751-1821), from his first wife, Lady Nam of Uiryeong. With his second wife, Yun So-on (윤소온Yun So-onKorean; 1728-1770), a descendant of the renowned scholar-poet Yun Seon-do and granddaughter of the painter Yun Du-seo from the Haenam Yun family, he had three sons-Jeong Yak-jeon (정약전Jeong Yak-jeonKorean; 1758-1816), Jeong Yak-jong (정약종Jeong Yak-jongKorean; 1760-1801), and Jeong Yagyong-and one daughter. The intellectual interests of Jeong Yagyong can also be traced to the influence of Udam Jeong Si-han (우담 정시한Udam Jeong Si-hanKorean; 1625-1707) of the same clan, who taught Jeong Si-yun and Jeong Do-tae.

1.3. Education and Intellectual Influences

Jeong Yagyong's early education was primarily guided by his father, Jeong Jae-won, whom he accompanied to various official postings. Unlike his elder brother Jeong Yak-jeon, who studied under Gwon Cheol-shin, a scholar of Seongho Yi Ik's lineage, Jeong Yagyong was largely self-taught, although he was deeply influenced by Yi Ik's scholarship through his interactions with Yi Ga-hwan and Yi Seung-hun.

In 1776, at the age of 14, Jeong Yagyong married Lady Hong Hwabo of the Pungsan Hong clan and moved to Seoul, where his father had secured an appointment. This move allowed him to frequently visit his wife's family, providing opportunities to engage with the scholarly circles in the capital. That same year, he met Yi Ga-hwan (이가환Yi Ga-hwanKorean; 1742-1801), a grand-nephew of Yi Ik, and Yi Seung-hun (1756-1801), Yi Ga-hwan's nephew by marriage. Both were central figures in preserving and developing Yi Ik's academic traditions. Through them, Jeong Yagyong gained access to Yi Ik's unpublished works and became deeply impressed by the Silhak school of thought, resolving to dedicate his life to similar practical studies. This early exposure to the reformist theories of the Geungi school (a branch of Silhak) significantly shaped his intellectual development. In 1777, at age 15, he accompanied his father, who was appointed Hwasun County Magistrate, to Dongnimsa Temple in northern Hwasun, where he devoted himself to studying books with his brother Jeong Yak-jeon. In 1780, at age 18, he moved to Yecheon when his father was appointed Yecheon County Magistrate in Gyeongsang Province.

In 1783, Jeong Yagyong passed the *chinsagwa* (literary licentiate examination), which qualified him for entry into the Sungkyunkwan, the highest national educational institution. At Sungkyunkwan, he consistently achieved top scores in monthly and ten-day examinations, earning rewards of books, paper, and brushes, and gaining the special favor of King Jeongjo. This period of rigorous academic pursuit further solidified his foundation in classical studies and prepared him for his future official career. Jeong Yagyong's study method was known as *Choseobeop* (초서법ChoseobeopKorean), which involved selectively copying important parts of books rather than transcribing them entirely.

2. Official Career and Political Activities

Jeong Yagyong's official career was marked by his close relationship with King Jeongjo and his dedication to administrative reform, though it was also fraught with political challenges from opposing factions.

2.1. Civil Service Examinations and Entry into Government

In 1789, at the age of 27, Jeong Yagyong successfully passed the *daegwa* (higher civil service examination), marking his official entry into government service. He was immediately appointed to a position in the Office of Royal Decrees (Gyujanggak), a prestigious institution under King Jeongjo's direct patronage, alongside five other members of the Southerner (Namin) faction. This rapid advancement and the king's favor towards the Southerners alarmed members of the opposing Old Doctrine (Noron) faction, who viewed the growing influence of the Southerners, particularly their interest in Western learning and Catholicism, as a threat to their established power.

2.2. Relationship with King Jeongjo and Royal Service

Jeong Yagyong enjoyed a remarkably close and trusting relationship with King Jeongjo, who recognized his exceptional intellect and reformist zeal. The king often sought his counsel and entrusted him with significant state projects. Compared to Hong Guk-yeong, another close confidant of King Jeongjo, Jeong Yagyong was known as a moderate figure without much ambition, though he was reportedly not skilled in martial arts.

One notable project was Jeong Yagyong's design of a pontoon bridge across the Han River, which facilitated royal processions and demonstrated his engineering acumen. In 1791, he participated in the design of the Hwaseong Fortress in Suwon, a major undertaking for King Jeongjo. For this project, Jeong Yagyong invented the Geojunggi (거중기GeojunggiKorean), a type of crane utilizing leverage mechanics and pulleys (활차녹로, 활차녹로hwalcharokroKorean), which significantly reduced construction time and costs, saving an estimated 40,000 *gwan*. His innovative techniques drew inspiration from European, Chinese, and Japanese sources, including the Gujin Tushu Jicheng and Johann Schreck's Qiqi Tushuo, which King Jeongjo provided to him for study after Jeong Yagyong proposed fortress reforms in 1792. The Hwaseong Fortress, a UNESCO World Heritage site, stands as a testament to his engineering genius.

In 1791, Jeong Yagyong was briefly exiled to Haemi in Seosan due to accusations from the Gongseo faction during the Shinhae Persecution, but he was released after 11 days due to King Jeongjo's intervention. He subsequently served in key positions in the Saganwon and Hongmungwan.

In 1794, after several promotions, King Jeongjo appointed him as a secret royal inspector (Amhaengeosa) for Gyeonggi Province, tasking him with investigating reports of corruption in Yeoncheon and Saknyeong. In 1795, Jeong Yagyong played a crucial role in helping the king decide on a new honorary title for his father, Crown Prince Sado, an undertaking fraught with political sensitivities between the Expediency and Principle subfactions. The Southerners, including Jeong Yagyong, strongly supported the king's desire to honor Sado, earning Jeongjo's gratitude. However, due to continued accusations from his enemies regarding his alleged support for pro-Western Catholics, Jeongjo found it prudent to temporarily send him away from court, appointing him superintendent of the post station at Geumjeong, South Pyeongan Province. Here, Jeong Yagyong actively worked to persuade Catholics to renounce their faith and perform ancestral rites, demonstrating his public rejection of Catholicism, likely influenced by the Church's stance on Confucian rituals.

He was recalled to Seoul and promoted in 1796 but preferred to take up a position as county magistrate at Koksan in Hwanghae Province in 1797. In 1799, he briefly withdrew to his family home but was summoned back to Seoul by the king in 1800.

2.3. Administrative and Local Governance Experience

Jeong Yagyong's experiences as a local magistrate and administrator deeply informed his practical theories on governance. As the magistrate of Koksan County, he demonstrated a strong commitment to the welfare of the populace and the integrity of public officials.

Before his appointment to Koksan, the region had experienced a tax resistance movement led by the agricultural laborer Yi Gye-shim. According to law scholar Cho Kuk, Jeong Yagyong, upon assuming office, chose not to punish Yi Gye-shim. Instead, he praised Yi's courage, stating that those who protest against official corruption should be rewarded with "a thousand pieces of gold." This act exemplified Jeong Yagyong's philosophy of "Aemin" (애민AeminKorean, lit. "love for the people"), emphasizing that officials should listen to the grievances of the common people rather than suppress them with state authority and law.

His practical administrative theories, later elaborated in his magnum opus, Mokmin Simseo (Admonitions on Governing the People), stressed the importance of local magistrates acting with unwavering integrity, fairness, and efficiency. He believed that the government's primary role was to solve the problem of poverty and ensure the equitable treatment of all citizens, particularly the most vulnerable.

3. Involvement with Catholicism and Persecution

Jeong Yagyong's life was profoundly shaped by his complex relationship with Catholicism and the intense persecutions against Christians during the Joseon Dynasty, which led to significant personal hardship and intellectual reorientation.

3.1. Early Engagement with Western Learning

Jeong Yagyong's initial interest in Catholicism and Western scientific ideas began in the 1770s, primarily through his association with a group of progressive Southern faction scholars. In 1776, through his encounters with Yi Ga-hwan and his brother-in-law Yi Seung-hun, Jeong Yagyong was introduced to the academic lineage of Seongho Yi Ik, a central figure of the Geungi school of Silhak. This connection naturally led him to interact with younger Southern scholars who were actively studying Western learning (Seohak) and Catholicism.

He participated in study groups led by Gwon Cheol-shin in 1777 and 1779 at Jueosa and Cheonjinam in Gyeonggi Province. These sessions, attended by scholars like Yi Byeok, Jeong Yak-jeon, Gwon Il-sin, Yi Ga-hwan, and Yi Gi-yang, involved discussions on Western doctrines. In April 1784, while returning to the capital after attending his eldest sister-in-law's ancestral rites, Jeong Yagyong heard about Catholic doctrine from Yi Byeok, his eldest brother Jeong Yak-hyeon's brother-in-law. Yi Byeok's explanations on the origins of creation, the soul and body, and the principles of life and death deeply captivated Jeong Yagyong, leading him to avidly read several books on Catholicism.

Later in 1784, Yi Seung-hun, who had been baptized in Beijing and became the first Korean Catholic, established a secret worship community called the "Myongnyebang Community" at the house of Kim Beom-u in Myeongdong, Seoul. Jeong Yagyong also attended these meetings. However, in early 1785, this secret gathering was discovered by the police, leading to the "Myongnyebang Incident." While Kim Beom-u, a middle-class interpreter, was imprisoned and later died in exile, Jeong Yagyong and other aristocratic participants were released. Yi Byeok died due to conflict with his father, and Yi Seung-hun apostatized under family pressure, leading to the disbandment of the community. Jeong Yagyong also temporarily renounced his faith but later secretly resumed contact with Catholics.

3.2. Impact of Persecutions

Jeong Yagyong's association with Catholicism brought him immense suffering through several major persecutions.

In October 1787, Jeong Yagyong, Yi Seung-hun, and Kang Yi-won secretly studied Catholic texts at Kim Seok-tae's house in Banchon. When this fact was revealed, it led to the "Banhoe Incident," prompting a series of memorials from anti-Catholic scholars. Although no direct punishment was meted out, the incident sparked a debate in the court about the dangers of importing and spreading Catholic literature. At this time, Catholic texts translated into Hangul were being cheaply printed and distributed, reaching even remote mountain villages in Chungcheong Province. By 1788, King Jeongjo had officially denounced Catholicism as a "heterodox doctrine" (Sagyogyo, 사교SagyogyoKorean) and issued a nationwide ban, ordering the search and destruction of all Western books. Following this, Jeong Yagyong's father commanded his children to distance themselves from Catholicism; Jeong Yagyong and Jeong Yak-jeon complied, but Jeong Yak-jong remained steadfast in his faith.

The "Shinhae Persecution" (1791), also known as the Jinshan Incident, was a pivotal moment. Yun Ji-chung, Jeong Yagyong's maternal cousin, caused a major social uproar by conducting his mother's funeral according to Catholic rites and refusing to perform traditional ancestral rituals. This act was seen as a rejection of "filial piety," a core Confucian value, and by extension, "loyalty" to the king, thus challenging the very foundation of Joseon's Confucian-based governance. Yun Ji-chung and his cousin Gwon Sang-yeon were beheaded, and Yi Seung-hun, Jeong Yagyong's brother-in-law and then a magistrate, was stripped of his office. While King Jeongjo had previously maintained a lenient policy towards Catholicism, this incident prompted him to take decisive action, ordering severe punishment and the burning of Western books in the Hongmungwan library. The incident also exacerbated political factionalism, dividing the Southerners into Gongseo (공서GongseoKorean, anti-Catholic) and Shinseo (신서ShinseoKorean, pro-Catholic) factions. Following this, Jeong Yagyong publicly severed all ties with Catholicism. However, his familial connection to Yun Ji-chung continued to make him a target for attacks from the Westerner faction. Within his family, Jeong Yak-jong also remained committed to Catholicism despite the persecution, refusing to participate in ancestral rites and moving his family to Bunwon across the Han River. Jeong Yak-jong later became the head of the Myongnyehui (明道會) in 1800 and authored Jugyo Yoji (主教要旨), a two-volume Christian doctrinal book written in Hangul, which was the first Christian text written in Korean.

In June 1795, the "Eulmyo Persecution" occurred when the Police Bureau failed to arrest Zhou Wenmo, a Chinese missionary who had secretly entered Joseon. Those arrested in connection with the incident were tortured but refused to reveal Zhou's whereabouts, dying in prison. Two months later, accusations against Yi Seung-hun, Yi Ga-hwan, and Jeong Yagyong for their alleged involvement in Zhou Wenmo's escape intensified. Under pressure from the Noron Byeokpa faction, King Jeongjo reluctantly exiled Yi Seung-hun to Yesan and demoted Yi Ga-hwan to Chungju Moksa. Jeong Yagyong was demoted seven ranks and exiled to Geumjeong Chalbang in Hongju, South Chungcheong Province. This demotion was intended to allow him to atone for his past association with Catholicism by suppressing its spread in the Chungcheong region, where its influence was growing. Jeong Yagyong's efforts in Geumjeong were effective; he successfully persuaded locals to abandon Catholicism and even apprehended Yi Jon-chang, a prominent Catholic leader in the area.

The most devastating persecution for Jeong Yagyong was the "Shinyu Persecution" of 1801. In the summer of 1800, King Jeongjo died suddenly, and the regency for the young King Sunjo fell to Queen Jeongsun, King Yeongjo's widow. Queen Jeongsun, whose family belonged to the Noron Byeokpa faction, had been marginalized during Jeongjo's reign and harbored animosity towards the Southerners and their reformist, often Catholic-leaning, agenda. On January 10, 1801, she issued a decree to suppress Catholicism, initiating a widespread purge of the Southerners. Jeong Yak-jong, Jeong Yagyong's elder brother and the head of the Catholic community, was among the first to be arrested and executed, along with Yi Seung-hun, in the spring of 1801. Jeong Yak-jong's eldest son, Jeong Cheol-sang (정철상Jeong Cheol-sangKorean), was executed a month later.

Jeong Yagyong was arrested on February 8, 1801, and subjected to severe interrogation and torture. He defended himself by asserting that his interest in Catholicism was purely academic and that he had renounced the faith after the 1791 Jinshan Incident. He even denounced Catholic leaders like Gwon Cheol-shin and Hwang Sa-yeong (황사영Hwang Sa-yeongKorean) and suggested interrogating weaker believers like slaves or students to identify Catholics. Despite his efforts, the Noron Byeokpa faction was determined to eliminate him. However, testimonies from other arrested Catholics corroborated his claims of apostasy. After 18 days of imprisonment, Jeong Yagyong and his second elder brother, Jeong Yak-jeon, were spared execution and instead exiled, Jeong Yagyong to Janggi Fortress in Pohang, Gyeongsang Province.

His exile was further prolonged by the "Hwang Sa-yeong Silk Letter Incident" of 1801. Hwang Sa-yeong (1775-1801), Jeong Yagyong's younger sister's husband, wrote a controversial letter on silk to the Bishop of Beijing. The letter detailed the persecutions in Korea and controversially requested Western nations to send warships and troops to overthrow the Joseon government, proposing that Korea be subjected to China, where Catholicism was permitted. The letter's carrier was apprehended, and its contents intensified the persecution. Although it was clear that Jeong Yagyong and Jeong Yak-jeon were not Catholic believers, the incident ensured their continued exile. They parted ways in Naju, with Jeong Yak-jeon heading to Heuksando Island and Jeong Yagyong to Gangjin, South Jeolla Province, marking the beginning of his 18-year banishment.

4. Exile and Scholarly Productivity

Jeong Yagyong's 18-year exile was a period of immense personal hardship but also one of extraordinary scholarly productivity, during which he composed his most influential works.

4.1. Life in Exile and Major Writings

Jeong Yagyong's exile began on December 28, 1801, when he arrived in Gangjin, South Jeolla Province. Penniless and friendless, he initially found shelter in the back room of a dilapidated tavern run by a widow, outside Gangjin's East Gate. He lived there until 1805, naming his room "Sauijae" (사의재SauijaeKorean, lit. "room of four obligations": clear thinking, serious appearance, quiet talking, sincere actions). During this period, he was able to utilize the extensive library of his mother's family, the Haenam Yun clan, located in nearby Haenam County, for his research and writing.

By 1805, Queen Dowager Kim had died, and the young King Sunjo had come of age, putting an end to the violent persecutions against Catholics. This allowed Jeong Yagyong more freedom of movement within the Gangjin area. In the spring of 1805, he visited Baeknyeon-sa Temple, where he met Venerable Hyejang, the newly appointed monk in charge. Their intellectual exchange quickly led to a close friendship, with Hyejang becoming a student of Jeong Yagyong, particularly in the study of the I Ching.

Later that year, Hyejang helped Jeong Yagyong move from the tavern to Boeun Sanbang, a small hermitage at the nearby Goseong-sa temple, which was under Hyejang's supervision. Finally, in the spring of 1808, he moved into a simple, thatched-roof house belonging to a distant relative of his mother, nestled on the slopes of a hill overlooking Gangjin and its bay. This site is now famously known as "Tasan Chodang" (다산초당Tasan ChodangKorean, Dasan's straw hut). The hill behind the house was locally called Tasan (다산DasanKorean, lit. "tea mountain"), which became the art name by which he is best known today. Here, he taught a close-knit community of students who lodged nearby and dedicated himself to writing, accumulating a library of over a thousand books in his study.

During his 18-year exile (1801-1818), Jeong Yagyong embarked on an incredibly prolific writing career, producing an estimated 500 volumes, or approximately 14,000 pages. These works primarily aimed to outline a comprehensive reform program for governing Joseon based on Confucian ideals. He first focused on the I Ching, completing Chuyeoksajeon (주역사전ChuyeoksajeonKorean) in 1805, followed by a reflection on the Classic of Poetry in 1809. His writings covered a vast array of subjects, including politics, ethics, economy, natural sciences, medicine, and music.

After his return from exile in 1818, he published his most important works, collectively known as "One Table, Two Books" (일표이서, 일표이서Ilpyo IseoKorean):

- Mokmin Simseo (목민심서Mokmin SimseoKorean, lit. Admonitions on Governing the People), completed in 1822, offered a blueprint for local administration and the conduct of officials.

- Gyeongse Yupyo (경세유표Gyeongse YupyoKorean, lit. A Design for Good Government), also completed in 1822, presented a comprehensive plan for national governance reform. Its original title was Bangnye Chobon (방례초본Bangnye ChobonKorean, lit. Draft for the Country's Rites), indicating his focus on ritual and social order.

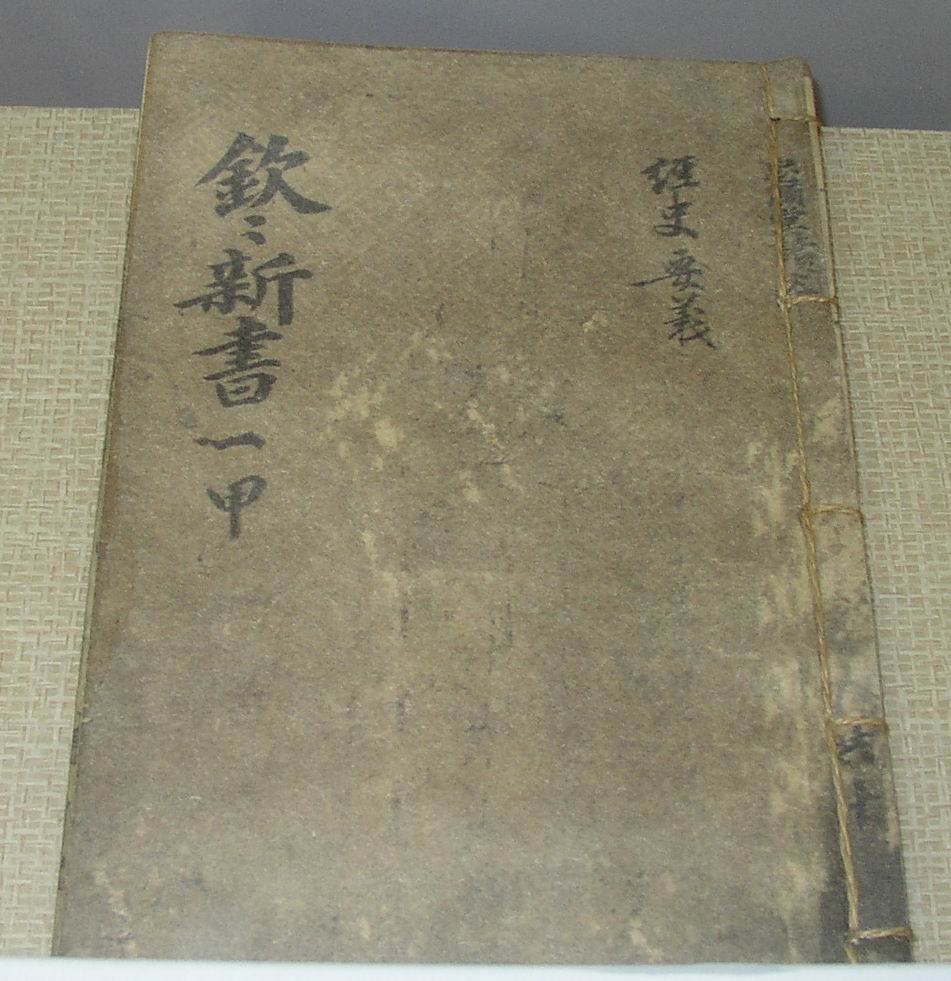

- Heumheumsinseo (흠흠신서HeumheumsinseoKorean, lit. On the Careful Administration of Justice), published in 1819, detailed reforms for the judicial system, emphasizing fairness and prudence in legal judgments.

Other significant works from his exile period and after include:

- Aeongakbi (아언각비AeongakbiKorean, 1819) on linguistics.

- Sadekoryesanbo (사대고례산보SadekoryesanboKorean, 1820) on diplomacy.

- A-bang Gangyeokgo (아방강역고A-bang GangyeokgoKorean) and Daedong Sugyeong on geography.

- Ma-gwa Hoetong (마과회통Ma-gwa HoetongKorean) on medicine.

- Jeonnon and Tangnon on administrative reform.

- Dasan-jip (다산집Dasan-jipKorean), a collection of his writings.

His prolific output during exile transformed his personal suffering into a monumental intellectual legacy, providing detailed solutions to the pressing societal problems of his time.

4.2. Tea Revival

Jeong Yagyong had been living in Gangjin for several years when Venerable Hyejang arrived from Daeheung-sa Temple to take charge of Baeknyeon-sa Temple. During those years, spent in a poor inn with very little money, Jeong Yagyong's health had suffered from the low nutritional value of his food, and he suffered from chronic digestive problems. Jeong Yagyong and Hyejang first met on the 17th day of the 4th month, 1805, not long after Hyejang's arrival. Only a few days later, Jeong Yagyong sent a poem to Hyejang requesting some tea leaves from the hill above the temple. This poem, dated in the 4th month of 1805, very soon after their meeting, makes it clear that Jeong Yagyong already knew the medicinal value of tea and implies that he knew how to prepare the leaves for drinking.

It has often been claimed that Jeong Yagyong learned about tea from Hyejang, but this and a series of other poems exchanged between them suggest that in fact Hyejang and other monks in the region learned how to make a kind of caked tea from Jeong Yagyong. This would make him the main origin of the ensuing spread of interest in tea. In 1809, Venerable Cho-ui from the same Daeheung-sa Temple came to visit Jeong Yagyong in Gangjin and spent a number of months studying with him there. It seems more than likely that Cho-ui first learned about tea from Jeong Yagyong and adopted his very specific, rather archaic way of preparing caked tea. After that, it was Venerable Cho-ui who, during his visit to Seoul in 1830, shared his tea with a number of scholars. Among them, some poems were written and shared to celebrate the newly discovered drink, in particular the Preface and Poem of Southern Tea (Namcha Byeongseo, 남차병서Namcha ByeongseoKorean) by Geumryeong Pak Yeong-bo (금령 박영보Geumryeong Pak Yeong-boKorean).

After this, Cho-ui became especially close to Chusa Kim Jeong-hui, who visited him several times, bringing him gifts of tea during his exile on Jeju Island in the 1740s. A letter about Jeong Yagyong's method of making caked tea has survived, dated 1830, that Jeong Yagyong sent to Yi Si-heon (이시헌Yi Si-heonKorean; 1803-1860), the youngest pupil taught by him during his 18 years of exile in Gangjin: "It is essential to steam the picked leaves three times and dry them three times, before grinding them very finely. Next that should be thoroughly mixed with water from a rocky spring and pounded like clay into a dense paste that is shaped into small cakes. Only then is it good to drink."

5. Intellectual and Philosophical Contributions

Jeong Yagyong's intellectual contributions represent a profound synthesis of traditional Confucian thought with innovative, practical, and reformist ideas, profoundly impacting Korean intellectual and political history.

5.1. Synthesis of Silhak and Neo-Confucianism

Jeong Yagyong is renowned for his efforts to synthesize the practical learning (Silhak) tradition with the established Neo-Confucianism of the Joseon period. He lamented the contemporary academic focus on fruitless debates over abstract theories of *li* (principle) and *qi* (material force) and the excessive emphasis on etymological scholarship. He advocated for a return to the original thought of Confucius and Mencius, which he termed "Susa learning" (Susa-hak, 수사학Susa-hakKorean), a reference to the two rivers in Confucius's homeland. This approach aimed to reform scholarship and governance towards a more practical, people-centered, and rational system.

He fundamentally challenged the prevailing Neo-Confucian doctrines, particularly those of Zhu Xi. Jeong Yagyong rejected Zhu Xi's theories of *li* and *qi*, instead reasserting Confucius and Mencius's concept of *yangqi* (nurturing vital energy) and connecting it to his philosophy of *mokmin* (governing the people). He argued that the purpose of scholarship should be re-focused on more tangible concerns such as music, ritual, and law, and that the *gwageo* (civil service examinations) should be reformed to reflect these practical areas. He also categorized the defects and corruption of Confucianism after the Han Dynasty into five types: *seongri* (nature and principle), *hungo* (exegetical studies), *munjang* (literary composition), *gwageo* (civil service examinations), and *sulsu* (divination/geomancy), advocating for a new, rational, and practical Confucianism.

In his philosophy of human nature (*in-seong-ron*), Jeong Yagyong proposed the "theory of human nature as preference" (*seonggiho-seol*, 성기호설seonggiho-seolKorean), asserting that human nature is fundamentally characterized by preferences (*giho*). He recognized the coexistence of both "moral nature" (*doui-ji-seong*, 도의지성doui-ji-seongKorean) and "animal nature" (*geumsu-ji-seong*, 금수지성geumsu-ji-seongKorean) within humans, acknowledging the inherent conflict between them. He also supported Han Won-jin's view on the difference between human and animal nature (*inmul-seongdong-ironbyeon*), while adding his unique perspective that while the nature of *qi* (material force) is the same, the inherent nature (*bonyeon-ji-seong*) differs. He rejected Zhu Xi's notion that the *qi* of human nature could be pure or turbid. He also distinguished "Heaven" (Cheon, 천CheonKorean) into visible Heaven (Yuhyeongcheon), controlling Heaven (Jujaecheon), and principle Heaven (Yeokricheon), emphasizing faith in the controlling Heaven. He viewed the Mandate of Heaven (Cheonmyeong, 천명CheonmyeongKorean) as the will of the people politically and as true destiny ethically, stressing the duty of a virtuous ruler for the people.

Jeong Yagyong also opposed the deification of sages, asserting that anyone could become a sage through sincere effort (*seong*). He emphasized not only Confucius's principles of loyalty (*chung*) and reciprocity (*seo*), and filial piety (*hyo*) and fraternal respect (*je*), but also added "benevolence" (*ja*, 자jaKorean) as an obligation of superiors towards their subordinates.

5.2. Theories of Governance and Administration

Jeong Yagyong's theories on statecraft, public administration, and the ideal conduct of officials were central to his reformist agenda, with a strong emphasis on integrity, efficiency, and the welfare of the people. His flagship work, Gyeongse Yupyo (A Design for Good Government), originally titled Bangnye Chobon (Draft for the Country's Rites), presented a comprehensive blueprint for national governance, covering institutions, local administration, land systems, labor, commerce, military, and examination systems.

He believed that the government should play a major role in alleviating poverty and ensuring social justice. In Mokmin Simseo (Admonitions on Governing the People), he stressed the critical importance of local magistrates acting with integrity and fairness, providing detailed guidelines for their conduct, emphasizing their role as servants of the people. He argued that officials should prioritize the well-being of the populace above all else, advocating for a system where public service was characterized by honesty and dedication.

5.3. Economic Reforms and Social Equity

Land reform was a critical issue for Silhak reformers, and Jeong Yagyong significantly elaborated upon the proposals of earlier scholars like Yu Hyeong-won and Seongho Yi Ik. He criticized the prevailing system where the *sadaebu* (aristocratic class) monopolized agricultural land, leading to widespread tenant farming and exploitation. At the time, *sadaebu* monopolized 100% of the farmland, and all commoners were tenant farmers. This situation continued until the Japanese colonial period, with 64% of national farmland being tenant-farmed in 1944. Jeong Yagyong estimated that in his time, a single *sadaebu* could own enough land to support 990 people, with some prominent families owning land sufficient for nearly 4,000 people, while imposing high tenant fees (up to 30% of output). The *sadaebu* also burdened tenant farmers with taxes. The population was estimated at 8 million, with 8 million *gyeols* of farmland, meaning each household needed one *gyeols* to avoid starvation.

To address this inequality, Jeong Yagyong proposed two major land reform systems:

- Jeongjeon-ron (정전론Jeongjeon-ronKorean, Well-field system): This system, envisioned during his exile, proposed dividing land into nine sections, resembling the Chinese character for "well" (井). Eight sections would be distributed to eight farming households for cultivation, while the ninth, central section would be communally farmed, with its produce used to pay taxes for the collective.

- Yeojeon-ron (여전론Yeojeon-ronKorean, Village-land system): Rather than central state ownership, Jeong Yagyong proposed a system where the village collectively owned and farmed its land. The produce would then be divided among villagers based on the amount of labor each contributed. This "socialistic" approach aimed to eliminate land inequality and ensure that farmers directly benefited from their labor, moving away from exploitative tenancy.

Beyond land reform, Jeong Yagyong advocated for a more equitable and just economic system. He proposed the principle of Sonbuikbin (손부익binSonbuikbinKorean, lit. "reducing the rich to benefit the poor"), arguing that wealth should be redistributed to alleviate poverty. He also classified socially and economically vulnerable groups into "four types of poor" (hol-abi, gwabu, goa, dokgeo-noin: widowers, widows, orphans, and the elderly living alone), along with the sick, children, and disaster victims. He urged the state and society to care for these groups, envisioning Joseon as a welfare state built on the principle of *aemin* (love for the people). These class conflicts were evident in events like the 1923 Amtae-myeon tenant dispute, where farmers protested against landlords who collected 80% of the harvest as rent. Such issues were later addressed by land reforms in both North (1946) and South (1948) Korea.

5.4. Philosophy of Ritual and Social Harmony

The philosophy of Ye (예YeKorean, ritual or rites) constitutes a significant portion of Jeong Yagyong's writings. He viewed Ye as a fundamental blueprint for good government and extended its principles to his classical studies and natural sciences. He also developed the theory of "Middle Harmony of Nature and Emotion" (Seongjeongjunghwa-ron) and "Middle Harmony of Ritual and Music" (Yeakjunghwa-ron), emphasizing the original Confucian ideal of benevolent rule.

His theory of sacrificial rites (*jesa*, 제사jesaKorean) reflected his socio-political concern for virtuous rule and righteous government. He aimed to motivate people to practice human imperatives in their daily lives and to revitalize Joseon society, which was based on the Confucian order of Ye. In Mokmin Simseo, he outlined a cognitive process for ritual practice:

1. The cognition of the ritual object leads to an intentional mental movement towards it.

2. This intentionality entails reverence (*gyeong*, 경gyeongKorean) and purification (*seong*, 성seongKorean) in the ritual process, making the practice significant through sincerity and seriousness.

Jeong Yagyong intended to regulate the excessive ritual practices of the literati and restrict popular "licentious cults" (*eumsa*, 음사eumsaKorean) that he deemed impious and overly enthusiastic. He redefined Zhu Xi's concept of "seriousness" (which contained elements of quietistic mysticism, *jeong*, 정jeongKorean) into "prudential reverence," emphasizing intentional pietism and cataphatic activism (active contemplation) rather than passive meditation. His ultimate goal was to foster social order and harmony through proper conduct and ethical governance, ensuring that rituals served their true purpose of cultivating virtue and maintaining social cohesion.

5.5. Contributions to Science and Practical Learning

Jeong Yagyong's commitment to practical learning extended significantly into scientific and engineering fields, reflecting his dedication to societal progress. His most celebrated contribution is the invention of the Geojunggi crane, which revolutionized the construction of Hwaseong Fortress. This innovation, based on principles of leverage and pulleys, drastically reduced labor and costs, showcasing his profound understanding of mechanics. He also designed a pontoon bridge for the Han River, further demonstrating his engineering prowess. He also rationally and scientifically explained the formation process of the principles of change (*Yeokri*), opposing the view of Yin-Yang and the 64 hexagrams as superstitious doctrines.

In the field of medicine, his work Ma-gwa Hoetong (마과회통Ma-gwa HoetongKorean), an advanced treatise on measles and smallpox, was based on the insights of the royal physician Yi Heon-gil. This book proved crucial in saving countless lives in Joseon until the advent of modern medicine.

His broader contributions to applied knowledge, including geography (e.g., A-bang Gangyeokgo, Daedong Sugyeong), linguistics (e.g., Aeongakbi), and administrative reform, underscored his belief that scholarship should directly address and solve real-world problems. He actively sought to integrate useful knowledge from various sources, including European and Chinese texts, to advance practical fields and improve the lives of the people.

6. Personal Life and Family

Jeong Yagyong's personal life, particularly his family relationships, was deeply intertwined with his public career and the political and religious upheavals of his time.

6.1. Marriage and Children

In 1776, at the age of 14, Jeong Yagyong married Lady Hong of the Pungsan Hong clan (1761-1839). His father-in-law, Hong Hwabo, was a respected military official who served as a Seungji (Royal Secretary) and Yeongnam Udo Byeongmajeoldosa (Provincial Military Commander). Despite his small stature, Hong Hwabo was known for his bravery and expertise in military strategy, having distinguished himself in repelling Qing Dynasty pirate ships in 1771 as Jangyeon Busasa. In 1775, he was appointed Seungji, an unusual appointment for a military official at the time. This connection to a military family likely influenced Jeong Yagyong's later writings on military affairs, such as A-bang Bi-eogo.

Jeong Yagyong and Lady Hong had ten pregnancies, resulting in six sons and three daughters. However, four sons and two daughters died prematurely, mostly due to smallpox and measles, which were rampant at the time. This high infant mortality rate caused profound grief for Jeong Yagyong and his wife. He wrote poignant letters to his surviving children, particularly after the death of his youngest son, Nong-a, from smallpox in 1802 while Jeong Yagyong was in exile. He expressed deep sorrow for not being able to be present at Nong-a's deathbed and urged his other sons, Hak-yeon and Hak-yu, to comfort their grieving mother. Nong-a's death on his birthday was particularly heartbreaking, and Jeong Yagyong had communicated with him by sending snail shells, which Nong-a eagerly awaited.

His surviving children were:

- Unnamed daughter (miscarriage in July 1781, died four days after birth)

- Son: Jeong Hak-yeon (정학연Jeong Hak-yeonKorean; 1783-1859), also known as Mu-jang (무장Mu-jangKorean) or Mu-a (무아Mu-aKorean).

- Son: Jeong Hak-yu (정학유Jeong Hak-yuKorean; 1786-1855), also known as Mun-jang (문장Mun-jangKorean) or Mun-a (문아Mun-aKorean).

- Unnamed son (1789-1791), childhood name Ku-jang (구장Ku-jangKorean) or Ku-ak (구악Ku-akKorean), died of smallpox.

- Unnamed daughter (1792-1794), childhood name Hyo-sun (효순Hyo-sunKorean) or Ho-dong (호동Ho-dongKorean), died of smallpox.

- Daughter: Lady Jeong (b. 1793).

- Unnamed son (1796-1798), childhood name Sam-dong (삼동Sam-dongKorean), died of smallpox.

- Unnamed son (1798), died shortly after birth.

- Unnamed son: Nong-a (농아Nong-aKorean; 1799-1802), died of smallpox.

During his exile in Gangjin, Jeong Yagyong also had a concubine named Namdang-ne (첩 남당네cheop Namdang-neKorean), from a seaside village, with whom he had a daughter named Hong-im (홍임Hong-imKorean).

6.2. Descendants and Family Legacy

Despite the severe political persecution and the "pejok" (폐족pejokKorean, lit. "ruined family") status imposed on his family, which prohibited his direct descendants from holding official positions, Jeong Yagyong's lineage eventually recovered. By the time of his grandsons, some of his direct descendants were able to pass civil service examinations and enter government service, thus overcoming the "pejok" status. Notable descendants include his grandson Jeong Dae-rim (1807-1895), who became a *jinsa* and served as Danyang County Magistrate, and Jeong Dae-mu (b. 1824), who served as Samcheok Busasa. His great-grandson Jeong Mun-seop (1855-1908) passed the literary civil service examination and served as Biseowonseung.

In modern times, the actor Jung Hae-in is a direct sixth-generation descendant of Jeong Yagyong, highlighting the enduring legacy of his family in Korean society.

7. Later Years and Legacy

Jeong Yagyong's life after exile was marked by continued scholarly pursuit and a lasting, though often posthumous, impact on Korean intellectual and political thought.

7.1. Post-Exile Life and Final Years

Jeong Yagyong's 18-year exile in Gangjin finally ended in May 1818, when he was allowed to return to his family home in Mahyeon-ri, near Seoul. Although he was briefly reinstated to a position as Seungji (Royal Secretary) in August of that year, further attempts to bring him back into government service were continually blocked by persistent factional politics, particularly the animosity from the Noron faction.

He spent his final years quietly at his family home, known as Yeoyudang (여유당YeoyudangKorean, lit. "house of leisure and contemplation"), near the Han River. During this period, he continued his scholarly pursuits, consolidating and refining his vast body of work. Jeong Yagyong passed away in 1836, on his sixtieth wedding anniversary, at his residence in Mahyeon-ri. His final poem, Hoi-hon-si (회혼시Hoi-hon-siKorean, lit. "poem on the sixtieth wedding anniversary"), reflected on his long life and marriage. Before his death, he reportedly advised his children to remain in Hanyang (Seoul) at all costs, emphasizing that opportunities would vanish outside the capital.

In 1910, he was posthumously promoted to Jeongheondaebu Gyujanggak Jehak and granted the posthumous title "Mundo" (문도MundoKorean).

7.2. Scholarly and Historical Assessment

Jeong Yagyong is widely regarded as the most significant figure in the Joseon Silhak movement, having synthesized and systematized its diverse strands. Scholars praise his ability to integrate practical experience, gained from his central government career under King Jeongjo and his local administrative roles, with profound academic insights developed during his exile. His extensive writings, encompassing over 500 volumes, cover a vast range of subjects from Neo-Confucianism, astronomy, and geography to mathematics and medicine. His "One Table, Two Books" - Gyeongse Yupyo, Mokmin Simseo, and Heumheumsinseo - are considered masterpieces of statecraft and social thought, characterized by their precision, breadth, clarity, and original insights.

Professor Ogawa Haruhisa of Nishogakusha University in Tokyo lauded Jeong Yagyong for his egalitarian ideas and the "precious" elements of his philosophy, formed despite his suffering, which remain relevant for contemporary scholars. Professor Peng Lin of Qinghua University in Beijing, specializing in Chinese classics, found Jeong Yagyong's study of rites "highly unique" and "astounding," noting his comprehensive approach that even many Chinese scholars could not achieve. Professor Don Baker of the University of British Columbia highlighted Jeong Yagyong's "moral pragmatism," emphasizing his ability to solve problems while upholding strong moral values, aiming for material progress that fosters a more moral society. Jeong In-bo, a prominent 20th-century Korean scholar, famously stated that "the study of Jeong Yagyong alone is the study of Joseon history, the study of Joseon's modern thought, the study of the clarity of Joseon's soul, and even the study of Joseon's rise and fall," underscoring his pivotal role in Korean intellectual history.

Jeong Yagyong also held interesting views on Japanese Confucian scholars. While acknowledging the historical threat posed by Japanese pirates and invasions, he expressed a surprisingly positive assessment of Japanese Confucian scholars like Itō Jinsai, Ogyū Sorai, and Dazai Shundai. He believed that their writings, though sometimes circuitous, demonstrated a "brilliant literary style" and that the presence of such "literature" (mun) in Japan meant it would no longer pose the same threat as "barbarians" lacking culture. He even stated that Japan's literature had far surpassed Joseon's, attributing this to Japan's direct access to good Chinese books from Jiangnan and the absence of the corrupting *gwageo* (civil service examination) system. He wrote: "Japan is now without worries. I read the writings of their so-called ancient scholars like Mr. Itō, and the interpretations of classics by Mr. Ogyū and Dazai Shun, and they are all brilliantly literary. From this, I know that Japan is now without worries. Although their arguments are sometimes circuitous, their literary excellence is extreme. Barbarians are difficult to control because they lack literature." (日本今無憂也,余讀其所謂古學先生伊藤氏爲文,及荻先生・太宰純等所論經義,皆燦然以文,由是知日本今無憂也,雖其議論間有迂曲,其文勝則已甚矣,夫夷狄之所以難禦者,以無文也。Japanese Confucian scholarsChinese) He also commented: "Generally, Japan first saw books through Baekje, and was initially very ignorant. However, since directly trading with Jiangnan and Zhejiang, they have purchased all good Chinese books, and without the burden of the *gwageo* system, their literature now far surpasses our nation's, which is quite shameful." (大抵,日本本因百濟得見書籍,始甚蒙昧,一自直通江浙之後,中國佳書,無不購去,且無科擧之累,今其文學遠超吾邦,愧甚耳。Japanese literatureChinese)

7.3. Social and Cultural Impact

Although Jeong Yagyong's radical proposals for social and economic reform were not fully implemented during his lifetime, his ideas profoundly influenced later generations of Korean thinkers and reformers. His emphasis on practical learning, social justice, and the welfare of the common people continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about governance, equity, and national development. His works provided a critical lens through which to analyze the contradictions of Joseon society and offered concrete solutions for building a more just and prosperous nation. He is also known as a poet who composed more than 2,500 poems.

His contributions to engineering, such as the Geojunggi, laid a significant foundation for modern engineering in Korea. His systematic approach to various disciplines and his commitment to applying knowledge for societal benefit set a precedent for future intellectual endeavors.

7.4. Criticisms and Debates

Despite his immense contributions, Jeong Yagyong has faced certain criticisms. Korean language education scholar Kim Seul-ong pointed out that Jeong Yagyong primarily wrote in Classical Chinese (Hanja), even in personal letters to his family, largely neglecting the use of Hangul, the Korean alphabet. This is seen as a missed opportunity for his profound ideas to reach a wider audience, particularly commoners and women, and reflects the limitations of his *sadaebu* (aristocratic) background, preventing him from fully transcending the boundaries of Neo-Confucian and Silhak thought.

Furthermore, Jeong Yagyong and his works were subjected to intense animosity from the Noron faction, who dominated Joseon politics for centuries. Even into the early 20th century, Noron-affiliated individuals maintained a deep-seated hatred for him due to his association with the Namin faction and Catholicism. As noted by Yun Chi-ho in his diary entry from July 17, 1935, Noron figures would neither read nor purchase Jeong Yagyong's books, reflecting a persistent political and ideological prejudice.

His relationships with powerful figures were complex. He was related to Hong Guk-yeong, a key advisor to King Jeongjo, through his father-in-law, Hong Hwabo, who was a great-granduncle of Hong Guk-yeong. His relationship with Sim Hwan-ji, a leader of the Noron Byeokpa faction and a fierce opponent, was particularly intricate. Despite Sim Hwan-ji's animosity towards Jeong Yagyong, he reportedly showed a degree of special treatment towards him among his brothers. Jeong Yagyong's second son, Jeong Hak-yu, married the daughter of Sim Uk, whose ancestors were related to Sim Hwan-ji's family, indicating a complex web of familial and political ties.

8. Commemoration and Heritage

Jeong Yagyong's life and work are widely remembered and honored in modern Korea, with various sites and recognitions dedicated to his legacy.

8.1. Memorial Sites and Cultural Recognition

Significant sites associated with Jeong Yagyong are preserved and celebrated. His birthplace in Mahyeon-ri, Namyangju, Gyeonggi Province, is now part of a well-maintained historical park that includes his ancestral home and the Silhak Museum, dedicated to the practical learning movement. His exile residence in Gangjin, South Jeolla Province, known as Tasan Chodang (Dasan's Straw Hut), is a prominent memorial site, attracting visitors who wish to learn about his life and prolific scholarly output during his banishment.

In 2012, Jeong Yagyong was designated a "UNESCO World Commemorative Figure" to mark the 250th anniversary of his birth. This recognition by UNESCO underscores his lasting global significance and the alignment of his ideals with the organization's values of human rights, social justice, and intellectual progress. He was honored alongside other influential figures such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Hermann Hesse in that year, highlighting his universal appeal and enduring relevance. This designation reflects modern Korea's profound respect for his contributions to philosophy, governance, and social reform.