1. Biography

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington's early life was marked by complexities regarding his parentage and a rich intellectual environment that fostered his scientific curiosity. His professional journey began with rigorous medical training and international travels, which laid the foundation for his distinguished career in neurophysiology.

1.1. Early life and education

Charles Scott Sherrington was born in Islington, London, England, on 27 November 1857. Official biographies initially stated his parents were James Norton Sherrington, a country doctor, and Anne Thurtell. However, later research revealed that James Norton Sherrington, an ironmonger and artist's colourman, had died in 1848, nearly nine years before Charles's birth. Charles and his two younger brothers, George and William, were almost certainly the illegitimate sons of Caleb Rose, a highly regarded surgeon from Ipswich, and Anne Brookes (née Thurtell), with whom she was living in Islington at the time of their births. No father was named in their baptism register, and there is no official record of their births. Anne and Caleb married in 1880, after Caleb's first wife had died.

During the 1860s, the family moved to Anglesea Road, Ipswich, reportedly because London exacerbated Caleb Rose's asthma. Caleb Rose was a notable classical scholar and archaeologist, and their home, Edgehill House, was filled with a fine collection of paintings, books, and geological specimens. Through Rose's interest in the Norwich School of Painters, Sherrington developed a deep appreciation for art. This intellectual environment, frequently visited by scholars, significantly fostered Sherrington's academic sense of wonder. Even before matriculation, he had read Johannes Müller's Elements of Physiology, a gift from Caleb Rose.

Sherrington entered Ipswich School in 1871, where he was taught by Thomas Ashe, a renowned English poet. Ashe served as an inspiration, instilling in Sherrington a love of classics and a desire to travel. Caleb Rose encouraged Sherrington to pursue medicine. Sherrington initially began his studies with the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS), passing his preliminary examination in general education in June 1875, and his Primary Examinations for Membership and Fellowship in April 1878 and 1879, respectively.

In September 1876, Sherrington enrolled at St Thomas' Hospital as a "perpetual pupil," a decision made to allow his two younger brothers to study law there before him. His medical studies at St. Thomas's Hospital were intertwined with his studies at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. At Cambridge, he chose physiology as his major, studying under Sir Michael Foster, often referred to as the "father of British physiology." Sherrington was an exceptional student, entering Cambridge as a non-collegiate student in October 1879 before joining Gonville and Caius College the following year. In June 1881, he earned a Starred first in physiology in Part I of the Natural Sciences Tripos (NST), and a First in Part II in June 1883. His tutors, Walter Holbrook Gaskell and John Newport Langley, noted his outstanding performance, with Gaskell informing him in November 1881 that he had achieved the highest marks in botany, human anatomy, and physiology, and the highest overall. Langley and Sherrington shared an interest in the relationship between anatomical structure and physiological function. Sherrington earned his Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons on 4 August 1884, and in 1885, he obtained a First Class in the Natural Science Tripos with distinction, along with his Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery (M.B.) degree from Cambridge. In 1886, he added the title of Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (L.R.C.P.).

Sherrington was also an active sportsman, playing football for his grammar school and Ipswich Town F.C., rugby for St. Thomas's, and participating in the rowing team at Oxford.

1.2. Early career and travels

Sherrington's involvement in the 7th International Medical Congress, held in London in 1881, marked the beginning of his work in neurological research. A significant controversy arose at the conference between Friedrich Goltz of Strasbourg, who argued against localized function in the cerebral cortex based on observations of dogs with brain sections removed, and David Ferrier, who maintained the existence of functional localization, citing a monkey that suffered hemiplegia after a cerebral lesion. A committee, including Langley, was formed to investigate. Sherrington, as a junior colleague to Langley, performed a histological examination of the right hemisphere of the dog. Their findings were reported in a paper in 1884, Sherrington's first publication.

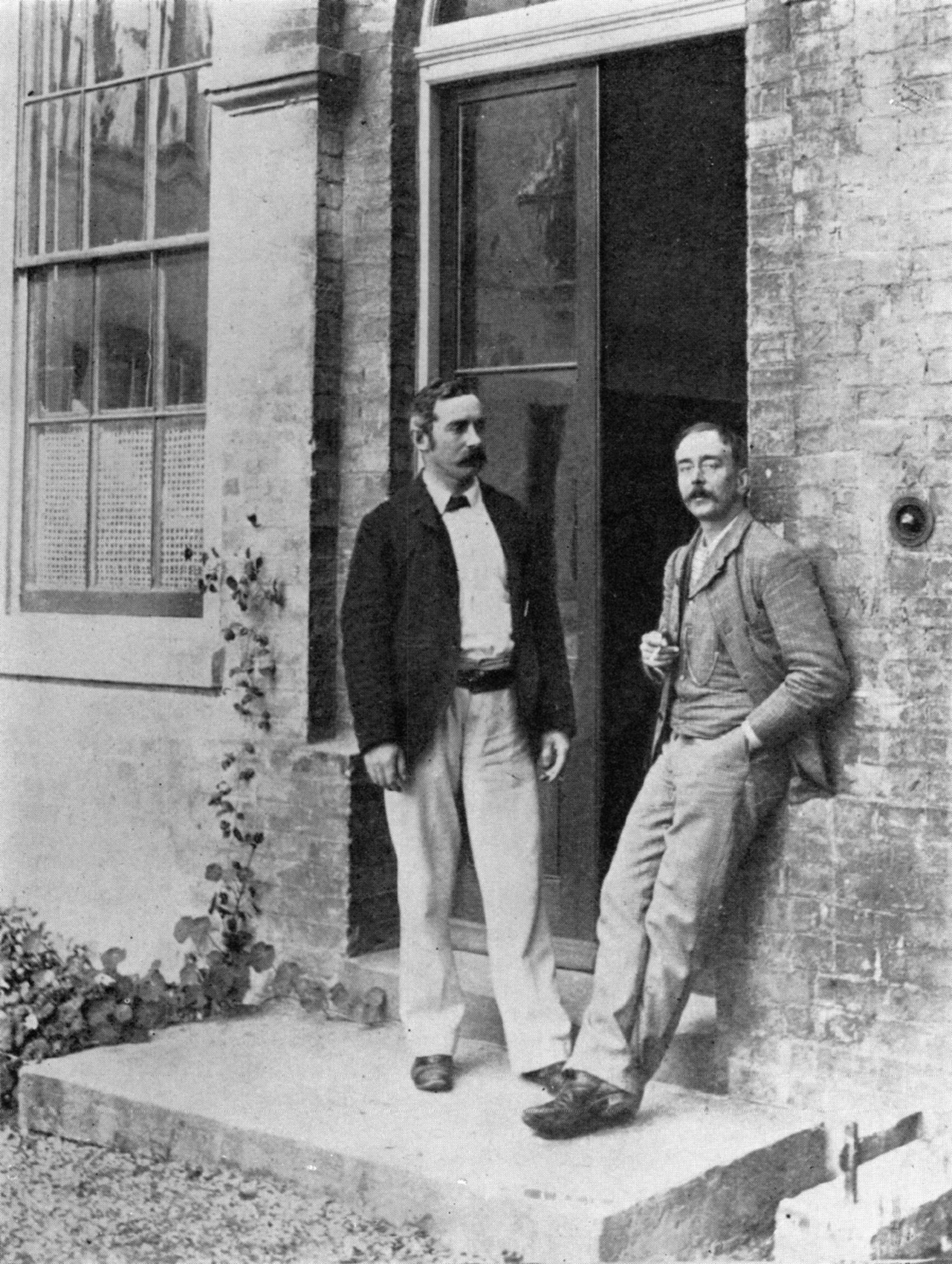

In the winter of 1884-1885, Sherrington traveled to Strasbourg to work with Goltz, who profoundly influenced him, teaching him that "in all things only the best is good enough." In 1885, a cholera outbreak in Spain led to a Spanish doctor claiming to have developed a vaccine. Under the auspices of Cambridge University, the Royal Society of London, and the Association for Research in Medicine, Sherrington, along with his friend Charles Smart Roy and J. Graham Brown, formed a group to investigate this claim in Toledo, Spain. Sherrington was skeptical of the Spanish doctor's assertion, and upon their return, the group submitted a report to the Royal Society discrediting the claim. During this trip, Sherrington did not meet Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who was in Zaragoza.

Later that year, Sherrington traveled to Berlin to meet Rudolf Virchow to inspect the cholera specimens he had collected in Spain. Virchow subsequently sent Sherrington to Robert Koch for a six-week course in technique. Sherrington ended up staying with Koch for a year, conducting research in bacteriology. His time with Virchow and Koch provided him with a strong foundation in physiology, morphology, histology, and pathology. He may have also studied with Waldeyer and Zuntz during this period. In 1886, Sherrington went to Italy to again investigate a cholera outbreak. While there, he spent considerable time in art galleries, an experience that deepened his love for rare books into an obsession.

2. Career and Professional Life

Sherrington's career was marked by a series of influential academic appointments and leadership roles within the scientific community, where he significantly advanced the fields of physiology and neuroscience.

2.1. Academic appointments

In 1891, Sherrington was appointed as the superintendent of the Brown Institute for Advanced Physiological and Pathological Research at the University of London, succeeding Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley. At the institute, he conducted research on the segmental distribution of the spinal dorsal and ventral roots, mapped the sensory dermatomes, and in 1892, discovered that muscle spindles initiated the stretch reflex. The Brown Institute provided him with ample space to work with a variety of animals, including large primates.

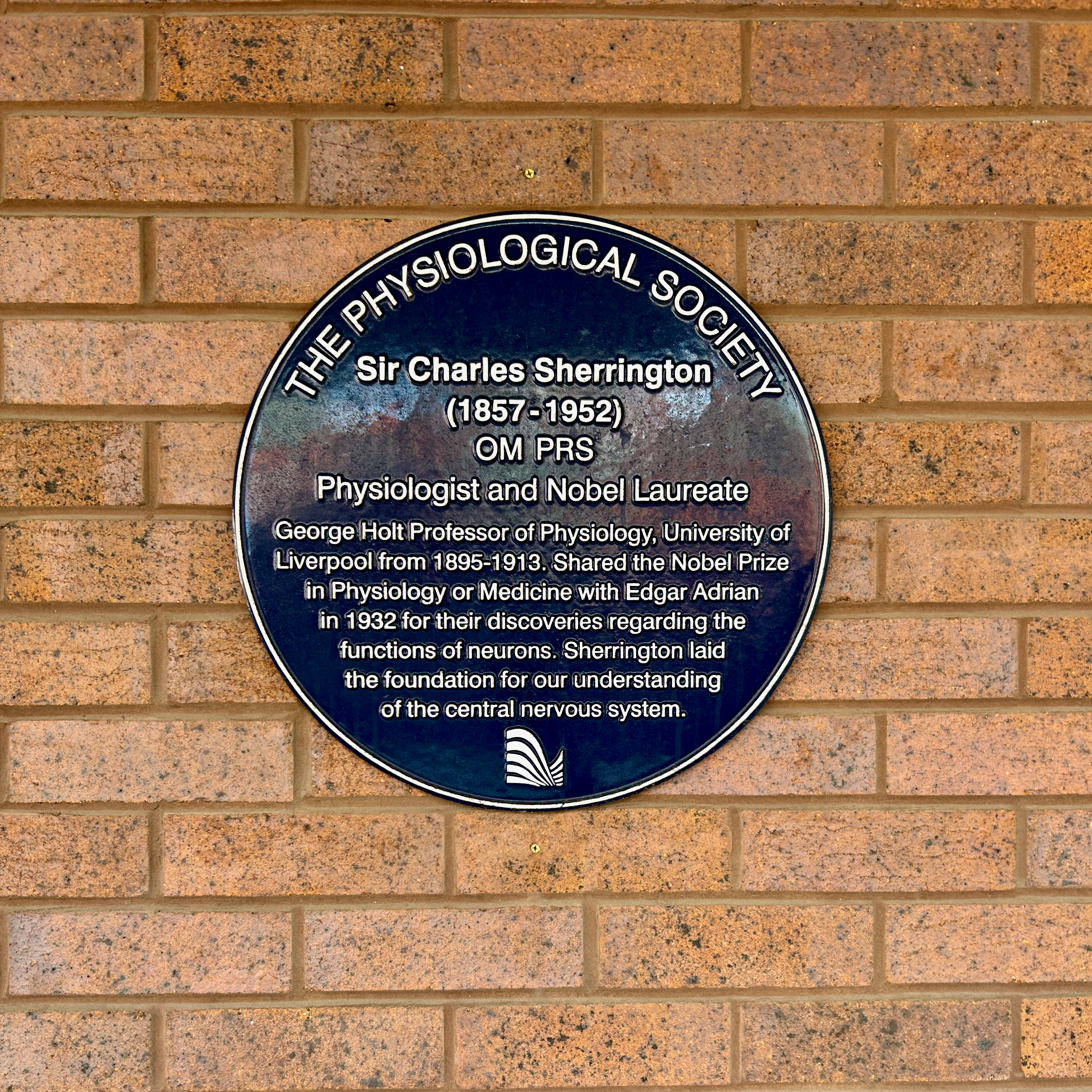

In 1895, Sherrington received his first full professorship as the Holt Professor of Physiology at the University of Liverpool, succeeding Francis Gotch. This appointment marked the end of his active work in pathology. At Liverpool, he continued his research on reflexes, working with cats, dogs, monkeys, and apes whose cerebral hemispheres had been removed. He concluded that reflexes should be viewed as integrated activities of the entire organism, rather than merely the results of isolated reflex arcs, a concept that was widely accepted at the time. He also continued his seminal work on reciprocal innervation. His papers on this subject were synthesized into the Croonian lecture of 1897. Sherrington demonstrated that muscle excitation was inversely proportional to the inhibition of an opposing group of muscles, famously stating that "desistence from action may be as truly active as is the taking of action." By 1913, he had articulated that "the process of excitation and inhibition may be viewed as polar opposites [...] the one is able to neutralize the other." His work on reciprocal innervation was a significant contribution to the understanding of the spinal cord.

Sherrington had sought employment at Oxford University as early as 1895, and in 1913, he was offered the Waynflete Chair of Physiology at Magdalen College. The electors to the chair unanimously recommended him without considering other candidates. At Oxford, Sherrington had the privilege of teaching many brilliant students, including Wilder Penfield, whom he introduced to the study of the brain. Several of his students were Rhodes scholars, and three of them-Sir John Eccles, Ragnar Granit, and Howard Florey-later became Nobel laureates. Sherrington also influenced the American pioneer brain surgeon Harvey Williams Cushing.

Sherrington's teaching philosophy at Oxford emphasized preparing students for the unknown. He stated, "After some hundreds of years of experience we think that we have learned here in Oxford how to teach what is known. But now with the undeniable upsurge of scientific research, we cannot continue to rely on the mere fact that we have learned how to teach what is known. We must learn to teach the best attitude to what is not yet known. This also may take centuries to acquire but we cannot escape this new challenge, nor do we want to."

While at Oxford, Sherrington maintained hundreds of microscope slides in a specially constructed box labeled "Sir Charles Sherrington's Histology Demonstration Slides." This collection included not only histology demonstration slides but also slides potentially related to original breakthroughs, such as cortical localization in the brain. It also contained slides from contemporaries like Angelo Ruffini and Gustav Fritsch, and from colleagues at Oxford, including John Burdon-Sanderson (the first Waynflete Chair of Physiology) and Derek Denny-Brown, who worked with Sherrington from 1924 to 1928.

Sherrington's teaching at Oxford was interrupted by World War I, which left his classes with only nine students. During the war, he contributed to the war effort by working in a shell factory, where he also studied general industrial fatigue. His work hours were demanding, from 7:30 AM to 8:30 PM on weekdays and 7:30 AM to 6:00 PM on weekends. In March 1916, he actively advocated for the admission of women to the medical school at Oxford. He resided at 9 Chadlington Road in north Oxford from 1916 to 1934, and an Oxfordshire blue plaque was unveiled in his honor at this house on 28 April 2022.

Charles Sherrington retired from Oxford in 1936. He then moved to his boyhood town of Ipswich, where he built a house. In Ipswich, he maintained extensive correspondence with former pupils and colleagues worldwide. He also continued to pursue his poetic, historical, and philosophical interests. From 1944 until his death, he served as President of the Ipswich Museum, having previously been a committee member. Although his mental faculties remained sharp until his sudden death from heart failure at age 94, his physical health declined in old age, with arthritis becoming a significant burden. He described his condition by saying, "old age isn't pleasant[,] one can't do things for oneself." Due to his arthritis, Sherrington resided in a nursing home in 1951, the year before his passing.

2.2. Royal Society presidency and fellowship

Sherrington was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1893, a significant recognition of his early scientific achievements. His leadership within the scientific community culminated in his election as President of the Royal Society, a prestigious position he held from 1920 to 1925. During this period, he also served as President of the British Association for the year 1922-1923, further solidifying his influence and standing in the scientific world.

3. Scientific Contributions

Sherrington's scientific contributions were foundational to the understanding of the nervous system, particularly his work on neural communication and the mechanisms of reflexes.

3.1. Neuroscience and the Synapse

Sherrington's experimental research established many aspects of contemporary neuroscience. His work contributed significantly to the neuron doctrine, which posits that the nervous system is composed of individual cells called neurons that communicate with each other. He conceptualized the spinal reflex as a complex system involving interconnected neurons, rather than simple isolated arcs.

Crucially, Sherrington coined the word "synapse" in 1897 to define the specialized connection between two neurons, a term suggested to him by the classicist A. W. Verrall. He meticulously described how signal transmission between neurons could be either potentiated (strengthened) or depotentiated (weakened), laying the groundwork for understanding neural plasticity. His concept of the "integrative action of the nervous system" emphasized that the nervous system coordinates various parts of the body, and that reflexes are the simplest expressions of this interactive action, enabling the entire body to function toward a definite, purposeful goal. His work effectively resolved the ongoing debate between the neuron theory and the reticular theory in mammals, thereby profoundly shaping the understanding of the central nervous system.

3.2. Reflexes and Neural Control

Sherrington's research extensively explored the nature and mechanisms of reflexes. He demonstrated that reflexes are not isolated events but integrated activities of the total organism, serving a specific purpose. He established the nature of postural reflexes and their dependence on the anti-gravity stretch reflex. He also traced the afferent stimulus (sensory input) to the proprioceptive end organs, which he had previously shown to be sensory in nature. The term "proprioceptive" itself was another concept he introduced.

A cornerstone of his work was the elucidation of reciprocal innervation, often referred to as Sherrington's Second Law. He showed that when the contraction of one muscle is stimulated, there is a simultaneous and corresponding inhibition of its antagonistic muscle. This reciprocal relationship ensures efficient and coordinated movement. He articulated that muscle excitation was inversely proportional to the inhibition of an opposing group of muscles, stating that "desistence from action may be as truly active as is the taking of action," and that "the process of excitation and inhibition may be viewed as polar opposites [...] the one is able to neutralize the other." This understanding of excitation and inhibition as complementary processes was a notable contribution to the knowledge of the spinal cord and the broader neural control of movement.

4. Major Publications

Sherrington authored several influential works that synthesized his scientific discoveries and explored his philosophical insights, leaving a lasting impact on both science and thought.

4.1. The Integrative Action of the Nervous System

Published in 1906, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System is considered Sherrington's seminal work. This book was a comprehensive compendium of ten of his Silliman lectures, which he delivered at Yale University in 1904. In this pivotal publication, Sherrington discussed the neuron theory, elaborated on the concept of the "synapse" (a term he had introduced in 1897), detailed the mechanisms of communication between neurons, and explained the function of the reflex-arc. The work effectively resolved the prevailing debate between the neuron and reticular theory in mammals, providing a coherent framework that shaped the modern understanding of the central nervous system. He theorized that the nervous system coordinates various parts of the body, and that reflexes are the simplest expressions of this interactive action, enabling the entire body to function toward a definite purpose. Sherrington emphasized that reflexes must be goal-directive and purposive. Furthermore, he established the nature of postural reflexes and their dependence on the anti-gravity stretch reflex, tracing the afferent stimulus to the proprioceptive end organs, a term he had also coined. The book was dedicated to his mentor, David Ferrier.

4.2. Man on His Nature

Man on His Nature, published in 1940 with a revised edition in 1951, represents a profound reflection on Sherrington's philosophical thought. Sherrington had extensively studied the 16th-century French physician Jean Fernel, becoming so familiar with his work that he considered Fernel a friend across centuries. This deep engagement with Fernel and his era formed the basis of Sherrington's Gifford lectures, which he delivered at the University of Edinburgh during the academic year 1937-1938. The book delves into philosophical ideas about the human mind, existence, and the nature of life, aligning with principles of natural theology. In its original edition, each of the twelve chapters begins with one of the twelve zodiac signs, reflecting Sherrington's discussion of astrology during Fernel's time in Chapter 2. In his ideas on mind and cognition, Sherrington introduced the concept that neurons work collectively in a "million-fold democracy" to produce outcomes, rather than being controlled by a central authority.

4.3. Other notable works

Sherrington's intellectual pursuits extended beyond his core scientific research, as evidenced by his other significant publications. His textbook, Mammalian Physiology: a Course of Practical Exercises, was published in 1919, immediately after his return to Oxford and the conclusion of World War I. This work provided practical guidance for physiological studies.

In 1925, he released The Assaying of Brabantius and other Verse, his first major collection of poetry, which included previously published war-time poems. Sherrington's poetic side was notably inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. While he admired Goethe as a poet, Sherrington was less enthusiastic about Goethe's scientific writings, stating that "to appraise them is not a congenial task."

Other works include The Reflex Activity of the Spinal Cord (1932) and The Brain and Its Mechanism (1933), which further elaborated on his neurophysiological insights.

5. Honours and Awards

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington received numerous prestigious recognitions and accolades throughout his distinguished career, reflecting the profound impact of his scientific contributions worldwide.

5.1. Fellowship of the Royal Society and Medals

Sherrington was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1893, an early and significant acknowledgment of his scientific prowess. His contributions were further honored with several esteemed medals:

- 1899: Baly Gold Medal of the Royal College of Physicians of London

- 1905: Royal Medal of the Royal Society of London

- 1922: Knight Grand Cross of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (GBE)

- 1924: Order of Merit (OM)

- 1927: Copley Medal

He also served as President of the British Association for the year 1922-1923.

5.2. Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The pinnacle of Sherrington's scientific recognition came in 1932 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He shared this prestigious honor with Edgar Adrian for their groundbreaking discoveries regarding the functions of neurons. Sherrington's specific contributions recognized by the Nobel Committee included his work on the localization of function in the cerebral cortex, his extensive research in reflexology, and his demonstration that reflexes require integrated neural activation, particularly highlighting the concept of reciprocal innervation of muscles. His work proved that reflexes are a collaborative process involving multiple neurons, explaining how neural current transmission is organized to facilitate efficient muscle contraction and relaxation.

5.3. Honorary Degrees

By the time of his death, Sherrington had received honoris causa Doctorates from twenty-two universities across the globe, underscoring his international acclaim and broad influence. These institutions included:

- Oxford

- Paris

- Manchester

- Strasbourg

- Louvain

- Uppsala

- Lyon

- Budapest

- Athens

- London

- Toronto

- Harvard

- Dublin

- Edinburgh

- Montreal

- Liverpool

- Brussels

- Sheffield

- Bern

- Birmingham

- Glasgow

- Wales

6. Personal Life

Sherrington's personal life provided a supportive backdrop to his intense scientific and intellectual pursuits.

6.1. Family

On 27 August 1891, Charles Scott Sherrington married Ethel Mary Wright, the daughter of John Ely Wright of Preston Manor, Suffolk, England. Ethel Mary Sherrington passed away in 1933. The couple had one child, a son named Charles ("Carr") E.R. Sherrington, who was born in 1897. During their years at Oxford, the Sherringtons frequently hosted a large group of friends and acquaintances at their home on weekends, fostering an enjoyable and intellectually stimulating social environment.

7. Death

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington's long and impactful life concluded in his nineties, marked by a decline in physical health despite his enduring mental clarity.

7.1. Details of death

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington died on 4 March 1952, in Eastbourne, Sussex, England, at the age of 94. His death was caused by sudden heart failure. While his mental faculties remained remarkably clear until the very end of his life, his bodily health suffered significantly in old age, particularly due to severe arthritis. This condition became a major burden, leading him to reside in a nursing home in 1951, the year before his passing. Speaking of his physical state, Sherrington once remarked, "old age isn't pleasant[,] one can't do things for oneself."

8. Legacy and Evaluation

Sherrington's work left an indelible mark on neuroscience, fundamentally changing the understanding of the nervous system and giving rise to numerous enduring scientific concepts and eponyms.

8.1. Impact on Neuroscience

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington's experimental research established many foundational aspects of contemporary neuroscience. His meticulous investigations into the spinal reflex, the neuron doctrine, and the concept of the synapse provided a coherent framework for understanding how the nervous system functions. His seminal publication, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System, effectively resolved the debate between the neuron and reticular theories, solidifying the cellular basis of neural communication. His discoveries fundamentally advanced the understanding of the nervous system and profoundly influenced subsequent generations of neuroscientists and medical researchers. He is widely regarded as a pioneer of modern neurophysiology, and his mentorship had a lasting impact on numerous students and colleagues, including future Nobel laureates such as John Carew Eccles, Ragnar Granit, and Howard Florey, as well as prominent figures like Wilder Penfield, John Farquhar Fulton, Alfred Fröhlich, E. M. Tansey, and Archibald Vivian Hill.

8.2. Eponyms and Scientific Concepts

Sherrington's profound contributions are immortalized in several scientific terms, reflexes, and laws named in his honour, which remain fundamental to the field of neuroscience:

- Liddell-Sherrington reflex: Associated with Edward George Tandy Liddell and Charles Scott Sherrington, this describes the tonic contraction of a muscle in response to its being stretched. When a muscle lengthens beyond a certain point, the myotatic reflex causes it to tighten and attempt to shorten, felt as tension during stretching exercises.

- Schiff-Sherrington reflex: Named after Moritz Schiff and Charles Scott Sherrington, this describes a grave sign observed in animals: rigid extension of the forelimbs after damage to the spine. It may also be accompanied by paradoxical respiration, where the intercostal muscles are paralyzed, and the chest is passively drawn in and out by the diaphragm.

- Sherrington's First Law: States that every posterior spinal nerve root supplies a particular area of the skin, with a certain overlap of adjacent dermatomes.

- Sherrington's Second Law: Also known as the law of reciprocal innervation. This fundamental principle states that when the contraction of a muscle is stimulated, there is a simultaneous inhibition of its antagonist (opposing muscle). This mechanism is essential for coordinated movement.

- Vulpian-Heidenhain-Sherrington phenomenon: Associated with Rudolf Peter Heinrich Heidenhain, Edmé Félix Alfred Vulpian, and Charles Scott Sherrington. It describes the slow contraction of denervated skeletal muscle through the stimulation of autonomic cholinergic fibers that innervate its blood vessels.

- Synapse: A term coined by Sherrington himself in 1897 to describe the junction between two neurons.

- Proprioceptive: Another term coined by Sherrington, referring to the sensory input from the body's position and movement.