1. Overview

Caspar Friedrich Wolff (Caspar Friedrich WolffGerman) was a pioneering German physiologist and embryologist widely recognized as a founder of modern embryology. His most significant contribution was the revival and vigorous defense of the theory of epigenesis, which posits that an organism develops gradually from undifferentiated material through successive stages of formation. This groundbreaking idea directly challenged the prevailing scientific dogma of his time, the preformation theory, which held that organisms were already fully formed, albeit minutely, within the seed or sperm. Wolff's meticulous observations, particularly of chick embryos, provided empirical evidence that laid the foundation for understanding how complex biological structures emerge progressively, profoundly influencing the future direction of developmental biology.

2. Life

Caspar Friedrich Wolff's life was marked by dedicated scientific inquiry and significant challenges, culminating in his influential work that reshaped the understanding of biological development.

2.1. Birth and Early Life

Wolff was born on January 18, 1733, in Berlin, then part of the Margraviate of Brandenburg. He was the son of Johann Wolff, a tailor who had relocated to Berlin in the late 17th or early 18th century, and Anna Sofia Stiebeler. His early life in Berlin laid the foundation for his later academic pursuits.

2.2. Education

Wolff embarked on his academic journey by studying medicine at the Medical-Surgical College in Berlin from 1753 to 1754. He then continued his studies at the University of Halle, enrolling in 1755. In 1759, he earned his M.D. from the University of Halle, submitting his seminal dissertation titled "Theoria Generationis" (Theory of Generation). This work was pivotal, as it revived and supported the theory of epigenesis, a concept previously proposed by ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and English physician William Harvey.

2.3. Early Career and Challenges

Following his graduation, Wolff's career faced immediate challenges. During the Seven Years' War, which began in 1756, he was compelled to serve as a field doctor in the Prussian Army starting in 1761. During this period, he also taught anatomy at the Military Hospital in Breslau. After returning to Berlin in 1763, Wolff attempted to secure permission to lecture at the Medical-Surgical College in 1762 and 1764, but he encountered strong opposition from established professors there. Consequently, he resorted to giving private lectures on anatomy, physiology, and medicine. His views, particularly his support for epigenesis, were not well received by the scientific establishment of the time. Albrecht von Haller, a prominent and influential physiologist, emerged as a powerful antagonist to Wolff's ideas, contributing to the difficulties Wolff faced in establishing a stable academic career.

2.4. Work in Russia

Despite the initial resistance to his theories, Wolff's intellectual prowess eventually gained recognition. In 1766, he received an invitation from the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences (now the Russian Academy of Sciences) to join its anatomy department. He accepted the offer and, in May 1767, traveled to Russia with his wife. With the crucial assistance of the renowned mathematician Leonhard Euler, Wolff secured the chairmanship of anatomy at the Academy in 1767. Over the next twenty-seven years, he dedicated himself to research and publishing, contributing thirty-one memoirs to the Academy's Proceedings. These included anatomical studies on the heart muscle and connective tissue. He also developed a particular interest in studying human monstrosities, collecting specimens for the Academy's anatomical cabinet. Wolff began a significant project on a "theory of monsters," intending to systematize his epigenetic ideas, but his sudden death from a cerebral hemorrhage on February 22, 1794, in Saint Petersburg, prevented him from completing this ambitious work.

3. Scientific Contributions and Research

Wolff's research spanned embryology, anatomy, and botany, but his most profound impact was in the field of embryology, where his empirical observations and theoretical insights laid the groundwork for modern understanding of development.

3.1. Epigenesis Theory

Wolff's pivotal contribution was his revival and empirical defense of the theory of epigenesis, directly challenging the then-dominant preformation theory. Preformationism held that all organs and structures of an organism were pre-existing in miniature within the gamete (e.g., a homunculus in the sperm), merely unfolding or growing during development. In contrast, Wolff's "Theoria Generationis" (1759) argued that organs are not pre-formed but rather develop gradually and progressively from undifferentiated material. He posited that cells differentiate into distinct layers, which then form the various organs. His detailed observations, particularly of chick embryos, provided compelling evidence that he could actually follow the successive stages of organ formation, demonstrating that they make their appearance gradually rather than simply enlarging from a pre-existing form. Initially, his views were met with strong opposition, notably from Albrecht von Haller, who championed preformationism.

3.2. Major Works and Theories

Wolff's theoretical contributions were primarily articulated in two major works:

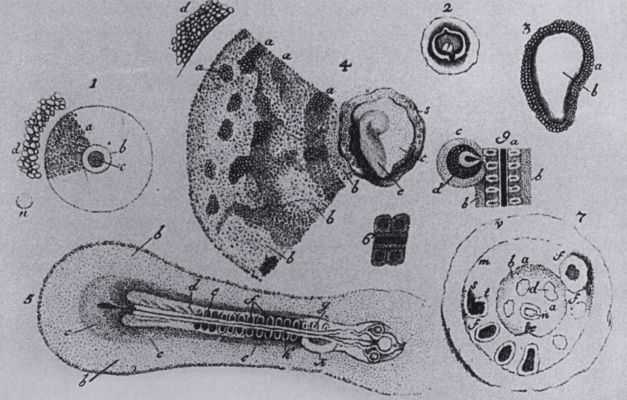

- "Theoria Generationis" (Theory of Generation), 1759: This was Wolff's doctoral dissertation, divided into three main parts: the development of plants, the development of animals, and theoretical considerations. In this work, he described how organs are formed in differentiated layers from undifferentiated cells, laying the conceptual groundwork for epigenesis.

- "De Formatione Intestinorum" (On the Formation of the Intestines), 1768-1769: This is considered Wolff's most significant work in embryology. In it, he presented detailed observations on the development of the intestine in chick embryos. Karl Ernst von Baer later praised this work as "the greatest masterpiece of scientific observation which we possess." Scientific historian William A. Locy noted that while Wolff's investigations for "Theoria Generationis" did not reach the level of Marcello Malpighi's, those presented in the 1768 paper surpassed them, holding the position of the best piece of embryological work until the contributions of Heinz Christian Pander and von Baer.

Wolff's theoretical framework also included the concept of a "vis essentialis corporis" (essential force of the body). Since he assumed a complete lack of organization at the very beginning of development, he proposed that a "hyperphysical agent" or "essential force" acted upon the egg, miraculously guiding it from a state of total disorganization to a highly organized product. He also began a major work on a "theory of monsters," aiming to systematize his epigenetic ideas regarding human malformations, though this project remained unfinished at his death.

3.3. Discovery of Wolffian Bodies and Ducts

A significant anatomical discovery attributed to Wolff is that of the primitive kidneys, known as the mesonephros (or "Wolffian bodies"), and their associated excretory ducts. He meticulously described these structures in his dissertation "Theoria Generationis," based on his detailed observations during his studies on chick embryos. This discovery was a crucial step in understanding the development of the vertebrate kidney and reproductive system.

3.4. Precursor to Germ Layer Theory

Wolff's work in "De Formatione Intestinorum" is particularly notable for foreshadowing the concept of germ layers in the embryo, a fundamental idea in modern structural embryology. In this influential paper, he demonstrated that the material from which the embryo is constructed is, in an early stage of development, arranged in the form of leaf-like layers. This insight laid a crucial foundation for the later development of the germ layer theory by scientists like Heinz Christian Pander and Karl Ernst von Baer, who further elaborated on these embryonic layers. William A. Locy recognized Wolff as the foremost investigator in embryology prior to von Baer.

4. Eponyms

Several anatomical structures and concepts are named after Caspar Friedrich Wolff in recognition of his pioneering discoveries and contributions to embryology and anatomy:

- Wolffian ducts or mesonephric ducts: These are paired embryonic structures that are precursors to male reproductive organs and parts of the kidney in vertebrates.

- Wolffian cysts: These are remnants of the Wolffian ducts that can persist in adults.

- Wolffian body or mesonephros: Refers to the primitive kidney that develops in the embryos of higher vertebrates and functions as the primary excretory organ in many lower vertebrates.

- Wolff's islands or blood islands: These are aggregates of mesodermal cells that give rise to blood cells and blood vessels during early embryonic development, particularly in the yolk sac.

5. Reception and Legacy

The reception of Wolff's theories was initially mixed, but his profound insights eventually gained widespread acceptance, cementing his status as a foundational figure in developmental biology.

5.1. Initial Reception and Criticism

Wolff's ideas, particularly his theory of epigenesis, faced considerable resistance from his contemporaries. The scientific community at the time was largely dominated by the preformation theory, which held that organisms were pre-formed in miniature within the egg or sperm. Wolff's assertion that organs developed gradually from undifferentiated material was seen as a radical departure from this established view. Albrecht von Haller, a highly influential physiologist, was one of the most powerful and vocal antagonists of Wolff's work, actively criticizing his epigenetic concepts. This strong opposition contributed to the difficulties Wolff experienced in securing academic positions and gaining immediate recognition for his groundbreaking research.

5.2. Later Recognition and Impact

Despite the initial skepticism, Wolff's meticulous empirical observations and logical arguments eventually led to the acceptance and appreciation of his work. His "De Formatione Intestinorum" was recognized as a masterpiece of scientific observation, and its detailed account of embryonic development provided irrefutable evidence against preformationism. The true significance of Wolff's epigenesis theory began to be widely acknowledged in the early 19th century. In 1821, Johann Friedrich Meckel recognized the profound importance of Wolff's work and commissioned Karl Ernst von Baer to translate it into German, making it more accessible to the scientific community.

Wolff's work, especially his foreshadowing of the germ layer concept, became foundational for later developments in embryology. Scientists like Heinz Christian Pander and Karl Ernst von Baer built upon Wolff's insights, establishing the germ layer theory as the fundamental conception in structural embryology. Consequently, Caspar Friedrich Wolff is now widely regarded as one of the most important pioneers of modern embryology, whose empirical approach and theoretical contributions irrevocably shifted the understanding of biological development from preformation to epigenesis.

6. Bibliography

Caspar Friedrich Wolff authored several influential works throughout his career, contributing significantly to the fields of embryology, anatomy, and botany. His major published works include:

- Theoria generationis, Halle, 1759 (German translation: Ostwalds Klassiker der exakten Wissenschaften Band 84/85, Leipzig 1896, reprint 1999)

- Theorie von der Generation, in zwei Abhandlungen erklärt und bewiesen (Theory of Generation, Explained and Proven in Two Treatises), Berlin, 1764

- De formatione intestinorum (On the Formation of the Intestines), Saint Petersburg, 1769

- De leone observationes anatomicae (Anatomical Observations on the Lion), Saint Petersburg, 1771

- Von der eigentümlichen und wesentlichen Kraft der vegetablischen sowohl, als auch der animalischen Substanz, als Erläuterung zu zwo Preisschriften über die Nutritionskraft (On the Peculiar and Essential Force of Both Vegetable and Animal Substance, as an Explanation for Two Prize Essays on the Nutritional Force), Saint Petersburg, 1789

- Explicatio tabularum anatomicarum VII, VIII et IX (Explanation of Anatomical Tables VII, VIII and IX), Saint Petersburg, 1801

- Über die Bildung des Darmkanals in bebrüteten Hühnchen (On the Formation of the Intestinal Canal in Incubated Chickens), Halle, 1812