1. Overview

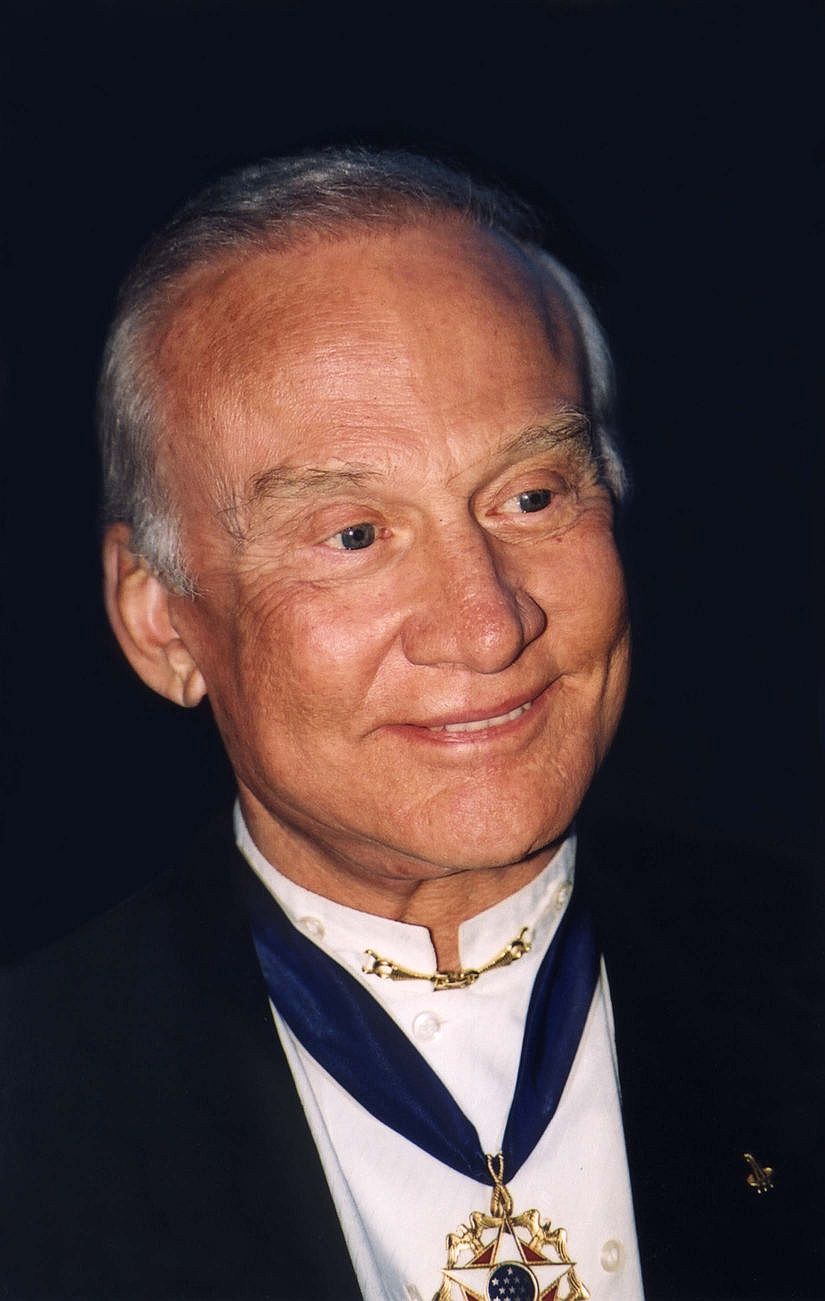

Buzz Aldrin, born Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. on January 20, 1930, is an American former astronaut, engineer, and fighter pilot renowned for his pivotal role in human space exploration. He distinguished himself as a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point and a jet fighter pilot during the Korean War, where he flew 66 combat missions and achieved two aerial victories. Aldrin became the first astronaut with a doctoral degree, earning a Doctor of Science in astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which led to his nickname "Dr. Rendezvous" due to his expertise in orbital mechanics. His contributions to the Gemini program included pioneering extravehicular activities (EVAs) on Gemini 12. Most famously, as the Lunar Module Pilot for the 1969 Apollo 11 mission, he became the second person to walk on the Moon, following Neil Armstrong. On the lunar surface, Aldrin performed the first religious ceremony in space, privately taking communion. Following his NASA career, Aldrin faced personal struggles with clinical depression and alcoholism, which he openly addressed in his autobiographies, contributing to mental health awareness. Despite these challenges, he has remained a tireless advocate for space exploration, championing concepts like the Aldrin cycler for Mars travel and envisioning humanity as a multi-planetary species. His enduring legacy extends to popular culture, notably inspiring the character Buzz Lightyear, and he has been honored with numerous accolades, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom. As of 2021, he is the last surviving crew member of the Apollo 11 mission.

2. Early Life and Education

Aldrin's early life was shaped by his family background and his academic pursuits, which laid the foundation for his distinguished military and space careers.

2.1. Birth and Family

Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. was born on January 20, 1930, at Mountainside Hospital in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. His parents, Edwin Eugene Aldrin Sr. and Marion Aldrin (née Moon), resided in the neighboring town of Montclair, New Jersey. Aldrin's father was an Army aviator during World War I and served as the assistant commandant of the Army's test pilot school at McCook Field, Ohio, from 1919 to 1922. He later left the Army in 1928 to become an executive at Standard Oil. Aldrin had two older sisters: Madeleine, who was four years his senior, and Fay Ann, who was one and a half years older. His distinctive nickname, "Buzz," which he legally adopted as his first name in 1988, originated from Fay Ann's childhood mispronunciation of "brother" as "buzzer," which was then shortened to "Buzz." As a youth, he was a Boy Scout and achieved the rank of Tenderfoot Scout.

2.2. Education

Aldrin demonstrated strong academic abilities throughout his schooling, consistently maintaining an A average. He was also an accomplished athlete, playing football and serving as the starting center for Montclair High School's undefeated state champion team in 1946. His father initially intended for him to attend the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and enrolled him at the nearby Severn School, a preparatory institution for Annapolis. His father even secured him a Naval Academy appointment from Albert W. Hawkes, a United States senator from New Jersey.

However, Aldrin had different aspirations for his future career. He suffered from seasickness and viewed ships as a distraction from his passion for flying airplanes. He confronted his father and successfully persuaded him to change the nomination to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Aldrin entered West Point in 1947, where he continued to excel academically, finishing first in his class during his plebe (first) year. He was also an excellent athlete, competing in pole vault for the academy's track and field team. In 1950, he participated in a group trip with West Point cadets to Japan and the Philippines to study the military government policies of Douglas MacArthur. The Korean War broke out during this trip. On June 5, 1951, Aldrin graduated third in his class with a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering.

3. Military Career

Aldrin's military career was marked by his service as a fighter pilot during the Korean War and his subsequent advanced studies that prepared him for spaceflight.

3.1. Korean War Service

As one of the top graduates in his class, Aldrin had the privilege of choosing his assignments. He opted for the United States Air Force, which had become a separate service in 1947 while he was still at West Point. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and underwent basic flight training in T-6 Texans at Bartow Air Base in Florida. During this period, he befriended his classmate Sam Johnson, who would later become a prisoner of war in Vietnam. Aldrin experienced a near-fatal incident when he attempted a double Immelmann turn in a T-28 Trojan, suffering a grayout but recovering in time to pull out at about 2.00 K ft, averting a crash.

Despite his father's advice to choose bombers for leadership opportunities, Aldrin chose to fly fighters. He moved to Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, where he trained on the F-80 Shooting Star and the F-86 Sabre, preferring the latter. In December 1952, Aldrin was assigned to the 16th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, part of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing, which was based at Suwon Air Base, about 20 mile south of Seoul, and actively engaged in combat operations during the Korean War. During an acclimatization flight, his main fuel system froze at 100-percent power, leading to a critical fuel shortage. He managed to manually override the setting, but this prevented him from using his radio, forcing him to return under enforced radio silence. He successfully completed 66 combat missions in F-86 Sabres in Korea and shot down two MiG-15 aircraft.

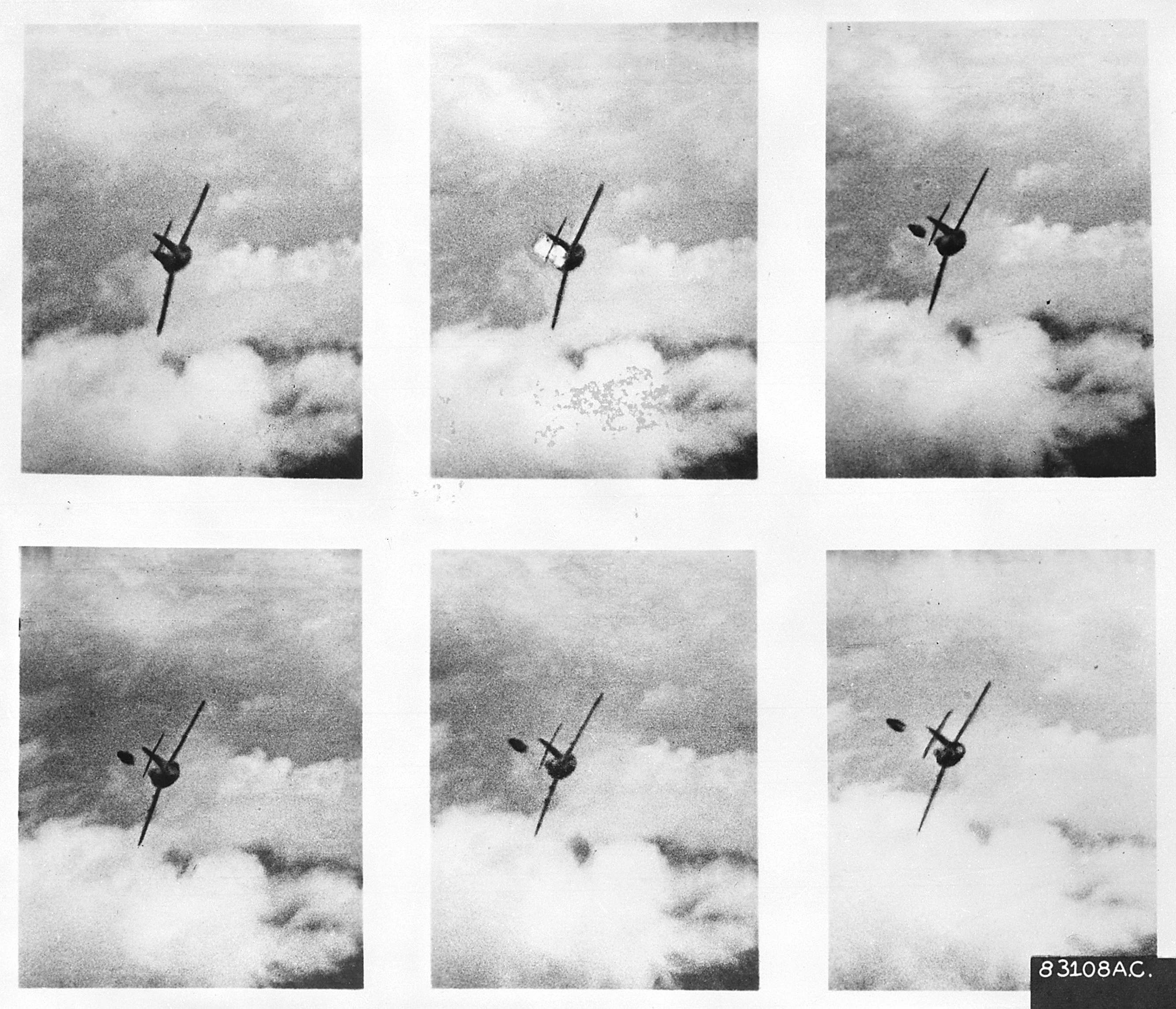

His first MiG-15 kill occurred on May 14, 1953, when he was flying about 5 mile south of the Yalu River and spotted two MiG-15 fighters below him. Aldrin opened fire on one of the MiGs, whose pilot may not have seen him. Gun camera footage taken by Aldrin, showing the pilot ejecting from his damaged aircraft, was featured in the June 8, 1953, issue of Life magazine. His second aerial victory came on June 4, 1953, while accompanying aircraft from the 39th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron on an attack on an airbase in North Korea. After a series of scissor maneuvers with an approaching MiG, Aldrin managed to get behind his opponent and fire, despite his gun sight jamming. He saw the MiG's canopy open and the pilot eject. For his service in Korea, Aldrin was awarded two Distinguished Flying Crosses and three Air Medals.

3.2. Post-War Service and MIT Doctorate

Aldrin's year-long tour in Korea concluded in December 1953, by which time the fighting had ceased. He was then assigned as an aerial gunnery instructor at Nellis Air Force Base. In December 1954, he became an aide-de-camp to Brigadier General Don Z. Zimmerman, the Dean of Faculty at the nascent United States Air Force Academy, which opened in 1955. The same year, he graduated from the Squadron Officer School at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama. From 1956 to 1959, he served as a flight commander in the 22nd Fighter Squadron, 36th Fighter Wing, stationed at Bitburg Air Base in West Germany, flying F-100 Super Sabres equipped with nuclear weapons. Among his squadron colleagues was Ed White, who had been a year behind him at West Point and later encouraged Aldrin to pursue a master's degree.

Through the Air Force Institute of Technology, Aldrin enrolled as a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1959, initially intending to earn a master's degree. He took an astrodynamics class taught by Richard Battin, which was also attended by future astronauts David Scott and Edgar Mitchell. Aldrin found the coursework engaging and soon decided to pursue a doctorate instead. In January 1963, he earned a Sc.D. degree in astronautics. His doctoral thesis, titled Line-of-Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous, was dedicated "In the hopes that this work may in some way contribute to their exploration of space, this is dedicated to the crew members of this country's present and future manned space programs. If only I could join them in their exciting endeavors!" Aldrin specifically chose this thesis topic hoping it would aid his selection as an astronaut, even though it meant forgoing test pilot training, which was a prerequisite for astronaut selection at the time.

After completing his doctorate, Aldrin was assigned to the Gemini Target Office of the Air Force Space Systems Division in Los Angeles. There, he collaborated with the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation to enhance the maneuver capabilities of the Agena target vehicle, which was crucial for NASA's Project Gemini. He was subsequently transferred to the Space Systems Division's field office at NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, where he played a role in integrating Department of Defense experiments into Project Gemini flights.

4. NASA Career

Aldrin's journey with NASA saw him selected as an astronaut and play critical roles in the Gemini and Apollo programs, culminating in his historic lunar landing.

4.1. Astronaut Selection and Training

Aldrin first applied to join the astronaut corps in 1962 when NASA Astronaut Group 2 was being selected. However, his application was rejected because he was not a test pilot, a requirement at the time. Despite his request for a waiver, it was denied. On May 15, 1963, NASA announced another round of selections, this time with a revised requirement that applicants possess either test pilot experience or 1,000 hours of flying time in jet aircraft. Aldrin, with over 2,500 hours of flying time, including 2,200 in jets, met this new criterion. His selection as one of fourteen members of NASA Astronaut Group 3 was announced on October 18, 1963. This made him the first astronaut with a doctoral degree, and his expertise in orbital mechanics earned him the nickname "Dr. Rendezvous" from his fellow astronauts. Although the nickname acknowledged his academic prowess, Aldrin was aware it was not always intended as a compliment. Upon completing initial training, Aldrin was assigned the specialized field of mission planning, trajectory analysis, and flight plans.

4.2. Gemini Program

Jim Lovell and Aldrin were initially selected as the backup crew for Gemini 10, with Lovell as commander and Aldrin as pilot. Typically, backup crews would become the prime crew for the third subsequent mission. However, with Gemini 12 being the last scheduled mission in the program, their path to a prime assignment was accelerated. The tragic deaths of the Gemini 9 prime crew, Elliot See and Charles Bassett, in a T-38 air crash on February 28, 1966, led to Lovell and Aldrin being moved up to backup for Gemini 9, which then positioned them as the prime crew for Gemini 12. Their designation as the prime crew was officially announced on June 17, 1966, with Gordon Cooper and Gene Cernan serving as their backups.

4.2.1. Gemini 12 Mission

The objectives for Gemini 12 were initially uncertain. As the final scheduled mission in the program, its primary purpose was to successfully complete tasks that had not been fully achieved on earlier missions. While NASA had successfully performed rendezvous maneuvers during Project Gemini, the gravity-gradient stabilization test on Gemini 11 had been unsuccessful. NASA also harbored concerns about extravehicular activity (EVA) due to fatigue experienced by astronauts like Cernan on Gemini 9 and Richard Gordon on Gemini 11. However, Michael Collins' successful EVA on Gemini 10 suggested that the order of task execution was a crucial factor.

It therefore became Aldrin's responsibility to fulfill Gemini's EVA goals. To enhance his chances of success, NASA established a committee. They removed the test of the Air Force's astronaut maneuvering unit (AMU), which had caused difficulties for Gordon on Gemini 11, allowing Aldrin to concentrate solely on EVA. NASA significantly revamped the training program, favoring underwater training over parabolic flight. While parabolic flights provided a brief experience of weightlessness, the delays between parabolas offered rest periods, which could encourage astronauts to perform tasks too quickly. Underwater training, using a viscous, buoyant fluid, offered a more accurate simulation of the continuous effort required in space. Additionally, NASA installed more handholds on the capsule, increasing them from nine on Gemini 9 to 44 on Gemini 12, and created workstations where Aldrin could anchor his feet.

Gemini 12's main objectives included rendezvous with a target vehicle, flying the spacecraft and target vehicle together using gravity-gradient stabilization, performing docked maneuvers with the Agena propulsion system to change orbit, conducting a tethered stationkeeping exercise, executing three EVAs, and demonstrating an automatic reentry. The mission also carried 14 scientific, medical, and technological experiments. Although it was not a trailblazing mission-rendezvous from above had been achieved by Gemini 9, and the tethered vehicle exercise by Gemini 11, and even gravity-gradient stabilization had been attempted by Gemini 11 (albeit unsuccessfully)-its success was critical for the future Apollo missions.

Gemini 12 launched from Launch Complex 19 at Cape Canaveral at 20:46 UTC on November 11, 1966, approximately one and a half hours after the Gemini Agena Target Vehicle. The mission's first major objective was to rendezvous with this target vehicle. As the target and Gemini 12 capsule approached, radar contact deteriorated, forcing the crew to perform the rendezvous manually. Aldrin utilized a sextant and rendezvous charts he had helped create to provide Lovell with the precise information needed to position the spacecraft for docking. Gemini 12 successfully achieved the fourth docking with an Agena target vehicle.

The next task involved practicing undocking and redocking. Upon undocking, one of the three latches became caught, requiring Lovell to use the Gemini's thrusters to free the spacecraft. Aldrin then successfully redocked a few minutes later. The flight plan originally called for the Agena's main engine to be fired to propel the docked spacecraft into a higher orbit. However, eight minutes after the Agena's launch, it experienced a loss of chamber pressure. Mission and Flight Directors decided not to risk the main engine, making this the only mission objective that was not achieved. Instead, the Agena's secondary propulsion system was used to allow the spacecraft to view and photograph the solar eclipse of November 12, 1966, over South America through the spacecraft windows.

Aldrin performed three EVAs during the mission. The first was a standup EVA on November 12, lasting two hours and twenty minutes, setting a new EVA record. During this, the spacecraft door was opened, and he stood up but did not fully exit the spacecraft. This standup EVA simulated some actions he would perform during his free-flight EVA, allowing for a comparison of effort. The following day, Aldrin conducted his free-flight EVA. He traversed the newly installed hand-holds to the Agena and connected the cable necessary for the gravity-gradient stabilization experiment. Aldrin successfully completed numerous tasks, including installing electrical connectors and testing tools crucial for Project Apollo. A dozen two-minute rest periods were incorporated to prevent him from experiencing fatigue. His second EVA concluded after two hours and six minutes. A third, 55-minute standup EVA was carried out on November 14, during which Aldrin took photographs, conducted experiments, and discarded unneeded items.

On November 15, the crew initiated the automatic reentry system and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean. They were then picked up by a helicopter and transported to the awaiting aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-18). After the mission, Aldrin's wife observed that he had fallen into a state of depression, a condition she had not witnessed in him before.

4.3. Apollo Program

Lovell and Aldrin were subsequently assigned to an Apollo crew alongside Neil Armstrong as commander, with Lovell as command module pilot (CMP) and Aldrin as lunar module pilot (LMP). Their assignment as the backup crew for Apollo 9 was announced on November 20, 1967. Due to unforeseen design and manufacturing delays in the lunar module (LM), Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 exchanged their prime and backup crews. As a result, Armstrong's crew became the backup for Apollo 8. Under the standard crew rotation scheme, Armstrong was then expected to command Apollo 11.

Michael Collins, the CMP on the Apollo 8 prime crew, required surgery to remove a bone spur on his spine. Lovell took his place on the Apollo 8 crew. Once Collins recovered, he rejoined Armstrong's crew as CMP. In the interim, Fred Haise served as backup LMP, and Aldrin as backup CMP for Apollo 8. Although the CMP typically occupied the center couch during launch, Aldrin took this position instead of Collins, as he had already been trained to operate its console during liftoff before Collins' return.

Apollo 11 marked only the second American space mission composed entirely of astronauts who had previously flown in space, the first being Apollo 10. The next such mission would not occur until STS-26 in 1988. Deke Slayton, who was responsible for astronaut flight assignments, offered Armstrong the option to replace Aldrin with Lovell, as some within NASA found Aldrin challenging to work with. Armstrong considered the offer for a day before declining, stating he had no issues working with Aldrin and believed Lovell deserved his own command.

Early versions of the EVA checklist had designated the lunar module pilot as the first to step onto the lunar surface. However, upon learning that this might be altered, Aldrin actively lobbied within NASA for the original procedure to be maintained. Multiple factors contributed to the final decision for Armstrong to be the first to exit the spacecraft, including the physical positioning of the astronauts within the compact lunar lander, which made it easier for Armstrong to egress. Furthermore, there was limited support for Aldrin's viewpoint among the senior astronauts who were slated to command later Apollo missions. Collins later commented that he believed Aldrin "resents not being first on the Moon more than he appreciates being second."

Aldrin and Armstrong had limited time for geological training, as the primary focus of the first lunar landing was on safely landing on the Moon and returning to Earth, rather than extensive scientific endeavors. The duo received briefings from NASA and USGS geologists. They conducted one geological field trip to West Texas, but the presence of the press and a noisy helicopter made it difficult for Aldrin and Armstrong to hear their instructor.

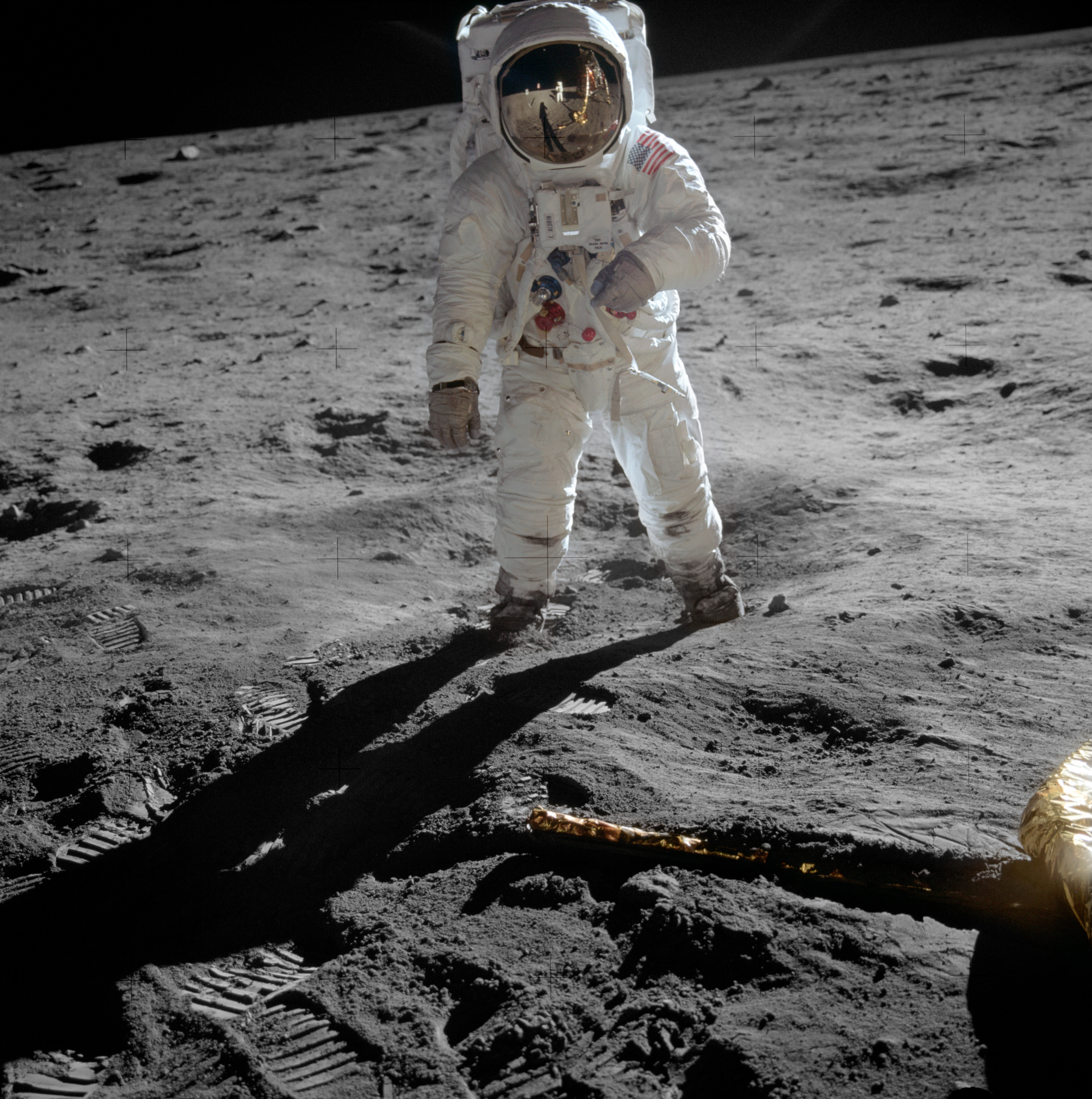

4.3.1. Apollo 11

On the morning of July 16, 1969, an estimated one million spectators gathered along the highways and beaches near Cape Canaveral, Florida, to witness the launch of Apollo 11. The launch was televised live in 33 countries, with an estimated 25 million viewers in the United States alone. Millions more listened to radio broadcasts. Propelled by a powerful Saturn V rocket, Apollo 11 lifted off from Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Center at 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT) on July 16, 1969. The spacecraft entered Earth orbit twelve minutes later. After one and a half orbits, the S-IVB third-stage engine ignited, pushing the spacecraft onto its trajectory toward the Moon. Approximately thirty minutes later, the critical transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver was performed. This involved separating the command module Columbia from the spent S-IVB stage, turning it around, and then docking with and extracting the lunar module Eagle. The combined spacecraft then set a course for the Moon, while the S-IVB stage continued on a trajectory past the Moon.

On July 19 at 17:21:50 UTC, Apollo 11 passed behind the Moon and fired its service propulsion engine to enter lunar orbit. Over the next thirty orbits, the crew observed their designated landing site in the southern Sea of Tranquillity, approximately 12 mile southwest of the crater Sabine D. At 12:52:00 UTC on July 20, Aldrin and Armstrong entered Eagle and began the final preparations for their lunar descent. At 17:44:00 UTC, Eagle successfully separated from Columbia. Collins, who remained alone aboard Columbia, then meticulously inspected Eagle as it pirouetted before him, ensuring the craft was undamaged and that its landing gear had correctly deployed.

5. Post-NASA Activities

After leaving NASA, Aldrin embarked on a new phase of his life, marked by personal challenges, continued advocacy for space exploration, and a prominent public presence.

5.1. Air Force Retirement

Aldrin had hoped to become Commandant of Cadets at the United States Air Force Academy, but the position was given to his West Point classmate Hoyt S. Vandenberg Jr.. Instead, Aldrin was appointed Commandant of the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California. Despite lacking managerial and test pilot experience, a third of the school's training curriculum was dedicated to astronaut training, and students flew a modified F-104 Starfighter to the edge of space. Fellow Astronaut Group 3 member and moonwalker Alan Bean considered Aldrin well-qualified for the role.

However, Aldrin's tenure was challenging, as he did not get along well with his superior, Brigadier General Robert M. White, who had earned his USAF astronaut wings flying the X-15. Aldrin's celebrity status often led staff to defer to him more than to the higher-ranking general. The base experienced two aircraft crashes, an A-7 Corsair II and a T-33, which, though not fatal, destroyed the aircraft and were attributed to insufficient supervision, placing blame on Aldrin. What he had anticipated as an enjoyable job became a highly stressful one.

Aldrin sought medical help for signs of depression, experiencing neck and shoulder pains, hoping a physical ailment might explain his mental state. He was hospitalized for depression at Wilford Hall Medical Center for four weeks. His mother had committed suicide in May 1968, and he was plagued with guilt that his fame after Gemini 12 might have contributed to her struggles. He also believed he inherited depression from his mother and her father, who had also committed suicide. At the time, there was significant stigma associated with mental illness, and Aldrin was acutely aware that it could not only end his career but also lead to social ostracization.

In February 1972, General George S. Brown visited Edwards and informed Aldrin that the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School was being renamed the USAF Test Pilot School, with astronaut training being discontinued. With the Apollo program winding down and Air Force budgets being cut, the Air Force's interest in space diminished. Aldrin chose to retire as a colonel on March 1, 1972, after 21 years of service. His father and General Jimmy Doolittle, a close friend of his father, attended the formal retirement ceremony.

5.2. Personal Struggles and Recovery

Aldrin's father passed away on December 28, 1974, due to complications following a heart attack. Aldrin's autobiographies, Return to Earth (1973) and Magnificent Desolation (2009), candidly recounted his struggles with clinical depression and alcoholism in the years following his departure from NASA. Encouraged by a therapist to find a regular job, Aldrin briefly attempted to sell used cars, a venture for which he admitted he had no talent. Periods of hospitalization and sobriety were interspersed with bouts of heavy drinking, eventually leading to his arrest for disorderly conduct. Finally, in October 1978, he quit drinking for good and has been a teetotaler ever since. Aldrin also sought to help others with drinking problems, including actor William Holden, whose alcohol-related death in 1981 deeply saddened him. Holden's girlfriend, Stefanie Powers, had portrayed Marianne, a woman with whom Aldrin had an affair, in the 1976 television movie adaptation of Return to Earth.

5.3. Advocacy for Space Exploration

After leaving NASA, Aldrin remained a fervent advocate for space exploration. In 1985, he joined the University of North Dakota (UND)'s College of Aerospace Sciences at the invitation of its dean, John D. Odegard. Aldrin played a key role in developing UND's Space Studies program and brought David C. Webb from NASA to serve as the department's first chair. To further promote space exploration and commemorate the 40th anniversary of the first lunar landing, Aldrin collaborated with musicians Snoop Dogg, Quincy Jones, Talib Kweli, and Soulja Boy to create the rap single and video "Rocket Experience," with proceeds donated to Aldrin's non-profit foundation, ShareSpace. He is also a member of the Mars Society's Steering Committee.

In 1985, Aldrin proposed a unique spacecraft trajectory now known as the Aldrin cycler. These cycler trajectories offer a more cost-effective approach to repeated travel to Mars by significantly reducing propellant requirements. The Aldrin cycler specifically outlined a five-and-a-half-month journey from Earth to Mars, with a return trip of the same duration on a twin cycler orbit. Aldrin continues to research this concept with engineers from Purdue University. In 1996, Aldrin founded Starcraft Boosters, Inc. (SBI) with the aim of designing reusable rocket launchers.

In December 2003, Aldrin published an opinion piece in The New York Times criticizing NASA's objectives. He expressed concern about NASA's development of an Orion spacecraft that was "limited to transporting four astronauts at a time with little or no cargo carrying capability." He also declared that the goal of sending astronauts back to the Moon felt "more like reaching for past glory than striving for new triumphs." In a subsequent opinion piece in The New York Times in June 2013, Aldrin strongly supported a human mission to Mars, viewing the Moon "not as a destination but more a point of departure, one that places humankind on a trajectory to homestead Mars and become a two-planet species." In August 2015, in collaboration with the Florida Institute of Technology, Aldrin presented a master plan to NASA for consideration, proposing that astronauts, with a ten-year tour of duty, establish a colony on Mars before the year 2040.

5.4. Public Life and Media Appearances

Aldrin has maintained an extensive public profile, engaging in numerous public speaking events and media appearances. He has authored several books, including autobiographies like Return to Earth (1973) and Magnificent Desolation (2009), as well as science fiction novels such as Encounter with Tiber (1996) and The Return (2000), and children's books like Reaching for the Moon (2005) and Look to the Stars (2009). He has also appeared in various documentaries, films, and television shows, often portraying himself, solidifying his status as a cultural icon.

5.5. Controversies and Incidents

During his public life, Aldrin has been involved in a few notable incidents and controversies.

On September 9, 2002, Aldrin was lured to a Beverly Hills hotel under the pretense of being interviewed for a Japanese children's television show about space. Upon his arrival, Moon landing conspiracy theorist Bart Sibrel accosted him with a film crew, demanding that Aldrin swear on a Bible that the Moon landings were not faked. After a brief confrontation, during which Sibrel persistently followed Aldrin despite being told to leave him alone and called him "a coward, a liar, and a thief," the 72-year-old Aldrin punched Sibrel in the jaw. The incident was captured on camera by Sibrel's film crew. Aldrin stated that he acted in self-defense and to protect his stepdaughter. Witnesses corroborated that Sibrel had aggressively poked Aldrin with a Bible. Given that Sibrel sustained no visible injury, did not seek medical attention, and Aldrin had no prior criminal record, the police declined to press charges against Aldrin.

In 2005, while being interviewed for a Science Channel documentary titled First on the Moon: The Untold Story, Aldrin mentioned that the Apollo 11 crew had seen an unidentified flying object (UFO). However, the documentary makers omitted the crew's subsequent conclusion that they had likely seen one of the four detached spacecraft adapter panels from the upper stage of the Saturn V rocket. These panels had been jettisoned before the separation maneuver and closely followed the spacecraft until the first mid-course correction. When Aldrin appeared on The Howard Stern Show on August 15, 2007, and was asked about the supposed UFO sighting, he clarified that there was no sighting of anything deemed extraterrestrial, stating they were "99.9 percent" sure the object was the detached panel. Aldrin maintained that his words had been taken out of context by the documentary and made an unsuccessful request to the Science Channel for a correction.

5.6. Other Activities

In December 2016, Aldrin participated in a tourist expedition to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. At 86 years of age, his visit made him the oldest person to reach the South Pole. He had previously traveled to the North Pole in 1998. During the South Pole trip, Aldrin fell ill and required evacuation, first to McMurdo Station and then to Christchurch, New Zealand, for medical treatment.

Aldrin is an active supporter of the Republican Party. He has headlined fundraisers for members of the United States Congress and endorsed various candidates. He appeared at a rally for George W. Bush during the 2004 presidential election and campaigned for Paul Rancatore in Florida in 2008, Mead Treadwell in Alaska in 2014, and Dan Crenshaw in Texas in 2018. He was a guest of President Donald Trump at the 2019 State of the Union Address. In the 2024 Presidential Election, he endorsed Donald Trump, citing Trump's promotion of space exploration policy as a key reason for his support. Aldrin stated, "For me, for the future of our Nation, to meet enormous challenges, and for the proven policy accomplishments above, I believe the nation is best served by voting for Donald J. Trump. I wholeheartedly endorse him for President of the United States. Godspeed President Trump, and God Bless the United States of America."

Buzz Aldrin holds the distinction of being the first Freemason to set foot on the Moon. He was initiated into Freemasonry at Oak Park Lodge No. 864 in Alabama and subsequently raised at Lawrence N. Greenleaf Lodge, No. 169 in Colorado. By the time he walked on the lunar surface, he was a member of two Masonic lodges: Montclair Lodge No. 144 in New Jersey and Clear Lake Lodge No. 1417 in Seabrook, Texas. He was also invited to serve on the High Council and was ordained in the 33rd degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. Additionally, Aldrin is a member of the York Rite and the Arabia Shrine Temple of Houston.

In 2007, Aldrin confirmed to Time magazine that he had recently undergone a face-lift, humorously remarking that the g-forces he experienced in space "caused a sagging jowl that needed some attention." Following the death of his Apollo 11 colleague Neil Armstrong in 2012, Aldrin expressed his deep sadness, stating, "I know I am joined by many millions of others from around the world in mourning the passing of a true American hero and the best pilot I ever knew... I had truly hoped that on July 20, 2019, Neil, Mike and I would be standing together to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of our moon landing." Since 1985, Aldrin has primarily resided in the Los Angeles area, including Beverly Hills and Laguna Beach. In 2014, he sold his Westwood condominium after his third divorce. He also maintains a residence in Satellite Beach, Florida.

6. Personal Life

Aldrin's personal life has included multiple marriages and family relationships, some of which have involved public disputes.

6.1. Marriages and Children

Aldrin has been married four times. His first marriage was on December 29, 1954, to Joan Archer, an alumna of Rutgers University and Columbia University with a master's degree. They had three children together: James, Janice, and Andrew. Their divorce was finalized in 1974. His second marriage was to Beverly Van Zile on December 31, 1975; they divorced in 1978. His third wife was Lois Driggs Cannon, whom he married on February 14, 1988. Their divorce was finalized in December 2012. The settlement included 50 percent of their 475.00 K USD bank account and 9.50 K USD a month, plus 30 percent of his annual income, which was estimated at more than 600.00 K USD. As of 2022, Aldrin had one grandson, Jeffrey Schuss, born to his daughter Janice, and three great-grandsons and one great-granddaughter. On January 20, 2023, his 93rd birthday, Aldrin announced on Twitter that he had married for the fourth time, to his 63-year-old companion, Anca Faur.

6.2. Family Disputes

In 2018, Aldrin became involved in a legal dispute with his children, Andrew and Janice, and his former business manager, Christina Korp. His children claimed that he was mentally impaired due to dementia and Alzheimer's disease, alleging that new friends were alienating him from the family and encouraging him to spend his savings at an unsustainable rate. They sought to be named his legal guardians to gain control over his finances. In June of that year, Aldrin filed a lawsuit against Andrew, Janice, Korp, and businesses and foundations run by the family. Aldrin alleged that Janice was not acting in his financial best interest and that Korp was exploiting him due to his age. He also sought to remove Andrew's control over his social media accounts, finances, and businesses. The situation was resolved in March 2019, several months before the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, when his children withdrew their petition and he dropped his lawsuit.

7. Awards and Honors

Aldrin has received numerous awards, honors, and recognitions throughout his distinguished military, spaceflight, and public careers, acknowledging his significant contributions to aviation and space exploration.

For his military service, Aldrin was awarded the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) in 1969 for his role as lunar module pilot on Apollo 11. He received an oak leaf cluster in 1972 in lieu of a second DSM, recognizing his contributions in both the Korean War and the space program. He was also awarded the Legion of Merit for his pivotal roles in the Gemini and Apollo programs.

During a 1966 ceremony marking the conclusion of the Gemini program, Aldrin was presented with the NASA Exceptional Service Medal by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the LBJ Ranch. He received the NASA Distinguished Service Medal in 1970 for the Apollo 11 mission.

Aldrin has been inducted into several prestigious halls of fame. He was one of ten Gemini astronauts inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 1982. In 1993, he was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame, followed by the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2000, and the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2008.

Among his other significant accolades, Aldrin received the Presidential Medal of Freedom (with distinction) from President Richard Nixon in 1969 following the Apollo 11 mission. In 1999, during the 30th anniversary celebration of the lunar landing, Vice President Al Gore, who also served as the vice-chancellor of the Smithsonian Institution's Board of Regents, presented the Apollo 11 crew with the Smithsonian Institution's Langley Gold Medal for aviation. After the ceremony, the crew visited the White House and presented President Bill Clinton with an encased Moon rock. The Apollo 11 crew was further honored with the New Frontier Congressional Gold Medal in the Capitol Rotunda in 2011, during which NASA administrator Charles Bolden remarked, "Those of us who have had the privilege to fly in space followed the trail they forged."

The Apollo 11 crew was awarded the Collier Trophy in 1969, with a duplicate trophy presented to Collins and Aldrin. They also received the 1969 General Thomas D. White USAF Space Trophy and were named the winners of the 1970 Dr. Robert H. Goddard Memorial Trophy by the National Space Club, an award given annually for the greatest achievement in spaceflight. In 1970, they received the international Harmon Trophy for aviators, which was conferred by Vice President Spiro Agnew in 1971. Agnew also presented them with the Hubbard Medal of the National Geographic Society in 1970, telling them, "You've won a place alongside Christopher Columbus in American history." In 1970, the Apollo 11 team were co-winners of the Iven C. Kincheloe award from the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, sharing the honor with Darryl Greenamyer for breaking the world speed record for piston engine airplanes. For their contributions to the television industry, they were honored with round plaques on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

In 2001, President George W. Bush appointed Aldrin to the Commission on the Future of the United States Aerospace Industry. Aldrin received the 2003 Humanitarian Award from Variety, the Children's Charity, which recognizes individuals who have demonstrated "unusual understanding, empathy, and devotion to mankind." In 2006, the Space Foundation awarded him its highest honor, the General James E. Hill Lifetime Space Achievement Award.

Aldrin has received honorary degrees from six colleges and universities and was named Chancellor of the International Space University in 2015. He was a member of the National Space Society's Board of Governors and has served as the organization's chairman. In 2016, his hometown middle school in Montclair, New Jersey, was renamed Buzz Aldrin Middle School in his honor. The Aldrin crater on the Moon, located near the Apollo 11 landing site, and Asteroid 6470 Aldrin are also named in his honor.

In 2019, Aldrin was awarded the Starmus Festival's Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication for Lifetime Achievement. On his 93rd birthday, he was honored by Living Legends of Aviation. On May 5, 2023, he received an honorary promotion to the rank of brigadier general in the United States Air Force and was also made an honorary Space Force guardian.

8. Legacy and Influence

Buzz Aldrin's legacy is profound and multifaceted, extending across space exploration, science, and popular culture. His pioneering spirit and unwavering dedication have left an indelible mark on humanity's quest to explore beyond Earth.

As the second person to walk on the Moon, Aldrin played a critical role in one of humanity's greatest achievements, inspiring generations to look to the stars. His scientific contributions, particularly his doctoral thesis on orbital rendezvous and his development of the Aldrin cycler, have provided foundational concepts for future space missions, especially for human travel to Mars. He remains a vocal and passionate advocate for space exploration, consistently championing the vision of humanity becoming a multi-planetary species.

Beyond his direct contributions to spaceflight, Aldrin has become a significant cultural icon. His name famously inspired the character Buzz Lightyear in the highly popular Toy Story franchise, introducing his legacy to a global audience, particularly children, and further embedding the spirit of space exploration in popular imagination. His public life, including his candid discussions about his personal struggles and recovery, has also made him a symbol of resilience and an advocate for mental health awareness. Through his books, public appearances, and media portrayals, Aldrin continues to influence public perception of space, emphasizing its importance for human progress and future aspirations.

9. Portrayal in Popular Culture

Buzz Aldrin has been a frequent presence in popular culture, appearing as himself in various productions and being portrayed by numerous actors.

Aldrin has appeared as himself in several films and television shows:

- 1976: The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (TV movie)

- 1986: Punky Brewster (episode "Accidents Happen")

- 1989: After Dark (extended appearance on British discussion program)

- 1994: The Simpsons (voice, episode "Deep Space Homer", where he accompanies Homer Simpson on a trip into space)

- 1997: Space Ghost Coast to Coast (episodes "Brilliant Number One" and "Brilliant Number Two")

- 1999: Disney's Recess (voice, episode "Space Cadet")

- 2003: Da Ali G Show (2 episodes)

- 2006: Numb3rs (episode "Killer Chat")

- 2007: In the Shadow of the Moon (documentary)

- 2008: Fly Me to the Moon

- 2010: 30 Rock (episode "The Moms")

- 2010: Dancing with the Stars (contestant, 2nd eliminated in season 10)

- 2011: Transformers: Dark of the Moon (he explains to Optimus Prime and the Autobots that Apollo 11's top secret mission was to investigate a Cybertronian ship on the far side of the Moon whose existence was concealed from the public)

- 2011: Futurama (voice, episode "Cold Warriors")

- 2012: Space Brothers

- 2012: The Big Bang Theory (episode "The Holographic Excitation")

- 2015: Jorden runt på 6 steg (successfully tested six degrees of separation)

- 2016: The Late Show with Stephen Colbert (interviewed and took part in a skit)

- 2016: Hell's Kitchen (dining room guest)

- 2017: Miles from Tomorrowland (voice, Commander Copernicus)

Aldrin has also been portrayed by other actors in various productions:

- Cliff Robertson in Return to Earth (1976), a role for which Aldrin worked with Robertson.

- Larry Williams in Apollo 13 (1995).

- Xander Berkeley in Apollo-11 (1996), for which Berkeley also served as a technical advisor.

- Bryan Cranston in From the Earth to the Moon (1998) and Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D (2005).

- James Marsters in Moonshot (2009).

- Cory Tucker as a younger Buzz Aldrin of 1969 in Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011).

- Corey Stoll in First Man (2018).

- Chris Agos in For All Mankind (2019, 6 episodes).

- Felix Scott in The Crown (2019).

- Roger Craig Smith (as real Buzz Aldrin) and Henry Winkler (as crisis actor Melvin Stupowitz) in Inside Job (2021-2022).

- Bryn Thomas in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023).

- Colin Woodell in Fly Me to the Moon (2024).

In video games, Aldrin was a consultant on Buzz Aldrin's Race Into Space (1993) and voiced the character of The Stargazer in Mass Effect 3 (2012). The character Buzz Lightyear from the Toy Story franchise was named in his honor.

10. Works

Aldrin has authored or co-authored several books across various genres, including autobiographies, science fiction novels, and children's books:

- Aldrin, Edwin E. Jr. 1970. "Footsteps on the Moon". Edison Electric Institute Bulletin. Vol. 38, No. 7, pp. 266-272.

- Armstrong, Neil; Michael Collins; Edwin E. Aldrin; Gene Farmer; and Dora Jane Hamblin. 1970. First on the Moon: A Voyage with Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Wayne Warga. 1973. Return to Earth. New York: Random House.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Malcolm McConnell. 1989. Men from Earth. New York: Bantam Books.

- Aldrin, Buzz and John Barnes. 1996. Encounter with Tiber. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Aldrin, Buzz and John Barnes. 2000. The Return. New York: Forge.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Wendell Minor. 2005. Reaching for the Moon. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Ken Abraham. 2009. Magnificent Desolation: The Long Journey Home from the Moon. New York: Harmony Books.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Wendell Minor. 2009. Look to the Stars. Camberwell, Vic.: Puffin Books.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Leonard David. 2013. Mission to Mars: My Vision for Space Exploration. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Books.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Marianne Dyson. 2015. Welcome to Mars: Making a Home on the Red Planet. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Children's Books.

- Aldrin, Buzz and Ken Abraham. 2016. No Dream Is Too High: Life Lessons from a Man Who Walked on the Moon. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Books.