1. Overview

Bernard of Clairvaux (Bernardus ClaraevallensisLatin; 1090 - August 20, 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was a highly influential French abbot, mystic, and theologian of the 12th century. He is recognized as a Catholic and Anglican saint and was designated a Doctor of the Church in 1830 by Pope Pius VIII. Bernard is often called "the Doctor Mellifluus" (Honey-flowing Doctor) due to his exceptional biblical commentary and rhetorical skill, reflecting the profound sweetness and depth of his spiritual writings.

Bernard played a pivotal role in the reform and rapid expansion of the Cistercian Order. He founded and served as the first abbot of Clairvaux Abbey, which became a dominant center of monastic life under his leadership. Beyond monasticism, Bernard was deeply involved in the ecclesiastical and political affairs of his era. He was instrumental in resolving the papal schism of 1130 by advocating for Pope Innocent II and actively engaged in numerous diplomatic missions.

As a prominent intellectual figure, he famously debated with Peter Abelard, influencing the condemnation of Abelard's teachings, and tirelessly worked to combat various heresies, including the Henricians and Petrobrusians. His most notable, though controversial, involvement in secular affairs was his powerful preaching that incited the Second Crusade across Europe. While his spiritual teachings emphasized a personal and affective relationship with Christ and significantly contributed to Mariology, his later life was marked by disappointment over the Crusade's failure and the heavy responsibility placed upon him. Bernard's multifaceted legacy encompasses his lasting impact on monasticism, theology, and Christian mysticism, alongside critical historical reassessments of his political actions and the complex outcomes of his influence. His iconography often includes symbols such as a beehive, symbolizing his eloquent preaching, a white dog, a book, and a chained demon, representing his spiritual battles. He is also considered the patron saint of beekeepers, candlemakers, sand extractors, and workers.

2. Early Life and Education

Bernard's early life was shaped by his noble lineage and a profound spiritual inclination that steered him away from a secular career toward monasticism.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Bernard was born in 1090 in Fontaine-lès-Dijon, a town near Dijon, France. He hailed from a wealthy and esteemed noble family of Burgundy. His father was Tescelin de Fontaine, the lord of Fontaine-lès-Dijon, and his mother was Alèthe de Montbard, a devout woman from a noble lineage in Montbard. Bernard was the third of seven children, six of whom were sons. His mother, Alèthe, was known for her deep faith and dedication to education; however, she passed away when Bernard was still young. Despite his family's aspirations for him to pursue a military career, Bernard harbored a strong desire for a religious life from an early age, influenced by his mother's piety.

2.2. Education and Spiritual Calling

As a young boy, Bernard was sent to a school at Châtillon-sur-Seine, which was run by the secular canons of Saint-Vorles. There, he received a formal education that included literature and rhetoric. During his studies with priests, he often contemplated entering the priesthood. His early inclination towards a religious vocation intensified, leading him to consider a life free from worldly entanglements within a monastery.

2.3. Entry into the Cistercian Order

Following his mother's death, Bernard definitively decided to embrace monastic life. In 1112, he sought admission to Cîteaux Abbey, a pioneering monastery in Burgundy that adhered strictly to the Rule of St. Benedict. Cîteaux Abbey had been founded in 1098 by Robert of Molesme with the aim of restoring the rigor and simplicity of early Benedictine monasticism, effectively establishing what would become the Cistercian Order.

Bernard's commitment to this reform was so compelling that in 1113, he arrived at Cîteaux not alone, but accompanied by 30 other young noblemen from Burgundy, many of whom were his relatives. This large influx of enthusiastic and idealistic novices, including his own father, revitalized the Cîteaux community, which had reportedly begun to lose its initial fervor. Bernard's powerful example and the sheer number of vocations he inspired led him to be regarded as a patron of religious callings.

3. Abbot of Clairvaux and Cistercian Reform

Bernard's leadership at Clairvaux Abbey and his tireless efforts for monastic reform were central to the rapid expansion and profound influence of the Cistercian Order across medieval Europe.

3.1. Founding of Clairvaux Abbey

Three years after Bernard entered Cîteaux, in 1115, the rapidly growing community of reformed Benedictines at Cîteaux needed to establish new houses. Bernard was chosen to lead a group of twelve monks to found a new monastery in a secluded area known as Vallée d'Absinthe, located in the Diocese of Langres. On June 25, 1115, Bernard officially established the new house, naming it Claire Vallée, which later became known as Clairvaux Abbey. From that point onward, the names of Bernard and Clairvaux became inextricably linked.

Bernard was appointed as the first abbot of Clairvaux by William of Champeaux, the Bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne. A strong friendship developed between the abbot and the bishop, who was also a professor of theology at Notre Dame de Paris and the founder of St. Victor Abbey in Paris. The early years of Clairvaux Abbey were characterized by extreme austerity, a practice to which Bernard himself adhered rigorously.

3.2. Expansion of the Cistercian Order

Under Bernard's zealous leadership, Clairvaux Abbey flourished, attracting a great number of candidates eager to embrace the strict Cistercian way of life. The success and spiritual reputation of Clairvaux, largely attributed to Bernard's fame and personality, led to the rapid proliferation of new Cistercian communities across Europe. Clairvaux soon began founding its own daughter houses: Trois-Fontaines Abbey was established in the diocese of Châlons in 1118, followed by Fontenay Abbey in the Diocese of Autun in 1119, and Foigny Abbey near Vervins in 1121.

Bernard's influence was so profound that during his lifetime, more than sixty abbeys were either newly founded or transferred to the Cistercian Order. Sources indicate that between 1130 and 1145 alone, at least 93 monasteries either joined or were newly established as Cistercian houses, extending the order's presence to regions as far as England and Ireland. While Cîteaux remained the formal center, Clairvaux emerged as the most significant and influential monastery within the burgeoning Cistercian network, driven by Bernard's compelling character and vision.

3.3. Monastic Life and Asceticism

Bernard of Clairvaux was known for his rigorous adherence to asceticism and contemplative practices, which deeply impacted both his physical health and spiritual development. He often suffered from illness, particularly since his novitiate, a direct result of his extreme fasting and austere lifestyle. His dedication to self-denial and holiness was a core aspect of his teachings; he advocated that a focus on changing human life, rather than relying solely on intellectual reason, was paramount. He emphasized the importance of humility before God as essential for spiritual purification, believing that such humility would lead to contemplation and a unity of human will with divine will, not a transformation of humans into God.

Despite his commitment to the enclosed contemplative life, Bernard spent considerable time outside the abbey, serving as a preacher and diplomat for the Pope. He was described by Jean-Baptiste Chautard as "the most contemplative and yet at the same time the most active man of his age," a duality Bernard himself acknowledged by calling himself the "chimera of his age." While he initially faced criticism for being excessively strict within the monastery, he eventually improved the conditions by strategically reducing the time spent on prayer, enhancing the quality of food, and strengthening internal unity with the help of the local bishop.

Bernard's personal experiences also deeply informed his spiritual teachings. The profound grief he experienced upon the death of his brother Gerard inspired one of his most moving sermons, which offered a unique perspective on the holiness of sorrow. Similarly, a personal trial occurred when a prior from the rival Abbey of Cluny visited Clairvaux in Bernard's absence and persuaded his cousin, Robert of Châtillon, to join the Benedictines, prompting Bernard to write one of his longest and most emotional letters.

3.4. Defense of the Cistercian Way of Life

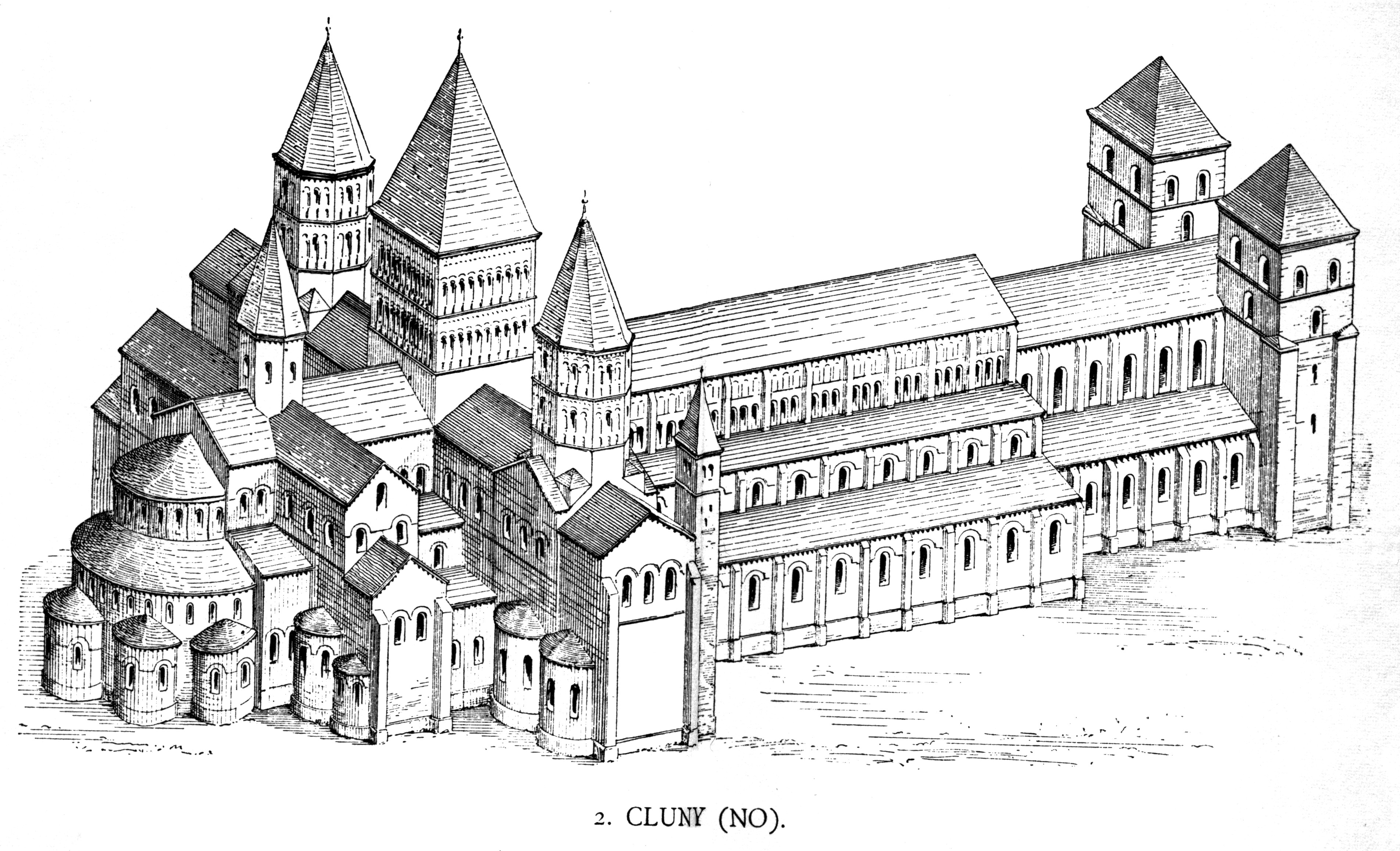

The rapid rise in prominence of Cîteaux and the Cistercian Order, particularly with many Benedictines converting to the Cistercian way of life, created friction with the older, more established Benedictine monasteries, especially the Abbey of Cluny. The Cluny Benedictines criticized the austere Cistercian lifestyle, viewing it as an implicit condemnation of their own practices.

In response to these criticisms, and at the urging of William of Saint-Thierry, Bernard wrote his famous Apology (Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici AbbatemLatin). In this work, Bernard defended the Cistercian ideals of simplicity, manual labor, and strict adherence to the Rule of St. Benedict, implicitly contrasting them with what he perceived as the excessive grandeur and laxity of some Cluniac monasteries. The abbot of Cluny, Peter the Venerable, responded to Bernard, expressing his admiration and friendship, acknowledging the validity of some of Bernard's points. Consequently, Cluny initiated its own internal reforms. Bernard also developed a friendship with Abbot Suger, the influential abbot of Saint-Denis, further bridging monastic divides. This exchange marked an important moment in medieval monastic history, solidifying the Cistercian identity and contributing to broader monastic reform efforts.

4. Theological and Spiritual Contributions

Bernard of Clairvaux left an indelible mark on medieval Christian thought through his distinct theological ideas, profound mystical experiences, deep devotion to the Virgin Mary, and his critical engagement with the burgeoning scholastic movement.

4.1. Mysticism and Devotion to Christ

Bernard's spirituality centered on a deeply personal and experiential faith, emphasizing a loving and immediate relationship with Jesus Christ. He is considered a master of prayer, advocating for direct affective engagement with the divine rather than solely intellectual understanding. Bernard's sermons and writings often employed poetic language and appeals to emotion, aiming to nurture a more immediate and profound faith experience in his audience. This approach positioned him as a master of Christian rhetoric, with his use of language being perhaps his most universal and enduring legacy.

He articulated the concept of divine love as the sole reason for loving God, famously stating, "The reason for loving God is God Himself" and "The measure of loving God is loving without measure." His spiritual teachings, rooted in love, explored the steps to humility as a path to spiritual purification, ultimately leading to contemplation and a union of human will with the divine will. His influential work, Sermons on the Song of Songs (Sermones super Cantica CanticorumLatin), profoundly explores this intimate relationship between the soul and Christ, using the allegorical language of the biblical text.

4.2. Mariology

Bernard made significant contributions to Mariology, the theological study of the Virgin Mary. He consistently insisted on Mary's central role in Christian theology and effectively promoted Marian devotions. Bernard preached extensively on her importance, which significantly influenced subsequent devotional practices throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. He developed theological ideas surrounding Mary's role as Co-Redemptrix and mediator, underscoring her indispensable position in the plan of salvation.

However, Bernard held a nuanced view regarding certain emerging Marian doctrines. Notably, he expressed disagreement with the concept of the Immaculate Conception, which posits that Mary was conceived without original sin. He argued that only Jesus Christ was conceived without sin, reflecting a theological position common among many prominent thinkers of his time before the doctrine was formally defined by the Church centuries later. Despite this particular stance, his overall veneration and theological reflections on Mary were highly influential and cemented her significant place in Christian devotion.

4.3. Critique of Scholasticism

Bernard of Clairvaux was a vocal opponent of the nascent Scholastic movement that characterized the 12th-century intellectual landscape. He criticized its overly rational and abstract approach to understanding God and Christian doctrine. While scholastic thinkers like Peter Abelard championed the use of logic and reason to systematize theology, Bernard advocated for a more emotional, mystical, and direct faith experience.

He believed that an excessive reliance on intellectual analysis could lead to spiritual aridity and detachment from the living experience of God. Bernard's emphasis was on conversion of life and inner transformation rather than mere intellectual ascent. This divergence in theological emphasis reflected a broader tension in medieval thought between faith and reason, with Bernard championing the primacy of spiritual wisdom gained through contemplation and personal encounter over systematic rational inquiry. His criticisms aimed to safeguard what he saw as the integrity of a heartfelt, living faith against the perceived dangers of intellectual pride and speculative theology.

4.4. Major Theological Works

Bernard of Clairvaux was a prolific writer, and his works, comprising treatises, sermons, and letters, profoundly shaped medieval spiritual and theological thought. The modern critical edition of his complete works is Sancti Bernardi operaLatin, published in eight volumes between 1957 and 1977, edited by Jean Leclercq.

His key treatises include:

- De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae (De gradibus humilitatis et superbiaeLatin, c. 1120, "On the Steps of Humility and Pride"): This work explores the monastic virtues through an analysis of twelve steps of humility and pride, drawing inspiration from the Rule of Saint Benedict.

- De conversione ad clericos sermo seu liberLatin (1122, "On the Conversion of Clerics"): A sermon or treatise addressed to scholars and student clerics, encouraging them towards a more dedicated spiritual life.

- Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici Abbatem (Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici AbbatemLatin, "Apology to William of St. Thierry"): Written in defense of the Cistercian Order against criticisms from the Benedictine monks of Cluny, asserting the validity of their reforms and austere lifestyle.

- De Gratia et Libero Arbitrio (De gratia et libero arbitrioLatin, c. 1128, "On Grace and Free Choice"): An academic theological work that examines the interplay between divine grace and human free will, a perennial theme in Christian theology.

- De diligendo Dei (De diligendo DeiLatin, "On Loving God"): A foundational text on spiritual love, in which Bernard argues that the only reason for loving God is God Himself, and the measure of that love is to love without measure.

- Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae (Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiaeLatin, 1129, "In Praise of the New Knighthood"): Written to support the newly emerging Knights Templar, this work defends the concept of a monastic-military order dedicated to defending the Holy Land.

- De praecepto et dispensatione libriLatin (c. 1144, "Book of Precepts and Dispensations"): Addresses issues of monastic obedience and the circumstances under which monastic rules might be relaxed.

- De consideratione (De considerationeLatin, c. 1150, "On Consideration"): Addressed to his former disciple, Pope Eugene III, this treatise advises the Pope on the spiritual and practical aspects of leadership, emphasizing that church reform should begin with the Pope himself and that piety and meditation must precede action.

- Liber De vita et rebus gestis Sancti Malachiae Hiberniae EpiscopiLatin ("The Life and Death of Saint Malachy, Bishop of Ireland"): A biography of his close friend, the Irish saint, written shortly after Malachy's death.

- De moribus et officio episcoporumLatin ("On the Conduct and Office of Bishops"): A letter-treatise addressed to Henri Sanglier, Archbishop of Sens, outlining the duties and moral responsibilities of bishops.

His sermons are also highly influential:

- The most famous are his Sermons on the Song of Songs (Sermones super Cantica CanticorumLatin). These 86 sermons, possibly originating from his addresses to the monks of Clairvaux, offer profound spiritual interpretations of the biblical Song of Songs, exploring the soul's loving relationship with God. They include autobiographical passages, such as Sermon 26, which movingly describes his mourning for his brother, Gerard.

- Additionally, 125 Sermones per annumLatin ("Sermons on the Liturgical Year") and numerous Sermones de diversisLatin ("Sermons on Different Topics") survive, demonstrating his wide range of pastoral and spiritual instruction.

Bernard's extensive correspondence includes 547 surviving letters, which provide valuable insights into the political, ecclesiastical, and spiritual issues of his time, as well as personal reflections.

4.5. Misattributed and Spurious Works

Due to Bernard's immense popularity and spiritual authority, numerous works were falsely attributed to him throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. These include:

- L'échelle du cloîtreFrench ("The Scale of the Cloister"): This letter-treatise, written around 1150, is now attributed to Guigo I, the 5th prior of the Grande Chartreuse.

- MeditatioLatin ("Meditations"): This work, likely written in the 13th century, circulated extensively under Bernard's name and became one of the most popular religious works of the later Middle Ages. Its central theme is self-knowledge as the beginning of wisdom, famously starting with the phrase "Many know much, but do not know themselves."

- L'édification de la maison intérieureFrench ("The Edification of the Inner House").

- The well-known hymn Jesu dulcis memoria ("Jesus, the very thought of Thee") was widely attributed to Bernard, though scholarly consensus now indicates it was not composed by him.

- The proverb "The road to hell is paved with good intentions" (L'enfer est plein de bonnes volontés ou désirsFrench) is often attributed to Bernard, including by Francis de Sales in a letter in 1604; however, no work by Bernard has been found to contain this specific proverb.

5. Role in Church Politics and Papal Schism

Bernard of Clairvaux was a central figure in 12th-century church politics, often acting as a diplomat and arbiter in major disputes, most notably in resolving the papal schism.

5.1. Diplomatic and Governance Activities

Bernard's profound spiritual authority and charismatic personality granted him an undeniable influence in the eyes of his contemporaries. His reputation for holiness, strict self-discipline, and eloquent preaching quickly spread, attracting not only numerous pilgrims to Clairvaux but also drawing him into the secular affairs of the time. By 1124, Bernard had become an indispensable figure in the French Church, with even Pope Honorius II seeking his counsel.

He actively defended the rights of the Church against perceived encroachments by kings and princes. Bernard recalled to their duty prominent churchmen who he felt were neglecting their responsibilities, such as Henri Sanglier, the Archbishop of Sens, and Stephen of Senlis, the Bishop of Paris. In 1129, at the invitation of Cardinal Matthew of Albano, Bernard participated in the Council of Troyes, where he worked effectively to secure the formal approval of the Knights Templar and helped outline their Rule, which became an ideal for Christian nobility. He also demonstrated his considerable skill in church governance by successfully resolving the issue of Bishop Henri of Verdun at the Council of Chalon, which ended with the bishop's resignation.

5.2. Resolution of the Papal Schism

Bernard's most decisive involvement in church politics occurred following the death of Pope Honorius II in 1130, which led to a major schism with the simultaneous election of two rival popes: Pope Innocent II and Antipope Anacletus II. Innocent II, having been banished from Rome by Anacletus, sought refuge in France.

King Louis VI of France convened a national council of French bishops at Étampes to address the crisis, and Bernard, summoned by the bishops, was chosen to arbitrate between the rival claimants. Despite Anacletus II's entrenched position in Rome with support from various countries, Bernard forcefully decided in favor of Innocent II, asserting that Innocent was "the pope accepted by the world."

Bernard then embarked on extensive diplomatic missions across Europe to secure recognition for Innocent II. He traveled to Italy, where he successfully reconciled Pisa with Genoa and brought Milan back to obedience to the Pope, having followed the deposed Archbishop Anselm V. While in Milan, Bernard was offered the prestigious Archbishopric of Milan, but he humbly refused, choosing instead to return to Clairvaux. He also attended the Council of Reims alongside Innocent II. Bernard played a crucial role in detaching William X, Duke of Aquitaine, from Anacletus's cause, although it required multiple visits and intense persuasion, with William finally pledging allegiance in 1135.

In Germany, Innocent II found a strong ally in Lothair II, Holy Roman Emperor, largely due to the efforts of Norbert of Xanten, a friend of Bernard's. Innocent insisted on Bernard's company when he met with Lothair II, further solidifying their alliance. Although councils in Étampes, Würzburg, Clermont, and Reims all supported Innocent, significant parts of the Christian world still acknowledged Anacletus. Bernard also engaged in a verbal battle with Gerard of Angoulême, whom he considered his most formidable opponent during the schism, ultimately convincing him.

In 1132, Bernard accompanied Innocent II to Italy, where at Cluny, the Pope abolished the dues Clairvaux had traditionally paid to that abbey, sparking a 20-year dispute between the Cistercians ("White Monks") and the Cluniacs ("Black Monks"). Although Lothair III's army helped Innocent enter Rome in May, Lothair's forces were too weak to resist Anacletus's partisans, forcing Innocent to seek refuge in Pisa in September 1133. Bernard, having returned to France, continued his peacemaking efforts. He made a second journey to Aquitaine in late 1134, where William X had relapsed into schism. During a Mass, Bernard famously "admonished the Duke not to despise God as he did His servants," leading to William's submission and the end of the schism in Aquitaine.

In 1137, Bernard was again compelled to leave Clairvaux by papal order to mediate a dispute between Lothair and Roger II of Sicily. At a conference in Palermo, Bernard successfully convinced Roger of Innocent II's legitimate rights and silenced the remaining supporters of the schism. When Anacletus died in 1138, reportedly from "grief and disappointment," the schism effectively concluded. In 1139, Bernard assisted at the Second Council of the Lateran, which definitively condemned the remaining adherents of the schism, restoring unity to the Church. Around the same time, Bernard was visited at Clairvaux by Saint Malachy, the Primate of All Ireland, and a close friendship formed between them. Malachy, who desired to become a Cistercian, died at Clairvaux in 1148.

6. Intellectual Debates and Combating Heresy

Bernard of Clairvaux was a staunch defender of orthodox Christian doctrine, actively engaging in key intellectual debates of his time and leading efforts to suppress what he considered heresies.

6.1. Debate with Peter Abelard

Towards the close of the 11th century, a spirit of intellectual independence flourished in schools of philosophy and theology, finding a powerful advocate in Peter Abelard. Abelard's treatise on the Trinity had already been condemned as heretical in 1121, forcing him to destroy his own book. However, Abelard continued to develop and spread his controversial teachings.

Bernard initially met with Abelard, intending to persuade him to revise his writings, and Abelard reportedly repented and promised to comply. Yet, once out of Bernard's presence, he renounced his promise. Bernard then denounced Abelard to the Pope and the cardinals of the Roman Curia. Abelard, confident in his dialectical skills, sought a public debate with Bernard. Bernard initially declined, stating that matters of such profound importance should not be settled by mere logical analyses, and his letters to William of Saint-Thierry expressed apprehension about confronting the renowned logician.

However, Abelard continued to press for a public confrontation, making his challenge widely known and making it difficult for Bernard to refuse. In 1141, at Abelard's urging, the Archbishop of Sens called a council of bishops in Sens, where both Bernard and Abelard were to present their respective cases, allowing Abelard an opportunity to clear his name. On the eve of the debate, Bernard actively lobbied the prelates, swaying many to his point of view. The following day, after Bernard delivered his opening statement, Abelard chose to withdraw without attempting a rebuttal. The council ruled in favor of Bernard, and their judgment was subsequently confirmed by the Pope. Abelard submitted without resistance and retired to Cluny, living under the protection of Peter the Venerable until his death two years later.

6.2. Opposition to Heresies

Bernard had occupied himself in sending bands of monks from his overcrowded monastery into Germany, Sweden, England, Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland, and Italy. Some of these, at the command of Innocent II, took possession of Tre Fontane Abbey. In 1145, one of Bernard's disciples, Bernard of Pisa, was chosen as Pope, becoming Pope Eugene III. At the new Pope's request, Bernard sent him various instructions that comprise his widely quoted work, De consideratione, whose main argument posited that church reform must begin with the Pope, emphasizing piety and meditation as prerequisites for action.

Bernard actively preached against movements like the Henricians, followers of Henry of Lausanne, and the Petrobrusians, followers of Peter of Bruys. Henry of Lausanne, a former Cluniac monk, had adopted and modified Peter of Bruys' teachings after the latter's death, spreading them throughout southern France. In June 1145, invited by Cardinal Alberic of Ostia, Bernard traveled to the region. His powerful preaching, amplified by his ascetic appearance and simple attire, proved highly effective in undermining the new sects. Both the Henrician and Petrobrusian movements began to decline significantly by the end of that year. Henry of Lausanne was eventually arrested, brought before the Bishop of Toulouse, and likely imprisoned for life. In a letter to the people of Toulouse, written in late 1146, Bernard urged them to eradicate any remaining traces of the heresy. He also preached against Catharism, another significant heterodox movement.

Bernard's influence, however, was not absolute. Prior to the second hearing of Gilbert of Poitiers at the Council of Reims in 1148, Bernard held a private meeting with several attendees, attempting to pressure them into condemning Gilbert. This move offended the cardinals present, who insisted that only they had the authority to judge the case. Consequently, no verdict of heresy was ultimately rendered against Gilbert, illustrating the limits of Bernard's power in certain ecclesiastical contexts.

7. Preaching and the Crusades

Bernard of Clairvaux was a renowned and influential preacher, whose sermons extended beyond monastic settings to significantly shape public opinion and political action, most notably in the context of the Crusades.

7.1. Monastic and Clerical Preaching

As the abbot of Clairvaux, Bernard frequently delivered sermons to his monastic community, which form the basis of his extensive collections of homilies. Among the most famous of these are his Sermons on the Song of Songs (Sermones super Cantica CanticorumLatin), which are often studied for their profound spiritual insights and mystical interpretations. These sermons, addressed primarily to the monks at Clairvaux, exemplify his rhetorical skill and deep theological understanding.

Beyond his monastic audience, Bernard also preached to other religious communities and, in a particularly notable instance, to students of theology in Paris. His sermon Ad clericos de conversioneLatin ("To Clerics on Conversion"), delivered in 1139 or early 1140 to a gathering of scholars and student clerics, demonstrates his ability to adapt his spiritual and pastoral content to different audiences, urging them towards a life of deeper faith and conversion. His sermons were characterized by a poetic and affective style, designed to foster an immediate and personal experience of faith, rather than an abstract intellectual understanding.

7.2. Incitement of the Second Crusade

In the mid-12th century, alarming news reached Christendom from the Holy Land: the Christian stronghold of Edessa had fallen to the Seljuk Turks in 1144 after a devastating siege, and the entire County of Edessa was lost. This defeat severely threatened the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader states. Deputations from the bishops of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and ambassadors from the King of France urgently sought aid from the Pope.

In 1144, Pope Eugene III, a former disciple of Bernard's, commissioned his mentor to preach the Second Crusade and granted the same indulgences that Pope Urban II had offered for the First Crusade. Initially, there was little popular enthusiasm for a new crusade, unlike the fervent response of 1095. Bernard, therefore, emphasized the act of "taking the cross" as a potent means of gaining absolution for sins and attaining divine grace.

On March 31, 1146, with King Louis VII of France present, Bernard delivered what was described as "the speech of his life" to an enormous crowd gathered in a field at Vézelay. His sermon was extraordinarily compelling; many listeners immediately enlisted, so many that they reportedly ran out of the cloth used to make crosses for the new recruits. Unlike the First Crusade, this new venture attracted high-ranking royalty, including King Louis VII, his queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, and numerous aristocrats and bishops. Even greater support came from the common people. Bernard wrote to Pope Eugene a few days later, lamenting that "Cities and castles are now empty. There is not left one man to seven women, and everywhere there are widows to still-living husbands," illustrating the widespread popular fervor.

Bernard then traveled to Germany, where his mission was further aided by reports of miracles. King Conrad III of Germany and his nephew Frederick Barbarossa personally received the cross from Bernard's hand, signifying widespread royal commitment. Pope Eugenius III himself came to France to encourage the enterprise.

7.3. Advocacy for the Wendish Crusade

Bernard of Clairvaux did not personally preach the Wendish Crusade (1147), but he issued a crucial letter that strongly advocated for military action against the pagan Wends, a group of Western Slavs residing in Northern Europe. This letter argued that the Wends should not be allowed to obstruct the broader efforts of the Second Crusade against the Muslims in the Holy Land.

In his correspondence, Bernard explicitly supported battling the Wends "until such a time as, by God's help, they shall either be converted or deleted." A decree issued in Frankfurt mandated that Bernard's letter be widely proclaimed and read aloud, effectively ensuring that "the letter functioned as a sermon" across the region. This advocacy highlights Bernard's belief in the use of force for the expansion of Christianity, even against non-Muslims, within the broader context of the crusading movements of the time.

7.4. Impact and Criticism of Crusade Preaching

The widespread and passionate preaching of the Second Crusade by Bernard of Clairvaux, while initially highly successful in galvanizing support, unfortunately led to negative side effects, particularly attacks on Jewish communities. A fanatical French monk named Radulf the Cistercian began inspiring massacres of Jews in the Rhineland, including cities like Cologne, Mainz, Worms, and Speyer. Radulf falsely claimed that Jews were not contributing financially to the effort to reclaim the Holy Land, fueling anti-Jewish violence.

The archbishops of Cologne and Mainz vehemently opposed these attacks and requested Bernard to publicly denounce them. Bernard did so, but when Radulf's campaign continued, Bernard personally traveled from Flanders to Germany to address the problem. He located Radulf in Mainz, successfully silenced him, and ordered him to return to his monastery, effectively ending the massacres.

Despite Bernard's efforts to curb the violence against Jews, the ultimate failure of the Second Crusade, which concluded in widespread defeat and disappointment, cast a long shadow over his later years. Bernard found himself bearing the entire responsibility for the crusade's outcome. He sent an apology to the Pope, which was included in the second part of his De consideratione (Book of Considerations). In this apology, he attributed the crusaders' misfortunes and failures primarily to their own sins, offering a theological justification for the military debacle. This event, and the subsequent critical assessment of its outcome, significantly weakened Bernard's influence in the final years of his life.

8. Later Life and Death

The final years of Bernard's life were marked by a period of reflection on mortality and a quiet contemplation of his extensive legacy, culminating in his peaceful death.

8.1. Final Years and Reflections

As Bernard approached the end of his life, the deaths of his contemporaries served as poignant warnings of his own impending demise. In 1152, he mourned the passing of Abbot Suger, the influential abbot of Saint-Denis, writing to Pope Eugene III that "If there is any precious vase adorning the palace of the King of Kings it is the soul of the venerable Suger." The same year, both King Conrad III of Germany and his son Henry also died.

Although physically frail from years of severe asceticism and tireless work, Bernard's mental acuity remained sharp until his death. This is evident in his final major work, De consideratione (On Consideration), a profound treatise addressed to his former disciple, Pope Eugene III. In this work, Bernard reflects on the spiritual and practical aspects of papal leadership, urging the Pope to prioritize piety and meditation over temporal affairs. His clear-headedness in composing such a significant work even in his declining health testifies to his enduring intellectual vigor.

His later years also saw a decline in his political influence, particularly following the disastrous failure of the Second Crusade, which he had so fervently preached. While there were discussions of launching a new crusade, and Bernard was even asked by the Pope to lead it, he fortunately was exempted due to his responsibilities as abbot of Clairvaux. Amidst various ongoing debates, conflicts, and the deaths of close friends, Bernard increasingly turned his focus inward, preparing for his final journey.

8.2. Death and Burial

Bernard of Clairvaux died at the age of sixty-three on August 20, 1153, after dedicating forty years of his life to monastic service. He passed away peacefully at Clairvaux Abbey, the very institution he had founded and led for decades. He was initially buried within the abbey grounds, which served as his spiritual home and the center of his vast influence.

However, during the turbulent period of the French Revolution in 1792, Clairvaux Abbey was destroyed. Consequently, Bernard's remains were transferred for safekeeping to Troyes Cathedral, where they rest today. Bernard was the first Cistercian monk to be formally recorded in the calendar of saints, a testament to his immediate and widespread veneration.

9. Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Bernard of Clairvaux's profound influence extended across theology, monasticism, and even into the intellectual currents that shaped the Reformation. His legacy is complex, prompting both veneration and critical reassessment.

9.1. Influence on Later Thought and the Reformation

Bernard's theology and Mariology continue to hold significant importance in Christian thought, with his texts remaining prescribed reading in Cistercian congregations today. His spiritual writings, particularly his emphasis on an affective and personal relationship with Christ, resonated deeply throughout the medieval period and beyond.

Notably, Bernard's ideas had a surprising impact on key figures of the Protestant Reformation. Both John Calvin and Martin Luther quoted Bernard multiple times in support of the doctrine of Sola Fide (justification by faith alone), which was a cornerstone of their theological reforms. Calvin, for instance, also referenced Bernard in explaining his doctrine of forensic alien righteousness, commonly known as imputed righteousness. Bernard's emphasis on grace and a direct, experiential faith, rather than solely on human merit or elaborate intellectual systems, represented a "fundamental reorientation" within medieval theology, subtly foreshadowing aspects of the Reformation's emphasis on individual faith and divine grace.

Bernard's influence also permeated literature and art. He serves as Dante Alighieri's final guide in the celestial realms of Paradiso within the Divine Comedy, reflecting his perceived spiritual authority and insight. Additionally, the well-known hymn "Jesu dulcis memoria" (Jesus, the very thought of Thee) was widely attributed to Bernard for centuries, though modern scholarship suggests it was a later, spurious attribution.

9.2. Recognition as Saint and Doctor of the Church

Bernard of Clairvaux's enduring spiritual authority and profound contributions were formally recognized by the Catholic Church. Just 21 years after his death, on January 18, 1174, he was canonized as a saint by Pope Alexander III.

Centuries later, in 1830, Pope Pius VIII further honored him by declaring him a Doctor of the Church, a title bestowed upon saints whose writings and preachings are considered to be of outstanding theological and doctrinal significance to the universal Church. In 1953, to commemorate the 800th anniversary of his death, Pope Pius XII dedicated an entire encyclical, Doctor Mellifluus, to Bernard, in which he lauded the abbot as "the last of the Fathers," acknowledging him as a culmination of the patristic tradition. This designation underscores his reputation for eloquent and spiritually rich biblical commentary. Numerous churches and chapels worldwide bear his name as their patron saint, and his feast day is celebrated on August 20. The Couvent et Basilique Saint-Bernard, a collection of buildings spanning the 12th, 17th, and 19th centuries, stands in his birthplace of Fontaine-lès-Dijon as a testament to his lasting veneration.

9.3. Contribution to Monasticism and Cistercianism

Bernard of Clairvaux's most direct and immediate legacy lies in his transformative impact on medieval monasticism, particularly the Cistercian Order. As the first abbot of Clairvaux, he implemented a rigorous interpretation of the Rule of Saint Benedict, emphasizing asceticism, manual labor, and spiritual simplicity. His personal charisma, unwavering dedication, and reputation for holiness attracted an unprecedented number of vocations, leading to the rapid expansion of the order.

Under his guidance, Clairvaux became a mother abbey, founding numerous daughter houses across Europe. Bernard directly oversaw the establishment of over sixty new abbeys during his lifetime, and the Cistercian Order as a whole saw at least 93 monasteries either founded or brought under its influence between 1130 and 1145. This explosive growth effectively solidified the Cistercian Order as one of the most dynamic and influential monastic movements of the High Middle Ages. Cistercians continue to honor him as one of their greatest early figures, recognizing his foundational role in shaping their distinctive way of life and spiritual ethos. His contributions reshaped monastic traditions, emphasizing a return to strict observance and contributing to the spiritual renewal of the Church.

9.4. Critical Perspectives and Reassessment

Despite his veneration as a saint and Doctor of the Church, Bernard of Clairvaux is also acknowledged as "a difficult saint," and historical reassessments have presented a more nuanced view of his actions and influence. His strong convictions and willingness to intervene in worldly affairs, while contributing to his widespread impact, also led to outcomes that have faced modern criticism.

His involvement in the Second Crusade stands as a primary example. While Bernard's passionate preaching initially garnered immense popular support, the crusade ultimately ended in a disastrous failure, for which he was heavily blamed. Furthermore, his sermons inadvertently incited violent attacks against Jewish communities in the Rhineland, leading him to personally intervene to halt the massacres instigated by the fanatical monk Radulf. This episode highlights the complex and sometimes unintended consequences of his powerful rhetoric.

Bernard's role in the condemnation of Peter Abelard also draws scrutiny. Critics argue that Bernard, prioritizing faith and spiritual experience, may have stifled legitimate theological inquiry and rational discourse. While Bernard genuinely believed he was defending orthodoxy, his methods sometimes involved intense lobbying and pressure tactics, as seen at the Council of Sens and his efforts against Gilbert of Poitiers. His strong stance against figures he deemed heretical, while in line with the ecclesiastical norms of his time, is viewed by some as contributing to an atmosphere of intellectual intolerance.

These critical perspectives do not diminish his profound spiritual contributions but offer a more balanced historical evaluation, acknowledging the complex and sometimes problematic dimensions of his immense power and influence in the 12th century. His legacy, therefore, encompasses both his revered spiritual insights and the challenging aspects of his engagement with the political and intellectual struggles of his era.

10. Major Works

Bernard of Clairvaux was a prolific writer whose extensive literary output includes significant theological treatises, numerous sermons, and a vast collection of letters, alongside works that were later found to be falsely attributed to him. The definitive modern critical edition of his collected works is Sancti Bernardi operaLatin, meticulously edited by Jean Leclercq.

10.1. Key Treatises

Bernard's theological and spiritual insights are primarily conveyed through his treatises, which address a wide range of doctrinal and monastic themes:

- De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae (De gradibus humilitatis et superbiaeLatin, "The Steps of Humility and Pride"): Written around 1120, this work provides a detailed exposition of the monastic virtues, drawing inspiration from the Rule of Saint Benedict.

- Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici Abbatem (Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici AbbatemLatin, "Apology to William of St. Thierry"): This treatise was a defense of the Cistercian way of life against the criticisms and claims made by the monks of Cluny.

- De conversione ad clericos sermo seu liberLatin ("On the Conversion of Clerics"): From 1122, this is a sermon or book aimed at clerics, urging them towards spiritual conversion.

- De Gratia et Libero Arbitrio (De gratia et libero arbitrioLatin, "On Grace and Free Choice"): Composed around 1128, this academic theological work explores the complex relationship between divine grace and human free will.

- De diligendo Dei (De diligendo DeiLatin, "On Loving God"): A cornerstone of Christian mysticism, this treatise articulates Bernard's central theme that the only reason to love God is God Himself, and the only measure of that love is to love without measure.

- Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae (Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiaeLatin, "In Praise of the New Knighthood"): Written in 1129, this work provides a spiritual and theological justification for the Knights Templar, celebrating their unique combination of monastic and military life.

- De praecepto et dispensatione libriLatin (c. 1144, "Book of Precepts and Dispensations"): Addresses issues of monastic obedience and the circumstances under which monastic rules might be relaxed.

- De consideratione (De considerationeLatin, c. 1150, "On Consideration"): Addressed to his former disciple, Pope Eugene III, this treatise advises the Pope on the spiritual and practical aspects of leadership, emphasizing that church reform should begin with the Pope himself and that piety and meditation must precede action.

- Liber De vita et rebus gestis Sancti Malachiae Hiberniae EpiscopiLatin ("The Life and Death of Saint Malachy, Bishop of Ireland"): This is a biographical account of his close friend, Saint Malachy, offering insights into monastic life and spiritual friendship.

- De moribus et officio episcoporumLatin ("On the Conduct and Office of Bishops"): A letter-treatise addressed to Henri Sanglier, Archbishop of Sens, detailing the moral and pastoral responsibilities of bishops.

10.2. Sermons

Bernard's sermons are renowned for their spiritual depth and rhetorical brilliance, profoundly influencing devotional literature.

- His most famous collection is Sermons on the Song of Songs (Sermones super Cantica CanticorumLatin). These 86 sermons, possibly originating from his addresses to the monks of Clairvaux, offer intricate allegorical interpretations of the biblical Song of Songs, exploring the mystical union between Christ and the soul. Sermon 26 contains a poignant autobiographical passage mourning the death of his brother, Gerard. After Bernard's death, the English Cistercian Gilbert of Hoyland continued this incomplete series.

- Additionally, 125 surviving Sermones per annumLatin ("Sermons on the Liturgical Year") and numerous Sermones de diversisLatin ("Sermons on Different Topics") demonstrate his wide range of pastoral and spiritual instruction.

10.3. Letters

Bernard's extensive correspondence comprises 547 surviving letters. These letters are invaluable historical and spiritual documents, offering insights into his personal thoughts, his engagement with contemporary ecclesiastical and political issues, and his advice on spiritual matters to a wide array of correspondents, from popes and kings to fellow monastics and lay individuals.

10.4. Misattributed and Spurious Works

Due to Bernard's immense popularity and spiritual authority, numerous works were falsely attributed to him throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. These include:

- L'échelle du cloîtreFrench ("The Scale of the Cloister"): This letter-treatise, written around 1150, is now attributed to Guigo I, the 5th prior of the Grande Chartreuse.

- MeditatioLatin ("Meditations"): This work, likely written in the 13th century, circulated extensively under Bernard's name and became one of the most popular religious works of the later Middle Ages. Its central theme is self-knowledge as the beginning of wisdom, famously starting with the phrase "Many know much, but do not know themselves."

- L'édification de la maison intérieureFrench ("The Edification of the Inner House").

- The well-known hymn Jesu dulcis memoria ("Jesus, the very thought of Thee") was widely attributed to Bernard, though scholarly consensus now indicates it was not composed by him.

- The proverb "The road to hell is paved with good intentions" (L'enfer est plein de bonnes volontés ou désirsFrench) is often attributed to Bernard, including by Francis de Sales in a letter in 1604; however, no work by Bernard has been found to contain this specific proverb.