1. Overview

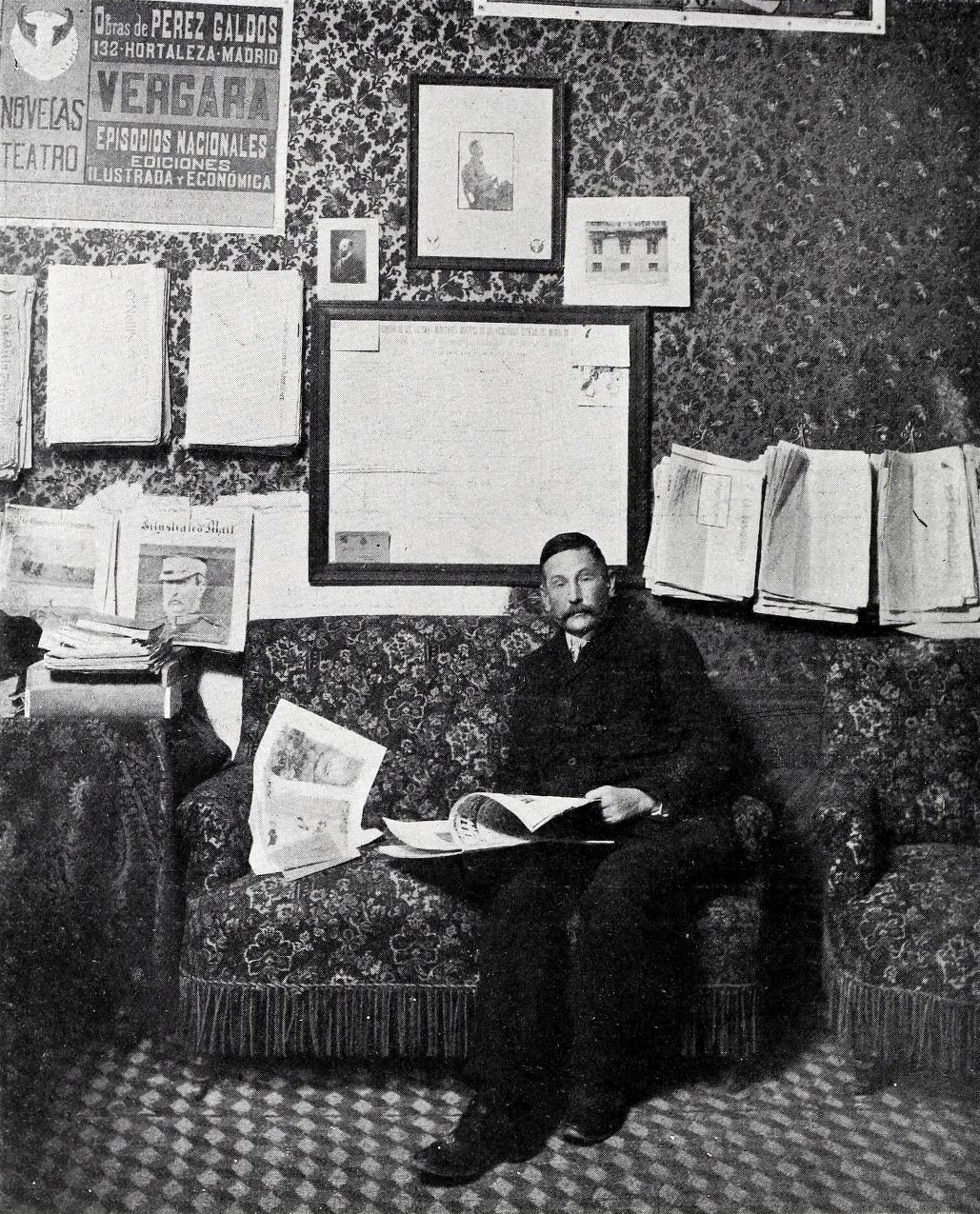

Benito Pérez Galdós, born Benito María de los Dolores Pérez Galdós (1843-1920), was a preeminent Spanish realist novelist and a leading literary figure in 19th-century Spain. Widely regarded by many scholars as the greatest Spanish novelist since Miguel de Cervantes, he is often compared in stature to literary giants such as Charles Dickens, Honoré de Balzac, and Leo Tolstoy. A remarkably prolific writer, Pérez Galdós published 31 major novels, 46 historical novels in his monumental Episodios Nacionales (National Episodes) series, 23 plays, and an extensive collection of shorter fiction, journalism, and other writings.

His works are celebrated for their meticulous research, detailed depiction of Spanish life, and profound social commentary. From a center-left perspective, Pérez Galdós is particularly noted for his progressive ideas, including his consistent criticism of clericalism and conservative power, and his nuanced portrayal of various social strata and the human condition in his era. He evolved politically from liberalism to republicanism and eventually embraced socialist ideas, demonstrating a deep engagement with the social and political movements of his time. Despite his immense literary contributions and multiple Nobel Prize nominations, his anti-clerical stance and progressive political views led to boycotts from conservative sectors of Spanish society, affecting his international recognition during his lifetime. Nevertheless, he remains highly popular in Spain, with his legacy enduring through his powerful narrative voice and lasting influence on Spanish literature.

2. Biography

The life trajectory of Benito Pérez Galdós, from his early years to his final days, details key personal and professional developments, marked by his dedication to writing and his engagement with the political and social issues of his time.

2.1. Early Life and Education

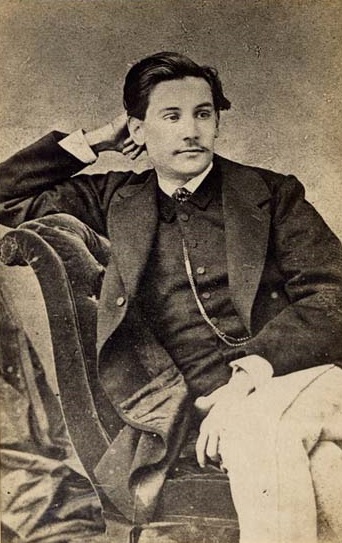

Benito Pérez Galdós was born on May 10, 1843, in Calle Cano in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain. He was the tenth and last child of Lieutenant Colonel Don Sebastián Pérez and Doña Dolores Galdós. Two days after his birth, he was baptized Benito María de los Dolores at the church of San Francisco de Asís. The house where he was born is now preserved as the Casa-Museo de Pérez Galdós.

Pérez Galdós received his early education at San Agustín school, where his teachers were influenced by the principles of the Enlightenment. In 1862, after completing his secondary studies, he traveled to Tenerife to obtain his certificate in bachillerato in arts. That same year, at the age of 19, he moved to Madrid to commence a law degree, though he ultimately did not complete his studies. While attending university, Pérez Galdós frequently visited the Ateneo de Madrid, a prominent intellectual hub, and other gatherings of intellectuals and artists. This period allowed him to familiarize himself deeply with life in Madrid and to witness firsthand the significant political and historical events of the era, which later influenced his journalistic works and early novels, such as La Fontana de oro (The Golden Fountain Café) (1870) and El audaz (The Daring) (1871).

2.2. Early Literary Activities

Pérez Galdós embarked on his literary career with initial forays into journalism and playwriting. By 1865, he began publishing articles in La Nación, covering diverse topics including literature, art, music, and politics. Between 1861 and 1867, he completed three plays, though none were published at the time. A significant early contribution was his 1868 translation of Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers, which played a crucial role in introducing Dickens' work to the Spanish public. In 1870, Pérez Galdós was appointed editor of La Revista de España, a platform through which he expressed his informed opinions on a wide range of subjects, from history and culture to contemporary politics and literature.

His first novel, La Fontana de Oro, a historical work set between 1820 and 1823, was written between 1867 and 1868 and privately published in 1870 with financial assistance from his sister-in-law. While initial critical reaction was slow, the novel eventually gained recognition as ushering in a new phase of Spanish fiction, receiving praise for both its literary quality and its social and moral objectives.

2.3. Writing Career

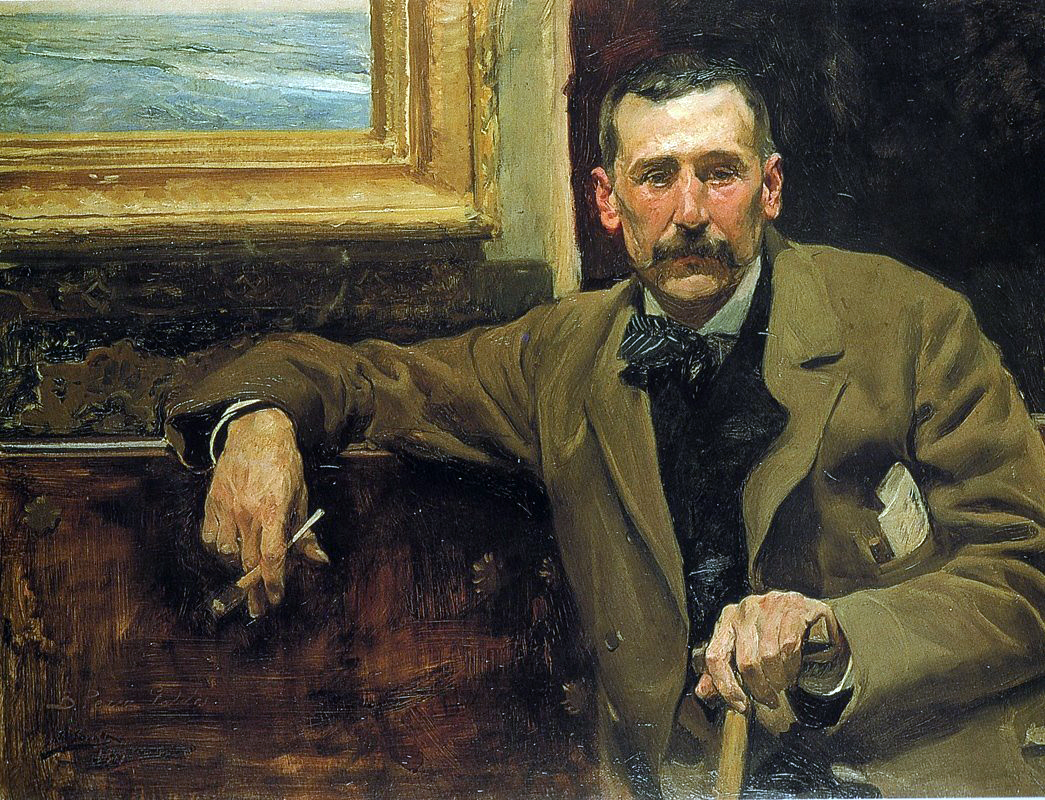

Pérez Galdós maintained a disciplined and consistent writing routine. He typically rose at sunrise and wrote regularly until ten o'clock in the morning, often using a pencil, as he considered the use of a pen a waste of time. Following his writing sessions, he would take walks through Madrid, observing daily life, eavesdropping on conversations, and gathering details that would enrich his novels. He was known to smoke leaf cigars incessantly but did not drink. His afternoons were dedicated to reading classics in Spanish, English, or French, including works by William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Miguel de Cervantes, Lope de Vega, and Euripides. In his later years, he developed a deep admiration for the works of Leo Tolstoy. His evenings often included more walks, unless there was a concert, as he was an ardent lover of music. He generally went to bed early and rarely attended the theater.

According to the writer Ramón Pérez de Ayala, Pérez Galdós dressed casually and favored somber tones to remain inconspicuous. In winter, he would often wear a white woolen scarf wrapped around his neck, with a half-smoked cigar in hand. When seated, his German shepherd dog would typically be by his side. He was in the habit of keeping his hair cropped "al rape" and reportedly suffered from severe migraines.

2.3.1. National Episodes

Following his early successes, Pérez Galdós conceived and developed the outline for his monumental project, the Episodios Nacionales (National Episodes). This ambitious series of historical novels aimed to chronicle major events in Spanish history, beginning with the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The first volume, titled Trafalgar, was published in 1873. Subsequent volumes appeared at irregular intervals until the forty-sixth and final novel, Cánovas, was released in 1912.

These historical novels were commercially successful and became a cornerstone of Pérez Galdós' contemporary reputation and income. He conducted meticulous research for these stories, often seeking out survivors and eyewitnesses to historical events to ensure balance and broader perspectives. For instance, in Trafalgar, he interviewed an old man who had served as a cabin boy aboard the ship Santísima Trinidad at the Battle of Trafalgar, and this individual became the central figure of the novel. Pérez Galdós frequently adopted a critical stance towards the official versions of events he described, which often led to conflicts with the Catholic Church, a dominant force in Spanish cultural life at the time.

The Mexican-Spanish writer Max Aub profoundly praised the series, stating that if all other historical material from the 19th century were lost, Galdós' work alone would suffice to capture "the complete, alive, real life of the nation during the hundred years that covered the author's claw." Aub further highlighted that Galdós had created hundreds of historical and imagined characters, equally true, achieving a feat comparable only to the greatest authors in the world, such as Tolstoy, in bringing forth the genius of their homeland through its struggles, glories, and misfortunes. He concluded that Galdós contributed more to the understanding of Spain by Spaniards than all historians combined.

2.3.2. Contemporary and Later Novels

Beyond the Episodios Nacionales, literary critic José Fernández Montesinos categorized Pérez Galdós' other novels into distinct groups.

The first group comprises his early works, from La Fontana de Oro up to La familia de León Roch (1878). Among these, Doña Perfecta (1876) is particularly well-known, illustrating the profound impact of a young radical's arrival in a stiflingly clerical town. In Marianela (1878), Galdós explores themes of perception and rejection as a young man regains his eyesight only to reject his best friend, Marianela, due to her perceived ugliness.

The second and most significant group, known as the Novelas españolas contemporáneas (Contemporary Spanish Novels), spans from La desheredada (The Disinherited Woman) (1881) to Ángel Guerra (1891). This loosely related series of 22 novels represents his major claim to literary distinction and includes his masterpiece, Fortunata y Jacinta (1886-87). These novels are interconnected through the device of recurring characters, a technique borrowed from Balzac's La Comédie humaine. Fortunata y Jacinta is a sprawling work, nearly as long as Tolstoy's War and Peace, which follows the fortunes of four central characters: a young man-about-town, his wife, his lower-class mistress, and her husband. The character of Fortunata was inspired by a real girl Pérez Galdós observed in a Madrid tenement building, drinking a raw egg, a scene that directly informs the fictional characters' initial encounter. In Miau (1888), Galdós portrays a proud family losing their livelihood after the father, a middle-aged civil servant, loses his job due to a government change, eventually leading him to suicide. Ángel Guerra (1891) tells the story of an unbalanced man's attempts to win the affections of a pious and unapproachable woman, transitioning from agnosticism to Catholicism in the process.

The third category consists of his later novels, characterized by psychological investigation. Many of these works employ a dialogue form, signifying an evolution in his narrative technique towards a more direct exploration of character interiority.

2.3.3. Plays

Pérez Galdós ventured into dramatic writing, returning to the theater with adaptations of his novels and original plays that often stirred public debate. His first mature play, Realidad (Reality), was an adaptation of his novel of the same name, which had already been written in dialogue form. Pérez Galdós was drawn to the immediate feedback of direct contact with the public. Rehearsals for Realidad began in February 1892, and the opening night saw a packed theater and enthusiastic reception. However, the play did not receive universal critical acclaim. Its realism, particularly in dialogue, deviated from the theatrical norms of the era, and its depiction of a scene in a courtesan's boudoir and an "un-Spanish" attitude towards a wife's adultery provoked controversy. The Catholic press notably denounced the author as a perverse and wicked influence. Despite the controversy, the play ran for twenty nights.

In 1901, his play Electra caused a significant uproar, matched by equally hyperbolic enthusiasm from its supporters. As with many of his works, Pérez Galdós used Electra to target clericalism and the "inhuman fanaticism and superstition" he believed could accompany it. Performances were frequently interrupted by audience reactions, and Galdós had to make numerous curtain calls. After the third night, conservative and clerical factions organized a demonstration outside the theater, leading to clashes with the police and the arrest of two members of a workers' organization who had opposed the demonstration. Several people were wounded in the confrontation. The next day, newspapers were sharply divided, with liberal publications supporting the play and Catholic/conservative ones condemning it. Electra saw over one hundred performances in Madrid alone and was also staged in the provinces. A revival in Madrid 33 years later, in 1934, generated a similar degree of uproar and outrage.

2.4. Influences and Literary Style

Pérez Galdós's extensive travels profoundly influenced his writing, providing him with a detailed knowledge of numerous cities, towns, and villages across Spain, which he incorporated into his novels, such as Toledo in Ángel Guerra. He also visited Great Britain on multiple occasions, with his first trip occurring in 1883. His vivid descriptions of various districts and the "low-life" characters he encountered in Madrid, particularly in Fortunata y Jacinta, bear resemblances to the narrative approaches of Dickens and French Realist novelists like Balzac.

Pérez Galdós also demonstrated a keen interest in technology and crafts. This is evident in his detailed descriptions, such as the lengthy accounts of ropery in La desheredada or the meticulous explanations of how the heroine of La de Bringas (1884) created her pictures from hair. He was also influenced by Émile Zola and Naturalism, a literary movement where writers aimed to illustrate how their characters were shaped by the interplay of heredity, environment, and social conditions. This set of influences is perhaps most apparent in Lo prohibido (The Forbidden) (1884-85), which is also notable for its first-person narration by an unreliable narrator who dies during the course of the work, a technique that predates similar experiments by authors like André Gide in works such as L'immoraliste.

Furthermore, Pérez Galdós was influenced by the philosopher Karl Christian Friedrich Krause, whose ideas were popularized in Spain through the educationalist Francisco Giner de los Ríos. An example of this influence can be found in his novel El Amigo Manso (Our Friend Manso) (1882). The mystical tendencies of Krausism also led to his interest in the wisdom sometimes exhibited by individuals perceived as mad. This theme becomes significant in Pérez Galdós' works from Fortunata y Jacinta onward, appearing in novels such as Miau (1888) and his final novel, La razón de la sinrazón (The Reason of Unreason).

Throughout his literary career, Pérez Galdós frequently drew the ire of the Catholic press. His critiques were directed at what he perceived as abuses of entrenched and dogmatic religious power, rather than at religious faith or Christianity itself. In fact, the need for faith is a very important feature in many of his novels, and he often presented sympathetic portraits of priests and nuns.

2.5. Political Involvement

Despite his strong attacks on conservative forces, Pérez Galdós initially showed only limited interest in direct political involvement. However, in 1886, then-Prime Minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta appointed him as the (absentee) deputy for the town and district of Guayama, Puerto Rico at the Madrid parliament. Although he never visited Puerto Rico, he ensured his representative kept him informed of the area's status and felt a duty to properly represent its inhabitants. This appointment lasted for five years and primarily provided him with a firsthand opportunity to observe the conduct of politics, which he later incorporated into scenes in some of his novels.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pérez Galdós deepened his political engagement. In 1907, he was elected as a representative in the Cortes. In 1909, alongside Pablo Iglesias Posse, he led the Republican-Socialist Conjunction, a significant political alliance. However, Pérez Galdós, who stated he "did not feel himself a politician," soon withdrew from the daily political struggles, which he described as "for the minutes and the farce," preferring to dedicate his already diminishing energies to his novel and theater work. In 1914, he was again elected as a republican deputy for Las Palmas. This election coincided with a national tribute to Pérez Galdós, organized in March 1914, by a board composed of prominent figures such as Eduardo Dato (head of government), banker Gustavo Bauer (representing Rothschild & Co), Melquiades Álvarez (leader of the reformists), and the Duke of Alba, as well as writers including Jacinto Benavente and José Echegaray. Notably, politicians such as Antonio Maura or Alejandro Lerroux were not included, nor were representatives of the Church or the socialists.

In 1918, he joined Miguel de Unamuno and Mariano de Cavia in a protest against the encroaching censorship and authoritarianism emanating from the monarch. His critical perspective on the Spanish political system, particularly the two dominant parties, was sharply articulated in one of his last Episodios Nacionales, Cánovas (1912). In this work, he expressed a profound pessimism for Spain's destiny, stating: "The two parties that have agreed to take turns peacefully in power are two herds of men who aspire only to graze on the budget. They lack ideals, no lofty goal moves them, they will not improve in the least the living conditions of this unhappy, very poor and illiterate race. They will pass one after the other, leaving everything as it is today, and they will lead Spain to a state of consumption that, for sure, will end in death. They will tackle neither the religious problem, nor the economic problem, nor the educational problem; they will do nothing but pure bureaucracy, caciquism, sterile work of recommendations, favors to cronies, legislating without any practical efficacy, and on with the little lanterns..." This excerpt underscores his disillusionment with the political establishment and his advocacy for deeper societal change.

2.6. Later Life and Death

Pérez Galdós faced significant personal challenges in his later years. He began to lose his eyesight in 1912, eventually becoming completely blind. This period was also marked by increasing financial difficulties and persistent illness. Despite these hardships, he continued to dictate his books for the rest of his life.

From 1912 to 1916, Pérez Galdós was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature for five consecutive years. However, he was never successful, largely due to a boycott by conservative and traditionalist Catholic sectors of Spanish society who opposed his anti-clerical views and refused to recognize his literary merit. Among his nominators was José Echegaray, a Nobel laureate from 1904.

To address his financial struggles, a national board tribute was established in March 1914, with the King and Prime Minister Romanones being among the first subscribers. However, the outbreak of World War I led to the scheme's closure in 1916, with the money raised falling short of half his required debts. In the same year, the Ministry of Public Instruction appointed him to manage arrangements for the Cervantes tercentenary, providing a stipend of 1.00 K ESP per month. Although the event never took place, this stipend continued for the remainder of Pérez Galdós's life, offering some financial stability.

In 1897, prior to his health decline, Pérez Galdós was elected to the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy), a prestigious recognition of his literary standing. His admiration for Tolstoy's work influenced a certain spiritualism in his final writings, coupled with a deep pessimism for Spain's future, as reflected in Cánovas.

Benito Pérez Galdós died on January 4, 1920, at the age of 76. Shortly before his death, a statue honoring him, funded solely by public donations, was unveiled in the Parque del Buen Retiro, Madrid's most popular park. Pérez Galdós, by then blind, attended the ceremony. He explored the statue's face with his hands and, upon recognizing it, reportedly wept and told the sculptor, a close friend, "Magnificent, my friend Macho, and how it looks like me!"

3. Themes and Social Commentary

Pérez Galdós's works are rich with recurring themes and incisive social commentary, reflecting his keen observation of Spanish society and his progressive worldview.

3.1. Anti-clericalism and Critique of Conservative Power

A consistent and defining feature of Pérez Galdós's literary output is his robust criticism of the abuses of religious authority and the entrenched power of conservative forces in Spanish society. He meticulously depicted how dogmatic religious power and clericalism could foster "inhuman fanaticism and superstition," often portraying the detrimental impact of these forces on individuals and communities. This theme is particularly prominent in works like Doña Perfecta, where the arrival of a liberal young man exposes the oppressive and suffocating nature of a clerical town, and Electra, which directly targeted clericalism and its societal consequences, leading to widespread public controversy.

It is important to note that Galdós's criticism was directed at the institutional and political abuses of religion rather than religious faith or Christianity per se. Indeed, the necessity of faith is a significant feature in many of his novels, and he often presented sympathetic portraits of individual priests and nuns, distinguishing between genuine spirituality and its corrupt institutional manifestations. His critique underscored his commitment to liberal ideals and social progress, challenging the dominant conservative and religious establishment of 19th-century Spain.

3.2. Portrayal of Spanish Society and Human Condition

Pérez Galdós was renowned for his nuanced and realistic depiction of various social classes and the intricate complexities of the human experience in 19th-century Spain. He possessed a remarkable ability to delve into psychological depth, exploring the individual struggles and inner lives of his characters within the broader constraints of their societal environments.

His masterpiece, Fortunata y Jacinta, offers a comprehensive and multi-layered portrayal of Madrid society, with its two female protagonists symbolizing distinct social strata: Fortunata representing the working class and Jacinta the bourgeoisie. Through their intertwined lives and tragic fates, Galdós provides a symbolic commentary on the limitations of the 1868 Spanish revolution, suggesting that its failure stemmed from the inability of the bourgeois-led movement to genuinely connect with and integrate the popular classes.

In other works, such as Miau, he critically examines the "vanity of the middle class and the fear of poverty," demonstrating how societal pressures and economic precarity could lead to individual despair and destructive behaviors. Galdós's meticulous observation, which allowed him to accurately remember and recreate scenes and dialogue, contributed to the vivid and authentic feel of his narratives, making the reader feel as if the stories unfold before their eyes. His novels thus serve not only as compelling narratives but also as invaluable social documents, offering deep insights into the moral, social, and political fabric of his era.

4. Legacy and Critical Reception

Benito Pérez Galdós left an indelible mark on Spanish literature, his enduring influence and standing among critics and the public solidifying his position as a literary giant.

4.1. Literary Significance

Pérez Galdós made profound contributions to Spanish realism, elevating the genre to new heights with his intricate plots, detailed character development, and comprehensive portrayal of societal dynamics. His narrative techniques, characterized by meticulous observation, psychological depth, and the use of recurring characters, have had a lasting influence on subsequent generations of Spanish writers.

Internationally, he is frequently compared to major European novelists of his time, including Charles Dickens, Honoré de Balzac, and Leo Tolstoy, underscoring his stature as a novelist of universal appeal and significance. His ability to weave together historical events with fictional narratives, as seen in his Episodios Nacionales, and to explore complex social and psychological themes in his contemporary novels, marks him as a master storyteller who captured the essence of his nation's history and its people's spirit.

4.2. Public and Academic Assessment

Benito Pérez Galdós has consistently remained highly popular in Spain, where he is often considered second only to Miguel de Cervantes in literary eminence. Scholars and enthusiasts of his work are known as "Galdosistas," a testament to the dedicated study and admiration his oeuvre inspires. His widespread recognition within Spain was symbolically reflected by his image appearing on the now-defunct 1,000 peseta banknote, a distinction reserved for figures of immense national importance.

Despite his immense popularity and critical acclaim within Spain, his recognition in Anglophone countries was slower to develop, with only a few of his works translated into English before the mid-20th century. However, his popularity has gradually increased in the English-speaking world over time, with more translations becoming available.

Academically, Pérez Galdós is celebrated for his encyclopedic depiction of 19th-century Spain, his innovative narrative structures, and his engagement with progressive social ideas. While generally lauded, his works and political leanings did provoke criticism, particularly from conservative and Catholic circles during his lifetime, which notably contributed to him not receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature despite multiple nominations. This opposition stemmed from his perceived "left-wing ideological bias" and anti-clerical stance. Despite these controversies, he is widely regarded as the "giant of modern Spanish literature," whose powerful observational skills and detailed memory allowed him to craft narratives that truly reflected his era.

5. Adaptations and Tributes

The enduring popularity and significance of Benito Pérez Galdós's works have led to numerous adaptations across various media and numerous tributes commemorating his legacy.

5.1. Film and Other Adaptations

Many of Pérez Galdós's novels have been adapted into cinematic works, demonstrating the lasting appeal and versatility of his narratives. Notable film adaptations include:

- Beauty in Chains (originally Doña Perfecta), directed by Elsie Jane Wilson in 1918.

- Luis Buñuel directed three significant adaptations:

- Viridiana (1961), which, though not explicitly stated by Buñuel, is based upon Galdós's novel Halma.

- Nazarín (1959).

- Tristana (1970).

- La Duda (The Doubt) was filmed in 1972 by Rafael Gil.

- El Abuelo (The Grandfather), directed by José Luis Garci in 1998, received international release a year later. This novel had been previously adapted into an Argentine film, also titled El Abuelo, in 1954.

- In 2018, Sri Lankan director Bennett Rathnayke directed the film adaptation Nela.

5.2. Memorials and Cultural Heritage

q=Casa-Museo Pérez Galdós, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria|position=left

The primary memorial dedicated to Benito Pérez Galdós is the **Pérez Galdós Museum** (Casa-Museo Pérez GaldósSpanish), located in Triana, in the center of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. This museum is housed in the very building where Pérez Galdós was born. The house was acquired in 1954 by the Cabildo de Gran Canaria (the insular government of Gran Canaria) and inaugurated on July 9, 1960, by María Pérez Galdós Cobián, the writer's daughter.

Visitors to the museum can explore the house where the writer grew up, offering a tangible connection to his early life. The museum features a comprehensive display of documents, furniture, musical instruments, paintings, and photographs that belonged to Pérez Galdós and his family, providing insights into his personal and intellectual world. The museum's core mission is the conservation, study, and dissemination of Pérez Galdós's legacy. To this end, its management has actively supported international congresses, conferences, and exhibitions related to the author and has developed a publishing line. The museum also houses a specialized library containing numerous works by Pérez Galdós in various languages, alongside a complete collection of his writings.

Another significant tribute to Pérez Galdós is the **Monument to Galdós** located in the Parque del Buen Retiro, Madrid's most popular park. This statue, a testament to his national prominence, was financed solely by public donations and was unveiled shortly before his death in 1920.

6. Works

Benito Pérez Galdós was a prolific writer, producing an extensive body of work across several genres.

6.1. Novels

- La Fontana de Oro (1870)

- La Sombra (1871)

- El Audaz (1871)

- Doña Perfecta (1876)

- Gloria (1877)

- Marianela (1878)

- La familia de León Roch (1878)

- La desheredada (1881)

- El Amigo Manso (1882)

- El Doctor Centeno (1883)

- Tormento (1884)

- La de Bringas (1884)

- Lo prohibido (1884-85)

- Fortunata y Jacinta (1886-87)

- Celín, Tropiquillos y Theros (1887)

- Miau (1888)

- La Incógnita (1889)

- Torquemada en la Hoguera (1889)

- Realidad (1889)

- Ángel Guerra (1891)

- Tristana (1892)

- Torquemada en la Cruz (1893)

- La Loca de la Casa (1893)

- Torquemada en el Purgatorio (1894)

- Torquemada y San Pedro (1895)

- Nazarín (1895)

- Halma (1895)

- Misericordia (1897)

- El Abuelo (1897)

- Casandra (1905)

- El Caballero Encantado (1909)

- La Razón de la Sinrazón (1915)

6.2. Episodios Nacionales

Pérez Galdós's monumental series of historical novels includes 46 volumes across five series:

- First Series**

- Second Series**

- Third Series**

- Fourth Series**

- Fifth Series**

6.3. Plays

- Quien Mal Hace, Bien no Espere (1861, lost)

- La Expulsión de los Moriscos (1865, lost)

- Un Joven de Provecho (1867?, published in 1936)

- Realidad (1892)

- La Loca de la Casa (1893)

- Gerona (1893)

- La de San Quintín (1894)

- Los Condenados (1895)

- Voluntad (1896)

- Doña Perfecta (1896)

- La Fiera (1897)

- Electra (1901)

- Alma y Vida (1902)

- Mariucha (1903)

- El Abuelo (1904)

- Barbara (1905)

- Amor y Ciencia (1905)

- Pedro Minio (1908)

- Zaragoza (1908)

- Casandra (1910)

- Celia en los Infiernos (1913)

- Alceste (1914)

- Sor Simona (1915)

- El Tacaño Salomón (1916)

- Santa Juana de Castilla (1918)

- Antón Caballero (1922, unfinished)

6.4. Short Stories and Other Writings

- Una industria que vive de la muerte. Episodio musical del cólera (1865)

- Necrología de un proto-tipo (1866)

- La conjuración de las palabras. Cuento alegórico (1868)

- El artículo de fondo (1871)

- La mujer del filósofo (1871)

- La novela en el tranvía (1871)

- Un tribunal literario (1872)

- Aquél (1872)

- La pluma en el viento o el viaje de la pluma (1873)

- En un jardín (1876)

- La mula y el buey (1876)

- El verano (1876)

- La princesa y el granuja (1877)

- El mes de junio (1878)

- Theros (1883)

- La tienda-asilo (1886)

- Celín (1889)

- Tropiquillos (1893)

- El Pórtico de la Gloria (1896)

- Rompecabezas (1897)

- Rura (1901)

- Entre copas (1902)

- La república de las letras (1905)

- Crónicas de Portugal (1890)

- Discurso de Ingreso en la Real Academia Española (1897)

- Memoranda, Artículos y Cuentos (1906)

- Política Española I (1923)

- Política Española II (1923)

- Arte y Crítica (1923)

- Fisonomías Sociales (1923)

- Nuestro Teatro (1923)

- Cronicón 1883 a 1886 (1924)

- Toledo. Su historia y su Leyenda (1927)

- Viajes y Fantasías (1929)

- Memorias (1930)

7. Works in English Translation

Many of Benito Pérez Galdós's original works have been translated into English, making his extensive literary output accessible to a wider audience.

7.1. Novels

- Gloria (1879, translated by Natham Wetherell; 1883, translated by Clara Bell; 2012, translated by N. Wetherell)

- Doña Perfecta, a tale of Modern Spain (1886, translated by D. P. W.; 1884, translated by Clara Bell; 1883, translated by D. P. W.; 1885, translated by Mary jane Serrano; 1940; 1960, translated by Harriet de Onís; 1999, translated by A. K. Tulloch; 2009, translated by Graham Whittaker; 2013, translated by D. P. W.; 2009, 2014)

- Marianela (1893, translated by Mary Wharton; 1883, translated by Clara Bell; 1892, translated by Hellen W. Lester; 2013; 2015, translated by Mary Wharton)

- La familia de León Roch (1888, translated by Clara Bell; 1974, translated by Clara Bell; 2018)

- The Spendthrifts (original title La de Bringas) (1951, translated by Gamel Woolsey; 1953, translated by Gamel Woolsey; 1952, translated by Gamel Woolsley; 2013)

- Torment (original title Tormento) (1952, translated by J. M. Cohen; 1998, translated by Abigail Lee Six)

- Miau (1963, translated by J. M. Cohen; 1970, translated by Eduard R. Mulvihill, Roberto G. Sánchez)

- Fortunata and Jacinta: Two Stories of Married Women (original title Fortunata y Jacinta) (1973, translated by Lester Clarck; 1986, translated by Agnes Moncy Gullón; 1987, translated by Agnes Moncy Gullón; 1992, translated by Harriet S. Turner; 1998, translated by Agnes Moncy Gullón)

- La desheredada (1976, translated by Lester Clarck)

- Torquemada on the Fire (original title Torquemada en la hoguera) (1985, translated by Nicholas Round; 2004, translated by Stanley Appel Baum)

- Torquemada (1988, translated by Frances M. López-Morillas)

- Nazarín (1993, translated by Jo Labanyi; 1997, translated by Robert S. Ruder, Gloria Chacón de Arjona)

- Misericordia (1995, translated by Charles de Salis; 2007, translated by Robert H. Russell; 2013, translated by Robert H. Russell; 2017)

- That Bringas Woman: The Bringas Family (original title La de Bringas) (1996, translated by Catherine Jagoe)

- Tristana (1961, translated by R. Selden-Rose; 1996; 1998; 2014, translated by Margarte Jull Costa; 2016, translated by Pablo Valdivia)

- Halma (2015, translated by Robert S. Rudder, Ignacio López-Calvo; 2010)

- El amigo Manso (1963; 1987, translated by Robert Russell)

- The Shadow (original title La sombra) (1980, translated by Karen O. Austin)

- Torquemada novels: Torquemada at the Stake - Torquemada on the Cross - Torquemada in Purgatory - Torquemada and Saint Peter (original titles Torquemada en la hoguera. Torquemada en la Cruz. Torquemada en el Purgatorio. Torquemada y San Pedro) (1986, translated by Frances M. López-Morillas; 1996, translated by Robert G. Trimble)

- The Golden Fountain Café: a Historic Novel of the XIXth Century (original title La Fontana de Oro) (1989, translated by Walten Rubin et al.)

- Ángel Guerra (1990, translated by Karen O. Austin)

- The Unknown (original title La incógnita) (1991, translated by Karen O. Austin)

- Reality (original title Realidad) (1992, translated by Karen O. Austin)

- Compassion (original title Misericordia) (1962, translated by Toby Talbot)

7.2. Episodios Nacionales

- Trafalgar (1905, 1921, 1951, translated by Frederick Alexander Kirkpatrick; 1884, translated by Clara Bell; 1993; 2016)

- The Court of Charles IV. A Romance of the Escorial (original title La Corte de Carlos IV) (1886, translated by Clara Bell; 1993; 2009, translated by Clara Bell)

- La batalla de los Arapiles (1985, translated by R. Ogden)

- Saragossa. A History of Spanish Valor (original title Zaragoza) (1899, translated by Minna Caroline Smith; 2015, translated by Minna Smith)

- The Campaign of the Maestrazgo (original title La campaña del Maestrazgo) (1990, translated by Lila Wells Guzmán)

- Gerona (1993, translated by G. J. Racz; 20115)

- A Royalist Volunteer (original title Un voluntario realista) (translated by Lila Wells Guzmán)

- Juan Martin el Empecinado (2009)

- El Grande Oriente (2009)

- Aita Tettuaen (2009)

7.3. Plays

- The Grandfather. Drama in five acts (original title El abuelo) (1910, translated by Elizabeth Wallace; 2017)

- Electra (1911; 1919, translated by Charles Alfred Turrell)

- The Duchess of San Quintín, Daniela (original title La de San Quintín) (1928, translated by Eleanor Bontecou, P. M. Hayden, J. G. Underhill)

- Marianela (2014, adapted by Mark-Brian Sonna)

- The Duchess of San Quintín: a play in three acts (original title La de San Quintín) (2016, translated by Robert M. Fedorcheck)

- Meow. A Tragicomedy (original title Miau) (2014, translated by Ruth Katz Crispin)

7.4. Short Stories

- The Conspiracy of Words (original title La conjuración de las palabras) (2007, translated by Robert H. Russell)

8. Online Works

Many of Benito Pérez Galdós's works are available digitally through various online libraries, projects, and archives.

- His collected works are available on [https://es.wikisource.org/wiki/Autor:Benito_P%C3%A9rez_Gald%C3%B3s Spanish Wikisource].

- The [http://www.shef.ac.uk/gep/urey.html Pérez Galdós Editions Project] at the University of Sheffield provides scholarly electronic editions. Torquemada en la hoguera is available [https://www.dhi.ac.uk/galdos/ here].

- Works by Benito Pérez Galdós can be found on [https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/3821 Project Gutenberg].

- Digitized works by Pérez Galdós are available through the [https://archive.org/search.php?query=%22Benito+P%C3%A9rez+Gald%C3%B3s%22 Internet Archive].

- Audio recordings of his works are accessible via [https://librivox.org/author/5244 LibriVox].

- A search for works by Benito Pérez Galdós can be conducted on [https://www.google.com/search?q=inauthor%3A%22Benito+P%C3%A9rez+Gald%C3%B3s%22&gbv=2&tbm=bks&tbs=bkv%3Af&dpr%3D1.1 Google Books].

- The official website of the [http://www.casamuseoperezgaldos.com/ Pérez Galdós House Museum] in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria offers complete works in ePub format [http://www.casamuseoperezgaldos.com/es/obra-completa-en-epub here].

- An online library from the Canary Islands government also provides some of his works in English [https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/bibliotecavirtual/cgi-bin/opac/O7022/ID6b959d00?ACC=131&srch=%22Ingl%E9s%22.LENG.&xsface=on&etapaFace=3&fieldFace=LENG here].