1. Early Life and Background

Alessandro Farnese was born into the influential House of Farnese, a prominent Italian noble family with strong ties to the papacy and Spanish royalty. His upbringing and education prepared him for a life of military and political service.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Alessandro was born on 27 August 1545. His father was Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma, who was a grandson of Pope Paul III. His mother was Margaret of Austria, an illegitimate daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V. Alessandro had a twin brother named Carlo, who died in Rome on 7 October 1549, less than two months after his birth.

In 1550, Alessandro and his mother left Rome for Parma. When Margaret was appointed Governor of the Netherlands in 1556, Alessandro accompanied her to Brussels. He was then placed under the custody of Philip II of Spain to ensure the loyalty of the Farnese family to the Spanish crown. While in the King's care, he visited the English royal court. Subsequently, he moved to Spain, where he was raised and educated alongside his cousin, the ill-fated Don Carlos, and his half-uncle, Don Juan, both of whom were close to his age.

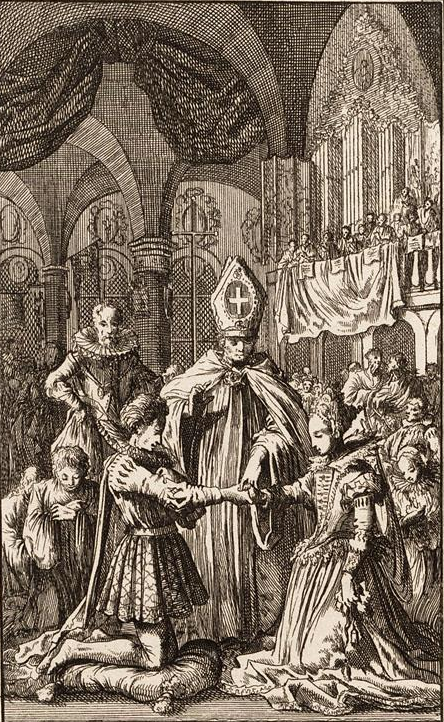

1.2. Marriage and Early Military Career

In 1565, Alessandro Farnese's marriage to Maria of Portugal was celebrated with great splendor in Brussels. This marriage marked the end of his period as a hostage of Philip II. Maria was known for her piety, deep affection for her husband, and extensive education. As the granddaughter of Manuel I, King of Portugal, she held significant influence at the court in Madrid.

Alessandro commanded three galleys during the Battle of Lepanto (1571) and participated in subsequent campaigns against the Turks. It would be seven years before he again had the opportunity to display his military talents on a large scale. During this interval, the provinces of the Netherlands had revolted against Spanish rule. Don Juan of Austria, who had been sent as governor-general to restore order, faced considerable difficulties in dealing with William the Silent, who had successfully united all the provinces in common resistance to King Philip II.

2. Governor-General of the Netherlands

q=Spanish Netherlands 1579|position=right

Alessandro Farnese's tenure as Governor-General of the Spanish Netherlands was a critical period in the Eighty Years' War. He employed a combination of astute military campaigns and skillful diplomatic strategies, which had profound socio-political consequences for the region.

2.1. Appointment and the Dutch Revolt

In the autumn of 1577, shortly after his wife's death, Farnese led Spanish reinforcements from Italy along the Spanish Road to join Don Juan of Austria in the Netherlands. His able strategy and prompt decision at a critical moment were decisive in winning the Battle of Gembloux (1578) in early 1578, where the Dutch forces were defeated. Shortly after this victory, the Siege of Zichem took place, during which the garrison was massacred and the town was sacked. This incident remains a significant stain on Farnese's otherwise acclaimed career. This was followed by the five-day Siege of Nivelles in March 1578, where the citizens quickly capitulated, influenced by the fate of Zichem. That summer, Farnese managed to prevent the Spanish defeat at the Battle of Rijmenam (1578) from being decisive.

In October 1578, Don Juan, whose health had deteriorated, died. Philip II appointed Farnese to succeed him as Captain-General of the Army of Flanders. Initially, Philip also appointed Farnese's mother, Margaret, as co-Governor-General. However, Alessandro found this arrangement unacceptable, demanding to hold both titles of Captain-General and Governor-General, threatening to resign otherwise and leave military matters entirely to Margaret. Philip eventually conceded, and after four years, Margaret returned to Parma, leaving Alessandro as the sole Governor-General.

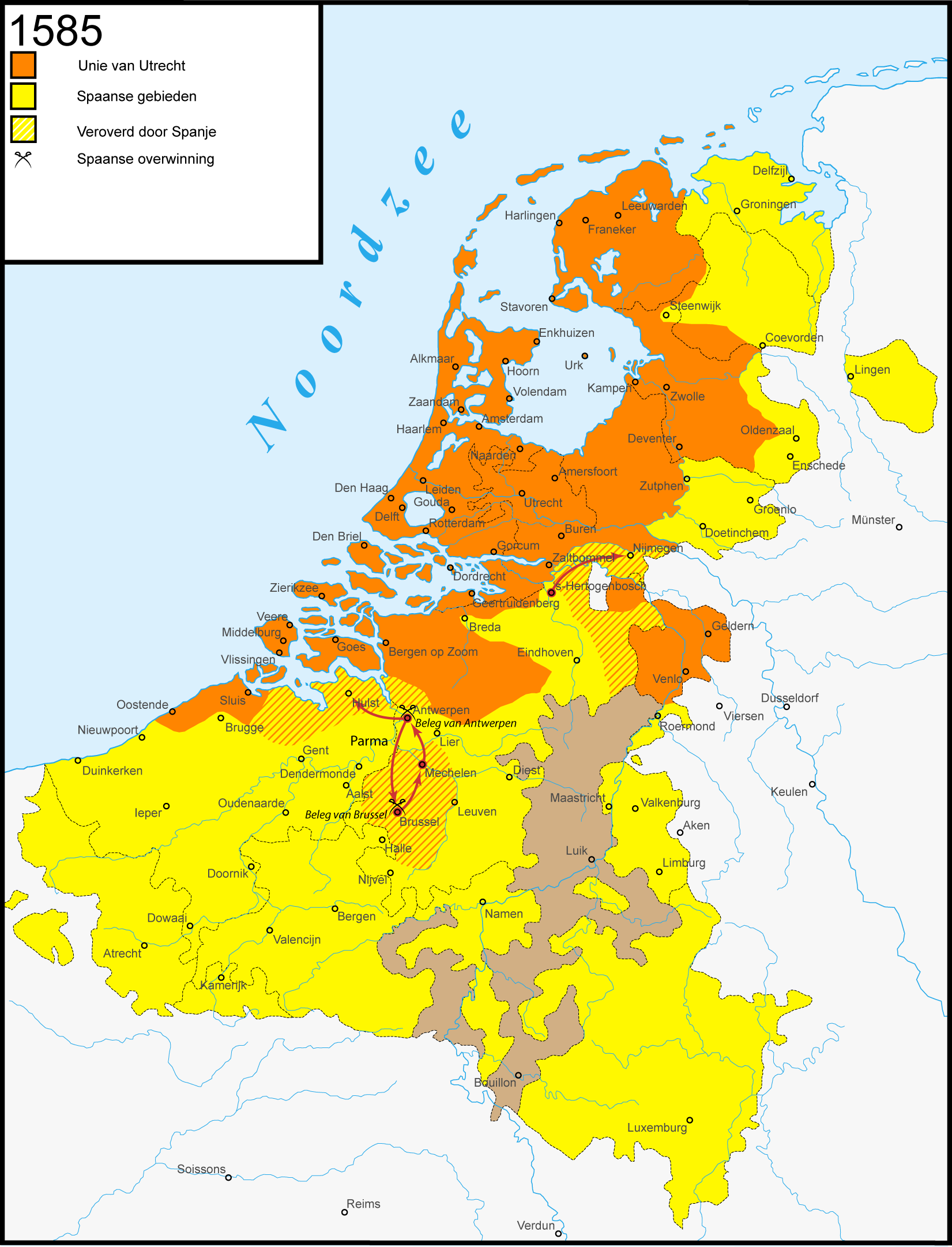

2.2. Diplomatic Strategy and the Union of Arras

Upon Don Juan's death, Farnese was confronted with a complex situation in the Netherlands, where his opponents were deeply divided along religious (Catholic and Protestant) and regional (Fleming and Walloon) lines. He skillfully exploited these divisions to his advantage. Through the Treaty of Arras, signed in January 1579, he secured the support of the "Malcontents," the Catholic nobles of the southern (Walloon) provinces, for the royal cause. This diplomatic success regained the allegiance of these provinces for the Spanish king. In response, the rebels in the seven northern provinces formed the Union of Utrecht, formally renouncing Philip's rule and pledging to fight to the end for their independence.

2.3. Major Sieges and Military Campaigns

Once he had secured a base of operations in Hainaut and Artois, Farnese earnestly began the task of reconquering Brabant and Flanders by force. His strategy involved offering generous terms for surrender: no massacres or looting, retention of historic urban privileges, full pardon and amnesty, and a gradual return to the Catholic Church.

He commenced the Siege of Maastricht (1579) on 12 March 1579. Farnese ordered his troops to sap the city walls, while the inhabitants of Maastricht dug counter-tunnels. Hundreds of Spanish soldiers died in underground fighting, some from boiling oil poured into their tunnels, others from lack of oxygen when Dutch defenders ignited fires. An additional 500 Spanish soldiers died when a mine they intended to use exploded prematurely. On the night of 29 June, Farnese's men managed to enter the city while the exhausted defenders slept. As the city had not surrendered after the walls were breached, the laws of warfare in the 16th century permitted the victors to loot the conquered city. The Spanish forces plundered Maastricht for three days, resulting in many civilian deaths. The looting was particularly violent, possibly exacerbated by Farnese being bedridden with a fever during this period.

In adherence to the Treaty of Arras, the Spanish troops were temporarily expelled from the country, leaving Alexander with only Walloon troops for the Siege of Tournai (1581). The difficulties encountered with these less disciplined forces during the siege helped convince the Walloon lords to allow the return of foreign, and more importantly, Spanish troops.

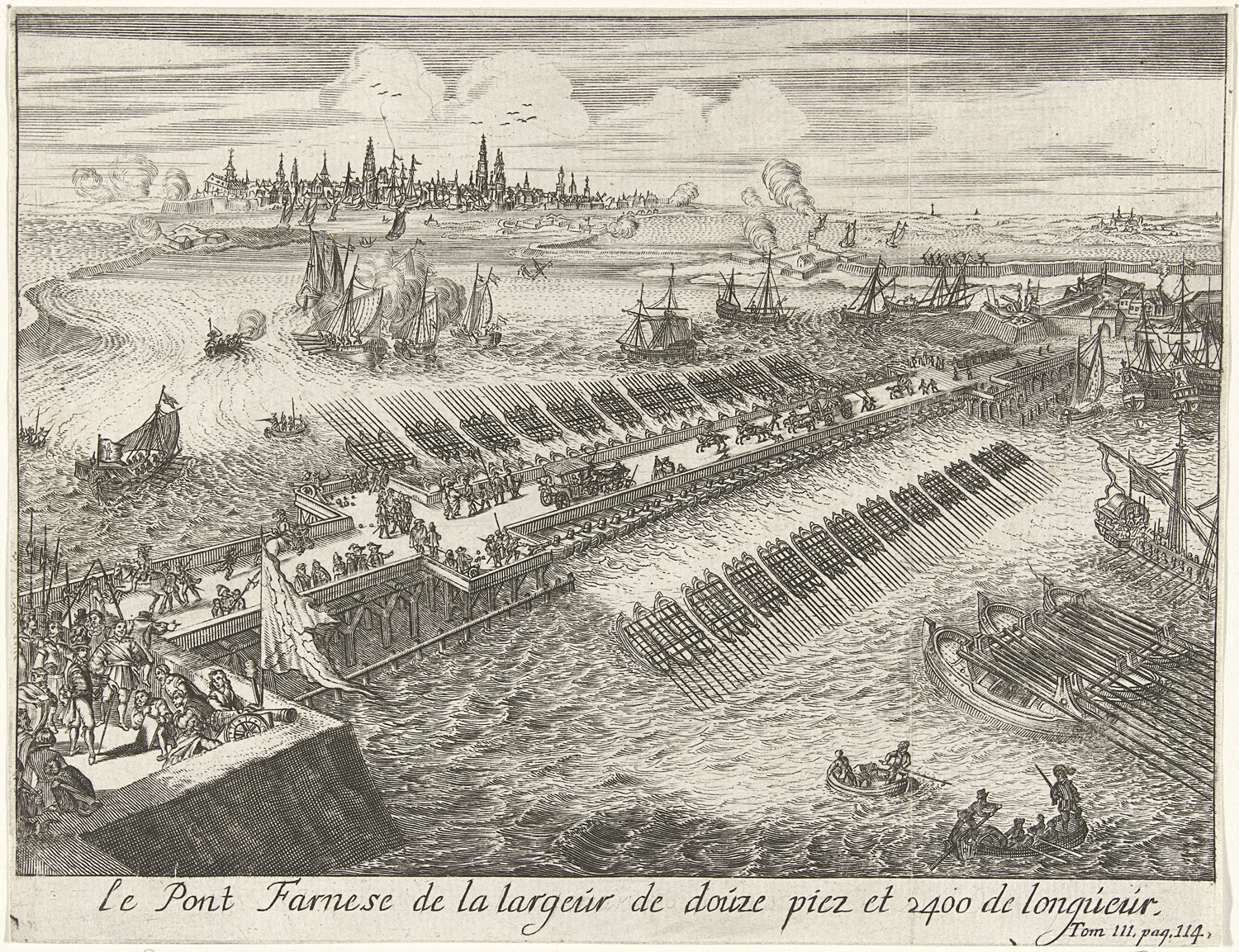

The apex of Alexander Farnese's military career was the siege of the great seaport of Antwerp. The city was open to the sea, strongly fortified, and defended with resolute determination by its citizens, led by Marnix van St. Aldegonde and assisted by the ingenious Italian engineer Federigo Giambelli. The siege began in 1584 and demanded all of Farnese's military genius. He successfully cut off all sea access to Antwerp by constructing a bridge of boats across the Scheldt from Kallo to Oordam, despite desperate efforts by the besieged townspeople. The terms offered for surrender included a clause requiring all Protestants to leave the city within four years. This disciplined capture and occupation of Antwerp should not be confused with the bloody events of the Spanish Fury on 4 November 1576; Farnese consciously avoided the mistakes of his predecessors. With the fall of Antwerp, and with Mechelen and Brussels already under Farnese's control, the entirety of the southern Netherlands was once more placed under the authority of Philip II. Only Holland and Zeeland, whose geographical position made them unassailable except by water, remained difficult to conquer.

Alexander pressed operations in the regions of the Meuse and the Rhine to maintain trade with Germany and prepare a gateway for conquering Holland and Zeeland. However, Philip II's parsimonious disbursement of funds began to negatively impact campaigns following Antwerp's conquest. The first notable Spanish defeat under Farnese's command occurred during his initial attempt to take control of Grave. In December 1585, facing a growing food shortage, Farnese marched his troops towards the Rhine and Meuse regions to relieve the burden of feeding them from Flanders, Brabant, and the Walloon provinces, while also undertaking operations to secure trade along those rivers. That winter was nearly disastrous for Farnese's army, saved only by the ""Miracle of Empel"." Nevertheless, by 7 June, the Siege of Grave (1586) was a fait accompli. Fortunately for Alexander, who became Duke upon his father's death in 1586, the poorly supplied English forces, sent by Elizabeth I, were defeated by his troops. The Siege of Sluis (1587) was necessary to secure a safe harbor for the Armada ships and proved successful.

2.4. Reconquest of the Southern Netherlands

Farnese's campaigns were largely successful in bringing the southern provinces of the Netherlands back under Spanish control. His strategic approach, combining military pressure with diplomatic overtures, effectively divided the rebel forces and secured the allegiance of the Catholic-majority southern regions. This reconquest established a clear cultural and religious separation between the northern and southern Netherlands, a division that would later significantly influence the formation of modern Belgium.

2.5. Challenges and Limitations

Despite his military successes, Farnese faced numerous challenges and limitations during his governorship. Financial constraints imposed by Philip II's parsimony frequently led to troop mutinies and shortages of supplies, hampering his ability to sustain continuous campaigns. The northern provinces, united by the Union of Utrecht, maintained persistent resistance, proving difficult to conquer due to their strong defenses and geographical advantages. Furthermore, Farnese's efforts in the Netherlands were repeatedly interrupted by Philip II's demands for intervention in France, which diverted crucial resources and troops away from the Dutch front, allowing the northern rebels to regain momentum.

3. Spanish Armada Operation

Alessandro Farnese's role in the planning and execution of the Spanish Armada against England was a significant, albeit ultimately unsuccessful, chapter in his career.

When Alexander Farnese became Duke of Parma upon his father's death, he never formally ruled his duchy, instead naming his son Ranuccio as regent. He applied for leave to visit his paternal territory, but Philip II denied it, citing the lack of a suitable replacement in the Netherlands. While retaining Farnese in his command at the head of a formidable army, the king did not sanction his general's desire to use it for the conquest of England, which was at the time a supporter of the Dutch rebels.

Although Farnese was not enthusiastic about the English invasion project, in November 1583, he initially believed it possible to successfully invade England from the Netherlands with a force of 30,000 troops, relying mainly on the hope of a native Catholic insurrection. However, he emphasized to Philip II that three imperative conditions must be met: absolute secrecy, secure possession and defense of the Dutch provinces, and prevention of French interference through peace agreements or by sowing division among Huguenots and Catholics. Philip overruled him and instead solicited Marquis of Santa Cruz to draft an invasion plan that evolved into the Enterprise of England, commonly known as the Spanish Armada. As part of the general campaign preparations, Farnese moved against Ostend and Sluis, the latter of which was taken in August 1587.

The plan stipulated that Parma's troops would cross the English Channel in barges, protected by the Armada. Santa Cruz, appointed commander of the Armada, died in early 1588, and command was given to the less competent Duke of Medina Sidonia. The Armada entered the English Channel in the summer of that year, but poor communication between Parma and the Armada's commander made effective coordination difficult. Alexander informed Philip II that his barges were flat-bottomed transport vessels, not warships, and that he was being blockaded by English ships, preventing him from leaving Nieuwpoort and Dunkirk. Farnese expected the Armada to clear a passage for his barges. Parma's troops were also threatened by the presence of Dutch forces in flyboats, who aimed to destroy the barges and drown Parma's army at sea. In contrast, Medina Sidonia expected Parma to fight his way out of the ports and meet him in the channel. The English attack on the Armada in the Battle of Gravelines (1588), followed by an unfavorable change in wind direction, made a link-up impossible.

After the failure of the Armada, Farnese's fortunes seemed to decline. He broke up his camp in Dunkirk in September and sent the Marquis de Renty to the island of Tholen in preparation to besiege the predominantly English garrison at Bergen Op Zoom. Renty failed to capture Tholen, blaming bad weather, leading Farnese to express that he should have led the expedition personally. Nevertheless, on 19 September 1588, Alexander set out from Bruges with his army to besiege Bergen Op Zoom. After a six-week siege, with winter approaching, Parma abandoned the enterprise and withdrew to Brussels, sending his troops into winter quarters.

Alexander's final major victory in the Netherlands was the capture of Geertruidenberg, a strategic gateway to Holland. The English garrison there was in full revolt due to lack of pay. An English representative offered the city to Parma, and it was ultimately delivered to him on 9 April 1589.

4. Intervention in the French Wars of Religion

q=Paris, Rouen, Caudebec, Guise, Lagny-sur-Marne, Corbeil-Essonnes, Amiens|position=right

Alessandro Farnese's involvement in the French Wars of Religion diverted his attention and resources from the ongoing conflict in the Netherlands, impacting both theaters of war.

The Duke of Parma began experiencing the first effects of oedema after the failed siege of Bergen op Zoom. He had to travel to the town of Spa for nearly six months to treat his illness. During this time, the Old Tercio of Lombardy mutinied, and Farnese ordered its dissolution. Following this incident, Alexander's lieutenants suffered defeats in Friesland and Rheinberg.

4.1. Relief of Paris

Farnese intended to refocus his attention on the northern Netherlands, where the Dutch rebels had regrouped. However, on the night of 1-2 August 1589, Henry III of France was assassinated. Farnese was then ordered into France by Philip II to support the Duke of Mayenne and the Catholic opposition to the Protestant Henri de Navarre, also known as the "Béarnais." This diversion enabled the Dutch rebels to regain momentum in their revolt, which had been in ever deeper trouble since 1576. Parma had warned Philip II that the French incursion would endanger the gains made in the Netherlands and stated he would not accept responsibility for any losses or failures resulting from not heeding his advice.

Parma left Brussels on 6 August 1590 and arrived at Guise on 15 August. In late August, he moved to relieve Paris from the lengthy siege it had been placed under by Huguenots and Royalists loyal to Henry IV. Farnese's main goal was simply to resupply Paris by raising the blockade, not to annihilate Henry's army. When Henry learned of the approach of Mayenne and Farnese, he broke camp to actively engage in battle. Parma, however, had no intention of direct combat. He determined that capturing the fort at Lagny-sur-Marne would ensure traffic was maintained along the Marne River, which was still in the hands of the Catholic League. At dawn on 5 September, Lagny was bombarded and then stormed by Spanish troops, who put its 800-man garrison to the sword, all within sight of Henri's camp, a mere 7.5 mile (12 km) away. Henry abandoned the siege of Paris two days later but made one last unsuccessful attempt on 8-9 September. With the course of the Marne completely open to traffic, supplies flowed into Paris for the next several days.

Keeping Paris supplied required victuals from multiple sources. Most of Henry's forces occupied the areas along the Seine and Yonne rivers, so Parma decided to clear Corbeil to restore traffic on the Seine. The siege began on 22 September, and by 16 October, the town was taken. Its garrison was put to the sword, and the town was thoroughly sacked. With the siege of Paris lifted and its supply routes secured, Farnese began his return journey to the Netherlands on 3 November, where Maurice of Nassau had gone on the offensive. Alexander's withdrawal was not easy; he had thousands of men, wagons, and horses to move during foul weather, with the Béarnais harassing him the entire way. Anticipating these difficulties, the Duke arranged his columns in such a way that Henry could not rout him. Twenty days into the march, on 25 November near Amiens, Henry, with his cavalry, boldly charged Farnese's column only to be routed himself beyond the Aisne River and wounded during the retreat. One final unsuccessful skirmish took place on 29 November, with Henry within a few hundred paces of Farnese. Parma and Mayenne parted ways at Guise, and Alexander arrived in Brussels on 4 December 1590.

4.2. Siege of Rouen and Injury

Alexander Farnese had appointed Peter Ernst von Mansfeld as acting Governor-General while he was in France. Days after Farnese's departure for France, Mansfeld and Colonel Francisco Verdugo, operating in Friesland, began complaining to Philip II about the lack of money, supplies, and troop mutinies-all the issues Farnese had been raising for years. By the time Farnese returned, Maurice had regained Steenbergen, Roosendaal, Oosterhout, Turnhout, and Westerlo. Farnese's absence led to a reduction in Spanish military activity, allowing the Dutch time to reflect on effective policies against their enemy. This period marked the beginning of the Dutch Military Reforms, which eventually allowed them to achieve an even footing against the Spanish; Alexander had finally met his match in Maurice.

On the night of 24 July 1591, just days after engaging in the Siege of Knodsenburg, Alexander Farnese received orders from Philip II to abandon everything and return to France to aid the Catholic League. Realizing the difficulties of capturing the fort at Knodsenburg, he was actually relieved to honorably abandon an enterprise undertaken under unfavorable auspices. Before he could consider another expedition to aid the League, he needed to resume his treatments at Spa, where he arrived on 1 August with his son Ranuccio. In mid-November, Alexander drafted instructions for the interim Governor-General, Mansfeld again, and put measures in place for the defense of the Netherlands during his absence. By the end of November, the Duke was in Valenciennes, where he mustered his troops. Towards the middle of January 1592, Parma rendezvoused with Mayenne and made preparations to rescue Rouen from Henry.

Before heading to Rouen, Farnese made the strategic decision to capture Neufchâtel-en-Bray to keep supply lines open. Finally, on 20 April, Parma arrived a few miles from Rouen, where he was met by 50 cavalry sent by Villars. They informed him that Henry had lifted the siege and withdrawn towards Pont-de-l'Arche to entrench there; Rouen was saved. Rather than follow Farnese's advice to attack Henry's camp and destroy his forces, the League's leaders chose to capture Caudebec-en-Caux. During the siege, while reconnoitering the town, Farnese was severely wounded by a musket shot in his right forearm. The wound further undermined his already precarious health, forcing him to call his son Ranuccio to take command of the troops. Henry saw this as an opportunity to avenge the loss of Rouen. Instead of risking a full attack against the League's forces, he adopted a strategy from Farnese's own playbook, deciding to cut off all supply routes and starve them. The League's army abandoned Caudebec for Yvetot. The situation was worse than at Caudebec, and all the while, Farnese was seriously ill and mostly bed-ridden, yet still sharp in mind. The Duke of Parma finally devised a plan to clandestinely cross the Seine in boats, leaving just enough men to make Henry believe the entire army was still encamped. The Catholic army was across the river and long gone by the time Henry learned of it, literally right under his nose. After returning to the Netherlands, Alexander received a letter from Pope Clement VIII on 28 June, congratulating him "for rescuing the Catholic Army." Farnese quickly made his way back to Spa for yet more treatments.

5. Military Assessment and Legacy

Alessandro Farnese is widely regarded as one of the most brilliant military commanders and diplomats of the 16th century. His strategic capabilities and organizational skills were exceptional, allowing him to achieve significant successes in complex and challenging campaigns. However, his legacy is also marked by controversies and criticisms regarding the human cost of his military actions.

5.1. Reputation as a Commander and Diplomat

Farnese's talents as a commander, strategist, and organizer earned him the regard of contemporaries and historians as the greatest general of his age, as well as one of the best in history. He stood out for his equal proficiency in both warfare and diplomacy. Under his leadership, Philip II's army achieved the most comprehensive successes in the history of the Eighty Years' War, capturing more than thirty towns between 1581 and 1587 before being diverted from the Netherlands to the French theater. His campaigns gave Spain back permanent control of the southern provinces, establishing the cultural and religious separation which would eventually become the nation of Belgium.

5.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his acclaimed military genius, Farnese's career was not without criticism. The Siege of Zichem, where the garrison was put to the sword and the town sacked, is considered the biggest stain on his otherwise chivalrous career. Similarly, the three-day looting of Maastricht after its capture, which resulted in many civilian deaths, highlights the brutal realities of warfare under his command, even if he was ill at the time. These incidents underscore the significant human cost associated with his campaigns and the harsh consequences faced by civilian populations in conquered cities.

6. Personal Life and Family

Alessandro Farnese's personal life was intertwined with his public duties and family lineage.

From his marriage with Maria of Portugal, also known as Maria of Guimarães, he had three legitimate children:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Margherita Farnese | 7 November 1567 | 13 April 1643 | Married, 1581, Vincenzo I, Duke of Mantua; no issue. |

| Ranuccio Farnese | 28 March 1569 | 5 March 1622 | Succeeded as Duke of Parma; married, 1600, Margherita Aldobrandini; had issue. |

| Odoardo Farnese | 7 December 1573 | 21 February 1626 | Became a Cardinal. |

Alessandro Farnese also had an affair with Françoise de Renty, a young Flemish noblewoman known as "La Belle Franchine." An unpublished letter of instruction from Parma, contained in a manuscript at the Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, confirms the relationship, stating: "The Prince loves a lady of quality and is pleased when she is courted and served by those who esteem his favor..." While there is no definitive proof of children from this relationship, it is believed that Farnese arranged for and incentivized Count Jean-Charles de Gavre, a nobleman in Alessandro's household, to marry Françoise in 1586. Considering that the couple's first child, Marie-Alexandrine-Françoise de Gavre, was born soon afterwards in 1587, that her name (Alexandrine) is not found among either parent's ancestors, and the influence Françoise had over Farnese, it is quite possible that he was the child's biological father.

7. Death

Alessandro Farnese's final years were marked by declining health and political machinations that ultimately led to his removal from office, though he died before this order could be fully executed.

Ever since the failed Armada campaign against England, Spanish agents and courtiers in Philip II's court, who were jealous of Farnese's success, had engaged in a malicious campaign to discredit the Duke of Parma in the eyes of the king. After Farnese's return from his second French campaign, the king, who had always favored his nephew Alexander, allowed these complaints and accusations to influence his opinion. This change in sentiment caused the king to order the duke removed from his post in the Netherlands. The sovereign drafted a recall letter on 20 February 1592, while Farnese was marching on Rouen, and tasked Juan Pacheco de Toledo, II marqués de Cerralbo, to personally deliver it to the duke upon his return to Flanders. Cerralbo died along the way. The king then assigned Pedro Henriquez de Acevedo, Count of Fuentes to carry out this mission. The date of the recall letter was changed to 28 June 1592. Given Philip II's nature toward duplicitous intrigue, the king reassured Farnese that everything was fine, all the while arranging for his recall from Flanders. The duke knew nothing about these machinations and by October was feeling well enough to return to Brussels, only to learn that he was ordered to aid the League yet again.

Fully aware of his state of health, the Duke of Parma nevertheless prepared for this final campaign by arranging for loans and sumptuous quarters in Paris to project the appearance of a powerful representative of the King of Spain. He had written his last will and testament, repeatedly went to confession and took holy communion, and sent his son back to Parma so that, upon his death, the Farnesian States would not be deprived of a ruler.

The duke left Brussels on 11 November, arriving in Arras where, on 2 December 1592, he died at the age of 47. His mortal remains were dressed in a Capuchin habit, moved to Parma, and buried in the Capuchin church, next to his wife's tomb. Later, their mortal remains were moved to the crypt of the Basilica of the Madonna della Steccata, where they are still found today. His death spared him from seeing the provision by which he was relieved of the post of Governor-General. In January 2020, the Duke's remains were exhumed in an effort to clarify the circumstances of his death, which were ultimately determined to be pneumonia.

8. List of Battles and Operations

Alessandro Farnese participated in or commanded a significant number of battles, sieges, and military operations throughout his career.

Ottoman-Venetian War (1570-1573)

- Battle of Lepanto (1571)

- Battle of Koroni (1572)

- Siege of Navarino (1572)

Eighty Years' War

- Battle of Gembloux (1578)

- Siege of Zichem

- Siege of Nivelles

- Siege of Limbourg

- Capture of Dalhem

- Battle of Borgerhout

- Siege of Maastricht (1579)

- Siege of Cambrai (1581)

- Siege of Tournai (1581)

- Siege of Oudenaarde

- Siege of Lier (1582)

- Siege of Eindhoven (1583)

- Battle of Steenbergen (1583)

- Capture of Aalst (1584)

- Siege of Ghent (1583-1584)

- Siege of Brussels (1584-1585)

- Battle of Kouwensteinsedijk

- Fall of Antwerp

- Siege of Grave (1586)

- Siege of Venlo (1586)

- Destruction of Neuss

- Siege of Rheinberg (1586-1590)

- Battle of Zutphen

- Siege of Sluis (1587)

- Siege of Bergen op Zoom (1588)

- Capture of Geertruidenberg (1589)

- Siege of Knodsenburg

French Wars of Religion

- Siege of Paris (1590)

- Siege of Rouen (1591-1592)

- Siege of Caudebec