1. Biography

Abdus Salam's life was marked by intellectual brilliance from an early age, a deep commitment to scientific advancement, and a challenging relationship with his home country due to his religious beliefs.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Mohammad Abdus Salam was born on 29 January 1926, in Jhang, a small town in the Punjab Province of British India (now in Pakistan). He came from a Punjabi family belonging to the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, which had a strong tradition of learning and religious devotion. His father, Chaudhary Muhammad Hussain, was a school teacher in Jhang, and his mother was Hajirah, from Faizullah Chak near Batala. Salam's given name, Abd al-Salam, means "Servant of God," with "Abd" meaning servant and "Salam" being one of the 99 names of God in the Quran. He later added "Mohammad" to his name in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan.

Salam quickly gained a reputation for exceptional academic talent throughout Punjab. At the age of 14, he achieved the highest marks ever recorded for the entrance examination at the University of the Punjab. He received a full scholarship to the Government College University in Lahore. Initially, Salam was a versatile scholar with interests and excellence in both Urdu and English literature. However, he soon decided to focus on Mathematics. Despite his mentors encouraging him to become an English teacher, Salam pursued mathematics. As a fourth-year student, he published work on Srinivasa Ramanujan's mathematical problems and earned his B.A. in Mathematics in 1944.

His father wished for him to join the Indian Civil Service (ICS), which was the highest aspiration for university graduates at the time. Salam attempted to join the Indian Railways but was rejected due to failing medical optical and mechanical tests, and being too young. He continued his graduate studies at Government College University, receiving his MA in Mathematics in 1946. That same year, he was awarded a scholarship to St John's College, Cambridge, where he completed a BA degree with Double First-Class Honours in Mathematics and Physics in 1949.

In 1950, Salam received the Smith's Prize from Cambridge University for his outstanding pre-doctoral contribution to Physics. Although Fred Hoyle suggested he spend another year doing experimental physics at the Cavendish Laboratory, Salam preferred theoretical work. He returned to Jhang briefly before resuming his doctorate in the United Kingdom. He obtained his PhD in theoretical physics from the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge in 1951. His doctoral thesis, "Developments in quantum theory of fields," contained comprehensive and fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics, earning him international recognition and the Adams Prize upon its publication. During his doctoral studies, he famously solved an intractable problem regarding the renormalization of meson theory within six months, a problem that had challenged physicists like Paul Dirac and Richard Feynman. This solution attracted the attention of prominent scientists such as Hans Bethe, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and Dirac.

1.2. Academic Career

After completing his doctorate in 1951, Abdus Salam returned to Lahore, Pakistan, initially as a Professor of Mathematics at Government College University until 1954. In 1952, he was appointed Professor and Chair of the Department of Mathematics at the University of the Punjab. In this role, he attempted to modernize the university curriculum by introducing a course in Quantum mechanics for undergraduates. However, this initiative was reversed by the Vice-Chancellor, leading Salam to teach an evening course on Quantum Mechanics outside the official curriculum. Despite facing some opposition, he began to mentor students, with Riazuddin being his only student to study under him at the undergraduate, postgraduate, and postdoctoral levels. In 1953, his efforts to establish a research institute in Lahore were met with strong resistance from his peers.

In 1954, following the 1953 Lahore riots, Salam returned to Cambridge, rejoining St John's College as a professor of mathematics. In 1957, he was invited to take a chair at Imperial College London, where he, along with Paul Matthews, established the Theoretical Physics Group. This department grew to become a prestigious research center, attracting renowned physicists such as Steven Weinberg, Tom Kibble, Gerald Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, Riazuddin, and John Ward.

In 1957, the University of the Punjab awarded Salam an Honorary doctorate for his contributions to Particle physics. The same year, with the help of his mentor, he initiated a scholarship program for his students in Pakistan, maintaining strong ties with his home country through regular visits. At Cambridge and Imperial College, he cultivated a group of theoretical physicists, many of whom were his Pakistani students. At 33, in 1959, Salam became one of the youngest individuals to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). He also took a fellowship at Princeton University in 1959, where he met J. Robert Oppenheimer and discussed his research on neutrinos and the foundations of electrodynamics. In 1980, Salam was made a foreign fellow of the Bangladesh Academy of Sciences.

2. Scientific Career

Abdus Salam's scientific career was marked by groundbreaking contributions to theoretical and high-energy physics, culminating in his shared Nobel Prize for the electroweak unification theory.

2.1. Key Scientific Contributions

Salam's most significant achievement was his contribution to the electroweak unification theory, for which he shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg. This theory unified the weak nuclear force and the electromagnetic force into a single fundamental force, a cornerstone of the Standard Model of particle physics. He provided a mathematical postulation for the interaction between the Higgs boson and the electroweak symmetry theory, and predicted the existence of weak neutral currents and the W and Z bosons before their experimental discovery.

Beyond electroweak unification, Salam made other notable contributions, including:

- The Pati-Salam model, a Grand Unified Theory he proposed with Jogesh Pati in 1974, which aimed to unify the electroweak and strong nuclear forces. This model suggested a deep connection between Quarks and Leptons, postulating that lepton number could be considered a fourth quark colour, dubbed "violet."

- Work on the magnetic photon in 1966, where he showed a possible electromagnetic interaction between the Magnetic monopole and C-violation.

- Contributions to supersymmetry theory, particularly the formulation of Superspace and the formalism of superfields in 1974, as well as the theory of supermanifolds and supergeometry as a geometrical framework for understanding supersymmetry.

- The prediction of proton decay within the framework of grand unified theories.

2.2. Theoretical Physics Research

Salam had a prolific research career in theoretical and high-energy physics. Early in his career, he made important contributions to quantum electrodynamics and quantum field theory, extending them into particle and nuclear physics. He was particularly interested in mathematical series and their relation to physics. While he acknowledged the importance of nuclear physics (fission and power), he considered it a "non-pioneering" field as its fundamental principles were already established, dedicating himself instead to theoretical physics and encouraging Pakistan to focus on this area.

He worked extensively on the theory of the neutrino - an elusive particle first postulated by Wolfgang Pauli. Salam introduced chiral symmetry in neutrino theory, a crucial development for the subsequent theory of electroweak interactions. He later passed this work to his student, Riazuddin, who made pioneering contributions in the field. Salam also introduced the massive Higgs bosons into the theory of the Standard Model.

In 1963, Salam published theoretical work on the vector meson, introducing the interaction of vector mesons, photons (vector electrodynamics), and the renormalization of their mass after interaction. From 1961, he collaborated with John Clive Ward on symmetries and electroweak unification. In 1964, they developed a Gauge theory for the weak and electromagnetic interaction, leading to the SU(2) × U(1) model. Salam was convinced that all elementary particle interactions were ultimately gauge interactions. In 1968, he, along with Steven Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow, formalized the mathematical concept of their unified theory.

At Imperial College, Salam, in collaboration with Glashow and Jeffrey Goldstone, mathematically proved Goldstone's theorem, which states that a massless spin-zero object must appear in a theory as a result of the spontaneous breaking of a continuous global symmetry. In 1967-1968, Salam and Weinberg integrated the Higgs mechanism into Glashow's discovery, giving it a modern form within electroweak theory and thus theorizing half of the Standard Model.

2.3. Work at Imperial College London

Abdus Salam's tenure as a professor at Imperial College London, beginning in 1957, was a period of significant scientific output and the establishment of a world-renowned theoretical physics group. Along with Paul Matthews, he founded the Theoretical Physics Group at Imperial College, which attracted a host of brilliant physicists and became a hub for advanced research.

During his time at Imperial College, Salam collaborated extensively with colleagues and students. His work with John Clive Ward led to the development of a gauge theory for weak and electromagnetic interactions, culminating in the SU(2) × U(1) model. He also worked with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg to formulate the mathematical framework for the electroweak unification theory, which earned them the Nobel Prize. His collaboration with Glashow and Jeffrey Goldstone resulted in the mathematical proof of Goldstone's theorem. Salam also incorporated the Higgs mechanism into the electroweak theory, a crucial step in theorizing the Standard Model.

Salam's research at Imperial College also included pioneering work on the magnetic photon in 1966 and his continued efforts to unify forces, including the strong interaction, into a grand unified theory throughout the 1970s. As a teacher and mentor, he profoundly influenced his students, many of whom were Pakistani, fostering a vibrant research environment.

3. Contributions to Pakistan's Science Development

Abdus Salam played a pivotal and transformative role in shaping Pakistan's science policy and infrastructure, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's scientific landscape.

3.1. Role as Science Advisor and Policy Influence

In 1960, Abdus Salam returned to Pakistan to assume a government position under President Ayub Khan, replacing Salimuzzaman Siddiqui as the Science Advisor to the Ministry of Science and Technology. He also became the first Technical Member of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). At the time of Pakistan's independence in 1947, the country lacked a coherent science policy, with total expenditure on research and development being minimal, around 1.0% of Pakistan's GDP. The PAEC itself operated from a small room with fewer than ten scientists engaged in fundamental physics.

Salam embarked on a mission to expand Pakistan's physics research and development capabilities. He facilitated the training of over 500 Pakistani scientists abroad, primarily in the United States, to bolster the nation's scientific expertise. He actively encouraged Pakistani scientists working overseas, such as nuclear physicist Ishfaq Ahmad who was at CERN, to return to Pakistan and contribute to national scientific endeavors. Under Salam's guidance, PAEC established its Lahore Center-6, with Ishfaq Ahmad as its first director. By 1967, Salam had become a central figure in leading theoretical and particle physics research in Pakistan. He directed the establishment of the Institute of Physics at Quaid-e-Azam University, where research in theoretical and particle physics flourished, leading to worldwide recognition for Pakistani physicists.

3.2. Establishment of Scientific Research Institutes

From the 1950s, Salam had a long-held ambition to establish high-powered research institutes in Pakistan. Upon his return in 1960, he initiated significant institutional reforms. He oversaw the relocation of the PAEC Headquarters to a larger facility and the establishment of research laboratories across the country. Under his direction, Ishrat Hussain Usmani set up committees for plutonium and uranium exploration throughout Pakistan.

On 16 September 1961, Salam approached President Khan to establish Pakistan's first national space agency. This led to the creation of the Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO), with Salam serving as its founding director. Immediately after its establishment, Salam traveled to the United States and signed a space cooperation agreement with the US government. In November 1961, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) began constructing the Flight Test Center (FTC) at Sonmiani, a coastal town in Balochistan Province, where Salam served as its first technical director. He also visited the Pakistan Air Force Academy and met with Air Commodore Wladyslaw Turowicz, a Polish military scientist and aerospace engineer, who became the first technical director of the space center, initiating a rocket testing program. Another agreement with NASA provided training for Pakistani scientists and engineers, many of whom, like nuclear engineers Salim Mehmud and Tariq Mustafa, were inducted into SUPARCO upon their return.

Salam also played a crucial role in the development of Pakistan's nuclear energy program for peaceful purposes. In 1964, he became the head of Pakistan's IAEA delegation, representing the country for a decade. He advocated for the importance of nuclear power plants in Pakistan. His efforts led to the signing of a nuclear energy cooperation deal between Canada and Pakistan in 1965. Against the wishes of some government functionaries, Salam secured permission from President Ayub Khan to establish the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant. In 1965, the United States and Pakistan signed an agreement, facilitated by Salam, for the provision of a small research reactor (PARR-I). That same year, Salam and architect Edward Durell Stone signed a contract for the establishment of the Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology (PINSTECH) at Nilore, Islamabad, realizing his long-held dream of a dedicated research institute.

Salam also initiated the International Nathiagali Summer College on Physics and Contemporary Needs (INSC) in 1974, an annual gathering where scientists from around the world interact with local scientists in Pakistan. The first INSC conference focused on advanced particle and nuclear physics.

3.3. Involvement in Nuclear Programs

Abdus Salam's involvement in Pakistan's nuclear program is complex. While he recognized the importance of nuclear technology for peaceful purposes, his role in the country's atomic bomb project has been described as ambiguous. As early as the 1960s, Salam unsuccessfully proposed the establishment of a nuclear fuel reprocessing plant, which was deferred by Ayub Khan on economic grounds.

However, in the early 1970s, Salam became a strong advocate for the atomic bomb project. After India's first nuclear test in 1974, Pakistan's then-Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto orchestrated the development of a deterrence program. On 20 January 1972, Salam, as Science Advisor to the President of Pakistan, participated in a secret meeting of nuclear scientists with Bhutto in Multan, known as the 'Multan Meeting'. At this meeting, Bhutto entrusted Salam and appointed Munir Ahmad Khan as Chairman of PAEC and head of the atomic bomb program, with Salam's support.

A few months later, Salam, Khan, and Riazuddin briefed Bhutto on the nuclear weapons program. Following this, Salam established the 'Theoretical Physics Group' (TPG) within PAEC. This group, reporting directly to Salam, was tasked with conducting research in fast neutron calculations, hydrodynamics (related to explosion behavior), neutron diffusion problems, and the development of theoretical designs for Pakistan's nuclear weapon devices. The work on the theoretical design of the nuclear weapon was completed by the TPG under Riazuddin in 1977. In 1972, Salam also formed the Mathematical Physics Group, under Raziuddin Siddiqui, to research the theory of simultaneity during detonation and the mathematics of nuclear fission.

In March 1974, Salam and Khan established the Wah Group Scientist, responsible for manufacturing materials, explosive lenses, and triggering mechanisms for the weapon. Salam, Riazuddin, and Munir Ahmad Khan also held talks with military engineers at the Pakistan Ordnance Factories (POF), leading to the construction of the Metallurgical Laboratory in Wah Cantonment in 1976.

Salam remained associated with the nuclear weapons program until mid-1974. His relationship with Prime Minister Bhutto deteriorated and turned hostile after the Second Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan declared the Ahmadiyya Community non-Muslims. Salam publicly and strongly protested this decision and criticized Bhutto's control over science, leading to his departure from Pakistan. Despite this, he maintained close ties with the theoretical physics division at PAEC, which kept him informed about the scientific progress of the program. In the 1980s, Salam continued to approve appointments and supported Pakistani scientists through associateship programs at ICTP and CERN, engaging in theoretical physics research with his students. In 1978, Salam reportedly paid a secret visit to China with PAEC officials, playing a role in initiating industrial nuclear cooperation between the two countries. Even after leaving Pakistan, he continued to advise PAEC and the Theoretical and Mathematical Physics Group on important scientific matters.

3.4. Promoting Science within Pakistan

Abdus Salam was deeply committed to fostering scientific talent and research within Pakistan. He recognized the critical need for a robust scientific community to drive national development. His efforts included:

- Training and Scholarships:** He actively facilitated programs to send Pakistani scientists and engineers abroad for advanced training and PhDs in leading institutions in the UK and USA. Over 500 Pakistani physicists, mathematicians, and scientists benefited from these initiatives.

- Establishment of Research Groups:** He was instrumental in creating specialized research groups like the Theoretical Physics Group (TPG) within the PAEC, providing a platform for advanced theoretical work.

- Annual Scientific Gatherings:** The founding of the International Nathiagali Summer College on Physics and Contemporary Needs (INSC) in 1974 was a significant step. This annual college brings together scientists from around the world to Pakistan, fostering interaction, knowledge exchange, and promoting advanced physics and science within the country.

- Mentorship:** Salam served as a mentor and teacher to many prominent Pakistani scientists, including Ghulam Murtaza, Riazuddin, Kamaluddin Ahmed, Faheem Hussain, Raziuddin Siddiqui, Munir Ahmad Khan, Ishfaq Ahmad, and I. H. Usmani, inspiring them to pursue high-level research and contribute to Pakistan's scientific growth.

4. International Advocacy for Science

Abdus Salam's vision extended beyond Pakistan, encompassing a global commitment to advancing science, particularly in the developing world.

4.1. Founding and Directing the ICTP

In 1964, Abdus Salam founded the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy. He served as its director until 1993. The ICTP was established under the auspices of UNESCO and the IAEA with the aim of fostering scientific collaboration and supporting scientists from developing countries. It provided a crucial platform for researchers from the Global South to engage in high-level theoretical physics research, interact with leading scientists, and overcome the isolation often faced in their home countries. In 1997, in honor of his foundational contributions, the institute was renamed the "Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics".

4.2. Advocacy for Science in Developing Countries

Salam was a passionate champion for scientific progress in the developing world. He firmly believed that "scientific thought is the common heritage of mankind" and that developing nations must invest in their own scientists to bridge the gap between the Global South and the Global North, thereby contributing to a more peaceful world.

His efforts to promote science globally included:

- Founding the Third World Academy of Sciences (TWAS):** In 1983, Salam founded TWAS, an organization dedicated to supporting scientific excellence and capacity building in developing countries.

- United Nations Committees:** He served on numerous United Nations committees focused on science and technology in developing nations, advocating for policies and initiatives that would bolster scientific capabilities.

- International Centers:** He was a leading figure in the creation of several international centers aimed at advancing science and technology, reflecting his belief in collaborative global efforts.

- World Cultural Council:** In 1981, Salam became a founding member of the World Cultural Council, further demonstrating his commitment to the broader impact of knowledge and culture.

Even after his departure from Pakistan, Salam maintained strong ties with his home country's scientific community. He consistently invited Pakistani scientists to the ICTP and sustained a research program specifically for them, ensuring continued opportunities for their professional development and engagement with global physics.

5. Personal Life

Abdus Salam was a private individual who maintained a clear distinction between his public and personal lives.

5.1. Family and Marriage

Abdus Salam married twice, both times in accordance with Islamic law. His first wife was a cousin. His second marriage was to Professor Dame Louise Johnson, a distinguished Professor of molecular biophysics at Oxford University. At the time of his death, he was survived by three daughters and a son from his first marriage, and a son and a daughter from his second marriage. Among his daughters are Anisa Bushra Salam Bajwa and Aziza Rahman.

5.2. Religious Beliefs and Identity

Salam was a devout member of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, and his faith was a fundamental aspect of his life and scientific work. He often expressed that he viewed his scientific endeavors as a reflection on "the verities of Allah's created laws of nature," considering it a "bounty and a grace" to glimpse part of God's design.

In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Physics, Salam famously quoted verses from the Quran (67:3-4):

"Thou seest not, in the creation of the All-merciful any imperfection, Return thy gaze, seest thou any fissure? Then Return thy gaze, again and again. Thy gaze, Comes back to thee dazzled, aweary."

He interpreted this as the "faith of all physicists," suggesting that the deeper one seeks, the greater the wonder and dazzlement.

In 1974, the Parliament of Pakistan unanimously passed the Second Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan, which declared Ahmadis to be non-Muslims. In protest against this decree, Salam left Pakistan for London. Despite his departure, he did not completely sever his ties with Pakistan's scientific community, maintaining close associations with the Theoretical Physics Group and academic scientists from the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission.

6. Political Stance and Social Impact

Abdus Salam's life was significantly shaped by the political climate in Pakistan, particularly the state-sponsored discrimination against his religious community, which profoundly influenced his views on minority rights and religious freedom.

6.1. Ahmadiyya Community Persecution and Stance

In 1974, the Parliament of Pakistan passed a constitutional amendment that officially declared the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, to which Abdus Salam belonged, as non-Muslims. This legislative act led to severe persecution and discrimination against Ahmadis in Pakistan. In a powerful public protest against this declaration, Salam left Pakistan for London. His departure marked a significant turning point in his relationship with his home country, which he loved deeply despite the injustice he faced.

Even after leaving, he maintained informal connections with Pakistani scientists, but his public stance against the persecution of his community created an open hostility between him and the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. This discriminatory policy meant that despite his global scientific acclaim, Salam's legacy was often ignored or downplayed within Pakistan's official narratives and educational system.

6.2. Views on Minority Rights and Religious Freedom

Abdus Salam's personal experience as a member of a persecuted minority deeply informed his perspective on minority rights and religious freedom. He became a vocal advocate for these principles, emphasizing the importance of tolerance and respect for diverse beliefs. His life served as a poignant example of how state-sponsored discrimination can alienate even its most brilliant citizens and hinder national progress. He believed that scientific thought was a common heritage of humanity and that a nation's progress depended on embracing all its talents, regardless of religious affiliation.

7. Death and Funeral

Abdus Salam's passing marked the end of a remarkable life, but his burial in Pakistan was marred by the very religious discrimination he had protested.

7.1. Circumstances of Death

Abdus Salam died on 21 November 1996, at the age of 70, in Oxford, England. The cause of his death was progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare neurological disorder.

7.2. Funeral and Cemetery Controversy

Following his death, Abdus Salam's body was returned to Pakistan. It was kept in Darul Ziafat, where approximately 13,000 men and women visited to pay their last respects. His funeral prayers were attended by an estimated 30,000 people.

Salam was buried in Bahishti Maqbara, a cemetery established by the Ahmadiyya Community in Rabwah, Punjab, Pakistan, alongside his parents' graves. However, his burial became a focal point of the state-sponsored discrimination against the Ahmadiyya community. The epitaph on his tomb initially read "First Muslim Nobel Laureate". In a controversial act, the Pakistani government, acting on the orders of a local magistrate and in accordance with Ordinance XX of 1984 (which defines Ahmadis as non-Muslims), removed the word "Muslim" from his headstone, leaving only his name. This act underscored the official declaration by Pakistan that Ahmadis are non-Muslims, making it the only nation to officially do so.

8. Legacy and Evaluation

Abdus Salam's legacy is immense, spanning his profound impact on theoretical physics, his foundational role in Pakistan's scientific development, and his tireless international advocacy for science. However, his recognition in his home country remains complicated by religious prejudice.

8.1. Nobel Prize and Major Awards

In 1979, Abdus Salam was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, sharing it with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg. The Nobel Foundation cited their contributions "for their contributions to the theory of the unified weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, including, inter alia, the prediction of the weak neutral current."

Throughout his lifetime, Salam received numerous high civil and science awards from around the world, recognizing his exceptional contributions. These include:

- Nobel Prize in Physics (Stockholm, Sweden) (1979)

- Hopkins Prize (Cambridge University) for "the most outstanding contribution to Physics during 1957-1958"

- Adams Prize (Cambridge University) (1958)

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1959)

- Smith's Prize (Cambridge University) (1950)

- Sitara-e-Pakistan by the President of Pakistan (1959)

- Pride of Performance Award by the President of Pakistan (1958)

- First recipient of James Clerk Maxwell Medal and Prize (Physical Society, London) (1961)

- Hughes Medal (Royal Society, London) (1964)

- Atoms for Peace Award (Atoms for Peace Foundation) (1968)

- J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize and Medal (University of Miami) (1971)

- Guthrie Medal and Prize (1976)

- Sir Devaprasad Sarvadhikary Gold Medal (Calcutta University) (1977)

- Matteuci Medal (Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rome) (1978)

- John Torrence Tate Medal (American Institute of Physics) (1978)

- Royal Medal (Royal Society, London) (1978)

- Nishan-e-Imtiaz by the President of Pakistan (1979)

- Einstein Medal (UNESCO, Paris) (1979)

- Shri R.D. Birla Award (India Physics Association) (1979)

- Order of Andrés Bello (Venezuela) (1980)

- Order of Istiqlal (Jordan) (1980)

- Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (1980)

- Josef Stefan Medal (Josef Stefan Institute, Ljublijana) (1980)

- Gold Medal for Outstanding Contributions to Physics (Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, Prague) (1981)

- Peace Medal (Charles University, Prague) (1981)

- Doctor of Science from University of Chittagong (1981)

- Lomonosov Gold Medal (USSR Academy of Sciences) (1983)

- Premio Umberto Biancamano (Italy) (1986)

- Dayemi International Peace Award (Bangladesh) (1986)

- First Edinburgh Medal and Prize (Scotland) (1988)

- "Genoa" International Development of Peoples Prize (Italy) (1988)

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1989)

- Catalunya International Prize (Spain) (1990)

- Copley Medal (Royal Society, London) (1990)

8.2. Institutions and Places Named After Him

Abdus Salam's profound impact is recognized through numerous institutions and places named in his honor worldwide:

- The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy, was renamed in his honor in 1997.

- The Abdus Salam Centre for Physics (Department of Physics) at Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad, Pakistan.

- The Abdus Salam National Centre for Mathematics (ASNCM) at Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan.

- The Abdus Salam Chair in Physics (ASCP) at Government College University, Lahore, established in 1999.

- The Abdus Salam School of Mathematical Sciences in Lahore, Pakistan, established in 2003.

- The Edward Bouchet Abdus Salam Institute (EBASI), renamed in 1998.

- The Abdus Salam Library at Imperial College London, renamed in June 2023.

- A street named 'Abdus Salam Street' in Vaughan, Ontario, Canada, near the headquarters of the Canadian branch of the Ahmadiyya Community.

- 'Route Salam' at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland.

- In November 2020, English Heritage erected a blue plaque in Salam's honor at his London home in Campion Road, Putney, where he lived for almost 40 years.

- In December 2016, Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif approved the renaming of Quaid-i-Azam University's (QAU) physics center to the Professor Abdus Salam Center for Physics. Additionally, the Professor Abdus Salam Fellowship was established to provide five annual fully funded PhD scholarships in Physics at leading international universities for Pakistani students.

8.3. Impact on Physics and Pakistani Science

Abdus Salam's scientific impact on the field of physics is immense, particularly his role in the electroweak unification theory, which forms a cornerstone of the Standard Model. His work on neutrino theory, Higgs bosons, supersymmetry, and grand unified theorys significantly advanced particle physics. His contributions to the 2012 success in the search for the Higgs boson were also recognized.

In Pakistan, Salam is widely regarded as the "father of Pakistan's school of Theoretical Physics" and a pivotal figure in the development of the nation's science. He was a charismatic and iconic figure who inspired a generation of Pakistani scientists. His students, colleagues, and engineers remember him as a brilliant teacher and an engaging researcher who motivated others to pursue scientific excellence. The International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), which he founded, continues to train scientists from developing countries, extending his legacy of global scientific capacity building. He also founded the Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO) and served as its first director, laying the groundwork for Pakistan's space program.

8.4. Historical Assessment and Social Recognition

Despite his monumental achievements and global recognition, Abdus Salam's legacy in Pakistan is often overlooked or actively suppressed within the official education system. This deliberate neglect is primarily attributed to his affiliation with the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, which has faced state-sponsored discrimination in Pakistan since the 1970s.

Many young Pakistanis are unaware of his contributions, and his name is rarely mentioned in Pakistani school textbooks. This historical revisionism is a direct consequence of the legal and social persecution of Ahmadis. For instance, in 2020, a group of students in Gujranwala desecrated an image of Salam at a college while chanting anti-Ahmadiyya slogans, highlighting the deep-seated prejudice that persists.

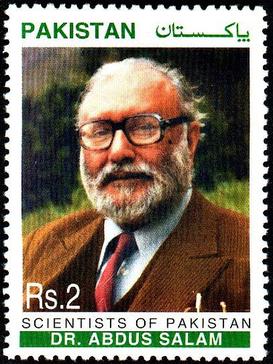

However, there have been efforts to recognize him. In 1998, the Government of Pakistan issued a commemorative stamp honoring Salam as part of its "Scientists of Pakistan" series. His alma mater, Government College Lahore (now a university), established the Abdus Salam Chair in Physics and the Abdus Salam School of Mathematical Sciences in his name. In 2009, the original Nobel Prize Certificate was gifted to his alma mater. In 2011, a conference was held at GCU's Salam Chair in Physics, where his students discussed his life and works, with The News International referring to him as the "great Pakistan scientist."

Prominent Pakistani scientists, many of whom were his students, have consistently championed his legacy. Ghulam Murtaza, a professor of plasma physics and Salam's student, recalled how Salam's lectures captivated audiences and how he treated everyone with respect, able to "sift jewels from the sand." Ishfaq Ahmad, a lifelong friend, noted Salam's role in sending hundreds of Pakistani scientists for PhDs abroad. Munir Ahmad Khan, who headed Pakistan's nuclear programs, expressed regret that Pakistan had treated Salam unfairly and hoped the nation would eventually overcome its prejudice to fully embrace his contributions. As one newspaper noted, "it has taken nearly four decades for this country to honour a globally renowned scientist who was one of its own... For Dr Salam was an Ahmadi, a persecuted minority in Pakistan, and his faith rather than his towering achievements was the yardstick by which he was judged."

9. Documentaries and Media

Abdus Salam's life and work have been the subject of several documentaries, shedding light on his scientific achievements and the challenges he faced.

- Salam - the film: Kailoola Productions began researching and developing a film on Abdus Salam's science and life in 2004. A fundraising teaser was released in 2017. The documentary film, Salam: The First ****** Nobel Laureate, directed by Indian-American documentary filmmaker Anand Kamalakar, was released on Netflix in October 2019.

- Abdus Salam: The Dream of Symmetry: Pilgrim Films released this documentary in September 2011. It aims to present "the extraordinary figure of Abdus Salam, who not only was an outstanding scientist but also a generous humanitarian and a valuable person. His rich and busy life was an endless quest for symmetry, that he pursued in the universe of physical laws and in the world of human beings."

10. Awards Named After Salam

Abdus Salam's commitment to fostering scientific talent and supporting developing countries led to the establishment of several awards in his name, often funded by his own Nobel Prize money.

- The Abdus Salam Award (Salam Prize): This award was established in 1980 by his students Riazuddin, Fayyazuddin, and Asghar Qadir, to recognize high achievements and contributions in physical and natural sciences by scientists residing in Pakistan. Salam himself donated his Nobel Prize money for this purpose, believing he had no personal use for it. The award was first given in 1981 and is administered by the Center for Advanced Mathematics and Physics (CAMP).

- The Abdus Salam Medal: Presented by the Third World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) in Trieste, Italy, this medal was first awarded in 1995. It recognizes individuals who have significantly served the cause of science in the Developing World.

- The Abdus Salam Shield of Honor in Mathematics: Initiated by the National Mathematical Society of Pakistan in 2015, this award promotes and recognizes quality research in Mathematics within Pakistan. It was first awarded in 2016.

- Abdus Salam Science Fairs: Two annual Abdus Salam science fairs are organized as national events for young scientists from the Ahmadiyya Community in Canada and the United States, aiming to motivate youth toward scientific endeavors.