1. Overview

Æthelred I (also spelled Aethelred or Ethelred; Æthel-rædnoble counselEnglish, Old), who reigned from 865 until his death in 871, was the King of Wessex. He was the fourth of five sons of King Æthelwulf, with four of his brothers eventually ascending to the throne. Æthelred succeeded his elder brother, Æthelberht, and was in turn succeeded by his youngest brother, Alfred the Great. His reign was dominated by the escalating threat of Viking invasions, particularly from the formidable Great Heathen Army, which launched a full-scale assault on Wessex. Despite military setbacks, Æthelred demonstrated significant leadership in defending his kingdom and made a lasting impact on early English coinage by unifying the currency design across southern England. This period of intense conflict and strategic development laid crucial groundwork for the future unification of England.

2. Background and Family

Æthelred I's lineage was deeply rooted in the West Saxon royal house, which had recently established a more stable dynastic succession. His family played a crucial role in the political landscape of ninth-century England, particularly in the face of increasing Viking incursions.

2.1. Ancestry and Parents

Æthelred's grandfather, Ecgberht, became King of Wessex in 802. At the time, it was uncertain whether he would establish a lasting dynasty, as for two centuries, three families had vied for the West Saxon throne, and no son had directly succeeded his father. Ecgberht's claim was based on his paternal descent from Cerdic, the legendary founder of the West Saxon dynasty, making him an ætheling, a prince eligible for the throne. However, after Ecgberht's reign, mere descent from Cerdic was no longer sufficient; subsequent West Saxon kings were all his direct descendants and sons of previous kings, signifying a new era of dynastic stability.

Ecgberht's victory over Mercia at the Battle of Ellendun in 825 ended Mercian supremacy in southern England, leading to an alliance between Wessex and Mercia that became vital for resisting Viking attacks. In 853, Æthelred's father, King Æthelwulf, led a West Saxon force to aid King Burgred of Mercia in suppressing a Welsh rebellion. This alliance was further cemented by the marriage of Burgred to Æthelwulf's daughter, Æthelswith. Ecgberht had also expanded West Saxon control by invading the Mercian sub-kingdom of Kent in 825, appointing Æthelwulf as King of Kent. While both Ecgberht and Æthelwulf appointed their sons as underkings in Kent, maintaining overall control and preventing them from issuing their own coinage, this demonstrated a strategic effort to consolidate power.

Æthelred's father, Æthelwulf, died in 858. His mother was Osburh, a woman of West Saxon royal descent.

2.2. Siblings

Æthelred was the fourth of five sons of King Æthelwulf and Osburh. Four of his brothers eventually became kings of Wessex. His elder brother, Æthelberht, succeeded Æthelwulf and, for the first time, united the kingdoms of Wessex and Kent into a single entity. Æthelred's youngest brother was Alfred the Great, who would succeed him.

A significant point of contention between Æthelred and Alfred concerned their father Æthelwulf's will. Æthelwulf had bequeathed property jointly to three of his sons: Æthelbald, Æthelred, and Alfred, with the stipulation that the longest-living brother would inherit all of it. After Æthelbald's death in 860, Æthelred and Alfred, still young, agreed to entrust their share to King Æthelberht, who promised to return it intact. Upon Æthelred's accession, Alfred requested his share at a meeting of the witan (assembly of leading men). However, Æthelred stated that he had found it too difficult to divide the property and would instead leave the entirety to Alfred upon his death. This dispute, along with Alfred's infrequent witnessing of Æthelred's charters, suggests a strained relationship between the brothers. Some historians interpret Æthelwulf's bequest as encompassing all his personal bookland, implying an intention for the throne to pass sequentially among his sons to keep the bookland with the crown. However, other scholars argue the bequest was merely provision for his younger sons upon reaching adulthood.

2.3. Marriage and Children

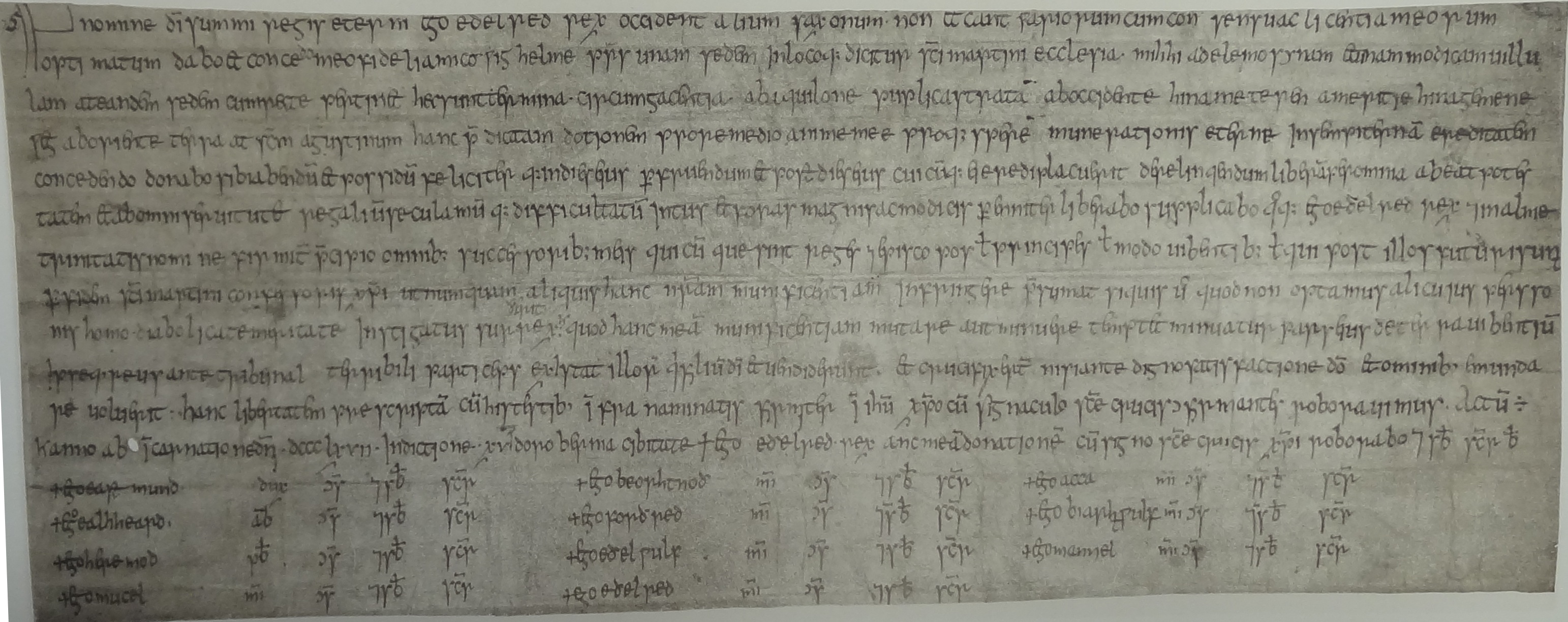

Æthelred married a woman named Wulfthryth at an unknown date after his accession. In the ninth century, the wives of West Saxon kings typically held a low status and were rarely granted the title of regina (queen). This omission was later justified by Alfred the Great due to the alleged misconduct of an earlier queen. However, Wulfthryth is recorded as Wulfthryth regina in a charter (S 340) from 868, suggesting she held a higher status than most royal consorts of the period. The only other ninth-century king's wife known to have received this title was Judith of Flanders, Æthelwulf's second wife and a great-granddaughter of Charlemagne.

Wulfthryth and Æthelred had two known sons: Æthelhelm and Æthelwold. Æthelred may have had a third son, Oswald, who witnessed charters as filius regis (king's son), but this is generally dismissed by historians as only Æthelhelm and Æthelwold are mentioned in Alfred's will regarding disputes over their treatment after Alfred's succession. Wulfthryth may have been of Mercian origin or the daughter of Wulfhere, Ealdorman of Wiltshire. Some historians suggest that Æthelred's decision to highlight his wife's status as queen in a charter might have been an attempt to strengthen his own sons' claims to the succession. Upon Æthelred's death, his sons were still infants, leading to their exclusion from the throne in favor of his younger brother, Alfred.

3. Early Life

Æthelred's early life was marked by his royal upbringing and early exposure to the political and religious currents of his time, preparing him for the challenges he would later face as king.

3.1. Childhood and Education

Æthelred was born around 845 or 848. He was likely a year or so older than his younger brother, Alfred, who was born between 848 and 849. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 853, Alfred was sent by his father to Rome and was consecrated by the Pope as king. While historians generally agree that Alfred was too young to be consecrated king, a letter from Pope Leo IV to Æthelwulf explains that Alfred was decorated "as a spiritual son, with the dignity of the belt and the vestments of the consulate, as is customary with Roman consuls." The contemporary Liber Vitae of San Salvatore, Brescia, records the names of both Æthelred and Alfred, indicating that Æthelred also journeyed to Rome. It is probable that Æthelred also received a similar papal decoration, though later chroniclers, focused on Alfred's future greatness, did not emphasize Æthelred's presence. This journey highlights the strong religious influence on their royal education and the close ties between the West Saxon royal family and the Papacy.

3.2. Pre-accession Activities

Æthelred began witnessing his father's charters as filius regis (king's son) in 854, a title he held until his accession in 865. There is evidence suggesting he may have served as an underking before becoming king. In 862 and 863, he issued his own charters under the title "King of the West Saxons." This likely occurred while acting as a deputy or in the absence of his elder brother, King Æthelberht, as there is no record of conflict between them. Furthermore, Æthelred continued to witness Æthelberht's charters as a king's son in 864, indicating a cooperative arrangement rather than a challenge to his brother's authority. These early activities demonstrate his involvement in governance and the development of administrative structures within the kingdom prior to his full reign.

4. Reign

Æthelred I's reign as King of Wessex was predominantly defined by the relentless and escalating threat of Viking invasions, which forced him to dedicate significant resources and strategic efforts to defense. Despite these military challenges, he also implemented important policies, particularly in the realm of coinage, that contributed to the kingdom's stability and future development.

4.1. Accession

Æthelred ascended to the throne of Wessex upon the death of his elder brother, Æthelberht, in 865. At the time of his accession, Wessex and Mercia maintained a close alliance, which had been crucial in resisting earlier Viking incursions. However, the nature of Viking attacks on England underwent a dramatic shift in 865. Previously, the country had experienced sporadic raids, but now it faced a sustained invasion by a large force, known to contemporaries as the Great Heathen Army, with the explicit aim of conquest and settlement. This new, formidable threat immediately became the defining challenge of Æthelred's reign.

During his reign, Æthelred used various titles in his charters. He was often referred to by his father's usual title, Rex Occidentalium Saxonum (King of the West Saxons), and in some documents, "King of the West Saxons and the Men of Kent," or simply "King" or "King of the Saxons." The consistent style of charters issued during his and his elder brothers' reigns suggests a centralized administrative agency at work for many years.

4.2. The Viking Invasions

The arrival of the Great Heathen Army in England in 865 marked a turning point in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms' struggle against Viking expansion. This large force initially landed in East Anglia, where King Edmund bought peace by paying tribute, allowing the Vikings to consolidate their strength for a year. They then marched north, conquering Northumbria and installing a puppet king in York. In late 867, they advanced into Mercia, seizing Nottingham for the winter. Æthelred's brother-in-law, King Burgred, appealed to Wessex for aid. Æthelred and Alfred led a substantial West Saxon army to Nottingham and besieged the Vikings, but the invaders refused to engage outside the town's fortifications. Unable to breach the earthworks, the combined Mercian and West Saxon forces eventually resorted to buying off the Vikings, who then retreated to York.

In 869, the Vikings returned to East Anglia, conquering the kingdom and killing King Edmund. By December 870, led by Kings Bagsecg and Halfdan, they launched a full-scale invasion of Wessex, occupying Reading around 28 December. The Vikings immediately fortified the town with a ditch and rampart between the River Thames and River Kennet.

4.2.1. Battles of Reading and Ashdown

Three days after their arrival in Reading, the Vikings dispatched a large foraging party, which was decisively defeated by an army of local levies under Æthelwulf, Ealdorman of Berkshire, at the Battle of Englefield. Four days later, around 4 January 871, Æthelred and Alfred arrived with the main West Saxon army, joining Æthelwulf's forces for an assault on the Danes at the Battle of Reading. The West Saxons fought their way to the town, slaughtering Vikings outside the walls, but were ultimately repelled by a fierce Viking counter-attack from the town gate. Ealdorman Æthelwulf was among the casualties, his body secretly transported for burial in his native Derby. According to the twelfth-century chronicler Geoffrey Gaimar, Æthelred and Alfred narrowly escaped by utilizing their knowledge of the local terrain, fording the River Loddon at Twyford and proceeding to Whistley Green, approximately 6 mile east of Reading, to evade their pursuers.

Just four days later, around 8 January, the armies clashed again at the Battle of Ashdown. The exact location remains unknown, though Kingstanding Hill, about 13 mile north-west of Reading, is a possibility. The Vikings gained an initial advantage by deploying along a ridge top, dividing their forces under their two kings and their earls. The West Saxons mirrored this formation, with Æthelred facing the kings and Alfred the earls. According to Asser's account, King Æthelred retired to his tent to hear Mass, refusing to leave until the priest had finished, while Alfred led his forces into battle. Both sides formed shield walls. Alfred, risking being outflanked, decided to charge, leading his men into the fray. The battle raged fiercely around a small thorn tree, culminating in a West Saxon victory. Although Asser's biography emphasizes Alfred's decisive role and implies Æthelred's delay, military historians like John Peddie suggest Æthelred's delay was a militarily sound decision, waiting for the optimal moment to join. The Vikings suffered heavy losses, including King Bagsecg and five earls: Sidroc the Old, Sidroc the Younger, Osbern, Fræna, and Harold. The West Saxons pursued the fleeing Vikings until nightfall, inflicting further casualties.

4.2.2. Battles of Basing and Meretun

Despite the victory at Ashdown, the West Saxon triumph was short-lived. Two weeks later, Æthelred and Alfred faced another defeat at the royal estate of Basing in the Battle of Basing. A two-month lull followed before the West Saxons and Vikings met again at an unknown location called Meretun (possibly Marden near Devizes or Martin in Hampshire). In the battle on 22 March, the Vikings once again divided their forces. The West Saxons initially gained the upper hand, putting both Viking divisions to flight, but the Vikings regrouped and ultimately secured control of the battlefield. The West Saxons suffered significant losses, including Heahmund, the Bishop of Sherborne. These continuous engagements illustrate the persistent threat posed by the Vikings and the strenuous defensive efforts undertaken by Æthelred and his forces throughout his reign.

4.3. Coinage

Æthelred's reign marked a "critical point in the development of the English coinage," according to numismatists Adrian Lyons and William Mackay. In the late eighth and ninth centuries, the only coin denomination produced in southern England was the silver penny. As of 2007, 152 coins struck by 32 different moneyers during Æthelred's reign have been recorded.

His initial "Four Line" coinage issue was stylistically similar to the "Floriate Cross" penny of his predecessor, Æthelberht. However, Æthelred soon abandoned this design and adopted the "Lunettes" design used by his Mercian brother-in-law, Burgred. This crucial decision resulted in the first common coinage design across southern England, fostering a form of monetary union. Rory Naismith, a historian and numismatist, notes that this adoption of a Mercian-based coin-type, rather than a local tradition, occurred in 865, the same year the Great Heathen Army arrived, signifying "the beginning of the end for separate coinages in separate kingdoms."

Lyons and Mackay emphasize that these developments in the late 860s were an "essential precursor" to the unified reform coinage of King Edgar a century later, which established the most sophisticated monetary system in Europe for 150 years. This convergence of coinage also serves as tangible evidence of growing collaboration between Mercia and Wessex, foreshadowing the eventual creation of a unified England.

The unified coinage design reinforced the mingling of economic interests and the military alliance between the two kingdoms against the Vikings. Coin hoards from Wessex prior to this change contained few non-Wessex coins. After the adoption of the common Lunettes design, however, coins from both Wessex and Mercia were widely circulated in both kingdoms, with Æthelred I's coins forming a minor proportion of total finds in Wessex hoards. Between 1 M and 1.5 M Æthelred I "Regular Lunette" coins were produced, though this was significantly less than in Mercia. The adoption of the Mercian design likely reflected its established use for over twelve years, its simple, easily replicable design, and the greater strength of the Mercian economy.

The majority of surviving Æthelred I coins are of the "Regular Lunettes" design, with 118 coins struck by 21 moneyers, six of whom also worked for Burgred. These coins are noted for their consistent design and high quality of execution, primarily produced by moneyers in Canterbury, with a few from London. Only one coin is known to have been produced in Wessex itself. There were also "Irregular Lunettes" issues, including a degraded and crude variant, possibly indicative of a breakdown in quality control towards the end of Æthelred's reign due to the intense pressure from Viking attacks. Alfred the Great continued to use the Lunettes design for a short period after his accession in 871, but the design largely disappears from hoards deposited after approximately 875.

5. Death and Succession

Æthelred I's death marked a critical juncture for the Kingdom of Wessex, leading to the unexpected succession of his younger brother, Alfred, and setting the stage for future dynastic disputes.

5.1. Death

Æthelred I died shortly after Easter in 871, which fell on 15 April that year. According to Asser, Alfred the Great's biographer, Æthelred "went the way of all flesh, having vigorously and honourably ruled the kingdom in good repute, amid many difficulties, for five years." Other accounts suggest he died from wounds sustained in battle against the Vikings, possibly at Witshamton near Wimborne, suffering greatly. He was likely no older than thirty at the time of his death.

5.2. Burial

Æthelred was buried at the royal minster at Wimborne in Dorset. This minster had been founded by Saint Cuthburh, a sister of his ancestor, Ingild. The location of his burial later gained symbolic importance, as it was one of the two places where his son, Æthelwold, launched his rebellion against Alfred's successor, Edward the Elder.

5.3. Succession

Æthelred had two sons, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold. Had he lived until they reached adulthood, it is unlikely that Alfred would have become king. However, as both sons were still young children at the time of Æthelred's death, his younger brother, Alfred the Great, succeeded him to the throne. This decision, while necessary for the stability of the kingdom during a period of intense Viking threat, bypassed Æthelred's direct male heirs.

Æthelhelm died before Alfred. However, Æthelwold later disputed the throne with Edward the Elder, Alfred's son, after Alfred's death in 899. Æthelwold's rebellion, launched in 901, was ultimately unsuccessful, and he was killed in battle around 904 or 905. The exclusion of Æthelred's young sons from the immediate succession, and the subsequent rebellion by Æthelwold, highlight the complex principles of royal succession at the time, where the need for a strong, adult leader in times of crisis could override traditional hereditary claims.

6. Assessment and Legacy

Æthelred I's reign, though brief and overshadowed by relentless Viking invasions, was a period of crucial transition and foundational efforts that significantly impacted the future of Wessex and the eventual unification of England.

6.1. Positive Assessment

Despite facing overwhelming odds, Æthelred demonstrated commendable leadership in defending Wessex against the relentless incursions of the Great Heathen Army. His efforts, alongside his brother Alfred, in leading armies to confront the Vikings at battles like Reading, Ashdown, Basing, and Meretun, showcased a commitment to protecting his kingdom and its people. While not always victorious, these engagements were vital in slowing the Viking advance and preventing the complete collapse of West Saxon resistance, thereby preserving the core of Anglo-Saxon power.

Beyond military defense, Æthelred's contributions to monetary policy were particularly significant. By adopting the Mercian "Lunettes" design for coinage, he effectively created a unified currency across southern England for the first time. This act fostered greater economic integration between Wessex and Mercia, strengthening their alliance against the common Viking threat. Numismatists view this as a critical step that foreshadowed the later unification of England and the sophisticated coinage reforms of King Edgar. This move towards a standardized currency reflects a strategic vision for state-building and economic stability amidst extreme external pressures. His piety, as noted by contemporary accounts, also suggests a leader deeply committed to the spiritual well-being of his realm.

6.2. Criticism and Controversy

Æthelred's reign was undeniably marked by military setbacks, including defeats at Reading, Basing, and Meretun. These losses, coupled with the persistent Viking presence, indicate the immense challenges he faced and the limitations of his military successes. While his decision to delay joining the Battle of Ashdown has been debated, with some seeing it as an act of piety rather than strategic acumen, military historians suggest it was a sound tactical choice.

A notable controversy surrounded the inheritance dispute with his younger brother Alfred. The disagreement over their father Æthelwulf's will, which bequeathed property jointly to three sons, created tension between Æthelred and Alfred. Alfred's later account in his will, detailing the difficulty in dividing the property and Æthelred's promise to leave it all to Alfred upon his death, suggests a strained relationship between the brothers. This dispute, along with the subsequent bypassing of Æthelred's infant sons for Alfred's succession, highlights the dynastic complexities and potential for internal conflict even in the face of external threats. The later rebellion by Æthelred's son, Æthelwold, against Alfred's successor further underscores the unresolved issues of succession from Æthelred's reign.

6.3. Impact on Descendants

Although Æthelred's direct sons, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold, did not immediately succeed him, his descendants played a significant role in governing Anglo-Saxon England in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. His son Æthelwold's unsuccessful rebellion against Edward the Elder in 899, launched from places symbolically important as his father's burial site, demonstrated the lingering dynastic claims and potential for instability.

Later, Æthelred's lineage produced prominent figures such as Ealdorman Æthelweard, a historian who claimed descent as Æthelred's great-great-grandson. Æthelweard and his son Æthelmær were influential magnates, serving as ealdormen of the western provinces and governing west Wessex. This family's prominence, however, came to an end after Cnut conquered England in 1016, leading to the execution of one of Æthelmær's sons in 1017 and the banishment of a son-in-law in 1020. Another notable descendant was Æthelnoth, who served as Archbishop of Canterbury until 1038. The fact that King Eadwig was forced to annul his marriage to Ælfgifu due to consanguinity, possibly because she was Æthelweard's sister and thus Æthelred's descendant, further illustrates the enduring influence of Æthelred's lineage on the political and social fabric of Anglo-Saxon England.