1. Early Life and Accession

Ecgberht's ascent to the throne of Wessex was shaped by a complex lineage, the political dominance of Mercia, and a period of forced exile that honed his understanding of governance.

1.1. Family and Ancestry

Historians debate Ecgberht's precise ancestry. The earliest version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, known as the Parker Chronicle, provides a genealogical preface that traces Ecgberht's lineage, through his father Ealhmund of Kent, back to Ingild, the brother of King Ine of Wessex, who abdicated in 726. This lineage further extends to Cerdic, the legendary founder of the House of Wessex. While his descent from Ingild is generally accepted, the earlier connections to Cerdic are viewed with skepticism by some modern historians. Heather Edwards, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, suggests that Ecgberht was of Kentish origin and that his West Saxon descent might have been fabricated during his reign to enhance his legitimacy. Conversely, Rory Naismith posits that a Kentish origin is unlikely and that Ecgberht was more probably born into "good West Saxon royal stock."

The name of Ecgberht's wife remains unknown. A 15th-century chronicle identifies her as Redburga, reputedly a relative of Charlemagne whom he married during his exile in Francia. However, academic historians largely dismiss this claim due to its late date and lack of contemporary evidence. Their only known child was his son, Æthelwulf. Ecgberht is also believed to have had a half-sister named Alburga, who later became a saint known for founding Wilton Abbey. She was married to Wulfstan, an ealdorman of Wiltshire, and became an abbess upon his death in 802.

1.2. Political Context and Exile

During Ecgberht's youth, the political landscape of Anglo-Saxon England was largely dominated by Offa of Mercia, who reigned from 757 to 796. Although the relationship between Offa and Cynewulf of Wessex, king of Wessex from 757 to 786, is not extensively documented, Cynewulf appears to have maintained some independence, not acknowledging Offa as an overlord despite a defeat at the Battle of Bensington in 779. However, Offa's influence was significant in the southeast, particularly in Kent, where he may have supported the installation of Heahberht of Kent in 764. Another Ecgberht, Ecgberht II of Kent, ruled Kent in the 770s, followed by Ecgberht's father, Ealhmund, who appears as king in 784. Ealhmund's reign was brief, as Offa exerted strong control, possibly annexing Kent in the late 780s.

It is suggested that the young Ecgberht fled to Wessex around 785. In 786, after Cynewulf's murder, Ecgberht contested the succession but was defeated by Beorhtric of Wessex, possibly with Offa's aid. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that Ecgberht was then exiled to Francia by Beorhtric and Offa, where he spent three years before becoming king. While the text explicitly states "iii" for three years, some modern scholars argue it might be a scribal error and should read "xiii" for thirteen years, which would account for a longer period of exile, possibly starting in 789 when Beorhtric married Offa's daughter, Eadburh. Regardless, Ecgberht's exile occurred during Beorhtric's reign.

During his exile, Francia was under the rule of Charlemagne, who was known to support Offa's enemies. Another significant exile in Gaul at this time was Eadberht, who later became King of Kent. According to the later chronicler William of Malmesbury, Ecgberht used his time in Gaul to learn the arts of government, an experience that likely proved invaluable upon his return.

1.3. Accession to the Throne of Wessex

Beorhtric died in 802, leading to Ecgberht's return from exile and his accession to the throne of Wessex. His return was likely facilitated by the support of Charlemagne and potentially the papacy, indicating a significant shift in political alliances.

Upon his accession, Ecgberht immediately faced opposition from Mercia. On the very day of his coronation, the Hwicce, a people then part of Mercia, launched an attack under their ealdorman, Æthelmund. However, Æthelmund's forces were met and defeated by Weohstan, a Wessex ealdorman, who commanded troops from Wiltshire. Weohstan was reportedly Ecgberht's brother-in-law, having married his half-sister Alburga. While both Weohstan and Æthelmund perished in the battle, the Mercian challenge was repelled. For the next two decades, direct records of Ecgberht's relations with Mercia are scarce, suggesting that while he may not have held influence beyond Wessex's borders, he also never submitted to the overlordship of Cenwulf of Mercia, who dominated other southern English kingdoms. Cenwulf's charters notably omit the title "overlord of the southern English," possibly due to Wessex's preserved independence.

2. Expansion of Power and Establishment of Hegemony

The period following Ecgberht's early reign was characterized by a dramatic shift in power dynamics, as Wessex under his leadership aggressively expanded its territory and influence, culminating in an unprecedented level of dominance over Anglo-Saxon England.

2.1. Early Reign and Consolidation

The first two decades of Ecgberht's reign, from 802 to 825, are sparsely documented. During this time, he focused on consolidating his power within Wessex and maintaining its independence against the dominant Mercian kingdom. Although Mercia, under kings like Cenwulf, held significant sway over other southern English kingdoms, Ecgberht managed to keep Wessex free from their direct overlordship.

In 815, Ecgberht led a significant military campaign against the remaining British kingdom of Dumnonia, which encompassed what is now Cornwall. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that he ravaged the entirety of their territories, referred to as the West Welsh. The border between Wessex and Dumnonia had been pushed back to the River Tamar, which separates Devon and Cornwall, as early as 710 by King Ine. A charter from August 19, 825, indicates that Ecgberht was again campaigning in Dumnonia, potentially connected to a battle at Gafulford in 823 between the men of Devon and the Britons of Cornwall. These early campaigns established Wessex's military capability and began its westward expansion.

2.2. Battle of Ellandun and Conquest of the Southeast

In 821, King Cenwulf of Mercia died. His brother Ceolwulf I succeeded him but was deposed in 823 by Beornwulf of Mercia, a Mercian nobleman. It was also in 825 that one of the most important battles in Anglo-Saxon history took place, when Ecgberht decisively defeated Beornwulf of Mercia at Ellandun-now Wroughton, near Swindon. This battle marked the definitive end of Mercian domination over southern England. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recounts Ecgberht's swift exploitation of this triumph: he dispatched his son, Æthelwulf, along with his bishop, Ealhstan, and ealdorman, Wulfheard, to Kent with a substantial force. Æthelwulf successfully drove Baldred of Kent, the Mercian-appointed king of Kent, north across the River Thames. Subsequently, the peoples of Kent, Essex, Surrey, and Sussex all submitted to Æthelwulf. The Chronicle notes their submission was motivated by their being "wrongly forced away from his relatives" earlier, likely referring to Offa of Mercia's interventions when Ecgberht's father, Ealhmund, ruled Kent. This suggests that Ealhmund may have had connections throughout the southeastern kingdoms.

While the Chronicle implies Baldred was expelled immediately after Ellandun, a Kentish document dated March 826, still under Beornwulf's third regnal year, suggests that Beornwulf (as Baldred's overlord) retained authority in Kent at that time, indicating Baldred was likely still in power for a period. In Essex, Ecgberht expelled King Sigered of Essex, though the exact date is unclear, potentially as late as 829.

Historians suggest that Beornwulf was likely the aggressor at Ellandun, possibly taking advantage of Ecgberht's campaigns in Dumnonia in the summer of 825. Beornwulf's motivation might have been to preempt unrest in the southeast, where Wessex's dynastic ties to Kent posed a threat to Mercian authority.

The repercussions of Ellandun extended beyond the immediate decline of Mercian power in the southeast. In 825 (or possibly 826), the East Anglians sought Ecgberht's protection against Mercian attempts to reassert overlordship. In 826, Beornwulf invaded East Anglia and was slain. His successor, Ludeca, met the same fate in 827 during another invasion of East Anglia. These disasters for Mercia, coupled with Ecgberht's termination of Archbishop Wulfred of Canterbury's currency and his own minting of coins at Rochester and Canterbury, solidified West Saxon power throughout the southeast.

2.3. Conquest of Mercia and Bretwalda Title

In 829, Ecgberht advanced his conquests by invading Mercia itself, driving its king, Wiglaf of Mercia, into exile. This significant victory allowed Ecgberht to seize control of the London Mint, where he began issuing coins as the King of Mercia, marking his direct rule over the kingdom.

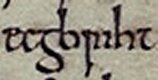

It was after this triumph that a West Saxon scribe, in a famous passage within the C manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, described Ecgberht as a bretwalda, a term generally interpreted as 'wide-ruler' or possibly 'Britain-ruler'. The relevant passage reads:

⁊ þy geare geeode Ecgbriht cing Myrcna rice ⁊ eall þæt be suþan Humbre wæs, ⁊ he wæs eahtaþa cing se ðe Bretenanwealda wæs.

In modern English, this translates to:

And the same year King Egbert conquered the kingdom of Mercia, and all that was south of the Humber, and he was the eighth king who was 'Wide-ruler'.

The Chronicle also names the previous seven bretwaldas, echoing the list of kings that the historian Bede identified as holding imperium, starting with Ælle of Sussex and concluding with Oswiu of Northumbria. This list is often considered incomplete by historians, as it notably omits powerful Mercian rulers such as Penda and Offa, who exerted significant dominance. The precise meaning of the title bretwalda has been extensively debated; some scholars view it as a term of "encomiastic poetry," signifying praise, while others argue it implied a concrete role of military leadership over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

2.4. Submission of Northumbria and Welsh Campaigns

Later in 829, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that Ecgberht received the submission of the Northumbrians at Dore, which is now a suburb of Sheffield. The Northumbrian king at this time was likely Eanred of Northumbria. A later chronicler, Roger of Wendover, provides a more aggressive account, stating that Ecgberht invaded and plundered Northumbria before Eanred submitted and paid tribute. While the Chronicle does not corroborate these details, Roger of Wendover is known to have incorporated Northumbrian annals into his work. However, the nature of Eanred's submission is sometimes questioned by historians, with some suggesting the meeting at Dore might have represented a mutual recognition of sovereignty rather than outright conquest.

In 830, Ecgberht led a successful expedition against the Welsh. This campaign was almost certainly aimed at extending West Saxon influence into the Welsh lands that had previously been within Mercia's sphere of control. This series of military and political achievements, culminating in the submission of Northumbria and the Welsh campaigns, marked the zenith of Ecgberht's power and established Wessex as the dominant force in Anglo-Saxon England.

3. Decline in Influence and Challenges

Despite Ecgberht's extensive conquests and the establishment of Wessex's hegemony, the latter part of his reign saw a reduction in his direct influence, primarily due to the resurgence of Mercian independence and the persistent threat of Viking incursions.

3.1. Re-establishment of Mercian Independence

In 830, Mercia regained its independence under King Wiglaf. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle simply states that Wiglaf "obtained the kingdom of Mercia again," but the most widely accepted explanation among historians is that this was the result of a Mercian rebellion against West Saxon rule. This re-establishment of Mercian independence marked the end of Ecgberht's fleeting direct dominion over all of southern England.

Evidence of Wiglaf's renewed autonomy quickly followed. Charters from this period indicate that Wiglaf exercised authority in Middlesex and Berkshire. Furthermore, a significant charter from 836 shows Wiglaf referring to "my bishops, duces, and magistrates," a group that included eleven bishops from the episcopate of Canterbury, even those from sees within West Saxon territory. This demonstrates Wiglaf's continued ability to convene such an influential group, an act the West Saxons, despite their power, were not known to replicate. It is also possible that Wiglaf brought Essex back into the Mercian orbit following his recovery of the throne. In East Anglia, King Æthelstan began minting his own coins, likely around 830, after Ecgberht's influence diminished with Wiglaf's return to power. This reassertion of East Anglian independence is understandable, as Æthelstan was likely responsible for the defeats and deaths of both Beornwulf and Ludeca.

Historians have explored the underlying reasons for Wessex's rapid rise and subsequent partial loss of its dominant position in the late 820s and early 830s. One plausible explanation attributes Wessex's initial successes, in part, to Carolingian support. The Franks had previously supported the return of Eardwulf of Northumbria in 808, making their backing for Ecgberht's accession in 802 a credible possibility. Even as late as Easter 839, shortly before Ecgberht's death, he was in communication with Louis the Pious, King of the Franks, to arrange safe passage to Rome, suggesting a continuing diplomatic relationship between Wessex and the Franks throughout the early 9th century.

However, the collapse of Rhenish and Frankish commercial networks in the 820s or 830s, coupled with a series of internal conflicts within the Frankish Empire beginning in February 830, may have prevented Louis the Pious from offering continued support to Ecgberht. This withdrawal of Frankish influence could have left East Anglia, Mercia, and Wessex to establish a new balance of power independent of external aid.

Despite the reduction in direct control, Ecgberht's military victories fundamentally reshaped the political map of Anglo-Saxon England. Wessex maintained firm control over the southeastern kingdoms, possibly with the exception of Essex, and Mercia never regained its overlordship of East Anglia. Ecgberht's conquests effectively ended the independent existence of the kingdoms of Kent and Sussex. These conquered territories were administered as a subkingdom, including Surrey and potentially Essex, with Ecgberht's son Æthelwulf ruling them. Although Æthelwulf was a subking, he maintained his own royal household, traveling throughout his domain. Charters issued in Kent described both Ecgberht and Æthelwulf as "kings of the West Saxons and also of the people of Kent." It was only after Æthelwulf's death in 858 that these southeastern kingdoms were fully integrated into Wessex, as indicated by his will. Mercia, however, remained a potential threat; Æthelwulf, as King of Kent, granted estates to Christ Church, Canterbury, likely to counteract any lingering Mercian influence there.

3.2. Conflicts with Vikings and in Cornwall

The latter part of Ecgberht's reign was marked by the increasing threat of Viking incursions. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle notes that Viking raids began as early as 793, with a terrifying account of the destruction of the church at Lindisfarne. These attacks intensified and became a major concern in the closing years of Ecgberht's rule.

In 836, Ecgberht suffered a defeat at Carhampton in Somerset at the hands of the Danes. However, he achieved a decisive victory two years later, in 838, at the Battle of Hingston Down in Cornwall. Here, Ecgberht's forces successfully defeated a combined army of Vikings and their allies, the West Welsh (Dumnonian Britons). While the Dumnonian royal line persisted for some time, this battle is often considered the effective end of the independence of one of the last remaining British kingdoms in the southwest.

The details of Anglo-Saxon expansion into Cornwall are not well-recorded, but place-name evidence provides some insight. The River Ottery, which flows east into the River Tamar near Launceston, appears to have served as a boundary. South of the Ottery, place names are predominantly Cornish, while to the north, they show stronger English influence, reflecting the extent of West Saxon settlement.

4. Succession and Death

Ecgberht strategically managed his succession, ensuring a smooth transition of power to his son, Æthelwulf, and his death marked the beginning of a secure lineage for the West Saxon royal house.

4.1. Securing the Succession

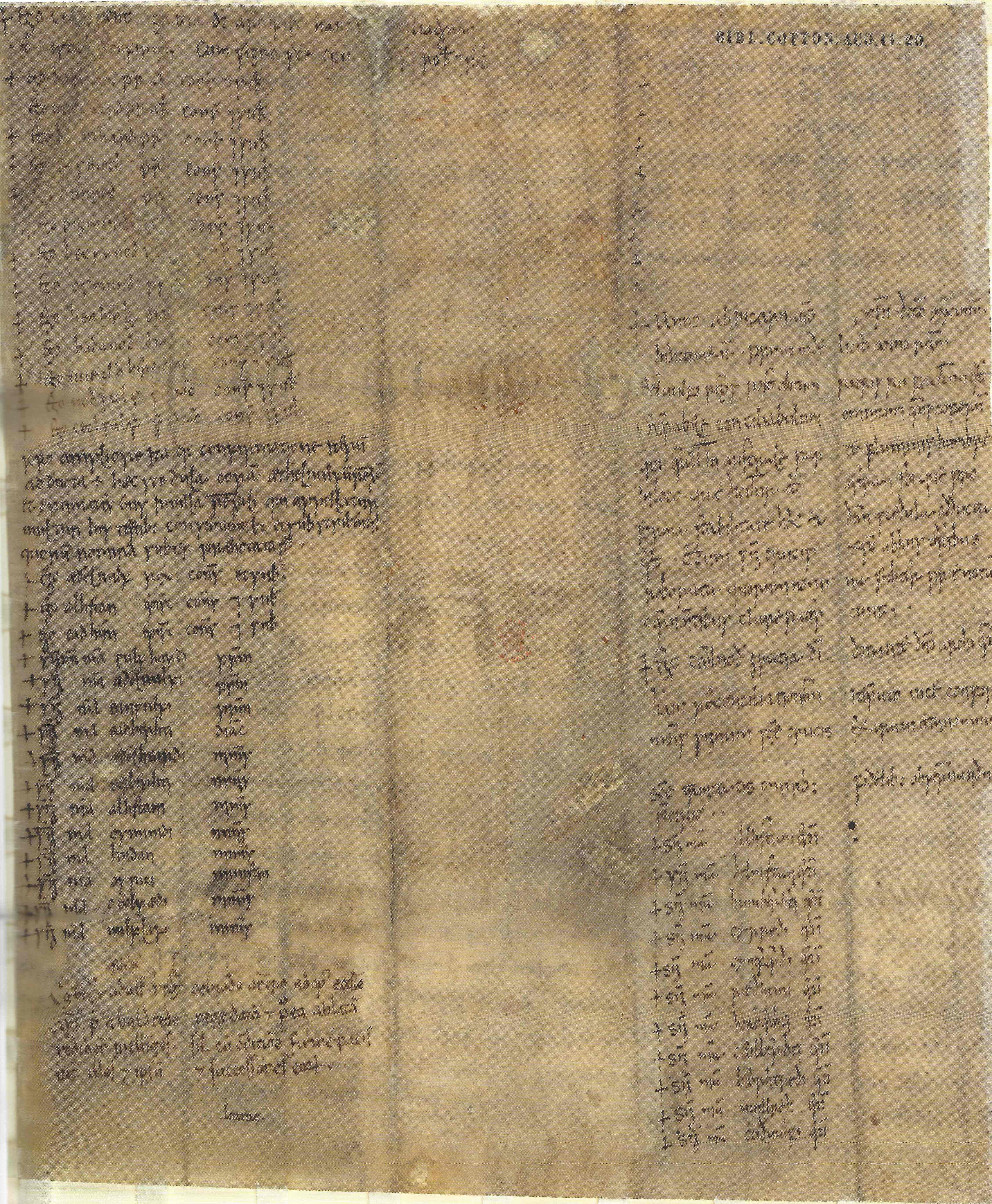

At a council held at Kingston upon Thames in 838, Ecgberht, along with his son Æthelwulf, made significant grants of land to the sees of Winchester and Canterbury. These grants were made in exchange for a crucial promise of support for Æthelwulf's claim to the throne. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Ceolnoth, also acknowledged Ecgberht and Æthelwulf as the lords and protectors of the monasteries under his control. These agreements, along with a later charter in which Æthelwulf confirmed church privileges, suggest that the church, recognizing Wessex's emerging political power, had strategically aligned itself with the new dynasty.

The support of influential churchmen was invaluable in consolidating West Saxon control and ensuring a peaceful succession for Ecgberht's line. Church figures were instrumental in consecrating kings at coronation ceremonies and often assisted in drafting wills that designated the royal heir. Both the record of the Council of Kingston and another charter from that year contain identical phrasing, stipulating that the grants were conditional upon "we ourselves and our heirs shall always hereafter have firm and unshakable friendships from Archbishop Ceolnoth and his congregation at Christ Church."

Although specific rival claimants to the throne are not named in historical records, it is highly probable that other descendants of Cerdic, the supposed progenitor of all Wessex kings, existed and might have contended for the kingdom. Ecgberht's successful efforts to secure Æthelwulf's untroubled succession was a notable achievement, given that the kingship of Wessex had frequently been contested among different branches of the royal family. Furthermore, Æthelwulf's prior experience ruling as a subking in the southeastern territories conquered by Ecgberht would have provided valuable preparation for his assumption of the main throne.

Ecgberht's will, as described in the will of his grandson, Alfred the Great, explicitly stipulated that land should be inherited only by male members of his family, preventing estates from being lost to the royal house through marriage. This measure reflects Ecgberht's understanding of the importance of personal wealth to a king, and his accumulated wealth, largely acquired through conquest, undoubtedly facilitated his ability to secure the crucial support of the southeastern church establishment.

4.2. Death and Burial

Ecgberht died in 839, likely of natural causes, and was buried in Winchester. This city became the preferred burial site for the West Saxon royal line, including his son Æthelwulf, his grandson Alfred the Great, and his great-grandson Edward the Elder. During the 9th century, Winchester began to show signs of urbanization, and the consistent royal burials there suggest the city's growing importance and high regard within the West Saxon kingdom.

Centuries later, after the Norman Conquest of England, Winchester Cathedral was constructed. Ecgberht's remains were exhumed and reinterred near the altar of Saint Swithun within the cathedral. During the English Civil War in the 17th century, soldiers under Oliver Cromwell reportedly used the bones, including those of Ecgberht, to smash the cathedral's stained-glass windows. These disturbed remains were subsequently mingled with those of other Anglo-Saxon kings, bishops, and even the Norman king William Rufus, on various mortuary chests. Later archaeological investigations have examined the commingled bones within these chests.

5. Legacy and Historical Assessment

Ecgberht's reign fundamentally reshaped the political landscape of Anglo-Saxon England, laying crucial foundations for future unification, though his achievements also faced limitations and subsequent challenges.

5.1. Foundations for English Unification

Ecgberht's pivotal role in unifying much of southern England under West Saxon rule cannot be overstated. His decisive victory at the Battle of Ellandun in 825 shattered Mercian supremacy and led to the direct control or submission of the southeastern kingdoms, including Kent, Essex, Surrey, and Sussex. The temporary subjugation of Mercia itself and the submission of Northumbria in 829 marked an unprecedented expansion of West Saxon power.

His designation as bretwalda by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, signifying 'wide-ruler' over Anglo-Saxon lands, highlights the extensive authority he wielded, even if its precise implications are debated by historians. While Ecgberht did not formally adopt the title of "King of England"-a title first explicitly used by his great-grandson, Æthelstan-his reign established a crucial precedent for a unified English kingdom. By bringing diverse Anglo-Saxon regions under a single West Saxon hegemony, Ecgberht fundamentally altered the political structure, creating a more cohesive and centralized power base from which later kings could pursue the complete unification of England. His efforts to secure a stable succession also contributed to the continuity of the West Saxon dynasty, which would ultimately achieve this goal.

5.2. Criticisms and Limitations

Despite his significant achievements, Ecgberht's rule also had its limitations. His direct dominance over Mercia proved temporary, as King Wiglaf successfully re-established Mercian independence in 830, indicating that Ecgberht's control was not fully solidified. This resurgence suggests that the unification achieved was more a hegemonic overlordship rather than a complete absorption of all kingdoms.

Furthermore, Ecgberht's reign coincided with the escalating threat of Viking invasions. Although he achieved notable victories against the Danes, such as at Hingston Down in 838, he was unable to permanently expel the raiders, and the Viking threat persisted and intensified in the decades following his death. The defeat at Carhampton in 836 also highlights the challenges he faced in defending his territories. While Ecgberht laid vital groundwork, the complete unification and defense of England against Viking incursions would fall to his successors, particularly Alfred the Great. These criticisms offer a balanced perspective, acknowledging the immense scope of his accomplishments while also recognizing the temporary nature of some of his conquests and the persistent external challenges that remained.