1. Names and Titles

Wu Zetian was known by various names and official titles throughout her life and posthumously, reflecting her changing status and self-proclaimed authority. In Classical Chinese, titles such as hou (后Chinese, "sovereign", "prince", "queen") or huangdi (皇帝Chinese, "imperial supreme ruler", "royal deity") are grammatically indeterminate in gender, allowing a woman to use titles typically associated with male rulers.

1.1. Birth and Personal Names

Wu Zetian was born with the personal name Wu Zhao (武照Chinese). Her birth name was often not formally recorded for women in her era. As a child, she was commonly referred to as Wu Meiniang (武媚娘Chinese), derived from the art name Wu Mei (武媚Chinese, meaning "glamorous") bestowed upon her by Emperor Taizong. Her family name, Wu (武Chinese), is a homophone for the second character in "parrot" (鹦鹉Chinese), leading to many stories and jokes using parrot imagery to refer to her and her clan. For instance, Emperor Gaozong's family name, Li (唐Chinese), is a homophone with a type of cat, which led to a story circulating about a cat eating a parrot at court, subtly referencing Wu and the Li clan.

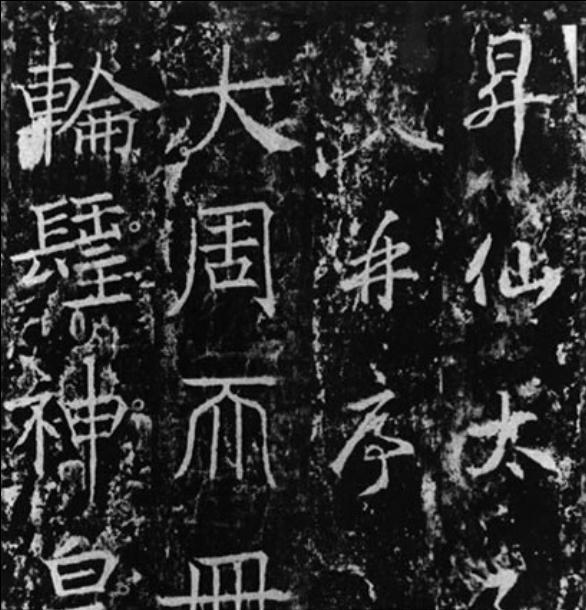

Upon her ascension to the throne in 690, Wu Zetian adopted a new personal name character, Zhao (曌Chinese). This character was one of several she invented, sometimes written as 瞾Chinese. The character 曌Chinese is composed of the characters Ming (明Chinese, "light" or "clarity") on top and Kong (空Chinese, "sky") on the bottom, implying that she would be like the light shining from the sky, symbolizing her supreme authority and legitimacy.

1.2. Official and Posthumous Titles

Wu Zetian held a progression of official ranks and honorific titles throughout her life:

- As Concubine to Emperor Taizong (637-649)**:

- Lady Wu (from 624, her birth)

- Talented Lady (才人Chinese; from 637), a 17th-rank consort.

- As Concubine and Empress to Emperor Gaozong (649-683)**:

- Imperial Concubine Zhaoyi (昭儀Chinese; from 650), the highest-ranking concubine of the second rank.

- Empress (皇后Chinese; from 655), the highest-ranking of the wives. This is the title of an empress consort.

- Heavenly Empress (天后Chinese; from 674), bestowed when Emperor Gaozong adopted the title "Heavenly Emperor" (天皇Chinese). This period was known as the "Two Saints" (二聖Chinese, Er Sheng) co-rule.

- As Empress Dowager (683-690)**:

- Empress Dowager Wu (武皇太后Chinese; from 683), when she became regent for her sons.

- During her reign as Empress Regnant of the Zhou dynasty (690-705)**:

- Holy Emperor (聖神皇帝Chinese; from 690)

- Holy Golden Emperor (金輪聖神皇帝Chinese; from 693)

- Holy Golden Goddess Emperor (越古金輪聖神皇帝Chinese; from 694)

- Holy Golden Emperor (金輪聖神皇帝Chinese; from 695)

- Emperor Tiance Jinlun (天策金輪大帝Chinese; from 695)

- Emperor Zetian Dasheng (則天大聖皇帝Chinese; from 705)

- Posthumous Titles (after 705)**:

- Empress Zetian Dasheng (則天大聖皇后Chinese; from 705), her initial posthumous title, reverting her status to empress consort.

- Heavenly Empress (天后Chinese; from 710)

- Holy Empress (大聖天后Chinese; from 710)

- Empress of Heaven (天后聖帝Chinese; from 712)

- Holy Empress (聖后Chinese; from 712)

- Empress Zetian (則天皇后Chinese; from 716)

- Holy Empress Zetianshun (則天順聖皇后Chinese; from 749)

Wu Zetian was the only woman in Chinese history to assume the title huangdi (皇帝Chinese), meaning "emperor" or "empress regnant." This was a significant break from historical precedent, as the position of huangdi was traditionally male. She also became one of the few women in Chinese history, alongside Empress Dowager Liu of the Song dynasty, to wear a yellow robe, which was usually reserved solely for the emperor.

2. Background and Early Life

Wu Zetian's early life was marked by unique educational opportunities and an early entry into the imperial court, which shaped her ambition and capabilities.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Wu Zetian was born in the seventh year of the reign of Emperor Gaozu of Tang (624 AD). Her exact birthplace is debated among scholars, with some suggesting Wenshui County, Bingzhou (modern-day Taiyuan, Shanxi), others Lizhou (modern-day Guangyuan, Sichuan), and some the imperial capital of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an). The year of her birth is most commonly accepted as 624, deduced from the age at death given in the New Book of Tang (compiled 1045-1060), though the Old Book of Tang (compiled 941-945) suggests 623, and the Zizhi Tongjian (compiled 1065-84) aligns with 624 based on her age at death and entry into the palace. Dates provided here are in the Julian calendar.

Her father, Wu Shiyue, came from a relatively well-off family involved in the timber business. He gained prominence during the founding of the Tang dynasty. During the final years of Emperor Yang of Sui, Li Yuan (the future Emperor Gaozu of Tang) frequently stayed at the Wu household, forming close ties with the family while holding appointments in Hedong and Taiyuan. After Li Yuan overthrew Emperor Yang and established the Tang dynasty, he rewarded the Wu family generously with grain, land, clothing, and wealth. Wu Shiyue held a succession of senior ministerial posts, including governorships of Yangzhou, Lizhou, and Jingzhou (modern-day Jiangling County, Hubei).

Her mother, Lady Yang, came from the influential Yang family, distant relatives of the imperial family of the Sui dynasty. Lady Yang was the daughter of Yang Da, a prime minister during the Sui dynasty. Wu Zetian had two elder half-brothers, Wu Yuanqing and Wu Yuanshuang, from her father's first wife, and two full sisters, one of whom was Lady Wu Shun (later Lady of Han), and a younger sister who married Guo Xiaoshen.

2.2. Education and Upbringing

Uncommonly for women of her time, Wu Zetian was encouraged by her parents to read and pursue an education. She delved into a wide range of subjects including music, calligraphy, literature, history, and politics, as well as other governmental affairs. This early exposure to intellectual pursuits and statecraft contributed significantly to her intellectual development and shaped her ambition. When she was summoned to the palace at a young age, her mother, Lady Yang, wept bitterly. Wu Zetian, however, remained composed, famously remarking, "How do you know that it is not my fortune to meet the Son of Heaven?" This response reportedly made her mother understand her ambitious spirit.

2.3. As Concubine to Emperor Taizong

At the age of 14, in 637, Wu Zetian entered the imperial palace as an imperial concubine (a lesser wife) of Emperor Taizong of Tang. She was given the title of cairen (才人Chinese), which was the 5th rank in the Tang dynasty's nine-rank system for imperial consorts. During this period, she also served as a type of secretary, which allowed her to continue her education.

Despite her intellect and beauty, Consort Wu did not appear to be greatly favored by Emperor Taizong, though she did have sexual relations with him at one point. According to her own account, she once impressed him with her fortitude: "Emperor Taizong had a horse with the name 'Lion Stallion,' and it was so large and strong that no one could get on its back. I was a lady-in-waiting attending Emperor Taizong, and I suggested to him, 'I only need three things to subordinate it: an iron whip, an iron hammer, and a sharp dagger. I will whip it with the iron whip. If it does not submit, I will hammer its head with the iron hammer. If it still does not submit, I will cut its throat with the dagger.' Emperor Taizong praised my bravery. Do you really believe that you are qualified to dirty my dagger?"

During Taizong's illness, the Crown Prince Li Zhi (the future Emperor Gaozong), Taizong's ninth son, met and became enamored with Wu. Upon Emperor Taizong's death in 649, because Wu Zetian had not produced any children with him, she was, according to custom, confined to Ganye Temple (感業寺Chinese) to serve as a Buddhist nun for the remainder of her life.

3. Rise to Power

The period after Emperor Taizong's death was pivotal for Wu Zetian, as she re-entered the imperial court and navigated intense power struggles that ultimately led to her unprecedented rise as empress.

3.1. Return to the Palace under Emperor Gaozong

In early 650, on the anniversary of Emperor Taizong's death, Emperor Gaozong went to Ganye Temple to offer incense. He and Wu Zetian saw each other and both wept, rekindling their earlier affection. At this time, Gaozong was not particularly fond of his wife, Empress Wang, and instead favored his concubine, Pure Consort Xiao. Empress Wang, seeing Gaozong's interest in Wu Zetian, hoped that bringing a new concubine into the palace would divert the emperor's attention away from Consort Xiao. She secretly instructed Wu Zetian to let her hair grow back and then welcomed her to the palace. Some modern historians, including Bo Yang, based on the birth of Consort Wu's oldest son Li Hong in 652, fixed the date of this incident as 650, though 651 is also a possibility. Some modern historians, however, dispute this traditional account, suggesting Wu Zetian might never have truly left the imperial palace and could have had an affair with Gaozong while Taizong was still alive.

Wu Zetian quickly surpassed Consort Xiao as Gaozong's favorite. She was granted the title of Zhaoyi (昭儀Chinese), the highest-ranking concubine of the second rank.

3.2. Struggle with Empress Wang and Consort Xiao

By 654, both Empress Wang and Consort Xiao had lost favor with Gaozong and formed an alliance against Wu Zetian, but to no avail. Wu Zetian gave birth to her first child, a son named Li Hong, in 652, followed by another son, Li Xian, in 653. Neither of these sons was immediately considered for the heir apparent position, as Gaozong had designated his eldest son, Li Zhong (born to a low-ranking Consort Liu), as heir at the request of Empress Wang and her uncle, Chancellor Liu Shi.

In 654, Wu Zetian gave birth to a daughter, who died shortly after birth. This incident became a central controversy in her rise. Wu Zetian accused Empress Wang of murder, alleging that Wang had been seen near the child's room, a claim corroborated by alleged eyewitnesses. Gaozong was led to believe that Wang, motivated by jealousy, had killed the child. Empress Wang lacked an alibi and could not clear her name. While traditional folklore, often portraying Wu as a ruthless and power-hungry woman, suggests Wu Zetian herself killed her child to frame Wang, scientifically credible forensic pathology information is absent. Other theories include Wang indeed killing the child out of jealousy, or the child dying from natural causes such as asphyxiation or crib death, possibly exacerbated by poor ventilation and coal heating leading to carbon monoxide poisoning. Regardless of the true cause, Wu Zetian successfully blamed Empress Wang.

An angry Gaozong decided to depose Wang and replace her with Wu Zetian, but he needed the support of his chancellors. He met with his uncle, Zhangsun Wuji, the head chancellor, and repeatedly brought up Wang's childlessness as an excuse for deposition, but Zhangsun repeatedly diverted the conversation. Subsequent visits by Wu Zetian's mother, Lady Yang, and her ally, official Xu Jingzong, to seek Zhangsun's support were also unsuccessful.

In the summer of 655, Wu Zetian accused Empress Wang and her mother, Lady Liu, of using witchcraft, leading Gaozong to bar Lady Liu from the palace and demote Wang's uncle, Liu Shi. A faction of officials supporting Wu Zetian, including Li Yifu, Xu Jingzong, Cui Yixuan (崔義玄Chinese), and Yuan Gongyu (袁公瑜Chinese), began to form. That autumn, Gaozong summoned chancellors Zhangsun Wuji, Li Ji, Yu Zhining, and Chu Suiliang. Li Ji feigned illness and did not attend. Chu Suiliang vehemently opposed Wang's deposition, while Zhangsun Wuji and Yu Zhining remained silent to show disapproval. Chancellors Han Yuan and Lai Ji also opposed the move. When Gaozong asked Li Ji again, he famously responded, "This is your family matter, Your Imperial Majesty. Why ask anyone else?"

Gaozong resolved to act. Chu Suiliang was demoted to commandant at Tan Prefecture (modern Changsha, Hunan). Both Empress Wang and Consort Xiao were deposed and placed under arrest, and Wu Zetian was made empress. Later that year, Gaozong considered releasing them, but Empress Wu, fearing their return, ordered their deaths. They were reportedly tortured, with their limbs severed and bodies thrown into wine jars to ensure they "got drunk to the bones." After their deaths, Wu Zetian reportedly suffered from nightmares, frequently seeing Wang and Xiao as vengeful spirits. This led Gaozong to remodel Daming Palace into Penglai Palace to alleviate her fears, but the nightmares persisted, causing Wu Zetian and Gaozong to frequently reside in the eastern capital Luoyang rather than Chang'an.

4. Reign as Empress Consort

As empress consort, Wu Zetian progressively gained immense influence over the governance of the empire. She effectively co-ruled with Emperor Gaozong, consolidating her power through systematic purges and strategic political maneuvers.

4.1. "Two Saints" Co-Rule with Emperor Gaozong

After becoming empress in 655, Wu Zetian and her allies began to retaliate against officials who had opposed her ascension. In 656, on Xu Jingzong's advice, Emperor Gaozong deposed Li Zhong, his first-born son, from being heir apparent and designated Empress Wu Zetian's son, Li Hong, as Crown Prince.

Empress Wu Zetian then systematically targeted her opponents. In 657, Xu Jingzong and Li Yifu (both now chancellors) falsely accused Han Yuan and Lai Ji of complicity with Chu Suiliang in treason. The three, along with Liu Shi, were demoted to remote prefectures. In 659, Xu Jingzong accused Zhangsun Wuji of plotting treason with low-level officials. Zhangsun Wuji was exiled and later forced to commit suicide. Xu Jingzong further implicated Chu Suiliang, Liu Shi, Han Yuan, and Yu Zhining in the plot. Chu Suiliang, who had died in 658, was posthumously stripped of titles, and his sons were executed. Orders were also issued to execute Liu Shi and Han Yuan. After this, no official dared to criticize the emperor. In 660, Li Zhong, fearing for his life, sought advice from fortune tellers, which Wu Zetian used as a pretext to have him exiled and placed under house arrest.

By 660, Emperor Gaozong began to suffer from a debilitating illness, characterized by painful headaches and loss of vision, generally thought to be hypertension-related. He increasingly relied on Empress Wu Zetian to make rulings on daily petitions from officials. Her authority soon rivaled Gaozong's.

In 664, Empress Wu Zetian's extensive interference in governance angered Gaozong. She had engaged the Taoist sorcerer Guo Xingzhen (郭行真Chinese) in witchcraft, an act that had contributed to Empress Wang's downfall. The eunuch Wang Fusheng (王伏勝Chinese) reported this to Gaozong, who consulted Chancellor Shangguan Yi. Shangguan Yi suggested deposing Wu Zetian and began drafting an edict. However, Wu Zetian learned of the plot, confronted Gaozong, and tearfully pleaded her case. Gaozong, unable to depose her, blamed Shangguan Yi. As Shangguan Yi and Wang Fusheng had served on Li Zhong's staff, Wu Zetian had Xu Jingzong falsely accuse them and Li Zhong of treason. Shangguan Yi, Wang Fusheng, and Shangguan Yi's son, Shangguan Tingzhi (上官庭芝Chinese), were executed, and Li Zhong was forced to commit suicide. Shangguan Tingzhi's infant daughter, Shangguan Wan'er, and her mother became slaves in the inner palace; Shangguan Wan'er later became Wu Zetian's trusted secretary.

Thereafter, Wu Zetian and Gaozong were referred to as the "Two Saints" (二聖Chinese, Er Sheng) both within the palace and throughout the empire, signifying her substantial and overt authority in co-ruling. The Later Jin historian Liu Xu, in Old Book of Tang, noted that "She assisted the emperor in governing for decades, with authority and power no different from the emperor."

4.2. Elimination of Political Opponents and Imperial Relatives

Wu Zetian's consolidation of power also involved ruthless purges within her own extended family and the imperial Li clan. Her mother, Lady Yang, was made the Lady of Rong, and her older widowed sister, Lady of Han, also gained favor. Her half-brothers Wu Yuanqing and Wu Yuanshuang, and cousins Wu Weiliang and Wu Huaiyun, despite their poor relationship with Lady Yang, were promoted. However, when Wu Weiliang offended Lady Yang at a family feast by disdainfully stating their promotions were solely due to Empress Wu Zetian, Wu Zetian used this as a pretext to have them demoted to remote prefectures, ostensibly to show modesty, but in reality to avenge her mother. Wu Yuanqing and Wu Yuanshuang died in effective exile.

Lady of Han died in or before 666. Emperor Gaozong then made her daughter, Lady Helan (賀蘭氏Chinese, later Lady of Wei), a concubine, but out of fear of Empress Wu Zetian's displeasure, he did not immediately bring her into the palace. Wu Zetian, aware of this, allegedly poisoned Lady of Wei by placing poison in food offerings made by Wu Weiliang and Wu Huaiyun, then blamed them for her niece's death. Wu Weiliang and Wu Huaiyun were executed.

In 670, Lady Yang died. By imperial decree, all officials and their wives attended her wake. At Wu Zetian's request, her father, Wu Shiyue (posthumously honored as Duke of Zhou), and Lady Yang were posthumously elevated to Prince and Princess of Taiyuan.

Helan Minzhi (賀蘭敏之Chinese), the son of Lady of Han, was given the surname Wu and allowed to inherit the title of Duke of Zhou. However, Empress Wu Zetian grew wary of him as he apparently suspected her of murdering his sister, Lady of Wei. In 671, Helan Minzhi was accused of disobeying mourning regulations during Lady Yang's mourning period and of raping the daughter of official Yang Sijian (楊思儉Chinese), who had been chosen as the crown princess for Li Hong. On Wu Zetian's orders, Helan Minzhi was exiled and either executed or committed suicide in exile.

In 675, as Emperor Gaozong's illness worsened, he considered formally appointing Empress Wu Zetian as regent. However, Chancellor Hao Chujun and official Li Yiyan both opposed this, and she was not formally made regent. Nevertheless, her power was such that she surpassed Emperor Gaozong in influence, making key decisions on governmental and border matters and appointing civil and military officials.

Also in 675, Wu Zetian's displeasure with Gaozong's aunt, Princess Changle, led to a series of tragedies. Princess Changle's daughter, who was married to Wu Zetian's third son, Li Xiǎn, the Prince of Zhou, was accused of unspecified crimes, arrested, and starved to death. Princess Changle and her husband, General Zhao Gui (趙瓌Chinese), were exiled. Later that month, Li Hong, the Crown Prince-who had urged Wu Zetian to reduce her influence and requested that his half-sisters (Consort Xiao's daughters) be allowed to marry-died suddenly. Traditional historians generally believed Wu Zetian poisoned Li Hong. At her request, Li Xiǎn, then Prince of Yong, was made crown prince. Consort Xiao's son, Li Sujie, and another of Gaozong's sons, Li Shangjin, were repeatedly accused by Wu Zetian and subsequently demoted.

Wu Zetian's relationship with Li Xiǎn soon deteriorated. Li Xiǎn became unsettled by rumors that he was not Wu Zetian's biological son but rather the son of her sister, Lady of Han. Empress Wu Zetian grew furious upon learning of his fears. In 678, the poet Luo Binwang criticized Empress Wu Zetian's governmental involvement, leading to his dismissal and imprisonment. Furthermore, the sorcerer Ming Chongyan (明崇儼Chinese), respected by both Wu Zetian and Gaozong, had stated Li Xiǎn was unsuitable for the throne and was assassinated in 679. Wu Zetian suspected Li Xiǎn was behind the assassination. In 680, Li Xiǎn was accused of crimes, and a large number of weapons were found in his palace. Empress Wu Zetian formally accused him of treason and Ming Chongyan's assassination. Despite Emperor Gaozong's desire to forgive Li Xiǎn, Empress Wu Zetian insisted on his punishment. Li Xiǎn was deposed, exiled, and forced to commit suicide in exile.

At Empress Wu Zetian's request, his younger brother, Li Xiǎn (李顯Chinese, later renamed Li Zhe), was named crown prince. In 681, Princess Taiping, Wu Zetian's daughter, was married in a grand ceremony. In 682, official Feng Yuanchang lamented Empress Wu Zetian's power and suggested reducing it. Gaozong, afraid of her, did nothing. Upon learning of Feng Yuanchang's advice, Wu Zetian accused him of corruption and demoted him.

5. Empress Dowager and Regency

After Emperor Gaozong's death in 683, Wu Zetian, as empress dowager, wielded supreme power as regent, effectively ruling the empire through her sons and preparing for her direct imperial rule. This period was marked by her decisive actions against perceived threats and the establishment of a notorious secret police.

5.1. Deposition of Emperor Zhongzong and Enthronement of Emperor Ruizong

Upon Emperor Gaozong's death in 683, Li Zhe ascended the throne as Emperor Zhongzong. Gaozong's will explicitly stipulated that Li Zhe should ascend immediately and consult Empress Wu Zetian on all important matters, effectively granting her senior authority. Wu Zetian, now empress dowager (皇太后Chinese, huangtaihou), automatically gained full power, including the authority to remove and install emperors.

Emperor Zhongzong, however, immediately showed signs of defying his mother, largely influenced by his wife, Empress Wei. He appointed his father-in-law, Wei Xuanzhen (韋玄貞Chinese), as prime minister and attempted to give a mid-level office to his wet nurse's son, despite stern opposition from Chancellor Pei Yan. At one point, Zhongzong remarked to Pei Yan, "What would be wrong even if I gave the empire to Wei Xuanzhen? Why do you care about Shizhong so much?"

Pei Yan reported this to Empress Dowager Wu Zetian. After planning with Pei Yan, Liu Yizhi, and generals Cheng Wuting (程務挺Chinese) and Zhang Qianxu (張虔勖Chinese), Wu Zetian decisively deposed Emperor Zhongzong within six weeks of his reign. Zhongzong was reduced to the title of Prince of Luling and exiled, and Wei Xuanzhen was charged with treason and sent into seclusion. Wu Zetian then enthroned her youngest son, Li Dan, the Prince of Yu, as Emperor Ruizong. Emperor Ruizong was a puppet ruler, held as a virtual prisoner in the inner quarters, never moving into the imperial quarters or appearing at official functions. Wu Zetian firmly controlled the imperial court, and officials reported directly to her, with Ruizong not even nominally approving official actions. Wu Zetian also sent General Qiu Shenji (丘神勣Chinese) to Li Xiǎn's place in exile and forced Li Xiǎn to commit suicide.

5.2. Implementation of Secret Police and Purges

During Emperor Ruizong's nominal reign, Wu Zetian was the absolute ruler. She did not hide behind screens or curtains; her reign was fully recognized. Soon after Ruizong took the throne, Wu Zetian initiated major renamings of governmental offices and banners, and elevated Luoyang's status to a coequal capital. At her nephew Wu Chengsi's suggestion, she expanded the shrine of the Wu ancestors and gave them greater posthumous honors, making it the size of the emperor's ancestral shrine.

In 686, Wu Zetian offered to return imperial authority to Emperor Ruizong, but he declined, knowing she did not genuinely intend to relinquish power. She continued to exercise imperial authority. Meanwhile, she established copper mailboxes outside imperial government buildings to encourage secret reporting on suspected opponents. Wu Zetian personally read all reports of betrayal. This system led to the rise of secret police officials like Suo Yuanli, Zhou Xing, and Lai Junchen, who carried out systematic false accusations, torture, and executions. They were known for their cruel methods, such as the "Dying Swine's Melancholy" (死猪愁Chinese), a torture device that inflicted immense pain. The historian Sima Guang, in his Zizhi Tongjian, commented that while Wu Zetian excessively used official titles to control people, she would depose or execute anyone she found incompetent, demonstrating her firm grasp on power and shrewd judgment in selecting talented officials. Throughout the Zizhi Tongjian descriptions of Wu Zetian's reign, Sima Guang referred to her as "the Empress Dowager," implicitly refusing to recognize her as empress regnant, though he used her era names.

5.3. Li Jingye's Rebellion and Its Suppression

In 684, Li Ji's grandson, Li Jingye, the Duke of Ying, who had been disaffected by his own exile, launched a significant rebellion in Yang Prefecture (揚州Chinese, modern Yangzhou, Jiangsu). The rebellion initially gained popular support, but Li Jingye progressed slowly and failed to capitalize on this momentum. Meanwhile, Chancellor Pei Yan suggested to Empress Dowager Wu Zetian that she restore imperial authority to Emperor Ruizong, arguing this would cause the rebellion to collapse. This angered Wu Zetian, who accused Pei Yan of complicity with Li Jingye and had him executed, along with other officials who tried to speak on his behalf. She dispatched General Li Xiaoyi (李孝逸Chinese) to suppress the rebellion. Despite initial setbacks, Li Xiaoyi, urged by his assistant Wei Yuanzhong, eventually crushed Li Jingye's forces. Li Jingye fled and was killed during his flight.

In 688, Wu Zetian prepared for sacrifices to the deity of the Luo River in Luoyang. She summoned senior members of the Tang imperial Li clan to Luoyang, sparking fears that she intended to eliminate them. Imperial princes Li Zhen and his son Li Chong preemptively rebelled in Yu Prefecture (豫州Chinese, modern Zhumadian, Henan) and Bo Prefecture (博州Chinese, modern Liaocheng, Shandong). However, the other princes were not yet ready and did not join. Forces sent by Empress Dowager Wu Zetian swiftly crushed the rebellion. Wu Zetian used this opportunity to arrest Emperor Gaozong's granduncles, Li Yuanjia (李元嘉Chinese) the Prince of Han, Li Lingkui (李靈夔Chinese) the Prince of Lu, and Princess Changle, along with many other members of the Li clan, forcing them to commit suicide. Princess Taiping's husband, Xue Shao, was also implicated and starved to death. In subsequent years, politically motivated massacres of officials and Li clan members continued.

6. Founding the Wu Zhou Dynasty and Imperial Reign

In 690, Wu Zetian formally declared herself emperor, establishing the Wu Zhou dynasty and ruling China directly. This marked an unprecedented era in Chinese history under a female sovereign.

6.1. Ascension to the Throne and Establishment of Wu Zhou

Wu Zetian took the final step to become empress regnant in 690, establishing the Zhou dynasty, named after the historical Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BC). To legitimize her claim, she strategically used religious prophecies, particularly the apocryphal Commentary on the Meanings of the Prophecies About the Divine Sovereign in the Great Cloud Sutra (Dayunjing Shenhuang Shouji Yishu). This commentary, based on the Great Cloud Sutra, featured a conversation where the Buddha foretold a bodhisattva's reincarnation in a woman's body to rule a country. Wu Zetian's Buddhist supporters meticulously propagated this text. She even identified herself as the incarnation of male Buddhist divinities like Maitreya and Vairocana to transcend gender limitations and gain popular support, while persuading the Confucian establishment and circumventing the "Five Impediments" traditionally restricting women from political and religious power.

On 14 October 690, after various officials and commoners submitted petitions urging her to take the throne, Wu Zetian formally approved the requests. She changed the state's name to Zhou on 16 October, and on 19 October, she took the throne as Empress Regnant with the title Holy Emperor (聖神皇帝Chinese). Emperor Ruizong, her son, was deposed and made crown prince with the atypical title Huangsi (皇嗣Chinese). This act officially interrupted the Tang dynasty, making Wu Zetian the first (and only) woman to reign over China as empress regnant. Her decision to found a new dynasty, rather than merely act as regent, was a culmination of her power politics and was little opposed at the time.

6.2. Early Imperial Reign (690-696)

In the early years of her direct rule, Wu Zetian elevated the status of Buddhism above Taoism. She officially sanctioned Buddhism by building temples named Dayun Temple (大雲寺Chinese) in each prefecture of the two capitals, Luoyang and Chang'an, and appointed nine senior monks as dukes. She enshrined seven generations of Wu ancestors at the imperial ancestral temple, while continuing to offer sacrifices to the Tang emperors Gaozu, Taizong, and Gaozong.

The issue of imperial succession became a central concern. While she initially named Li Dan (the former Emperor Ruizong) as crown prince, her nephew Wu Chengsi and others advocated for a Wu clan member to inherit the throne, arguing that an emperor named Wu should pass the throne to a Wu. When chancellors Cen Changqian and Ge Fuyuan sternly opposed this, they, along with fellow chancellor Ouyang Tong, were executed. Wu Zetian ultimately declined to make Wu Chengsi crown prince. However, a commoner, Wang Qingzhi (王慶之Chinese), who had led a petition drive for Wu Chengsi, was allowed free access to the palace. When Wang Qingzhi became a nuisance, Wu Zetian ordered official Li Zhaode to punish him, which Li Zhaode exploited to beat Wang Qingzhi to death. Li Zhaode then persuaded Wu Zetian to keep Li Dan as crown prince, emphasizing the closer relationship of a son over a nephew and the implications for Gaozong's worship if a Wu family member became emperor. Wu Zetian agreed. At Li Zhaode's warning that Wu Chengsi was becoming too powerful, Wu Zetian stripped Wu Chengsi of his chancellor authority, granting him largely honorific titles without real power.

The power of the secret police officials continued to increase during this period. However, their influence began to be curbed around 692, when Lai Junchen's attempt to execute chancellors Ren Zhigu, Di Renjie, Pei Xingben, and other officials failed due to Di Renjie's secret petition. After this incident, particularly at the urging of Li Zhaode, Zhu Jingze, and Zhou Ju (周矩Chinese), the waves of politically motivated massacres decreased, though they did not end entirely. Wu Zetian utilized the imperial examination system to find talented individuals from poor or non-aristocratic backgrounds to stabilize her regime.

In 692, Wu Zetian commissioned General Wang Xiaojie to attack the Tibetan Empire. Wang Xiaojie successfully recaptured the four garrisons of the Western Regions-Kucha, Yutian, Kashgar, and Suyab-which had fallen to the Tibetan Empire in 670.

In 693, Wu Zetian's trusted lady-in-waiting, Wei Tuan'er (韋團兒Chinese), who disliked Li Dan, falsely accused his wife, Crown Princess Liu, and Consort Dou of witchcraft. Wu Zetian had Crown Princess Liu and Consort Dou killed. Li Dan, fearing for his own life, did not dare to speak of them. Wei Tuan'er later planned to falsely accuse Li Dan as well, but someone informed on her, leading to her execution. Wu Zetian had Li Dan's sons demoted in their princely titles and barred officials from meeting Li Dan after officials Pei Feigong (裴匪躬Chinese) and Fan Yunxian (范雲仙Chinese) were executed for secretly meeting him. Further accusations of treason against Li Dan led to an investigation by Lai Junchen, who tortured Li Dan's servants. When one servant, An Jincang, proclaimed Li Dan's innocence and cut open his own belly as an oath, Wu Zetian ordered doctors to save his life and instructed Lai Junchen to end the investigation, thus saving Li Dan. In 694, Li Zhaode, who had become powerful after Wu Chengsi's removal, was himself removed from power.

Around this time, Wu Zetian became highly impressed with a group of mystic individuals, including the hermit Wei Shifang (briefly given a chancellor title) who claimed to be over 350 years old, an old Buddhist nun claiming to be a Buddha capable of predicting the future, and a non-Han man claiming to be 500 years old. Wu Zetian briefly claimed to be and adopted the cult imagery of Maitreya to build popular support for her reign. In 695, after the imperial meeting hall (明堂Chinese) and the Heavenly Hall (天堂Chinese) were burned by Huaiyi (who was jealous of Wu Zetian's new lover, imperial physician Shen Nanqiu), Wu Zetian grew angry at these mystics for failing to predict the fire. The old nun and her students were arrested and enslaved, Wei Shifang committed suicide, and the non-Han man fled. Huaiyi was put to death. After this incident, she appeared to pay less attention to mysticism and became even more dedicated to state affairs.

6.3. Middle Imperial Reign (696-701)

Wu Zetian's administration faced significant challenges on the western and northern borders. In spring 696, she sent an army led by Wang Xiaojie and Lou Shide against the Tibetan Empire, but they were soundly defeated by Tibetan generals. As a result, Wang was demoted to commoner rank and Lou to a low-level official, though both were eventually restored to general positions. In April of the same year, Wu Zetian recast the Nine Tripod Cauldrons, symbols of ultimate power in ancient China, to reinforce her authority.

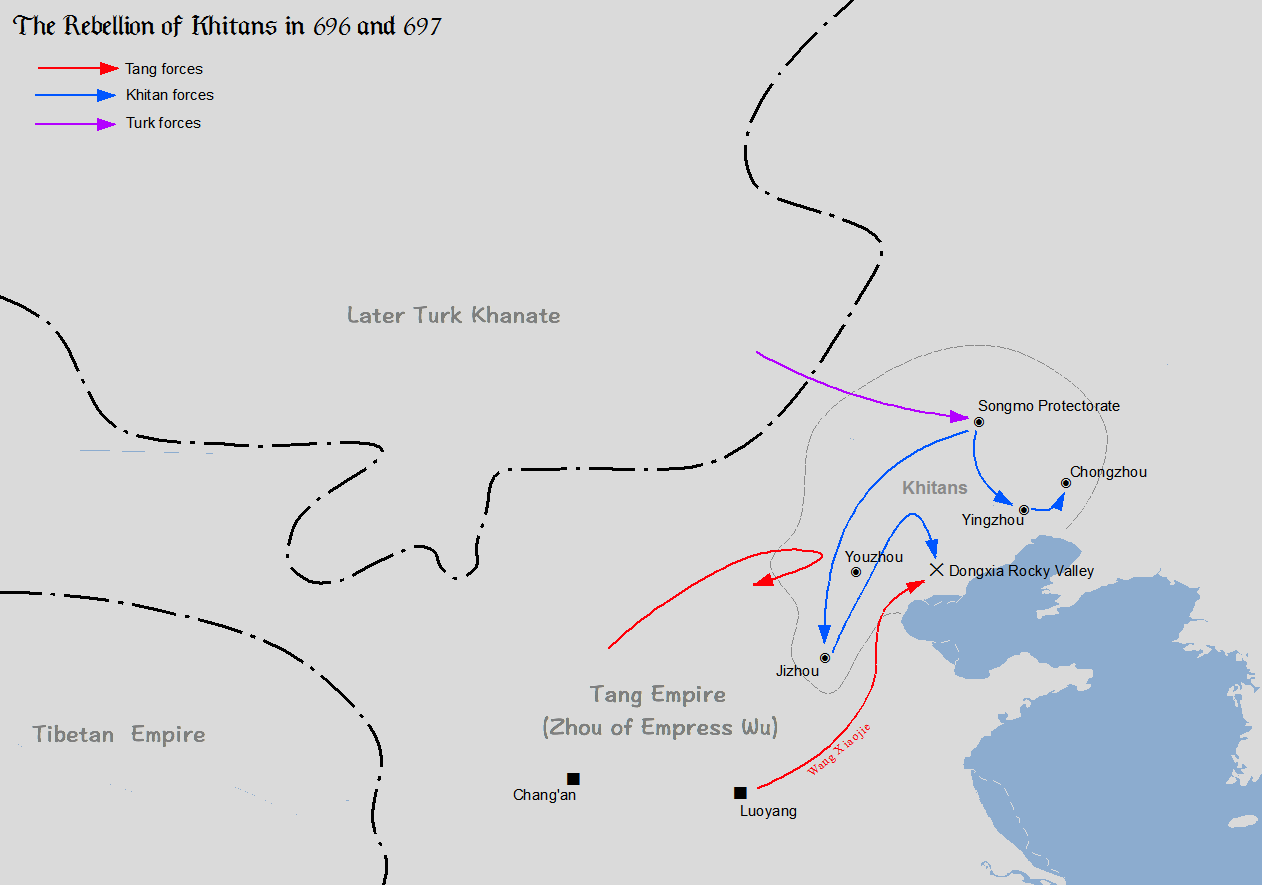

A much more serious threat arose in summer 696. The Khitan chieftains Li Jinzhong and Sun Wanrong, brothers-in-law, rebelled due to the mistreatment of the Khitan people by the Zhou official Zhao Wenhui (趙文翽Chinese), prefect of Ying Prefecture (營州Chinese, modern Zhaoyang County, Liaoning). Li Jinzhong assumed the title of Wushang Khan (無上可汗Chinese). Armies sent by Wu Zetian to suppress the rebellion were defeated by Khitan forces, which then attacked Zhou territory. Meanwhile, Qapaghan Qaghan of the Second Turkic Khaganate offered to submit to Zhou while also launching attacks against both Zhou and Khitan. These attacks included one against the Khitan base during the winter of 696, shortly after Li Jinzhong's death, which led to the capture of Li Jinzhong's and Sun Wanrong's families and temporarily halted Khitan operations against Zhou.

Sun Wanrong, after reorganizing Khitan forces, launched further attacks on Zhou territory, achieving many victories, including a battle where Wang Shijie was killed. Wu Zetian attempted to stabilize the situation by making peace with Ashina Mochuo on costly terms: the return of Turkic people who had submitted to Zhou and provisions of seeds, silk, tools, and iron. In summer 697, Mochuo launched another attack on the Khitan base, causing Khitan forces to collapse and Sun Wanrong to be killed in flight, thus ending the Khitan threat.

Also in 697, Lai Junchen, who had at one point lost power but then returned to power, falsely accused Li Zhaode (who had been pardoned) of crimes, and then planned to falsely accuse Li Dan, Li Zhe, the Wu clan princes, and Princess Taiping of treason. The Wu clan princes and Princess Taiping acted first against him, accusing him of crimes, and he and Li Zhaode were executed together. After Lai's death, the secret police's reign largely ended. Gradually, many of the victims of Lai and the other secret police officials were exonerated posthumously. Meanwhile, around this time, Wu began relationships with two new lovers-the brothers Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong, who became honored within the palace and were eventually created dukes.

Around 698, Wu Chengsi and another nephew of Wu Zetian's, Wu Sansi, the Prince of Liang, repeatedly made attempts to have officials persuade Wu Zetian to make one of them crown prince-again arguing that an emperor should pass the throne to someone of the same clan. But Di Renjie, who by now had become a trusted chancellor, firmly opposed the idea, and proposed that Li Zhe be recalled instead. He was supported in this by fellow chancellors Wang Fangqing and Wang Jishan, as well as Wu Zetian's close advisor Ji Xu, who further persuaded the Zhang brothers to support the idea. In spring 698, Wu agreed and recalled Li Zhe from exile. Soon, Li Dan offered to yield the crown prince position to Li Zhe, and Wu created Li Zhe crown prince. She soon changed his name back to Li Xiǎn and then Wu Xian.

Later, Ashina Mochuo demanded a Tang dynasty prince for marriage to his daughter, part of a plot to join his family with the Tang, displace the Zhou, and restore Tang rule over China, under his influence. When Wu sent a member of her own family, grandnephew Wu Yanxiu (武延秀Chinese), to marry Mochuo's daughter instead, he rejected him. Mochuo had no intention to cement the peace treaty with a marriage. Instead, when Wu Yanxiu arrived, he detained him and then launched a major attack on Zhou, advancing as far south as Zhao Prefecture (趙州Chinese, in modern Shijiazhuang, Hebei) before withdrawing.

In 699, the Tibetan threat ceased. Emperor Tridu Songtsen, unhappy that Gar Trinring was monopolizing power, slaughtered Trinring's associates when Trinring was away from Lhasa. He then defeated Trinring in battle, and Trinring committed suicide. Gar Tsenba and Trinring's son, Lun Gongren (論弓仁Chinese), surrendered to Zhou. After this, the Tibetan Empire underwent internal turmoil for several years, and there was peace for Zhou in the border region.

Also in 699, Wu, realizing that she was growing old, feared that after her death, Li Xian and the Wu clan princes would not have peace with each other. She made him, Li Dan, Princess Taiping, Princess Taiping's second husband Wu Youji (a nephew of hers), the Prince of Ding, and other Wu clan princes to swear an oath to each other.

6.4. Late Imperial Reign (701-705)

As Wu Zetian grew older, Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong became increasingly powerful, and even the princes of the Wu clan sought their favour. She increasingly relied on them to handle the affairs of state. This was secretly discussed and criticized by her grandson Li Chongrun, the Prince of Shao (Li Xian's son), granddaughter Li Xianhui (李仙蕙Chinese) the Lady Yongtai (Li Chongrun's sister), and Li Xianhui's husband Wu Yanji (武延基Chinese) the Prince of Wei (Wu Zetian's grandnephew and Wu Chengsi's son). The discussion was leaked, and Zhang Yizhi reported this to Wu Zetian, who ordered all three to commit suicide. The Zizhi Tongjian asserted that Li Chongrun was forced to commit suicide, while the Old Book of Tang and the New Book of Tang asserted he was caned to death on Wu Zetian's orders. Li Xianhui's tombstone, written after Emperor Zhongzong's restoration in 705, suggests she died the day after her brother and husband while pregnant, leading to theories of miscarriage or difficult birth in grief.

Despite her age, Wu Zetian continued to be interested in finding talented officials and promoting them. People she promoted in her old age included Cui Xuanwei and Zhang Jiazhen.

By 703, Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong had become resentful of Wei Yuanzhong, who by now was a senior chancellor, for dressing down their brother Zhang Changyi (張昌儀Chinese) and rejecting the promotion of another brother, Zhang Changqi (張昌期Chinese). They also were fearful that if Wu died, Wei would find a way to execute them, and therefore accused Wei and Gao Jian (高戩Chinese), an official favored by Princess Taiping, of speculating on Wu's old age and death. They initially got Wei's subordinate Zhang Shuo to agree to corroborate the charges, but once Zhang Shuo was before Wu, he instead accused Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong of forcing him to bear false witness. As a result, Wei, Gao, and Zhang Shuo were exiled, but escaped death.

7. Major Policies and Reforms

Wu Zetian's long and influential period of rule saw significant administrative, social, economic, cultural, and military policies and reforms.

7.1. Reform of the Imperial Examination System

Wu Zetian's reign was a pivotal moment for the imperial examination system. Before her, Tang rulers were exclusively male members of the Li family. As a woman outside the Li family, Wu Zetian needed an alternative power base, and reforms to the imperial examinations became central to her plan to create a new class of elite bureaucrats from humbler origins.

She significantly expanded and refined the system, increasing the pool of candidates by allowing commoners and gentry, previously disqualified by their background, to take the test. In 693, she greatly increased the importance of this method of recruiting government officials. Both palace and military examinations were created under her rule, focusing solely on merit. This effectively improved the nation's bureaucracy by ensuring that competence, rather than family connections, became a key feature of the civil service. This shift also provided increased opportunities for people from the North China Plain to gain government representation, in contrast to the entrenched northwestern aristocratic families, many of whom she suppressed. The successful candidates recruited through the examination system formed an influential elite within her government, and the long-term historical consequences of her promotion of these previously disenfranchised individuals remain a subject of scholarly debate.

7.2. Religious Policies

Wu Zetian was a strong patron of Buddhism, elevating it to the status of state religion. She commissioned grand Buddhist art, most notably the colossal Vairocana Buddha statue (circa 675) in the Fengxian cave of the Longmen Grottoes, which is said to have features based on her likeness. She also established Dayun Temples across the country to propagate Buddhist teachings.

Her patronage of Buddhism was often strategically used to legitimize her rule. For instance, in 690, she had monks compose the apocryphal Commentary on the Meanings of the Prophecies About the Divine Sovereign in the Great Cloud Sutra (Dayunjing Shenhuang Shouji Yishu), which described a conversation between the Buddha and the Devi of Pure Radiance, foretelling a bodhisattva's reincarnation in a woman's body to rule a country. She also identified herself as an incarnation of male Buddhist divinities like Maitreya and Vairocana to transcend gender limitations and gain public support. William Dalrymple notes that she used Buddhist texts brought from Nalanda University by Xuanzang to legitimize her rule, leading to a substantial import of Indian ideas. Under her, the slaughter of animals was strictly prohibited, and she incorporated Indian principles, such as those from the Ashokan edicts, into her governance, including the presence of Indian faith healers and astrologers in her court.

While favoring Buddhism, Wu Zetian also engaged with Taoism. She participated in important religious rituals such as the tou long on Mount Song and the feng and shan sacrifices on Mount Tai. In an unprecedented move during Emperor Gaozong's sacrifices to heaven and earth in 666, Wu Zetian offered sacrifices after him, conspicuously linking her with China's most sacred traditional rites and demonstrating her claim to the Mandate of Heaven. In 700, she conducted the tou long Daoist expiatory rite. These ceremonies served both political and religious motives, further consolidating her political life and displaying her divine mandate.

7.3. Literary and Cultural Patronage

Wu Zetian actively supported scholars and literary figures, fostering a vibrant cultural environment. Toward the end of Gaozong's life, she engaged a group of mid-level officials known as the "North Gate Scholars" (北門學士Chinese), including Yuan Wanqing (元萬頃Chinese), Liu Yizhi, Fan Lübing, Miao Chuke (苗楚客Chinese), Zhou Simao (周思茂Chinese), and Han Chubin (韓楚賓Chinese). They worked inside the palace, north of the imperial government buildings, and composed various works on her behalf, such as the Biographies of Notable Women (列女傳Chinese), Guidelines for Imperial Subjects (臣軌Chinese), and New Teachings for Official Staff Members (百僚新誡Chinese). Wu Zetian sought their advice to subtly redirect power away from the chancellors.

On 28 January 675, Wu Zetian submitted "Twelve Suggestions" (建言十二事Chinese) for governance, which Emperor Gaozong praised and adopted. One suggestion mandated that Laozi's Tao Te Ching be required reading for imperial university students, and another advocated a three-year mourning period for a mother's death in all cases.

In 690, Wu Zetian's cousin's son Zong Qinke submitted a number of modified Chinese characters intended to highlight her greatness. She adopted them, choosing one, Zhao (曌Chinese), as her formal personal name. This character visually combines Ming (明Chinese, "light" or "clarity") and Kong (空Chinese, "sky"), implying her radiance from the heavens. These "Zetian characters" were part of her broader ideological program. Zong Qinke created these new characters in December 689, and Wu Zetian chose 曌 as her given name, which became her taboo name upon her ascension. Some sources assert this character was actually written 瞾. While some also assert her original given name was Zhao and she only changed the written character in 689, this is not confirmed by the Old Book of Tang or New Book of Tang. Her grandson Li Chongrun (originally Li Chongzhao), changed his name to observe naming taboo for her.

Her court was a hub of literary creativity. Forty-six of her poems are collected in the Complete Tang Poems, and 61 essays under her name are recorded in the Quan Tangwen (Collected Tang Essays). Many of her writings served political ends, but one notable poem laments her mother's death, expressing profound despair. Wu Zetian sponsored works like the Zhuying ji (Collection of Precious Glories), an anthology of her court's poetry. The final stylistic development of the "new style" poetry, the regulated verse (jintishi), by Song Zhiwen and Shen Quanqi, also took place during her reign. The development of what is considered characteristic Tang poetry is traditionally ascribed to Chen Zi'ang, one of her ministers.

Literary allusions to Wu Zetian often carry complex connotations, from depicting a woman who inappropriately overstepped her bounds to highlighting hypocrisy (e.g., preaching compassion while being politically ruthless). For centuries, traditional establishments used Wu Zetian as an example of negative consequences when a woman held power. However, later interpretations, such as those during Mao Zedong's era, attempted to rehabilitate her image as a great unifier, reflecting shifting political narratives.

7.4. Social and Economic Policies

Wu Zetian's reign was characterized by efforts to maintain social stability and economic prosperity. She came to power during a period of relative contentment, good administration, and rising living standards in China, and she largely continued these trends. She was committed to ensuring that free, self-sufficient farmers could work their own land. To this end, she periodically re-implemented and adjusted the juntian (equal-field system) using updated census figures to ensure fair land allocations.

Many of her policies were popular and garnered support for her rule. Her various edicts, including those known as her "Acts of Grace," aimed to satisfy the needs of the lower classes through acts of relief. She widened recruitment to government service, allowing previously excluded gentry and commoners to enter official ranks, and provided generous promotions and pay raises for lower-ranking officials. The period saw no widespread peasant rebellions, and the population numbers remained stable, suggesting that civilian life was relatively stable and prosperous under her rule.

7.5. Military and Foreign Relations

Wu Zetian pursued assertive military and diplomatic strategies that expanded the Chinese empire and engaged with various neighboring powers. The fubing system of self-supportive soldier-farmer colonies, which provided local militia and labor services, allowed her to maintain her armed forces at reduced expense.

Her military campaigns led to the significant expansion of the Chinese empire, extending its reach far into Central Asia. Efforts to expand against Tibet and in the northwest were less consistently successful. She engaged in a series of wars on the Korean Peninsula, initially allying with Silla against Goguryeo. After Goguryeo's defeat in 668, Chinese forces occupied former Goguryeo territory. However, Silla resisted the imposition of Chinese rule and, by forming alliances with remnants of Goguryeo and Baekje, successfully expelled Tang forces from the peninsula. Some historians suggest Silla's success was partly due to Wu Zetian's shift in focus towards Tibet and inadequate support for forces on the Korean peninsula. In 694, Wu Zetian's forces decisively defeated a Tibetan-Western Turk alliance and retook the Four Garrisons of Anxi. The Tibetan Empire later experienced internal turmoil after its ruler killed the powerful general Gar Trinring in 699, which brought several years of peace to Zhou's border region.

In 651, shortly after the Muslim conquest of Persia, the first Arab ambassador arrived in China during her period of influence, marking the beginning of formal diplomatic contacts.

8. Removal from Power and Death

The final events of Wu Zetian's reign were characterized by her failing health, increasing reliance on her male favorites, and a court conspiracy that led to her forced abdication and the restoration of the Tang dynasty.

8.1. The Shenlong Coup

In autumn 704, accusations of corruption began to be leveled against Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong, as well as their brothers. While Zhang Tongxiu (張同休Chinese) and Zhang Changyi (張昌儀Chinese) were demoted, Wu Zetian, following the suggestion of Chancellor Yang Zaisi, did not remove Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong. Subsequently, Chancellor Wei Anshi renewed charges of corruption against the Zhang brothers.

In winter 704, Wu Zetian became seriously ill for a period, and only the Zhang brothers were allowed to see her; the chancellors were not. This led to widespread speculation that Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong were plotting to seize the throne, and repeated accusations of treason arose. Once her condition improved, Cui Xuanwei advocated that only Li Xian and Li Dan be permitted to attend to her, a suggestion she did not accept. Further accusations against the Zhang brothers by Huan Yanfan and Song Jing prompted Wu Zetian to allow Song Jing to investigate, but she issued a pardon for Zhang Yizhi before the investigation was completed, derailing it.

By spring 705, Wu Zetian was gravely ill again. A conspiracy led by loyal Tang officials, including Zhang Jianzhi, Jing Hui, and Yuan Shuji, planned a coup to eliminate the Zhang brothers and restore the Tang dynasty. They secured the involvement of generals Li Duozuo, Li Zhan (李湛Chinese), and Yang Yuanyan (楊元琰Chinese), as well as Chancellor Yao Yuanzhi, and gained agreement from Li Xian.

On 20 February 705, the conspirators launched their coup. They killed Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong and surrounded Changsheng Hall (長生殿Chinese), where Wu Zetian was residing. They informed her that the Zhang brothers had been executed for treason and then forced her to yield the throne to Li Xian.

8.2. Abdication, Final Days, and Burial

On 21 February 705, an edict was issued in Wu Zetian's name, making Li Xian regent. The next day, 22 February, another edict in her name formally passed the throne to him. On 23 February, Li Xian officially retook the throne, becoming Emperor Zhongzong for his second reign. The following day, under heavy guard, Wu Zetian was moved to the subsidiary palace, Shangyang Palace (上陽宮Chinese), while still honored with the title of Empress Regent Zetian Dasheng (則天大聖皇帝Chinese). On 3 March, the restoration of the Tang dynasty was celebrated, formally ending the Wu Zhou dynasty after 15 years.

Wu Zetian died on 16 December 705, at the age of 82. Pursuant to a final edict issued in her name, she was no longer referred to as empress regnant but instead as "Empress Consort Zetian Dasheng" (則天大聖皇后Chinese). Her last wishes included reverting her title to empress consort and rehabilitating the families of Empress Wang and Consort Xiao, as well as those of Chu Suiliang and Han Yuan. She also famously requested that her tombstone remain blank.

In 706, Wu Zetian's son Emperor Zhongzong had her interred in a joint burial with her husband, Emperor Gaozong, at the Qianling Mausoleum, located near the capital Chang'an on Mount Liang. Emperor Zhongzong also buried at Qianling his brother Li Xian, son Li Chongrun, and daughter Li Xianhui (李仙蕙Chinese) (posthumously honored as Princess Yongtai)-all victims of Wu Zetian's wrath.

The "Wordless Stele" (無字碑Chinese) at Qianling Mausoleum is a 21 ft (6.3 m) tall, 98 t blank tablet. Its lack of inscription has been subject to various interpretations: some say Wu Zetian believed her achievements were too great to be summarized, others that she left it blank for future generations to judge her, or that she could not decide whether to be buried as a Tang empress or a Zhou emperor. Despite multiple attempts at grave robbery throughout history, Qianling Mausoleum remains remarkably intact, distinguishing it from many other imperial tombs.

9. Historical Assessment and Legacy

Wu Zetian's historical assessment is profoundly mixed, acknowledging both her remarkable achievements and the controversies surrounding her actions.

9.1. Positive Aspects of Her Rule

Wu Zetian is often praised for her political acumen and effective governance. She was known for her ability to select talented officials, often through the expanded imperial examination system, which broadened access to government positions beyond the traditional aristocracy and fostered a more meritocratic bureaucracy. Her promotions and pay raises for lower-ranking officials contributed to social mobility.

During her tenure, China saw significant imperial expansion into Central Asia, and while her military campaigns on the Korean Peninsula had mixed results, her assertive foreign policy contributed to China's standing as a world power. Her reign also brought a period of internal stability and economic prosperity, characterized by a well-run administration, rising living standards, and notably, no major peasant rebellions. She supported agricultural productivity, including re-implementing the equal-field system and adjusting taxes, which benefited commoners.

Wu Zetian was a significant patron of culture and the arts. Her support for scholars, literary figures (like the North Gate Scholars), and the establishment of intellectual academies enriched Chinese cultural development. Her promotion of Buddhism also led to grand artistic and architectural projects, such as the Longmen Grottoes. Even traditional historians, who often vilified her, conceded her exceptional talent in identifying and employing capable individuals, many of whom later contributed to the flourishing "Kaiyuan Golden Age" under Emperor Xuanzong.

9.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite her achievements, Wu Zetian faced strong condemnation from traditional and some modern historians, largely due to her methods of acquiring and maintaining power, which often clashed with Confucian ideals. Her most severe criticisms include:

- Ruthless Purges and Alleged Infanticide**: She is accused of systematically eliminating political opponents and members of the imperial Li clan who posed a threat to her authority. These purges led to widespread fear and human rights abuses, often carried out by her secret police apparatus and cruel officials like Lai Junchen and Zhou Xing, who were known for using torture. The controversial death of her infant daughter, attributed by many to Wu Zetian herself to frame Empress Wang, remains a prominent example of her alleged cruelty.

- Use of Torture and Secret Police**: The establishment and extensive use of a fearsome secret police, which employed torture and false accusations, created a climate of terror at court.

- Relationships with Male Favorites**: Her relationships with male favorites, such as Xue Huaiyi and the Zhang brothers, were heavily criticized by Confucian historians as scandalous and a sign of moral decay, suggesting that these favorites gained undue influence and contributed to her decline in later years.

- Overstaffing and Corruption**: Some historians argue that her broad recruitment methods and generous promotions sometimes led to overstaffing and various forms of corruption within the bureaucracy.

- Usurpation of the Throne**: Her ultimate act of declaring herself emperor and establishing the Wu Zhou dynasty was seen by many traditional scholars as a grave transgression against the dynastic order and the patriarchal norms of Chinese society. Her reign, particularly her methods, was often compared to that of the notorious Empress Lü Zhi of the Han dynasty, leading to the collective term "Lu Wu" (呂武Chinese).

9.3. Long-term Impact and Historical Significance

Wu Zetian's reign left a unique and complex imprint on Chinese history. As the only legitimate female emperor, she profoundly challenged traditional notions of gender and leadership.

Her most enduring institutional legacy is arguably the significant expansion and refinement of the imperial examination system. By opening up government positions to a broader range of social classes based on merit rather than aristocratic birth, she fundamentally altered the structure of the Chinese bureaucracy and fostered greater social mobility, laying groundwork that persisted for centuries. This weakened the power of the old aristocracy and cultivated a new class of loyal officials.

Her strong patronage of Buddhism also had a lasting impact, elevating its status and leading to significant artistic and scholarly developments. Although the Wu Zhou dynasty was brief and the Tang dynasty was restored, her 15 years as empress regnant deeply influenced subsequent political structures, cultural perceptions, and the historical discourse on female leadership in China. While often vilified by later Confucian scholars, her reign demonstrated that a woman could effectively govern a vast empire, maintaining stability and driving progress, an unprecedented feat that continues to fascinate and divide historians.

10. Family

Wu Zetian had six children with Emperor Gaozong: four sons and two daughters. Her immediate family played significant roles, often tragically, in her political narrative.

- Sons**:

- Li Hong (李弘Chinese; 652-675): The eldest son, initially made Crown Prince. He was intelligent and kind, often advocating for his half-sisters and against his mother's increasing power. He died suddenly at the age of 23; traditional historians widely believe he was poisoned by Wu Zetian.

- Li Xian (李賢Chinese; 655-684): The second son, known for his literary talent, replaced Li Hong as Crown Prince. He was later deposed and exiled by Wu Zetian due to suspicions of treason and rumors about his birth. He was forced to commit suicide in exile.

- Li Xiǎn (李顯Chinese; 656-710): The third son, he ascended the throne briefly after Gaozong's death but was quickly deposed by Wu Zetian for perceived weakness and defiance. He was restored to the throne in 705 after the Shenlong Coup and reigned until his death in 710.

- Li Dan (李旦Chinese; 662-716): The youngest son, he became a puppet emperor after Zhongzong's deposition. He later yielded the throne to Wu Zetian when she declared her own dynasty. He was restored to power as Emperor Ruizong after Zhongzong's death in 710.

- Daughters**:

- Princess Anding (An Ding Si Gongzhu) (安定思公主Chinese; 654): Her first daughter, who died in infancy. This death became a central point of controversy in Wu Zetian's rise to power, with accusations that Wu Zetian killed her to frame Empress Wang.

- Princess Taiping (太平公主Chinese; 665-713): Her second daughter, a powerful and influential figure in her own right, often compared to her mother in ambition and political acumen. She played a significant role in court politics during her mother's later reign and the subsequent reigns of her brothers, eventually being forced to commit suicide by Emperor Xuanzong.

Wu Zetian also had a complex relationship with her extended family:

- Lady Yang** (楊氏Chinese; died 670): Her mother, who gained the title Lady of Rong.

- Lady of Han** (韓國夫人Chinese; died c. 666): Her older sister, who was rumored to have had an affair with Emperor Gaozong and allegedly bore Li Xian.

- Lady of Wei** (魏國夫人Chinese; died c. 666): The daughter of Lady of Han, allegedly poisoned by Wu Zetian.

- Helan Minzhi** (賀蘭敏之Chinese; 642-671): Son of Lady of Han, adopted into the Wu clan, but later exiled and killed by Wu Zetian's order.

- Wu Chengsi** (武承嗣Chinese; died 698): Her nephew, a prominent political figure who strongly advocated for a Wu family member to succeed Wu Zetian.

- Wu Sansi** (武三思Chinese; died 707): Another nephew, also influential in court politics, especially during Wu Zetian's later years.

11. In Popular Culture

Wu Zetian's extraordinary life and controversial reign have made her a compelling figure in popular culture, interpreted in various novels, films, and television dramas.

Her story has inspired numerous novels:

- Empress by Lin Yutang

- Wu by Jonathan Clements

- Empress by Shan Sa

- Cairen Wu Zhao (才人武曌Chinese) by Su Tong

She is a central character in many films:

- The Empress Wu Tse-tien (1963, Hong Kong) starring Li Li-hua.

- The Detective Dee film series, where she is portrayed by Carina Lau as a powerful and astute empress (2010, 2013, 2018).

Wu Zetian has been extensively depicted in television dramas, particularly in China and East Asia:

- Wu Zetian (1995, China), a well-known series starring Liu Xiaoqing.

- Secret History of Empress Wu (2011, China), featuring multiple actresses portraying her at different life stages, including Yin Tao, Liu Xiaoqing, and Siqin Gaowa.

- The Empress of China (2014-2015, China), a lavish production starring Fan Bingbing.

- She also appears in Korean historical dramas, such as Yeon Gaesomun (2006-2007) and Dae Jo-yeong (2006-2007).

Her influence extends to other media, including mention in the BBC television series Sherlock in the episode "The Blind Banker," and as a leader for the Chinese civilization in video games like Civilization II (1996), Civilization V (2010), and Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings (1999).

12. Era Names

Wu Zetian's reign was marked by a frequent change in era names, reflecting various political and symbolic shifts during her rule.

| Zhou dynasty (690-705): Convention: use personal name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Temple names | Family name and first name | Period of reign | Era names and their associated dates |

| None | Wǔ Zhào(武曌Chinese) | 690-705 | |