1. Overview

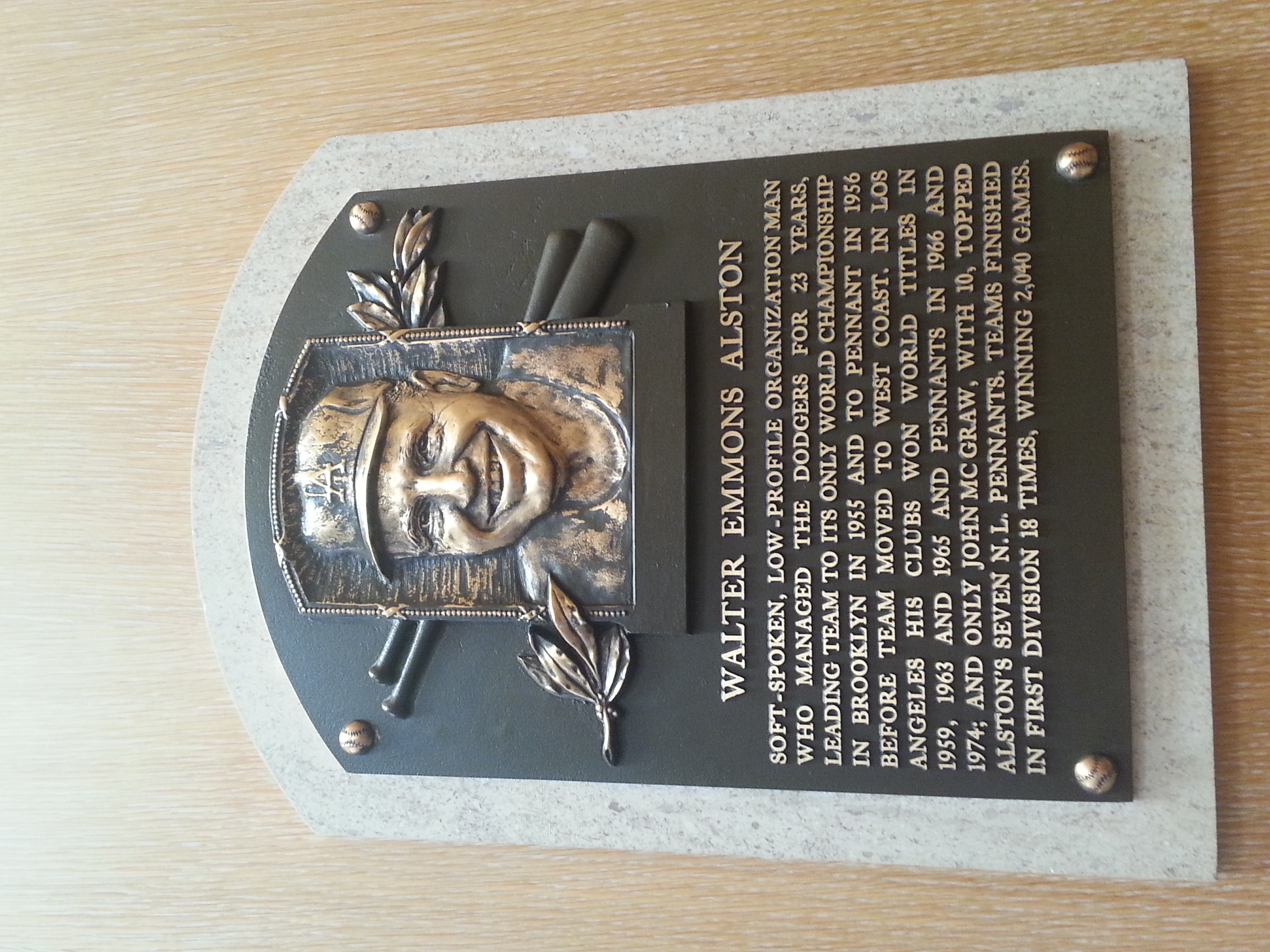

Walter Emmons Alston (December 1, 1911 - October 1, 1984), widely known by his nickname "Smokey," was an American baseball manager in Major League Baseball. He is best recognized for his extensive tenure managing the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers from 1954 through 1976, a period during which he famously signed 23 consecutive one-year contracts with the team. Alston is considered one of baseball's greatest managers, distinguished by his calm and reserved demeanor, which earned him the moniker "the Quiet Man."

Throughout his 23 seasons as a major league manager, Alston led Dodger teams to seven National League pennants and secured four World Series championships. Notably, the 1955 title was the only one won while the club was still based in Brooklyn. He retired with over 2,000 career wins and was honored as Manager of the Year six times. Additionally, he managed National League All-Star teams to seven victories. Alston's jersey number 24 was retired by the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1977. In 1983, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, but due to a heart attack and subsequent hospitalization, he was unable to attend his induction ceremony. He never fully recovered and passed away in Oxford, Ohio, on October 1, 1984.

2. Early life

Walter Alston's early life was rooted in rural Ohio, where he developed his athletic talents and pursued higher education before embarking on his professional baseball journey.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Walter Emmons Alston was born on December 1, 1911, in Venice, Ohio. He spent much of his childhood on a farm in Morning Sun, Ohio, before his family relocated to Darrtown, Ohio, when he was a teenager. During his time as a pitcher at Milford Township High School in Darrtown, he earned the nickname "Smokey" due to the impressive speed of his fastball.

After graduating from high school in 1929, Alston married his long-time girlfriend, Lela Vaughn Alexander, the following year. In 1935, he earned a degree in industrial arts and physical education from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Alston recalled facing financial challenges during his college years, stating that he paid his way through school by playing pool. He was a distinguished athlete at the university, earning a letter for three years in both basketball and baseball.

2.2. Playing career

Alston's professional playing career was brief at the Major League level but extensive in the minor leagues, where he gained valuable experience that would shape his future as a manager.

He began his minor league baseball career as an infielder, playing for the Greenwood Chiefs in 1935 and the Huntington Red Birds in 1936. During the 1936 season with Huntington, he displayed significant power, hitting 35 home runs in 120 games. Alston's sole Major League game occurred on September 27, 1936, with the St. Louis Cardinals, where he substituted for Johnny Mize at first base. He famously described his brief MLB stint to a reporter by saying, "Well, I came up to bat for the Cards back in '36, and Lon Warneke struck me out. That's it." In his two fielding chances at first base, he committed one error.

Following his brief MLB appearance, Alston returned to the minor leagues. In 1937, he split the season between the Houston Buffaloes and Rochester Red Wings, achieving a combined batting average of .229. He played for the Portsmouth Red Birds in 1938, where he finished the season with a .311 average and 28 home runs, contributing to Portsmouth's only Middle Atlantic League championship. Alston returned to Portsmouth in 1940, hitting 28 home runs and serving as a player-manager for part of the season. He continued as a player-manager for the next two seasons with the Springfield Cardinals, even making seven appearances as a pitcher in 1942. In 1943, he returned to Rochester as a first baseman and third baseman before moving to the Trenton Packers, where he was a player-manager in 1944 and 1945. The opportunity in Trenton, a minor league farm club of the Brooklyn Dodgers, was offered to him by Branch Rickey, the executive who had initially signed him as a player with St. Louis.

After his two seasons with Trenton, Alston took on a significant role as player-manager for the Nashua Dodgers of the Class-B New England League. This team holds historical importance as the first U.S.-based integrated professional baseball team in the twentieth century. Alston managed pioneering Black Dodgers prospects Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella, leading Nashua to a New England League title in 1946. Alston later stated that he did not focus on racial issues, but rather on how much these players would benefit the team, demonstrating his pragmatic approach to integration.

The following season, Alston led the Pueblo Dodgers to the Western League title. He made his final professional playing appearances in two games that season. Over his 13-season minor league playing career, Alston accumulated a .295 batting average with 176 home runs. However, in Class AA, which was the highest minor league classification through 1945, he hit only .239 in 535 at-bats.

3. Managerial career

Walter Alston's managerial career spanned decades, beginning in the minor leagues and culminating in a highly successful and enduring tenure with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, marked by numerous championships and a quiet, consistent leadership style.

3.1. Minor leagues

Alston's managerial success began in the minor leagues, where he honed his skills and developed players for the Dodgers organization. In 1948, he managed the St. Paul Saints, a Dodgers Class AAA affiliate, to an 86-68 win-loss record. The team finished in third place, 14 games behind an Indianapolis Indians team managed by Al López. That year, Alston again managed Roy Campanella, who was integrating the American Association. Alston faced criticism from the media for playing Campanella, with some suggesting the catcher was merely there to integrate the league. Despite this, Campanella hit 13 home runs in 35 games, and fans were dismayed when he was called up to the Dodgers. The 1949 Saints finished with a 93-60 record, and four of their players collected over 90 runs batted in. The team secured first place, half a game ahead of Indianapolis. During the baseball off-season, Alston worked as a teacher in Darrtown.

From 1950 to 1953, Alston managed another Dodgers AAA affiliate, the Montreal Royals of the International League. Under his leadership, the team consistently performed well, winning between 86 and 95 games each season. The 1951 and 1952 Montreal Royals notably won International League pennants. Furthermore, Montreal won the Governors' Cup playoff tournament in both 1951 and 1953. Alston's significant contributions to the league were recognized many years later when he was inducted into the International League Hall of Fame in 2010.

3.2. Brooklyn Dodgers

Alston was appointed manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers for the 1954 season. His predecessor, Chuck Dressen, had departed from the Dodgers after the team's leadership declined to offer him a multi-year contract, despite Dressen having won two pennants in three years and nearly a third.

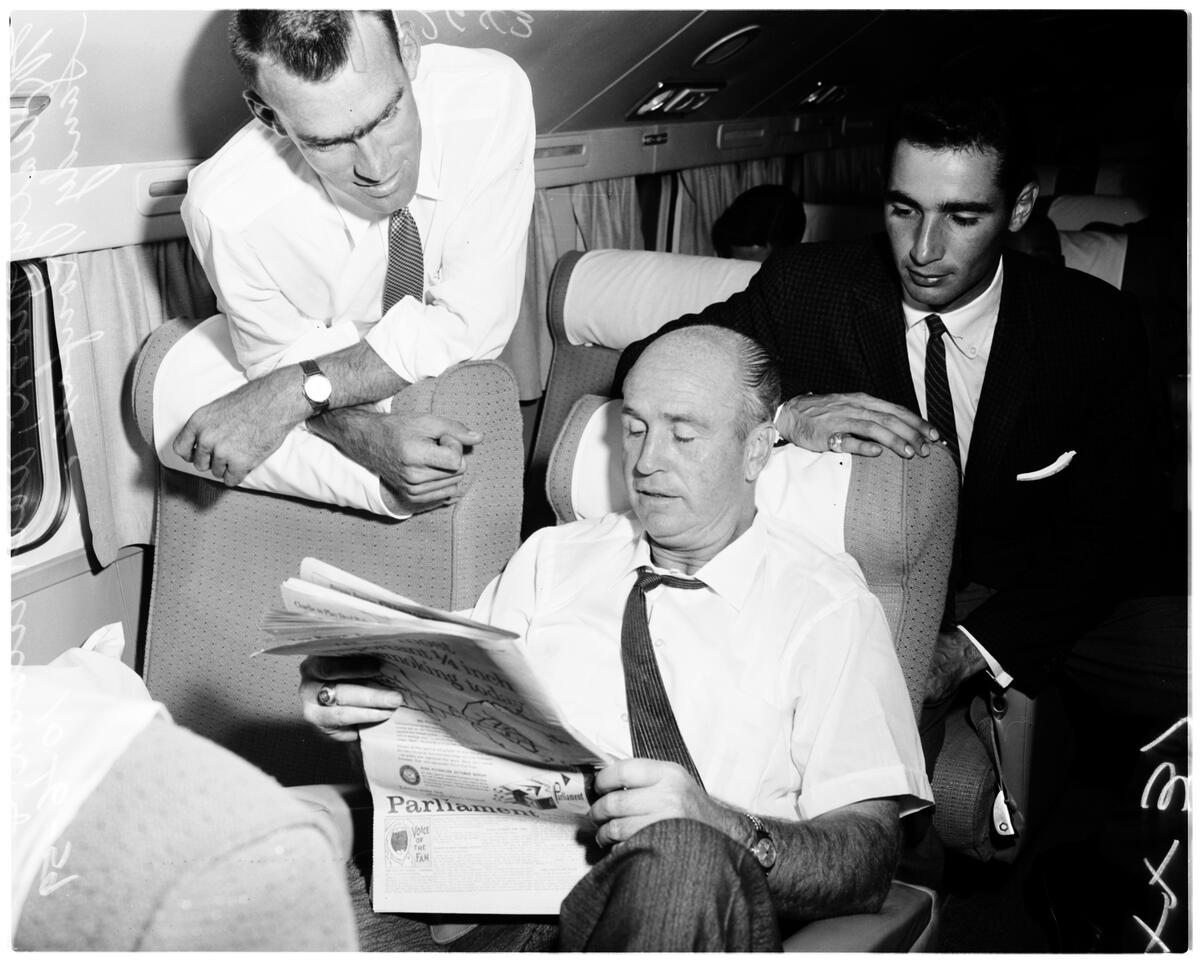

Buzzie Bavasi, a Dodgers executive, was a strong advocate for Alston's hiring in Brooklyn, and bringing Alston to the team is often considered Bavasi's most significant contribution to the Dodgers' history. At the time, Alston was largely unknown at the major league level, prompting the New York Daily News to famously report his hiring with the headline "Walter Who?"

Alston quickly became known for his quiet nature, earning him the nickname "The Quiet Man." His personality sharply contrasted with that of the more outspoken Dressen, which initially posed a challenge for sportswriters who found little to report from him. His seemingly conservative on-field decisions also drew criticism from some players, even those he had managed in the minor leagues. For instance, Don Zimmer stated he learned more from Dressen and believed Dressen knew more about baseball than Alston. According to Jackie Robinson's wife, Robinson himself initially disliked Alston. Alston, however, explained his approach, saying, "I never criticized a player for a mistake on the spot. Whenever I got steamed up about something, I always wanted to sleep on it and face the situation with a clear head." Sportswriter Jim Murray famously remarked that Alston was "the only guy in the game who could look Billy Graham right in the face without blushing and who would order corn on the cob in a Paris restaurant." The 1954 Dodgers finished second in the National League, with both Gil Hodges and Duke Snider hitting at least 40 home runs and recording 130 runs batted in.

The Brooklyn Dodgers started the 1955 season strongly. Despite winning ten consecutive games, an Associated Press article noted Alston's reticence in responding to questions, observing that he did not appear like a manager who had achieved such a winning streak. That year, the Brooklyn Dodgers clinched the National League pennant and their only World Series championship, the sole title won while the club was still based in Brooklyn. They secured the pennant on September 8, earlier than any team in National League history, finishing with a record of 92 wins and 46 losses, 17 games ahead of the second-place Milwaukee Braves with 16 games remaining. In the World Series, Alston started Johnny Podres in two games (the third and seventh); despite a mediocre 9-10 regular season record, Podres won both postseason starts, overcoming arm problems that had plagued him for much of the season.

During this championship season, Sandy Koufax emerged as a promising pitcher for the Dodgers. However, Alston faced criticism from players like Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella for his infrequent use of Koufax in his early career. Despite Koufax pitching a two-hit shutout with 14 strikeouts in his second MLB start, this success did not translate into more opportunities. He appeared in only 12 games that season, mostly in relief, and continued to be used sparingly and inconsistently by Alston over the next few seasons. Years later, Koufax's teammate Don Drysdale suggested to sportswriter Roger Kahn that "latent antisemitism" on Alston's part might have influenced the way Koufax, who was Jewish, was utilized as a young pitcher.

The 1956 team repeated as National League champions, bolstered by the play of Duke Snider, who led the league with 43 home runs and also led in walks. Despite winning the first two games of the World Series, the Dodgers ultimately lost in seven games to the Yankees. The Dodgers then fell to third place with an 84-70 record in 1957, which marked their final season in Brooklyn before the team's historic relocation.

3.3. Los Angeles Dodgers

Alston's managerial career continued to flourish after the Dodgers' move to Los Angeles, where he adapted his strategy to new conditions and led the team to further championships.

3.3.1. Early years in Los Angeles

The team's first season in Los Angeles, 1958, saw them finish in seventh place with a 71-83 record, 21 games out of first. Criticism of Alston began to mount during this period, but he quickly silenced detractors by leading the Dodgers to a World Series championship in 1959. The 1959 team featured six players who hit double-digit home runs, while 22-year-old Don Drysdale led the pitching staff with 17 wins. Some Los Angeles players, including Wally Moon, initially characterized Alston as indecisive in the late 1950s and 1960s. However, Moon later came to describe Alston as a good manager who effectively maximized the performance of his players.

In 1960, Alston, managing the National League All-Star Team, sparked controversy by omitting Milwaukee Braves pitchers Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette from the roster. An Associated Press report suggested this omission might have been a snub directed at Dressen, who was managing in Milwaukee at the time. The 1960 Dodgers finished in fourth place. The following year, the team secured second place after veteran Duke Snider missed two months due to a broken arm. The Dodgers lost their lead in the 1962 National League pennant race, leading to rumors that Alston and coach Leo Durocher might be fired. However, the team retained both for the 1963 season.

The Dodgers swept the 1963 World Series, marking the first time the New York Yankees had lost a World Series in four games. Alston's pitchers were exceptional, with Sandy Koufax striking out 23 batters over two games and earning the World Series MVP Award. Throughout the four-game series, Alston remarkably used only four pitchers: three starters and one reliever. The 1964 team finished with an 80-82 record, their first losing season in several years. Alston used this performance to motivate his team, stating in spring training before the 1965 season that he would not let his team forget the difficulties of the previous year.

The Dodgers returned to the World Series in 1965 against the Minnesota Twins. Alston faced a unique challenge when he could not start his ace pitcher, Koufax, in the opening game on October 6, as Koufax was observing Yom Kippur. Instead, Alston turned to Drysdale, who struggled, surrendering seven runs in just 2⅔ innings. When Alston came to the mound to remove him in the bottom of the third, Drysdale famously quipped, "I bet right now you wish I was Jewish, too." The team recovered from losing the first game and went on to win the World Series in seven games. Koufax made three appearances during the series, recording two shutouts.

Alston's Dodgers teams of the 1960s heavily relied on the strong pitching of Drysdale and Koufax. In 1966, both players held out of spring training, demanding three-year contracts each worth 500.00 K USD, an unprecedented amount in baseball at the time. They eventually signed for lesser amounts. Drysdale struggled that year, but Koufax won 27 games. The Dodgers returned to the World Series but were swept by the Baltimore Orioles. Koufax retired after the season on the advice of doctors regarding his sore arm, and Drysdale retired three years later. Both pitchers had played their entire major league careers under Alston.

3.3.2. Final years as manager

In his final eight years at the helm (1969-1976), Alston guided his teams to at least 85 wins per season, securing six runner-up finishes in the National League West division during that span. The team came very close to a division title in 1971; after falling 11 games out of first place, they performed exceptionally well late in the season, ultimately finishing just one game behind the San Francisco Giants. Beginning in 1973, Alston's team featured a renowned infield of Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell, and Ron Cey. This cohesive group played together for eight years, remaining intact long after Alston's departure.

In 1974, the Dodgers won the National League pennant and faced the two-time defending champion Oakland Athletics in the World Series. Alston notably utilized closer Mike Marshall in a record-setting 106 games that season, and Marshall went on to win the Cy Young Award. Alston garnered some media attention when he considered using Marshall as a starter. Marshall ultimately appeared in all five games of the series, giving up one run in nine innings, but he did not start a game. The Dodgers lost the series four games to one as the Athletics completed their three-peat championship run. The 1975 and 1976 teams won 88 and 92 games respectively, but finished well behind Cincinnati in both seasons.

A rift began to develop among the Dodger players in the mid-1970s. Garvey was heavily promoted by the Dodgers' public relations staff, leading to resentment among some teammates who believed Garvey was overly focused on securing endorsement opportunities. Cey, Lopes, and another unnamed player criticized Garvey in a mid-June 1976 San Bernardino Sun-Telegram article, prompting Alston to call a team meeting. At this meeting, Garvey challenged his teammates, stating, "If anyone has anything to say about me, I want it said to my face, here and now." No one spoke up. Pitcher Tommy John believed it was at this point that Alston began to lose control of the team.

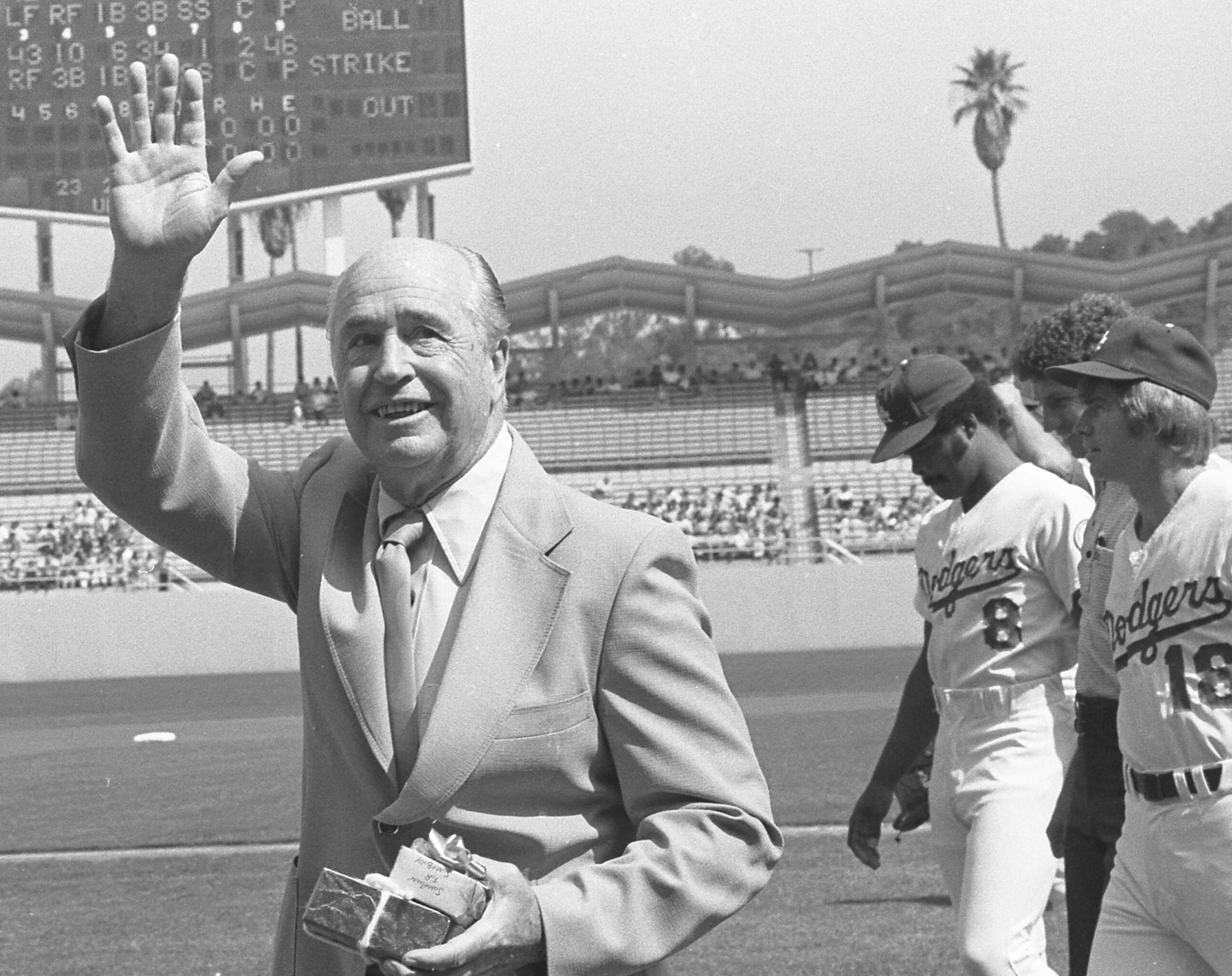

On July 17, 1976, Alston achieved a significant milestone, becoming the fifth manager in Major League Baseball history to win 2,000 games. In September 1976, he announced his retirement at the end of the season. At a press conference, he stated, "I've been in baseball for 41 years and it's been awfully good to me. This has been a pretty big day. I had three birdies playing golf for the first time in my life and now I'm announcing that I'm stepping down as manager. I told Peter O'Malley this afternoon to give somebody else a chance to manage the club." When Tommy Lasorda was chosen as his successor, Alston asked Lasorda to take over as manager for the final four games of the season. Alston retired with 2,063 wins (2,040 in the regular season and 23 in the postseason). He was named National League Manager of the Year six times. He also managed National League All-Star squads a record nine times, winning seven of those games. In an era when multi-year contracts were becoming common, Alston's entire 23-year managerial career consisted of one-year contracts. During this span, he earned seven National League pennants.

Sportswriter Leonard Koppett characterized Alston's role with the Dodgers, noting that while O'Malley was always perceived as "the boss," Alston consistently focused on the on-field management of the team. Koppett suggested that Alston's loyalty and subdued nature contributed significantly to the stability the team enjoyed. O'Malley once remarked that Alston was "non-irritating. Do you realize how important it is to have a manager who doesn't irritate you?"

4. Managerial statistics

| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Tied | Pct. | Games | Won | Lost | Pct. | Notes | |||

| BKN | 1954 | 154 | 92 | 62 | 0 | .597 | 2nd in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| BKN | 1955 | 154 | 98 | 55 | 1 | .641 | 1st in NL | 7 | 4 | 3 | .571 | Won World Series (NYY) |

| BKN | 1956 | 154 | 93 | 61 | 0 | .604 | 1st in NL | 7 | 3 | 4 | .429 | Lost World Series (NYY) |

| BKN | 1957 | 154 | 84 | 70 | 0 | .545 | 3rd in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1958 | 154 | 71 | 83 | 0 | .461 | 7th in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1959 | 156 | 88 | 68 | 0 | .564 | 1st in NL | 6 | 4 | 2 | .667 | Won World Series (CHW) |

| LAD | 1960 | 154 | 82 | 72 | 0 | .532 | 4th in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1961 | 154 | 89 | 65 | 0 | .578 | 2nd in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1962 | 165 | 102 | 63 | 0 | .618 | 2nd in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1963 | 163 | 99 | 63 | 1 | .611 | 1st in NL | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1.000 | Won World Series (NYY) |

| LAD | 1964 | 164 | 80 | 82 | 2 | .494 | 7th in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1965 | 162 | 97 | 65 | 0 | .599 | 1st in NL | 7 | 4 | 3 | .571 | Won World Series (MIN) |

| LAD | 1966 | 162 | 95 | 67 | 1 | .586 | 1st in NL | 4 | 0 | 4 | .000 | Lost World Series (BAL) |

| LAD | 1967 | 162 | 73 | 89 | 0 | .451 | 8th in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1968 | 162 | 76 | 86 | 0 | .469 | 8th in NL | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1969 | 162 | 85 | 77 | 0 | .525 | 4th in NL West | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1970 | 161 | 87 | 74 | 0 | .540 | 2nd in NL West | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1971 | 162 | 89 | 73 | 0 | .549 | 2nd in NL West | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1972 | 155 | 85 | 70 | 0 | .548 | 3rd in NL West | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1973 | 162 | 95 | 66 | 1 | .590 | 2nd in NL West | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1974 | 162 | 102 | 60 | 0 | .630 | 1st in NL West | 9 | 4 | 5 | .444 | Lost World Series (OAK) |

| LAD | 1975 | 162 | 88 | 74 | 0 | .543 | 2nd in NL West | - | - | - | - | |

| LAD | 1976 | 158 | 90 | 68 | 0 | .570 | 2nd in NL West | Resigned* | ||||

| BKN/LAD total | 3658 | 2040 | 1613 | 5 | .558 | 44 | 23 | 21 | .523 | |||

5. Assessment and legacy

Walter Alston's career is widely assessed as one of consistent excellence and quiet leadership, leaving a significant mark on baseball history through his strategic acumen, player development, and subtle but impactful contributions to social progress within the sport.

5.1. Positive assessment

Alston's calm demeanor was a hallmark of his managerial style. He was known for never criticizing a player on the spot, preferring to "sleep on it and face the situation with a clear head" when he felt upset. This composed approach contributed to the stability that the Dodgers enjoyed throughout his long tenure. Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley famously described Alston as "non-irritating," highlighting the importance of a manager who did not create friction.

His strategic success was evident in leading the Dodgers to seven National League pennants and four World Series titles. He was recognized as Manager of the Year six times and holds the record for managing the National League All-Star squads nine times, winning seven of those games. Former Dodgers great Duke Snider acknowledged occasional disagreements with Alston but praised his exceptional ability to utilize the specific strengths of each team he managed. Alston's consistent ability to get "good mileage" out of his players, as noted by Wally Moon, underscored his effectiveness in player development and team optimization.

5.2. Criticism and controversy

Despite his overall success, Alston's managerial style and specific decisions sometimes drew criticism. His quiet nature, which contrasted sharply with his outspoken predecessor Chuck Dressen, initially made it difficult for sportswriters to cover him and led some players to perceive him as overly conservative in his on-field decisions. Don Zimmer felt he learned more from Dressen and believed Dressen had a deeper understanding of baseball. Even Jackie Robinson initially harbored reservations about Alston, according to Robinson's wife.

A notable point of criticism revolved around his sparse and inconsistent use of Sandy Koufax in the pitcher's early career. Despite Koufax's flashes of brilliance, such as a two-hit, 14-strikeout shutout in his second MLB start, Alston did not immediately give him more opportunities, often relegating him to relief roles. This decision was questioned by players like Robinson and Roy Campanella. Koufax's teammate Don Drysdale even suggested that "latent antisemitism" might have played a role in Alston's handling of Koufax, who was Jewish.

In his later years, particularly in the mid-1970s, a rift developed among the Dodger players, exemplified by the tension surrounding Steve Garvey's public promotion. When teammates like Ron Cey and Davey Lopes criticized Garvey, leading to a team meeting, Garvey's direct challenge to his teammates went unanswered. Pitcher Tommy John believed this incident marked the point where Alston began to lose control of the team.

5.3. Influence

Alston's influence extended beyond the diamond, contributing to significant social changes within baseball. His role as player-manager for the Nashua Dodgers in 1946 was pivotal, as it was the first U.S.-based integrated professional baseball team in the twentieth century. He managed Black prospects Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella, demonstrating a pragmatic approach to integration by focusing on their talent and how they could benefit the team. Later, as manager of the St. Paul Saints, he again managed Campanella as the catcher integrated the American Association, navigating media criticism positively.

Alston is also credited with helping to break down barriers for female sports journalists. On October 1, 1974, after the Los Angeles Dodgers clinched the National League West title at the Houston Astrodome, he invited Anita Martini to the post-game press conference in the locker room. This made her the first female journalist allowed access to any Major League locker room, a groundbreaking moment for sports journalism.

6. Posthumous honors

Walter Alston received significant posthumous honors and recognitions that solidified his enduring legacy in baseball history.

6.1. Awards and honors

The Dodgers retired Alston's number 24 the year after he stepped down as manager in 1977, making him only the fourth Dodger to receive that honor at the time. In 1983, he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. However, Alston suffered a heart attack that year and was hospitalized for a month, preventing him from attending his induction ceremony. His grandson traveled to Cooperstown to represent the ailing former manager at the event.

In 1999, Ohio State Route 177 was renamed the Walter "Smokey" Alston Memorial Highway in his honor. He was also inducted into the International League Hall of Fame in 2010, recognizing his successful managerial career in the minor leagues. A memorial dedicated to Alston is located at Milford Township Community Park in his hometown of Darrtown, Ohio.

6.2. Death and mourning

Walter Alston passed away in an Oxford hospital on October 1, 1984, at the age of 72, due to complications from the heart attack he had suffered earlier that year. A funeral home spokesman confirmed that Alston had remained ill since the heart attack. He is interred at Darrtown Cemetery in Darrtown, Ohio.

Upon Alston's death, MLB Commissioner Peter Ueberroth referred to him as one of baseball's greatest managers. Former Dodgers great Duke Snider acknowledged occasional run-ins with Alston but affirmed that Alston excelled at utilizing the specific strengths of each team he managed. Vin Scully, the renowned broadcaster, offered a poignant tribute to Alston, stating:

"I always imagined him to be the type who could ride shotgun on a stage through Indian territory. He was all man and two yards tall. He was very quiet, very controlled. He never made excuses. He gave the players the credit and he took the blame. He was so solid, so American."