1. Overview

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling was a Norwegian military officer and politician who became an infamous Nazi collaborator during World War II. He rose to international prominence through his humanitarian work with Fridtjof Nansen during the Russian famine of 1921 and his diplomatic service in the Soviet Union. After returning to Norway, he served as Minister of Defence from 1931 to 1933. In 1933, Quisling founded the fascist party Nasjonal SamlingNational GatheringNorwegian. Despite his efforts, the party remained peripheral in Norwegian politics, failing to win any seats in the Storting before 1940 and adopting increasingly extreme antisemitic views.

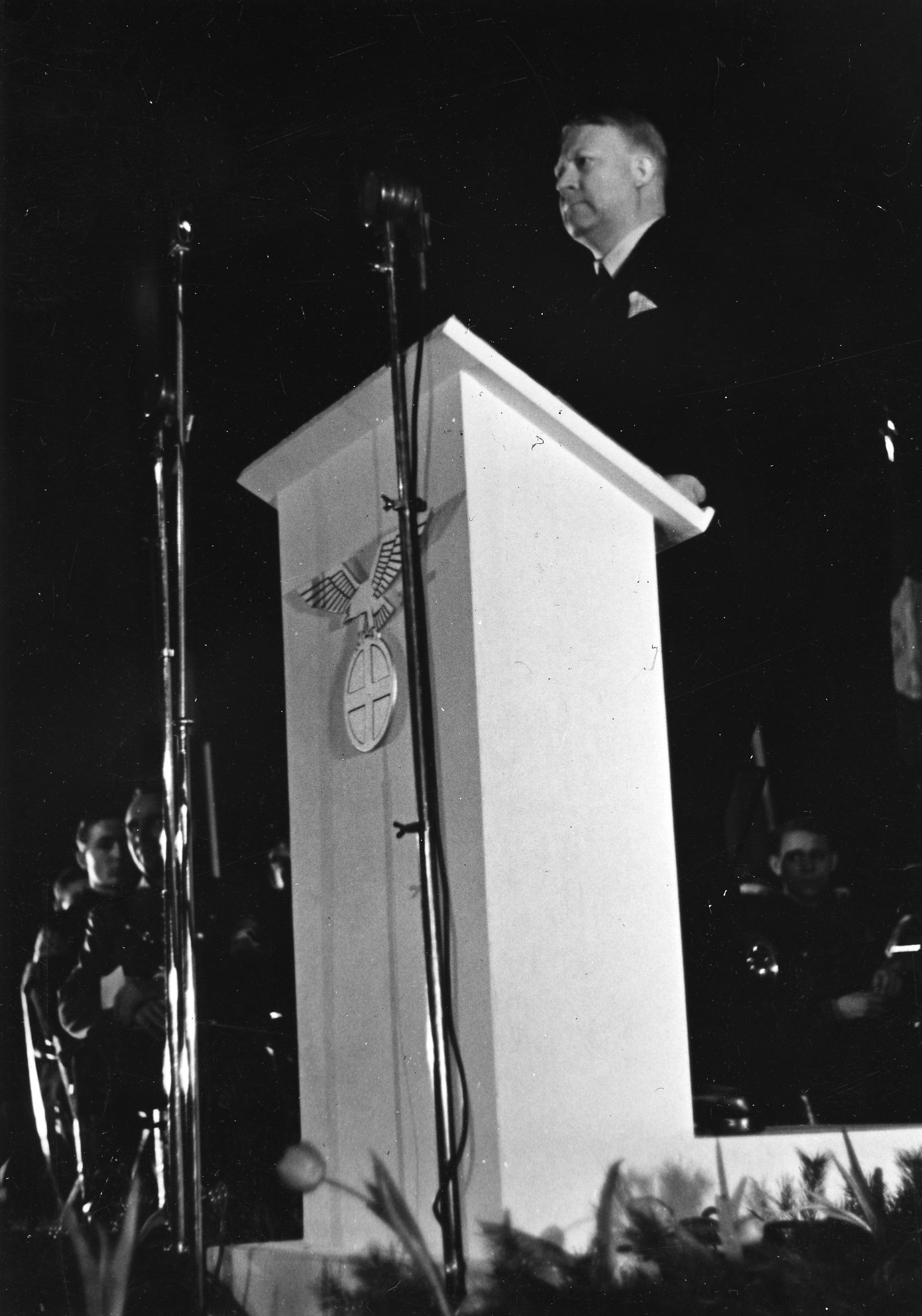

His role became pivotal during the German occupation of Norway. On April 9, 1940, as Germany invaded Norway, Quisling attempted the world's first radio-broadcast coup d'état, though it initially failed due to German hesitation to back him. He was later appointed Minister President of a pro-Nazi puppet government, known as the Quisling regime, which collaborated with the German occupation forces led by Josef Terboven. Under his regime, Norway participated in Germany's war efforts, implementing policies such as censorship, the suppression of the Norwegian resistance movement, and the tragic deportation of Jews to Nazi concentration camps in occupied Poland, marking a devastating impact on democracy and human rights.

Following Germany's surrender in May 1945, Quisling was arrested and tried during the legal purge in Norway after World War II. He was found guilty of numerous charges, including high treason, murder, and embezzlement. Sentenced to death, he was executed by firing squad at Akershus Fortress in Oslo on October 24, 1945. His name, "Quisling," has since become a byword in several languages for "collaborator" or "traitor," reflecting the widespread contempt for his actions.

2. Early Life and Background

Vidkun Quisling's early life, marked by a disciplined upbringing and a successful military career, set the foundation for his later political trajectory. His formative years and initial international engagements provided him with diverse experiences that shaped his worldview.

2.1. Birth and Childhood

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling was born on July 18, 1887, in Fyresdal, a municipality in the Norwegian county of Telemark. He was the son of Jon Lauritz Qvisling (1844-1930), a pastor in the Church of Norway and a noted genealogist. His mother was Anna Caroline Bang (1860-1941), whose father, Jørgen Bang, was a wealthy ship-owner from Grimstad in South Norway. Jon Lauritz Qvisling had lectured in Grimstad in the 1870s, where he met and later married Anna Caroline Bang on May 28, 1886. The couple then moved to Fyresdal, where Vidkun and his two younger brothers and one sister were born.

The family name "Quisling" originated from "Quislinus," a Latinized name created by one of Quisling's ancestors, Lauritz Ibsen Quislin (1634-1703), who had emigrated from the village of Kvislemark near Slagelse, Denmark. During his childhood, the young Quisling was described as "shy and quiet but also loyal and helpful, always friendly, occasionally breaking into a warm smile." Private letters discovered by historians suggest a warm and affectionate relationship among family members. From 1893 to 1900, his father served as a chaplain for the Strømsø borough in Drammen, where Vidkun attended school for the first time. Despite being bullied by other students for his Telemark dialect, he proved to be a successful student. In 1900, the family relocated to Skien after his father was appointed provost of the city.

2.2. Education and Military Career

Academically, Quisling displayed significant talent in the humanities, particularly history, and the natural sciences, specializing in mathematics. In 1905, he enrolled at the Norwegian Military Academy, achieving the highest entrance examination score among 250 applicants that year. He transferred to the Norwegian Military College in 1906, from which he graduated with the highest score recorded since the college's establishment in 1817, an achievement that earned him an audience with King Haakon VII. On November 1, 1911, he joined the army's General Staff.

During First World War, in which Norway maintained neutrality, Quisling expressed disdain for the peace movement, though the high human cost of the conflict tempered some of his views. In March 1918, he was dispatched to Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) as an attaché at the Norwegian legation, leveraging his five years of study on Russia. Despite being dismayed by the poor living conditions, Quisling observed that the Bolsheviks had an "extraordinarily strong hold on Russian society" and admired Leon Trotsky's effective mobilization of the Red Army. He posited that the Russian Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky had contributed to its own downfall by granting too many rights to the Russian people. After the legation was recalled in December 1918, Quisling became the Norwegian military's leading expert on Russian affairs.

2.3. Early Activities and International Engagements

In September 1919, Quisling left Norway to assume a diplomatic and political role as an intelligence officer with the Norwegian delegation in Helsinki. In autumn 1921, he again departed Norway, this time at the request of the renowned explorer and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen, arriving in the Ukrainian capital of Kharkiv in January 1922 to assist with the League of Nations' humanitarian relief efforts during the Russian famine. Quisling documented the severe mismanagement and the staggering death toll, which reached approximately ten thousand per day. His report garnered significant aid and showcased his administrative prowess and determination.

On August 21, 1922, he married the Russian Alexandra Andreevna Voronina. Alexandra later wrote in her memoirs that Quisling declared his love for her, but his letters and investigations by his cousins suggest his primary motive was to help her escape poverty by providing a Norwegian passport and financial security. Quisling and Alexandra returned to Kharkiv in February 1923 to extend the aid efforts, with Nansen deeming Quisling's work "absolutely indispensable." In March 1923, Alexandra became pregnant, and Quisling insisted on an abortion, which caused her significant distress. During this period, Quisling also met Maria Vasiljevna Pasetchnikova, a Ukrainian woman more than ten years his junior. Her diaries from the time indicate a "blossoming love affair" in the summer of 1923, despite his marriage to Alexandra. Maria was reportedly impressed by his fluent Russian, his "Aryan" appearance, and his gracious demeanor.

Quisling later claimed to have married Pasetchnikova in Kharkiv on September 10, 1923, though no legal documentation has been found to confirm this, leading his biographer, Hans Fredrik Dahl, to believe the second marriage was likely unofficial. Nonetheless, they behaved as if married, claimed Alexandra as their foster-daughter, and celebrated their wedding anniversary. Soon after September 1923, the aid mission concluded, and the trio left Ukraine for a planned year in Paris, where Maria wished to see Western Europe, and Quisling sought rest after a winter of stomach pains.

The stay in Paris necessitated a temporary discharge from the army, which Quisling gradually realized would be permanent due to army cutbacks. He became increasingly resentful of the military's treatment, eventually taking a post in the reserves with a reduced captain's salary, and was promoted to major in 1930. In Paris, Quisling dedicated much of his time to studying political theory and developing his philosophical project, which he termed "Universism." On October 2, 1923, he successfully persuaded the Oslo daily newspaper Tidens Tegn to publish his article advocating for diplomatic recognition of the Soviet government. His stay in Paris was cut short, and in late 1923, he began working on Nansen's new repatriation project in the Balkans, arriving in Sofia in November. He spent the next two months traveling with Maria. In January, Maria returned to Paris to care for Alexandra, who became the couple's foster-daughter, and Quisling joined them in February. In the summer of 1924, the trio returned to Norway, where Alexandra then left to live with an aunt in Nice and never returned. Although Quisling promised to support her, his payments were irregular, and he missed many opportunities to visit her in subsequent years.

Back in Norway, and to his later embarrassment, Quisling briefly engaged with the communist Norwegian labor movement. He advocated for a people's militia to defend the country against reactionary attacks and offered to share information the General Staff had on them with movement members, but received no response. Despite this brief association with the far-left, Dahl suggests that following a conservative upbringing, Quisling was at this time "unemployed and dispirited... deeply resentful of the General Staff... [and] in the process of becoming politically more radical." Dahl characterized Quisling's political views at this time as "a fusion of socialism and nationalism," with clear sympathies for the Soviets in Russia.

In June 1925, Nansen again provided Quisling with employment. They embarked on a tour of Armenia, aiming to facilitate the repatriation of Armenians, including Armenian genocide survivors, through projects proposed for League of Nations funding. Despite Quisling's extensive efforts, all the projects were rejected. In May 1926, Quisling found a new position in Moscow with his long-time friend Frederik Prytz, serving as a liaison between Prytz's firm, Onega Wood, and the Soviet authorities who owned half of the company. He held this job until Prytz prepared to close the business in early 1927. Quisling then became the new legation secretary for British diplomatic affairs in Russia, which were being managed by Norway at the time; Maria joined him in late 1928. A major scandal erupted when Quisling and Prytz were accused of using diplomatic channels to smuggle millions of roubles onto the black market. While this claim was widely publicized and used to support a charge of "moral bankruptcy," neither it nor the accusation that Quisling spied for the British has ever been substantiated.

The increasingly hardline political climate in Russia led Quisling to distance himself from Bolshevism. The Soviet government had flatly rejected his Armenian proposals and obstructed Nansen's attempt to assist with the 1928 Ukrainian famine. Quisling took these rebuffs as a personal insult. In 1929, with Britain resuming control of its diplomatic affairs, he departed Russia. For his services to Britain, he was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE), an honor revoked by King George VI in 1940. By this time, Quisling had also received the Romanian Crown Order and the Yugoslav Order of St. Sava for his earlier humanitarian endeavors.

3. Political Career

Quisling's return to Norway marked his decisive shift from military and diplomatic service to a prominent, albeit controversial, figure in national politics. His early ministerial roles and the founding of his own party laid the groundwork for his later wartime actions.

3.1. Minister of Defence

After spending nine of the previous twelve years abroad, and with no practical experience in party politics outside the Norwegian Army, Quisling returned to Norway in December 1929. He brought with him a plan for societal change he called Norsk AktionNorwegian ActionNorwegian, designed as an organization with national, regional, and local units intended to recruit in the style of the Soviet Communist Party. Echoing the French right-wing movement Action Française Action FrançaiseFrench, it advocated for radical constitutional changes, proposing a bicameral Storting with a second chamber composed of Soviet-style elected representatives from the working population. Quisling's focus was more on organizational structure, envisioning all members of Norsk Aktion having designations within a militaristic hierarchy.

He then sold a substantial collection of antiques and works of art he had acquired cheaply in post-revolutionary Russia. His collection included approximately 200 paintings, some purportedly by masters like Rembrandt, Francisco Goya, and Paul Cézanne, insured for nearly 300.00 K NOK. In spring 1930, he reconnected with Prytz, who had also returned to Norway. They participated in regular group meetings with middle-aged officers and businesspeople, which have been described as "the textbook definition of a Fascist initiative group," through which Prytz seemed determined to launch Quisling into politics.

Following Fridtjof Nansen's death on May 13, 1930, Quisling leveraged his friendship with the editor of Tidens Tegn newspaper to publish his analysis of Nansen on the front page. The article, "Politiske tanker ved Fridtjof Nansens død" ("Political Thoughts on the Death of Fridtjof Nansen"), published on May 24, outlined ten points to realize Nansen's vision for Norway, including "strong and just government" and "a greater emphasis on race and heredity." This theme was further developed in his new book, Russland og viRussia and OurselvesNorwegian, serialized in Tidens Tegn during autumn 1930. The openly racist book, which advocated war against Bolshevism, propelled Quisling into the political limelight. Despite his earlier ambivalence, he took a seat on the Oslo board of the formerly Nansen-led Fatherland League. Concurrently, he and Prytz established a new political movement, Nordisk folkereisning i NorgeNordic popular rising in NorwayNorwegian, with a central committee of 31 and Quisling as its fører-a one-man executive committee-though Quisling reportedly had no particular attachment to the term. The movement's first meeting on March 17, 1931, stated its purpose as "eliminat[ing] the imported and depraved communist insurgency."

Quisling left Nordisk folkereisning i Norge in May 1931 to serve as Defence Minister in the Agrarian government of Peder Kolstad, despite not being an Agrarian party member or a friend of Kolstad. His appointment, suggested to Kolstad by Thorvald Aadahl (editor of the Agrarian newspaper Nationen) under Prytz's influence, surprised many in the Parliament of Norway. Quisling's first action in office was to address the aftermath of the Battle of Menstad, a "bitter" labor dispute, by deploying troops. After narrowly avoiding criticism from the left wing over his handling of the dispute and the revelation of his earlier "militia" plans, Quisling focused on the perceived threat from communists. He compiled a list of leaders of the Revolutionäre Gewerkschafts Opposition Revolutionäre Gewerkschafts OppositionGerman (Revolutionary Trade Union Opposition), whom he alleged were agitators at Menstad; several were eventually charged with subversion and violence against the police. Quisling's policies also led to the establishment of a permanent, counter-revolutionary militia called the Leidang. Despite the availability of junior reserve officers due to defense cuts, only seven units were formed by 1934, and funding constraints limited the force to fewer than a thousand men before its eventual dissolution. Sometime between 1930 and 1933, Quisling's first wife, Alexandra, received notice of the annulment of her marriage to him.

In mid-1932, Nordisk folkereisning i Norge confirmed that Quisling, though still in the cabinet, would not become a party member, and stated that its program had no basis in fascism, including the National Socialism model. This did not curb criticism of Quisling, who remained a constant fixture in headlines, though he was also gaining a reputation as a disciplined and efficient administrator. On February 2, 1932, he was attacked in his office by a knife-wielding assailant who threw ground pepper in his face. Some newspapers, instead of focusing on the attack, suggested the assailant was a jealous husband of one of Quisling's cleaners; others, particularly those aligned with the Labour Party, posited the incident was staged. In November 1932, Labour politician Johan Nygaardsvold raised this theory in Parliament, prompting suggestions of slander charges against him, but none were brought. The assailant's identity remains unconfirmed; Quisling later hinted it was an attempt to steal military papers. The "pepper affair" polarized opinions about Quisling, while government fears grew regarding open Soviet elements promoting industrial unrest in Norway.

Following Kolstad's death in March 1932, Quisling retained his Defence Minister post in the second Agrarian government under Jens Hundseid for political reasons, despite their bitter opposition. As under Kolstad, Quisling was involved in many disputes characterizing Hundseid's government. On April 8 of that year, Quisling used an opportunity in Parliament to defend himself over the pepper affair to instead attack the Labour and Communist parties, labeling named members as criminals and "enemies of our fatherland and our people." Overnight, support for Quisling from right-wing elements soared, leading 153 distinguished signatories to call for an investigation into his claims, followed by tens of thousands of Norwegians. Quisling spent the summer delivering speeches to packed political rallies. However, in Parliament, his speech was widely seen as political suicide due to weak evidence and questions about why the information had not been presented earlier if the revolutionary threat was so severe.

3.2. Founding and Development of Nasjonal Samling

Throughout 1932 and into 1933, Prytz's influence over Nordisk folkereisning i Norge diminished, and lawyer Johan Bernhard Hjort assumed a leadership role. Hjort sought to collaborate with Quisling due to his newfound popularity, and together they developed a new program of right-wing policies. These included the proscription of revolutionary parties, particularly those funded by foreign entities like Comintern, the suspension of voting rights for welfare recipients, agricultural debt relief, and an audit of public finances. In 1932, during the Kullmann Affair, Quisling confronted the prime minister for questioning his hardline stance against pacifist agitator Captain Olaf Kullmann. In a memorandum outlining his economic and social reform proposals, distributed to the entire cabinet, Quisling called for the prime minister to resign. As the government neared collapse, Quisling's personal popularity reached new heights; he was hailed as "man of the year," and expectations of electoral success grew.

Despite the new program, some within Quisling's circle still favored a cabinet coup. He later stated that he had even considered using force to overthrow the government. However, in late February, it was the Liberal Party that brought the government down. With the assistance of Hjort and Prytz, Nordisk folkereisning i Norge quickly transformed into a political party, Nasjonal SamlingNational GatheringNorwegian, or NS, prepared to contest the upcoming October parliamentary election. Quisling was somewhat disappointed, having preferred to lead a national movement rather than just one of seven political parties. Nasjonal Samling soon announced it would support candidates from other parties if they aligned with its core objective: "establishing a strong and stable national government independent of ordinary party politics." Though not an immediate success in the already crowded political landscape, the party gradually gained support. With its Nazi-inspired belief in the central authority of a strong Führer and powerful propaganda, it attracted many among the Oslo upper classes, giving the impression that it had significant financial backing.

Increased support also emerged when the Bygdefolkets Krisehjelp, the Norwegian Farmers' Aid Association, sought financial assistance from Nasjonal Samling, which in turn gained political influence and access to an existing network of well-trained party officers. However, Quisling's party never succeeded in forming a grand anti-socialist coalition, partly due to competition from the Conservative Party for right-wing votes. Although Quisling remained an unskillful orator, his reputation for scandal ensured that the electorate was aware of Nasjonal Samling's existence. As a result, the party achieved only moderate success in the October election, securing 27,850 votes-approximately two percent of the national vote, and about three and a half percent in constituencies where it fielded candidates. This made it the fifth largest party in Norway, outpolling the Communists but trailing the Conservative, Labour, Liberal, and Agrarian parties, and failing to secure a single seat in Parliament.

Following the underwhelming election results, Quisling's approach to negotiation and compromise hardened. A final attempt to form a right-wing coalition in March 1934 failed, and from late 1933, Quisling's Nasjonal Samling began to develop its own distinct form of national socialism. Without a leader in Parliament, however, the party struggled to introduce the necessary constitutional reform bill to achieve its ambitions. When Quisling attempted to introduce the bill directly, it was swiftly rejected, and the party entered a period of decline. In summer 1935, headlines reported Quisling stating that "heads [would] roll" once he gained power. This threat severely damaged the party's image, leading to the resignation of several high-ranking members over the following months, including Kai Fjell and Quisling's brother Jørgen.

Quisling began familiarizing himself with the international fascist movement, attending the 1934 Montreux Fascist conference in December. For his party, the association with Italian fascism came at an inopportune moment, shortly after headlines concerning illegal Italian incursions into Abyssinia. Upon his return from Montreux, he met Nazi ideologue and foreign policy theorist Alfred Rosenberg. Although Quisling preferred to view his own policies as a synthesis of Italian fascism and German Nazism, by the time of the 1936 elections, he had partly become the "Norwegian Hitler" his opponents had long accused him of being. This transformation was partly due to his increasingly hardened antisemitic stance, where he associated Judaism with Marxism, liberalism, and anything else he found objectionable, and partly due to Nasjonal Samling's growing resemblance to the German Nazi Party. Despite receiving an unexpected boost when the Norwegian government acceded to Soviet demands to arrest Leon Trotsky, the party's election campaign never gained momentum. Although Quisling genuinely believed he had the support of around 100,000 voters and declared to his party that they would win a minimum of ten seats, Nasjonal Samling only managed to poll 26,577 votes, fewer than in 1933 when they had fielded candidates in only half the districts. Under this pressure, the party split into two, with Hjort leading the breakaway group; although fewer than fifty members left immediately, many more gradually departed during 1937.

Dwindling party membership created numerous problems for Quisling, especially financial ones. For years, he had faced financial difficulties and relied on his inheritance. An increasing number of his paintings, which he attempted to sell, were found to be copies. Vidkun and his brother Arne sold one Frans Hals painting for just 4.00 K USD, believing it to be a copy, only to later discover it was an original valued at 100.00 K USD. In the challenging economic climate of the Great Depression, even originals did not fetch as much as Quisling had hoped. His disillusionment with Norwegian society deepened with news of the planned constitutional reform of 1938, which would extend the parliamentary term from three to four years with immediate effect, a move Quisling bitterly opposed.

4. World War II and Collaboration

Quisling's actions during World War II defined his legacy as a notorious collaborator. His unwavering support for Nazi Germany, culminating in his leadership of a puppet regime, deeply impacted Norway's sovereignty and its citizens' human rights.

4.1. Pre-Invasion Activities and Contacts with Germany

In 1939, Quisling shifted his focus to Norway's preparations for the anticipated European war, advocating for a drastic increase in the country's defense spending to secure its neutrality. Concurrently, he delivered lectures titled "The Jewish problem in Norway" and publicly supported Adolf Hitler as the looming conflict intensified. Despite condemning Kristallnacht, Quisling sent Hitler a greeting on his fiftieth birthday, expressing thanks for "saving Europe from Bolshevism and Jewish domination." He also contended that if an Anglo-Russian alliance rendered neutrality impossible, Norway would "have to go with Germany." Invited to Germany in summer 1939, he toured several German and Danish cities. He received a particularly warm reception in Germany, which promised funds to bolster Nasjonal Samling's standing in Norway and thereby spread pro-Nazi sentiment. When war erupted on September 1, 1939, Quisling felt vindicated by both the event and the immediate superiority demonstrated by the German army. He remained outwardly confident that, despite its small size, his party would soon become the center of political attention.

For the next nine months, Quisling continued to lead a party that remained largely peripheral to Norwegian politics. Nevertheless, he was active, working with Prytz in October 1939 on an ultimately unsuccessful plan for peace between Britain, France, and Germany, envisioning their eventual participation in a new economic union. Quisling also pondered how Germany ought to launch an offensive against its ally, the Soviet Union, and on December 9, traveled to Germany to present his multi-faceted plans. After impressing German officials, he secured an audience with Hitler, scheduled for December 14. His contacts firmly advised him that the most beneficial course of action would be to request Hitler's assistance for a pro-German coup in Norway, which would allow Germany to use Norway as a naval base. Subsequently, Norway would maintain official neutrality for as long as possible, ultimately falling under German rather than British control. It remains unclear how much Quisling truly grasped the strategic implications of such a move; he instead relied on his future Minister of Domestic Affairs, Albert Viljam Hagelin, who was fluent in German, to present the relevant arguments to German officials in Berlin during pre-meeting discussions, despite Hagelin's tendency for damaging exaggeration. Quisling and his German contacts almost certainly departed with differing understandings of whether they had agreed upon the necessity of a German invasion.

On December 14, 1939, Quisling met Hitler. The German leader promised to respond to any British invasion of Norway, potentially pre-emptively, with a German counter-invasion, but found Quisling's plans for both a Norwegian coup and an Anglo-German peace overly optimistic. Nevertheless, Quisling was assured of continued funds to bolster Nasjonal Samling. Immediately after this meeting, Hitler ordered his staff to begin preparations for an invasion of Norway. The two men met again four days later, after which Quisling drafted a memorandum explicitly stating to Hitler that he did not consider himself a National Socialist. As German machinations continued, Quisling was intentionally kept uninformed. He was also incapacitated by a severe bout of illness, likely nephritis affecting both kidneys, for which he refused hospitalization. Though he returned to work on March 13, 1940, he remained ill for several weeks. Meanwhile, the Altmark incident complicated Norway's efforts to maintain its neutrality. Hitler himself remained undecided on whether an occupation of Norway would require an invitation from the Norwegian government. Finally, Quisling received his summons on March 31, reluctantly traveling to Copenhagen to meet with Nazi intelligence officers who requested information on Norwegian defenses and protocols. He returned to Norway on April 6, and on April 8, the British Operation Wilfred commenced, drawing Norway into the war. With Allied forces present in Norway, Quisling anticipated a characteristically swift German response.

4.2. German Invasion and Attempted Coup

In the early hours of April 9, 1940, Germany launched "Operation Weserübung" (Operation Weser Exercise), invading Norway by air and sea with the intention of capturing King Haakon VII and the government of Prime Minister Johan Nygaardsvold. However, alerted to the possibility of invasion, Conservative President of the Parliament C. J. Hambro arranged for their evacuation to Hamar in the east of the country. The German cruiser Blücher, which transported most of the personnel intended to take over Norway's administration, was sunk by cannon fire and torpedoes from Oscarsborg Fortress in the Oslofjord. This mix-up was partly attributed to Quisling's earlier statement to the Germans that he "did not believe" Norwegian sea defenses would open fire without prior orders. The Germans had expected the government to surrender and a replacement to be ready; neither occurred, though the invasion continued. After hours of discussion, Quisling and his German counterparts decided an immediate coup was necessary, despite it not being the preferred option of either Germany's ambassador Curt Bräuer or the German Foreign Ministry.

In the afternoon, German liaison officer Hans-Wilhelm Scheidt informed Quisling that if he formed a government, it would have Hitler's personal approval. Quisling drafted a list of ministers and, although the legitimate government had only relocated some 93 mile (150 km) to Elverum, he falsely accused it of having "fled." Meanwhile, the Germans occupied Oslo, and at 17:30, Norwegian radio (NRK) ceased broadcasting at the request of the occupying forces. With German support, at approximately 19:30, Quisling entered the NRK studios in Oslo and proclaimed the formation of a new government with himself as prime minister. He also revoked an earlier order to mobilize against the German invasion. He still lacked legitimacy; two of his orders-the first to his friend Colonel Hans Sommerfeldt Hiorth, the commanding officer of the army regiment at Elverum, to arrest the government, and the second to Kristian Welhaven, Oslo's chief of police-were both ignored. At 22:00, Quisling resumed broadcasting, repeating his earlier message and reading out a list of new ministers. Hitler lent his support as promised, recognizing the new Norwegian government under Quisling within 24 hours. Norwegian batteries were still firing on the German invasion force, and at 03:00 on April 10, Quisling acceded to a German request to halt the resistance of the Bolærne fortress. As a result of actions such as these, it was claimed at the time that Quisling's seizure of power in a puppet government had been part of the German plan all along.

Quisling now reached the peak of his political power. On April 10, Bräuer traveled to Elverum, where the legitimate Nygaardsvold government was located. Under Hitler's orders, Bräuer demanded that King Haakon appoint Quisling head of a new government, thereby ensuring a peaceful transition of power and providing legal sanction for the occupation. King Haakon rejected this demand. In a meeting with his cabinet, the King went further, stating he could not appoint Quisling prime minister because neither the people nor the Storting had confidence in him, and he would sooner abdicate than appoint any government led by Quisling. Hearing this, the government unanimously voted to support the King's stance, formally advising him against appointing any government headed by Quisling, and urging the people to continue their resistance. With his popular support gone, Quisling ceased to be useful to Hitler. Germany retracted its support for his rival government, preferring instead to establish its own independent governing commission. In this manner, Quisling was maneuvered out of power by Bräuer and a coalition of his former allies, including Hjort, who now viewed him as a liability. Even his political allies, including Prytz, abandoned him. In return, Hitler wrote to Quisling, thanking him for his efforts and guaranteeing him some form of position in the new government. The transfer of power on these terms was enacted on April 15, with Hitler still confident the Administrative Council would receive the King's backing. Quisling's domestic and international reputation plummeted, casting him as both a traitor and a failure.

4.3. Establishment of the Quisling Regime

Once the King declared the German commission unlawful, it became clear that he would never be swayed. An impatient Hitler appointed a German, Josef Terboven, as the new Norwegian Reichskommissar ReichskommissarGerman, or governor-general, on April 24, reporting directly to him. Despite Hitler's earlier assurances to Quisling, Terboven sought to ensure there would be no place in the government for the Nasjonal Samling or its leader, with whom he had a poor relationship. Terboven eventually accepted a certain Nasjonal Samling presence in the government during June but remained unconvinced about Quisling. Consequently, on June 25, Terboven compelled Quisling to step down as leader of the Nasjonal Samling and take a temporary leave of absence in Germany. Quisling remained there until August 20, while Alfred Rosenberg and Admiral Erich Raeder, whom he had met on his earlier visit to Berlin, negotiated on his behalf. Ultimately, Quisling returned "in triumph," having persuaded Hitler in a meeting on August 16. The Reichskommissar ReichskommissarGerman was then forced to accommodate Quisling as leader of the government, allow him to rebuild the Nasjonal Samling, and incorporate more of his followers into the cabinet. Terboven complied, announcing in a radio broadcast to the Norwegian people that the Nasjonal Samling would be the only political party allowed.

By the end of 1940, the monarchy had been suspended, although the Parliament of Norway and a cabinet-like body remained. The Nasjonal Samling, as the only pro-German party, was to be cultivated, but Terboven's Reichskommissariat ReichskommissariatGerman retained ultimate power. Quisling served as acting prime minister, and ten of the thirteen "cabinet" ministers were drawn from his party. He embarked on a program aimed at eradicating "the destructive principles of the French Revolution", including pluralism and parliamentary rule. This extended to local politics, where mayors who switched allegiance to the Nasjonal Samling were granted significantly expanded powers. Investments were made in heavily censored cultural programs, though the press theoretically remained free. To bolster the survival chances of the Nordic genotype, contraception was severely restricted. Quisling's party experienced a surge in membership to just over 30,000, but despite his optimism, it never surpassed the 40,000 mark.

4.4. Policies and Governance Under Occupation

On December 5, 1940, Quisling flew to Berlin to negotiate Norway's future independence. By the time he returned on December 13, he had agreed to raise volunteers to fight with the German Schutzstaffel SchutzstaffelGerman (SS). In January, SS head Heinrich Himmler traveled to Norway to oversee preparations. Quisling genuinely believed that if Norway supported Nazi Germany on the battlefield, there would be no reason for Germany to annex it. To this end, he opposed plans to install a German SS brigade in Norway loyal only to Hitler. In the process, he also hardened his stance towards the United Kingdom, which harbored the exiled king, no longer viewing it as a Nordic ally. Finally, Quisling aligned Norwegian policy on Jews with that of Germany, delivering a speech in Frankfurt on March 26, 1941, in which he argued for compulsory exile but cautioned against extermination. He stated: "And since the Jewish question cannot be solved by simply exterminating the Jews or sterilizing them, secondly their parasitic existence must be prevented by giving them, like the other peoples of the earth, their own land. However, their former land, Palestine, has been the land of the Arabs for centuries. There is therefore no better and milder way to solve the Jewish problem than to get them another so-called promised land and to send them all there together, so as to, if possible, bring the eternal Jew and his divided soul to rest."

In May, Quisling was deeply affected by the death of his mother, Anna, as they shared a particularly close bond. Concurrently, the political crisis regarding Norwegian independence intensified, with Quisling threatening Terboven with his resignation over financial matters. Ultimately, the Reichskommissar agreed to a compromise on finance, but Quisling had to concede on the SS issue: a brigade was formed, but as a branch of the Nasjonal Samling.

Meanwhile, the government's stance hardened, leading to the arrest of Communist Party leaders and intimidation of trade unionists. On September 10, 1941, Viggo Hansteen and Rolf Wickstrøm were executed, and many more were imprisoned following the milk strike in Oslo. Hansteen's execution was later viewed as a watershed moment, demarcating the occupation into its more innocent and more deadly phases. The same year, Statspolitiet StatspolitietNorwegian ("the State Police"), which had been abolished in 1937, was reestablished to assist the Gestapo in Norway, and radio sets were confiscated nationwide. Although these were all Terboven's decisions, Quisling supported them and proceeded to denounce the government-in-exile as "traitors." As a consequence of this tougher stance, an informal "ice front" emerged, leading to Nasjonal Samling supporters being ostracized from society. Quisling remained convinced that this was anti-German sentiment that would dissipate once Berlin transferred power to Nasjonal Samling. However, the only concessions he secured in 1941 were the promotion of ministry heads to official government ministers and independence for the party secretariat.

In January 1942, Terboven announced that the German administration would be wound down. Soon after, he informed Quisling that Hitler had approved the transfer of power, scheduled for January 30. Quisling remained doubtful, as Germany and Norway were engaged in complex peace negotiations that could not be completed until peace was achieved on the Eastern Front, while Terboven insisted that the Reichskommissariat ReichskommissariatGerman would remain in power until such peace materialized. Nevertheless, Quisling could be reasonably confident that his position within the party and with Berlin was unassailable, even if he was unpopular within Norway, a fact of which he was well aware.

After a brief postponement, an announcement was made on February 1, 1942, detailing how the cabinet had elected Quisling to the post of minister president of the national government. The appointment was accompanied by a banquet, rallying, and other celebrations by Nasjonal Samling members. In his inaugural speech, Quisling committed the government to closer ties with Germany. The only change to the Constitution was the reinstatement of the ban on Jewish entry into Norway, which had been abolished in 1851.

His new position provided Quisling with a security of tenure he had not previously enjoyed, although the Reichskommissariat ReichskommissariatGerman remained outside his direct control. A month later, in February 1942, Quisling undertook his first state visit to Berlin. It was a productive trip, during which all key issues concerning Norwegian independence were discussed-but Joseph Goebbels in particular remained unconvinced of Quisling's capabilities, noting that it was "unlikely" he would "...ever make a great statesman."

Back in Norway, Quisling was less concerned about Nasjonal Samling's membership numbers and even advocated for purging the membership list, including removing drunkards. On March 12, 1942, Norway officially became a one-party state. In time, criticism of and resistance to the party were criminalized, though Quisling expressed regret for having to take this step, hoping that every Norwegian would freely come to accept his government.

This optimism was short-lived. During the summer of 1942, Quisling lost any remaining ability to sway public opinion by attempting to compel children to join the Nasjonal Samlings Ungdomsfylking, a youth organization modeled on the Hitler Youth. This initiative prompted a mass resignation of teachers from their professional body and churchmen from their posts, alongside widespread civil unrest. His attempted indictment of Bishop Eivind Berggrav proved similarly controversial, even among his German allies. Quisling then toughened his stance, informing Norwegians that the new regime would be imposed upon them "whether they like it or not." On May 1, 1942, the German High Command noted that "organized resistance to Quisling has started," leading to a stall in Norway's peace talks with Germany. On August 11, 1942, Hitler postponed any further peace negotiations until the war's end. Quisling was admonished and learned that Norway would not achieve the independence he so desperately desired. As an added insult, for the first time, he was forbidden to write letters directly to Hitler.

Quisling had earlier advocated for a corporate alternative to the Storting, which he called a RikstingNorwegian. It was envisioned to comprise two chambers: the NæringstingNorwegian (Economic Chamber) and the KulturtingNorwegian (Cultural Chamber). However, leading up to Nasjonal Samling's eighth and final national convention on September 25, 1942, and growing increasingly distrustful of professional bodies, he changed his mind. The Riksting became an advisory body, while the FørertingNorwegian, or Leader Council, and parliamentary chambers were now designated as independent bodies subordinate to their respective ministries; only the Cultural Chamber actually materialized, as the Economic Chamber was postponed due to unrest within the professional bodies it was meant to represent.

After the convention, support for Nasjonal Samling, and Quisling personally, waned significantly. Increased factionalism and personal losses, including the accidental death of fellow politician Gulbrand Lunde, were compounded by heavy-handed German tactics, such as the shooting of ten well-known residents of Trøndelag and its environs in October 1942. Additionally, the lex Eilifsen ex-post facto law of August 1943, which resulted in the regime's first death sentence, was widely seen as a blatant violation of the Constitution and a grim indication of Norway's increasing involvement in the Final Solution. This further eroded party morale, undoing any gains from the convention.

With the abetment of the government and Quisling's personal involvement, Jews were registered as part of a German initiative in January 1942. On October 26, 1942, German forces, assisted by the Norwegian police, arrested 300 registered male Jews in Norway and dispatched them to concentration camps, primarily Berg concentration camp, which was manned by the Hirden HirdenNorwegian, the paramilitary wing of Nasjonal Samling. Most controversially, the Jews' property was confiscated by the state through a law enacted on October 26, 1942. While this was primarily a German initiative, and Quisling himself was initially unaware of the deportations, government assistance was provided. Quisling led the Norwegian public to believe that the first deportation of Jewish people, to camps in Nazi-German occupied Poland, was his idea. A further 250 Jews were deported in February 1943. It remains unclear what the party's official position was on the eventual fate of the 759 Norwegian deportees. There is evidence to suggest that Quisling honestly believed the official German line throughout 1943 and 1944 that they were awaiting repatriation to a new Jewish homeland in Madagascar, despite their actual destination being the extermination camp at Auschwitz.

At the same time, Quisling believed that the only way to regain Hitler's respect was to raise volunteers for the faltering German war effort. He committed Norway wholeheartedly to German plans for total war. For him, especially after the German defeat at Battle of Stalingrad in February 1943, Norway now had a role to play in maintaining the strength of the German empire. In April 1943, Quisling delivered a scathing speech criticizing Germany's refusal to outline its plans for post-war Europe. When he presented this directly to Hitler, the Nazi leader remained unmoved despite Norway's contributions to the war effort. Quisling felt betrayed by this postponement of Norwegian freedom, an attitude that only softened when Hitler eventually committed to a free post-war Norway in September 1943.

Quisling grew weary during the final years of the war. He passed 231 laws in 1942, 166 in 1943, and 139 in 1944. Social policy remained one area that received significant attention. By autumn 1944, Quisling and Mussert in the Netherlands could be satisfied that they had at least survived. In 1944, the weight problems Quisling had experienced over the preceding two years also eased.

Despite the increasingly dire military outlook in 1943 and 1944, Nasjonal Samling's position at the head of the government, albeit with its ambiguous relationship to the Reichskommissariat ReichskommissariatGerman, remained unassailable. Nevertheless, the Germans exerted increasing control over law and order in Norway. Following the deportation of the Jews, Germany deported Norwegian officers and finally attempted to deport students from the University of Oslo. Even Hitler was incensed by the scale of the arrests. Quisling became embroiled in a similar debacle in early 1944 when he forced compulsory military service on elements of the Hirden HirdenNorwegian, causing a number of members to resign to avoid being drafted.

On January 20, 1945, Quisling made what would be his final trip to visit Hitler. He pledged Norwegian support in the final phase of the war if Germany agreed to a peace deal that would remove German intervention from Norway's affairs. This proposal stemmed from a fear that as German forces retreated southward through Norway, the occupation government would struggle to maintain control in northern Norway. To the horror of the Quisling regime, the Nazis instead opted for a scorched earth policy in northern Norway, going so far as to shoot Norwegian civilians who refused to evacuate the region. This period was also marked by increasing civilian casualties from Allied air raids and mounting resistance to the government within occupied Norway. The meeting with the German leader proved unsuccessful, and upon being asked to sign the execution order for thousands of Norwegian "saboteurs," Quisling refused. This act of defiance so enraged Terboven, who was acting on Hitler's orders, that he stormed out of the negotiations. Recounting the events of the trip to a friend, Quisling broke down in tears, convinced that the Nazi refusal to sign a peace agreement would seal his reputation as a traitor.

Quisling spent the last months of the war attempting to prevent Norwegian casualties in the impending showdown between German and Allied forces in Norway. His regime worked for the safe repatriation of Norwegians held in German prisoner-of-war camps. Privately, Quisling had long accepted that National Socialism would be defeated. Hitler's suicide on April 30, 1945, left him free to publicly pursue his chosen end-game: a naive offer of a transition to a power-sharing government with the government-in-exile.

On May 7, Quisling ordered the police not to offer armed resistance to the Allied advance except in self-defense or against overt members of the Norwegian resistance movement. The same day, Germany announced its unconditional surrender, rendering Quisling's position untenable. A realist, Quisling met with military leaders of the resistance on May 8 to discuss the terms of his arrest. He declared that while he did not wish to be treated as a common criminal, he also did not seek preferential treatment compared to his Nasjonal Samling colleagues. He argued that he could have kept his forces fighting until the end but had chosen not to, to avoid turning "Norway into a battlefield." Instead, he sought to ensure a peaceful transition. In return, the resistance offered full trials for all accused Nasjonal Samling members after the war, and its leadership agreed that he could be incarcerated in a house rather than a prison complex.

5. Arrest and Trial

The immediate aftermath of World War II saw Quisling's swift apprehension and a high-profile trial that cemented his image as a traitor in Norwegian history.

5.1. Arrest

The civil leadership of the resistance, represented by lawyer Sven Arntzen, demanded that Quisling be treated like any other murder suspect. Consequently, on May 9, 1945, Quisling and his ministers surrendered to the police. Quisling was transferred to Cell 12 in Møllergata 19, the main police station in Oslo. The cell was sparsely furnished, equipped with a tiny table, a basin, and a hole in the wall for a toilet bucket. After ten weeks under constant surveillance to prevent suicide attempts while in police custody, he was transferred to Akershus Fortress to await trial as part of the extensive legal purge targeting collaborators. He soon began working on his case with Henrik Bergh, a lawyer with a good track record but who was, at least initially, largely unsympathetic to Quisling's predicament. Bergh, however, came to believe Quisling's testimony that he had consistently tried to act in Norway's best interests and decided to use this as the foundation for the defense.

5.2. Trial Proceedings

Initially, Quisling's charges revolved around his attempted coup, including his revocation of the mobilization order, his tenure as Nasjonal Samling leader, and his actions as minister president, such as assisting the enemy and illegally attempting to alter the constitution. Additionally, he was accused of Gunnar Eilifsen's murder. While not contesting the key facts, he denied all charges, arguing that he had consistently worked for a free and prosperous Norway, and he submitted a sixty-page response to the accusations. On July 11, 1945, a further indictment was issued, adding a raft of new charges, including more murders, theft, embezzlement, and, most critically for Quisling, the charge of conspiring with Hitler regarding the invasion and occupation of Norway.

The trial formally opened on August 20, 1945. Quisling's defense strategy aimed to downplay his unity with Germany and emphasize his struggle for total independence for Norway-a position that directly contradicted the recollections of many Norwegians. As biographer Hans Fredrik Dahl observed, Quisling had to tread a "fine line between truth and falsehood," emerging from the process as "an elusive and often pitiful figure." He misrepresented the truth on several occasions, and even the truthful majority of his statements garnered him few advocates in the country, where he remained almost universally despised. In the later stages of the trial, Quisling's health deteriorated, largely due to the numerous medical tests he underwent, and his defense consequently faltered. The prosecution's final speech placed the responsibility for the implementation of the Final Solution in Norway squarely on Quisling, drawing upon the testimonies of German officials. Prosecutor Annæus Schjødt called for the death penalty, citing laws introduced by the government-in-exile in October 1941 and January 1942.

6. Execution

The legal proceedings against Quisling culminated in his conviction and execution, a definitive end to his life that marked a significant moment in Norway's post-war reckoning.

6.1. Death Sentence and Execution

Speeches by both his lawyer, Henrik Bergh, and Quisling himself proved insufficient to alter the outcome of the trial. When the verdict was announced on September 10, 1945, Quisling was convicted on nearly all charges, with only a handful of minor counts being dismissed, and was sentenced to death. An appeal to the Supreme Court of Norway in October was rejected. The entire court process was widely praised, with author Maynard Cohen describing it as "a model of fairness."

After providing testimony in several other trials involving members of Nasjonal Samling, Quisling was executed by firing squad at Akershus Fortress at 02:40 on October 24, 1945. His last words before being shot were, "I'm convicted unfairly and I die innocent." Following his death, his body was cremated, and his ashes were interred in his birthplace, Fyresdal.

7. Ideology and Philosophy

Quisling's intellectual pursuits and political convictions formed a complex, often contradictory, ideological framework that profoundly shaped his actions and relationship with Nazism.

7.1. Universism

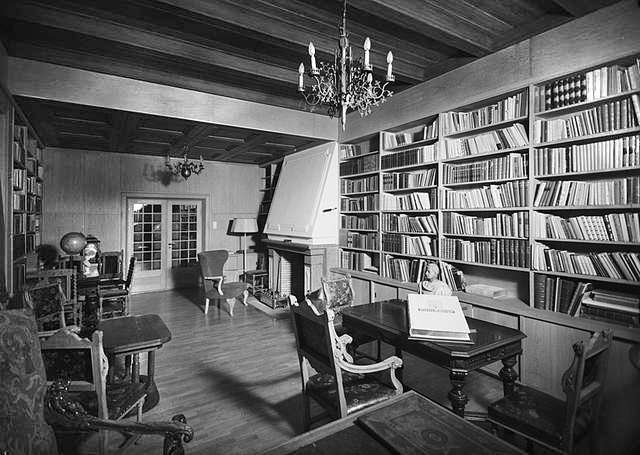

Quisling held a deep interest in science, Eastern religions, and metaphysics, which led him to build a personal library containing works by eminent philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza, Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and Arthur Schopenhauer. He kept abreast of developments in quantum physics but did not engage with more contemporary philosophical ideas. He integrated philosophy and science into a comprehensive worldview he termed "Universism," or "Universalism," conceiving it as a unified explanation of everything. His original writings on this subject reportedly spanned some two thousand pages. The term "Universism" itself was borrowed from a textbook by Jan Jakob Maria de Groot on Chinese philosophy, which posited that Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism were all part of a single world religion De Groot called Universism. Quisling articulated that his philosophy "... followed from the universal theory of relativity, of which the specific and general theories of relativity are special instances."

His self-proclaimed magnum opus on Universism was structured into four parts: an introduction, a description of humanity's apparent progression from individual to increasingly complex consciousnesses, a section on his tenets of morality and law, and a final section covering science, art, politics, history, race, and religion. The concluding part was to be titled The World's Organic Classification and Organisation, but the entire work remained unfinished. Generally, Quisling worked on it infrequently during his political career. Biographer Hans Fredrik Dahl considered this "fortunate," suggesting that Quisling would "never have won recognition" as a philosopher.

During his trial, and particularly after being sentenced, Quisling re-engaged with Universism. He interpreted the events of the war as part of a divine progression towards the establishment of God's kingdom on Earth, using these terms to justify his actions. In the first week of October, he penned a fifty-page document titled Universistic Aphorisms, which represented "...an almost ecstatic revelation of truth and the light to come, which bore the mark of nothing less than a prophet." This document was also notable for its critique of the materialism inherent in Nazism. Concurrently, he worked on a sermon, Eternal Justice, which reiterated his core beliefs, including reincarnation.

7.2. Political Beliefs and Relationship with Nazism

Quisling's political ideology was strongly nationalist and anti-communist. His interpretation and adoption of Fascism and Nazism became evident in his collaborative relationship with the German Nazi Party. He rejected the concept of German racial supremacy, instead asserting that the Norwegian race was the progenitor of Northern Europe, a belief he indulged by meticulously tracing his own family tree in his spare time. His political beliefs manifested in his advocacy for a strong, centralized government and his fervent opposition to liberal democratic principles, which he viewed as destructive. While he claimed not to be a National Socialist himself, his party's structure, rhetoric, and policies increasingly mirrored those of the German Nazi Party, particularly his hardening stance on antisemitism and his alignment with German wartime objectives.

8. Legacy and Assessment

Vidkun Quisling's life concluded with his execution, but his legacy persists, primarily through the ignominious term derived from his name. His personal character, often debated, and his lasting impact on history, particularly Norway's experience during World War II, continue to be subjects of study and reflection.

8.1. Personal Character

To his supporters, Quisling was regarded as an exceptionally conscientious administrator, knowledgeable and meticulous. They believed he deeply cared for his people and consistently upheld high moral standards. Conversely, his opponents viewed him as unstable, undisciplined, abrupt, and at times, threatening. It is plausible that he exhibited both sides of this spectrum: he was at ease among friends but displayed significant pressure when confronted by political adversaries, generally remaining shy and reserved in both contexts. During formal dinners, he often remained silent, occasionally interjecting with dramatic rhetorical flourishes. Indeed, he did not handle pressure well, frequently uttering over-dramatic sentiments when put on the spot. While typically open to criticism, he tended to perceive larger groups as engaging in conspiracies against him.

Post-war interpretations of Quisling's character are similarly diverse. After the war, collaborationist behavior was popularly attributed to mental deficiency, which left Quisling's clearly more intelligent personality an "enigma." He was alternatively seen as weak, paranoid, intellectually sterile, and power-hungry-ultimately "muddled rather than thoroughly corrupted." Psychiatrist Professor Gabriel Langfeldt famously stated that Quisling's ultimate philosophical goals "fitted the classic description of the paranoid megalomaniac more exactly than any other case [he had] ever encountered."

During his time in office, Quisling maintained an early routine, often completing several hours of work before arriving at his office between 9:30 and 10:00. He preferred to intervene in virtually all government matters, personally reading and actioning a surprising number of letters addressed to him or his chancellery. Quisling demonstrated independent thinking, made several key decisions on the spot, and, unlike his German counterpart, he adhered to procedure to ensure that government affairs remained "a dignified and civilized" process. He also took a personal interest in the administration of Fyresdal, his birthplace. Despite his position, he did not live extravagantly and many gifts he received went unused. Party members did not receive preferential treatment, though Quisling himself did not share in the wartime hardships endured by his fellow Norwegians.

8.2. The Term "Quisling"

Vidkun Quisling's name has transcended his individual history to become a derogatory term synonymous with "collaborator" or "traitor" in several languages. This widely recognized term was coined by the British newspaper The Times in its lead article on April 15, 1940, titled "Quislings everywhere." The noun "quisling" rapidly gained currency and persisted, with the back-formed verb "to quisle" (meaning to commit treason) also seeing use for a period during and after World War II. The term reflects the deep contempt with which Quisling's conduct has been regarded, both at the time of his actions and in contemporary historical assessment. One notable black joke illustrating this societal understanding depicts Quisling visiting Berlin: Quisling says, "I'm Quisling," to which Hitler replies, "And your name?" The humor lies in Hitler interpreting "Quisling" as a common noun for "traitor."

8.3. Criticisms and Controversies

Vidkun Quisling's actions and ideology have drawn extensive criticism and remain the subject of significant historical debate. His collaboration with Nazi Germany involved profound legal and ethical violations, leading to his conviction for treason and other severe charges. A key controversy centers on his active role in the persecution of Jews in Norway. Despite his public rhetoric about not supporting extermination and suggesting a "new Jewish homeland" in Madagascar, his regime implemented anti-Jewish policies, including the registration and confiscation of Jewish property through a law enacted on October 26, 1942. Although the large-scale deportations of Jews to concentration camps in occupied Poland were primarily a German initiative, Quisling's government provided assistance and he publicly took credit for these actions, which contributed directly to the tragic fate of hundreds of Norwegian Jews in extermination camps like Auschwitz. This involvement highlights his complicity in human rights abuses under the occupation.

His attempt to seize power during the German invasion in 1940, proclaimed via radio, was unprecedented and immediately branded him as a traitor to his nation. His subsequent leadership of a puppet government under the German Reichskommissariat ReichskommissariatGerman stripped Norway of its sovereignty and undermined its democratic institutions. Policies implemented by his regime, such as censorship, the suppression of the Norwegian resistance movement, and forced youth enlistment, further eroded civil liberties and sparked widespread societal opposition. Even his attempts to negotiate greater independence for Norway from German control were seen as serving the occupier's interests rather than genuine national liberation. The trial that followed World War II meticulously laid out the charges of high treason, murder, and embezzlement, exposing the depth of his betrayal and the devastating consequences of his collaboration.

8.4. Historical Significance and Impact

Vidkun Quisling's life and actions have left an indelible mark on Norwegian society and history. His leadership of the collaborationist regime during the German occupation fundamentally challenged Norway's national identity and democratic values. The period of his governance is remembered as a dark chapter, characterized by foreign domination and internal division. The swift and decisive legal purge in Norway after World War II that followed the liberation, culminating in Quisling's execution, underscored the nation's resolve to hold collaborators accountable and restore its democratic principles.

Despite his ultimate failure and the contempt his name now carries, Quisling's life remains one of the most extensively documented among Norwegians. His philosophical works, particularly "Universism" and later writings like Universistic Aphorisms and Eternal Justice, offer insights into his complex, albeit flawed, worldview. His former residence in Oslo, a mansion on Bygdøy that he named "Gimlé" after a place in Norse mythology where survivors of Ragnarök were to live, was later renamed Villa Grande and transformed into a Holocaust museum, serving as a poignant reminder of the atrocities committed under his regime and the enduring importance of tolerance and remembrance. The complete eradication of the Nasjonal Samling as a political force after the war further cemented the rejection of Quisling's ideology in Norway.