1. Overview

Valerius Maximus was a Roman Latin writer of the 1st century AD, known for his collection of historical anecdotes, Facta et Dicta MemorabiliaMemorable Deeds and SayingsLatin (also known as Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings). He wrote during the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14 AD to 37 AD), likely publishing his work in the later years of Tiberius's rule, specifically between 31 AD and 37 AD, following the downfall of Sejanus. His work served as a commonplace book, providing historical examples for rhetorical schools to enhance speeches. Despite criticisms regarding its historical accuracy and perceived flattery towards imperial figures, the work gained immense popularity during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, becoming one of the most widely copied Latin prose texts and influencing numerous scholars and artists.

2. Biography

Valerius Maximus's life is largely undocumented, with much of what is known derived from his own writings. His background and connections with the imperial court and prominent figures of his time reveal insights into the social dynamics and political climate of early Imperial Rome.

2.1. Early Life and Background

Valerius Maximus came from a humble and undistinguished family, suggesting he did not belong to the prestigious patrician Valerii Maximi of the Roman Republic. Scholars like John Briscoe consider it "unlikely in the extreme" that he was part of this patrician line, suggesting instead that he might have been a descendant of the plebeian Valerii Tappones or Triarii, or perhaps gained Roman citizenship through the patronage of a Republican Valerius. His career and social standing were significantly advanced through the patronage of Sextus Pompeius, who served as consul in 14 AD and later as proconsul of Asia. Valerius accompanied Pompeius on his journey to the East in 27 AD. Pompeius was a prominent figure, central to a literary circle that included the poet Ovid, and was also a close friend of Germanicus, a highly literary prince of the imperial family.

2.2. Relationship with the Imperial Court and Political Stance

Valerius Maximus's relationship with the imperial household and his political views remain a subject of scholarly debate. He has been characterized by some as a sycophantic flatterer of Emperor Tiberius, similar to poets like Martial. This perception stems from passages in his work that appear to praise Tiberius lavishly. For instance, he refers to Tiberius as salutaris princepsbeneficial princeLatin. However, others argue that, when viewed in the context of the political rhetoric of his era, his references to the imperial administration are not excessively extravagant.

Nevertheless, the historian H. J. Rose critically stated that Valerius "cares nothing for historical truth if by neglecting it he can flatter Tiberius, which he does most fulsomely." While allusions to Julius Caesar's assassins and to Augustus are generally considered conventional for his time, the most conspicuous example of his perceived obsequiousness is his "violently rhetorical tirade" against Sejanus. The presence of both flattery towards Tiberius and condemnation of Sejanus in his work suggests its publication occurred after Sejanus's downfall, aligning with the period of 31 to 37 AD, when Tiberius's power was solidified.

3. Major Work: Facta et Dicta Memorabilia

Valerius Maximus's most notable contribution is his monumental work, Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IXNine Books of Memorable Deeds and SayingsLatin, commonly known as Facta et Dicta MemorabiliaMemorable Deeds and SayingsLatin. This compendium of historical anecdotes served a specific purpose and displayed a distinctive literary style.

3.1. Nature and Purpose

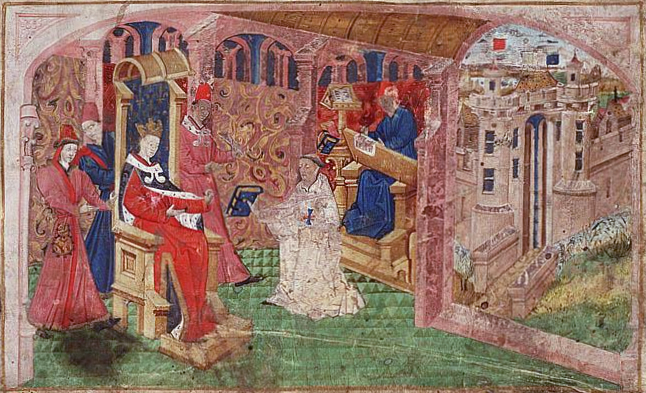

The primary intention behind Facta et Dicta MemorabiliaMemorable Deeds and SayingsLatin was to serve as a commonplace book, or an exempla collection, for use in schools of rhetoric. In Roman rhetorical education, students were trained to embellish their speeches with historical references and moral examples. Valerius Maximus's collection provided a ready-made compilation of such anecdotes, making it an invaluable resource for budding orators. Each story within the collection was designed to illustrate a particular virtue, vice, merit, or demerit, offering practical ethical lessons alongside historical knowledge.

3.2. Structure and Style

The work is generally divided into nine books, though some traditions refer to a tenth book, which is largely considered a later addition by a grammarian. The stories are arranged thematically rather than chronologically or strictly historically. Each book is further segmented into sections, with titles explicitly stating the moral or thematic point being illustrated, such as courage, clemency, moderation, cruelty, omens, or good fortune.

Valerius Maximus's literary style is characteristic of the Silver Latin age, a period marked by a shift towards more elaborate and rhetorical prose. His writing often prioritizes novelty and rhetorical flourish over direct and simple statements, sometimes resulting in a dense and obscure quality. His diction is often described as poetic, employing strained uses of words, invented metaphors, startling contrasts, and nuanced allusions. He frequently utilizes various grammatical and rhetorical figures of speech, reflecting his background as a professional rhetorician.

3.3. Sources and Content

The majority of the anecdotes in Facta et Dicta MemorabiliaMemorable Deeds and SayingsLatin are drawn from Roman history. However, each thematic section includes an appendix featuring extracts from the annals of other peoples, primarily the Greeks. Valerius Maximus often highlights a prevailing sentiment among Roman writers of his time: a belief that contemporary Romans had degenerated compared to their Republican ancestors, yet still maintained moral superiority over other civilizations, especially the Greeks.

His principal sources include prominent Roman historians and writers such as Cicero, Livy, Sallust, and Pompeius Trogus, with Cicero and Livy being particularly significant. While Valerius Maximus's treatment of his source material is often criticized for its carelessness, inaccuracies, and chronological errors, his collection remains valuable. Despite his confusions, contradictions, and anachronisms, the excerpts effectively serve their rhetorical purpose as illustrations for specific circumstances or qualities. Furthermore, his work uniquely preserves glimpses into the poorly documented reign of Tiberius, fragmentary information on Hellenistic art, and insights into the early imperial consensus regarding the necessity of orderly Roman religion for political stability.

4. Legacy and Reception

The influence of Valerius Maximus's Facta et Dicta MemorabiliaMemorable Deeds and SayingsLatin endured for centuries, profoundly impacting education, literature, and scholarly pursuits from the Middle Ages to the modern era.

4.1. Medieval and Renaissance Influence

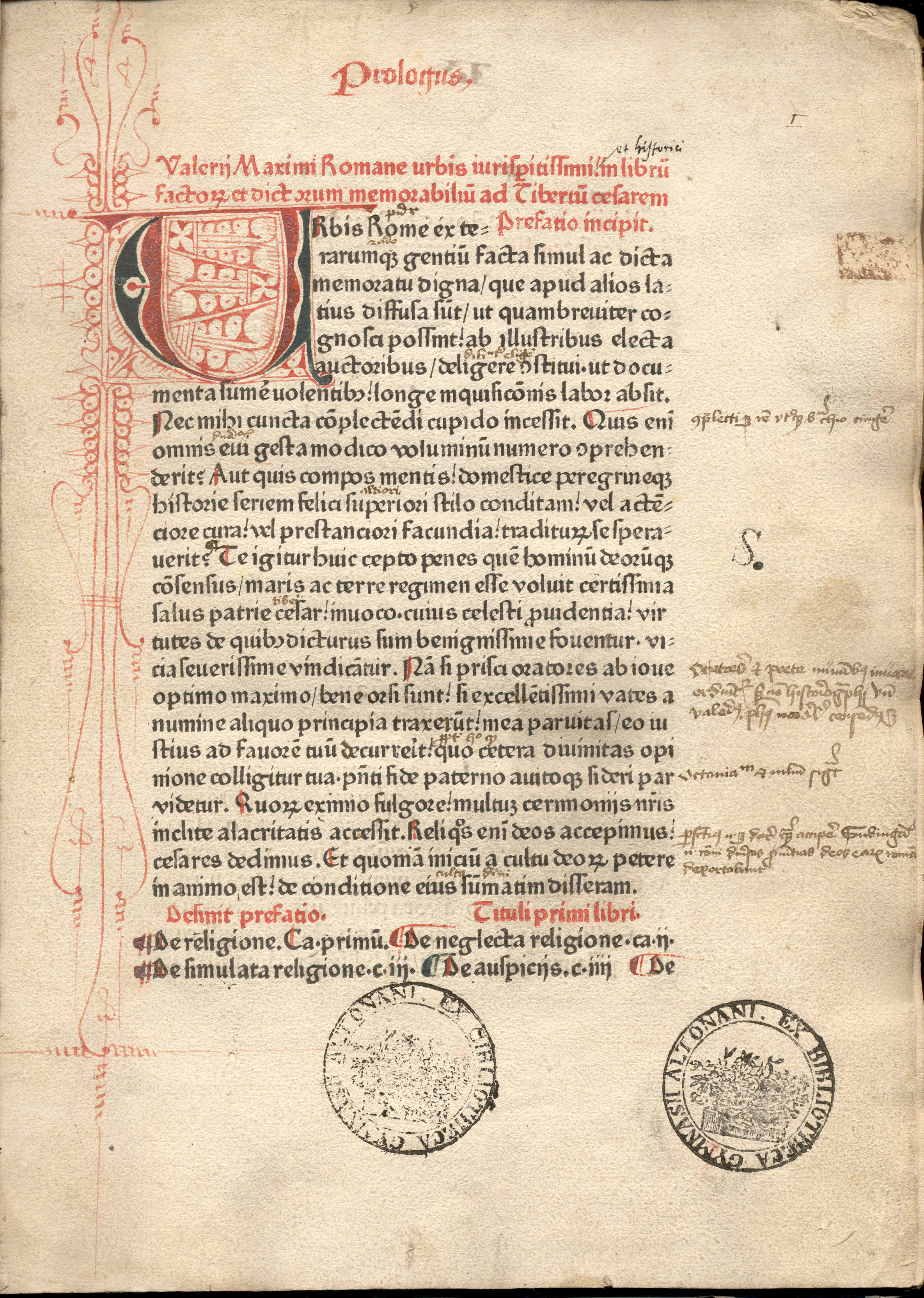

Valerius Maximus's collection was extensively used in schools throughout the Middle Ages due to its didactic nature and readily accessible anecdotes. Its widespread popularity is evidenced by the remarkable number of surviving medieval manuscripts, over 600, a figure second only to the grammarian Priscian. Some scholars, such as B. G. Niebuhr, even claimed it was "the most important book next to the Bible" during that period.

Like many schoolbooks, it was often abridged into epitomes. A complete epitome from the 4th or 5th century, attributed to Julius Paris, and a partial one by Januarius Nepotianus, have survived. During the Carolingian Renaissance, important manuscripts, such as one corrected by Lupus Servatus of Ferrières, helped preserve and disseminate the text. In the Middle Ages, the work was also read as a historical text. Its influence arguably reached its zenith during the Renaissance, when it became a central part of the Latin curriculum in its unabridged form. Notable authors like Dante utilized Valerius Maximus's work, for instance, in his account of the generosity and modesty of Pisistratus in Purgatory, Canto XV.

4.2. Later Editions, Manuscripts, and Academic Study

The survival of approximately 600 manuscripts, and 800 when epitomes are included, highlights the significant role Valerius Maximus played in Latin literature. While most manuscripts date from the late Middle Ages, about 30 predate the 12th century. The three oldest and most authoritative manuscripts for establishing the text are:

- Manuscript A: Housed at the Burgerbibliothek of Berne in Bern, Switzerland (n°366).

- Manuscript L: Located at the Laurentian Library in Florence, Italy (Ashburnham 1899). Both A and L were copied in northern France during the 9th century and derive from a common source.

- Manuscript G: Found at the Royal Library of Belgium in Brussels, Belgium (n°5336). This manuscript was likely written at Gembloux Abbey (south of Brussels) in the 11th century. According to John Briscoe, Manuscript G has a different lineage from A and L, as it does not share several errors present in both A and L.

Early critical editions of Valerius Maximus's work include those by C. Halm (1865) and C. Kempf (1888), which also incorporated the epitomes by Paris and Nepotianus. More recent editions include those by R. Combès (from 1995 onwards, with a French translation), J. Briscoe (1998), and D.R. Shackleton Baily (2000, with an English translation). The work has continued to be a subject of academic inquiry, with significant studies such as W. Martin Bloomer's Valerius Maximus and the Rhetoric of the New Nobility (1992), Clive Skidmore's Practical Ethics for Roman Gentlemen: the Work of Valerius Maximus (1996), and Hans-Friedrich Mueller's Roman Religion in Valerius Maximus (2002).

Beyond academic circles, the work also reached a broader audience through translations. A Dutch translation published in 1614 was notably read by artists like Rembrandt and their patrons. This translation spurred interest in new artistic subjects, such as the story of Artemisia II of Caria drinking her husband's ashes, demonstrating the work's cultural impact even centuries after its creation.

4.3. Criticism and Controversy

Despite its enduring popularity, Valerius Maximus's work has faced significant criticism, primarily concerning its historical integrity and the author's perceived political leanings. Critics frequently point out the work's historical inaccuracies, chronological errors, and inconsistencies. Valerius is often accused of being careless and imprecise in his handling of historical material, sometimes blending facts, contradictions, and anachronisms.

A major point of contention is his perceived sycophancy towards the imperial family, particularly Emperor Tiberius. As previously mentioned, critics like H. J. Rose accused him of prioritizing flattery over historical truth, making his work an unreliable source for objective historical analysis. This aspect of his writing has led to ongoing scholarly debate regarding his motivations and the extent to which his political agenda influenced his narrative.