1. Early Life and Background

Valdemar II's early life was shaped by his royal lineage and the political landscape of Denmark and the Holy Roman Empire, preparing him for his eventual ascent to the throne.

1.1. Birth and Family

Valdemar II was born on 28 June 1170, the second son of King Valdemar I and Sophia of Polotsk. His family belonged to the House of Estridsen, a prominent Danish royal dynasty. Through his mother, Sophia, he was connected to the nobility of Polotsk and Minsk, further solidifying his ties within the broader European aristocracy.

1.2. Childhood and Education

At the age of twelve, following the death of his father in 1182, Valdemar was appointed Duke of Southern Jutland (dux slesvicensisLatin), which corresponds to the Duchy of Schleswig. His regent during this formative period was Bishop Valdemar Knudsen, an illegitimate son of King Canute V of Denmark. Bishop Valdemar, an ambitious figure, initially masked his own aspirations by acting in the young duke's name.

1.3. Early Political and Military Activities

As Duke of Southern Jutland, Valdemar quickly became involved in significant political and military engagements. In 1192, Bishop Valdemar Knudsen, upon being named Prince-Archbishop of Bremen, revealed his true intentions to overthrow King Canute VI of Denmark (Valdemar II's elder brother) with the support of German nobility, aiming to seize the Danish throne for himself. Recognizing this threat, Duke Valdemar invited the bishop to Aabenraa in 1192, prompting the bishop to flee to Norway to avoid arrest. The following year, Bishop Valdemar, backed by the House of Hohenstaufen, assembled a fleet of 35 ships and raided Danish coasts, asserting his claim to the throne as the son of King Canute V. However, he was captured by King Canute VI in 1193 and imprisoned, first in Nordborg (1193-1198) and then in the tower at Søborg Castle on Zealand until 1206. He was eventually released through the intervention of Dagmar of Bohemia, Valdemar's wife, and Pope Innocent III, after swearing not to interfere in Danish affairs again.

Duke Valdemar also faced a formidable challenge from Count Adolf III of Holstein. Adolf attempted to incite other German counts to reclaim Southern Jutland from Denmark and support Bishop Valdemar's bid for the throne. With the bishop once again in custody, Duke Valdemar turned his attention to Count Adolf. Leading his own troops, he marched south, captured Adolf's new fortress at Rendsburg, and decisively defeated and captured the count at the Battle of Stellau in 1201, imprisoning him alongside Bishop Valdemar. Two years later, due to illness, Count Adolf secured his release by ceding all of Schleswig, north of the Elbe, to Duke Valdemar. In November 1202, Valdemar's elder brother, King Canute VI, died unexpectedly and childless, paving the way for Valdemar's succession.

2. Reign and Major Achievements

Valdemar II's reign was characterized by significant territorial expansion, strategic foreign policy, and groundbreaking legal reforms that profoundly shaped Denmark.

2.1. Accession and Consolidation of Power

Following the unexpected death of his brother, King Canute VI, in November 1202, Duke Valdemar was proclaimed king at the Jutland Assembly (landstingDanish). At the time, the neighboring Holy Roman Empire was embroiled in a civil war, with two rival claimants to the throne: Otto IV of the House of Guelf and King Philip of the House of Hohenstaufen. Valdemar II strategically allied himself with Otto IV against King Philip, securing an important diplomatic position early in his reign.

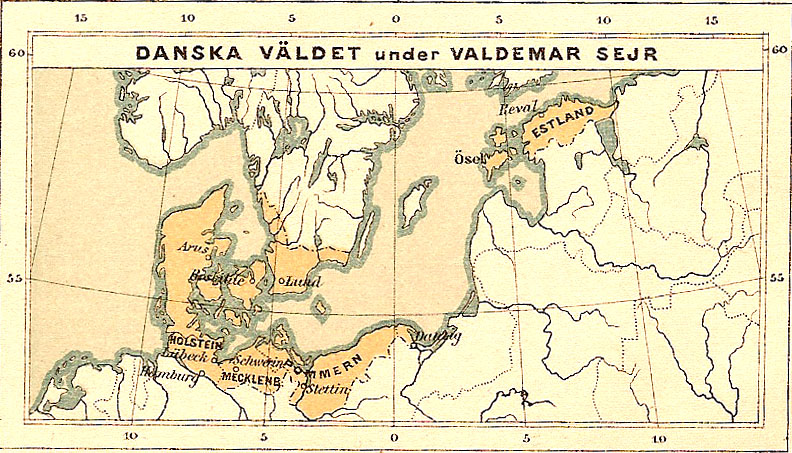

2.2. Territorial Expansion and Baltic Dominance

Valdemar's extensive campaigns in northern Germany and the Baltic region, particularly the crusades in Estonia, were central to his ambition of establishing Danish dominance.

Valdemar II aggressively expanded Danish influence and control. In 1203, he invaded and conquered Lübeck and Holstein, significantly expanding Danish territories. In 1204, he intervened in the Norwegian succession, leading a Danish fleet and army to Viken in Norway to support Erling Steinvegg, a pretender to the Norwegian throne. This intervention led to the second Bagler War, which lasted until 1208. The conflict temporarily resolved the Norwegian succession issue, with the Norwegian king acknowledging allegiance to Denmark.

Valdemar's reign also saw disputes with the Papacy over the appointment of the Prince-Archbishop of Bremen. In 1207, a majority of Bremian capitulars elected Bishop Valdemar Knudsen as prince-archbishop, while a minority fled to Hamburg. King Philip of Swabia recognized Bishop Valdemar, hoping to gain an ally against Valdemar II. However, Valdemar II and the dissenting capitulars protested to Pope Innocent III. When Bishop Valdemar defied the Pope's order to await his decision in Rome, he was excommunicated and dismissed as Bishop of Schleswig in 1208. Valdemar II then supported Burkhard, Count of Stumpenhausen, as a rival prince-archbishop, investing him with regalia, though its effect was limited to the territory north of the Elbe. In 1209, Innocent III finally approved the consecration of Nicholas I of Schleswig, a close confidant of King Valdemar, as the new bishop. In 1214, Valdemar appointed Bishop Nicholas I as Chancellor of Denmark.

Valdemar II continued his military campaigns, invading the prince-archiepiscopal territory south of the Elbe in 1214 and conquering Stade. Although Prince-Archbishop Valdemar briefly recaptured the city, Valdemar II quickly regained it, building a bridge over the Elbe and fortifying a forward post in Harburg upon Elbe. In 1209, Otto IV persuaded Valdemar II to withdraw north of the Elbe, urged Burkhard to resign, and expelled Prince-Archbishop Valdemar. The conflict over Bremen continued, with various figures contesting the archiepiscopal seat. Valdemar II recaptured Stade in 1211, only to lose it again in 1213. In 1216, Valdemar II and his Danish troops ravaged the County of Stade and conquered Hamburg. Two years later, Valdemar II allied with Gerhard I, the new Prince-Archbishop, to expel Henry V and Otto IV from the Prince-Archbishopric. Prince-Archbishop Valdemar finally resigned and entered a monastery. Valdemar's support for Emperor Frederick II was rewarded with the emperor's recognition of Danish rule over Schleswig and Holstein, all of the Wendish lands, and Pomerania, marking the zenith of Danish territorial power.

2.2.1. Campaigns in Northern Germany

Valdemar II's campaigns in Northern Germany were a series of conquests and subsequent losses that defined the limits of Danish expansion. After his initial successes in Holstein and Lübeck, his involvement in the Bremen archiepiscopal dispute led to prolonged conflicts. Despite gaining significant territories and imperial recognition, his ambitions faced strong resistance. In 1223, Valdemar and his eldest son, Prince Valdemar, were abducted by Count Henry I of Schwerin (Heinrich der SchwarzeGerman) while hunting on the island of Lyø. Henry demanded the return of lands conquered in Holstein and that Denmark become a vassal of the Holy Roman Emperor. Danish envoys refused, leading to war. During Valdemar's imprisonment, most of the German territories broke away from Danish control. Danish armies dispatched to maintain order were defeated, notably at Mölln in 1225. To secure his release, Valdemar was forced to acknowledge the independence of these territories, pay 44,000 silver marks, and promise not to seek revenge.

Upon his release, Valdemar appealed to Pope Honorius III, who declared his forced oath void. Valdemar immediately sought to restore his German territories, concluding a treaty with his nephew Otto I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. However, a series of Danish defeats, culminating in the decisive Battle of Bornhöved on 22 July 1227, cemented the loss of Denmark's North German territories. Valdemar himself narrowly escaped capture due to the chivalrous actions of a German knight.

2.2.2. The Crusades in Estonia and the Battle of Lindanise

In 1219, the Livonian Knights, struggling to Christianize the peoples of the eastern Baltic, sought Valdemar's assistance. Pope Honorius III elevated Valdemar's invasion of Estonia into a crusade. Valdemar assembled a massive army and a fleet of 1500 ships to transport his forces eastward.

Upon landing in Estonia, near modern-day Tallinn, the Estonian chiefs initially agreed to acknowledge the Danish king as their overlord, and some even accepted baptism, signaling a promising start. However, three days later, on 15 June 1219, while the Danes were attending mass, thousands of Estonians launched a surprise attack on the Danish camp from all sides. Confusion ensued, and Valdemar's crusade seemed on the verge of collapse. Fortunately, Vitslav of Rügen rallied his men from a second camp and attacked the Estonians from the rear, turning the tide of the battle.

During the Battle of Lindanise, legend states that whenever Bishop Sunesen raised his arms, the Danes surged forward, but when his arms grew tired and fell, the Estonians pushed the Danes back. Attendants rushed to support his arms, and the Danes advanced again. At the height of the battle, Bishop Sunesen prayed for a sign, and a red cloth with a white cross drifted down from the sky just as the Danes began to retreat. A voice was heard to proclaim, "When this banner is raised on high, you shall be victorious!" Inspired, the Danes surged forward and won the battle, with thousands of Estonians dead on the field. Estonia was subsequently incorporated into the Danish realm. While some accounts suggest Estonians were forcibly baptized, an in-depth study of the Liber Census DaniæLatin by historian Edgar Sachs indicates that many Estonians voluntarily converted to Christianity.

Valdemar ordered the construction of a large fortress at Reval, near the battle site. A city eventually grew around this hilltop castle, which is still known as Tallinn, meaning "Danish-castle/town" in the Estonian language. The red banner with a white cross, known as the Dannebrog, has been the national flag of Denmark since 1219 and is recognized as Europe's oldest flag design still in modern use.

2.3. Legal Reforms and Social Impact

Following his military setbacks, Valdemar II focused on internal reforms, notably introducing feudalism and codifying Danish law.

2.3.1. Introduction of Feudalism

One of the major changes Valdemar instituted was the formal introduction of a feudal system in Denmark. Under this system, the king granted properties to men in exchange for their service, primarily military. This arrangement significantly increased the power of the noble families (højadelenDanish) and led to the rise of lesser nobles (lavadelenDanish), who came to control much of Denmark. A critical consequence of this reform was the loss of traditional rights and privileges for free peasants, which they had enjoyed since the Viking Age. This shift had a profound impact on social equity, consolidating power and land ownership in the hands of the nobility at the expense of the common populace.

2.3.2. The Code of Jutland (Jyske Lov)

Valdemar II dedicated the remainder of his life to compiling a comprehensive legal code for Jutland, Zealand, and Skåne. This monumental work, known as the Code of Jutland (Jyske LovDanish), served as Denmark's primary legal code until 1683. Its creation represented a significant departure from the long-standing tradition of local law-making at regional assemblies (landtingDanish), bringing standardization to the Danish legal system. The Code of Jutland outlawed several archaic methods of determining guilt or innocence, including trial by ordeal and trial by combat, marking a step towards a more rationalized justice system. The code was formally approved at a meeting of the nobility at Vordingborg Castle in 1241, shortly before Valdemar's death.

3. Personal Life

Valdemar II's personal life, marked by his marriages and the succession of his children, played a significant role in the dynastic politics of Denmark.

3.1. Marriages and Issue

Before his first marriage, Valdemar was betrothed to Rixa of Bavaria, daughter of the Duke of Saxony, but this arrangement did not materialize.

In 1205, Valdemar married his first wife, Dagmar of Bohemia, also known as Margaret of Bohemia. She was the daughter of King Ottokar I of Bohemia and his first wife, Adelaide of Meissen. Queen Dagmar quickly became popular with the Danes due to her gentle and pious nature. With Dagmar, Valdemar had one surviving son:

- Valdemar the Young (1209 - 28 November 1231), whom he elevated as co-king at Schleswig in 1218. Valdemar the Young married Eleanor of Portugal in 1229. He tragically died in 1231 after being accidentally shot during a hunting expedition at Refsnæs in North Jutland.

- A stillborn son (1212).

Queen Dagmar herself died in childbirth in 1212. According to old folk ballads, on her deathbed, she implored Valdemar to marry Kirsten, the daughter of Karl von Rise, rather than the "beautiful flower," Berengária of Portugal (Bengerd), foreseeing that Berengária's sons would fight over the throne and bring trouble to Denmark.

After Dagmar's death, to strengthen relations with Flanders, Valdemar married his second wife, Berengária of Portugal, in 1214. She was the orphaned daughter of King Sancho I of Portugal and Dulce of Aragon, and sister of Ferdinand, Count of Flanders. Queen Berengária was renowned for her beauty but was generally disliked by the Danes for her perceived hard-heartedness. She also died prematurely in childbirth in 1221. Both of Valdemar's wives are prominent figures in Danish ballads and myths: Dagmar is depicted as the soft, pious, and popular ideal wife, while Berengária is portrayed as beautiful yet haughty.

With his second wife, Berengária of Portugal, Valdemar had the following children:

- Eric IV, King of Denmark (1216 - 10 August 1250). He became Duke of Schleswig and then co-ruler in 1231. He married Jutta of Saxony in 1239 and had six children, including Sophia and Ingeborg.

- Sophie of Denmark (1217 - 2 November 1247), who married John I, Margrave of Brandenburg in 1225.

- Abel, King of Denmark (1218 - 29 June 1252). He became Duke of Schleswig in 1231. He married Matilda of Holstein in 1237 and had four children.

- Christopher I, King of Denmark (1219 - 29 May 1259). He became Duke of Lolland and Falster in 1231. He married Margaret Sambiria in 1248 and had three children, including Eric V.

- A stillborn child (1221).

Valdemar II also had illegitimate children with various women:

- With Helena Guttormsdotter, a Swedish noblewoman and wife of a Danish noble, he had:

- Knud Valdemarsen (1207 - 15 November 1260), who became Duke of Estonia in 1219, Blekinge in 1232, and later Lolland. He had three children.

- With an unknown concubine, he had:

- Niels Valdemarsen (died 1218), who became Count of Halland (1216-1218). He married Oda of Schwerin and had one son.

Valdemar the Young, Valdemar II's eldest son and co-king

Eric IV, Valdemar II's second son and successor

4. Death

King Valdemar II died on 28 March 1241, at the age of 70. He passed away at Vordingborg Castle, shortly after the approval of the Code of Jutland. His body was laid to rest beside his first wife, Queen Dagmar, at Ringsted in Zealand.

5. Legacy and Assessment

Valdemar II holds a central and complex position in Danish history, remembered both for his significant achievements and the challenges that followed his reign.

5.1. Positive Contributions

Valdemar II's positive legacy is multifaceted. He is widely celebrated as "the king of Dannebrog" due to the legend of the Danish flag's miraculous appearance during the Battle of Lindanise. This association has deeply intertwined him with a foundational national symbol. As a legislator, his most enduring contribution was the Code of Jutland, which standardized Danish law for centuries and remains a testament to his vision for a unified legal system. His reign saw remarkable territorial expansion, establishing Denmark as a dominant power in the Baltic region and Northern Germany, a period often viewed as a golden age of Danish influence. Since 1912, June 15 has been officially recognized as ValdemarsdagDanish (Valdemar's Day), one of 33 annual Flag Days in Denmark where the Dannebrog is raised in celebration. The Estonian capital Tallinn features the Danish King's Garden at Toompea, commemorating the legendary birthplace of the Dannebrog, with annual celebrations held on June 15. The Dannebrog itself is recognized as Europe's oldest flag design still in modern use.

5.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his celebrated achievements, Valdemar II's reign is also subject to criticism and controversy. The disastrous loss of most of Denmark's North German territories after his abduction and the Battle of Bornhöved significantly diminished the empire he had built. This setback is seen by some as a major strategic failure that led to a period of decline. Furthermore, the introduction of feudalism, while centralizing power, had profound social consequences. The system increased the power of noble families and led to the loss of traditional rights and privileges for free peasants, who had enjoyed greater autonomy since the Viking era. This fundamental shift in land tenure and social structure created lasting inequalities and is a point of critical assessment regarding his impact on social progress. The civil wars and dissolution that followed his death further highlight the instability that characterized the end of his reign, leading posterity to view him as the last king of a "golden age" before a period of internal strife.

6. Influence on Danish Identity

Valdemar II's reign had a lasting influence on the development of Danish identity, particularly in the spheres of law, national consciousness, and cultural symbols. The Code of Jutland laid the foundation for a unified Danish legal system, fostering a sense of shared governance and national cohesion. The legend of the Dannebrog's origin during the Battle of Lindanise, inextricably linked to Valdemar, became a powerful national myth, symbolizing divine favor and national unity. This narrative has been instrumental in shaping Danish national consciousness and pride, with the flag becoming a central emblem. Valdemar II is remembered in historical narratives as a pivotal figure who, despite later setbacks, significantly contributed to the formation of the Danish state and its enduring symbols. His reign is often seen as a benchmark for Danish power and cultural distinctiveness in the medieval period.