1. Early Life

Tyson Gay's early life in Kentucky was marked by a strong family athletic background and a developing interest in sprinting, influenced by his older sister.

1.1. Childhood and Background

Tyson Gay was born on August 9, 1982, in Lexington, Kentucky, and is the only son of Daisy Gay and Greg Mitchell. Athletics ran in his family; his grandmother competed for Eastern Kentucky University, and his mother, Daisy, also participated in sports during her youth. Gay's older sister, Tiffany, was a dedicated sprinter who had a successful high school career. Encouraged by their mother, Tyson and Tiffany often raced against each other, training diligently at school and on the hills near their home. This sibling rivalry was a significant motivator for Gay, who later credited his sister's quick reaction time for inspiring him to improve. During his childhood, Gay also played for a local baseball club, where his speed made him proficient at stealing bases. He began focusing on track and field at the age of 15, in his third year of middle school, following his sister's involvement in a track club.

1.2. Education and Amateur Career

Gay attended Lafayette High School, where he joined the track team and won the 100m Kentucky state championship for three consecutive years from 1999. His high school personal bests were 10.46 s in the 100m and 21.23 s in the 200m. He also played American football during the off-season. Despite his athletic talent, Gay was not a particularly studious child and struggled to achieve the academic grades required for entry into a Division I sports college. At the time, his weight was around 143 lb (65 kg), which was considered light for a sprinter, and he did not receive recruitment offers from top-tier universities.

In 2001, at a track event, Gay met trainer Lance Brauman, who convinced him to attend Barton County Community College in Great Bend, Kansas. There, Gay's performance significantly improved. In 2002, his 100m and 200m times dropped to 10.08 s and 20.21 s respectively, albeit with wind assistance. His legal personal bests also improved to 10.27 s in the 100m and 20.88 s in the 200m. He won the 100m at the NJCAA National Championship that year, and also secured two titles (60m and 200m) at the NJCAA Division I Indoor Championships. He also made his debut at the US National Championships, finishing fifth in the 100m with a wind-aided 10.28 s. During his time at Barton, he formed a close bond and training partnership with Jamaican sprinter Veronica Campbell-Brown.

In 2003, injuries hampered Gay's season, preventing him from defending his NJCAA titles (he finished third in the 100m and second in the 200m). His coach, Lance Brauman, moved to the University of Arkansas as a sprint coach, and Gay followed him, enrolling at Arkansas in 2003 to study sociology and marketing.

At the NCAA Men's Indoor Track and Field Championship in March 2004, Gay placed fourth in the 60m with 6.63 s and fifth in the 200m with 20.58 s. The NCAA Men's Outdoor Track and Field Championship in June proved more successful, as he became Arkansas' first 100m NCAA champion, setting a school record of 10.06 s. His performance contributed to the Arkansas athletic team winning the NCAA Championship. At the 2004 US Olympic Trials, he reached the semi-finals of the 100m and set a 200m personal best of 20.07 s in the qualifying stages. A hamstring injury due to dehydration forced him to withdraw from the 200m final, but he viewed the trials as a learning experience. By the end of 2004, he was ranked the eighth fastest 100m runner and fourth fastest 200m sprinter in the U.S.

In his final amateur year in 2005, Gay set a personal best and school record of 6.55 s in the 60m. He helped the university team to another NCAA outdoor victory, setting a new 200m personal best of 19.93 s in the qualifiers and finishing third in the finals behind his training partner Wallace Spearmon. Both their times were among the fastest in the world that year. Gay, Spearmon, Michael Grant, and Omar Brown also won the 4 × 100m relay with an Arkansas-record time of 38.49 s. In June 2005, Gay decided to turn professional, aiming for a spot on the US 200m team for the 2005 World Championships in Athletics. Following his testimony, the courts ruled that Brauman was guilty of helping athletes gain funds and credits they were not entitled to. As a result, Arkansas' two NCAA titles and all of Gay's college track times were annulled, though none of the athletes were charged with wrongdoing. Brauman continued to train Gay, providing guidance from prison.

2. Athletic Career

Tyson Gay's professional career saw him rise to become one of the world's elite sprinters, achieving significant victories and records, though it was also marked by injuries and later, doping controversies.

2.1. Professional Debut and Early Career

Upon turning professional, Gay entered the 2005 USA Outdoor Championships, where he secured a silver medal in the 200m with 20.06 s. He was selected to compete in the 200m at the 2005 World Championships in Athletics in Helsinki, where he finished fourth. This marked an unprecedented achievement for a single nation, with the United States taking the top four positions in the event (Justin Gatlin, Wallace Spearmon, John Capel, and Gay). Gay also participated in the 4 × 100m relay, but the team was disqualified due to a poor baton exchange. Later that month, he achieved a season's best of 10.08 s in the 100m at the Rieti Grand Prix.

He concluded the 2005 season by winning his first major championship title, a gold medal in the 200m at the 2005 IAAF World Athletics Final. His time of 19.96 s was his second fastest of the year and the fourth fastest globally. He defeated all three American sprinters who had beaten him at the World Championships, becoming the first athlete to defeat Justin Gatlin in the 200m that season.

The 2006 season saw Gay establish himself as a top contender in both the 100m and 200m. He became the 2006 US Outdoor Champion in the 100m after Justin Gatlin's first-place finish was later rescinded due to a doping violation. Gay significantly improved his 200m personal best by over two-tenths of a second at the IAAF Grand Prix in Lausanne, running 19.7 s, though he was beaten by Xavier Carter's 19.63 s. He continued to improve his 100m time, winning the Rethymno track meet with 9.88 s and later clocking 9.97 s at the Stockholm Grand Prix, finishing second to Asafa Powell. He also broke Michael Johnson's British all-comers 200m record with a 19.84 s win in London. His 100m personal best was further revised to 9.84 s at the Zürich Golden League meet, where Powell equaled his own world record of 9.77 s.

Gay's 200m performance at the 2006 IAAF World Athletics Final in Stuttgart was a highlight of his successful year. He won the event with another improved personal best of 19.68 s, making him the joint third-fastest 200m sprinter in history, alongside Frankie Fredericks. He also earned a bronze medal in the 100m. At the 2006 IAAF World Cup, Gay secured a gold medal in the 100m with a 9.88 s run and contributed to the 4 × 100m relay gold. By the end of 2006, with Gatlin banned, Gay dominated the U.S. rankings, holding six of the seven fastest 100m times and four of the top six 200m times. He was the second-fastest 100m runner globally, trailing only world record holder Powell. Reflecting on his development, Gay noted his preference for the 100m due to the prestige of being labeled "the fastest man in the world."

2.2. Major Competition Records

Tyson Gay's career was defined by his performances on the biggest stages of international track and field, where he achieved both monumental victories and faced significant challenges.

2.2.1. World Athletics Championships

Gay's most successful World Championships appearance came at the 2007 World Championships in Osaka, Japan. With his coach Jon Drummond, Gay aimed to challenge Asafa Powell's dominance in the 100m. He started the outdoor season with impressive wind-assisted runs of 9.79 s and 9.76 s. At the US National Championships, he equaled his 100m best of 9.84 s against a headwind and set a new 200m personal best of 19.62 s, the second-fastest time ever recorded at that point, trailing only Michael Johnson's world record.

In Osaka, the 100m final was highly anticipated. Gay won with 9.85 s, becoming the new 100m world champion, surpassing Derrick Atkins and Asafa Powell. He then doubled his gold medal count in the 200m, setting a new championship record of 19.76 s, beating Usain Bolt and Wallace Spearmon. Bolt acknowledged Gay's superior performance, stating, "I got beaten by the No. 1 man in the world. For the moment, he is unbeatable." Gay completed a historic triple gold haul by winning the 4 × 100m relay alongside Darvis Patton, Wallace Spearmon, and Leroy Dixon, with a world-leading time of 37.78 s. This feat replicated the achievements of Maurice Greene in 1999 and Carl Lewis in 1983 and 1987. Despite his success, Gay remained humble, expressing his desire to break the world record to solidify his place among the sport's greats. He was recognized as the 2007 IAAF Male World Athlete of the Year and the Track and Field News Men's Athlete of the Year.

At the 2009 World Championships in Athletics in Berlin, Gay entered the 100m final alongside Usain Bolt and Asafa Powell. Despite running a new American record of 9.71 s, the third-fastest time in history at that point, he finished second to Bolt, who shattered the world record with 9.58 s. Gay's time remains the fastest non-winning time in 100m history. He had been suffering from hip pain and had taken painkillers to compete. Due to the lingering hip injury, Gay withdrew from the 200m event to focus on the relay. However, the American 4 × 100m relay team was disqualified in the heats due to a baton exchange error, leaving Gay with only one silver medal from the championships.

2.2.2. Olympic Appearances

Gay's Olympic career was marked by significant challenges and disappointments. Leading up to the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, he aimed to win four gold medals, including adding the 400m to his repertoire. At the US Olympic Trials, he set a new American record of 9.77 s in the 100m heats, making him the third-fastest 100m sprinter ever. In the final, he ran a wind-aided 9.68 s, the fastest 100m time ever recorded under any conditions at the time. However, a severe hamstring injury suffered in the 200m trials forced him to withdraw from that event for the Olympics. In Beijing, the injury hampered his performance; he failed to qualify for the 100m final, finishing fifth in his semi-final with 10.05 s. He attributed this to his disrupted training schedule rather than the injury itself. Further disappointment followed in the 4 × 100m relay when he and Darvis Patton failed to complete a baton exchange in the heats, leading to disqualification. Gay took responsibility for the dropped baton, but Patton insisted it was his fault. Gay left the 2008 Olympics without a single medal.

At the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, Gay qualified for the 100m after finishing second at the U.S. Olympic trials with 9.86 s. The 100m final in London was the fastest Olympic race ever, with seven men running under ten seconds. Gay finished fourth with 9.8 s, missing a bronze medal by just one-hundredth of a second to compatriot Justin Gatlin. He was visibly upset, expressing his disappointment in the post-race interview. The 4 × 100m relay final initially brought Gay his first Olympic medal, a silver, as the American team (with Trell Kimmons, Justin Gatlin, and Ryan Bailey) set an American record of 37.04 s. However, this medal was later stripped due to Gay's doping violation.

In the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Gay ran the third leg for the USA 4 × 100m relay team, which also included Justin Gatlin, Mike Rodgers, and Trayvon Bromell. The team initially finished third, but was later disqualified due to a baton exchange violation (Rule 170.7) between Rodgers and Gatlin, where the baton touched Gatlin's hand before reaching the exchange zone. This disqualification meant Gay became the fastest man in history to not win an Olympic medal. The Canadian team was subsequently awarded the bronze.

2.2.3. Other International Competitions

Beyond the World Championships and Olympics, Gay achieved success in various other international events. He won the 100m and 4 × 100m relay golds at the 2006 IAAF World Cup in Athens. He also secured gold in the 200m at the 2006 IAAF World Athletics Final in Stuttgart and the 100m at the 2009 IAAF World Athletics Final in Thessaloniki. In 2010, he was part of the Americas team that won gold in the 4 × 100m relay at the 2010 IAAF Continental Cup in Split, Croatia.

Gay was a dominant force in the IAAF Diamond League series. He was the overall winner of the 100m Diamond Race in 2010. His individual Diamond League wins include the 100m in Gateshead, Stockholm, and London in 2010, and the 200m in Monaco in 2010. In 2012, he won the 100m in New York, Paris, and London. After his suspension, he returned to win the 100m at the 2015 Prefontaine Classic and the 100m at the 2015 adidas Grand Prix in New York, and the 4 × 100m relay in Monaco in 2015. He also won the 200m at the 2006 IAAF Golden League in Brussels and the 100m at the 2009 IAAF Golden League in Rome. In September 2016, Gay announced a bid to join the U.S. bobsleigh team by competing at the National Push Championships at the Calgary track, though he later withdrew from the competition.

2.3. Personal Best Records

Tyson Gay holds impressive personal bests across various sprint distances, solidifying his place among the fastest sprinters in history.

| Event | Time (s) | Wind (m/s) | Competition | Venue | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100m | 9.69 s | +2.0 | Shanghai Golden Grand Prix | Shanghai, China | September 20, 2009 | American record |

| 100m | 9.68 s | +4.1 | U.S. Olympic Trials | Eugene, Oregon, U.S. | June 29, 2008 | Wind-assisted |

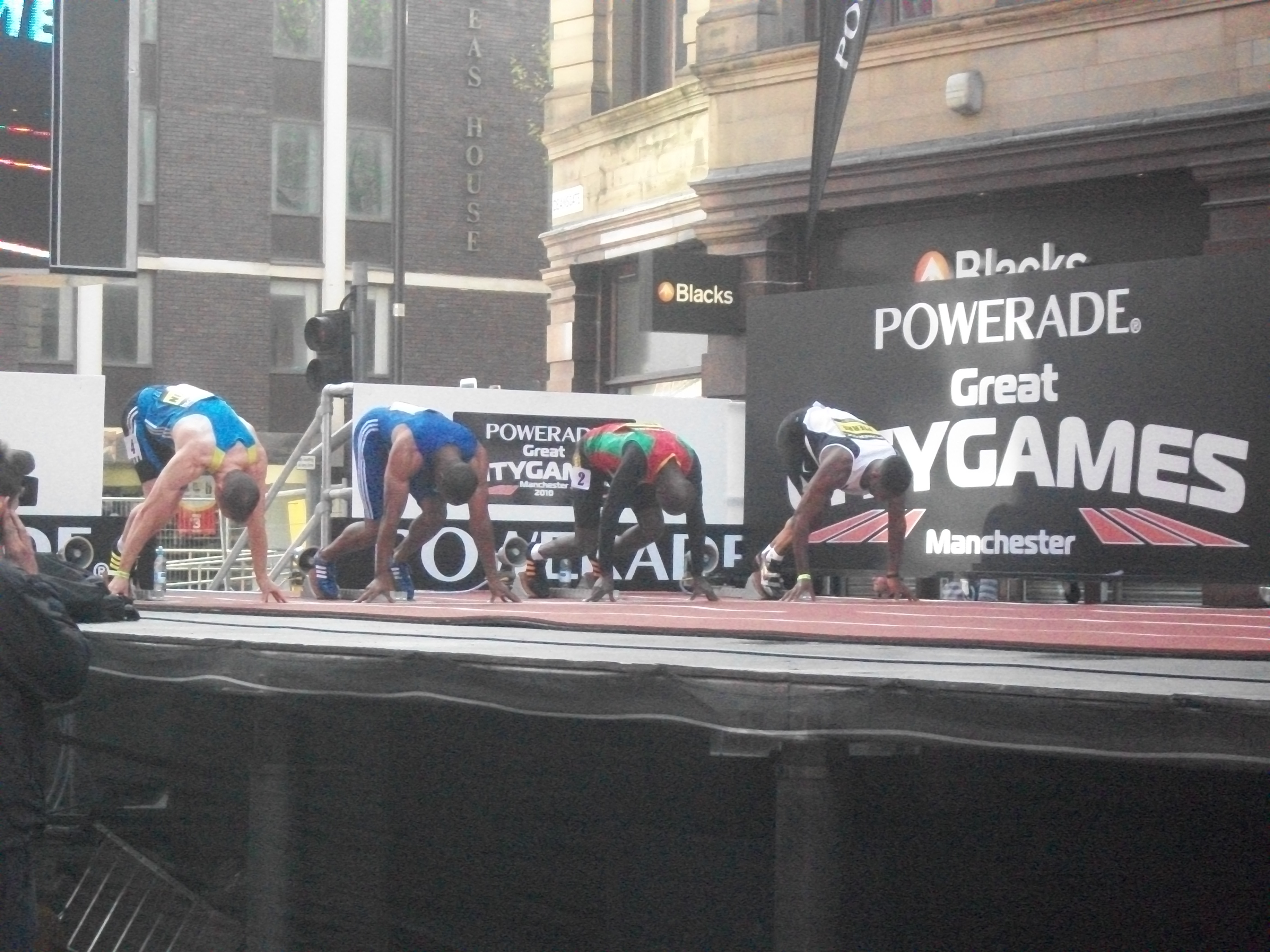

| 150m | 14.51 s | +1.5 | Great CityGames Manchester | Manchester, United Kingdom | May 15, 2011 | American record |

| 200m | 19.58 s | +1.3 | Adidas Grand Prix | New York, New York, U.S. | May 30, 2009 | |

| 200m straight | 19.41 s | -0.4 | Great CityGames Manchester | Manchester, United Kingdom | May 16, 2010 | World best |

| 400m | 44.89 s | n/a | Tom Jones Memorial Classic | Gainesville, Florida, U.S. | April 17, 2010 |

His 100m personal best of 9.69 s makes him tied for the second-fastest athlete over 100m ever, along with Yohan Blake of Jamaica, behind only Usain Bolt. His 19.58 s in the 200m ranks him among the top ten fastest 200m runners in history and is the fourth fastest in U.S. history. In 2010, Gay became the first sprinter in history to achieve times under 10 s in the 100m, under 20 s in the 200m, and under 45 s in the 400m. His sprint combination of 9.84 s (100m) and 19.62 s (200m), run over two days in 2007, was the best ever combination at that time.

2.4. Injuries and Comebacks

Throughout his career, Tyson Gay faced several significant injuries that impacted his ability to compete at his peak. A severe hamstring injury sustained during the 200m trials for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing forced him to withdraw from that event and significantly hampered his performance in the 100m and 4 × 100m relay at the Games, where he ultimately failed to win any medals. This injury persisted for several weeks, causing him to miss subsequent track meetings.

In 2011, a persistent hip injury led Gay to withdraw from the 2011 USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships. In July of that year, he underwent acetabular labrum surgery. This required a lengthy recovery period, and he did not compete again for almost a year. Despite these setbacks, Gay demonstrated resilience by making comebacks to elite competition, including qualifying for the 2012 Summer Olympics and continuing to compete at a high level in the Diamond League series.

3. Personal Life

Outside of his athletic pursuits, Tyson Gay's personal life has been marked by family devotion and profound tragedy.

3.1. Family Relationships

Tyson Gay resides in Clermont, Florida, a suburb of Orlando, Florida. He has a daughter named Trinity Gay with Shoshana Boyd, and he was deeply devoted to her care. When his former coach Lance Brauman was imprisoned for fraud, Gay extended support to Brauman's wife and daughter. His mother, Daisy, married Tim Lowe in 1995, expanding Gay's family to include two half-siblings, Seth and Haleigh Lowe.

A profound tragedy struck Gay's family on October 16, 2016, when his 15-year-old daughter, Trinity Gay, was fatally shot in the neck. She was an innocent bystander caught in a shootout between occupants of two cars in the parking lot of a Cook Out restaurant in Lexington, Kentucky. She died shortly thereafter at the University of Kentucky Medical Center.

3.2. Faith and Community

As a child, Tyson Gay attended the St. John Missionary Baptist Church, and he continues to attend services there when he returns home. He has publicly expressed his strong religious beliefs, stating, "I'm a religious man, so I really believe in my God-given ability, that I can do the unexpected. I really do believe I can break a record, or come close to it, or win a medal." This faith has been a guiding principle in his life and career, providing him with a sense of purpose and confidence.

4. Doping and Controversies

Tyson Gay's career was significantly overshadowed by doping violations, which led to severe consequences for his athletic record and sparked broader discussions about integrity in sports.

4.1. Drug Test Violations and Sanctions

On July 14, 2013, it was publicly announced that Tyson Gay had tested positive for a banned substance in May 2013. Gay openly admitted to the doping, attributing it to placing his trust in an unspecified third party who "let him down." In response to the revelation, Adidas, Gay's sponsor, immediately suspended his contract. Pending a final verdict, Gay voluntarily withdrew from all competitions, including the highly anticipated 2013 World Championships in Athletics in Moscow.

On May 2, 2014, the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) announced its sanction against Gay. He received a one-year suspension, retroactively applied from June 23, 2013, the date he tested positive. The potential suspension could have been two years, but it was reduced to one year due to his substantial cooperation with the investigation. As part of the sanction, all of Gay's competitive results from July 15, 2012, until his suspension date were disqualified.

4.2. Medal and Record Stripping

As a direct consequence of his doping violation and the subsequent sanction by USADA, Tyson Gay was stripped of several significant achievements. Most notably, his silver medal from the 4 × 100m relay at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London was revoked. This also resulted in the disqualification of the medals for his relay teammates.

The stripping of his results from July 15, 2012, impacted other competitions as well. While the specific list of all stripped results is extensive, the most prominent was the Olympic relay medal. This action underscores the strict anti-doping policies in track and field, aiming to maintain fair competition and integrity in the sport.

5. Evaluation and Impact

Tyson Gay's career is evaluated through the lens of his extraordinary athletic achievements, his personal character, and the ethical questions raised by his doping case, which had a significant impact on the sport of track and field.

5.1. Sports Community Evaluation

Within the sports community, Tyson Gay was widely regarded for his immense talent, competitive spirit, and humble demeanor. Before his doping revelation, he was seen as a formidable rival to Usain Bolt and Asafa Powell, often pushing the boundaries of sprint times. His triple gold performance at the 2007 World Championships solidified his status as one of the sport's greats. Peers and commentators often praised his dedication to improving his technique, particularly his start, which he worked on with coach Jon Drummond.

Even after his doping admission, Gay's character was often described as humble and respectful of his competitors. The Japanese source notes his acceptance of defeat and praise for Usain Bolt after the 2009 World Championships, which further endeared him to fans. However, his doping violation undeniably tarnished his reputation, leading to a re-evaluation of his achievements and a sense of disappointment among many in the track and field community. Despite this, his athletic prowess, particularly his powerful closing speed and high leg turnover rate, remains a subject of admiration and analysis.

5.2. Impact on Sports Ethics and Fairness

Tyson Gay's doping case had a profound impact on discussions surrounding anti-doping measures and the challenges of maintaining fair competition. Coming after high-profile doping scandals involving athletes like Marion Jones and Justin Gatlin, Gay's positive test further eroded public trust in sprinting. The United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) had even recruited Gay for "Project Believe," an extensive drug testing program aimed at demonstrating that clean athletes could succeed at the highest level. His violation, therefore, was a significant blow to these efforts.

The case highlighted the complexities of anti-doping enforcement, particularly when athletes cooperate with investigations. Gay's reduced ban, from two years to one, was a direct result of his cooperation, raising questions about the balance between punishment and incentivizing information sharing. His case contributed to ongoing debates about the effectiveness of anti-doping measures, the ethical responsibilities of athletes, and the constant battle to ensure a level playing field in professional sports. It served as a stark reminder of the pervasive nature of doping and the continuous need for vigilance and robust testing protocols to protect the integrity of athletic competition.

5.3. Legacy

Tyson Gay's legacy in sprinting is complex, encompassing both his undeniable athletic prowess and the indelible mark of his doping controversy. He will be remembered as an exceptionally talented sprinter, holding the American record in the 100m and achieving a historic triple gold at the 2007 World Championships. His ability to run sub-10s, sub-20s, and sub-45s in the 100m, 200m, and 400m, respectively, makes him a unique figure in sprint history. His races against Usain Bolt and Asafa Powell were highlights of the sport, characterized by intense competition and record-breaking times.

However, his doping violation and the subsequent stripping of medals, including an Olympic silver, cast a long shadow over his achievements. This aspect of his career serves as a cautionary tale, emphasizing the severe consequences of performance-enhancing drug use and its impact on an athlete's historical record and public perception. Despite the controversy, Gay's athletic talent and contributions to the sport's competitive landscape are undeniable. His career offers lessons on the pressures faced by elite athletes and the ongoing struggle for integrity in sports, leaving a dual legacy of remarkable speed and ethical challenges.

6. Awards and Honors

Tyson Gay received numerous accolades and recognitions throughout his career for his outstanding performances in track and field.

- IAAF World Athlete of the Year (Men): 2007

- Men's Track & Field Athlete of the Year: 2007

- ESPY Award for Best Track and Field Athlete: 2008, 2011

- Jesse Owens Award: 2007, 2008

- USOC Sportsman of the Year: 2007

- Men's season's best performance, 100 meters: 2010 (tied with Nesta Carter)

- Men's season's best performance, 200 meters: 2007

Gay also holds several national titles:

- U.S. Championships 100m: 2006, 2007, 2008, 2015 (2013 title stripped)

- U.S. Championships 200m: 2007 (2013 title stripped)

- NCAA Division I Championships 100m: 2004

- NCAA Division I Championships 4 × 100m relay: 2005

- NJCAA Division I Championships 100m: 2002

- NJCAA Division I Indoor Championships 60m: 2002

- NJCAA Division I Indoor Championships 200m: 2002

His overall circuit wins include:

- IAAF Diamond League Overall winner: 2010 (100m)

- 2010 Diamond League: 100m (Gateshead, Stockholm, London, Brussels), 200m (Monaco), 4 × 100m relay (Zürich)

- 2012 Diamond League: 100m (New York, Paris, London)

- 2015 Diamond League: 100m (Eugene, New York), 4 × 100m relay (Monaco)

- 2006 Golden League: 200m (Brussels)

- 2009 Golden League: 100m (Rome)

| Representing the United States and the Americas (Continental Cup only) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Competition | Venue | Rank | Event | Time | Notes |

| 2002 | NACAC U-25 Championships | San Antonio, Texas, U.S. | gold | 4 × 100m relay | 39.79 s | |

| 2005 | World Championships | Helsinki, Finland | 4th | 200m | 20.34 s | |

| DNF (semis) | 4 × 100m relay | - | ||||

| World Athletics Final | Monte Carlo, Monaco | gold | 200m | 19.96 s | ||

| 2006 | World Athletics Final | Stuttgart, Germany | bronze | 100m | 9.92 s | |

| gold | 200m | 19.68 s | ||||

| World Cup | Athens, Greece | gold | 100m | 9.88 s | ||

| gold | 4 × 100m relay | 37.59 s | ||||

| 2007 | World Championships | Osaka, Japan | gold | 100m | 9.85 s | |

| gold | 200m | 19.76 s | ||||

| gold | 4 × 100m relay | 37.78 s | ||||

| 2008 | Olympic Games | Beijing, China | 9th (semis) | 100m | 10.05 s | |

| DNF (semis) | 4 × 100m relay | - | ||||

| 2009 | World Championships | Berlin, Germany | silver | 100m | 9.71 s | American record |

| DNS | 200m | - | ||||

| World Athletics Final | Thessaloniki, Greece | gold | 100m | 9.88 s | ||

| 2010 | Continental Cup | Split, Croatia | gold | 4 × 100m relay | 38.25 s | |

| 2010 | Diamond League Final | Brussels, Belgium | gold | 100m | 9.79 s | |

| 2012 | Olympic Games | London, United Kingdom | DQ | 100m | Doping | |

| DQ | 4 × 100m relay | Doping | ||||

| 2014 | Diamond League Final | Brussels, Belgium | 6th | 100m | 10.01 s | |

| 2015 | World Relays | Nassau, Bahamas | gold | 4 × 100m relay | 37.38 s | American record |

| World Championships | Beijing, China | 6th | 100m | 10 s | ||

| DQ | 4 × 100m relay | - | Out of zone pass | |||

| 2016 | Olympic Games | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | DQ | 4 × 100m relay | - | Out of zone pass |