1. Early Life and Background

Tokhtamysh's early life was marked by familial conflict and a struggle for survival against powerful relatives, which ultimately shaped his path to power.

1.1. Ancestry and Family Origins

Tokhtamysh belonged to the prestigious House of Borjigin, tracing his ancestry directly to Genghis Khan through his eldest son, Jochi. According to detailed genealogies found in historical texts such as the Muʿizz al-ansāb and the Tawārīḫ-i guzīdah-i nuṣrat-nāmah, Tokhtamysh was a descendant of Tuqa-Timur, who was the thirteenth son of Jochi. His specific lineage is recorded as Tūqtāmīsh, son of Tuy-Khwāja, son of Qutluq-Khwāja, son of Kuyunchak, son of Sārīcha, son of Ūrung-Tīmūr, son of Tūqā-Tīmūr, son of Jūjī. Historical sources also note that his mother was Kutan-Kunchek of the Khongirad tribe.

Earlier historical scholarship inaccurately depicted Tokhtamysh, and by extension, Urus Khan, as descendants of Jochi's son Orda. This view has since been corrected; Tokhtamysh and Urus Khan were in fact fourth cousins, belonging to different lines descended from Tuqa-Timur, not Orda. Tuqa-Timur's descendants had been granted territories in the eastern parts of the Kipchak Steppe (modern-day Kazakhstan), part of the Ulus of Orda within the Golden Horde.

1.2. Conflict with Urus Khan and Exile

Tokhtamysh's father, Tuy Khwāja, served as the local ruler of the Mangyshlak Peninsula. He fell into conflict with his cousin and suzerain, Urus Khan, who was the khan of the former Ulus of Orda, centered around Sighnaq. Urus Khan, aiming to consolidate his authority over the fragmented Golden Horde, ordered Tuy Khwāja's execution when he refused to join a campaign against Sarai, the traditional capital. The young Tokhtamysh initially fled but later submitted to Urus Khan and was pardoned due to his youth.

However, Tokhtamysh's ambition did not wane. In 1373, he attempted to establish himself as khan in Sighnaq by gathering opponents of Urus Khan. Urus swiftly moved against him, forcing Tokhtamysh to flee again, only to return, submit, and receive another pardon. In 1375, when Urus seized Sarai, Tokhtamysh seized the opportunity to escape once more. He sought refuge at the court of the powerful Turco-Mongol warlord, Timur (also known as Tamerlane), arriving there in 1376.

With Timur's support, Tokhtamysh established himself at Otrar and Sayram along the Syr Darya in 1376, from where he launched raids into Urus Khan's territory. Urus's son, Qutluq Buqa, attacked and defeated Tokhtamysh, though he himself sustained a fatal wound. Tokhtamysh again fled to Timur, returning with a new army, but suffered another defeat, this time at the hands of Urus's son, Toqtaqiya. Wounded, Tokhtamysh swam across the Syr Darya and once more sought refuge at Timur's court in Bukhara. Urus Khan pursued him, sending envoys to demand Tokhtamysh's extradition, which Timur refused, preparing his forces for confrontation. After a three-month standoff during the winter of 1376-1377, Urus returned home. Upon learning of Urus's death, Timur declared Tokhtamysh the new khan and returned to his capital, Samarkand.

2. Rise to Power and Golden Age

With crucial external backing, Tokhtamysh successfully unified the fragmented Golden Horde, marking a period of renewed strength and influence.

2.1. Reunification of the Golden Horde

Upon Urus Khan's death, his son Toqtaqiya briefly succeeded him, followed by another son, Tīmūr Malik. Tokhtamysh initially faced continued setbacks against Tīmūr Malik, again retreating to Timur's court. Learning of Tīmūr Malik's dissolute rule and the populace's desire for new leadership, Timur dispatched forces to Sawran and Otrar, which surrendered. Advancing on Sighnaq, Timur's forces defeated Tīmūr Malik's army at Qara-Tal, leading to Tīmūr Malik's capture and execution in 1379, betrayed by his own emirs. Tokhtamysh was then installed as khan in Sighnaq, spending the remainder of the year consolidating his authority and gathering resources for his next objective: Sarai.

In 1380, Tokhtamysh advanced westward to take control of Sarai and the central and western parts of the Golden Horde. His growing military might intimidated his former host, Qaghan Beg of the Shiban Ulus, and the reigning khan, ʿArab Shāh, both of whom submitted to Tokhtamysh. Now established as khan at Sarai, Tokhtamysh crossed the Volga to confront and eliminate Mamai, the powerful beglerbeg who controlled the westernmost parts of the Golden Horde. Mamai had been weakened by his recent defeat against the Russians at the Battle of Kulikovo and the death of his puppet khan, Tūlāk. Tokhtamysh decisively defeated Mamai in the Battle of the Kalka River in the autumn of 1381, after successfully persuading several of Mamai's emirs to defect. Mamai fled to the Crimea, but Tokhtamysh's agents pursued and eliminated him in late 1380 or early 1381.

From being a fugitive, Tokhtamysh rapidly transformed into a powerful monarch, becoming the first khan in over two decades to effectively rule both halves (wings) of the Golden Horde. He mastered the left (eastern) wing, the former Ulus of Orda (referred to as White Horde in some Persian sources and Blue Horde in Turkic ones), and then the right (western) wing, the Ulus of Batu (called Blue Horde in some Persian sources and White Horde in Turkic ones). This reunification promised to restore the former greatness of the Golden Horde after a prolonged period of division and internecine conflict. Tokhtamysh wisely and temperately solidified his authority. As early as 1381, he established peace with the Genoese in the Crimea, securing a consistent income. He also ensured the cooperation of emirs and tribal chieftains by confirming their previously granted privileges.

2.2. Campaign against Moscow and Russian Principalities

Encouraged by his successes and the growth of his military strength and wealth, Tokhtamysh next turned his attention to the Russian principalities. Although he did not initially seek conflict, Grand Prince Dmitrij Donskoy of Vladimir-Suzdal had recently suffered heavy losses in defeating Mamai at Kulikovo and was reluctant to face another confrontation. While Dmitrij acknowledged Tokhtamysh as the new khan and his suzerain, he sent rich gifts but withheld tribute payments. When Tokhtamysh's envoy, Āq Khwāja, arrived to summon the Russian princes to the khan's court for the confirmation of their investiture diplomas, he encountered such strong hostility from the populace in Nižnij Novgorod that he was forced to turn back.

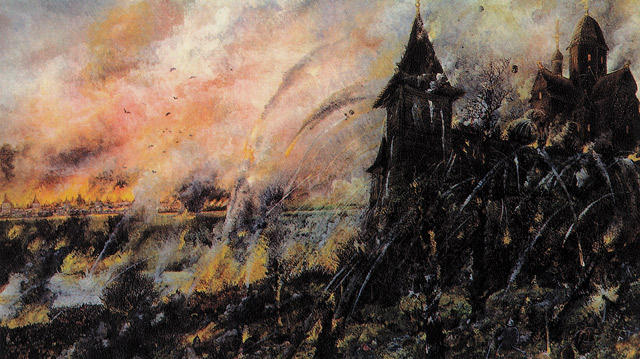

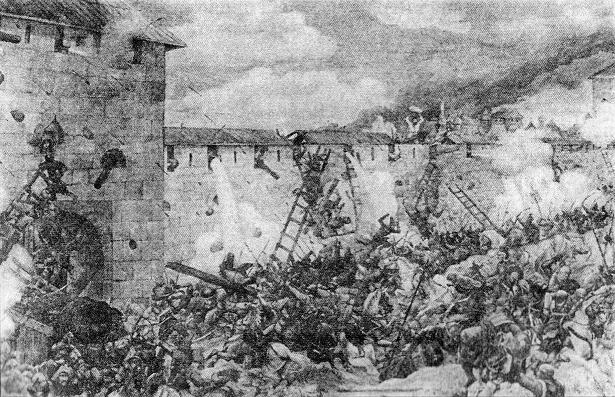

Tokhtamysh prepared for war in 1382, intending to surprise his enemies. He began by ordering the arrest and robbery of Russian merchants on the Volga, confiscating their boats. He then crossed the river with his entire army, attempting a secret advance, though his movements attracted significant attention. Seeking favor with the khan, Grand Prince Oleg Ivanovič of Rjazan' offered his assistance, indicating the fords over the Oka River. Grand Prince Dmitrij Konstantinovič of Nižnij Novgorod also readily submitted and sent his sons, Vasilij and Semën, to serve as guides for Tokhtamysh's campaign. Grand Prince Dmitrij of Moscow, however, refused to submit. He left a strong garrison in his capital under the Lithuanian prince Ostej and sought refuge in Kostroma, hoping to muster larger forces there.

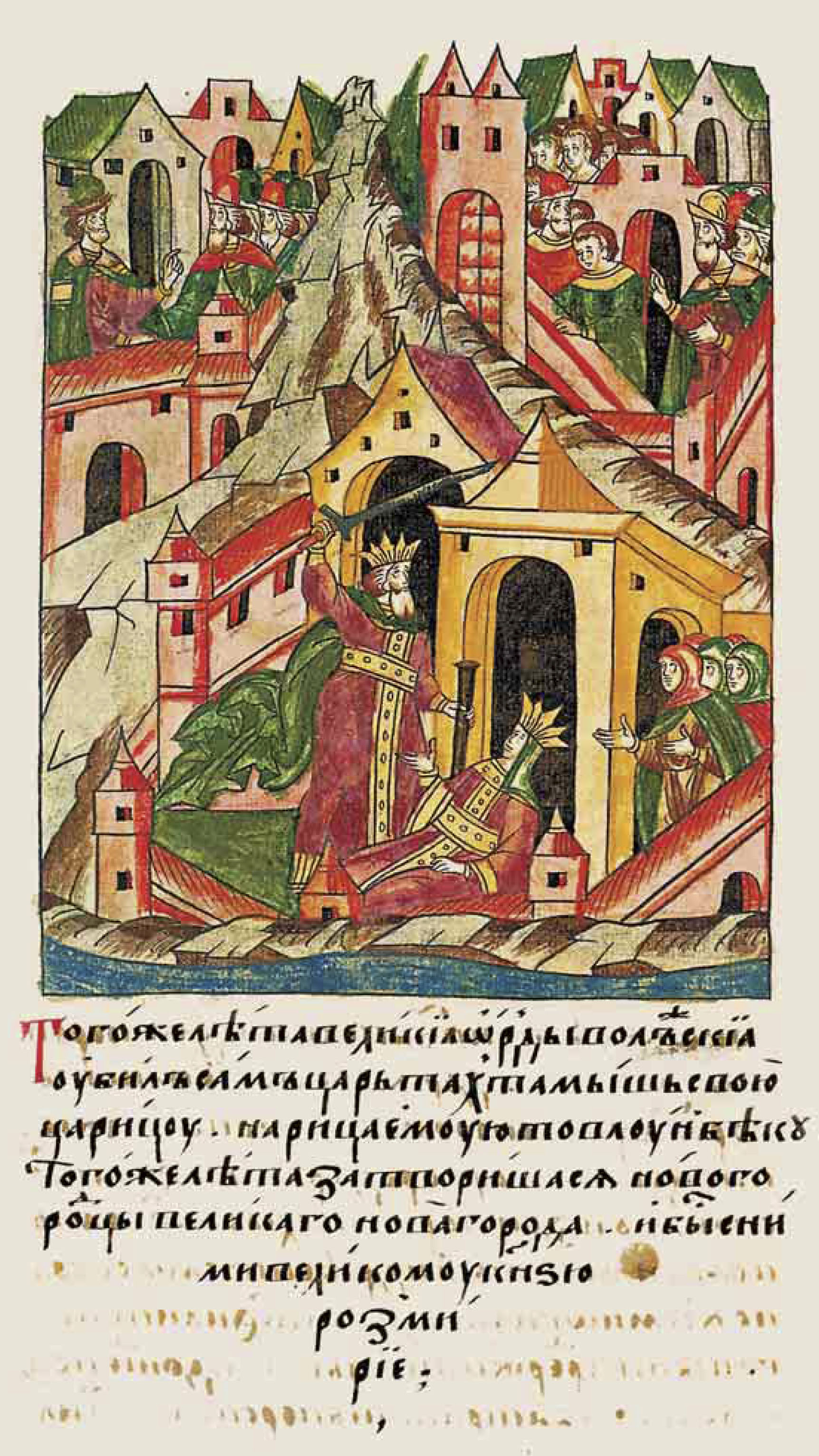

After capturing Serpukhov, Tokhtamysh's forces reached and besieged Moscow on August 23, 1382. Three days later, the citizens were deceived into surrendering by Vasilij and Semën of Nižnij Novgorod. Tokhtamysh's troops stormed into the city, engaging in widespread slaughter and plunder before razing it to the ground as punishment for its ruler's insubordination. Other cities seized by the Mongols during this campaign included Vladimir, Zvenigorod, Jur'ev, Perejaslavl'-Zalesskij, Dmitrov, Kolomna, and Možajsk. On his return journey, Tokhtamysh also sacked Rjazan', despite the cooperation of its prince, demonstrating the harsh realities of Mongol dominance.

Following the submission of the Russian princes and the resumption of their tribute, Tokhtamysh generally adopted more conciliatory policies. Dmitrij of Moscow razed Rjazan' in revenge for Oleg Ivanovič's collaboration, yet faced no punishment from Tokhtamysh. Mihail Aleksandrovič of Tver' was invested as Grand Prince of Vladimir, visiting Tokhtamysh's court with his son Aleksandr, but never fully took possession of the Grand Principality, as Tokhtamysh soon forgave Dmitrij of Moscow. Dmitrij had submitted, surrendering his eldest son Vasilij Dmitrievič as a hostage, and promised to pay tribute, which was duly dispatched in 1383. When Dmitrij Konstantinovič of Nižnij Novgorod died the same year, Tokhtamysh granted that principality to his brother Boris Konstantinovič but gave Suzdal' to Dmitrij's sons, Semën and Vasilij.

In 1386, Dmitrij of Moscow's son Vasilij, who was a hostage at Tokhtamysh's court, escaped to Moldavia and made his way to Moscow via Lithuania. Despite some tension, Moscow faced no adverse consequences. On the contrary, when Dmitrij bequeathed the Grand Principality of Vladimir to his son Vasilij in his will in 1389, Tokhtamysh sanctioned it through his envoy, Shaykh Aḥmad. Semën and Vasilij of Suzdal' expelled their uncle Boris from Nižnij Novgorod, but he sought out Tokhtamysh on campaign and returned with a new investiture from the khan in 1390. Russian recruits subsequently served Tokhtamysh in Central Asia. In 1391, Tokhtamysh dispatched his commander Beg Tut to ravage Vjatka, likely in response to the depredations of the Ushkuyniks, buccaneers along the Volga. However, these buccaneers launched a revenge raid on the area of Bolghar. Seeking cooperation against these and other threats, Tokhtamysh received Vasilij I of Moscow in his camp and invested him with the domain of Nižnij Novgorod, despite the protests of its local princes. Thus, despite his destructive sack of Moscow in 1382, Tokhtamysh ultimately strengthened the power and wealth of Moscow's ruler, inadvertently setting it on a path to annex other Russian and later Mongol polities.

3. Wars with Timur

Tokhtamysh's increasingly aggressive stance against his former patron, Timur, led to devastating wars that would ultimately undo his achievements and critically weaken the Golden Horde.

3.1. Initial Conflicts and Azerbaijan Campaign

In 1383, taking advantage of Timur's preoccupation with affairs in Persia, Tokhtamysh restored the Golden Horde's authority over the semi-autonomous Ṣūfī Dynasty in Khwarazm, seemingly without immediately provoking his former protector. However, under pressure from his emirs to provide profitable campaigns for plunder and perhaps driven by the traditional ambitions of earlier Golden Horde khans, Tokhtamysh led a large force of 5 tumens (approximately 50,000 troops) across the Caucasus during the winter of 1384-1385. He invaded Jalayirid Azerbaijan, capturing its capital, Tabriz, by storm. For ten days, his forces ravaged the neighboring area, withdrawing with substantial plunder, including some 200,000 slaves. Among these captives were thousands of Armenians from the districts of Parskahayk, Syunik, and Artsakh.

Timur, either to exploit Jalayirid weakness or to preempt the Golden Horde's expansion into the region, proceeded to conquer Azerbaijan in 1386. While he was wintering in nearby Karabakh in 1386-1387, Tokhtamysh crossed the mountains in the spring of 1387 and advanced directly towards him. Despite being caught by surprise and nearly defeated, Timur's commanders rallied and successfully repelled Tokhtamysh's attack with timely reinforcements led by Timur's son, Mīrān Shāh. Timur displayed remarkable leniency towards the captured warriors of Tokhtamysh, providing them with food and clothing and allowing them to return home. The motivation for this gesture-whether it was a sign of respect for a royal descendant of Genghis Khan or an attempt to de-escalate an unnecessary conflict on an unwanted front-remains unclear.

Despite his defeat and a subsequent message aimed at diffusing hostilities, Tokhtamysh continued to provoke Timur. While Timur remained in Persia during the winter of 1387-1388, Tokhtamysh overran Central Asia. Part of his forces besieged Sawran, while another crossed Khwarazm to besiege Bukhara. Timur's commanders prepared to defend Samarkand and other towns against Tokhtamysh's expected continued advance, prompting Timur himself to return from Shiraz to Samarkand in February 1388. Upon learning of Timur's movements, Tokhtamysh's forces retreated. Timur became convinced that a serious contest with Tokhtamysh was inevitable. He responded by overthrowing the Ṣūfī Dynasty of Khwarazm for its collusion with Tokhtamysh and razed its capital, (old) Gurgānj, to the ground in 1388.

Increasingly aware that he was outmatched by Timur's growing power, Tokhtamysh sought to forge an anti-Timurid coalition, reaching out to neighboring rulers, including the Mamluk Sultan Barqūq, who were also concerned by Timur's ambitions. Tokhtamysh attempted to take Sawran again in 1388, but was driven off by Timur in snowy January 1389. He launched another attack on Sawran later that year, which also failed, but his forces pillaged the surrounding area and plundered the town of Yasī (now Turkistan) before retreating to safety when Timur defeated Tokhtamysh's vanguard and crossed the Syr Darya in pursuit. Timur then seized Sighnaq but soon diverted his attention to Tokhtamysh's allies further east.

3.2. First Timurid Invasion (Battle of Kondurcha)

Determined to take the initiative and strike decisively into Tokhtamysh's core territories, Timur gathered a large army and set out in February 1391 from Tashkent. He ignored Tokhtamysh's envoys seeking peace and advanced into the territories of the former Ulus of Orda. For four months of travel and hunting, Timur failed to catch Tokhtamysh, who seemed to be retreating northward. Only after reaching the headwaters of the Tobol did Timur discover that Tokhtamysh was regrouping to the west, across the Ural, planning to defend the crossing. Timur advanced on the Ural and crossed it further upstream, forcing Tokhtamysh to retreat towards the Volga, where he hoped for reinforcements from the Crimea, Bolghar, and even Russia.

To preempt these reinforcements, Timur finally caught up with Tokhtamysh and forced him to engage in the Battle of the Kondurcha River on June 18, 1391. The hard-fought battle resulted in the complete rout of Tokhtamysh's forces and his flight from the battlefield. Many of his soldiers, trapped between Timur's army and the Volga, were either captured or slaughtered. Timur and his victorious army celebrated their triumph for over a month on the banks of the Volga. Surprisingly, Timur did not attempt to consolidate his control over the area before returning home.

At their request, Timur left behind two princes descended from Tuqa-Timur: Tīmūr Qutluq (son of Qutluq Tīmūr) and Kunche Oghlan (Tīmūr Qutluq's paternal uncle), along with the Manghit emir Edigu (Tīmūr Qutluq's maternal uncle). While this act is sometimes interpreted as Timur's investiture of Tīmūr Qutluq as khan, it is more likely that the three were tasked with recruiting additional troops for the Timurid army. Only Kunche Oghlan remained loyal to his vow, returning to Timur with his recruits before deserting Tokhtamysh the following year. Meanwhile, Tīmūr Qutluq and Edigu began to operate independently with a growing following and appear to have declared Tīmūr Qutluq khan in the left (eastern) wing of the Golden Horde. Concurrently, one of Tokhtamysh's commanders, Beg Pūlād (possibly a grandson of Urus Khan), who had escaped the Battle of Kondurcha, declared himself khan at Sarai, presuming Tokhtamysh had perished.

Despite these challenges, Tokhtamysh had survived and still commanded enough authority and manpower to strike back. He defeated and expelled Beg Pūlād from Sarai, chasing him into the Crimea, and, after besieging him in Solkhat, ultimately killed him. Another potential challenger in the Crimea, Tokhtamysh's second cousin Tāsh Tīmūr, temporarily recognized Tokhtamysh's rule but maintained some autonomy. Tokhtamysh dealt similarly with Edigu, reaching terms with him in exchange for his submission, leaving him with autonomous authority in the east and significantly weakening Tīmūr Qutluq's position. Tokhtamysh felt powerful enough to demand tribute from the Polish King Władysław II Jagiełło in 1393 for lands that his father, Grand Duke Algirdas of Lithuania, had taken from the Golden Horde in the past, and his demands were met.

Tokhtamysh once again sought to form an anti-Timurid coalition, reaching out to the Mamluk Sultan Barqūq, the Ottoman Sultan Bayezit I, and the Georgian King Giorgi VII. Timur retaliated by invading Georgia. Although Tokhtamysh seemed to have internal troubles with his own emirs in the summer of 1394, that autumn he was able to raid across the Caucasus into Shirvan. However, the approach of Timur's forces prompted an immediate retreat.

3.3. Second Timurid Invasion (Battle of the Terek River)

Timur now determined that a second, decisive campaign into the Golden Horde was necessary. After a period of diplomatic maneuvering by both sides, Timur set out with a large army towards Derbent in March 1395. After crossing the pass, Timur's army ravaged the area up to the Terek River, where it encountered Tokhtamysh's forces. After Timur's troops destroyed Tokhtamysh's vanguard, the main battle took place on April 15-16, 1395. Like the Battle of Kondurcha four years earlier, it was a hard-fought engagement between forces of nearly equal strength. Although Timur, who fought like a common warrior, was nearly captured or killed, he once again emerged victorious, following a period of dissension among Tokhtamysh's emirs. Tokhtamysh fled north to Bolghar and later possibly to Moldavia.

Part of Timur's forces gave chase, catching up with some of the enemy by the Volga and driving them into the river. Timur's local allies, led by the Jochid prince Quyurchuq, a son of Urus Khan, advanced on the opposite, left bank of the Volga to take over the area. Timur then probed northward as far as Yelets, before turning to widespread ravaging of the Golden Horde's cities. At Tana, he initially welcomed rich gifts from Italian merchants but then enslaved all Christians and destroyed their facilities. Passing through Circassia, he proceeded to pillage and destroy cities along the Volga, from (old) Astrakhan to Sarai, and to Gülistan, during the winter of 1395-1396. The surviving inhabitants were enslaved and "driven like sheep." Timur departed for Samarkand via Derbent in the spring of 1396, laden with plunder and accompanied by herds and captives, including merchants, artists, and craftsmen, leaving the Golden Horde economically exhausted and utterly pillaged. This campaign inflicted a severe and lasting blow to the Golden Horde's infrastructure, trade, and overall stability.

4. Later Life and Downfall

After his crushing defeats by Timur, Tokhtamysh's life became a desperate struggle to regain his lost throne, leading to alliances and further battles that ultimately sealed his fate.

4.1. Exile and Final Efforts

Tokhtamysh survived Timur's devastating onslaughts, but his position was far more precarious than before. The ruined capital, Sarai, fell into the hands of Timur's protégé, Quyurchuq, while the area of Astrakhan and the eastern parts of the Golden Horde came under the control of Tīmūr Qutluq and Edigu, who had reunited their forces. They soon expelled or eliminated Quyurchuq, taking over Sarai in 1396 or 1397, but placated Timur by sending an embassy in 1398 to assure him of their submission.

Meanwhile, Tokhtamysh set about reasserting his authority in the southwestern parts of the Golden Horde, killing his cousin Tāsh Tīmūr, who had declared himself khan in the Crimea. He also engaged in conflict with the Genoese there, besieging Kaffa in 1397. In late 1397 or early 1398, Tokhtamysh briefly triumphed over his rivals, taking over Sarai and the Volga towns, sending out triumphant missives through his envoys. However, his success was short-lived: Tokhtamysh was defeated in battle by Tīmūr Qutluq and fled, first to the Crimea, where he was met with hostility, and then via Kiev to Vytautas, the Grand Prince of Lithuania.

Vytautas settled Tokhtamysh and his followers near Vilnius and Trakai, though many of Tokhtamysh's supporters eventually abandoned him, making their way to the Balkans to serve the Ottoman Sultan Bayezit I. Tokhtamysh and Vytautas signed a treaty in which Tokhtamysh confirmed Vytautas as the rightful ruler of Ruthenian lands that had once been part of the Golden Horde but now belonged to Lithuania. In return for military assistance to recover his throne, Tokhtamysh promised Vytautas the tribute from the Russian principalities. It is possible the treaty also stipulated that Vytautas would pay tribute from these Ruthenian lands once Tokhtamysh regained his throne. Vytautas may have harbored ambitions of establishing himself as an overlord in the lands of the Golden Horde.

Tīmūr Qutluq sent an envoy to demand Tokhtamysh's extradition from Lithuania, but Vytautas responded defiantly: "I will not give up Tsar Tokhtamysh, but wish to meet Tsar Temir-Kutlu in person." Vytautas and Tokhtamysh prepared their combined Lithuanian and Mongol forces for a joint campaign, supported by Polish volunteers under Spytek of Melsztyn. In the summer of 1399, Vytautas and Tokhtamysh set out against Tīmūr Qutluq and Edigu with a large army. On the Vorskla River, they encountered Tīmūr Qutluq's forces, who initiated negotiations, intending to delay the engagement until Edigu could arrive with reinforcements. Tīmūr Qutluq feigned agreement to submit to Vytautas and pay him annual tribute but requested a three-day delay to consider further demands. This delay was sufficient for Edigu to arrive with his reinforcements. Edigu then met with the Lithuanian ruler, separated by the river. After further negotiations proved fruitless, the two forces engaged in the Battle of the Vorskla River on August 12, 1399. Using a feigned retreat tactic, Tīmūr Qutluq and Edigu successfully enveloped the forces of Vytautas and Tokhtamysh, inflicting a severe defeat upon them. Tokhtamysh fled the battlefield and made his way east to Sibir; Vytautas survived the battle, though some twenty princes, including two of his cousins, perished in the fight. This defeat was disastrous, effectively ending Vytautas' ambitious policy in the Pontic steppes.

4.2. Death

Reduced to the status of a wandering adventurer, Tokhtamysh traversed the territories of the Golden Horde, eventually reaching its peripheral Siberian possessions. By 1400, he managed to bring parts of this remote area under his control, and by 1405, he was attempting to ingratiate himself with Timur, his former protector turned formidable enemy, who had recently quarreled with Edigu. However, Timur's death in February 1405 rendered any reconciliation moot.

Throughout this period, Tokhtamysh naturally attracted the persistent hostility of Edigu and his new puppet khan, Shādī Beg. It is said that Edigu fought Tokhtamysh on sixteen separate occasions between 1400 and 1406. In their final confrontation, after suffering a reverse at Tokhtamysh's hands, Edigu cunningly spread a rumor about his own death. This ruse drew Tokhtamysh out into the open, where he was ambushed and killed in a hail of darts and spears in late 1406, near Tyumen. While Khan Shādī Beg reportedly claimed or was given credit for Tokhtamysh's death, other accounts attribute it to Edigu or Edigu's son, Nūr ad-Dīn. Russian chroniclers recorded his death in 1406: Тое же зимы царь Женибек уби Тактамыша в Сибирскои земли близ Тюмени, а сам седе на Орде.Russian (That same winter, tsar Shadi Beg killed Tokhtamysh in the Siberian lands near Tyumen, and he himself sat on [the throne of] the Horde.) This account is from the Arkhangelsk Chronicle.

5. Assessment and Legacy

Tokhtamysh's reign represents a pivotal, yet ultimately tragic, chapter in the history of the Golden Horde, marked by both remarkable achievements and catastrophic miscalculations that irrevocably altered its destiny.

5.1. Achievements and Positive Impact

When he reunified the Golden Horde in 1380-1381, Tokhtamysh showed great promise in revitalizing and stabilizing the polity after two decades of chronic civil war. His success in bringing both the Blue and White Hordes under a single rule was a significant accomplishment, temporarily restoring the unity that had been lost. His decisive sack of Moscow in 1382 successfully reversed the setback suffered by the Golden Horde at the Battle of Kulikovo two years prior, reasserting Mongol dominance over the Russian principalities and ensuring the recommencement of tribute payments. This act temporarily restored the Horde's prestige and demonstrated its enduring military might. Furthermore, his invasion of Azerbaijan in 1385 followed the long-standing aspirations of earlier khans to exploit or conquer that wealthy region. By 1385, Tokhtamysh was at the zenith of his power, and the future of the Golden Horde appeared promising under his unified rule. He was also the last Khan of the Golden Horde to mint coins with Mongolian script, symbolizing a brief return to traditional Mongol authority.

5.2. Limitations and Criticism

Despite his initial successes, Tokhtamysh's reign was ultimately defined by his fatal decision to engage in and escalate conflict with his former protector, Timur. This overambitious and destructive rivalry set a course that swiftly undid all of Tokhtamysh's achievements and led directly to his own destruction and, more significantly, the catastrophic weakening of the Golden Horde. His repeated provocations of Timur, driven by a desire for plunder and perhaps a misjudgment of his own strength, led to two devastating Timurid invasions into the Golden Horde's core territories in 1391 and 1395-1396.

These invasions inflicted irreversible damage. Timur's systematic destruction and pillaging of the Golden Horde's main urban centers, such as Sarai, Astrakhan, Gülistan, and the Italian colony of Tana, dealt a severe and lasting blow to the polity's trade-based economy. The mass enslavement of inhabitants, including skilled artisans and merchants, further crippled the Horde's human capital and economic prospects. This profound economic and social devastation significantly undermined the Golden Horde's ability to recover and maintain its power, contributing directly to its eventual disintegration.

Furthermore, Tokhtamysh's search for allies after weakening Moscow inadvertently strengthened his rivals. By conceding the Grand Principality of Vladimir as a hereditary possession of the Prince of Moscow in 1389 and allowing Moscow to take over Nižnij Novgorod in 1393, he fostered the growth of a future adversary. Similarly, his alliance with Lithuania established a dangerous precedent, allowing the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to become involved in the internal politics of the Golden Horde, influencing and even facilitating the rise and fall of khans for decades to come, including several of Tokhtamysh's own sons. Neither of these alliances saved Tokhtamysh, whose authority was shattered by Timur's invasions, driving him into continuous competition with rival khans until his death in Sibir in 1406. The relative consolidation of the khan's authority that Tokhtamysh achieved survived him only briefly, largely due to the influence of his nemesis, Edigu. However, after 1411, it gave way to another prolonged period of civil war that irrevocably led to the final disintegration of the Golden Horde. Tokhtamysh's actions, while initially aimed at restoring a powerful empire, ultimately catalyzed its downfall, demonstrating how personal ambition and miscalculated foreign policy can have devastating and long-lasting consequences for entire societies.

6. Family

Tokhtamysh had a complex family life, with notable spouses and many children who would go on to play significant roles in the tumultuous history of the Golden Horde. Among his marriages, Tokhtamysh notably married the widow of Mamai, who is likely identical to a daughter of Berdi Beg and to Tulun Beg Khanum, who had briefly ruled at Sarai in 1370-1371. In 1386, Tokhtamysh had her executed, apparently for her alleged involvement in an obscure conspiracy.

According to the Muʿizz al-ansāb, Tokhtamysh had eight sons and five daughters, as well as six grandchildren. His notable children include:

- Jalāl ad-Dīn (1380-1412), born to Ṭaghāy-Bīka. He served as Khan of the Golden Horde from 1411 to 1412.

- Abū-Saʿīd

- Amān Beg

- Karīm Berdi, who became Khan of the Golden Horde in 1409, 1412-1413, and 1414, and died around 1417.

- Sayyid Aḥmad, possibly Khan of the Golden Horde from 1416 to 1417. (He is distinct from Sayyid Aḥmad, who reigned as Khan from 1432 to 1459).

- Kebek, who ruled as Khan of the Golden Horde from 1413 to 1414.

- Chaghatāy-Sulṭān

- Sarāy-Mulk

- Shīrīn-Bīka

- Jabbār Berdi, who served as Khan of the Golden Horde from 1414 to 1415 and again from 1416 to 1417.

- Qādir Berdi, born to a Circassian concubine, who was Khan of the Golden Horde in 1419.

- Abū-Saʿīd

- Iskandar, born to Ūrun-Bikā.

- Kūchuk Muḥammad, also born to Ūrun-Bikā. (He is distinct from Küchük Muḥammad, who reigned as Khan from 1434 to 1459).

- Malika, born to Ṭaghāy-Bīka.

- Jānika, born to Ṭaghāy-Bīka, who married Edigu.

- Saʿīd-Bīka, born to Ṭaghāy-Bīka.

- Bakhtī-Bīka, born to Shukr-Bīka-Āghā.

- Mayram-Bīka, born to Ūrun-Bikā.

7. Genealogy

Tokhtamysh's lineage traces back to Genghis Khan through his son Jochi and the latter's thirteenth son, Tuqa-Timur, placing him within a significant branch of the Borjigin dynasty. His ancestry is as follows:

- Genghis Khan

- Jochi

- Tuqa-Timur

- Urung-Timur

- Saricha

- Kuyunchak

- Qutluq Khwaja

- Tuy Khwaja

- Tokhtamysh

- Jalāl ad-Dīn

- Karīm Berdi

- Kebek

- Jabbār Berdi

- Qādir Berdi

- Abū-Saʿīd

- Iskandar

- Kūchuk Muḥammad

- Tokhtamysh

- Tuy Khwaja

- Qutluq Khwaja

- Kuyunchak

- Saricha

- Urung-Timur

- Tuqa-Timur

- Jochi