1. Overview

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 - March 13, 1906) was a pioneering American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family deeply committed to social equality, Anthony began her activism early, collecting anti-slavery petitions at just 17 years old. Her lifelong dedication to justice and democratic participation for women and marginalized groups became the hallmark of her career.

Anthony's influence extended across various social reform movements. She co-founded the New York Women's State Temperance Society in 1852, advocating for temperance and women's rights. During the American Civil War, she and Elizabeth Cady Stanton established the Women's Loyal National League, which conducted the largest petition drive in U.S. history at the time, gathering nearly 400,000 signatures in support of abolishing slavery. After the war, they initiated the American Equal Rights Association to campaign for equal rights for both women and African Americans.

A key figure in the women's rights movement, Anthony co-founded the weekly newspaper The Revolution in 1868, a platform for women's suffrage and broader social reforms. In 1869, she and Stanton established the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which later merged with a rival organization to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890, with Anthony becoming its effective leader. She traveled extensively, delivering 75 to 100 speeches annually, tirelessly campaigning for women's voting rights across numerous states and lobbying Congress.

In 1872, Anthony was famously arrested in her hometown of Rochester, New York, for voting in violation of laws that restricted suffrage to men. Her subsequent trial, though resulting in a conviction, brought national attention to the cause. In 1878, she and Stanton introduced a constitutional amendment for women's suffrage, colloquially known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which was eventually ratified as the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Beyond national efforts, Anthony also worked internationally, playing a key role in founding the International Council of Women and the International Alliance of Women, fostering global cooperation for women's rights.

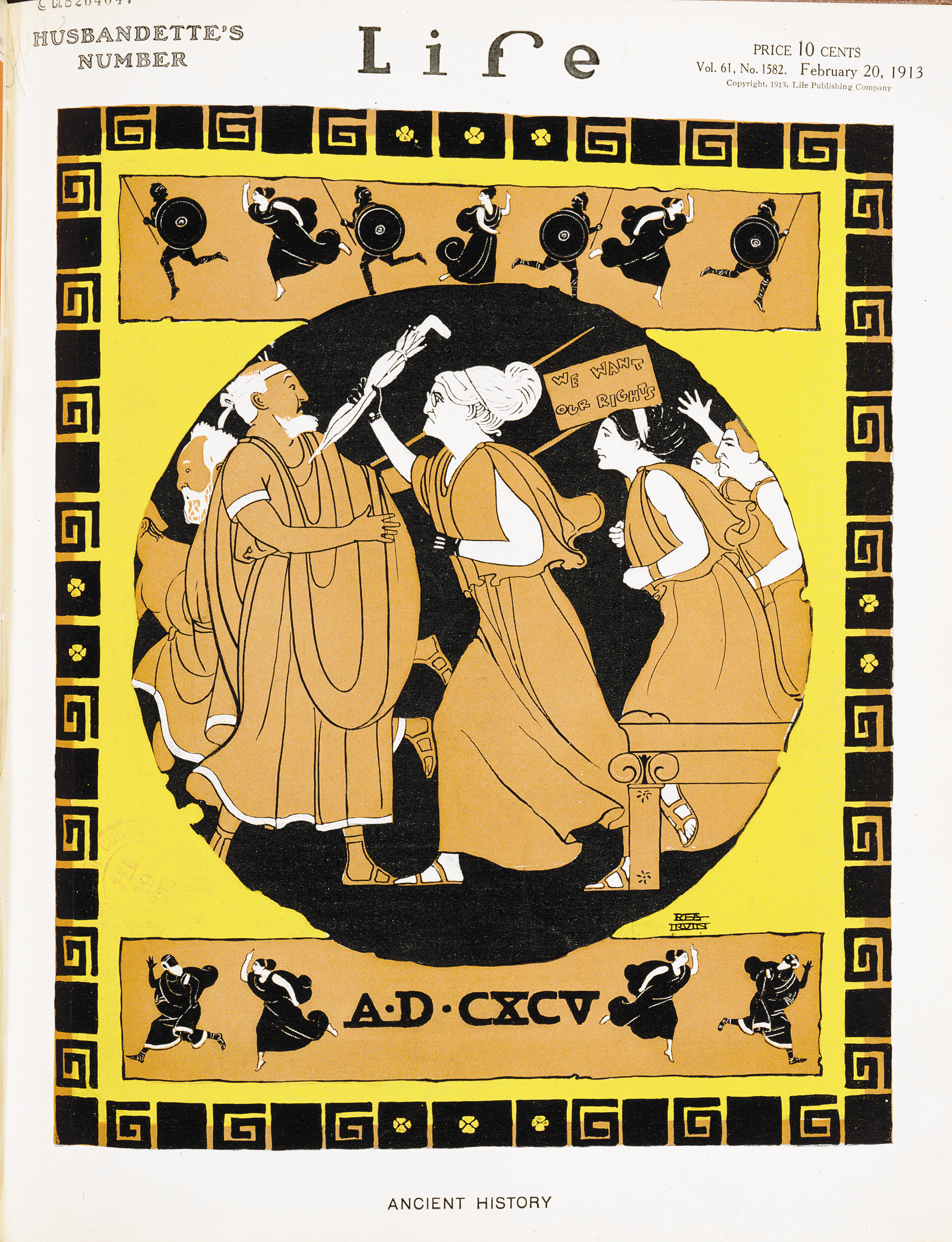

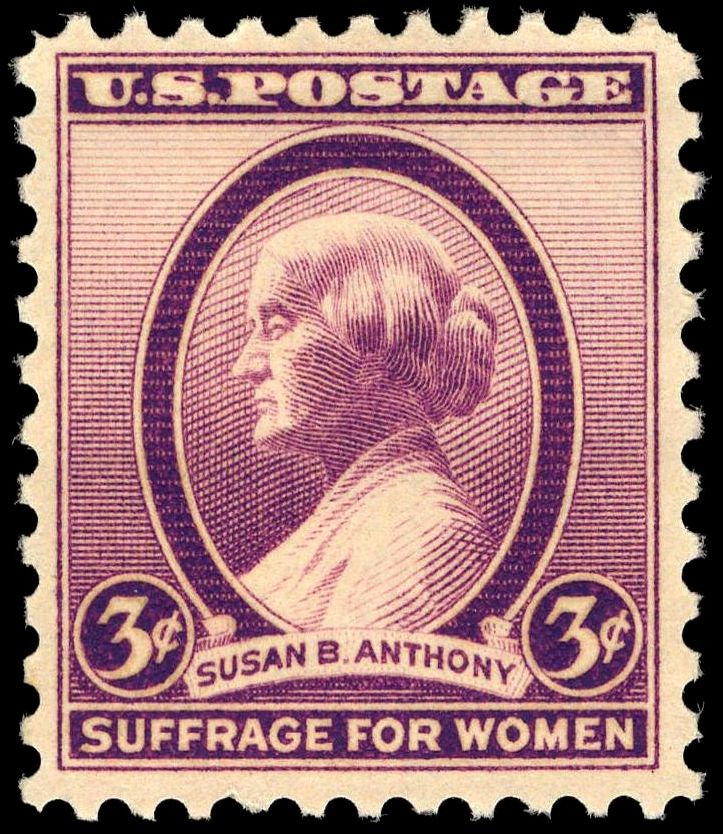

Initially met with ridicule and accusations of undermining marriage, public perception of Anthony shifted dramatically during her lifetime. Her 80th birthday was celebrated at the White House at the invitation of President William McKinley. She became the first female citizen to be depicted on U.S. coinage, appearing on the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin in 1979. Anthony's unwavering commitment and strategic leadership solidified her legacy as a pivotal force in the fight for gender equality and democratic participation in the United States and worldwide.

2. Early Life and Background

Susan Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, in Adams, Massachusetts, as the second oldest of seven children to Daniel Anthony and Lucy Read Anthony. She was named after her maternal grandmother, Susanah, and her father's sister, Susan. In her youth, she adopted "B." as her middle initial, inspired by her namesake Aunt Susan, who had married a man named Brownell, though Anthony herself never used the name Brownell and disliked it.

Her family was deeply passionate about social reform. Her brothers, Daniel and Merritt, moved to Kansas to support the anti-slavery movement there, with Merritt even fighting alongside John Brown during the Bleeding Kansas crisis. Daniel later became a newspaper owner and mayor of Leavenworth. Anthony's sister, Mary, with whom she later shared a home, became a public school principal in Rochester and a women's rights activist.

Anthony's father was a dedicated abolitionist and temperance advocate. As a Quaker, he had a complex relationship with his traditionalist congregation, which rebuked him for marrying a non-Quaker and later disowned him for allowing a dance school in his home. Despite this, he continued to attend Quaker meetings and became more radical in his beliefs. Anthony's mother, a Baptist, helped raise their children in a more tolerant version of her husband's religious tradition. Their father encouraged all his children, both girls and boys, to be self-supporting, teaching them business principles and giving them responsibilities at an early age.

When Anthony was six, her family moved to Battenville, New York, where her father managed a large cotton mill, having previously operated his own smaller factory. At 17, Anthony was sent to a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia, where she found the strict and sometimes humiliating atmosphere challenging. Her studies were cut short after one term when her family faced financial ruin during the Panic of 1837. They were forced to sell their possessions at auction, but her maternal uncle intervened, buying most of their belongings and returning them to the family. To help her family financially, Anthony left home to teach at a Quaker boarding school.

In 1845, the family relocated to a farm on the outskirts of Rochester, New York, purchased partly with her mother's inheritance. Here, they became deeply involved in the anti-slavery movement, associating with a group of Quaker social reformers who had left their congregation due to restrictions on reform activities. In 1848, this group formed the Congregational Friends. The Anthony farmstead soon became a regular Sunday afternoon gathering place for local activists, including Frederick Douglass, a former slave and prominent abolitionist who became a lifelong friend of Anthony.

The Anthony family also began attending services at the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, which was known for its association with social reform. The Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848 was held at this church in 1848, inspired by the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, held two weeks prior in a nearby town. Anthony's parents and her sister Mary attended the Rochester convention and signed the Declaration of Sentiments that had been adopted at Seneca Falls.

Anthony herself did not participate in either of these conventions because she had moved to Canajoharie in 1846 to be headmistress of the female department of the Canajoharie Academy. Away from Quaker influences for the first time at age 26, she began to adopt more stylish dresses, replacing her plain clothing, and ceased using traditional Quaker speech forms like "thee." While interested in social reform and distressed by being paid significantly less than men for similar work, she initially found her father's enthusiasm for the Rochester women's rights convention amusing. She later explained, "I wasn't ready to vote, didn't want to vote, but I did want equal pay for equal work."

When the Canajoharie Academy closed in 1849, Anthony returned to Rochester to manage the family farm, allowing her father to focus on his insurance business. Although she worked at this for a couple of years, she found herself increasingly drawn to reform activities. With her parents' support, she soon became fully engaged in reform work, living almost entirely on fees earned as a speaker for the rest of her life.

3. Early Activism and Social Reform

Anthony embarked on her career in social reform with immense energy and determination. She educated herself on various reform issues, finding herself drawn to the more radical ideas of figures like William Lloyd Garrison, George Thompson, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Early in her activism, she adopted the controversial Bloomer dress, which consisted of pantaloons worn under a knee-length dress. Although she found it more practical than the traditional heavy dresses that dragged on the ground, she reluctantly stopped wearing it after a year because it provided her opponents with an easy distraction, allowing them to focus on her attire rather than her ideas.

Anthony's commitment to social justice was evident from a young age. At 16, in 1837, she actively collected petitions against slavery, participating in organized resistance to the newly established "gag rule" that prohibited anti-slavery petitions in the U.S. House of Representatives. This early involvement laid the groundwork for her extensive future work in the abolitionist movement.

In 1860, Susan B. Anthony articulated her belief in radical reform, stating: "Cautious, careful people, always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform. Those who are really in earnest must be willing to be anything or nothing in the world's estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathy with despised and persecuted ideas and their advocates, and bear the consequences."

Her initial forays into public speaking and activism often highlighted the gender discrimination prevalent at the time. Her experiences in the temperance movement, where she was denied the right to speak due to her gender, further fueled her resolve to challenge societal injustices and advocate for women's rights. This early period of activism demonstrated her unwavering commitment to challenging the status quo and fighting for equality across various social issues.

4. Partnership with Elizabeth Cady Stanton

In 1851, Anthony was introduced to Elizabeth Cady Stanton by their mutual acquaintance, Amelia Bloomer, a prominent feminist. Stanton had been one of the key organizers of the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 and had introduced the controversial resolution advocating for women's suffrage. Anthony and Stanton quickly formed a deep friendship and a highly productive working relationship that proved pivotal for both women and for the broader women's movement. Their bond was so strong that after the Stantons moved to New York City in 1861, a dedicated room was set aside for Anthony in every house they lived in. One of Stanton's biographers estimated that Stanton likely spent more time with Anthony over her lifetime than with any other adult, including her own husband.

The two women possessed complementary skills that made their collaboration exceptionally effective. Anthony excelled at organizing, managing, and executing campaigns, while Stanton possessed a remarkable aptitude for intellectual matters, writing, and developing theoretical frameworks. Anthony herself was often dissatisfied with her own writing ability and published relatively little, with most direct quotes attributed to her coming from her speeches, letters, and diary entries.

Given Stanton's responsibilities as a mother of seven children and Anthony's unmarried status and freedom to travel, Anthony frequently assisted Stanton by supervising her children, allowing Stanton the time to write. As one of Anthony's biographers noted, "Susan became one of the family and was almost another mother to Mrs. Stanton's children." A biography of Stanton further describes their early collaboration: "Stanton provided the ideas, rhetoric, and strategy; Anthony delivered the speeches, circulated petitions, and rented the halls. Anthony prodded and Stanton produced."

Their unique dynamic was often humorously acknowledged by those around them. Stanton's husband once remarked, "Susan stirred the puddings, Elizabeth stirred up Susan, and then Susan stirs up the world!" Stanton herself famously encapsulated their partnership by saying, "I forged the thunderbolts, she fired them." By 1854, their collaboration had matured, making the New York State women's movement "the most sophisticated in the country," according to women's history professor Ann D. Gordon.

Despite their close collaboration, their interests diverged somewhat as they aged. Anthony began to form alliances with more conservative groups, such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union, which supported women's suffrage. This often irritated Stanton, who observed, "I get more radical as I get older, while she seems to grow more conservative." This difference became particularly evident in 1895 when Stanton published The Woman's Bible, a controversial work that critiqued the use of the Bible to justify women's inferior status. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) voted to disavow any connection with the book, despite Anthony's strong objection that such a move was unnecessary and hurtful. Even so, Anthony declined to assist with the book's preparation, telling Stanton, "You say 'women must be emancipated from their superstitions before enfranchisement will have any benefit,' and I say just the reverse, that women must be enfranchised before they can be emancipated from their superstitions."

Despite these occasional frictions, their relationship remained deeply close. Upon Stanton's death in 1902, Anthony wrote to a friend, "Oh, this awful hush! It seems impossible that voice is stilled which I have loved to hear for fifty years. Always I have felt I must have Mrs. Stanton's opinion of things before I knew where I stood myself. I am all at sea..." Their partnership endured for over five decades, serving as the intellectual and organizational backbone of the American women's rights movement.

5. Abolitionist Activities

Susan B. Anthony's involvement in the anti-slavery movement was a significant aspect of her early activism, deeply influencing her later work for women's rights. At the young age of 16, in 1837, she began collecting petitions against slavery, demonstrating her early commitment to challenging societal injustices. This was part of an organized resistance against the "gag rule" that prohibited anti-slavery petitions in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In 1851, Anthony played a crucial role in organizing an anti-slavery convention in Rochester, New York. Her dedication extended to direct action, as she was also part of the Underground Railroad, a network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. An entry in her diary from 1861 notes, "Fitted out a fugitive slave for Canada with the help of Harriet Tubman."

In 1856, Anthony accepted the position of New York State agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, with the understanding that she would also continue her advocacy for women's rights. In this role, she organized anti-slavery meetings throughout the state, often under banners proclaiming "No compromise with slaveholders. Immediate and Unconditional Emancipation."

Her fearlessness in the face of opposition became legendary. In 1859, following John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Anthony organized and presided over a meeting of "mourning and indignation" in Rochester's Corinthian Hall on the day of Brown's execution, raising money for his family. However, on the eve of the American Civil War, opposition intensified, and mob actions shut down her meetings across New York in early 1861. In Rochester, police had to escort Anthony and other speakers from the building for their safety. In Syracuse, a local newspaper reported, "Rotten eggs were thrown, benches broken, and knives and pistols gleamed in every direction."

Anthony articulated a vision of a racially integrated society, which was radical for a time when many abolitionists, including figures like Abraham Lincoln, debated the future of freed slaves and even proposed sending African Americans to newly established colonies in Africa. In a 1861 speech, Anthony declared, "Let us open to the colored man all our schools ... Let us admit him into all our mechanic shops, stores, offices, and lucrative business avocations ... let him rent such pew in the church, and occupy such seat in the theatre ... Extend to him all the rights of Citizenship."

The nascent women's rights movement was closely associated with the American Anti-Slavery Society, led by William Lloyd Garrison, and relied heavily on abolitionist resources, including newspaper publications and some funding. However, tensions arose between women's rights leaders and male abolitionists who, while supportive of women's rights, feared that a vigorous campaign for women's suffrage would detract from the anti-slavery cause. In 1860, when Anthony sheltered a woman fleeing an abusive husband, Garrison insisted that the woman give up her child, citing laws that gave husbands complete control over children. Anthony retorted, reminding Garrison of his own defiance of law in helping slaves escape: "Well, the law which gives the father ownership of the children is just as wicked and I'll break it just as quickly."

When Stanton introduced a resolution at the National Woman's Rights Convention in 1860 favoring more lenient divorce laws, leading abolitionist Wendell Phillips not only opposed it but tried to have it removed from the record. Similarly, when Stanton, Anthony, and others supported a bill allowing divorce in cases of desertion or inhuman treatment, Horace Greeley, an abolitionist newspaper publisher, campaigned against it. Despite the valuable help provided by figures like Garrison, Phillips, and Greeley, Anthony concluded that women needed to pursue their own agenda independently. In a letter to Lucy Stone, she stated, "The Men, even the best of them, seem to think the Women's Rights question should be waived for the present. So let us do our own work, and in our own way."

In 1861, Anthony was persuaded to pause preparations for the annual women's rights convention to focus on efforts to win the Civil War, though she remained skeptical of the promise that women's rights would be recognized after the war if they contributed to its end.

6. Temperance Movement Engagement

Anthony's involvement in the temperance movement was an early and formative experience that highlighted the deep connections between social reform and women's rights. At the time, temperance was intrinsically linked to women's rights because existing laws granted husbands complete control over the family and its finances. A woman whose husband was an alcoholic had little legal recourse, even if his drinking led to destitution and abuse towards her and their children. Obtaining a divorce was difficult, and even then, the husband could easily retain sole guardianship of the children.

While teaching in Canajoharie, Anthony joined the Daughters of Temperance, and in 1849, she delivered her first public speech at one of their meetings. Her commitment to the cause deepened, leading her to be elected as a delegate to the state temperance convention in 1852. However, when she attempted to speak, the chairman stopped her, asserting that women delegates were present only to listen and learn.

This direct experience of gender discrimination in a public forum spurred Anthony and other women to walk out immediately. They announced their own meeting, which led to the formation of a committee tasked with organizing a women's state convention. Largely organized by Anthony, this convention, attended by 500 women, met in Rochester in April 1852. It resulted in the creation of the Women's State Temperance Society, with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as president and Anthony as its state agent.

Anthony and her colleagues diligently collected 28,000 signatures on a petition for a law to prohibit the sale of alcohol in New York State. She organized a hearing on this proposed law before the New York legislature, marking the first time a group of women had initiated such a hearing in the state. However, at the organization's convention the following year, conservative members opposed Stanton's advocacy for the right of an alcoholic's wife to obtain a divorce. Stanton was voted out of her presidency, leading both she and Anthony to resign from the organization.

In 1853, Anthony attended the World's Temperance Convention in New York City, which became mired in a three-day chaotic dispute over whether women would be permitted to speak. Years later, Anthony reflected on these experiences, observing, "No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized." Following this period, Anthony increasingly focused her energy on abolitionist and women's rights activities, recognizing the fundamental need for women to have a public voice and legal standing.

7. Women's Rights Movement Leadership

Susan B. Anthony's central role in advancing women's rights evolved from her early activism, encompassing various strategic contributions that shaped the movement's development.

7.1. Early Women's Rights Advocacy

Anthony's work for the women's rights movement began as the movement was gaining momentum. While Elizabeth Cady Stanton had helped organize the local Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, the first women's rights convention, the movement gained national prominence with the first in a series of National Women's Rights Conventions held in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850. Anthony attended her first National Women's Rights Convention in 1852, held in Syracuse, New York, where she served as one of the convention's secretaries. According to Ida Husted Harper, Anthony's authorized biographer, Anthony left the Syracuse convention "thoroughly convinced that the right which woman needed above every other, the one indeed which would secure to her all others, was the right of suffrage." However, suffrage did not become the sole focus of her work for several more years.

A significant challenge for the early women's movement was a severe lack of funding. Few women at that time had independent sources of income, and even those who were employed were generally legally required to turn over their earnings to their husbands.

7.2. Campaigns for Legal Reforms

Partly due to the efforts of the burgeoning women's movement, a law recognizing some rights for married women had been passed in New York in 1848, though it was limited. In 1853, Anthony collaborated with William Henry Channing, her activist Unitarian minister, to organize a convention in Rochester. The goal was to launch a state campaign for improved property rights for married women, a campaign Anthony would lead. She embarked on a lecture and petition tour across almost every county in New York during the winter of 1855, despite the arduous travel conditions in snowy terrain by horse and buggy.

When she presented the petitions to the New York State Senate Judiciary Committee, its members sarcastically informed her that men were the truly oppressed sex, citing instances like men giving women the best seats in carriages. The committee's official report, noting petitions signed by both husbands and wives (instead of the standard practice of the husband signing for both), mockingly suggested a law authorizing husbands in such marriages to wear petticoats and wives trousers.

Despite this ridicule, the campaign ultimately succeeded in 1860 when the legislature passed an improved Married Women's Property Act. This landmark legislation granted married women the right to own separate property, enter into contracts, and be joint guardians of their children, significantly enhancing women's autonomy and equality. However, much of this law was rolled back in 1862, during a period when the women's movement was largely inactive due to the American Civil War.

At this time, the women's movement was loosely structured, with few state organizations and no national body beyond a coordinating committee for annual conventions. Lucy Stone, who had handled much of the organizational work for the national conventions, encouraged Anthony to take on some of this responsibility. Anthony initially resisted, feeling more needed in anti-slavery activities. After organizing a series of anti-slavery meetings in the winter of 1857, Anthony told a friend that her experience in anti-slavery work was more valuable to her than all her temperance and women's rights work, though the latter had been necessary training.

During a planning session for the 1858 women's rights convention, Stone, who had recently given birth, informed Anthony that her new family responsibilities would prevent her from organizing conventions until her children were older. Anthony presided over the 1858 convention, and when the planning committee for national conventions was reorganized, Stanton became its president and Anthony its secretary. Anthony continued to be heavily involved in anti-slavery work concurrently.

7.3. The Split in the Women's Movement

In May 1869, just two days after the final American Equal Rights Association (AERA) convention, Anthony, Stanton, and their allies formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In November 1869, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and others established the competing American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The intense rivalry between these two organizations created a partisan atmosphere that persisted for decades, even influencing later historical accounts of the women's movement.

The immediate catalyst for this division was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which aimed to prohibit the denial of suffrage based on race. In one of her most controversial actions, Anthony actively campaigned against this amendment. She and Stanton argued that women and African Americans should be enfranchised simultaneously. They contended that by effectively granting suffrage to all men while excluding all women, the amendment would establish an "aristocracy of sex," constitutionally endorsing the idea of male superiority over women. In 1873, Anthony powerfully articulated her opposition: "An oligarchy of wealth, where the rich govern the poor; an oligarchy of learning, where the educated govern the ignorant; or even an oligarchy of race, where the Saxon rules the African, might be endured; but surely this oligarchy of sex, which makes the men of every household sovereigns, masters; the women subjects, slaves; carrying dissension, rebellion into every home of the Nation, cannot be endured."

The AWSA, in contrast, supported the Fifteenth Amendment. Lucy Stone, who emerged as its most prominent leader, also made it clear that she believed that suffrage for women would ultimately benefit the country more than suffrage for black men.

Beyond the Fifteenth Amendment, the two organizations had other significant differences. The NWSA maintained political independence, while the AWSA, at least initially, sought close ties with the Republican Party, hoping that the amendment's ratification would lead to a Republican push for women's suffrage. The NWSA primarily focused on achieving suffrage at the national level through a constitutional amendment, whereas the AWSA pursued a state-by-state strategy. Furthermore, the NWSA initially addressed a broader range of women's issues, including divorce reform and equal pay for women, compared to the AWSA.

Events soon rendered much of the basis for the split irrelevant. In 1870, the debate over the Fifteenth Amendment concluded with its official ratification. By 1872, widespread disillusionment with government corruption led many abolitionists and social reformers to defect from the Republican Party to the short-lived Liberal Republican Party. As early as 1875, Anthony began advocating for the NWSA to focus more exclusively on women's suffrage rather than a wide array of women's issues. However, the animosity between the two women's groups was so severe that a merger proved impossible for two decades. The AWSA, particularly strong in New England, was the larger organization but began to decline in strength during the 1880s.

Finally, in 1890, the two organizations merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), with Stanton as president but with Anthony serving as its effective leader. When Stanton retired from her position in 1892, Anthony officially became NAWSA's president.

7.4. National Suffrage Organizations

After the formation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869, Susan B. Anthony fully dedicated herself to the organization and the cause of women's suffrage. She famously did not draw a salary from either the NWSA or its successor, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Instead, she used her earnings from lecturing to fund these organizations, demonstrating her profound personal commitment. At the time, there was no central national office for the movement; the mailing address was simply that of one of the officers.

Anthony's unmarried status provided her with a significant advantage in her work. Under the legal doctrine of coverture, a married woman had the status of feme covert, which, among other limitations, prevented her from signing contracts independently (her husband would do so on her behalf). As a feme sole (an unmarried woman), Anthony could freely sign contracts for convention halls, printed materials, and other necessities, giving her crucial autonomy in organizing.

Using the fees she earned from her extensive lecturing, Anthony was able to pay off the debts she had accumulated while supporting The Revolution newspaper. As her reputation grew, the press began treating her as a celebrity, making her a major draw for audiences. Throughout her career, she estimated that she delivered an average of 75 to 100 speeches per year. Early travel conditions were often arduous; she once gave a speech from atop a billiard table, and on another occasion, her train was snowbound for days, forcing her to subsist on crackers and dried fish.

Around 1870, both Anthony and Stanton embarked on regular lecture circuits, typically traveling from mid-autumn to spring. This timing was opportune, as the nation was beginning to seriously consider women's suffrage. While they occasionally traveled together, they more often toured separately. Lecture bureaus managed their schedules and travel arrangements, which typically involved traveling during the day and speaking at night, sometimes for weeks on end, including weekends. Their lectures effectively recruited new members into the movement, strengthening suffrage organizations at local, state, and national levels. Their travels during that decade covered a distance unmatched by any other reformer or politician of their time.

Anthony's other suffrage work included meticulously organizing national conventions, persistently lobbying both Congress and state legislatures, and participating in a seemingly endless series of state suffrage campaigns.

In 1890, the two major suffrage organizations, the NWSA and the AWSA, merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). While Elizabeth Cady Stanton was nominally the first president of NAWSA, Anthony was its effective leader, guiding its daily operations and strategic direction. When Stanton retired from her post in 1892, Anthony formally became NAWSA's president, a position she held until 1900.

7.5. State and National Suffrage Campaigns

Susan B. Anthony's efforts extended across numerous state and national campaigns, demonstrating her tireless dedication to securing voting rights for women. Her extensive travel and public speaking were central to these efforts. She delivered between 75 and 100 speeches annually, reaching audiences across the country and working on many state campaigns.

A unique opportunity arose in 1876, the year the U.S. celebrated its centennial as an independent nation. The NWSA sought permission to present a Declaration of Rights for Women at the official ceremony in Philadelphia, but their request was denied. Undeterred, Anthony, leading a group of five women, walked onto the platform during the ceremony and handed their Declaration to the astonished official in charge. As they departed, they distributed copies to the crowd. Spotting an unoccupied bandstand outside the hall, Anthony mounted it and read the Declaration aloud to a large gathering. Afterward, she invited everyone to an NWSA convention at a nearby Unitarian church, where prominent speakers like Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton awaited them.

The collective work of the women's suffrage movement, significantly driven by Anthony's efforts, began to yield tangible results. Women gained the right to vote in Wyoming in 1869 and in Utah in 1870. Anthony's lectures in Washington and four other states directly led to invitations for her to address their respective state legislatures, a testament to her growing influence and the increasing acceptance of the suffrage cause.

By the mid-1880s, major advocacy groups began to officially support women's suffrage. The Grange, a large and influential farmers' organization, endorsed women's suffrage as early as 1885. The Women's Christian Temperance Union, the largest women's organization in the country, also threw its support behind the suffrage movement, significantly broadening its base.

Anthony's unwavering commitment, her spartan lifestyle, and her refusal to seek personal financial gain made her an exceptionally effective fundraiser. These qualities also earned her the admiration of many, even those who did not fully agree with her goals. As her reputation grew, her working and travel conditions improved. She sometimes had access to the private railroad car of Jane Stanford, a sympathizer whose husband owned a major railroad. While lobbying and preparing for the annual suffrage conventions in Washington, she was provided with a complimentary suite of rooms in the Riggs Hotel, whose owners supported her work.

To ensure the continuity of the movement, Anthony dedicated herself to training a new generation of younger activists, affectionately known as her "nieces." Two of these proteges, Carrie Chapman Catt and Anna Howard Shaw, went on to serve as presidents of the NAWSA after Anthony retired from her leadership position, ensuring the movement's momentum continued towards its ultimate goal.

7.6. The Susan B. Anthony Amendment

The culmination of Susan B. Anthony's relentless advocacy for women's suffrage was the proposed constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. In 1878, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton arranged for this amendment to be formally presented to Congress. Introduced by Senator Aaron A. Sargent (Republican from California), it became colloquially known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, a testament to her pioneering and persistent efforts.

This amendment, after decades of tireless campaigning, lobbying, and public education by Anthony and countless other suffragists, was eventually ratified as the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. Its passage marked the successful conclusion of the long struggle for women's suffrage in the United States, a victory that Anthony, though she did not live to see it, had dedicated her entire adult life to achieving. The amendment's popular name forever links her name to this monumental achievement in American democratic history.

8. Key Publications and Projects

Susan B. Anthony made significant contributions to documenting and disseminating the goals and history of the women's rights movement, ensuring its narrative and achievements were preserved.

8.1. The Revolution Newspaper

Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton began publishing a weekly newspaper titled The Revolution in New York City in 1868. The newspaper primarily focused on women's rights, particularly women's suffrage, but it also covered a wide array of other topics, including politics, the labor movement, and finance. Its bold motto declared: "Men, their rights and nothing more: women, their rights and nothing less."

One of the newspaper's key objectives was to provide a forum for women to exchange opinions on critical issues from diverse viewpoints. Anthony managed the business aspects of the paper, while Stanton served as co-editor alongside Parker Pillsbury, an abolitionist and staunch supporter of women's rights. Initial funding for The Revolution was provided by George Francis Train, a wealthy but controversial businessman who supported women's rights but alienated many activists with his political and racial views.

In the aftermath of the American Civil War, many major periodicals associated with radical social reform movements had either become more conservative or ceased publication. Anthony intended for The Revolution to partially fill this void, with aspirations of eventually expanding it into a daily paper with its own printing press, all owned and operated by women. However, the funding arranged by Train was less than Anthony had anticipated. Moreover, Train sailed for England shortly after the first issue of The Revolution was published and was soon jailed for supporting Irish independence.

Train's financial support eventually vanished entirely. After twenty-nine months, mounting debts forced Anthony to transfer ownership of the paper to Laura Curtis Bullard, a wealthy women's rights activist who gave it a less radical tone. The newspaper published its final issue less than two years later.

Despite its relatively short lifespan, The Revolution served as a crucial platform for Anthony and Stanton to articulate their views during the developing split within the women's movement. It also played a vital role in promoting their wing of the movement, which ultimately evolved into a separate organization.

Anthony also attempted to forge an alliance with the labor movement through The Revolution. The National Labor Union (NLU), formed in 1866, began reaching out to farmers, African Americans, and women with the aim of creating a broad-based political party. The Revolution responded enthusiastically, proclaiming, "The principles of the National Labor Union are our principles." It predicted that "The producers-the working-men, the women, the negroes-are destined to form a triple power that shall speedily wrest the sceptre of government from the non-producers-the land monopolists, the bond-holders, the politicians." Anthony and Stanton were seated as delegates to the NLU Congress in 1868, with Anthony representing the Working Women's Association (WWA), which had recently been formed in The Revolution's offices.

However, this attempted alliance was short-lived. During a printers' strike in 1869, Anthony voiced approval of an employer-sponsored training program that would teach women skills enabling them to effectively replace the strikers. Anthony saw this program as an opportunity to increase employment for women in a trade from which they were often excluded by both employers and unions. At the subsequent NLU Congress, Anthony was initially seated as a delegate but then unseated due to strong opposition from those who accused her of supporting strikebreakers.

Anthony worked with the WWA to form all-female labor unions, though with limited success. She achieved more in her collaboration with the WWA and The Revolution on a joint campaign to secure a pardon for Hester Vaughn, a domestic worker convicted of infanticide and sentenced to death. Arguing that the social and legal systems treated women unfairly, the WWA petitioned, organized a mass meeting where Anthony was a speaker, and sent delegations to visit Vaughn in prison and to speak with the governor. Vaughn was eventually pardoned.

Initially comprising over a hundred wage-earning women, the WWA evolved into an organization almost entirely composed of middle-class working women, such as journalists and doctors. Its members formed the core of the New York City contingent of the new national suffrage organization that Anthony and Stanton were establishing.

8.2. History of Woman Suffrage

In 1876, Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton embarked on the monumental project of writing a comprehensive history of the women's suffrage movement. For years, Anthony had meticulously collected and preserved letters, newspaper clippings, and other materials of historical value to the women's movement. In 1876, she moved into the Stanton household in New Jersey, bringing with her several trunks and boxes filled with these materials, to begin work on the History of Woman Suffrage.

Despite its critical importance, Anthony found this type of work personally arduous. In her letters, she expressed her dislike for the project, stating it "makes me feel growly all the time ... No warhorse ever panted for the rush of battle more than I for outside work. I love to make history but hate to write it."

The project consumed a significant portion of her time for several years, even as she continued to engage in other women's suffrage activities. Anthony took on the role of her own publisher, which presented various challenges, including finding adequate storage space for the inventory. She was eventually forced to limit the number of books she was storing in the attic of her sister's house because their weight threatened to collapse the structure.

Originally conceived as a modest publication that could be produced quickly, the history evolved into a six-volume work spanning more than 5,700 pages, compiled over a period of 41 years. The first three volumes, which cover the movement up to 1885, were published between 1881 and 1886 and were authored by Stanton, Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Anthony was responsible for managing the production details and handling the extensive correspondence with contributors. Volume 4, covering the period from 1883 to 1900, was published by Anthony in 1902, after Stanton's death, with the assistance of Ida Husted Harper, Anthony's designated biographer. The final two volumes, which bring the history up to 1920, were completed in 1922 by Harper after Anthony's own passing.

The History of Woman Suffrage is an invaluable resource, preserving an enormous amount of material that might otherwise have been lost forever. However, because it was written by leaders of one wing of the divided women's movement (Lucy Stone, their main rival, refused to participate in the project), it does not offer a completely balanced view of events concerning their rivals. It tends to overstate the roles of Anthony and Stanton while understating or entirely ignoring the contributions of Stone and other activists who did not align with the historical narrative that Anthony and Stanton developed. For many years, this work served as the primary source of documentation about the suffrage movement, necessitating that later historians uncover other sources to provide a more balanced perspective.

9. Civil Disobedience and Legal Challenges

Susan B. Anthony's direct actions to challenge discriminatory laws and her subsequent legal battles brought significant national attention to the cause of women's suffrage.

9.1. Attempted Voting and Trial

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) convention of 1871 adopted a bold strategy: urging women to attempt to vote, and if turned away, to file lawsuits in federal courts to challenge laws that prevented women from voting. The legal basis for this challenge was the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment, which states, in part: "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States."

Following the example set by Anthony and her sisters shortly before election day, nearly fifty women in Rochester registered to vote in the presidential election of 1872. On election day, November 5, 1872, Anthony and fourteen other women from her ward successfully convinced the election inspectors to allow them to cast ballots. However, women in other wards were turned away. Anthony was arrested on November 18, 1872, by a U.S. Deputy Marshal and charged with illegally voting. The other women who had voted were also arrested but were released pending the outcome of Anthony's trial.

Anthony's trial generated national controversy and marked a major turning point, transforming the broader women's rights movement into a focused women's suffrage movement. Before her trial, which was to be held in Monroe County, New York, where the jurors would be chosen, Anthony embarked on a speaking tour throughout the county. Her speech, titled "Is it a Crime for a U.S. Citizen to Vote?", declared, "We no longer petition Legislature or Congress to give us the right to vote. We appeal to women everywhere to exercise their too long neglected 'citizen's right to vote."

The U.S. Attorney, seeking to ensure a conviction, arranged for the trial to be moved to the federal circuit court, which would soon convene in neighboring Ontario County with a jury drawn from that county's inhabitants. Anthony responded by extending her speaking tour throughout Ontario County before the trial began, ensuring that potential jurors were exposed to her arguments.

Responsibility for that federal circuit rested with Justice Ward Hunt, who had recently been appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Hunt had no prior experience as a trial judge, having begun his judicial career as an elected judge on the New York Court of Appeals.

The trial, United States v. Susan B. Anthony, commenced on June 17, 1873, and was closely followed by the national press. Adhering to a common law rule of the time that prevented criminal defendants in federal courts from testifying, Justice Hunt refused to allow Anthony to speak until the verdict had been delivered. On the second day of the trial, after both sides had presented their cases, Justice Hunt delivered his lengthy, pre-written opinion. In the most controversial aspect of the trial, Hunt directly instructed the jury to deliver a guilty verdict, effectively denying Anthony a trial by jury.

After the verdict was delivered, Justice Hunt asked Anthony if she had anything to say. She responded with what historian Ann D. Gordon called "the most famous speech in the history of the agitation for woman suffrage." Repeatedly ignoring the judge's orders to stop talking and sit down, she protested what she called "this high-handed outrage upon my citizen's rights," asserting, "you have trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored." She chastised Justice Hunt for denying her a trial by jury, further stating that even if he had allowed the jury to discuss the case, she still would have been denied a trial by a jury of her peers because women were not permitted to be jurors.

In a speech to the Union League Club in New York on December 16, 1873, on the centennial of the Boston Tea Party, Anthony declared: "I stand before you tonight a convicted criminal... convicted by a Supreme Court Judge... and sentenced to pay 100 USD fine and costs. For what? For asserting my right to representation in a government, based upon the one idea of the right of every person governed to participate in that government. This is the result at the close of 100 years of this government, that I, a native born American citizen, am found guilty of neither lunacy nor idiocy, but of a crime-simply because I exercised our right to vote."

When Justice Hunt sentenced Anthony to pay a fine of 100 USD, she defiantly responded, "I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty," and she never did. Had Hunt ordered her jailed until she paid the fine, Anthony could have appealed her case to the Supreme Court. However, Hunt announced he would not order her taken into custody, thereby closing off that legal avenue for appeal.

The U.S. Supreme Court in 1875 effectively ended the strategy of trying to achieve women's suffrage through the court system when it ruled in Minor v. Happersett that "the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone." Following this ruling, the NWSA decided to pursue the far more difficult strategy of campaigning for a constitutional amendment to secure voting rights for women.

On August 18, 2020, the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, President Donald Trump announced he would pardon Anthony, 148 years after her conviction. However, the president of the National Susan B. Anthony Museum and House publicly "declined" the offer of a pardon, stating that accepting it would wrongly "validate" the trial proceedings, just as paying the 100 USD fine would have.

10. International Work and Influence

Susan B. Anthony's vision for women's rights extended beyond national borders, leading her to foster international cooperation and advocacy for global women's suffrage movements.

10.1. International Council of Women (ICW)

In 1883, Anthony embarked on a nine-month stay in Europe, where she reunited with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had arrived months earlier. Together, they met with leaders of European women's movements, initiating the process of creating a global women's organization.

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), Anthony's organization, agreed to host the founding congress of this international body. The preparatory work was primarily handled by Anthony and two of her younger colleagues from the NWSA, Rachel Foster Avery and May Wright Sewall. In 1888, delegates from fifty-three women's organizations across nine countries convened in Washington, D.C., to establish the new association, named the International Council of Women (ICW). The delegates represented a wide array of organizations, including suffrage associations, professional groups, literary clubs, temperance unions, labor leagues, and missionary societies. Notably, the American Woman Suffrage Association, which had been a rival to the NWSA for years, also participated in the congress, marking a significant step towards unity. Anthony opened the first session of the ICW and presided over most of its events.

The ICW quickly garnered respect at the highest levels of government and society. President Cleveland and his wife hosted a reception at the White House for delegates attending the ICW's founding congress. The ICW's second congress was an integral part of the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. At its third congress in London in 1899, a reception for the ICW was held at Windsor Castle at the invitation of Queen Victoria. During its fourth congress in Berlin in 1904, Augusta Victoria, the German Empress, received the ICW leaders at her palace. Anthony played a prominent role on all four of these significant occasions. The ICW remains active today and is associated with the United Nations.

10.2. International Alliance of Women (IAW)

After Susan B. Anthony retired as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), her chosen successor, Carrie Chapman Catt, began working towards establishing an international women's suffrage association, a long-held goal of Anthony's. The existing International Council of Women (ICW) was not expected to explicitly support a campaign for women's suffrage because its broad alliance included more conservative members who would object.

In 1902, Catt organized a preparatory meeting in Washington, D.C., with Anthony serving as chair, attended by delegates from several countries. Primarily organized by Catt, the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) was officially created in Berlin in 1904. Anthony chaired the founding meeting and was declared the new organization's honorary president and first member. According to Anthony's authorized biographer, Ida Husted Harper, "no event ever gave Miss Anthony such profound satisfaction as this one."

The organization was later renamed the International Alliance of Women (IAW) and remains active today, affiliated with the United Nations. Anthony's involvement in its founding cemented her legacy as a global advocate for women's rights and suffrage.

11. Later Life and Continued Advocacy

In her later years, Susan B. Anthony continued her tireless advocacy for women's rights, her influence growing as public perception of her work evolved.

11.1. Role in NAWSA Leadership

Having spent years living in hotels and with friends and relatives due to her extensive travels, Anthony agreed to settle into her sister Mary Stafford Anthony's house in Rochester in 1891, at the age of 71. Her remarkable energy and stamina, which sometimes exhausted her co-workers, persisted at an extraordinary level. At 75, she even toured Yosemite National Park on the back of a mule.

She remained a prominent leader of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and continued to travel extensively for suffrage work. Beyond national efforts, she also engaged in significant local projects. In 1893, she initiated the Rochester branch of the Women's Educational and Industrial Union. In 1898, she convened a meeting of 73 local women's societies to form the Rochester Council of Women. She played a pivotal role in raising the funds required by the University of Rochester before they would admit women students, even pledging her life insurance policy to close the final funding gap.

In 1896, she spent eight months on the California suffrage campaign, speaking as many as three times per day in over 30 localities. In 1900, she presided over her last NAWSA convention. During the remaining six years of her life, Anthony continued to be active, speaking at six more NAWSA conventions and four congressional hearings, completing the fourth volume of the History of Woman Suffrage, and traveling to eighteen states and to Europe.

11.2. Public Recognition and Honors

As Anthony's fame grew, some politicians, though not all, became eager to be publicly associated with her. Her seventieth birthday was celebrated at a national event in Washington, D.C., with prominent members of the House and Senate in attendance. Her eightieth birthday was a particularly notable occasion, celebrated at the White House at the invitation of President William McKinley, signifying her elevated national stature.

This shift in public perception was remarkable. When she first began campaigning for women's rights, Anthony was often harshly ridiculed and accused of attempting to destroy the institution of marriage. However, this perception changed radically during her lifetime, transforming her into a revered national figure. She became the first female citizen to be depicted on U.S. coinage when her portrait appeared on the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin, first issued in 1979, long after her death but a testament to her enduring legacy.

12. Views on Social Issues

Susan B. Anthony held progressive views on various social and personal matters, consistently reflecting her commitment to equality and individual rights.

12.1. Religious and Spiritual Beliefs

Anthony was raised a Quaker, but her religious heritage was diverse. Her maternal grandmother was a Baptist, and her grandfather was a Universalist. Her father was a radical Quaker who often clashed with the restrictions of his more conservative congregation. When the Quakers split in the late 1820s into Orthodox and Hicksites, her family aligned with the Hicksites, which Anthony described as "the radical side, the Unitarian."

In 1848, three years after the Anthony family moved to Rochester, a group of about 200 Quakers withdrew from the Hicksite organization in western New York, partly to pursue social reform movements without interference. Some of these individuals, including the Anthony family, began attending services at the First Unitarian Church of Rochester. When Susan B. Anthony returned home from teaching in 1849, she joined her family in attending services there and remained affiliated with the Rochester Unitarians for the rest of her life. Her spiritual outlook was significantly influenced by William Henry Channing, a nationally recognized minister of that church who also assisted her with several reform projects. Anthony was listed as a member of First Unitarian in an 1881 church history.

Despite her Unitarian affiliation, Anthony remained proud of her Quaker roots and continued to describe herself as a Quaker. She maintained her membership in the local Hicksite body but did not attend its meetings. She also joined the Congregational Friends, an organization formed by Quakers in western New York after the 1848 split. This group soon ceased to operate as a religious body, renaming itself the Friends of Human Progress and organizing annual meetings in support of social reform that welcomed everyone, including "Christians, Jews, Mahammedans, and Pagans." Anthony served as secretary of this group in 1857.

In 1859, during a period when Rochester Unitarians were struggling with factionalism, Anthony unsuccessfully attempted to establish a "Free church in Rochester... where no doctrines should be preached and all should be welcome." She modeled this on the Boston church of Theodore Parker, a Unitarian minister who influenced his denomination by rejecting the authority of the Bible and the validity of miracles. Anthony later became close friends with William Channing Gannett, who became the minister of the Unitarian Church in Rochester in 1889, and his wife Mary, who came from a Quaker background. William had been a national leader in the successful movement within the Unitarian denomination to end the practice of binding it by a formal creed, thereby opening its membership to non-Christians and even non-theists, a goal that mirrored Anthony's vision for her proposed Free church.

After reducing her arduous travel schedule and making her home in Rochester in 1891, Anthony resumed regular attendance at First Unitarian and collaborated with the Gannetts on local reform projects. Her sister Mary Stafford Anthony, whose home had provided a resting place for Anthony during her years of frequent travel, had long been an active member of this church.

While her first public speech, delivered at a temperance meeting as a young woman, contained frequent references to God, Anthony soon adopted a more critical approach. While in Europe in 1883, she helped a desperately poor Irish mother of six children. Noting that "the evidences were that 'God' was about to add a No. 7 to her flock," Anthony later commented, "What a dreadful creature their God must be to keep sending hungry mouths while he withholds the bread to fill them!"

Elizabeth Cady Stanton described Anthony as an agnostic, adding, "To her, work is worship... Her belief is not orthodox, but it is religious." Anthony herself stated, "Work and worship are one with me. I can not imagine a God of the universe made happy by my getting down on my knees and calling him 'great." When her sister Hannah was on her deathbed and asked Susan to discuss the afterlife, Anthony later wrote, "I could not dash her faith with my doubts, nor could I pretend a faith I had not; so I was silent in the dread presence of death." When an organization offered to sponsor a women's rights convention on the condition that "no speaker should say anything which would seem like an attack on Christianity," Anthony wrote to a friend, "I wonder if they'll be as particular to warn all other speakers not to say anything which shall sound like an attack on liberal religion. They never seem to think we have any feelings to be hurt when we have to sit under their reiteration of orthodox cant and dogma."

12.2. Perspectives on Marriage and Family

As a teenager, Susan B. Anthony attended parties, and she received marriage proposals later in life, but there is no record of her ever engaging in a serious romantic relationship. Despite this, Anthony deeply loved children and played a significant role in helping to raise the children in the Stanton household. She once wrote, "The dear little Lucy engrosses most of my time and thoughts. A child one loves is a constant benediction to the soul, whether or not it helps to the accomplishment of great intellectual feats."

As a young activist in the women's rights movement, Anthony expressed frustration when some of her co-workers married and had children, which sharply curtailed their ability to work for the understaffed movement. When Lucy Stone broke her pledge to remain single, Anthony's scolding remarks caused a temporary rift in their friendship. Journalists frequently asked Anthony to explain why she never married. To one, she replied, "It always happened that the men I wanted were those I could not get, and those who wanted me I wouldn't have." To another, she stated, "I never found the man who was necessary to my happiness. I was very well as I was." To a third, she famously explained, "I never felt I could give up my life of freedom to become a man's housekeeper. When I was young, if a girl married poor, she became a housekeeper and a drudge. If she married wealth she became a pet and a doll. Just think, had I married at twenty, I would have been a drudge or a doll for fifty-nine years. Think of it!"

Anthony fiercely opposed laws that granted husbands complete control over the marriage. Blackstone's Commentaries, which formed the basis for legal systems in most states at the time, famously stated, "By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage." This legal framework effectively subsumed a woman's identity into her husband's, stripping her of independent legal standing.

In a speech in 1877, Anthony predicted "an epoch of single women." She posited that "If women will not accept marriage with subjugation, nor men proffer it without, there is, there can be, no alternative. The woman who will not be ruled must live without marriage." This statement underscored her belief that true equality for women might necessitate a reevaluation of traditional marital structures, emphasizing individual autonomy and challenging societal expectations for women within domestic life.

12.3. Stance on Abortion

Susan B. Anthony showed little direct interest in the topic of abortion. Ann D. Gordon, who led the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers project, a significant undertaking to collect and document materials written by Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, stated that Anthony "never voiced an opinion about the sanctity of fetal life... and she never voiced an opinion about using the power of the state to require that pregnancies be brought to term." Similarly, Lynn Sherr, author of a biography of Anthony, noted that she "looked desperately for some kind of evidence one way or the other as to what her position was, and it just wasn't there."

A dispute over Anthony's views on abortion developed after 1989 when some members of the anti-abortion movement began to portray Anthony as "an outspoken critic of abortion," citing various statements they attributed to her. The anti-abortion advocacy group Susan B. Anthony List named itself after her on this basis. However, historians like Gordon and Sherr, among others, have contested this portrayal, asserting that the cited statements were either not made by Anthony, were not about abortion, or had been taken out of context. This ongoing debate highlights the complexities of interpreting historical figures' views through a modern lens, especially when explicit statements on a specific issue are scarce.

13. Death and Enduring Legacy

Susan B. Anthony passed away at the age of 86 from heart failure and pneumonia in her home in Rochester, New York, on March 13, 1906. She was laid to rest at Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester.

13.1. Death

Just a few days before her death, at her birthday celebration in Washington, D.C., Anthony spoke of the many individuals who had worked alongside her for women's rights: "There have been others also just as true and devoted to the cause-I wish I could name every one-but with such women consecrating their lives, failure is impossible!" This powerful declaration, "Failure is impossible," quickly became a rallying cry and watchword for the women's movement.

13.2. Impact on Women's Rights and Society

Anthony did not live to witness the achievement of women's suffrage at the national level, but she expressed profound pride in the significant progress the women's movement had made during her lifetime. At the time of her death, women had already secured suffrage in four states: Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho. Several larger states soon followed suit. Legal rights for married women had been established in most states, and women were increasingly entering various professions. Notably, 36,000 women were attending colleges and universities, a dramatic increase from virtually none just a few decades prior. Two years before her passing, Anthony observed, "The world has never witnessed a greater revolution than in the sphere of woman during this fifty years."

Part of this revolution, in Anthony's view, was a fundamental shift in ways of thinking. In an 1889 speech, she noted that women had historically been taught that their primary purpose was to serve men. However, she observed, "Now, after 40 years of agitation, the idea is beginning to prevail that women were created for themselves, for their own happiness, and for the welfare of the world." Anthony was confident that women's suffrage would eventually be achieved, but she also feared that future generations might forget the immense difficulty and struggle involved in securing it, just as people were already forgetting the ordeals of the recent past:

"We shall someday be heeded, and when we shall have our amendment to the Constitution of the United States, everybody will think it was always so, just exactly as many young people think that all the privileges, all the freedom, all the enjoyments which woman now possesses always were hers. They have no idea of how every single inch of ground that she stands upon today has been gained by the hard work of some little handful of women of the past."

Anthony's death was widely mourned across the nation. Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, remarked just before Anthony's death, "A few days ago someone said to me that every woman should stand with bared head before Susan B. Anthony. 'Yes,' I answered, 'and every man as well.' ... For ages he has been trying to carry the burden of life's responsibilities alone... Just now it is new and strange and men cannot comprehend what it would mean but the change is not far away."

In her seminal history of the women's suffrage movement, Eleanor Flexner eloquently summarized Anthony's unique contribution: "If Lucretia Mott typified the moral force of the movement, if Lucy Stone was its most gifted orator and Elizabeth Cady Stanton its most outstanding philosopher, Susan Anthony was its incomparable organizer, who gave it force and direction for half a century."

The Nineteenth Amendment, which prohibited the denial of suffrage based on sex, became colloquially known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. After its ratification in 1920, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), whose character and policies were profoundly influenced by Anthony, transformed into the League of Women Voters, which remains an active force in U.S. politics today.

13.3. Commemorations and Memorials

Susan B. Anthony is honored in various ways, reflecting her lasting significance in American history and her profound impact on women's rights.

13.3.1. Halls of Fame

In 1950, Anthony was inducted into the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. A bust of her, sculpted by Brenda Putnam, was placed there in 1952. In 1973, Anthony was also inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

13.3.2. Artwork and Monuments

The first memorial to Susan B. Anthony was established by African Americans. In 1907, a year after Anthony's death, a stained-glass window was installed at the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church in Rochester. The window featured her portrait and the words "Failure is Impossible," a quote from Anthony that had become a watchword for the women's suffrage movement. This memorial was realized through the efforts of Hester C. Jeffrey, the president of the Susan B. Anthony Club, an organization of African American women in Rochester. Speaking at the window's dedication, Jeffrey stated, "Miss Anthony had stood by the Negroes when it meant almost death to be a friend of the colored people." This church had a historical connection to social justice, as Frederick Douglass printed the first editions of The North Star, his abolitionist newspaper, in its basement in 1847.

Anthony is commemorated alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott in the Portrait Monument sculpture by Adelaide Johnson at the United States Capitol. Unveiled in 1921, the sculpture was initially displayed in the crypt of the U.S. Capitol before being moved to its current, more prominent location in the rotunda in 1997.

In 1922, sculptor Leila Usher donated a bas-relief of Susan B. Anthony to the National Woman's Party, which was installed at their headquarters near Washington, DC. Usher also created a similar bronze medallion donated to Bryn Mawr College in 1901.

In 1999, a sculpture by Ted Aub commemorating the introduction of Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton by Amelia Bloomer on May 12, 1851, was unveiled. Titled "When Anthony Met Stanton," it features life-size bronze statues of the three women near Van Cleef Lake in Seneca Falls, New York, where the introduction occurred.

In 2001, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan, one of the world's largest cathedrals, added a sculpture honoring Anthony alongside three other 20th-century heroes: Martin Luther King Jr., Albert Einstein, and Mahatma Gandhi.

An installation artwork by Judy Chicago called The Dinner Party, first exhibited in 1979, includes a place setting dedicated to Anthony.

A bronze sculpture featuring a locked ballot box flanked by two pillars marks the spot where Anthony voted in 1872 in defiance of laws prohibiting women from voting. This "1872 Monument" was dedicated in August 2009, on the 89th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment. Leading away from the monument is the Susan B. Anthony Trail, which runs beside the 1872 Café, named for the year of Anthony's vote. Near the Susan B. Anthony Museum and House is the "Let's Have Tea" sculpture of Anthony and Frederick Douglass created by Pepsy Kettavong.

On February 15, 2020, Google celebrated Anthony's 200th birthday with a Google Doodle.

13.3.3. Landmarks

Anthony's home in Rochester, New York is designated a National Historic Landmark and is known as the National Susan B. Anthony Museum and House. Her birth home in Adams, Massachusetts, and her childhood home in Battenville, New York, are both listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2007, the new Frederick Douglass-Susan B. Anthony Memorial Bridge replaced the old Troup-Howell Bridge, carrying expressway traffic on Interstate 490 through downtown Rochester, further cementing her connection to the city.

The Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers project was an academic undertaking to collect and document all available materials written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Anthony. The project began in 1982 and has since been completed. In 1999, Ken Burns and others produced the television documentary Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony.

13.3.4. Currency, Coins, and Stamps

The U.S. Post Office issued its first postage stamp honoring Anthony in 1936, on the 16th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which ensured women's right to vote. A second stamp honoring Anthony was issued in April 1958.

In 1979, the United States Mint began issuing the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin, marking the first time a female citizen was honored on a U.S. coin.

The U.S. Treasury Department announced on April 20, 2016, that an image of Anthony would appear on the back of a newly designed $10 bill, alongside Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul. The original plan had considered Anthony for the front of the $10 bill, but the final decision was for Alexander Hamilton, the first US Secretary of the Treasury, to retain his position there. Designs for new $5, $10, and $20 bills were slated to be unveiled in 2020, coinciding with the 100th anniversary of American women gaining the right to vote via the 19th Amendment.

13.3.5. Awards and Organization Names

Since 1970, the Susan B. Anthony Award has been given annually by the New York City chapter of the National Organization for Women to honor "grassroots activists dedicated to improving the lives of women and girls in New York City."

New York Radical Feminists, founded in 1969, organized into small cells or "brigades" named after notable feminists of the past. The Stanton-Anthony Brigade was notably led by Anne Koedt and Shulamith Firestone.

In 1971, Zsuzsanna Budapest founded the Susan B. Anthony Coven #1, which was the first feminist, women-only, witches' coven. The Susan B. Anthony List is a non-profit organization that seeks to reduce and ultimately end abortion in the U.S.

Susan B. Anthony Day is a commemorative holiday celebrated on February 15, Anthony's birthday, to honor her birth and the cause of women's suffrage in the United States.

In 2016, Lovely Warren, the mayor of Rochester, placed a red, white, and blue sign next to Anthony's grave the day after Hillary Clinton secured the nomination at the Democratic National Convention. The sign read, "Dear Susan B., we thought you might like to know that for the first time in history, a woman is running for president representing a major party. 144 years ago, your illegal vote got you arrested. It took another 48 years for women to finally gain the right to vote. Thank you for paving the way." The city of Rochester shared pictures of the message on Twitter and encouraged residents to visit Anthony's grave to sign it.

14. See Also

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Susan B. Anthony abortion dispute

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

- Women's suffrage organizations

- Susan B. Anthony dollar

- Susan B. Anthony Day