1. Early Life and Amateur Career

Stephen Dalkowski's early life and athletic pursuits laid the foundation for his remarkable, albeit challenging, baseball career.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Dalkowski was born on June 3, 1939, in New Britain, Connecticut. He came from a family of Polish immigrant heritage. His mother, Adele Zaleski, worked in a ball bearing factory, while his father, Stephen Dalkowski, was employed as a tool and die maker.

1.2. High School Years and Early Athletic Achievements

Dalkowski began playing baseball in high school, and also excelled in American football as a quarterback for New Britain High School. During his time with the football team, they achieved success by winning the division championship twice, in 1955 and 1956. However, it was in baseball that Dalkowski truly distinguished himself. He still holds a Connecticut state record for striking out 24 batters in a single game, a testament to his early pitching dominance.

2. Professional Baseball Career

Stephen Dalkowski's professional baseball career was exclusively spent in the minor leagues, marked by his legendary fastball, severe control issues, and a career-altering injury.

2.1. Minor League Debut and Early Years

After graduating from high school in 1957, Dalkowski signed with the Baltimore Orioles for a signing bonus of 4.00 K USD. He began his professional career with their Class D minor league affiliate in Kingsport, Tennessee. Dalkowski spent his entire nine-year career in the minor leagues, playing in nine different leagues. His only appearance at the Orioles' Memorial Stadium was during an exhibition game in 1959, where he famously struck out the opposing side.

2.2. Pitching Style and Fastball Velocity

Dalkowski's primary claim to fame was the extraordinary velocity of his fastball. Despite his average height, he possessed wide shoulders and an exceptionally developed shoulder musculature. His raw speed was further enhanced by his highly flexible left (pitching) arm and an unusual "buggy-whip" pitching motion that concluded with a cross-body arm swing. Dalkowski himself recalled hitting his left elbow on his right knee so frequently that a protective pad was eventually made for him to wear.

Accurate measurements of pitch velocity were difficult in Dalkowski's era due to the absence of radar guns and other precise measuring devices. Therefore, the actual top speed of his pitches remains unknown and is largely based on anecdotal evidence. However, there is a strong consensus that Dalkowski consistently threw well over 100 mph. Some observers and experts believed his fastball reached speeds as high as 110 mph, 115 mph, 120 mph, or even 125 mph. Conversely, others suggested his pitches traveled at less than these speeds. Renowned umpire Doug Harvey stated that "Nobody could bring it like he could." Legendary hitter Ted Williams, after facing Dalkowski once in a spring training game, famously declared, "Fastest ever. I never want to face him again." The velocity of his fastball earned him the nickname "White Lightning".

The only recorded evidence of Dalkowski's pitching speed comes from a 1958 test at Aberdeen Proving Ground, a military installation, using a radar machine. He was clocked at 93.5 mph, a fast but not exceptional speed for a professional pitcher. However, several factors likely influenced this measurement: Dalkowski had pitched a game the day before, he was throwing from a flat surface rather than a pitcher's mound, and he had to throw pitches for 40 minutes at a small target before an accurate measurement could be captured. Additionally, the device measured speed from a few feet away from the plate, rather than 10 ft from release as in modern measurements, which could have accounted for an approximate 9 mph reduction.

For comparison, Nolan Ryan, a former record holder for fastest pitch, was clocked at 100.9 mph in 1974. Modern pitching speed measurements are taken from 10 ft from release, unlike older methods that measured closer to the plate, potentially accounting for differences of up to 10 mph. Earl Weaver, who managed both Dalkowski and Ryan, stated, "[Dalkowski] threw a lot faster than Ryan." The fastest recorded pitches in modern baseball, as of 2020, are 105.1 mph by Aroldis Chapman and Jordan Hicks. Scientists generally contend that the theoretical maximum speed a pitcher can throw is slightly above 100 mph, beyond which serious injury would occur.

2.3. Struggles with Control and Career Setbacks

Dalkowski was infamous for his extreme difficulty in controlling his pitches, often walking more batters than he struck out. His pitches were frequently wild, sometimes sailing into the stands. Batters found the combination of extreme velocity and lack of control highly intimidating. Oriole Paul Blair described him as "the hardest I ever saw" and "the wildest I ever saw." Ted Williams reportedly joked about the pitches being "too fast."

In a typical season in 1960, while pitching in the California League, Dalkowski struck out 262 batters and walked 262 in 170 innings, resulting in rates of 13.81 strikeouts and 13.81 walks per nine innings. By comparison, Randy Johnson holds the major league record for strikeouts per nine innings in a season with 13.41. In separate games, Dalkowski once struck out 21 batters and in another, walked 21 batters. On August 31, 1957, pitching for the Kingsport Orioles against Bluefield, he struck out 24 batters but lost the game 8-4, issuing 18 walks, 4 hit by pitches, and throwing 6 wild pitches. For the entire 1957 season, Dalkowski pitched 62 innings, striking out 121 (averaging 18 strikeouts per game) but recording only one win due to 129 walks and 39 wild pitches. In 1958 in the Northern League, he pitched a one-hitter but lost 9-8 due to 17 walks. From 1957 to 1958, Dalkowski either struck out or walked almost three out of every four batters he faced.

His wildness led to numerous legendary anecdotes. One story claims a Dalkowski pitch tore off part of a batter's ear, an incident some observers believed contributed to his increasing nervousness and wildness. Another tale from 1960 in Stockton, California, recounts Dalkowski throwing a pitch that shattered umpire Doug Harvey's mask in three places, knocking him 18 ft back and sending him to the hospital for three days with a concussion. Dalkowski once won a 5 USD bet with teammate Herm Starrette by throwing a baseball through a wooden outfield fence from 15 ft away. Another bet involved him throwing a ball over a fence 440 ft away. Other tales include Dalkowski throwing 120 pitches in two innings before being pulled, and his pitches creating multiple holes in a wooden fence when he tried to hit a strike zone drawn on it.

2.4. Major League Aspirations and Injury

Under the management of Earl Weaver, then manager for the Orioles' Double-A affiliate in Elmira, New York, Dalkowski's game began to show improvement during the 1960s. Weaver, after administering IQ tests to his players, found Dalkowski to have a lower than normal IQ (around 75, close to the threshold for intellectual disability). Believing Dalkowski's struggles with control stemmed partly from his mental capacity, Weaver simplified his instructions: Dalkowski was to throw only his fastball and a slider, aiming the fastball down the middle of the plate. This approach allowed Dalkowski to focus solely on throwing strikes, as Weaver recognized that his fastball was virtually unhittable even if he missed his target slightly.

Under Weaver's guidance, Dalkowski had his best season in 1962, achieving personal bests in complete games and earned run average (ERA), and, for the first time in his career, walking less than a batter per inning. In an extra-inning game that year, Dalkowski famously recorded 27 strikeouts while also walking 16 batters and throwing 283 pitches. During his last 57 innings in 1962, he recorded 110 strikeouts, 11 walks, and a 0.11 ERA.

Dalkowski was invited to major league spring training in 1963, and the Orioles anticipated promoting him to the majors. However, on March 23, while pitching in relief against the New York Yankees, Dalkowski suffered a career-altering elbow injury. Most accounts state he felt a pop in his left elbow while throwing a slider to Phil Linz, which was diagnosed as a severe muscle strain. Other sources suggest the injury occurred when he damaged his elbow throwing to first base after fielding a bunt from Yankees pitcher Jim Bouton. Regardless of the exact cause, his arm never fully recovered.

2.5. Later Minor League Career and Retirement

When Dalkowski returned to play in 1964, his fastball velocity had significantly decreased to approximately 90 mph. Midway through the season, the Orioles released him. He subsequently played for two more seasons with the minor league affiliates of the Pittsburgh Pirates and Los Angeles Angels, and even returned briefly to the Orioles' farm system. However, he was unable to regain his previous form and ultimately retired from professional baseball in 1966.

2.6. Career Statistics

Dalkowski's minor league career spanned nine seasons. His overall statistics reflect his dominant strikeout ability combined with his notorious lack of control.

| Year | Team | League | Class | Games | Innings Pitched | Hits | Walks | Strikeouts | Wins | Losses | ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | Kingsport | Appalachian | D | 15 | 62 | 22 | 129 | 121 | 1 | 8 | 8.13 |

| 1958 | Knoxville | South Atlantic | A | 11 | 42 | 17 | 95 | 82 | 1 | 4 | 7.93 |

| Wilson | Carolina | B | 8 | 14 | 7 | 38 | 29 | 0 | 1 | 12.21 | |

| Aberdeen | Northern | C | 11 | 62 | 29 | 112 | 121 | 3 | 5 | 6.39 | |

| 1959 | Aberdeen | Northern | C | 12 | 59 | 30 | 110 | 99 | 4 | 3 | 5.64 |

| Pensacola | Alabama-Florida | D | 7 | 25 | 11 | 80 | 43 | 0 | 4 | 12.96 | |

| 1960 | Stockton | California | C | 32 | 170 | 105 | 262 | 262 | 7 | 15 | 5.14 |

| 1961 | Kennewick | Northwest | B | 31 | 103 | 75 | 196 | 150 | 3 | 12 | 8.39 |

| 1962 | Elmira | Eastern | A | 31 | 160 | 117 | 114 | 192 | 7 | 10 | 3.04 |

| 1963 | Elmira | Eastern | AA | 13 | 29 | 20 | 26 | 28 | 2 | 2 | 2.79 |

| Rochester | International | AAA | 12 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 6.00 | |

| 1964 | Elmira | Eastern | AA | 8 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 6.00 |

| Stockton | California | A | 20 | 108 | 91 | 62 | 141 | 8 | 4 | 2.83 | |

| Columbus | International | AAA | 3 | 12 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 8.25 | |

| 1965 | Kennewick | Northwest | A | 16 | 84 | 84 | 52 | 62 | 6 | 5 | 5.14 |

| San Jose | California | A | 6 | 38 | 35 | 34 | 33 | 2 | 3 | 4.74 | |

| Career Total | 236 | 995 | 682 | 1,354 | 1,396 | 46 | 80 | 5.57 |

In his nine minor league seasons, Dalkowski compiled a lifetime win-loss record of 46-80 and an ERA of 5.57. He recorded 1,396 strikeouts and issued 1,354 walks in 995 innings pitched, a near one-to-one ratio that underscores his unique pitching profile.

3. Life After Baseball

After his baseball career, Stephen Dalkowski faced significant personal challenges, particularly with alcohol abuse and its lasting health consequences.

3.1. Personal Struggles and Health Issues

In 1965, Dalkowski married Linda Moore, a schoolteacher, in Bakersfield, California, but they divorced two years later. Unable to find stable employment, he became a migrant worker. Dalkowski struggled severely with alcohol abuse, which had been present during his playing career but escalated significantly after his retirement. His drinking often led to violent behavior and frequent arrests. He experienced economic hardship, living penniless in a small apartment in California by the end of the 1980s. At some point, he married a motel clerk named Virginia, who moved him to Oklahoma City in 1993. Virginia died of a brain aneurysm in 1994.

Dalkowski's prolonged alcohol abuse ultimately led to the onset of alcohol-induced dementia. By 2003, he stated in an interview that he was unable to remember life events that occurred between 1964 and 1994, indicating a significant period of memory loss.

3.2. Rehabilitation Efforts and Later Years

The Association of Professional Ball Players of America (APBPA) provided Dalkowski with periodic assistance from 1974 to 1992, during which he underwent rehabilitation attempts. For several months at a time, he managed to find work and maintain sobriety. However, he would consistently relapse into heavy drinking, leading the APBPA to eventually cease financial support after discovering he was using funds to purchase alcohol.

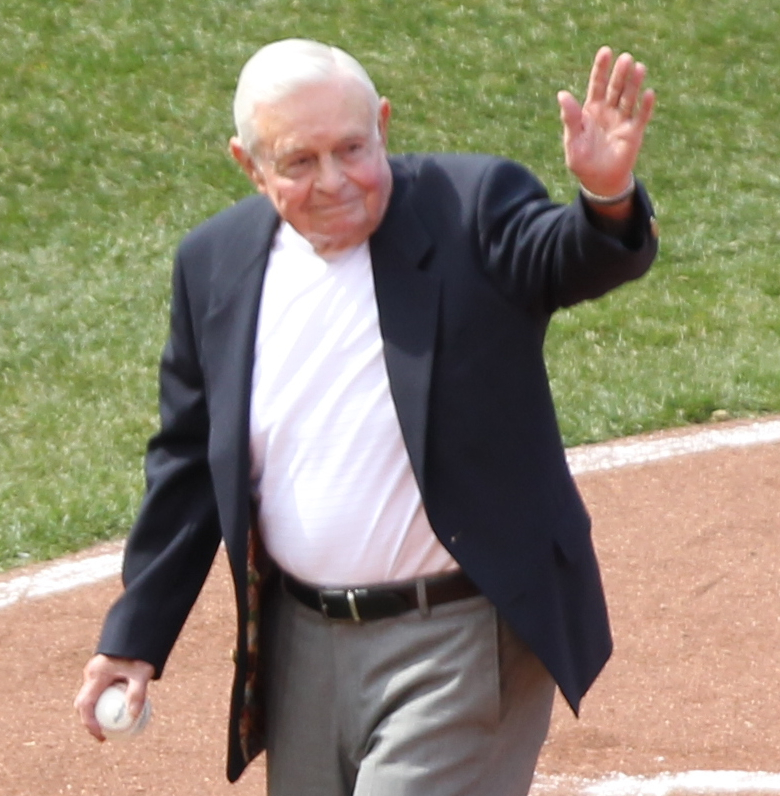

After his second wife's death, Dalkowski was moved to his birthplace of New Britain, Connecticut, by his relatives and former teammate Frank Zuppo, who had caught Dalkowski's pitches in Stockton in 1960. He resided for several years at a long-term care facility in New Britain, the Walnut Hill Care Center. Although his health had significantly deteriorated, he showed signs of recovery and maintained sobriety in his later years despite the lasting effects of his alcohol dependence. He was able to attend baseball games and spend time with his family. On September 8, 2003, Dalkowski returned to a baseball mound to throw a ceremonial first pitch to relief pitcher Buddy Groom at an Orioles-Mariners game.

4. Legacy and Evaluation

Stephen Dalkowski's extraordinary talent and tumultuous life have secured him a unique and enduring place in baseball history and popular culture, despite his never having played in the major leagues.

4.1. Influence on Popular Culture

Dalkowski's life and incredible pitching abilities have inspired characters in notable films. Screenwriter and film director Ron Shelton, who played in the Baltimore Orioles minor league organization shortly after Dalkowski, based the character Ebby Calvin "Nuke" LaLoosh (played by Tim Robbins) in his 1988 film Bull Durham loosely on the tales he heard about Dalkowski. Additionally, Brendan Fraser's character in the 1994 film The Scout is also said to be loosely based on Dalkowski. These cinematic portrayals highlight his enduring presence in popular narratives and his transition from a baseball curiosity to a cultural archetype.

4.2. Place in Baseball History and Recognition

Despite never reaching the major leagues and concluding his minor league career in Class-B ball, Dalkowski attained a unique status as a "living legend." A 1966 Sporting News item about the end of his career was famously headlined "Living Legend Released." His contributions to baseball lore were formally recognized with his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals on July 19, 2009.

In a 1970 profile of Dalkowski, Sports Illustrated's Pat Jordan eloquently summarized his career: "Inevitably, the stories outgrew the man, until it was no longer possible to distinguish fact from fiction. But, no matter how embellished, one fact always remained: Dalkowski struck out more batters and walked more batters per nine-inning game than any professional pitcher in baseball history." Jordan concluded, "His failure was not one of deficiency, but rather of excess. He was too fast. His ball moved too much. His talent was too superhuman... It mattered only that once, just once, Steve Dalkowski threw a fastball so hard that Ted Williams never even saw it. No one else could claim that." Hall of Fame pitcher "Sudden" Sam McDowell, considered one of the fastest MLB pitchers of the 1960s, wrote in the foreword to Dalkowski's 2020 biography, Dalko: The Untold Story of Baseball's Fastest Pitcher: "I truly believe he threw a lot harder than I did! It's likely he delivered the fastest pitch I ever saw!"

4.3. Critical Perspectives and Unfulfilled Potential

Stephen Dalkowski's career serves as a compelling case study of raw, unpredictable talent and unfulfilled potential. His immense velocity, while awe-inspiring, was consistently undermined by a profound inability to control his pitches. This volatile combination made him a fearsome opponent but also an unreliable one.

His personal struggles with alcoholism and violent behavior off the field undoubtedly compounded his on-field issues, impacting his ability to develop consistent command and maintain a stable career path. Earl Weaver's attempts to simplify Dalkowski's approach, based on his perceived lower IQ, illustrate the depth of the challenges Dalkowski faced in harnessing his physical gifts. The career-ending elbow injury in 1963, just as he seemed on the cusp of a major league call-up, remains a poignant moment of "what if" in baseball history, forever cementing his status as a legendary figure who, for a confluence of reasons, never reached the game's highest level.

5. Death

Stephen Dalkowski's life concluded in April 2020.

5.1. Circumstances of Death

Stephen Dalkowski died on April 19, 2020, in New Britain, Connecticut, at the age of 80. His passing was due to complications from dementia and COVID-19, making him one of the many nursing home victims who succumbed to the virus during the COVID-19 pandemic in Connecticut.