1. Overview

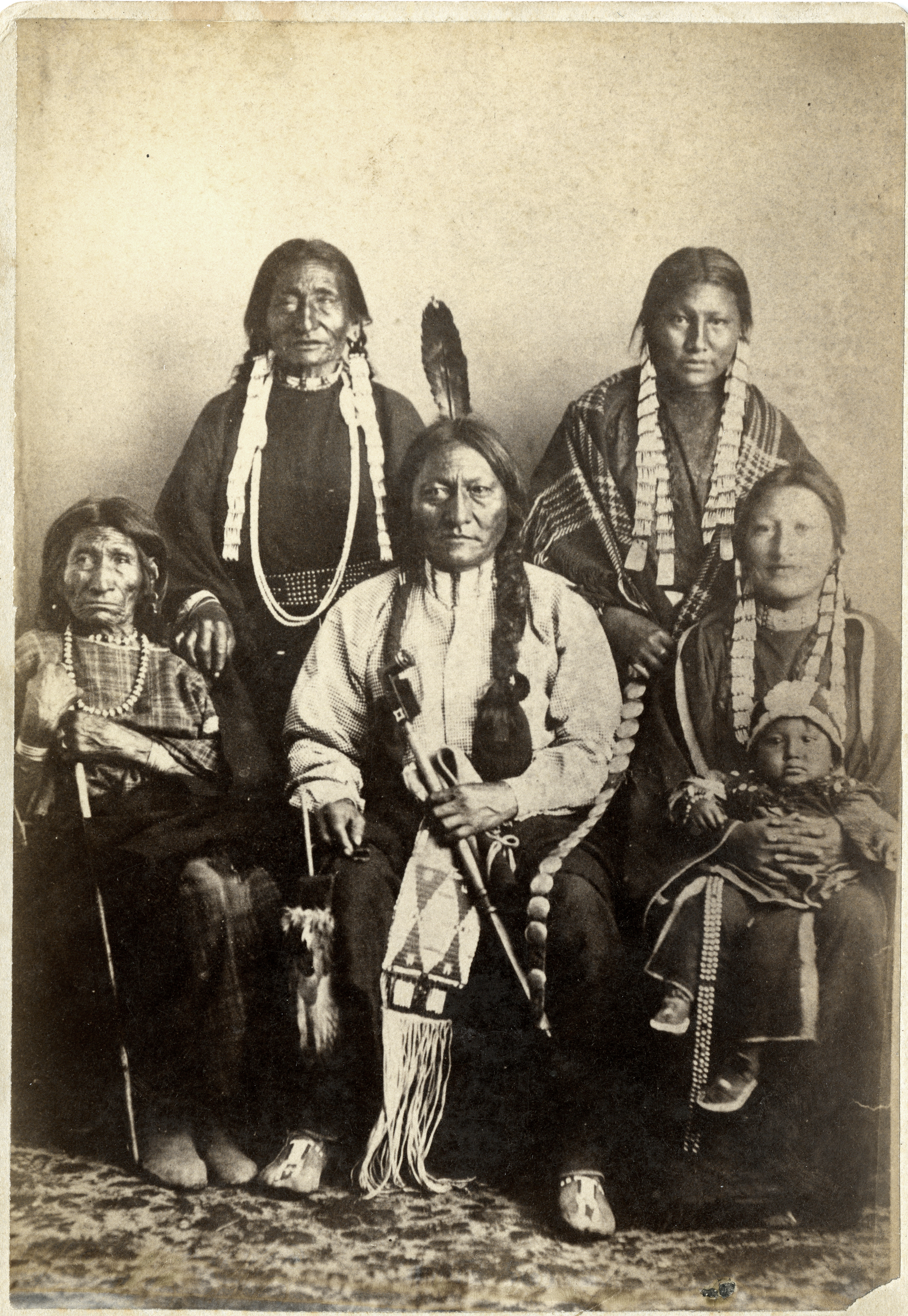

Sitting Bull, known in his native Lakota as Tȟatȟáŋka ÍyotakeTatanka Iyotake (Sitting Bull)lkt, was a prominent Hunkpapa Lakota leader who spearheaded his people's resistance against the encroaching policies of the United States government during the latter half of the 19th century. Born around 1831-1837, he rose to become a revered holy man and a symbol of Indigenous resilience, advocating for the preservation of Native American lands and cultural sovereignty against the tide of US expansionism. His life was marked by continuous struggle against the violation of treaties and the forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples, a period characterized by significant injustices and human rights abuses against Native American communities.

Sitting Bull gained international renown for his spiritual leadership in the Great Sioux War of 1876, particularly his prophetic vision before the decisive Battle of the Little Bighorn, where the Lakota and Cheyenne forces achieved a remarkable victory over Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry. This triumph, however, led to intensified military campaigns by the US, forcing Sitting Bull and his followers into exile in Canada. Upon his eventual surrender and return to the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, he continued to challenge government policies, including land cessions and the suppression of Indigenous spiritual movements like the Ghost Dance. His unwavering commitment to his people's rights ultimately led to his tragic death on December 15, 1890, during an arrest attempt by Indian agency police. Sitting Bull's legacy endures as a powerful icon of resistance, cultural pride, and the ongoing fight for Indigenous self-determination.

2. Early Life and Background

Sitting Bull was born on land that would later become part of the Dakota Territory, between 1831 and 1837. Family oral tradition, as asserted by his great-grandson, places his birth along the Yellowstone River, south of present-day Miles City, Montana. At birth, he was named Ȟoká PsíčeHoka Psice (Jumping Badger)lkt. Due to his thoughtful and unhurried nature, he was given the nickname HúŋkešniHunkešni (Slow)lkt. He was the only male child among his siblings, with his eldest sister, Pretty Feather, often carrying him on horseback in a travois (a type of sled) and singing him warrior songs. Even as a baby, he showed fearlessness, once delighting in a runaway dog pulling his child's carriage. His early boldness was recognized by his father, Jumping Bull (also known as Returns Again), and his uncle, Four Horns, who foresaw his future greatness.

His father, a medicine man and skilled hunter, communicated with animals. Once, while camping with three warriors, a buffalo approached their campfire and repeated four names: "Sitting Bull, Jumping Bull, Bull Standing with Cow, and Lonely Bull." Jumping Bull understood this as the buffalo offering new names, and he chose "Tatanka Iyotake" (Sitting Bull), which he later bestowed upon his son.

As a child, Húŋkešni was trained as a warrior by his father, learning to be ready with his arrows at any moment. At eight, his father tested him by having his uncle mimic a wolf's howl and shake bushes to scare him, but Húŋkešni remained unfazed. His father, a respected warrior adorned with an eagle feather warbonnet and many horses, held a "give-away" feast to celebrate his son, presenting him with a powerful bow and arrows. At age 10, Húŋkešni successfully hunted his first buffalo. At 12, during a buffalo hunt, a calf charged him; he bravely grabbed its horns, jumped on its back, and rode it, leading his father to host another celebratory feast.

At 14, he received a "coup stick," a weapon used in the honorable Plains Indian practice of "counting coup," where warriors gained prestige by touching or striking an enemy in battle without killing them. During a raid against the rival Crow Nation, Húŋkešni secretly followed a party of 20 warriors. In the midst of battle, he bravely charged forward, touched a Crow warrior who was about to shoot an arrow, and then retreated. Upon his return, his father, overjoyed by his son's valor, declared, "My son has struck the enemy. My son is brave! From now on, his name will be Tatanka Iyotake!" He presented his son with an eagle feather, a warrior's horse, and a hardened buffalo hide shield, marking his passage into manhood. His father was thereafter known as Jumping Bull.

In 1847, at 15, Sitting Bull participated in a horse-stealing raid on a Crow village. While returning with a large number of horses, they were pursued by Crow warriors. In a shootout, Sitting Bull dismounted and engaged an enemy warrior, sustaining a gunshot wound to his left hip, which caused a lifelong limp. He killed the Crow warrior with a knife. At 17, he performed an act of mercy, killing a captive Crow woman with an arrow before she could be burned alive by Hunkpapa women. Though not considered handsome, his polite and kind demeanor made him popular among women, and he eventually had nine wives.

Sitting Bull also developed his spiritual abilities. During a rest on a hunt, he dreamt of a grizzly bear approaching him, with a woodpecker whispering to him to play dead. He awoke to find both the bear and woodpecker present. Following the dream's guidance, he remained still, and the bear eventually wandered away. The woodpecker then told him that he, who could speak with "bird people," would become a great figure for his tribe. He followed the woodpecker's instructions, shot the bear in the center of its four legs, and killed it, taking its claws for a necklace. From then on, his eagle feather warbonnet and bear claw necklace became his most prized possessions. He also heard voices from a high rock mountain in the Black Hills, interpreting the presence of an eagle there as a prophecy of his future as a great warrior. A wounded wolf once came to him, promising greatness if he helped it; Sitting Bull removed its arrow and tended its wounds.

As a young man, Sitting Bull earned a reputation as a courageous warrior, joining the Akicita (police) and Tokala (Kit Fox Warrior Society). At 25, he became the bravest warrior of the Cante Tinsza (Strong Heart Warrior Society), earning the honor of wearing a long red sash, which he would pin to the ground with an arrow in battle, vowing to fight until help arrived. He excelled in hunting and counting coup, and his quiet, humorous storytelling made him beloved by his peers. He was also a skilled Wičháša WakȟáŋWichasha Wakan (medicine man)lkt, proficient in various healing and spiritual practices, aiding his people. He was often compared to a buffalo, "stubborn, fearless, unyielding, never fleeing even in a winter blizzard, always moving against the wind."

3. Resistance and Conflict with the United States

The expanding US colonization crossed the Mississippi River in the 1860s, reaching the Great Plains where the Sioux resided. All Indigenous tribes faced extermination or confinement to Indian reservations, their territories forcibly seized by military might. Sitting Bull learned of the harsh conditions on reservations from his Dakota Sioux kin, who had been forcibly relocated after the Dakota War of 1862. This conflict, triggered by the starvation of the Dakota people due to broken US promises, resulted in the killing of 300 to 800 settlers and soldiers in south-central Minnesota. Despite the American Civil War, the United States Army retaliated in 1863 and 1864, even against bands not involved in the hostilities, pursuing a policy of "Sioux extermination."

In June 1863, the US Army conducted a military expedition into the west in response to the Dakota Uprising, marking the first direct conflict between Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa Lakota and the WašíčuWashichu (white people)lkt. Although his people were Lakota, not Dakota, they were attacked as part of the broader US policy against the Sioux. In July 1864, Brigadier General Alfred Sully's US cavalry attacked a combined force of Santee Sioux (Dakota) and Teton Sioux (Lakota) at Killdeer Mountain. Sitting Bull, along with Gall of the Lakota and Inkpaduta of the Dakota, led the defense. During this battle, Sitting Bull resolved to keep his people away from the white world and never sign any unjust treaties. On September 2, he was shot in the left hip during an attack on a white wagon train near present-day Marmarth, North Dakota. The bullet exited his lower back, and the wound was not serious.

The Hunkpapa and other Sioux bands fiercely resisted white incursions, becoming targets for extermination by the US. Sitting Bull's prominent role in these conflicts earned him respect from both his people and the white observers. By 1866, he was recognized as a leading warrior of the Northern Plains, alongside Crazy Horse of the Oglala Lakota. He distinguished himself in what white people called Red Cloud's War, a conflict between the US Army and the Sioux and Cheyenne. By 1867, he had become a central warrior of the Cante Tinsza (Strong Heart Warrior Society). He famously stated, "The old warriors are gone. I myself will show courage." Sitting Bull later articulated his understanding of a warrior to white people: "For us, a warrior is not just one who fights. Since no one has the right to take another's life, a warrior is one who sacrifices for us and for others. Their mission is to care for and protect the elderly, the weak, those who cannot protect themselves, and the children who represent the future."

The US government's approach to Indigenous relations was fundamentally flawed from the outset. Indigenous societies, including the Lakota, operated under a consensus-based democracy, where "chiefs" were primarily "peacemakers" rather than absolute rulers or representatives of the entire tribe. However, white officials mistakenly viewed chiefs as tribal leaders with absolute authority and sought to control the Sioux by entering into treaties with them. Indigenous peoples, with their nature-based worldview, found the capitalist and Christian values of the white settlers incompatible with their own. The US soon resorted to overwhelming military force to seize Sioux territory.

While leaders like Red Cloud and Spotted Tail engaged with US forts and agencies for provisions, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse refused to participate in the white peace commissions. The majority of the Sioux sided with Sitting Bull, as their society, like other Plains Indians, was highly individualistic, and those who gathered around Sitting Bull did so out of free will. However, the US government misinterpreted this as a unified rebellion led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, viewing them as the primary instigators of resistance in the Western Indian Wars.

3.1. Red Cloud's War

From 1866 to 1868, Red Cloud, a leader of the Oglala Lakota, led a war against US forces, attacking their forts to maintain control over the Powder River Country in present-day Montana. In support of Red Cloud, Sitting Bull led numerous war parties against Fort Berthold, Fort Stevenson, and Fort Buford, and their allies, from 1865 through 1868. This period of conflict became known as Red Cloud's War.

By early 1868, the US government sought a peaceful resolution. It agreed to Red Cloud's demands to abandon Fort Phil Kearny and Fort C.F. Smith. Gall of the Hunkpapa and representatives from the Hunkpapa, Sihasapa (Blackfeet), and Yankton Dakota signed a version of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) on July 2, 1868, at Fort Rice near Bismarck, North Dakota. This treaty established the Great Sioux Reservation, centered in South Dakota, recognizing it as inviolable Indigenous territory. However, Sitting Bull refused to sign or acknowledge the treaty. He famously told Jesuit missionary Pierre Jean De Smet, who sought him on behalf of the government, "I wish all to know that I do not propose to sell any part of my country... I love the small oak forest. I like to see the oak trees, and I respect them. They endure the summer heat and winter cold, growing and flourishing just like us." He continued his hit-and-run attacks on forts in the upper Missouri area throughout the late 1860s and early 1870s.

The events between 1866 and 1868 are a debated period in Sitting Bull's life. While historian Stanley Vestal, based on 1930 interviews with surviving Hunkpapa, claimed Sitting Bull was made "Supreme Chief of the whole Sioux Nation" at this time, later historians and ethnologists refuted this. They argue that Lakota society was highly decentralized, with bands and elders making individual decisions, including whether to wage war.

3.2. The Black Hills Gold Rush and the Great Sioux War

Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa band continued to attack migrating parties and forts in the late 1860s. In 1871, the Northern Pacific Railway began surveying a route across the northern plains directly through Hunkpapa lands, encountering fierce Lakota resistance. The railway surveyors returned the following year with federal troops, but Sitting Bull and the Hunkpapa attacked the party, forcing them to retreat. In 1873, the military escort for the surveyors was further increased, but Sitting Bull's forces resisted the survey "most vigorously." The Panic of 1873 forced the railway's backers, including Jay Cooke, into bankruptcy, halting construction through Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota territory.

Following the 1848 discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada, the potential for gold mining in the Black Hills attracted significant interest. In 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition from Fort Abraham Lincoln near Bismarck, North Dakota, to explore the Black Hills for gold and identify a suitable fort location. Custer's announcement of gold triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush, escalating tensions between the Lakota and European Americans seeking to settle the Black Hills.

Although Sitting Bull did not attack Custer's 1874 expedition, the US government faced increasing pressure to open the Black Hills for mining and settlement. After failed negotiations to purchase or lease the Hills, the government sought ways to circumvent the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which promised to protect the Sioux in their land. They were alarmed by reports of Sioux depredations, some of which were encouraged by Sitting Bull. In November 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered all Sioux bands outside the Great Sioux Reservation to move onto the reservation, knowing many would not comply. By February 1, 1876, the Interior Department declared as "hostile" those bands living off the reservation, providing the military with a pretext to pursue Sitting Bull and other Lakota bands.

Historian Margot Liberty, based on tribal oral histories, suggests that many Lakota bands allied with the Cheyenne during the Plains Wars due to the perception that the Cheyenne were under attack by the US. She theorizes that the major conflict should have been called "The Great Cheyenne War," as the Northern Cheyenne had led several battles among the Plains Indians and suffered more US Army camp destructions than any other nation before 1876. However, other historians, such as Robert M. Utley and Jerome Greene, also using Lakota oral testimony, concluded that the Lakota coalition, with Sitting Bull as a prominent figure, was the primary target of the federal government's pacification campaign. This conflict became known as the Great Sioux War.

During 1868-1876, Sitting Bull emerged as one of the most significant Native American political leaders. After the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie and the establishment of the Great Sioux Reservation, many traditional Sioux warriors, like Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, moved onto reservations, becoming dependent on US Indian agencies for subsistence. Other chiefs, including members of Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa band such as Gall, also temporarily lived at agencies, needing supplies as white encroachment and buffalo herd depletion reduced their resources and challenged Indigenous independence. Sitting Bull's refusal to rely on the US government meant he and his small band often lived in isolation on the Great Plains. When Native Americans were threatened by the United States, numerous members from various Sioux bands and other tribes, like the Northern Cheyenne, joined Sitting Bull's camp. His reputation for "strong medicine" grew as he continued to evade the European Americans.

4. The Battle of the Little Bighorn and Exile

In 1875, the Northern Cheyenne, Hunkpapa, Oglala, Sans Arc, and Minneconjou gathered for a Sun Dance, with both the Cheyenne medicine man White Bull (or Ice) and Sitting Bull participating. This ceremonial alliance preceded their unified fight in 1876. Sitting Bull experienced a major revelation during this ceremony.

4.1. Sun Dance and Vision

As the invading US forces approached, a large gathering of Sioux held the Sun Dance. Sitting Bull, then 45 years old, volunteered to be a Sun Dancer, fasting and dancing for four days while gazing at the sun. He made a "piercing vow," and on the fourth day, underwent the "piercing ceremony," where eagle claws were pierced through the flesh of his chest and arms, connecting him to a sacred pole with rawhide thongs. His adoptive brother, Jumping Bull (Tatanka Psicha), whom he had taken in from the Assiniboine tribe years earlier, assisted in this ritual.

During this piercing ceremony, Sitting Bull received a powerful vision: he saw WašíčuWashichu (white soldiers)lkt in blue coats falling upside down into the Lakota camp. He declared, "The Great Spirit has given our enemies to us. We are to destroy them. We do not know who they are. They may be soldiers." He also warned his people not to take the soldiers' guns or horses as spoils, stating that desiring white people's possessions would bring a curse upon the Indigenous people. After the Sun Dance, the large encampment of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho moved to the Greasy Grass River (Little Bighorn River), where they established a council tipi to discuss their strategy against the white invaders.

4.2. Battle of the Little Bighorn

Following the ultimatum on January 1, 1876, which declared Sioux and others living off the reservation as "hostiles," Native Americans flocked to Sitting Bull's camp. He actively encouraged this "unity camp," sending scouts to reservations to recruit warriors and instructing the Hunkpapa to share supplies with newcomers. For example, he provided for Wooden Leg's Northern Cheyenne tribe, who had been impoverished by Captain Reynolds' attack on March 17, 1876, and sought refuge in Sitting Bull's camp.

Throughout the first half of 1876, Sitting Bull's camp continuously expanded, attracting warriors and families seeking safety in numbers. This created an extensive village estimated at over 10,000 people. On June 25, 1876, Custer's scouts discovered this massive encampment along the Little Bighorn River. Sitting Bull did not take a direct military role in the ensuing battle; instead, he acted as a spiritual leader, having performed the Sun Dance just a week prior.

After receiving orders to attack, Custer's 7th Cavalry troops quickly lost ground and were forced to retreat. Sitting Bull's followers, led into battle by Crazy Horse and Gall, counterattacked. The Native American forces, including Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho warriors, decisively defeated Custer's battalion, annihilating them, while surrounding and laying siege to the other two battalions led by Major Reno and Captain Benteen. This victory, where Custer and his entire command were killed, seemed to fulfill Sitting Bull's prophetic vision. However, his warning against taking spoils was largely ignored; by nightfall, the Indigenous warriors had collected saddles, uniforms, pistols, carbines, and 10,000 rounds of ammunition from the cavalry.

4.3. Exile in Canada

The Native Americans' victory celebrations were short-lived. Public shock and outrage at Custer's defeat and death, coupled with the government's realization of the remaining Sioux's military capability, prompted the Department of War to deploy thousands more soldiers to the area. Over the next year, the reinforced American military pursued the Lakota, forcing many Native Americans to surrender. Sitting Bull, however, refused. In May 1877, he led his band across the border into the North-West Territories (now Saskatchewan), Canada, seeking freedom. He remained in exile for four years near Wood Mountain, refusing a pardon and the chance to return.

Upon crossing into Canadian territory, Sitting Bull was met by the Mounties. James Morrow Walsh, commander of the North-West Mounted Police, explained that the Lakota were now on British soil and must obey British law. Walsh emphasized that he enforced the law equally and that every person in the territory had a right to justice. Walsh became an advocate for Sitting Bull, and the two developed a strong friendship that lasted the rest of their lives.

While in Canada, Sitting Bull also met with Crowfoot, a leader of the Blackfoot Confederacy, who were long-standing enemies of the Lakota and Cheyenne. Sitting Bull sought to make peace with the Blackfeet Nation, and Crowfoot, himself an advocate for peace, eagerly accepted the tobacco peace offering. Sitting Bull was so impressed by Crowfoot that he named one of his sons after him.

Sitting Bull and his people stayed in Canada for four years. However, due to the smaller size of the buffalo herds in Canada, finding enough food to feed his starving people became increasingly difficult. Sitting Bull's presence in Canada also heightened tensions between the Canadian and United States governments, with the US continuously demanding his extradition. Before leaving Canada, Sitting Bull may have visited Walsh for a final time, leaving a ceremonial headdress as a memento.

5. Surrender and Life on the Reservation

5.1. Return and Surrender

Hunger and desperation eventually compelled Sitting Bull and 186 of his family and followers to return to the United States and surrender on July 19, 1881. At Fort Buford, Sitting Bull's young son, Crow Foot, surrendered his Winchester Rifle to Major David H. Brotherton, the commanding officer. Sitting Bull famously declared to Brotherton, "I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender my rifle." The next day, in a small ceremony at the Commanding Officer's Quarters, attended by four soldiers, 20 warriors, and other guests, Sitting Bull expressed his desire to view soldiers and white people as friends, but he questioned who would teach his son the new ways of the world, indicating his wish for his son to learn English literacy. Two weeks later, after waiting in vain for other tribal members to follow him from Canada, Sitting Bull and his band were transferred to Fort Yates, the military post adjacent to the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, which straddles the present-day boundary between North and South Dakota.

Sitting Bull and his band of 186 people were kept separate from other Hunkpapa gathered at the agency. US Army officials feared he would incite trouble among the recently surrendered northern bands. On August 26, 1881, US census taker William T. Selwyn visited him, counting 12 people in Sitting Bull's immediate family and recording 41 families, totaling 195 people, in his band. The military decided to transfer Sitting Bull and his band to Fort Randall to be held as prisoners of war. Loaded onto a steamboat, the band of 172 people was sent down the Missouri River to Fort Randall near present-day Pickstown, South Dakota, on the southern border of the state, where they spent the next 20 months. They were finally allowed to return north to the Standing Rock Agency in May 1883.

5.2. Life at Standing Rock

In 1883, Sitting Bull was transferred to the Standing Rock Agency, located 317 mile (510 km) northwest along the Missouri River. The supervisor of this reservation was James McLaughlin, a man with a mixed-race Sioux wife, who was deeply wary of Sitting Bull's influence. McLaughlin frequently interfered in Sitting Bull's life, even demanding that he divorce one of his two wives. Sitting Bull retorted, "If you insist, you should go to each of my wives and tell them directly." In Indigenous societies, marriage and divorce were considered matters of individual freedom.

With Sitting Bull disarmed and confined to the reservation, white society began to treat him as a celebrity. Mistakenly believing him to be the "Great Leader of all Sioux," they exploited him as a spectacle, much as they did with Geronimo of the Apache.

The US government's policies towards Indigenous peoples were based on fundamental misunderstandings. Indigenous societies are inherently democratic and consensus-based; a "chief" is merely a "peacemaker" within the tribe, not an absolute ruler. However, white officials misinterpreted "chiefs" as tribal leaders and sought to control the Sioux through treaties with them.

In 1883, The New York Times reported that Sitting Bull had been baptized into the Catholic Church. However, James McLaughlin, the Indian agent at Standing Rock Agency, dismissed these reports, stating, "The reported baptism of Sitting-Bull is erroneous. There is no immediate prospect of such ceremony so far as I am aware."

6. Cultural and Public Engagements

6.1. Meeting Annie Oakley

In September 1884, show promoter Alvaren Allen sought permission from Agent James McLaughlin for Sitting Bull to tour parts of Canada and the northern United States in a show called the "Sitting Bull Connection." It was during this tour that Sitting Bull met Annie Oakley in present-day Minnesota. He was profoundly impressed by Oakley's sharpshooting skills, offering 65 USD (equivalent to approximately 2.20 K USD in 2024) for a photographer to capture a picture of them together.

The admiration was mutual. Oakley stated that Sitting Bull made a "great pet" of her. Observing Oakley's modest attire, deep respect for others, and remarkable stage presence despite her height of only five feet, Sitting Bull believed she was "gifted" by supernatural means to shoot so accurately with both hands. As a result of his esteem, he symbolically "adopted" her as a daughter in 1884, naming her "Little Sure Shot," a moniker Oakley used throughout her career.

6.2. Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show

In 1885, Sitting Bull was allowed to leave the reservation to join Buffalo Bill Cody's Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. He earned about 50 USD a week (equivalent to approximately 1.70 K USD in 2024) for riding once around the arena, where he was a popular attraction. While it is rumored that he cursed his audiences in his native tongue during the show, historian Robert M. Utley contends that he did not. Historians have reported that Sitting Bull gave speeches about his desire for education for the young and for reconciliation between the Sioux and whites.

However, historian Edward Lazarus wrote that Sitting Bull reportedly cursed his audience in Lakota in 1884 during an opening address celebrating the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway. According to Michael Hiltzik, Sitting Bull declared in Lakota, "I hate all White people. You are thieves and liars. You have taken away our land and made us outcasts." The translator, however, read the original address, which had been written as a "gracious act of amity," leaving the audience, including President Ulysses S. Grant, none the wiser.

Sitting Bull remained with the show for four months before returning home. During that time, audiences considered him a celebrity and romanticized him as a warrior. He earned a small fortune by charging for his autograph and picture, though he often gave his money away to the homeless and beggars. When he retired from the show, Cody gifted him a gray horse and a sombrero.

In 1887, Buffalo Bill invited him to accompany the show to London for Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee. Sitting Bull declined this opportunity to meet the "Great Mother" (as white people called the British Queen, contrasting with the US President as "Great Father"), stating, "It is not good for our cause for me to travel around. I have much to do here. I have much to say about our land."

The US government again broke its treaties, attempting to purchase 15 K mile2 (40.00 K km2) of Sioux reservation land in western Dakota at an astonishingly low price of 0.5 USD per 1.5 K mile2 (4.00 K km2). By this time, the buffalo, their primary food source, had been nearly exterminated by white hunters, a deliberate strategy to subdue Indigenous populations. Sitting Bull strongly opposed this proposal and persuaded other reservation Sioux to reject it. The US planned to resell the land to white settlers for 25 USD per 1.5 K mile2 (4.00 K km2).

In August 1888, government officials arrived at the Standing Rock Agency to negotiate the land purchase. At Fort Yates, Sitting Bull passionately debated before the US representatives, skillfully thwarting their coercive tactics, despite repeated attempts by officials to silence him. Sitting Bull and the chiefs deliberated and ultimately, almost unanimously, refused to sign the land sale agreement.

On October 15, 1888, a delegation of 60 Sioux representatives, including Sitting Bull, met with Secretary of the Interior William Vilas in Washington, D.C., under the guidance of Agent James McLaughlin. The US raised its offer to 1 USD per 1.5 K mile2 (4.00 K km2), but the Sioux remained unconvinced. Back home, tribal members suffered from hunger due to the agent's negligence and embezzlement of food annuities. In 1889, the US increased the offer to 1.25 USD per 1.5 K mile2 (4.00 K km2) and added a condition based on the Dawes Act, granting each Sioux household head 321 acre (130 ha) of land. To prevent further fraud, the land rights were to be held in trust by the federal government for 25 years. Under these conditions, the Sioux were pressured into signing the land cession agreement. Sitting Bull angrily declared, "Indians? There are no Indians left but me!" This Dawes Act provision, which forcibly applied patrilineal property rules to matrilineal Indigenous societies, caused immense confusion and contributed significantly to the breakdown of Indigenous social structures.

6.3. Meeting Caroline Weldon

Eastern white society offered considerable aid in response to Sitting Bull's pleas regarding his tribe's plight. In the spring of 1889, Caroline Weldon, a white artist from New York City's social circles and a member of the National Indian Defense Association (NIDA), came to the reservation, ostensibly to paint his portrait. Her true intention was to befriend him and bring him to New York to campaign against the US policy of opening Indigenous reservations to white settlement.

Agent James McLaughlin, alarmed by this, prohibited Sitting Bull from leaving the reservation, thwarting Weldon's plan. McLaughlin also spread false rumors that Weldon and Sitting Bull were romantically involved and that she was reading him biographies of Napoleon and Alexander the Great to incite him to rebellion.

While living in Sitting Bull's home, Weldon assisted his two wives with household chores and meals, an act that in Indigenous culture signified a marriage proposal. Sitting Bull, following Indigenous custom, proposed to her, but Weldon misunderstood this as an insult. She left for New York, leaving behind the completed portraits. Months later, after Sitting Bull's assassination, Indian police deliberately slashed her portraits of him with knives.

7. The Ghost Dance Movement and Death

After his time with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency. Tensions between him and Agent McLaughlin intensified, particularly over the division and sale of parts of the Great Sioux Reservation. During a period of harsh winters and prolonged droughts affecting the Sioux Reservation, a Paiute Indian named Wovoka initiated a religious movement from present-day Nevada eastward to the Plains. This movement, known as the Ghost Dance, preached a resurrection of Indigenous ways of life. It called upon Indigenous peoples to dance and chant for the return of deceased relatives and the buffalo. The dance also incorporated "ghost shirts," which were believed to stop bullets. When the movement reached Standing Rock, Sitting Bull allowed the dancers to gather at his camp. Although he did not actively participate in the dancing, he was perceived as a key instigator, causing alarm in nearby white settlements.

7.1. Involvement in the Ghost Dance

Around this time, Sitting Bull revisited the rock mountain where he had received a prophecy from an eagle. At the summit, a meadowlark appeared, telling him, "You will be killed by a Sioux."

Kicking Bear (Mato Wanataka), a Sioux, left the reservation to meet Wovoka, was deeply impressed by his teachings, and spread the Ghost Dance among the Sioux. The Ghost Dance quickly gained popularity among the Sioux, who added the belief that "ghost shirts" would make them impervious to white bullets. Sitting Bull, however, did not fully believe this specific doctrine. Although he tried the Ghost Dance himself, he reportedly told Kicking Bear, "The dead will not rise."

Agent James McLaughlin, however, grew highly concerned by the doctrine of bullet-proof shirts. He mistakenly believed that Sitting Bull was the ringleader of the Ghost Dance and reported this to the government, ordering Sitting Bull to stop the rituals. Sitting Bull responded to McLaughlin's demand: "Then I will go with you to the tribes that spread this dance. And finally, we will go to the tribe that started this dance. If they cannot summon the savior and the dead do not rise, then I will return and tell the Sioux that it was all a lie. If you truly see the savior, then you should let the dance continue."

McLaughlin dismissed this as a pretense and remained convinced that Sitting Bull was the primary instigator of the religious movement. McLaughlin reported to the government: "As far as the Standing Rock Reservation is concerned, this religion has been exploited by Sitting Bull from the beginning. He has lost his former influence over the Sioux, so he brought this in and tried to use it to regain tribal leadership. That way, he could safely lead the tribe into any heinous scheme he desired."

As noted, Indigenous societies, including the Sioux, did not have "individual leaders" in the white sense; all decisions were made by consensus. McLaughlin's view was a fundamental misunderstanding of Indigenous culture. However, the problem was that he held the power of life and death over the Indigenous people on the reservation.

Furthermore, Daniel F. Royer, the agent at the Pine Ridge Reservation, viewed the spread of the Ghost Dance as a prelude to a Sioux rebellion. In mid-November 1890, he telegraphed the US government, reporting that "Indians are dancing wildly in the snow and becoming ferocious; we need protection immediately."

In response to reports from Royer and McLaughlin, the US government issued orders to American military forces at various Indian reservations to "be vigilant to suppress any rebellion." Seeing thousands of American soldiers gathering at the forts, the Sioux felt an impending massacre. Many tribal members began to flee from within the designated distance of the agency, seeking refuge in the Makosika (Badlands), a rocky mountain region east of the Black Hills. The US military considered these escapees from the reservation as enemies and dispatched forces to capture them. Sitting Bull remained near the Grand River, but white authorities concluded that the large-scale movement of Indigenous peoples was instigated by him.

7.2. Arrest and Death

White authorities were determined to arrest Sitting Bull as an "instigator," leading to a dispute between the military and civilian officials over who had the right to apprehend him. General Nelson A. Miles, who disdained civilian Indian agents, planned to lure Sitting Bull to the fort using his old friend, Buffalo Bill Cody. However, McLaughlin, angered by being overlooked, intervened with the federal government to block Miles' plan.

On December 14, 1890, McLaughlin, hearing that Sitting Bull might visit the Pine Ridge Reservation agency to the south of Standing Rock, saw it as a prime opportunity for his arrest. He obtained an arrest warrant based on a false report that Sitting Bull was the "ringleader of the Ghost Dance." To avoid alarming the surrounding Indigenous people, McLaughlin decided to entrust the arrest to Indian police. These "Indian agency police" were Indigenous individuals selected by reservation agents for their obedience. McLaughlin assigned this task to Lieutenant Henry Bull Head (Tȟatȟáŋka PȟáTatanka Pha (Bull Head)lkt).

Around 5:30 a.m. on December 15, 39 police officers and four volunteers surrounded Sitting Bull's house. Bull Head knocked and entered, informing Sitting Bull he was under arrest and leading him outside. Sergeant Shavehead warned him, "If you resist, we will shoot you on the spot." Sitting Bull agreed to cooperate, saying, "Alright, wait while I get dressed," but was forced to dress while being restrained, leading to a struggle. Meanwhile, Sioux people from the surrounding area began to gather. As Sitting Bull was dragged outside, he resolved himself, declaring, "I will not go!"

Hearing Sitting Bull's cry, an enraged Lakota named Catch-the-Bear shouldered his rifle and fired at Bull Head, missing him. Bull Head, despite being severely wounded, fired his revolver into Sitting Bull's chest. Another police officer, Red Tomahawk (Čhaŋȟpí DútaChanhpi Duta (Red Tomahawk)lkt), shot Sitting Bull in the head, and Sitting Bull fell to the ground. Sitting Bull died between 12 and 1 p.m.

A close-quarters fight erupted, and within minutes, several men were dead. The Lakota killed six policemen immediately, and two more died shortly after the fight, including Bull Head. The police killed Sitting Bull and seven of his supporters at the site, along with two horses. Among the dead were Sitting Bull's 17-year-old son, Crow Foot, and his adoptive brother, Jumping Bull.

8. Burial and Remains

Sitting Bull's body was taken to present-day Fort Yates, North Dakota, where it was placed in a coffin made by the United States Army carpenter there, and he was buried on the grounds of Fort Yates. A monument was later installed to mark his burial site after his remains were reportedly taken to South Dakota.

In 1953, Lakota family members exhumed what they believed to be Sitting Bull's remains, transporting them for reinterment near Mobridge, South Dakota, which, according to oral tradition, was near his birthplace. A monument to him was erected there.

9. Legacy and Commemoration

The death of this great warrior, a spiritual pillar of the Sioux, plunged Sioux society into new panic. Bands of Sioux began fleeing their reservations, pursued by the US Army. In this desperate situation, the popularity of the Ghost Dance among the Sioux intensified. One band, devoted to Sitting Bull, traveled 99 mile (160 km) south through a blizzard to join Chief Big Foot (Siha Tanka), Sitting Bull's cousin. The US Army pursued them, leading to the indiscriminate massacre known as the Wounded Knee Massacre.

9.1. Cultural Symbolism

Following Sitting Bull's death, his cabin on the Grand River was transported to Chicago for exhibition at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Indigenous dancers also performed at the exposition. Sitting Bull has become an enduring symbol and archetype of Native American resistance movements, celebrated by descendants of his former enemies. His legacy is one of unwavering defiance against oppression and a powerful source of cultural pride for subsequent generations.

9.2. Representation in Popular Culture

Sitting Bull has been a subject or featured character in numerous Hollywood motion pictures and documentaries, reflecting evolving perceptions of him and Lakota culture in relation to the United States. These include:

- Sitting Bull: The Hostile Sioux Indian Chief (1914)

- Sitting Bull at the Spirit Lake Massacre (1927), with Chief Yowlachie in the title role.

- Annie Oakley (1935), played by Chief Thunderbird.

- Annie Get Your Gun (1950), played by J. Carrol Naish.

- Sitting Bull (1954), with J. Carrol Naish again in the title role.

- Cheyenne (1957), with Frank DeKova as Sitting Bull.

- Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson (1976), played by Frank Kaquitts.

- Crazy Horse (1995), Sitting Bull is played by English, Mohawk and Swiss-German actor August Schellenberg, who stated it was his favorite role.

- Buffalo Girls (1995 miniseries), played by Russell Means.

- Heritage Minute: Sitting Bull (Canadian 60-second short film), played by Graham Greene.

- Into the West (2005 miniseries), played by Eric Schweig.

- Sitting Bull: A Stone in My Heart (2006), a documentary.

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (2007), played by August Schellenberg.

- Woman Walks Ahead (2017), played by Michael Greyeyes.

Sitting Bull is also featured as the leader for the Native American Civilization in the computer game Civilization IV. He is listed as one of 13 great Americans in President Barack Obama's children's book, Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters.

9.3. Commemoration

On September 14, 1989, the United States Postal Service released a Great Americans series 28¢ postage stamp featuring a likeness of the leader. On March 6, 1996, Standing Rock College was renamed Sitting Bull College in his honor. The college serves as an institution of higher education on Sitting Bull's home of Standing Rock in North Dakota and South Dakota.

In August 2010, a research team led by Eske Willerslev, an ancient DNA expert at the University of Copenhagen, announced its intention to sequence the genome of Sitting Bull, with the approval of his descendants, using a hair sample obtained during his lifetime. In October 2021, Willerslev confirmed Lakota writer and activist Ernie Lapointe's contention that he was Sitting Bull's great-grandson and his three sisters were Sitting Bull's biological great-grandchildren.

A 36 ft-tall Lego sculpture of Sitting Bull is displayed at Legoland Billund in Billund, Denmark, the first Legoland park.