1. Early Life and Education

Simon Bradstreet was baptized on March 18, 1603/4, in Horbling, Lincolnshire, England. In the Julian calendar, which was in use in England at the time, the year began on March 25. To avoid confusion with dates in the Gregorian calendar, then in use in other parts of Europe, dates between January and March were often written with both years. He was the second of three sons born to Simon and Margaret Bradstreet. His father served as the rector of the parish church and was descended from minor Irish nobility. Being raised by a vocal Nonconformist father, the young Simon adopted Puritan religious views early in his life.

At the age of 16, Bradstreet began his studies at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he remained for two years. Following this, in 1622, he entered the service of Theophilus Clinton, 4th Earl of Lincoln as an assistant to Thomas Dudley. While some historical accounts suggest Bradstreet returned to Emmanuel College in 1623-1624 to receive an M.A. degree, genealogist Robert Anderson suggests this may have been a different individual. During his time at Emmanuel, Bradstreet was recommended by John Preston to serve as a tutor or governor to Lord Rich, who was the son of Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick. Lord Rich would have been 12 years old in 1623, the year after Preston was appointed master of Emmanuel.

In 1624, Bradstreet took over Dudley's position when Dudley temporarily moved to Boston, Lincolnshire. Upon Dudley's return several years later, Bradstreet briefly served as a steward to the Dowager Countess of Warwick. In 1628, he married Anne Dudley, Thomas Dudley's daughter, when she was 16 years old. That same year, Thomas Dudley and other associates from the Earl of Lincoln's circle established the Massachusetts Bay Company with the aim of founding a Puritan colony in North America. Bradstreet became involved with the company in 1629, and in April 1630, he and his wife, Anne, joined the Dudleys and colonial Governor John Winthrop on the fleet of ships that sailed to Massachusetts Bay. This voyage led to the founding of Boston, which became the capital of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

2. Arrival and Early Colonial Settlements

After a brief stay in Boston, Simon Bradstreet established his first residence in Newtowne, which was later renamed Cambridge, near the Dudley family in what is now Harvard Square. His early years in the colony involved significant political and communal engagement.

During the Antinomian Controversy in 1637, Bradstreet served as one of the magistrates who presided over the trial of Anne Hutchinson, ultimately voting for her banishment from the colony. In 1639, he was granted land in Salem, adjacent to that of John Endecott, where he resided for a period. He then moved to Ipswich in 1634 before becoming one of the founding settlers of Andover in 1648. His Andover home was later destroyed by fire in 1666, an event attributed to "the carelessness of the maid."

3. Business and Property Interests

Simon Bradstreet engaged in a variety of business ventures throughout his life, accumulating substantial wealth and property. His interests included active land speculation and investments in a ship involved in the coasting trade, which facilitated commerce along the colonial coastline.

In 1660, Bradstreet acquired shares in the Atherton Trading Company, a land development enterprise focused on the "Narragansett Country" (present-day southern Rhode Island). He became a leading figure within the company, serving on its management committee and publishing handbills to promote and advertise its lands. By the time of his death, Bradstreet owned over 1.5 K acre (1.50 K acre) of land distributed across five different communities within the colony.

His wealth was also linked to the institution of slavery. Historical records indicate that Bradstreet owned two enslaved individuals, a woman named Hannah and her daughter Billah. The labor and economic contributions of enslaved people were integral to the accumulation of wealth by many colonial figures, including Bradstreet.

4. Political Career (Pre-Governorship)

Simon Bradstreet maintained an almost continuous involvement in the political affairs of the Massachusetts Bay Colony for decades before assuming the governorship. His political stances were generally moderate, a position that often placed him in contrast to the more hardline factions within the colony. This period also saw Bradstreet undertake numerous important diplomatic missions on behalf of the colony.

When the colonial council first convened in Boston, Bradstreet was selected as the colonial secretary, a crucial post he held until 1644. During this period and beyond, he advocated against legislation and judicial decisions that sought to punish individuals for openly criticizing governing magistrates, demonstrating an early commitment to what might be understood as freedom of speech. Later in his career, he was also notably outspoken in his opposition to the Salem witch trials in 1692, which deeply affected his hometown of Salem and resulted in numerous contentious legal proceedings.

Bradstreet served for many years as a commissioner representing Massachusetts to the New England Confederation, an intercolonial organization established to coordinate matters of common interest, primarily defense, among most New England colonies. He was regularly elected as an assistant, sitting on the council that oversaw the public affairs of the colony. However, he did not attain higher office until 1678, when he was first elected as deputy governor under John Leverett. He consistently opposed military interventions against the colony's foreign neighbors, arguing against official involvement in a French Acadian dispute in the 1640s and speaking out against attacking New Netherland during the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654).

4.1. Diplomatic Missions

Bradstreet was frequently dispatched on critical diplomatic missions, negotiating with various groups including settlers, other English colonies, and the Dutch in New Amsterdam. In 1650, he was sent to Hartford, Connecticut, where he participated in the negotiations for the Treaty of Hartford. This treaty was crucial in defining the boundary between the English colonies and New Amsterdam. In the years that followed, he successfully negotiated an agreement with settlers in York and Kittery, which effectively brought these communities under Massachusetts jurisdiction.

5. Relations with the English Crown

Simon Bradstreet's interactions with the English monarchy, particularly after the English Restoration of Charles II in 1660, were complex and often strained, reflecting the ongoing struggle between colonial autonomy and imperial control.

In 1661, following Charles II's return to the throne, colonial authorities in Massachusetts became increasingly anxious about preserving their charter rights. Bradstreet was appointed to head a legislative committee tasked with considering and debating "such matters touching their patent rights, and privileges, and duty to his Majesty, as should to them seem proper." The committee drafted a letter that reaffirmed the colony's charter rights while simultaneously declaring allegiance and loyalty to the Crown. Bradstreet and John Norton were chosen as agents to deliver this letter to London.

While King Charles II renewed the charter, he sent the agents back to Massachusetts with a letter imposing significant conditions. The colony was expected to expand religious tolerance to include the Church of England and various religious minorities, such as the Quakers. Bradstreet and Norton faced harsh criticism from hardline factions within the colonial legislature upon their return. However, Bradstreet steadfastly defended the necessity of accommodating the King's wishes, viewing it as the safest course of action to protect the colony's interests.

The King's demands caused a significant division within the colony. Bradstreet was a prominent figure in the moderate "accommodationist" faction, which argued that the colony should comply with the King's desires. This faction, however, lost the debate to the hardline "commonwealth" faction, which was determined to aggressively maintain the colony's charter rights. This hardline stance was led through the 1660s by governors John Endecott and Richard Bellingham. The issue remained dormant for several years, as Charles II was preoccupied with the Second Anglo-Dutch War and domestic politics in the late 1660s. However, relations between the colony and the Crown deteriorated again in the mid-1670s when the King renewed his demands for legislative and religious reforms, which were once more resisted by the hardline magistrates.

6. Governorship (1679-1684)

Simon Bradstreet's tenure as governor was marked by ongoing tension with the English Crown and the challenge of defending the colony's interests, which also included crucial defense efforts during King William's War.

In early 1679, Governor John Leverett died, and Simon Bradstreet, as his deputy, succeeded him. Leverett had previously opposed accommodating the King's demands, and the shift to an "accommodationist" leadership under Bradstreet came too late to prevent the impending crisis. Bradstreet would ultimately serve as the last governor under the colony's original charter. His deputy, Thomas Danforth, represented the opposing "commonwealth" faction, creating a complex political dynamic during his tenure.

During Bradstreet's governorship, Crown agent Edward Randolph was actively present in the colony, attempting to enforce the Navigation Acts, which regulated colonial trade and made certain types of commerce illegal. Randolph's enforcement efforts met with vigorous resistance from both the merchant class and sympathetic magistrates, despite Bradstreet's attempts to find a middle ground. Juries frequently refused to convict ships accused of violating these acts; in one notable instance, Bradstreet attempted three times to persuade a jury to alter its verdict.

Randolph's persistent efforts to enforce the navigation laws eventually convinced the colony's general court that it needed to establish its own mechanisms for enforcement. A bill to create a naval office was intensely debated in 1681. The House of Deputies, dominated by the commonwealth party, opposed the idea, while the moderate magistrates supported it. The bill that finally passed was a victory for the commonwealth party, making enforcement difficult and susceptible to retaliatory lawsuits. Bradstreet, however, refused to fully implement the law, and Randolph publicly challenged its legitimacy. Bradstreet's re-election in 1682 somewhat vindicated his position, and he subsequently used his judicial authority to further undermine the law's effects.

Randolph's threats to report the colonial legislature's intransigence to the Crown prompted the colony to dispatch agents to England to argue their case. However, the powers granted to these agents were limited. Shortly after their arrival in late 1682, the Lords of Trade issued an ultimatum to the colony: either grant its agents broader powers, including the authority to negotiate modifications to the charter, or risk having the charter voided. The general court responded by instructing its agents to adopt a hardline stance. Following legal proceedings initiated in 1683, the Massachusetts Bay Colony's charter was formally annulled on October 23, 1684.

7. Dominion of New England and Interim Leadership

Following the annulment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony's charter, King Charles II established the Dominion of New England in 1684. Bradstreet's brother-in-law, Joseph Dudley, who had previously served as a colonial agent, was commissioned by King James II as President of the Council for New England in 1685 and assumed control of the colony in May 1686. Bradstreet was offered a position on Dudley's council but declined.

Dudley was replaced in December 1686 by Sir Edmund Andros, whose administration became deeply unpopular in Massachusetts. Andros was known for vacating existing land titles and seizing Congregational church properties for Church of England religious services, actions that generated widespread resentment. Andros's high-handed rule also proved unpopular in the other colonies that were part of the Dominion.

The idea of a revolt against Andros began to circulate as early as January 1689, even before news of the Glorious Revolution of December 1688 reached Boston. After William III and Mary II ascended to the English throne, Increase Mather and Sir William Phips, Massachusetts agents in London, petitioned them and the Lords of Trade for the restoration of the Massachusetts charter. Mather also persuaded the Lords of Trade to delay informing Andros of the revolution. He had already sent a letter to Bradstreet containing news of a pre-revolution report which stated that the charter had been illegally annulled and advised the magistrates to "prepare the minds of the people for a change."

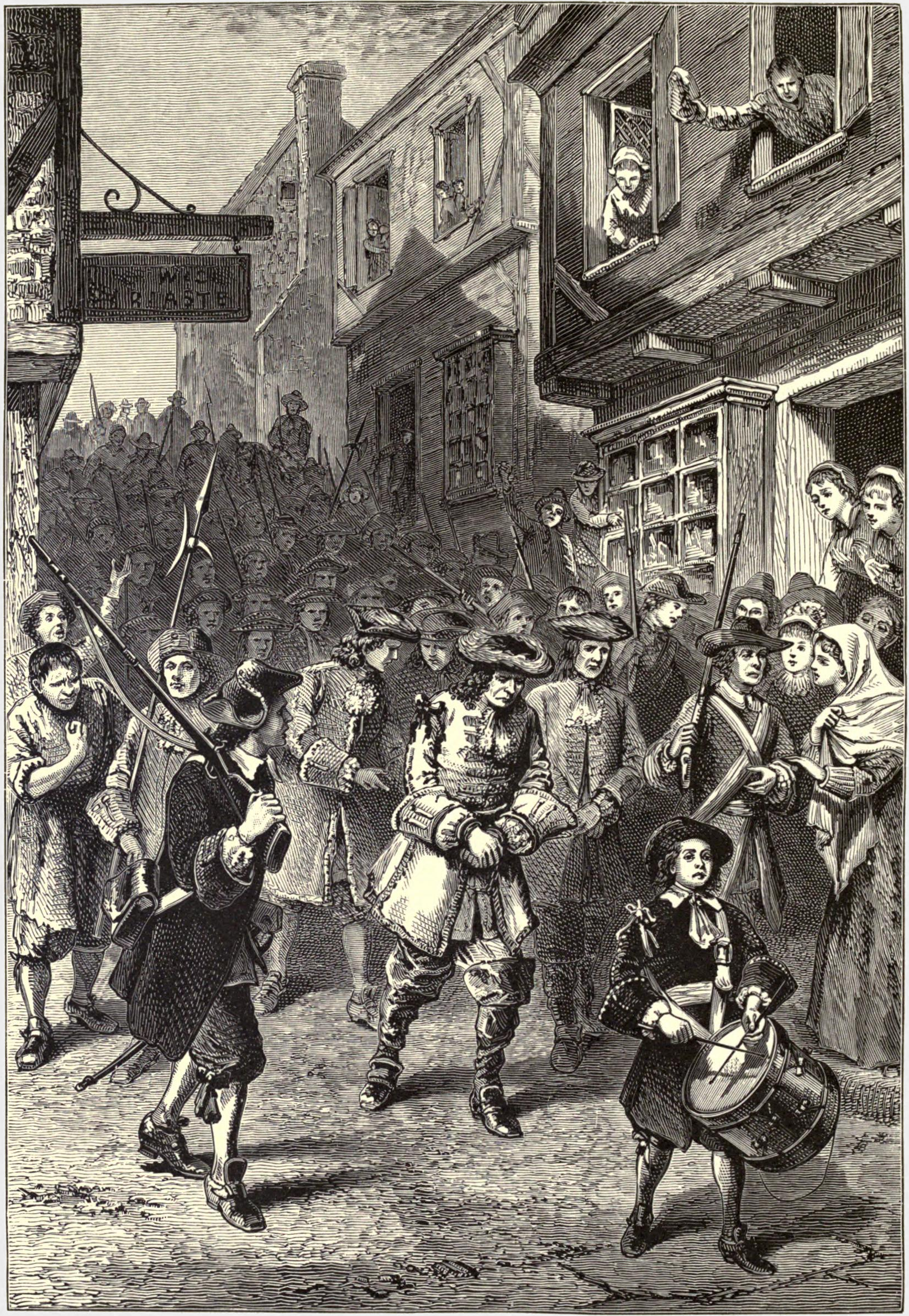

News of the revolution reached some individuals as early as late March, and Bradstreet is considered one of several possible organizers of the mob that formed in Boston on April 18, 1689. On that day, Bradstreet, along with other pre-Dominion magistrates and some members of Andros's council, addressed an open letter to Andros, demanding his surrender to quell the uprising. Andros, who had sought refuge on Castle Island, surrendered and was eventually returned to England after several months of confinement.

In the aftermath of Andros's arrest, a council of safety was formed, with Bradstreet serving as its president. The council drafted a letter to William and Mary, justifying the colony's actions using language similar to that employed by William in his own proclamations when he invaded England. The council swiftly decided to revert to the system of government that had existed under the old charter. Under this restored form, Bradstreet resumed the governorship and was annually re-elected until 1692. He faced the challenge of defending the colony against those who opposed the reintroduction of the old rule, whom he characterized in reports to London as "malcontents" and "strangers stirring up trouble."

7.1. Defense During King William's War

During his interim governorship, Bradstreet also played a crucial role in managing the colony's defense, particularly its northern frontier, which was frequently subjected to Native American raids during King William's War (1688-1697). To bolster colonial security, Bradstreet approved the expeditions led by Sir William Phips in 1690 against Acadia and Quebec, aiming to secure the colony's borders and reduce external threats.

8. Later Life and Death

In 1691, William and Mary issued a new charter establishing the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and William Phips was appointed as its first governor. Bradstreet was offered a position on Phips's council when the new governor arrived in 1692, but he declined, effectively retiring from public office.

Simon Bradstreet spent his final years in Salem, Massachusetts, where he died at his home on March 27, 1697, at the remarkable age of 93. Given his longevity, Cotton Mather posthumously honored him by referring to him as the "Nestor of New England," referencing the wise and long-lived elder of the Achaeans in Greek mythology. Bradstreet was laid to rest in the Charter Street Burying Ground in Salem.

9. Family and Personal Life

Simon Bradstreet's personal life was intertwined with prominent figures and significant events in colonial American history. In 1628, he married Anne Dudley, the daughter of Massachusetts co-founder Thomas Dudley. Anne Bradstreet became celebrated as New England's first published poet, with her poetry released in England in 1650. Her works include verses that express profound and enduring love for her husband, as seen in the excerpt from "To my Dear and Loving Husband":

- "If ever two were one, then surely we;"

- "If ever man were loved by wife, then thee;"

- "If ever wife was happy in a man,"

- "Compare with me, ye women, if you can."

- "I prize thy love more than whole mines of gold,"

- "Or all the riches that the East doth hold."

Anne Bradstreet died in 1672. Together, Simon and Anne had eight children, seven of whom survived infancy. Their children included Dudley Bradstreet and John Bradstreet. In 1676, Simon Bradstreet married for a second time, to Ann Gardner, who was the widow of Captain Joseph Gardner and the daughter of Thomas Gardner of Salem.

Bradstreet's extensive family legacy continues to be recognized through his numerous notable descendants who have made significant contributions to American history and jurisprudence. These include esteemed legal scholars such as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and David Souter, as well as prominent figures like U.S. President Herbert Hoover, U.S. Senator John Kerry, and actor Humphrey Bogart.

10. Historical Assessment and Legacy

Simon Bradstreet's historical significance lies in his longevity, his consistent political involvement, and his nuanced approach to the challenges faced by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, particularly in its relationship with the English Crown. His career provides valuable insight into the balancing act required of colonial leaders during a period of evolving imperial control.

10.1. Political Philosophy and Contributions

Bradstreet was characterized by his political moderation, a stance that distinguished him from more extreme factions within the colony. He was a notable advocate for free speech, arguing against punitive measures for those who spoke out against the governing magistrates. This commitment to open discourse is a significant aspect of his legacy. Furthermore, his outspoken opposition to the Salem witch trials of 1692 demonstrated a clear moral compass and a rejection of the prevailing hysteria, solidifying his reputation as a voice of reason during a dark period in colonial history.

His efforts to balance colonial autonomy with the demands of the English Crown were central to his political career. Bradstreet consistently sought diplomatic solutions and accommodation with the monarchy, often advising compliance with royal demands as the safest course to preserve the colony's charter rights, even when such positions were unpopular with hardline elements. His sustained efforts contributed to maintaining a degree of stability in the colony during turbulent times and represented an advocacy for certain rights within the framework of imperial rule.

10.2. Controversies and Criticisms

While largely celebrated for his moderation and contributions, Bradstreet's career was not without controversial aspects. A notable instance was his vote for Anne Hutchinson's banishment during the Antinomian Controversy in 1637. This decision, while reflective of the prevailing theological and social norms of the time, contributed to the suppression of religious dissent within the colony.

Additionally, Bradstreet's ownership of enslaved individuals, specifically a woman named Hannah and her daughter Billah, represents a significant point of criticism from a modern historical perspective. This practice, common among many prominent figures of the era, underscores the complex moral landscape of colonial society and the economic reliance on forced labor, which contributed to his accumulated wealth. A balanced historical assessment must acknowledge these aspects of his career alongside his more celebrated contributions.

10.3. Enduring Influence and Notable Descendants

Simon Bradstreet's career had a lasting impact on New England history, particularly in the shaping of its political development and its relationship with England. His efforts to navigate the complexities of colonial governance and imperial demands contributed to the foundations of self-governance that would later inform the American Revolution.

Beyond his direct political influence, Bradstreet's legacy has been carried through his extensive family line. His descendants include a remarkable number of prominent figures who have significantly contributed to American society and jurisprudence, including Supreme Court Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and David Souter, U.S. President Herbert Hoover, U.S. Senator John Kerry, and actor Humphrey Bogart, demonstrating an enduring family influence across centuries of American history.