1. Biography

Jang Ok-jeong's life was a series of dramatic turns, from her humble beginnings to becoming queen, and her eventual tragic demise, all deeply intertwined with the volatile political landscape of Joseon.

1.1. Early Life and Background

Jang Ok-jeong was born on 3 November 1659 (음력 9월 19일lunar September 19Korean) in Sangpyeong-bang, Hanseongbu (modern-day Eunpyeong District, Seoul). She was the youngest daughter of Jang Hyeong (장형Jang HyeongKorean, 1623-1669) and his second wife, Lady Yun of the Papyeong Yun clan (파평 윤씨Papyeong Yun-ssiKorean, 1626-1698). Her father, Jang Hyeong, served as a Bongsa (a junior official, rank 8) in the Sa-yeokwon, the Bureau of Interpreters, before retiring early to enjoy music.

Her family belonged to the Jungin class, a social stratum below the scholar-officials but above commoners. While not part of the traditional literati elite, her family was notably affluent and influential. Her paternal grandfather, Jang Eung-in, was a renowned interpreter during King Seonjo's reign, reaching the rank of Cheomji Jungchubu-sa (a military official, rank 3) and known for his poetic talent and adherence to the principle of "goodness." Her maternal grandfather, Yun Seong-rip, was a Japanese language interpreter who served as a Cheomjeong (rank 4). Her maternal uncle, Yun Jeong-seok, was a prominent cotton cloth merchant in Yukui-jeon, the powerful Six Licensed Stores, indicating significant wealth. This background suggests that her family, though not scholar-officials, held considerable social standing and wealth, challenging later narratives that portrayed her as coming from an impoverished or low-status background.

Jang Ok-jeong had an elder half-brother, Jang Hui-sik (1640-1718), and a full elder brother, Jang Hui-jae (장희재Jang Hui-jaeKorean, 1651-29 October 1701). Jang Hui-jae was a skilled martial artist and served in the royal guard (Naegeumwi) and later as a police chief (Podobujang) even before his sister became a royal consort, indicating the family's established position. Her grand-uncle, Jang Hyeon, was a highly successful interpreter who amassed immense wealth and held high official positions, further demonstrating the family's prominence.

1.2. Entry into the Palace

The exact timing of Jang Ok-jeong's entry into the palace is unclear, but records suggest she entered at a young age, possibly before she was old enough to braid her own hair, indicating she was selected as a court lady (gungnyeo) rather than entering due to poverty. She served in the court of Grand Queen Dowager Jaui (Queen Injo's second consort and King Sukjong's step-great-grandmother). Grand Queen Dowager Jaui showed particular affection for Jang Ok-jeong, even arranging for her care outside the palace during her temporary expulsion.

Jang Ok-jeong first caught the attention of King Sukjong after the death of his first wife, Queen Ingyeong, in October 1680. Sukjong became deeply infatuated with her beauty and elevated her to the rank of Seungeun Sanggung (Favored Sanggung), a special position for a court lady who had shared intimacy with the king but was not yet a formal consort. However, this burgeoning relationship faced immediate opposition from Sukjong's mother, Queen Dowager Hyeonryeol, who belonged to the powerful Seoin faction. Fearing that Jang Ok-jeong, with her Namin faction connections, would influence the King to favor the Namin, Queen Dowager Hyeonryeol expelled her from the palace. This expulsion was also influenced by Queen Dowager Hyeonryeol's family, particularly her cousin Kim Seok-ju, who had previously orchestrated the downfall of Jang Ok-jeong's grand-uncle, Jang Hyeon, during the Gyeongsin Hwanguk of 1680. The Queen Dowager also sought to remove Jang to make way for the selection of a new Queen, Queen Inhyeon, whose family had political ties that suited the Seoin faction.

Jang Ok-jeong remained outside the palace until 1683. Following Queen Dowager Hyeonryeol's death in December 1683, Queen Inhyeon, Sukjong's second wife, allowed Jang Ok-jeong to return to court in 1686, possibly out of compassion or at the urging of Grand Queen Dowager Jaui.

1.3. Life as Royal Consort

Upon her return, Jang Ok-jeong quickly regained King Sukjong's favor. In December 1686, she was formally ennobled as a royal consort with the rank of Sug-won (숙원Suk-wonKorean), the lowest rank for a royal concubine. This official appointment, made directly by Sukjong rather than Queen Inhyeon, signaled his strong attachment. The Seoin faction and Queen Inhyeon attempted to curb Sukjong's favoritism towards Jang Ok-jeong by introducing Kim-ssi, a grand-niece of the Seoin leader Kim Su-hang, as a new consort (Yeong-bin Kim-ssi). However, Kim-ssi failed to win the King's affection.

The conflict between Jang Ok-jeong and Queen Inhyeon escalated. Queen Inhyeon reportedly ordered Jang Ok-jeong to be beaten and made disparaging remarks about her background and her inability to bear a son. This tension reached a peak with the "Jade Palanquin Incident" in November 1688. When Jang Ok-jeong's mother, Lady Yun, was summoned to the palace to assist with her daughter's postpartum care, she rode in an okgyo (a covered palanquin typically reserved for high-ranking officials' wives or royal women). This was a customary practice for mothers of new princes entering the palace. However, Yi Ik-su, a Censorate official aligned with the Seoin faction, ordered Lady Yun to be forcibly removed from her palanquin and her servants beaten, citing a minor legal technicality about her social status. This public humiliation deeply angered King Sukjong, who viewed it as a direct challenge to his authority and a deliberate insult to his favored consort. Despite strong opposition from Seoin officials, Sukjong sought to punish those involved, though he was ultimately forced to compromise.

This incident was a catalyst for Sukjong's decisive actions. On 11 January 1689, Sukjong announced his intention to designate Yi Yun, Jang Ok-jeong's son, as Wonja (the King's first son and heir apparent). This was a highly controversial move, as Yi Yun was a concubine's son, and Queen Inhyeon was still young enough to bear a legitimate heir. The Seoin faction, led by Song Si-yeol, vehemently opposed this, arguing that it undermined the Queen's position and the principle of primogeniture. Sukjong, however, saw this opposition as a direct challenge to his royal authority. He swiftly designated Yi Yun as Crown Prince on 15 January 1689, and simultaneously elevated Jang Ok-jeong to the rank of Bin (빈BinKorean), the highest rank for a royal consort, with the prefix Hui (희HuiKorean), meaning "beautiful" or "auspicious," thus becoming Jang Hui-bin. He also posthumously elevated Jang Ok-jeong's ancestors to high official ranks, including her father, Jang Hyeong, as Chief State Councillor.

The King's actions led to the Gisa Hwanguk (기사환국Gisa HwangukKorean) in March 1689. Sukjong purged the Seoin faction from power, exiling or executing many of its leaders, including Song Si-yeol. The Namin faction, which supported Jang Hui-bin and the designation of Yi Yun as Crown Prince, seized control of the government. In May 1689, Queen Inhyeon was deposed and exiled, accused of various offenses including false accusations against Jang Hui-bin and undermining royal authority.

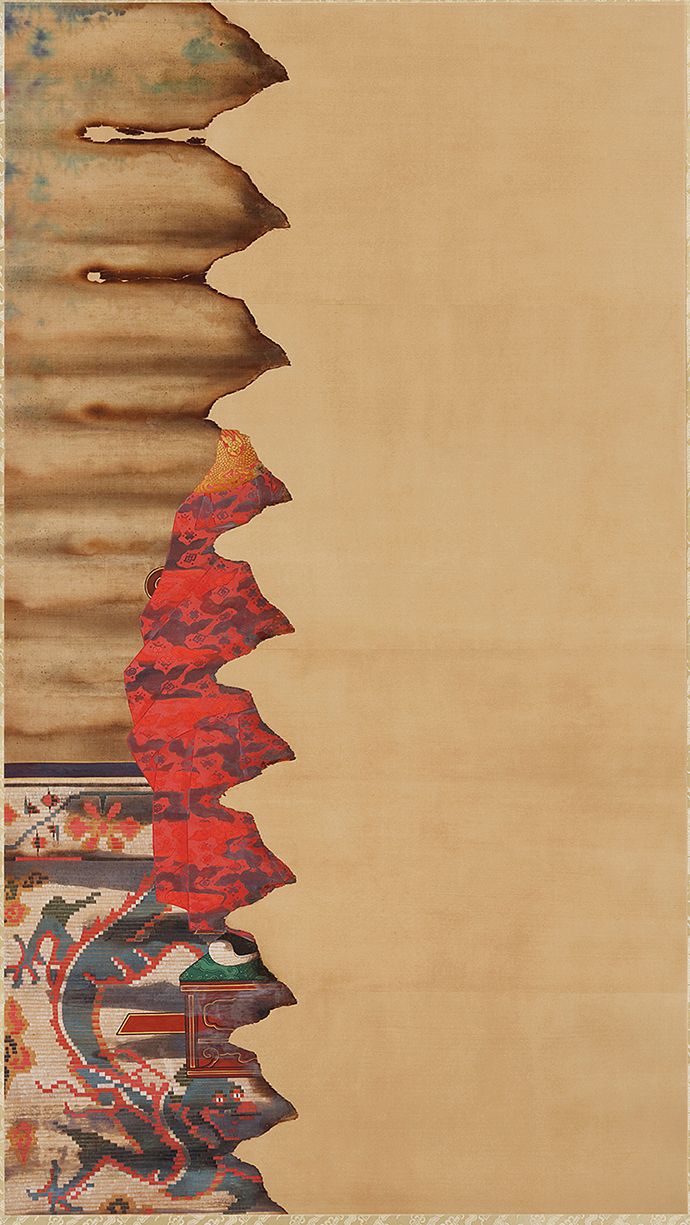

Following Queen Inhyeon's deposition, Jang Hui-bin was elevated to Queen Consort of Joseon on 22 October 1690. This was an unprecedented event in Joseon history, as it marked the first time a concubine of Jungin background had ascended to the position of Queen. Her parents were posthumously given royal titles: Jang Hyeong as Oksan Buwongun and Lady Yun as Pasan Bubuin.

1.4. Queen Consort

As Queen, Jang Ok-jeong gave birth to her second son, Yi Seong-su, on 19 July 1690. Though he was not formally titled, he was treated as a Grand Prince and received corresponding honors and land. However, Yi Seong-su died suddenly on 16 September 1690, less than two months after his birth. Records suggest Jang Ok-jeong experienced a difficult pregnancy and continued to suffer from poor health, including chronic illness and skin ailments, during her time as Queen.

Her reign as Queen was marked by the increasing influence and perceived greed of the Namin faction and her own family, particularly her brother Jang Hui-jae. This, combined with Sukjong's growing remorse over his hasty actions during the Gisa Hwanguk, began to erode his favor for her. The political climate shifted again with the rise of a new royal favorite, Choi Suk-won (later Choe Suk-bin), a former palace maid who openly supported the deposed Queen Inhyeon. Choi Suk-bin, along with members of the Noron and Soron factions, began campaigning for Queen Inhyeon's reinstatement.

By 1694, Jang Ok-jeong had largely lost the King's favor. Sukjong grew weary of the Namin faction's political dominance and the perceived arrogance of the Jang family. He also felt remorse for his past actions and the suffering of Queen Inhyeon.

1.5. Downfall and Execution

The political tide turned decisively with the Gapsul Hwanguk (갑술환국Gapsul HwangukKorean) in April 1694. This purge saw the Namin faction removed from power, with many of its leaders, including Min Am, executed or exiled. Jang Hui-jae was also banished. King Sukjong officially demoted Jang Ok-jeong from Queen Consort back to her former rank of Hui-bin, and Queen Inhyeon was reinstated as Queen. The Namin faction never politically recovered from this purge. The royal seal and documents related to Jang Ok-jeong's queenly status were ceremonially destroyed.

In 1701, Queen Inhyeon died of an unknown illness. This event triggered the final and most dramatic chapter of Jang Ok-jeong's life, known as the Mugo-ui Ok (무고의 옥Mugo-ui OkKorean, or "Witchcraft Accusation Incident"). Choi Suk-bin accused Jang Hui-bin of conspiring with a shaman priestess to curse Queen Inhyeon with black magic, gloating over her death. Queen Inhyeon's brothers, Min Jin-hu and Min Jin-won, also testified that their sister had spoken of an unusual illness, implying a curse.

It was confirmed that Jang Hui-bin had indeed set up a shrine (신당sindangKorean) at her residence, Chwiseondang Hall, and performed shamanistic rituals. However, her supporters claimed these rituals, which had been ongoing since 1699, were to pray for the recovery of Crown Prince Yi Yun, who had suffered from smallpox and subsequent eye problems. They argued that stopping the rituals would incur the wrath of spirits. Despite this defense, Sukjong publicly accused Jang Hui-bin of using black magic to murder Queen Inhyeon.

The investigation into the Mugo-ui Ok was highly controversial, marked by biased procedures, lack of concrete evidence, and confessions obtained under torture. Many, including Jang Hui-jae's concubine, were subjected to severe interrogation. Jang Hui-jae was executed in exile, and many of Jang Hui-bin's supporters, including the leader of the Soron faction, were also put to death, resulting in approximately 1,700 fatalities.

Despite pleas for mercy from the Soron faction, who emphasized her status as the Crown Prince's mother, King Sukjong remained resolute. On 7 October 1701, Sukjong issued a decree prohibiting any concubine from ever becoming Queen, a measure aimed at preventing future political instability caused by such ascensions. On 10 October 1701 (음력 10월 10일lunar October 10Korean), Jang Hui-bin was executed by poisoning at Chwiseondang Hall in Changgyeonggung Palace. She was 42 years old.

There is historical debate regarding the exact manner of her death. While popular narratives, particularly the novel Inhyeon Wanghu Jeon, depict her being forcibly poisoned, official records like the Sukjong Sillok and Seungjeongwon Ilgi (Diaries of the Royal Secretariat) state that she was ordered to commit suicide (자진jajinKorean). These official records also indicate that Sukjong initially ordered her to be given poison, but after officials argued that applying a judicial punishment to the Crown Prince's mother was forbidden by the Zhouli and that executions could not occur within the palace, Sukjong agreed to allow her to hang herself outside the palace, a method considered a form of self-execution. This suggests that the official account aimed to preserve a degree of dignity for the mother of the Crown Prince, distinguishing it from a direct, forced execution.

2. Family and Ancestry

Jang Ok-jeong's family played a significant role in her rise and fall, deeply entangled in the political currents of Joseon.

2.1. Ancestry

Jang Ok-jeong's ancestry can be traced back several generations through her paternal and maternal lines:

- Paternal Line:**

- Father:** Jang Hyeong (장형Jang HyeongKorean, 1623-1669), posthumously honored as Yeonguijeong (Chief State Councillor) and Oksan Buwongun.

- Paternal Grandfather:** Jang Eung-in (장응인Jang Eung-inKorean), posthumously honored as Uuijeong (Right State Councillor). He was a distinguished interpreter and military official during King Seonjo's reign.

- Paternal Great-Grandfather:** Jang Su (장수Jang SuKorean), posthumously honored as Jwauijeong (Left State Councillor).

- Paternal Great-Great-Grandfather:** Jang Se-pil (장세필Jang Se-pilKorean).

- Maternal Line:**

- Mother:** Lady Yun of the Papyeong Yun clan (파평 윤씨Papyeong Yun-ssiKorean, 1626-1698), second wife of Jang Hyeong, posthumously honored as Pasan Bubuin.

- Maternal Grandfather:** Yun Seong-rip (윤성립Yun Seong-ripKorean), posthumously honored as a Jeonggyeong (rank 2 official). He was a Japanese interpreter.

- Maternal Grandmother:** Lady Byeon of the Chogye Byeon clan (초계 변씨Chogye Byeon-ssiKorean). She was a grand-aunt of Byeon Seung-eop, a famous wealthy interpreter, further indicating the family's financial prominence.

2.2. Family

- Father:** Jang Hyeong (장형Jang HyeongKorean; 25 February 1623 - 12 January 1669)

- Stepmother:** Lady Go of the Jeju Go clan (제주 고씨Jeju Go-ssiKorean; ? - 1645)

- Mother (Biological):** Lady Yun of the Papyeong Yun clan (파평 윤씨Papyeong Yun-ssiKorean; 1626-1698)

- Siblings:**

- Elder half-brother:** Jang Hui-sik (장희식Jang Hui-sikKorean; 1640 - ?)

- Elder sister:** Lady Jang (장씨Jang-ssiKorean), married to Kim Ji-jung, an official in the Office of Divination.

- Elder brother:** Jang Hui-jae (장희재Jang Hui-jaeKorean; 1651 - 29 October 1701)

- Husband:** Yi Sun, King Sukjong of Joseon (이순 조선 숙종Yi Sun Joseon SukjongKorean; 7 October 1661 - 12 July 1720)

- Issue:**

- Son:** Yi Yun, King Gyeongjong of Joseon (이윤 조선 경종Yi Yun Joseon GyeongjongKorean; 20 November 1688 - 30 September 1724)

- Son:** Yi Seong-su (이성수Yi Seong-suKorean; 19 July 1690 - 16 September 1690)

3. Assessment and Legacy

Jang Ok-jeong's life and death have been subjects of intense debate and reinterpretation throughout history, reflecting shifting political and social perspectives.

3.1. Historical Interpretations

Traditionally, Jang Ok-jeong has been largely portrayed as a villainous figure, an ambitious and manipulative "femme fatale" who used her beauty to gain power and ruthlessly eliminate rivals. She is often included in the infamous list of "Joseon's Three Great Evil Women," alongside Jang Nok-su and Jeong Nan-jeong. This negative image was heavily propagated by the Noron faction, who dominated the political scene after her death and were responsible for compiling many of the historical records, including the Sukjong Sillok and popular narratives like Inhyeon Wanghu Jeon. These accounts emphasized her alleged greed, jealousy, and involvement in black magic, presenting her as the sole instigator of the political purges and the cause of Queen Inhyeon's downfall and death.

However, modern historical scholarship offers a more nuanced and critical re-evaluation of Jang Ok-jeong. Many contemporary historians argue that she was a victim of the brutal factional strife between the Namin and Seoin/Noron/Soron factions. Her rise to power, unprecedented for someone of her background, inherently challenged the rigid social hierarchy and the established political order, making her a convenient scapegoat for the faction that lost power. Her actions are often seen through the lens of a woman navigating and surviving in a highly patriarchal and politically charged environment, where her personal ambitions became intertwined with the larger power struggles of the court. The bias in historical records, particularly those compiled by her political enemies, is increasingly acknowledged, leading to a more balanced understanding of her role and character.

3.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Specific criticisms and controversies surrounding Jang Ok-jeong's life include:

- Greed and Jealousy:** Traditional narratives accuse her of insatiable greed for power and extreme jealousy towards Queen Inhyeon and other consorts, particularly Choi Suk-bin.

- Political Manipulation:** She is often blamed for instigating political purges and manipulating King Sukjong to favor the Namin faction and remove the Seoin.

- Alleged Cruelty:** Accounts, especially in popular culture, depict her as cruel and ruthless, even towards her own son. One controversial claim, found in some unofficial histories, suggests she severely beat Crown Prince Yi Yun (King Gyeongjong), causing him to be feeble-minded and unable to have offspring. However, there is no concrete evidence in official records to support this, and it is largely considered a fabrication by her detractors.

- Witchcraft Charges:** The most significant controversy is the Mugo-ui Ok, where she was accused of using black magic to curse Queen Inhyeon. While she did perform shamanistic rituals, her supporters argued these were for the Crown Prince's health, not to harm the Queen. The fairness of the investigation and the veracity of the accusations remain highly debated, with many pointing to the political motivations behind the charges.

3.3. Political Impact

Jang Ok-jeong's life had a profound and lasting impact on the political landscape of Joseon. Her rapid ascent and subsequent fall were central to the series of violent political purges known as Hwanguk.

- Gisa Hwanguk (1689):** Her elevation to Queen and the designation of her son as Crown Prince led to the complete expulsion of the Seoin faction and the Namin's rise to power. This marked a significant shift in the balance of power, with devastating consequences for the losing faction.

- Gapsul Hwanguk (1694):** Her demotion and Queen Inhyeon's reinstatement resulted in the Namin's irreversible decline and the return of the Seoin (Noron/Soron) to dominance.

- Mugo-ui Ok (1701):** The witchcraft incident and her execution further solidified the Noron's power and led to the final purge of the Soron faction, creating a highly unstable political environment that continued into the reign of her son, King Gyeongjong, and later, King Yeongjo.

Her story highlighted the dangers of factionalism and the personal toll it took on individuals within the royal court. King Sukjong's decree prohibiting concubines from ever becoming Queen, issued after her death, was a direct attempt to prevent such political turmoil from recurring.

3.4. Cultural Impact

Jang Ok-jeong's dramatic life has ensured her enduring presence in Korean popular culture. She has been a frequent subject of films, television dramas, and novels, which have significantly shaped public perception of her.

- Films:**

- Jang Hui-bin (1961), portrayed by Kim Ji-mee.

- Femme Fatale, Jang Hee-bin (1968), portrayed by Nam Jeong-im.

- Shadows in the Palace (2007), portrayed by Yoon Se-ah.

- Television Dramas:**

- Jang Hui-bin (MBC, 1971), portrayed by Youn Yuh-jung.

- Women of History: Jang Hui-bin (MBC, 1981), portrayed by Lee Mi-sook.

- 500 Years of Joseon Dynasty: Queen Inhyeon (MBC, 1988), portrayed by Jun In-hwa.

- Jang Hee Bin (SBS, 1995), portrayed by Jung Sun-kyung.

- Royal Story: Jang Hui-bin (KBS2, 2002-2003), portrayed by Kim Hye-soo.

- Dong Yi (MBC, 2010), portrayed by Lee So-yeon.

- Queen Inhyun's Man (tvN, 2012), portrayed by Choi Woo-ri.

- Jang Ok-jung, Living by Love (SBS, 2013), portrayed by Kim Tae-hee and Kang Min-ah.

- The Royal Gambler (SBS, 2016), portrayed by Oh Yeon-ah.

These portrayals often oscillate between the traditional "evil woman" image and more sympathetic interpretations that depict her as a victim of circumstances or a woman striving for love and power in a restrictive society.

4. Tomb and Commemoration

Despite her controversial life and tragic end, Jang Ok-jeong received significant posthumous honors, particularly due to her status as the biological mother of King Gyeongjong.

4.1. Daebinmyo

Jang Ok-jeong's tomb is known as Daebinmyo (대빈묘DaebinmyoKorean, "Tomb of the Great Concubine"). It was originally located in Munhyeong-ri, Opo-myeon, Gwangju-gun, Gyeonggi Province. However, in June 1969, it was relocated to the Seooreung Royal Tombs Cluster in Deogyang District, Goyang, Gyeonggi Province. This relocation was necessary due to urban expansion plans that required the original site. Daebinmyo is now situated near Myeongneung, which houses the tombs of King Sukjong, Queen Inhyeon, and Queen Inwon.

The relocation of her tomb, particularly its placement in a less prominent area within the cluster, has sometimes been misinterpreted as a sign of her continued disgrace. However, the funeral rites and burial procedures for Jang Ok-jeong were exceptionally elaborate and unprecedented for a royal concubine, even surpassing the standard for other consorts, and were managed by the royal court. Her tomb was decorated with the honors typically reserved for a first-rank royal family member, including a large designated area.

A unique feature of Daebinmyo is a large rock behind the tomb through which a pine tree has grown. This has led to speculation that it symbolizes Jang Hui-bin's enduring and powerful ki (energy). Some popular beliefs suggest that young, single women who visit the tomb and pay tribute will soon find love, reflecting a modern reinterpretation of her strong character.

4.2. Chilgung

Jang Ok-jeong's memorial tablet is enshrined in Chilgung (칠궁ChilgungKorean, "Palace of Seven Royal Concubines"), a shrine complex located in Gungjeong-dong, Seoul. Chilgung is dedicated to the biological mothers of Joseon kings who never became queens themselves. The presence of her memorial tablet here, within a structure that incorporates architectural elements typically reserved for queens (such as circular pillars), signifies her posthumous veneration and acknowledges her brief period as Queen Consort and her ultimate status as the mother of a king. In 1722, King Gyeongjong posthumously honored his mother with the title Oksan Budaebin (옥산부대빈Oksan BudaebinKorean, "Great Concubine of Oksan Prefecture"), elevating her status to match that of Deokheung Daewongun, the biological father of King Seonjo, who was also not a king.

5. Related Figures and Events

Jang Ok-jeong's life was intricately linked with several key figures and historical events of the late Joseon Dynasty:

- King Sukjong** (1661-1720): The 19th King of Joseon, her husband, whose fluctuating affections and decisive political actions shaped her destiny.

- Queen Inhyeon** (1667-1701): Sukjong's second wife, whom Jang Ok-jeong replaced as Queen and who was later reinstated. Their rivalry is a central theme in Jang Ok-jeong's story.

- Choi Suk-bin** (1670-1718): A royal concubine of King Sukjong and the biological mother of King Yeongjo. She became Sukjong's new favorite after Jang Ok-jeong's fall from grace and was instrumental in the accusations against Jang Ok-jeong during the Mugo-ui Ok.

- King Gyeongjong** (1688-1724): The 20th King of Joseon, Jang Ok-jeong's son. His fragile health and childlessness contributed to ongoing political instability.

- Song Si-yeol** (1607-1689): A prominent scholar and leader of the Noron faction, who fiercely opposed Jang Ok-jeong's rise and the designation of her son as Crown Prince, ultimately leading to his execution during the Gisa Hwanguk.

- Jang Hui-jae** (1651-1701): Jang Ok-jeong's elder brother, who gained significant power and influence during his sister's time as Queen but was later exiled and executed.

- Gisa Hwanguk** (1689): A major political purge in which the Seoin faction was removed from power, Queen Inhyeon was deposed, and the Namin faction, along with Jang Ok-jeong, rose to prominence.

- Gapsul Hwanguk** (1694): Another political purge that saw the Namin faction fall, Jang Ok-jeong demoted, and Queen Inhyeon reinstated, marking a return of the Seoin to power.

- Mugo-ui Ok** (1701): The "Witchcraft Accusation Incident," which led to Jang Ok-jeong's execution on charges of cursing Queen Inhyeon.

- Sinim Sahwa** (1721-1722): A political purge that occurred after King Gyeongjong's ascension, where the Soron faction, supporting Gyeongjong and his mother's legacy, purged the Noron faction, who had opposed Jang Ok-jeong.