1. Overview

Robert Blake, born Michael James Gubitosi, was an American actor whose extensive career spanned from child stardom to acclaimed adult roles, before becoming overshadowed by his involvement in a high-profile murder trial. Starting as a child performer in the *Our Gang* series and *Red Ryder* films, Blake successfully transitioned to mature acting, achieving critical recognition for his role as Perry Smith in the 1967 film *In Cold Blood* and winning an Emmy and Golden Globe for his portrayal of Tony Baretta in the popular 1970s television series *Baretta*. His personal life, marked by a challenging childhood and struggles with addiction, culminated in the 2001 murder of his second wife, Bonny Lee Bakley. Blake was acquitted in the subsequent criminal trial in 2005 but found civilly liable for her wrongful death, leading to significant public scrutiny and legal battles that deeply impacted his later life and public image. His career trajectory highlights both the enduring appeal of a versatile actor and the profound societal and personal consequences when celebrity intersects with crime and intense media attention.

2. Early life and background

Robert Blake's formative years were characterized by a difficult family environment and an early immersion into the demanding world of entertainment, which shaped his early career and later personal struggles.

2.1. Childhood and family background

Robert Blake was born Michael James Gubitosi on September 18, 1933, in Nutley, New Jersey. His parents were Giacomo (James) Gubitosi (1906-1956) and Elizabeth Cafone (1910-1991). His father, James, initially worked as a die setter for a can manufacturer. Both parents eventually embarked on a song-and-dance act. In 1936, the three Gubitosi children, including Michael, began performing together, billed as "The Three Little Hillbillies." The family relocated to Los Angeles, California, in 1938, where the children started working as movie extras.

Blake's childhood was marked by unhappiness and abuse. He later described being physically and sexually abused by both of his alcoholic parents, often being locked in a closet and forced to eat off the floor as punishment. When he began attending public school at the age of 10, he faced bullying and engaged in fights with other students, ultimately leading to his expulsion. At 14, he ran away from home, enduring several more challenging years. His father died by suicide in 1956, and Blake notably refused to attend his funeral.

2.2. Military service and early difficulties

In 1950, Blake was drafted into the U.S. Army during the Korean War. Upon his discharge at the age of 21, he faced significant difficulties in finding employment, leading to a deep depression. This period also saw him develop a two-year addiction to heroin and cocaine, during which he also engaged in drug dealing. These struggles marked a challenging transition from his childhood acting career to his adult life.

3. Career

Robert Blake's career spanned several decades, evolving from a child actor to a celebrated dramatic performer in both film and television, with his later years marked by a dramatic shift in his public persona due to legal entanglements.

3.1. Child actor

Blake began his acting career in 1939, initially credited as Mickey Gubitosi, in the MGM film Bridal Suite. He then joined MGM's Our Gang (also known as The Little Rascals) short subjects series, replacing Eugene "Porky" Lee. He appeared in 40 shorts between 1939 and 1944, eventually becoming the series' final lead character. His parents also made appearances as extras in the series. While in Our Gang, Blake's character, Mickey, was often required to cry, a performance for which he was sometimes criticized for being unconvincing, and his character was perceived by some as obnoxious and whiny.

In 1942, he adopted the stage name Bobby Blake and secured his first starring role in a feature film, playing the title character in the MGM feature Mokey, which also starred Donna Reed and Our Gang co-star Billie "Buckwheat" Thomas. Following this name change, his character in Our Gang was renamed "Mickey Blake." He also appeared as "Tooky" Stedman in the 1942 film Andy Hardy's Double Life. After MGM discontinued Our Gang in 1944, Blake was later honored by the Young Artist Foundation in 1995 with a Former Child Star "Lifetime Achievement" Award for his contributions to the series.

In 1944, Blake began a notable role as "Little Beaver," a Native American boy, in the Red Ryder Western series produced by Republic Pictures. He appeared in 23 of these films until 1947. Blake, who was of Italian-American heritage, was frequently cast as Native American or Latino characters throughout his career, a common practice in Hollywood during that era. His early filmography also includes roles in The Big Noise (1944) with Laurel and Hardy, Humoresque (1946) where he played a young version of John Garfield's character, and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), in which he played a Mexican boy. By 1950, at age 17, Blake appeared as Mahmoud in The Black Rose and as an uncredited Enrico, a Naples Bus Boy, in Black Hand.

3.2. Transition to adult roles

Upon leaving the U.S. Army at age 21, Blake diligently worked on improving his personal and professional life. He enrolled in Jeff Corey's acting class, a pivotal step that helped him become a seasoned Hollywood actor. In 1956, he was first billed under the name Robert Blake, marking his official transition to adult roles. This period saw him take on increasingly notable dramatic performances in both films and television. Author Michael Newton has lauded Blake's career as "one of the longest in Hollywood history," a testament to his successful and enduring shift from child stardom to a respected adult acting career.

3.3. Acting training and career development

Blake's commitment to his craft was evident in his participation in Jeff Corey's renowned acting class, where he honed his skills and rebuilt his professional life after his military service and struggles with addiction. A significant turning point in his career development came through his relationship with entertainment attorney Louis L. Goldman, who was introduced to Blake by actor John F. Kennedy war biopic PT 109 as Charles "Bucky" Harris (1963). Goldman played a crucial role in guiding Blake, helping him navigate the complexities of Hollywood and avoid legal troubles. Blake himself described Goldman as a mentor who provided him with the necessary emotional and psychological support to succeed, stating that Goldman "kept me out of the courtrooms" and handled various on-set issues and industry negotiations.

: "Lou was Cus D'Amato. He took me under his wing. He said, 'Robert, you have to listen to me. Otherwise you're never going to make it.' And somehow he had the emotional and the psychological wherewithal to get me to respect and love him. And he kept me out of the courtrooms. Many's the time he went back in the judge's chambers and drug me back there and solved the problem that was going to turn into a nightmare. [He'd] [c]ome on the set and handle things; once [he went] to Lew Wasserman's office and said, 'Don't worry, I'll handle it, I'll fix it'... For some reason or other, I listened to him. When I was with him I was like a little boy. And I would apologize. I'd say 'God, Lou, I'm sorry.' He had a way of getting to your heart so that the junkyard dog was not there with him. And he took care of all of us in that way. I was very lucky."

This mentorship was instrumental in setting Blake on a more stable and successful career path.

3.4. Major film appearances

Blake's career as an adult actor saw him take on a variety of significant roles, cementing his reputation as a versatile and intense performer. In 1959, he appeared in Pork Chop Hill and starred in The Purple Gang (1960), a gangster film. He also took on a featured role as one of four U.S. soldiers involved in a gang rape in occupied Germany in Town Without Pity (1961). In 1963, he appeared as Charles "Bucky" Harris in the John F. Kennedy war biopic PT 109. Other notable films during this period include Ensign Pulver (1964) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).

His career reached a new height in 1967 with his breakout performance in In Cold Blood, where he played real-life murderer Perry Smith, a role for which he was physically well-suited. The film earned its director Richard Brooks two Oscar nominations. Notably, Blake was the first actor to utter the expletive "bullshit" in a mainstream American motion picture in this film.

Blake continued to take on diverse film roles, portraying a Native American fugitive in Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969) and a motorcycle highway patrolman in the iconoclastic Electra Glide in Blue (1973). In 1972, he starred as a small-town stock car driver in Corky, a film that featured real NASCAR drivers like Richard Petty and Cale Yarborough. His later film roles included Coast to Coast (1980), Second-Hand Hearts (1981), Money Train (1995), and his final film appearance as the enigmatic Mystery Man in David Lynch's Lost Highway (1997).

3.5. Major television appearances and awards

Robert Blake's television career was extensive and highly successful, particularly in the 1970s. In 1959, he appeared as Tobe Hackett in the syndicated Western series 26 Men and twice as "Alfredo" in The Cisco Kid. He also had three distinctive guest lead roles in the CBS series Have Gun Will Travel and one-time guest roles in The Restless Gun, The Rebel, Bat Masterson, The Californians, Straightaway, and Laramie. Blake was also part of the ensemble cast of the acclaimed but short-lived 1963 series The Richard Boone Show, appearing in 15 of its 25 episodes.

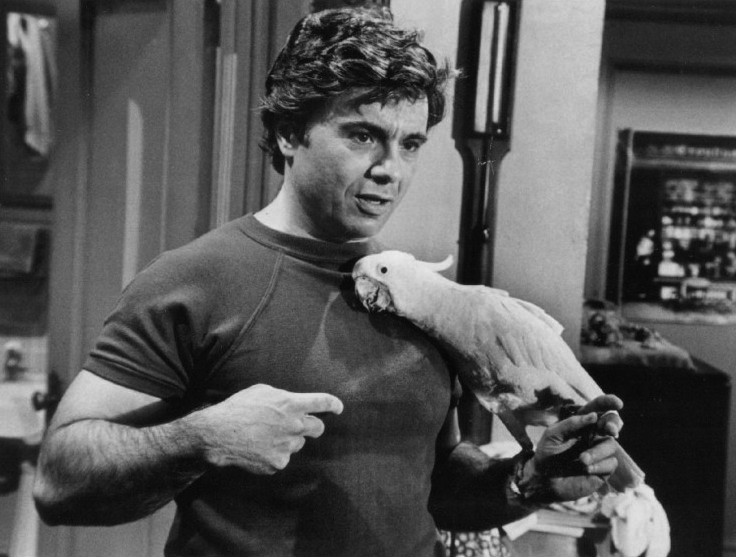

Blake is perhaps most widely recognized for his portrayal of street-wise, plainclothes police detective Tony Baretta in the popular television series Baretta (1975-1978). The show became a major hit, known for Baretta's pet cockatoo "Fred" and his signature phrases such as "That's the name of that tune" and "You can take that to the bank." His performance in Baretta earned him widespread critical acclaim, including the 27th Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series and a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor - Television Series Drama in 1975.

After Baretta concluded, NBC offered Blake a deal to produce pilot episodes for a proposed series titled Joe Dancer, where he would star as a hard-boiled private detective. Blake was also credited as the executive producer and creator of the concept. Three television films for Joe Dancer aired in 1981 and 1983, but a full series did not materialize.

Blake continued to act throughout the 1980s and 1990s, primarily in television. His notable roles included Jimmy Hoffa in the miniseries Blood Feud (1983) and John List in the murder drama Judgment Day: The John List Story (1993), which earned him a third Emmy nomination. In 1985, he starred in the television series Hell Town, playing a priest working in a tough neighborhood, and also wrote the screenplay for the pilot under the name Lyman P. Docker.

4. Personal life

Robert Blake's personal life was marked by several significant relationships and a marriage that would ultimately lead to a high-profile murder trial.

4.1. Marriages and children

Robert Blake's first marriage was to actress Sondra Kerr in 1961. The couple had two children: a son, Noah Blake, born in 1965, who also became an actor, and a daughter, Delinah Blake, born in 1966. Their marriage lasted for over two decades, ending in divorce in 1983.

Years later, in March 2016, Blake, at the age of 82, revealed he was in a new relationship with an unnamed woman. In 2017, he applied for a marriage license with his fiancée, Pamela Hudak, an event planner he had known for many years and who had testified on his behalf during his trial. However, on December 7, 2018, it was announced that Blake had filed for divorce from Hudak.

4.2. Relationship with Bonny Lee Bakley

In 1999, Blake met Bonny Lee Bakley, originally from Wharton, New Jersey. Bakley had a history of nine previous marriages and was known for reportedly seeking to exploit older men, particularly celebrities, for financial gain. During her relationship with Blake, she was also dating Christian Brando, the son of acclaimed actor Marlon Brando. Bakley became pregnant and initially claimed to both Brando and Blake that the child was theirs, even naming the baby "Christian Shannon Brando."

Blake insisted on a DNA test to confirm paternity. Following the DNA results, which proved Blake was the biological father, he married Bakley on November 19, 2000, making her his tenth wife. After paternity was established, their daughter's name was legally changed to Rose Lenore Sophia Blake. Following Bakley's murder, custody of Rose was given to Blake's daughter, Delinah. Blake remained married to Bakley until her death on May 4, 2001.

5. Murder of Bonny Lee Bakley and legal proceedings

The murder of Bonny Lee Bakley and the subsequent legal proceedings involving Robert Blake became a sensational case, drawing significant media attention and highlighting complex issues of celebrity, justice, and public perception.

5.1. Circumstances of the murder

On the evening of May 4, 2001, Robert Blake and Bonny Lee Bakley had dinner at Vitello's Italian Restaurant in Studio City, California. After the meal, Bakley was fatally shot in the head while sitting in Blake's vehicle, which was parked on a side street around the corner from the restaurant. Blake claimed he had returned to the restaurant to retrieve a pistol he had left inside and stated he was not present when the shooting occurred. The pistol Blake left in the restaurant was later found by police and confirmed not to be the murder weapon.

5.2. Arrest and criminal trial

On April 18, 2002, Robert Blake was arrested and charged with Bonny Lee Bakley's murder. His longtime bodyguard, Earle Caldwell, was also arrested and charged with conspiracy in connection with the murder. A crucial development leading to Blake's arrest was the agreement of a retired stuntman, Ronald "Duffy" Hambleton, to testify against him. Hambleton alleged that Blake had attempted to hire him to murder Bakley. Another retired stuntman and Hambleton's associate, Gary McLarty, came forward with a similar account. According to author Miles Corwin, Hambleton only agreed to testify after facing the threat of a grand jury subpoena and a misdemeanor charge.

On April 22, 2002, Blake was formally charged with one count of murder with special circumstances, an offense that carried a possible death penalty. He also faced two counts of solicitation of murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder. Blake pleaded not guilty to all charges. After nearly a year in jail, Blake was granted bail on March 13, 2003, set at 1.50 M USD. He was then placed under house arrest pending his trial. On October 31, 2003, in a significant setback for the prosecution, the judge dismissed the conspiracy charges against both Blake and Caldwell during a pre-trial hearing. In a November 2003 interview for the CBS program 48 Hours Investigates, junior prosecutor Shellie Samuels admitted that the prosecution lacked forensic evidence directly implicating Blake in the murder and could not link him to the murder weapon.

5.3. Acquittal in criminal trial

Robert Blake's criminal trial for the murder of Bonny Lee Bakley commenced on December 20, 2004, with opening statements from both the prosecution and the defense. The prosecution argued that Blake intentionally murdered Bakley to escape a loveless marriage, while the defense contended that Blake was an innocent victim of circumstantial and fabricated evidence. Both McLarty and Hambleton testified that Blake had asked them to kill Bakley. However, during cross-examination, the defense highlighted McLarty's mental health issues and Hambleton's criminal history. A key element of the defense's case was the absence of gunshot residue on Blake's hands, suggesting he was not the shooter. Blake chose not to testify during the trial.

On March 16, 2005, Blake was found not guilty of murder and not guilty of one of the two counts of solicitation of murder. The remaining count of solicitation was dropped after the jury revealed they were deadlocked 11-1 in favor of an acquittal. Los Angeles County District Attorney Stephen Cooley publicly expressed strong disapproval of the verdict, calling Blake "a miserable human being" and criticizing the jurors as "incredibly stupid" for accepting the defense's arguments. Public opinion regarding the verdict was divided, with some convinced of Blake's guilt, while others believed there was insufficient evidence for a conviction. Following his acquittal, some of Blake's fans reportedly celebrated at Vitello's, the restaurant where he and Bakley had dined before her death.

5.4. Civil lawsuit and liability

Despite his acquittal in the criminal trial, Bonny Lee Bakley's three children filed a civil suit against Robert Blake, asserting that he was responsible for their mother's death. During the civil trial, the girlfriend of Blake's co-defendant Earle Caldwell testified that she believed both Blake and Caldwell were involved in the crime.

On November 18, 2005, a civil jury found Blake liable for the wrongful death of his wife and ordered him to pay 30.00 M USD in damages. In response, Blake filed for bankruptcy on February 3, 2006. His attorney, M. Gerald Schwartzbach, appealed the civil court's decision on February 28, 2007. On April 26, 2008, an appeals court upheld the civil verdict but reduced Blake's penalty assessment to 15.00 M USD.

Blake's legal troubles continued after the civil case, including debts of 3.00 M USD for unpaid legal fees, as well as state and federal taxes. On April 9, 2010, the state of California filed a tax lien against Blake for 1.11 M USD in unpaid back taxes.

5.5. Christian Brando allegations

During the legal proceedings, Robert Blake accused Christian Brando, the son of Marlon Brando, of being involved in Bonny Lee Bakley's murder, alleging that Brando and Bakley had an affair. Brando, however, denied any involvement in the incident and invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, refusing to testify. The lack of his testimony and the inconclusive nature of the investigation left the truth of his alleged involvement unconfirmed. Blake's defense team in the civil trial also raised theories about a "third party" being involved, implying that other individuals might have been responsible for Bakley's death. This aspect of the case further complicated the narrative and contributed to the public's divided opinions on Blake's guilt. The comparison to the O. J. Simpson murder case often arose, as both cases involved celebrity defendants acquitted in criminal court but found liable in civil proceedings for the death of their former spouses.

6. Later life and activities

Following the conclusion of his legal battles, Robert Blake maintained a somewhat low profile but gradually re-engaged with the public through interviews and online platforms, offering personal reflections on his life and the controversies he faced.

6.1. Post-trial public activities

After his acquittal and bankruptcy filing, Robert Blake largely stayed out of the public eye. However, he gradually began to re-engage with the media. On July 16, 2012, Blake was interviewed on CNN's Piers Morgan Tonight. During the interview, when questioned about the night of Bakley's murder, Blake became defensive and angry, expressing resentment at what he perceived as an interrogation. Morgan clarified that he was merely asking questions that the public sought answers to.

In January 2019, Blake was featured in an interview by 20/20. Although he initially appeared reluctant, delegating to a friend, he eventually participated, discussing the murder, the conduct of the police officers involved, the culture of Hollywood and its reaction to the event, and his challenging early life with his parents.

In September 2019, Blake launched a YouTube channel titled "Robert Blake: I ain't dead yet, so stay tuned," where he shared discussions about his life and career. In 2021, he further expanded his public presence by launching a website, "Robert Blake's Pushcart," offering access to scripts, memorabilia, and his autobiography, Tales of a Rascal, for reading and purchase.

6.2. Family relationships and personal reflections

In October 2019, Blake's daughter, Rose Lenore, spoke publicly about her childhood and the profound impact of the trial on her life. She shared details about reuniting with her father and visiting her mother's grave. Rose also expressed her own aspirations to pursue acting. Regarding the truth about her mother's murder and whether her father was involved, she stated that she preferred not to know the details but remained open to discovering the truth "if it's ever an option."

Quentin Tarantino's 2021 novel, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which is based on his film of the same name, was notably dedicated to Robert Blake. The novel's character Cliff Booth, portrayed by Brad Pitt in the film, is accused of murdering his wife, a storyline that mirrors aspects of Blake's later life and legal struggles, drawing parallels between the fictional narrative and Blake's real-life controversies.

7. Death

Robert Blake's death in 2023 marked the end of a life characterized by both artistic achievement and profound personal tragedy, leading to further public discussion about his controversial legacy.

7.1. Circumstances of death

Robert Blake died from heart disease in Los Angeles, California, on March 9, 2023, at the age of 89.

7.2. Mourning and reactions

Following Robert Blake's death, there was public discussion regarding his inclusion in annual tributes within the entertainment industry. During the 95th Academy Awards on March 12, 2023, comedian Jimmy Kimmel jokingly addressed whether Blake should be part of the "In Memoriam" montage, inviting viewers to "vote." Blake was ultimately not included in the televised "In Memoriam" segment of the Academy Awards. His son, Noah Blake, publicly criticized this omission, lamenting the lack of recognition for his father's extensive career. Blake was also notably absent from the "In Memoriam" montage at the 75th Primetime Emmy Awards. However, he was featured in the 2023 'TCM Remembers' montage, an annual tribute presented by Turner Classic Movies to honor those who have passed from the film industry.

8. Assessment and impact

Robert Blake's career, marked by versatility and intensity, is evaluated alongside the significant controversies of his personal life, particularly the murder trial, which profoundly impacted his public perception and fueled discussions about celebrity justice.

8.1. Critical assessment of career

Robert Blake possessed a unique and enduring talent that allowed him to successfully navigate the challenging transition from child actor to adult performer, a feat few achieve in Hollywood. His career trajectory, spanning nearly six decades, is a testament to his versatility and commitment to the craft. He was adept at portraying complex and often troubled characters, from the chillingly nuanced Perry Smith in In Cold Blood to the street-smart detective Tony Baretta. Critics often praised his raw intensity and ability to inhabit diverse roles, including minority characters, despite his Italian-American background. His performances, particularly in films like In Cold Blood and television series like Baretta, demonstrated a remarkable range, securing his legacy as a formidable dramatic actor in film and television history.

8.2. Controversies and public perception

The murder trial and subsequent civil lawsuit following the death of Bonny Lee Bakley irrevocably altered Robert Blake's public perception. Despite his acquittal in criminal court, the civil finding of liability for wrongful death created a lasting stigma. The case fueled widespread media scrutiny, transforming Blake from a celebrated actor into a controversial figure and prompting public debates on themes such as celebrity justice, the reliability of circumstantial evidence, and the influence of public opinion on legal outcomes. His situation was often compared to that of O. J. Simpson, who also faced criminal acquittal followed by civil liability for a spousal death, further emphasizing the perceived disconnect between legal and moral accountability in celebrity cases. The extensive media coverage and the unresolved questions surrounding Bakley's murder indelibly linked Blake's name to scandal, overshadowing his earlier artistic achievements in the public consciousness and illustrating the profound impact personal scandal can have on a public life.

9. Filmography

A comprehensive list of Robert Blake's acting credits in film and television.

9.1. Film

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | Bridal Suite | Toto | Uncredited |

| 1939 | Joy Scouts | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1939 | Auto Antics | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1939 | Captain Spanky's Showboat | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1939 | Dad for a Day | Mickey | Short film |

| 1939 | Time Out for Lessons | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | Alfalfa's Double | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | The Big Premiere | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | All About Hash | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | The New Pupil | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | Spots Before Your Eyes | Kid | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | Bubbling Troubles | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | I Love You Again | Edward Littlejohn Jr. | Uncredited |

| 1940 | Good Bad Boys | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | Waldo's Last Stand | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | Goin' Fishin' | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1940 | Kiddie Kure | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Fightin' Fools | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Baby Blues | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Ye Olde Minstrels | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | 1-2-3 Go | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Robot Wrecks | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Helping Hands | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Come Back, Miss Pipps | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Wedding Worries | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1941 | Main Street on the March! | Schulte Child | Short film; uncredited |

| 1942 | Melodies Old and New | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1942 | Going to Press | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1942 | Mokey | Daniel "Mokey" Delano | Credited as Bobby Blake |

| 1942 | Don't Lie | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1942 | Kid Glove Killer | Boy in Car | Uncredited |

| 1942 | Surprised Parties | Mickey | Short film; credited as Mickey Gubitosi |

| 1942 | Doin' Their Bit | Mickey | Short film; uncredited |

| 1942 | Rover's Big Chance | Mickey | Short film |

| 1942 | Mighty Lak a Goat | Mickey | Short film |

| 1942 | Unexpected Riches | Mickey | Short film |

| 1942 | Andy Hardy's Double Life | "Tooky" Stedman | |

| 1942 | China Girl | Chandu | |

| 1943 | Benjamin Franklin, Jr. | Mickey | Short film |

| 1943 | Family Troubles | Mickey | Short film |

| 1943 | Slightly Dangerous | Boy on Porch | Uncredited |

| 1943 | Calling All Kids | Mickey | Short film |

| 1943 | Farm Hands | Mickey | Short film |

| 1943 | Election Daze | Mickey | Short film |

| 1943 | Salute to the Marines | Junior Carson | Uncredited |

| 1943 | Little Miss Pinkerton | Mickey | Short film |

| 1943 | Three Smart Guys | Mickey | Short film |

| 1943 | Lost Angel | Jerry | |

| 1944 | Radio Bugs | Mickey | Short film |

| 1944 | Tale of a Dog | Mickey | Short film |

| 1944 | Dancing Romeo | Mickey | Short film |

| 1944 | Tucson Raiders | Little Beaver | |

| 1944 | Meet the People | Jimmy Smith | Uncredited |

| 1944 | Marshal of Reno | Little Beaver | |

| 1944 | The Seventh Cross | Small Boy | Uncredited |

| 1944 | The San Antonio Kid | Little Beaver | |

| 1944 | The Big Noise | Egbert Hartley | |

| 1944 | Cheyenne Wildcat | Little Beaver | |

| 1944 | The Woman in the Window | Dickie Wanley | Uncredited |

| 1944 | Vigilantes of Dodge City | Little Beaver | |

| 1944 | Sheriff of Las Vegas | Little Beaver | |

| 1945 | Great Stagecoach Robbery | Little Beaver | |

| 1945 | Pillow to Post | Wilbur | |

| 1945 | The Horn Blows at Midnight | Junior Poplinski | |

| 1945 | Lone Texas Ranger | Little Beaver | |

| 1945 | Phantom of the Plains | Little Beaver | |

| 1945 | Marshal of Laredo | Little Beaver | |

| 1945 | Colorado Pioneers | Little Beaver | |

| 1945 | Dakota | Little Boy | |

| 1945 | Wagon Wheels Westward | Little Beaver | |

| 1946 | A Guy Could Change | Alan Schroeder | |

| 1946 | California Gold Rush | Little Beaver | |

| 1946 | Sheriff of Redwood Valley | Little Beaver | |

| 1946 | Home on the Range | Cub Garth | |

| 1946 | Sun Valley Cyclone | Little Beaver | |

| 1946 | In Old Sacramento | Newsboy | |

| 1946 | Conquest of Cheyenne | Little Beaver | |

| 1946 | Santa Fe Uprising | Little Beaver | |

| 1946 | Out California Way | Danny McCoy | |

| 1946 | Stagecoach to Denver | Little Beaver | |

| 1946 | Humoresque | Paul Boray as a Child | |

| 1947 | Vigilantes of Boomtown | Little Beaver | |

| 1947 | Homesteaders of Paradise Valley | Little Beaver | |

| 1947 | Oregon Trail Scouts | Little Beaver | |

| 1947 | Rustlers of Devil's Canyon | Little Beaver | |

| 1947 | Marshal of Cripple Creek | Little Beaver | |

| 1947 | The Return of Rin Tin Tin | Paul the Refugee Lad | |

| 1947 | The Last Round-up | Mike Henry | |

| 1948 | The Treasure of the Sierra Madre | Mexican Boy Selling Lottery Tickets | Uncredited |

| 1950 | Black Hand | Enrico, Naples Bus Boy | Uncredited |

| 1950 | The Black Rose | Mahmoud | |

| 1952 | Apache War Smoke | Luis Herrera | |

| 1953 | Treasure of the Golden Condor | Stable Boy | Uncredited |

| 1953 | The Veils of Bagdad | Beggar Boy | |

| 1956 | Screaming Eagles | Pvt. Hernandez | |

| 1956 | The Rack | Italian soldier | Uncredited |

| 1956 | Rumble on the Docks | Chuck | |

| 1957 | Three Violent People | Rafael Ortega | |

| 1957 | The Tijuana Story | Enrique Acosta Mesa | |

| 1958 | The Beast of Budapest | Karolyi | |

| 1958 | Revolt in the Big House | Rudy Hernandez | |

| 1959 | Pork Chop Hill | Pvt. Velie | |

| 1959 | Battle Flame | Cpl. Jake Pacheco | |

| 1959 | The Purple Gang | William Joseph "Honeyboy" Willard | |

| 1961 | Town Without Pity | Corporal Jim Larkin | |

| 1963 | PT 109 | Charles "Bucky" Harris | |

| 1965 | The Greatest Story Ever Told | Simon the Zealot | |

| 1966 | This Property Is Condemned | Sidney | |

| 1967 | In Cold Blood | Perry Smith | |

| 1969 | Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here | Willie Boy | |

| 1972 | Ripped Off | Teddy "Cherokee" Wilson | |

| 1972 | Corky | Corky | |

| 1973 | Electra Glide in Blue | Officer John Wintergreen | |

| 1974 | Busting | Farrell | |

| 1980 | Coast to Coast | Charles Callahan | |

| 1981 | Second-Hand Hearts | Loyal Muke | |

| 1995 | Money Train | Donald Patterson | |

| 1997 | Lost Highway | The Mystery Man | Final film role |

9.2. Television

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok | Rain Cloud | Episode: "The Professor's Daughter" |

| 1953 | Fireside Theatre | Johnny | Episode: "Night in the Warehouse" |

| 1953 | The Cisco Kid | Davy / Alfredo | 2 episodes |

| 1956 | The Roy Rogers Show | Unknown character | Episode: "Paleface Justice" |

| 1956-1958 | Broken Arrow | Viklai / Machogee / Young Apache Warrior | 3 episodes |

| 1957 | Official Detective | Al Madsen | Episode: "The Hostages" |

| 1957 | Men of Annapolis | Ed | Episode: "The White Hat" |

| 1957 | 26 Men | Tobe Hackett | Episode: "Trade Me Deadly" |

| 1957 | Whirlybirds | Jose | Episode: "The Runaway" |

| 1957 | The Court of Last Resort | Tomas Mendoza | Episode: "The Tomas Mendoza Case" |

| 1958 | The Millionaire | Clark Davis | Episode: "The John Richards Story" |

| 1958 | The Restless Gun | Lupe Sandoval | Episode: "Thunder Valley" |

| 1958 | The Californians | Cass | Episode: "The Long Night" |

| 1959 | Black Saddle | Wayne Robinson | Episode: "Client: Robinson" |

| 1959 | Playhouse 90 | Unknown character | Episode: "A Trip to Paradise" |

| 1959 | Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre | CSA Cpl. Michael Bers | Episode: "Heritage" |

| 1960 | The Rebel | Virgil Moss | Episode: "He's Only a Boy" |

| 1960 | Alcoa Presents: One Step Beyond | Tom | Episode: "Gyspy" |

| 1960-1962 | Have Gun - Will Travel | Lauro / Jessie May Turnbow / Smollet | 3 episodes |

| 1961 | Bat Masterson | Bill-Bill MacWilliams | Episode: "No Amnesty for Death" |

| 1961 | Wagon Train | Johnny Kamen | Episode: "The Joe Muharich Story" |

| 1961 | Naked City | Knox Maquon | 2 episodes |

| 1961 | Laramie | Lame Wolf | Episode: "Wolf Club" |

| 1961-1962 | Straightaway | Chu Chu | 2 episodes |

| 1962 | Ben Casey | Jesse Verdugo | Episode: "Imagine a Long Bright Corridor" |

| 1962 | Cain's Hundred | Rick Carter | Episode: "A Creature Lurks in Ambush" |

| 1962 | The New Breed | Bobby Madero | Episode: "My Brother's Keeper" |

| 1963-1964 | The Richard Boone Show | Various | 14 episodes |

| 1965 | Slattery's People | Jerry Leon | Episode: "Question: Does Nero Still at Ringside Sit?" |

| 1965 | The Trials of O'Brien | Joe Rooney | Episode: "Bargain Day on the Street of Regret" |

| 1965 | Rawhide | Max Gufler / Hap Johnson | 2 episodes |

| 1965-1966 | The F.B.I. | Junior / Pete Cloud | 2 episodes |

| 1966 | Twelve O'Clock High | Lt. Johnny Eagle | Episode: "A Distant Cry" |

| 1966 | Death Valley Days | Billy the Kid | Episode: "The Kid from Hell's Kitchen" |

| 1975-1978 | Baretta | Detective Anthony Vincenzo "Tony" Baretta | 82 episodes |

| 1977 | 29th Primetime Emmy Awards | Co-host | With Angie Dickinson |

| 1981 | The Big Black Pill | Joe Dancer | Television film |

| 1981 | The Monkey Mission | Joe Dancer | Television film |

| 1981 | Of Mice and Men | George Milton | Television film |

| 1982 | Saturday Night Live | Host | Episode: "Robert Blake/Kenny Loggins" |

| 1983 | Blood Feud | Jimmy Hoffa | Miniseries |

| 1983 | Murder 1, Dancer 0 | Joe Dancer | Television film |

| 1985 | Hell Town | Noah "Hardstep" Rivers | 13 episodes |

| 1985 | Heart of a Champion: The Ray Mancini Story | Lenny Mancini | Television film |

| 1993 | Judgment Day: The John List Story | John List | Television film |