1. Overview

Richard Hooker (March 1554 - 3 November 1600) was a prominent English priest and theologian within the Church of England, recognized as one of the most significant English theologians of the sixteenth century. He is widely regarded as a foundational figure in Anglican theology and political philosophy, known for his emphasis on reasoned discourse, institutional balance, and the accommodation of diverse viewpoints. His work provided a theological method that harmoniously combined the claims of revelation, reason, and tradition, significantly influencing the Caroline Divines of the seventeenth century and later generations of Anglican thinkers.

Hooker is traditionally seen as the originator of the Anglican via media, a middle way between Protestantism and Catholicism. However, a growing number of scholars argue that he remained within the mainstream of Reformed theology of his era, primarily seeking to counter Puritan extremists rather than moving the Church of England away from Protestantism. As an influential apologist, Hooker publicly debated with Walter Travers, a leading Calvinist, regarding the necessity for the Church of England to adhere to patterns established by John Calvin. A central point of contention was the role of the Bible in determining ecclesiastical policy. Travers contended that the Bible prescribed a presbyterian model for church governance, while Hooker maintained that the Bible offered no specific model, instead suggesting that natural and positive laws should guide church administration. His views on salvation, which allowed for the possibility of salvation for those who did not fully grasp or accept the doctrine of justification by faith, were seen as a challenge to strict Calvinist interpretations, reflecting his inclusive theological approach.

2. Early Life and Education

Richard Hooker was born in March 1554, around Easter Sunday, in the village of Heavitree near Exeter, Devon, England. His family, though respectable, was neither noble nor wealthy. His uncle, John Hooker, was a successful figure who served as the chamberlain of Exeter.

Through his uncle's connections, Richard received support from another Devon native, John Jewel, who was then the Bishop of Salisbury. Bishop Jewel recognized Hooker's potential and arranged for his admission to Corpus Christi College, Oxford, also funding his education. Hooker excelled academically, becoming a fellow of the college in 1577. In 1580, he was temporarily deprived of his fellowship due to "contentiousness" after campaigning for the losing candidate, Rainoldes, in a contested election for the college presidency. However, he regained his fellowship once Rainoldes eventually assumed the post.

3. Ordination and Early Career

On 14 August 1579, Richard Hooker was ordained as a priest by Edwin Sandys, who at that time served as the Bishop of London. Sandys subsequently appointed Hooker as a tutor to his son, Edwin. During this period, Hooker also instructed George Cranmer, who was the great-nephew of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

In 1584, Hooker was appointed rector of St. Mary's Drayton Beauchamp in Buckinghamshire. However, it is believed that he never actually resided there.

4. London Ministry and Theological Debates

In 1581, Richard Hooker was invited to preach at St Paul's Cross in London, an event that marked his emergence as a public figure. His sermon on this occasion diverged from Puritan theories of predestination, causing offense among Puritan factions. This period saw him drawn into the broader theological debates of the time, influenced by figures such as Edwin Sandys and George Cranmer. The Puritans had previously issued an "Admonition to Parliament" and "A view of Popish Abuses," initiating a prolonged theological dispute that extended beyond the century. John Whitgift, who would soon become Archbishop of Canterbury, responded to the Puritan critiques, and Thomas Cartwright subsequently reacted to Whitgift's reply, further fueling the controversy.

In 1585, Hooker was appointed Master of the Temple in London, possibly as a compromise candidate supported by both Lord Burleigh and Whitgift. At the Temple, Hooker soon found himself in public conflict with Walter Travers, a leading Puritan and lecturer at the Temple. Their dispute stemmed partly from Hooker's earlier sermon at Paul's Cross and, more significantly, from Hooker's argument that salvation was possible even for some Roman Catholics. Travers accused Hooker of advocating doctrines favorable to the Church of Rome. The core of their debate revolved around how the Bible should be interpreted and applied in determining ecclesiastical policy. Travers asserted that the Bible explicitly taught a presbyterian model of church governance, while Hooker argued that the Scriptures did not prescribe any single, unalterable form of church government, but rather suggested that natural and positive laws should inform ecclesiastical administration. This controversy concluded abruptly in March 1586 when Archbishop Whitgift silenced Travers, a decision strongly supported by the Privy Council. Despite their public disagreements, Hooker and Travers reportedly maintained a personal friendship.

Around this time, Hooker began writing his monumental work, Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, intended as a comprehensive critique of Puritanism and their attacks on the Church of England, particularly the Book of Common Prayer. In 1591, to allow him to focus on his writing, Hooker left the Temple and was granted the living of St Andrew's, Boscombe, Wiltshire. Although he primarily resided in London, he also spent time in Salisbury, where he served as subdean of Salisbury Cathedral and utilized its library for his studies. The first four volumes of his major work were published in 1593, with financial support from Edwin Sandys. The remaining volumes were reportedly held back for further revision.

5. Major Works

Richard Hooker's literary output, though not extensive beyond his magnum opus, is primarily divided into his seminal work, Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, and a few other significant writings, including sermons that arose from his theological controversies.

5.1. Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity

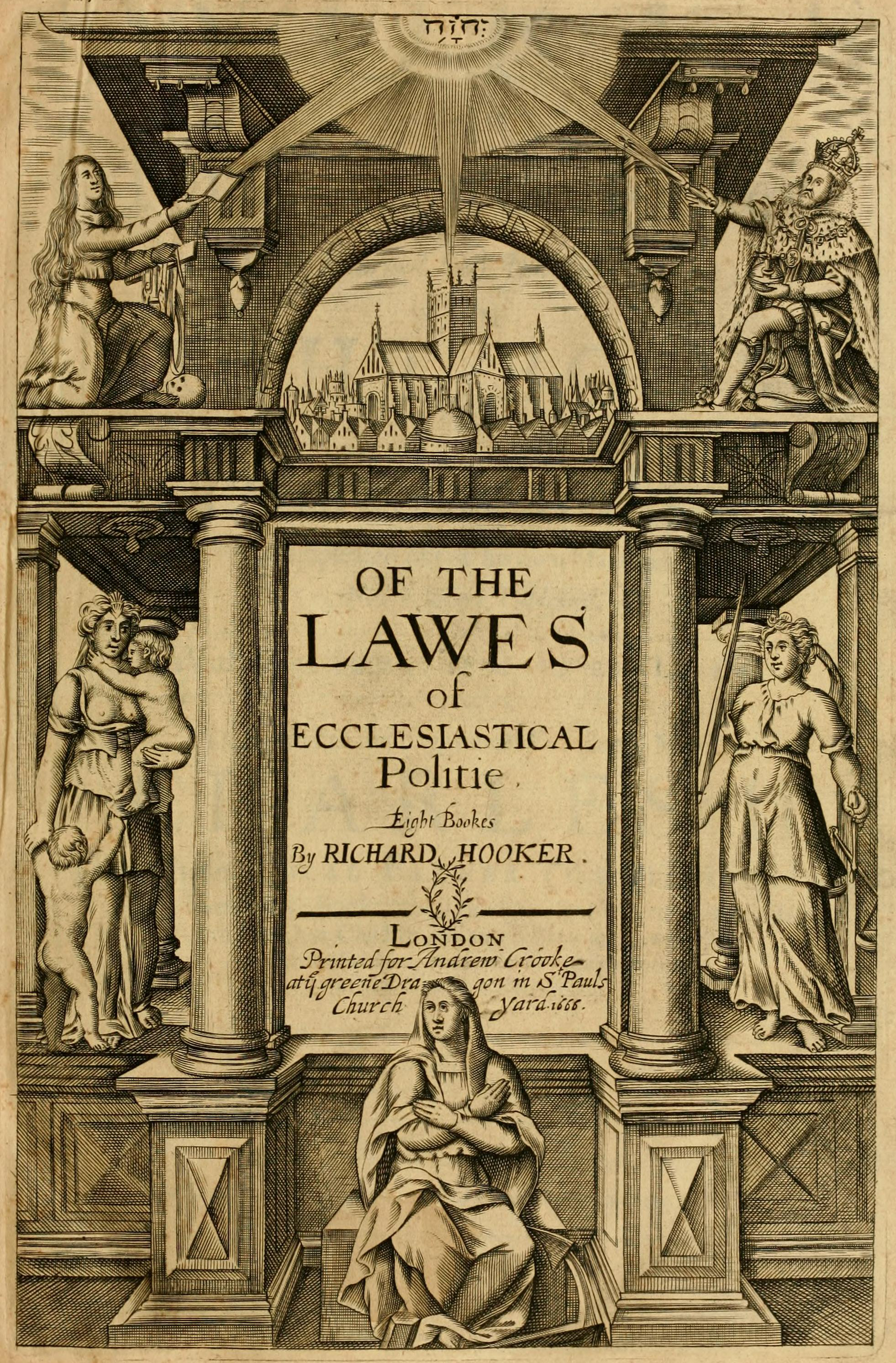

Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (originally spelled Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie) is Richard Hooker's most renowned work and is considered a landmark in English philosophy and theology. The first four books were published in 1593 (some sources indicate 1594), followed by the fifth book in 1597. The final three books were published posthumously and their authorship is debated among scholars, with some suggesting they may not entirely be Hooker's own work.

Structurally, the Laws serves as a meticulously crafted response to the fundamental principles of Puritanism, particularly as articulated in the "Admonition to Parliament" and Thomas Cartwright's subsequent writings. Hooker directly addressed several key Puritan claims:

- That Scripture alone should govern all human conduct.

- That Scripture prescribes an unalterable form of Church government.

- That the English Church was corrupted by Roman Catholic orders, rites, and ceremonies.

- That the law was corrupt for not allowing lay elders.

- That there should be no bishops in the Church.

Beyond merely refuting Puritan arguments, the Laws presents a continuous and coherent philosophy and theology that aligns with the Anglican Book of Common Prayer and the traditional aspects of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. As C. S. Lewis noted, Hooker introduced a strategic depth to theological debate, rendering the Puritan position vulnerable through his extensive arguments in the early books of the work.

The primary focus of this massive work is the proper governance of churches, or "polity." While Puritans advocated for a reduction in the status of clergy and ecclesiasticism, Hooker sought to articulate the most effective methods for organizing churches. A central underlying issue was the position of Queen Elizabeth I as the Supreme Governor of the Church. If doctrine were not to be settled by established authorities, and if Martin Luther's argument for the priesthood of all believers were extended to its extreme of government by the Elect, then the monarch's role as church governor would become intolerable. Conversely, if the monarch was divinely appointed as the church's governor, then local parishes interpreting doctrine independently would be equally unacceptable.

In political philosophy, Hooker is particularly remembered for his comprehensive account of law and the origins of government, detailed in Book One of the Laws. Drawing extensively on the legal thought of Thomas Aquinas, Hooker distinguishes seven forms of law:

- Eternal law:** God's eternal purpose observed in all His works.

- Celestial law:** God's law governing angels.

- Nature's law:** The part of God's eternal law that governs natural objects.

- Law of reason:** Dictates of Right Reason that normatively govern human conduct.

- Human positive law:** Rules created by human lawmakers for the ordering of civil society.

- Divine law:** Rules laid down by God, knowable only through special revelation.

- Ecclesiastical law:** Rules for the governance of a church.

Following Aristotle, whom he frequently quoted, Hooker believed that humans possess a natural inclination to live in society. He argued that governments are founded upon both this inherent social instinct and the express or implied consent of the governed. The Laws is celebrated not only for its monumental contribution to Anglican thought but also for its profound influence on the development of theology, political theory, and English prose.

5.2. Learned Discourse of Justification and Other Writings

Hooker's sermon from 1585, A Learned Discourse of Justification, played a pivotal role in triggering Walter Travers' public criticism and appeal to the Privy Council. Travers accused Hooker of preaching doctrines that favored the Church of Rome. In this discourse, Hooker meticulously outlined the differences between his views and those of Rome, particularly emphasizing that Rome attributed to human works "a power of satisfying God for sin." For Hooker, good works were not a means of earning salvation but rather a necessary expression of thanksgiving for unmerited justification bestowed by a merciful God.

While staunchly defending the Protestant doctrine of justification by faith, Hooker put forth a more inclusive argument: that even those who did not fully comprehend or accept this specific doctrine could still be saved by God's grace. This perspective reflected his belief that Christians, including Roman Catholics, should seek unity rather than division. In this work, Hooker also articulated the classic ordo salutis (order of salvation), recognizing the distinction between justification and sanctification as two forms of righteousness, while simultaneously underscoring the vital role of the sacraments in the process of justification. His approach to this complex theological topic is often cited as a classic example of the Anglican via media.

Beyond Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, Hooker's other writings are few. They generally fall into three categories: those directly related to the Temple Controversy with Travers (including three sermons), those connected with the final stages of writing the later books of the Laws, and a collection of miscellaneous sermons (four complete and three fragments).

6. Theology and Philosophy

Richard Hooker's theological and philosophical contributions were instrumental in shaping Anglican thought, distinguishing it from both Roman Catholicism and radical Protestantism. His ideas emphasize a balanced approach to faith, reason, and governance, reflecting a commitment to moderation and inclusivity.

6.1. Views on Justification, Salvation, and Worship

Hooker's theological positions on justification and salvation were nuanced, seeking a middle ground that affirmed Protestant principles while allowing for broader theological charity. He firmly upheld the doctrine of justification by faith, asserting that salvation is a gift of God's grace, not earned by human merit. However, he also argued that good works are a necessary expression of gratitude for this unmerited justification. Crucially, Hooker believed that God's mercy extended even to those who might not fully grasp or explicitly accept the doctrine of justification by faith, suggesting a more expansive view of salvation than many of his Puritan contemporaries. He distinguished between justification (being declared righteous by God) and sanctification (the process of becoming holy), while also highlighting the significant role of the sacraments in the believer's journey of justification.

Regarding public worship and church practices, Hooker maintained that while some aspects of worship are determined by God's explicit word, not every detail of liturgical practice is divinely prescribed. He contended that for matters not explicitly defined in Scripture, the Church has the discretion and freedom to establish practices that are orderly, edifying, and appropriate for the context. This view allowed for flexibility and adaptation in worship, contrasting with the Puritan demand for strict adherence to perceived biblical mandates for every aspect of church life.

6.2. Views on Law and Government

Hooker's political philosophy, particularly his theories on the nature of law and the origins of government, is a cornerstone of his intellectual legacy. Drawing heavily from the legal and philosophical traditions of Thomas Aquinas, Hooker posited a comprehensive framework of law that governs the universe and human society. He identified seven distinct forms of law, ranging from the eternal law of God to human positive law and ecclesiastical law.

He argued that human beings are naturally inclined to live in society, a concept he derived from Aristotle. Consequently, governments, according to Hooker, are founded upon both this inherent social instinct and the explicit or implied consent of the governed. This emphasis on consent as a basis for legitimate governance was a significant contribution to political thought, influencing later thinkers such as John Locke. Hooker's views underscored the importance of reason and natural law in the establishment and operation of civil society, advocating for a system where authority is balanced by the principles of justice and the common good.

6.3. Adaptation of Scholasticism and the Via Media

Richard Hooker's intellectual method involved a distinctive adaptation of Scholasticism, particularly the thought of Thomas Aquinas, in a latitudinarian manner. He argued that aspects of church organization, much like political organization, fall into the category of "things indifferent" to God. This meant that minor doctrinal issues or procedural matters were not fundamental to the salvation or damnation of a soul, but rather served as frameworks or conveniences for the moral and religious life of the believer.

Hooker contended that there could be both good and bad monarchies, democracies, and church hierarchies; what truly mattered was the piety and loyalty of the people within those structures. While affirming that authority was divinely commanded through the Bible and the traditions of the early church, he stressed that such authority must be grounded in piety and reason, rather than merely automatic investiture or customary obedience. He believed that authority, even if perceived as flawed, must generally be obeyed, but that it could and should be remedied by right reason and the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Notably, Hooker affirmed that the power and propriety of bishops need not be absolute in every instance, and their functions could, in principle, be subject to review or even revocation. This measured approach allowed him to avoid the extreme claims of some High church proponents, solidifying his role in shaping the Anglican via media by balancing Scripture, reason, and tradition.

7. Personal Life and Marriage

Details concerning Richard Hooker's personal life are primarily derived from the biography written by Izaak Walton. According to Walton, Hooker made a "fatal mistake" in 1588 by marrying Jean Churchman, the daughter of his landlady, John Churchman, a distinguished London merchant. However, modern scholars, including Christopher Morris, have characterized Walton as an "unreliable gossip" who often shaped his subjects to fit a preconceived narrative. Despite Walton's portrayal, other accounts suggest that Hooker was "well treated and considerably assisted by John Churchman and his wife." Hooker appears to have lived intermittently with the Churchman family until 1595. He was survived by his wife and their four daughters.

8. Later Years and Death

In 1595, Richard Hooker became the rector of the parishes of St. Mary the Virgin in Bishopsbourne and St. John the Baptist in Barham, both located in Kent. He subsequently left London to devote himself fully to his writing. In 1597, he published the fifth book of his monumental work, Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, which is notably longer than the first four books combined.

Richard Hooker died on 3 November 1600, at his rectory in Bishopsbourne. He was laid to rest in the chancel of the church. His will included a specific provision: "Item, I give and bequeth three pounds of lawful English money towards the building and making of a newer and sufficient pulpitt in the p'sh of Bishopsbourne." This pulpit can still be seen in Bishopsbourne church today, alongside a statue commemorating him. In 1632, a monument was erected there by William Cowper, which famously described Hooker as "judicious."

9. Legacy and Influence

Richard Hooker's legacy is profound and enduring, particularly in the development of Anglicanism and political philosophy. King James I is famously quoted by Hooker's biographer, Izaak Walton, as remarking on Hooker's writing: "I observe there is in Mr. Hooker no affected language; but a grave, comprehensive, clear manifestation of reason, and that backed with the authority of the Scriptures, the fathers and schoolmen, and with all law both sacred and civil." This assessment encapsulates Hooker's distinctive approach, which emphasized the harmonious integration of Scripture, reason, and tradition.

His emphasis on reasoned discourse, tolerance, and the judicious application of law significantly influenced the trajectory of Anglican theology, establishing a balanced and inclusive identity for the Church of England. Furthermore, Hooker's political philosophy had a substantial impact on subsequent thinkers, most notably John Locke. Locke extensively quoted Hooker in his Second Treatise of Civil Government, drawing heavily on Hooker's natural-law ethics and his staunch defense of human reason as the basis for government and individual rights. Hooker's articulation of government originating from the consent of the governed laid crucial groundwork for later theories of social contract.

Frederick Copleston noted that Hooker's moderation and civil style of argument were particularly remarkable given the intense religious atmosphere of his time. His ability to engage in profound theological and philosophical debate without resorting to extremism cemented his reputation as a judicious and foundational figure in English intellectual history. In recognition of his contributions, Richard Hooker is celebrated with a lesser festival in the Church of England and other parts of the Anglican Communion on 3 November.