1. Early life

The early life of the individual who would become the Public Universal Friend, born Jemima Wilkinson, was shaped by their family's Quaker heritage, their upbringing in Rhode Island, and their evolving religious affiliations that led to a period of significant personal stress.

1.1. Childhood and Education

The individual who would later become known as the Public Universal Friend was born on November 29, 1752, in Cumberland, Rhode Island. This made them the eighth child of Amy (née Whipple) and Jeremiah Wilkinson, and the fourth generation of their family to reside in America. The child was named Jemima, after the biblical figure Jemima, one of Job's daughters.

The Friend's great-grandfather, Lawrence Wilkinson, had been an officer in the army of Charles I before emigrating from England around 1650 and becoming active in colonial government. Jeremiah Wilkinson, the Friend's father, was a cousin of Stephen Hopkins, who served as a longtime governor of the colony and was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Jeremiah attended traditional worship with the Society of Friends (the Quakers) at the Smithfield Meeting House. While early biographer David Hudson stated that Amy was also a Quaker member, later biographer Herbert Wisbey found no evidence for this, though he noted that Moses Brown said the child was "born such" due to Jeremiah's affiliation. Amy died in 1764, when Wilkinson was 12 or 13 years old, shortly after giving birth to her twelfth child.

Wilkinson was described as having fine black hair and eyes, and was noted from an early age for being strong and athletic. The Friend became an adept equestrian in childhood and remained so in adulthood, favoring spirited horses and ensuring that animals received good care. An avid reader, the Friend could quote long passages of the Bible and prominent Quaker texts from memory. Little else is reliably known about Wilkinson's childhood. Some early accounts, such as Hudson's, depicted Wilkinson as fond of fine clothes and averse to labor, but there is no contemporaneous evidence supporting this. Biographer Paul Moyer suggests that such descriptions may have been invented to fit a common narrative of the time, which posited that individuals experiencing dramatic religious awakenings were formerly profligate sinners.

1.2. Religious Background and Early Activities

In the mid-1770s, Wilkinson began attending meetings in Cumberland with New Light Baptists. This group had formed as part of the Great Awakening and emphasized individual spiritual enlightenment. As a result, Wilkinson stopped attending meetings of the Society of Friends. This led to disciplinary action in February 1776, and by August of that year, Wilkinson was disowned by the Smithfield Meeting. At the same time, Wilkinson's sister Patience was dismissed for having an illegitimate child, and brothers Stephen and Jeptha had been dismissed by the pacifistic Society in May 1776 for training for military service. Amid these family disturbances and the broader turmoil of the American Revolutionary War, and feeling dissatisfied with the New Light Baptists while being shunned by mainstream Quakers, Wilkinson experienced significant stress in 1776.

2. Becoming the Public Universal Friend

The transformative period in Jemima Wilkinson's life occurred in 1776, following a severe illness, after which the Friend claimed to have undergone a spiritual death and reanimation. This experience led to the adoption of a new identity as a genderless evangelist, known as the Public Universal Friend.

2.1. Illness and Spiritual Experience

In October 1776, Wilkinson contracted an epidemic disease, most likely typhus, which left them bedridden with a high fever and near death. The family summoned a doctor from Attleboro, about 6 mile away, and neighbors maintained a death-watch throughout the nights. After several days, the fever broke.

The Friend later recounted that Wilkinson had died during this illness, receiving profound revelations from God through two archangels. These celestial beings proclaimed, "Room, Room, Room, in the many Mansions of eternal glory for Thee and for everyone." The Friend further asserted that Wilkinson's soul had ascended to heaven, and the body had been reanimated with a new spirit, specifically charged by God with preaching His word. This new spiritual entity was the "Publick Universal Friend," a name the Friend described using the words of Isaiah 62:2 from the King James Version of the Bible: "a new name which the mouth of the Lord hath named." This designation also referenced the term "Public Friends" used by the Society of Friends for members who traveled to preach. While some 18th and 19th-century writers claimed Wilkinson briefly died or even dramatically rose from a coffin, and others suggested the illness was feigned, accounts from the doctor and other witnesses confirm the illness was real but do not state that Wilkinson died.

2.2. Establishing a New Identity

From the moment of this spiritual transformation, the Friend refused to answer to "Jemima Wilkinson," ignoring or chastising anyone who insisted on using the birth name. So steadfast was this refusal that the Friend had friends hold real estate in trust to avoid seeing the name on deeds and titles. Even when a lawyer insisted that the Friend's will identify the subject as "the person who before the year one thousand seven hundred & seventy seven was known & called by the name of Jemima Wilkinson but since that time as the Universal Friend," the preacher refused to sign that name, only making an X which others witnessed. This led some writers to mistakenly believe the evangelist was illiterate. When visitors inquired if "Jemima Wilkinson" was the name of the person they were addressing, the Friend would simply quote Luke 23:3: "thou sayest it."

Identifying as neither male nor female, the Friend requested not to be referred to with gendered pronouns. Followers largely respected these wishes, referring only to "the Public Universal Friend" or shorter forms like "the Friend" or "P.U.F." Many even avoided gender-specific pronouns in their private diaries, though some others used he. When directly asked about their gender, the preacher famously replied, "I am that I am," and similarly responded to a man who criticized their manner of dress, adding, "there is nothing indecent or improper in my dress or appearance; I am not accountable to mortals."

The Friend's attire was perceived as either androgynous or masculine. They typically wore long, loose clerical robes, most often black, and a white or purple kerchief or cravat around the neck, similar to men of the era. Indoors, the preacher did not wear a hair-cap, unlike women of the time, and outdoors, they wore broad-brimmed, low-crowned beaver hats, a style favored by Quaker men. Descriptions of the Friend's voice varied, with some hearers describing it as "clear and harmonious," or speaking "with ease and facility," and "clearly, though without elegance." Others, however, characterized it as "grum and shrill," or like a "kind of croak, unearthly and sepulchral." The Friend was generally described as moving easily, freely, and modestly, and Ezra Stiles noted them as "decent & graceful & grave."

3. Beliefs, Preaching, and the Society of Universal Friends

The Public Universal Friend's ministry was characterized by a distinct theology largely aligned with Quakerism, fervent itinerant preaching, and the establishment of a unique religious community known as the Society of Universal Friends.

3.1. Theology and Religious Teachings

The Friend began traveling and preaching throughout Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, accompanied by siblings Stephen, Deborah, Elizabeth, Marcy (sometimes spelled Mercy), and Patience, all of whom had also been disowned by the Society of Friends. Initially, the Public Universal Friend preached that people needed to repent of their sins and be saved before an imminent Day of Judgment. According to Abner Brownell, the preacher predicted that the fulfillment of some prophecies from the Book of Revelation would begin around April 1780, 42 months after the Universal Friend commenced preaching. The New England's Dark Day in May 1780 was subsequently interpreted as a fulfillment of this prediction. Some later followers, such as Sarah Richards and James Parker, even believed themselves to be the two witnesses mentioned in Revelation and temporarily wore sackcloth in accordance with this belief.

During worship meetings, which were initially held outdoors or in borrowed meeting houses, the Friend did not use a Bible but preached long sections of the scriptures from memory. The meetings attracted large audiences, including some who formed a congregation known as "Universal Friends," making the Friend the first native-born American to found a religious community. These followers included roughly equal numbers of women and men, predominantly under 40 years of age. Most came from Quaker backgrounds, although mainstream Quakers actively discouraged and disciplined their members for attending meetings with the Friend. Mainstream Quakers, such as William Savery, disapproved of the Friend, viewing their actions as "pride and ambition to distinguish [them]self from the rest of mankind." In contrast, Free Quakers, who had been disowned by the main Society of Friends for their participation in the American War of Independence, were particularly sympathetic to the Universal Friends and opened their meeting houses to them, appreciating that many of the Friend's family members and followers had also sympathized with the Patriot cause.

By the mid-1780s, popular newspapers and pamphlets extensively covered the Friend's sermons, with several Philadelphia newspapers being particularly critical. This negative coverage fomented enough opposition that noisy crowds gathered outside every place the preacher stayed or spoke in 1788. Most papers focused more on the preacher's ambiguous gender than on their theology, which was broadly similar to the teachings of most Quakers. One person who heard the Friend in 1788 remarked that "from common report I expected to hear something out of the way in doctrine, which is not the case, in fact [I] heard nothing but what is common among preachers" in mainstream Quaker churches. The Friend's theology was so similar to that of mainstream Quakers that one of the two published works associated with the preacher was a plagiarism of Isaac Penington's Works. According to Abner Brownell, the Friend believed that the sentiments would have greater resonance if republished under the name of the Universal Friend. The Universal Friends also adopted language similar to the Society of Friends, using thee and thou instead of the more formal singular you.

The Public Universal Friend rejected the concepts of predestination and election, holding that anyone, regardless of gender, could gain access to God's light. They believed that God spoke directly to individuals, who possessed free will to choose their actions and beliefs, and embraced the possibility of universal salvation.

3.2. Social Views and Activities

The Friend was a staunch advocate for the abolition of slavery, successfully persuading followers who held enslaved people to free them. Several members of the congregation of Universal Friends were black, and they served as witnesses for manumission papers. The Friend preached humility and hospitality towards everyone, keeping religious meetings open to the public and housing and feeding visitors, including those who came merely out of curiosity, as well as indigenous peoples, with whom the preacher generally maintained a cordial relationship. The Friend possessed few personal belongings, mostly gifts from followers, and never held any real property except in trust.

The Friend preached sexual abstinence and generally disfavored marriage, but did not consider celibacy mandatory. They accepted marriage, especially viewing it as preferable to breaking abstinence outside of wedlock. While most followers did marry, the proportion who remained unmarried was significantly higher than the national average of the time. The preacher also maintained that women should "obey God rather than men." Among the most committed followers were approximately four dozen unmarried women known as the Faithful Sisterhood, who took on leading roles typically reserved for men. The proportion of households headed by women in the Society's settlements, at 20%, was significantly higher than in surrounding areas.

Around 1785, the Friend met Sarah and Abraham Richards. Their unhappy marriage ended in 1786 with Abraham's death during a visit to the Friend. Sarah, along with her infant daughter, subsequently took up residence with the Friend, adopting a similarly androgynous hairstyle, dress, and mannerisms, as did a few other close female friends. Sarah came to be known as Sarah Friend. The Friend entrusted Richards with holding the Society's property in trust and dispatched her to preach in different parts of the country when the Friend was elsewhere. Richards played a significant role in planning and constructing the house where she and the preacher lived in the town of Jerusalem. Upon her death in 1793, she entrusted her child to the Friend's care.

In October 1794, the Friend and several followers dined with Thomas Morris (son of financier Robert Morris) in Canandaigua, at the invitation of Timothy Pickering. They then accompanied Pickering to talks with the Iroquois aimed at producing the Treaty of Canandaigua. With Pickering's permission and an interpreter, the Friend delivered a speech to the US government officials and Iroquois chiefs about "the Importance of Peace & Love," which was well-received by the Iroquois.

4. Settlement and Legal Issues

The Society of Universal Friends faced significant challenges in establishing and maintaining their settlements in western New York, including complex land disputes and legal persecution.

4.1. Establishing Settlements in Western New York

In the mid-1780s, the Universal Friends began planning a town for themselves in western New York. By late 1788, vanguard members of the Society had established a settlement in the Genesee River area. By March 1790, the settlement was sufficiently prepared for the rest of the Universal Friends to join, making it the largest non-Native community in western New York at that time.

However, problems soon arose. In 1791, James Parker spent three weeks petitioning the governor and land office of New York on behalf of the Society to secure a title to the land the Friends had settled. While most of the buildings and improvements made by the Universal Friends were initially east of the Preemption Line and thus within New York, a resurvey of the line in 1792 revealed that at least 25 homes and farms were now west of it, outside the area granted by New York. Residents were consequently forced to repurchase their lands from the Pulteney Association. The town, which had been known as the Friend's Settlement, therefore came to be called The Gore.

Furthermore, these lands were part of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase tract, which had been defaulted on and subsequently resold to financier Robert Morris, and then to the Pulteney Association, a group of absentee British speculators. Each change of hands drove prices higher, as did an influx of new settlers attracted by the Society's improvements to the area. The community struggled to secure a solid title to enough land for all its members, leading some to depart. Others, including James Parker and William Potter, sought to profit by taking ownership of the land for themselves. To address the issue of land scarcity, members of the Society of Universal Friends secured some alternative sites. Abraham Dayton acquired a large area of land in Canada from Governor John Graves Simcoe, although Sarah Richards ultimately persuaded the Friend not to relocate so far. Separately, in 1789, Thomas Hathaway and Benedict Robinson purchased a site along a creek they named Brook Kedron, which emptied into the Crooked Lake (now Keuka Lake). The new town that the Universal Friends began to build there eventually became known as Jerusalem.

4.2. Legal Disputes and Persecution

The land disputes and internal conflicts escalated dramatically in the fall of 1799. Judge William Potter, Ontario County magistrate James Parker, and several disillusioned former followers led multiple attempts to arrest the Friend on charges of blasphemy. Some historians argue that these attempts were primarily motivated by disagreements over land ownership and power within the community.

In one instance, an officer attempted to seize the Friend while they were riding with Rachel Malin in The Gore, but the Friend, a skilled horse-rider, managed to escape. Later, the officer and an assistant tried to arrest the preacher at home in Jerusalem, but the women of the house bravely drove the men off and tore their clothes. A third arrest attempt was meticulously planned by a posse of 30 men who surrounded the home after midnight, broke down the door with an ax, and intended to carry the preacher off in an oxcart. However, a doctor who had accompanied the posse intervened, stating that the Friend was in too poor a state of health to be moved. A deal was struck: the Friend agreed to appear before an Ontario County court in June 1800, on the condition that it would not be before Justice Parker. When the Friend appeared before the court, it ruled that no indictable offense had been committed, and the preacher was even invited to deliver a sermon to those in attendance.

5. Death and Legacy

The Public Universal Friend's later years were marked by declining health, culminating in their death in 1819. Following their passing, the Society of Universal Friends gradually declined, but the Friend's home and artifacts were preserved, contributing to a lasting historical and cultural legacy.

5.1. Later Life and Death

The Public Universal Friend's health had been in decline since the turn of the 19th century. By 1816, the preacher began to suffer from a painful edema, yet continued to receive visitors and deliver sermons. The Friend gave a final regular sermon in November 1818 and preached for the last time at the funeral of their sister, Patience Wilkinson Potter, in April 1819.

The Friend died on July 1, 1819. The congregation's death book recorded the event simply: "25 minutes past 2 on the Clock, The Friend went from here." In accordance with the Friend's wishes, only a regular meeting was held afterwards, with no formal funeral service. The body was placed in a coffin that featured an oval glass window set into its top. Four days after death, the coffin was interred in a thick stone vault within the cellar of the Friend's house. Several years later, the coffin was removed and buried in an unmarked grave, adhering to the preacher's preference for simplicity. Obituaries announcing the Friend's passing appeared in newspapers throughout the eastern United States.

5.2. Decline of the Society and Enduring Legacy

Following the Friend's death, close followers remained faithful, but their numbers gradually dwindled due to an inability to attract new converts amidst various legal and religious disagreements. The Society of Universal Friends eventually ceased to exist by the 1860s.

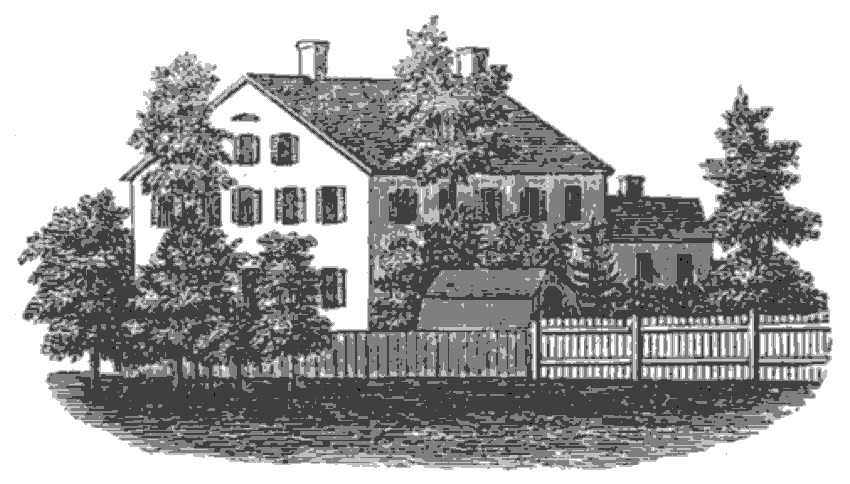

The Friend's Home and temporary burial chamber still stands in the town of Jerusalem and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is believed to be located on the same branch of Keuka Lake as the birthplace of Seneca chief Red Jacket, though his exact birthplace is disputed. The Yates County Genealogical and Historical Society's museums in Penn Yan exhibit the Friend's portrait, Bible, carriage, hat, saddle, and various documents from the Society of Universal Friends. As late as the 1900s, inhabitants of Little Rest, Rhode Island, referred to a species of solidago as Jemima weed, a name that arose because its appearance in the town coincided with the preacher's first visit to the area in the 1770s. The Friend and their followers were also pioneers in the region between Seneca and Keuka Lake lakes, with the Society of Universal Friends notably erecting a grain mill in Dresden.

6. Interpretations and Evaluation

The life and identity of the Public Universal Friend have been subject to diverse interpretations throughout history, reflecting evolving societal views on gender, religion, and social reform.

6.1. Historical Interpretations and Controversies

Although the Public Universal Friend identified as genderless, neither a man nor a woman, many early writers portrayed the preacher as a woman, often depicting them as either a fraudulent schemer who deceived and manipulated followers or as a pioneering leader who founded several towns where women were empowered to take on roles typically reserved for men. The view of the Friend as a fraudster was prevalent among many writers in the 18th and 19th centuries, notably perpetuated by David Hudson, whose hostile and inaccurate biography, written to influence a court case over the Society's land, remained influential for a long time. These writers circulated various myths, alleging that the Friend despotically bossed followers around, banished them for years, forced married followers to divorce, seized their property, or even attempted and failed to raise the dead or walk on water. However, there is no contemporaneous evidence to support these stories, and individuals who knew the Friend, including some who were never followers, stated that these rumors were false.

One notable fabricated story began at a 1787 meeting, after which Sarah Wilson claimed that Abigail Dayton attempted to strangle Wilson while she slept but mistakenly choked her bedmate, Anna Steyers. Steyers denied that anything had happened, and others present attributed Wilson's fears to a nightmare. Nevertheless, Philadelphia newspapers printed an embellished version of the accusation and several follow-ups, with critics alleging that the attack must have had the Friend's approval. The story eventually morphed into one in which the Friend (who was in a different state at the time) was accused of strangling Wilson. Another widespread allegation that sparked much hostility was the accusation that the preacher claimed to be Jesus. The Friend and the Universal Friends consistently denied this accusation.

6.2. Modern Reinterpretations and Gender Identity

Modern scholars have increasingly portrayed the Friend as a pioneering figure. Some, like Susan Juster and Catherine Brekus, view the Friend as an early figure in the history of women's rights. Others, including Scott Larson and Rachel Hope Cleves, explore the Friend's significance within transgender history. Historian Michael Bronski notes that while the Friend would not have been called transgender or transvestite "by the standards and the vocabulary" of their time, he has referred to the Friend as a "transgender evangelist." Juster describes the Friend as a "spiritual transvestite," suggesting that followers perceived the Friend's androgynous clothing as consistent with the genderless spirit they believed animated the preacher.

Juster and other scholars propose that, for their followers, the Friend may have embodied Paul's statement in Galatians 3:28 that "there is neither male nor female" in Christ. Catherine Wessinger, Brekus, and others argue that the Friend defied the conventional idea of gender as binary, natural, and essential or innate. However, Brekus and Juster also contend that the Friend nonetheless reinforced views of male superiority by "dressing like a man" and repeatedly insisting on not being a woman. Scott Larson, disagreeing with narratives that categorize the Public Universal Friend within the gender binary as a woman, suggests that the Friend can be understood as a chapter in trans history "before 'transgender'." Bronski further cites the Friend as a rare instance of an early American publicly identifying as non-binary.

6.3. Social Impact Analysis

T. Fleischmann's essay "Time Is the Thing the Body Moves Through" examines the Friend's narrative through the lens of the colonizing nature of evangelism in the United States, viewing it as "a way to think through the limitations of imagination as a white settler." The Public Universal Friend was also featured in an episode of the NPR radio program and podcast Throughline, further highlighting their enduring relevance in contemporary discussions about identity and history.