1. Early Life and Background

Born Theophylactus in Rome around 1012, Benedict IX was a member of the powerful Tusculum family, a prominent Roman noble lineage with significant influence over the papacy during the 10th and 11th centuries. His father, Alberic III of Tusculum, was a prominent nobleman who exerted considerable political leverage to secure his son's ascension to the highest office in the Church. The family's dominance was evident in their familial connections to several previous popes, underscoring their entrenched power within the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

1.1. Family Connections and Papal Election

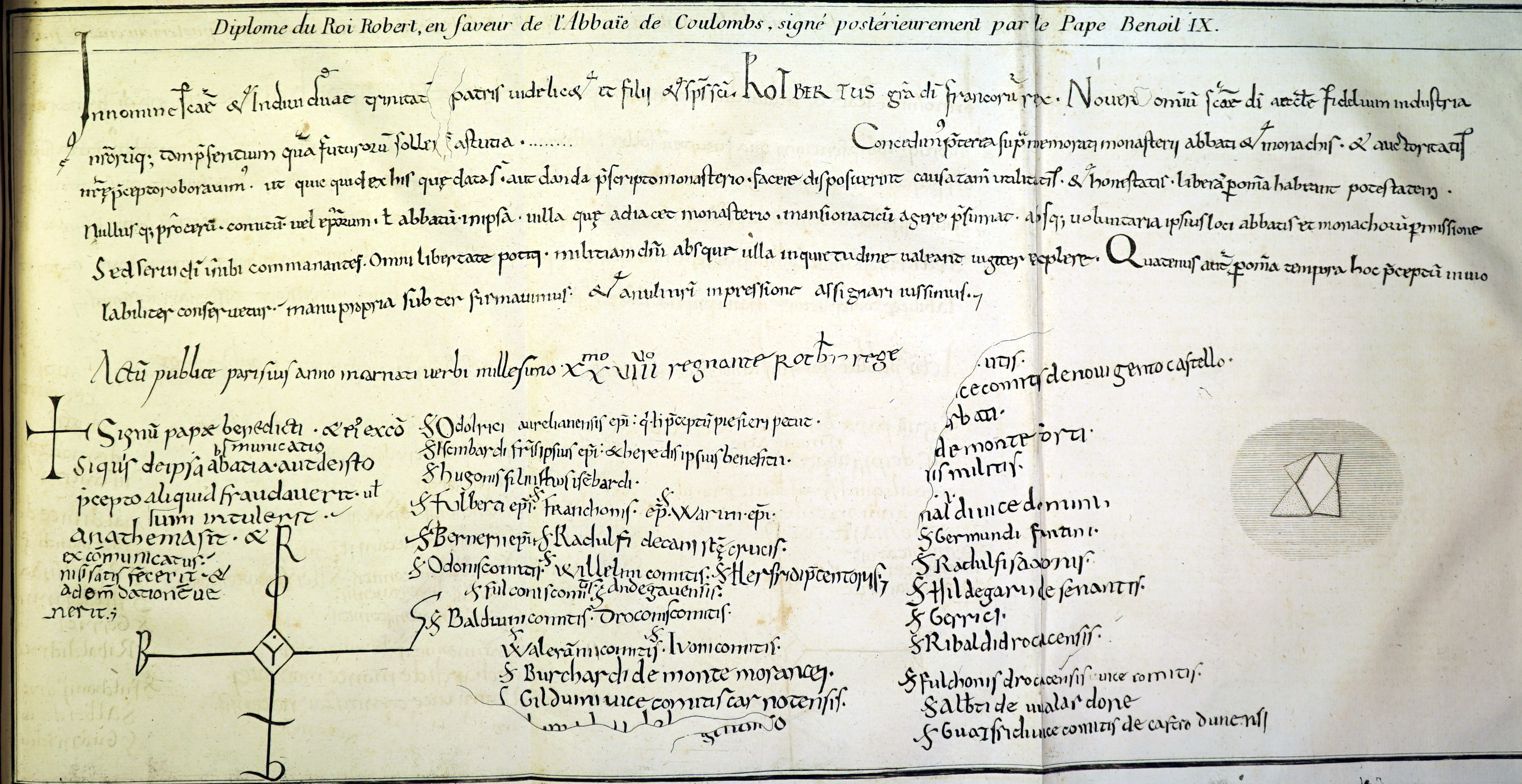

Theophylactus was closely related to multiple popes, being a nephew of both Benedict VIII and John XIX (his immediate predecessor). He was also a grandnephew of John XII, a great-grandnephew of John XI, and a first cousin twice removed of Benedict VII, and potentially a distant relative of Sergius III. In October 1032, Theophylactus's father, Alberic III, successfully obtained the papal chair for him through extensive bribery of the Roman populace and clergy. At the time of his first election, Benedict IX was approximately 20 years old, making him one of the youngest popes in history. However, some sources, including the unsubstantiated testimony of the monk Rupert Glaber, claim he could have been as young as 11 or 12 years old. Despite his profound youth, he was said to have rapidly progressed through all ecclesiastical dignities within a single day before his crowning.

2. First Pontificate (1032-1044)

Benedict IX's initial period as pope, from October 1032 to September 1044, was widely considered scandalous and was plagued by persistent factional strife within Rome. Contemporary chroniclers and later historians levied severe accusations against his conduct. Ferdinand Gregorovius, a prominent anti-papal historian, famously wrote that during Benedict's reign, "It seemed as if a demon from hell, in the disguise of a priest, occupied the chair of Peter and profaned the sacred mysteries of religion by his insolent courses." Horace K. Mann similarly labeled him "a disgrace to the Chair of Peter."

Beyond general misconduct, specific accusations of moral depravity were rampant. Pope Victor III, in his third book of Dialogues, expressed horror at Benedict's actions, stating, "his rapes, murders and other unspeakable acts of violence and sodomy. His life as a pope was so vile, so foul, so execrable, that I shudder to think of it." Bishop Benno of Piacenza also accused Benedict of "many vile adulteries and murders." Saint Peter Damian, in his treatise Liber Gomorrhianus, depicted Benedict IX as one who "feasted on debauchery" and condemned him for routine sodomy, bestiality, and sponsoring orgies within the Lateran Palace. Peter Damian himself initiated reforms and, on his advice, Benedict IX even stripped two bishops of their positions due to simony. Despite these numerous severe criticisms, some historians, like Reginald Lane Poole, suggest that while Benedict was likely "a negligent Pope, very likely a profligate man," the most extreme accusations against his character were made during a period of intense political hostility, especially when his political opponents were in the ascendant. Poole also notes that the full extent of accusations only emerged after he discredited himself by selling the papacy, and that the portrayals worsened over time and distance.

During his first pontificate, Benedict IX was briefly forced out of Rome in 1036 due to opposition to his dissolute lifestyle. However, he managed to return with the support of Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II, who had previously intervened on his behalf by expelling opposing bishops from Piacenza and Cremona. His reign was not entirely uneventful in political affairs; for example, he excommunicated Emperor Conrad II when the emperor unlawfully removed Archbishop Heribert of Milan. He also showed independence by revoking a decision Conrad II had imposed on John XIX regarding the Aquileia patriarchate in 1044. Additionally, Benedict IX canonized Simeon Syracusa, who had died as a hermit in Trier. Nevertheless, in September 1044, renewed opposition to his conduct and the Tusculan family's heavy-handed rule once again forced him out of the city, leading to the election of Sylvester III as his successor by the Crescentius family.

3. Second Pontificate (1045) and Papal Sale

Benedict IX's supporters and forces managed to return to Rome in April 1045, successfully expelling his rival, Sylvester III (whom Benedict IX immediately excommunicated), and allowing Benedict to resume the papacy for a second, albeit brief, term. This period was short-lived as Benedict, reportedly doubting his own ability to maintain his position and desiring to marry his cousin, decided to resign from the papacy in May 1045.

In an unprecedented and highly controversial act, Benedict IX offered to give up the papacy to his godfather, the pious priest John Gratian, on the condition that he would be reimbursed for his election expenses. John Gratian paid a substantial sum for the office, which some accounts estimate to be equivalent to over 1433 lb (650 kg) of gold, and was subsequently recognized as Pope Gregory VI. This transaction is considered one of the most egregious examples of simony in Church history and deeply stained the reputation of the papacy. Peter Damian, while hailing the change with joy, immediately urged the new pope to address the pervasive scandals plaguing the Church in Italy, specifically pointing out the wickedness of bishops in Pesaro, Città di Castello, and Fano.

4. Third Pontificate (1047-1048) and Final Deposition

Benedict IX soon regretted his resignation and, driven by a persistent desire for the papal throne, returned to Rome in November 1047 following the death of Pope Clement II in October of that year. He seized the Lateran Palace and once again declared himself pope, marking his third controversial ascension. However, this third pontificate was short-lived, lasting only until July 1048.

The situation in Rome, with three rival claimants to the papacy (Benedict IX, Sylvester III, and Gregory VI), became untenable, prompting a number of influential clergy and laity to appeal to Holy Roman Emperor Henry III to intervene and restore order. Henry III crossed the Brenner Pass into Italy and convened the Council of Sutri in December 1046 to resolve the chaotic situation. At this council, Benedict IX and Sylvester III were declared deposed. Gregory VI, though considered more legitimate, was encouraged to resign due to the simoniacal nature of his agreement with Benedict IX. Henry III then had a German bishop, Suidger of Bamberg, elected as the new pope, who took the name Clement II.

Benedict IX, who had not attended the Council of Sutri, refused to accept his deposition. Following Clement II's death, his return in November 1047 was met with further imperial intervention. German troops, specifically those sent by Marquis Boniface Canossa at Henry III's command, ultimately drove him from Rome in July 1048, and Damasus II (Poppo of Brixen), another German, was elected to fill the power vacuum and was universally recognized. Benedict IX continued to refuse to appear before charges of simony in 1049 and was subsequently excommunicated, along with his relatives. After Pope Leo IX died in April 1054, Benedict IX even attempted to reclaim the papacy once more, but failed. His repeated attempts to regain the papacy, even after being officially deposed multiple times and excommunicated, highlight his stubbornness and the profound instability of the papacy during this era.

5. Criticisms and Controversies

Benedict IX's papacy is consistently portrayed as one of the most disgraceful periods in Church history, primarily due to his highly controversial conduct and the numerous accusations of moral depravity and corruption leveled against him. His contemporaries and subsequent historians offered scathing assessments:

- Moral Depravity:** Accusations of a profoundly immoral and dissolute lifestyle were rampant. Pope Victor III detailed "rapes, murders, and other unspeakable acts of violence and sodomy," describing Benedict's life as pope as "vile, foul, and execrable." Bishop Benno of Piacenza similarly accused him of "many vile adulteries and murders." Saint Peter Damian's Liber Gomorrhianus specifically implicated Benedict IX in routine sodomy, bestiality, and the sponsorship of orgies within the Lateran Palace. These accounts suggest a severe moral decline at the very top of the Church hierarchy.

- Simony and Corruption:** The most infamous controversy was his sale of the papacy to John Gratian (Pope Gregory VI). This act of simony-the buying or selling of ecclesiastical privileges-was a flagrant abuse of power and undermined the spiritual authority of the papal office. This transaction was widely condemned and contributed significantly to the perception of the papacy as deeply corrupt and worldly. His family's use of bribery to secure his initial election further highlights the pervasive corruption that characterized his ascent.

- Violence and Instability:** Benedict IX's reign was marked by political turmoil and factional strife. His reliance on his family's armed forces, particularly those of the Tusculum counts, to secure and regain the papal throne, and his excommunication of Emperor Conrad II for political reasons, illustrate a papacy deeply entangled in secular power struggles rather than spiritual leadership. The repeated expulsions and returns to Rome underscore the instability he brought to the Holy See.

- Impact on the Papacy:** Critics, such as Ferdinand Gregorovius and Horace K. Mann, viewed Benedict IX as a "demon" or a "disgrace" to the See of Peter. His actions and the ensuing scandals significantly damaged the Church's moral standing and prestige, contributing to widespread calls for reform within the Church. While some historians, like Reginald Lane Poole, suggest that some of the more extreme accusations might have been exaggerated by political opponents seeking to discredit him, the overall consensus remains that his conduct was deeply detrimental to the reputation of the papacy.

6. Later Life and Death

The precise details of Benedict IX's later life after his final deposition in July 1048 remain somewhat obscure, with conflicting accounts regarding his final years. However, it is generally believed that he eventually relinquished his claims to the papal throne.

According to the abbot of the Abbey of Grottaferrata, Saint Bartholomew of Grottaferrata (and Abbot Luca, his fourth successor), Benedict IX spent his last years in penitence, turning away from the sins he had committed as pontiff, and may have become a monk. He is believed to have died around 1056, although some sources suggest his death occurred in 1055 or even as late as 1065 or 1085. He was reportedly buried in the Abbey of Grottaferrata, near Rome. Although claims of his repentance and alleged monastic conversion exist, particularly from monastic sources, the factual basis for these assertions is debated among historians. Furthermore, Pope Leo IX is said to have lifted the excommunication imposed on Benedict IX.

7. Historical Assessment and Legacy

Benedict IX is widely considered one of the most notorious and controversial popes in the history of the Catholic Church. The overwhelming historical assessment of his pontificate is predominantly negative, with his actions often cited as a prime example of the moral decay and corruption that afflicted the papacy in the 11th century.

His tenure is highlighted as a period during which the spiritual authority of the papacy was severely undermined by worldly pursuits, nepotism, and outright simony. The act of selling the papacy, his scandalous personal life, and his multiple, irregular accessions to the papal throne are frequently presented as stark illustrations of the challenges faced by the Church during the "saeculum obscurum" (Dark Age) or the Tusculan Papacy. Many church historians, including Peter Damian, condemned his lifestyle and behavior as utterly incompatible with the dignity of his office.

However, some historians, such as Reginald Lane Poole, offer a more nuanced view, attempting to contextualize his actions within the exceptionally turbulent political landscape of 11th-century Rome. Poole suggests that while Benedict IX was undoubtedly a "negligent Pope" and likely "a profligate man," many of the more extreme accusations against him may have been exaggerated or fabricated by his fierce political adversaries, especially during the period when his opponents were gaining power. Nonetheless, even these attempts at re-evaluation do not negate the profound negative impact he had on the Church. His story serves as a cautionary tale regarding the dangers of political interference in ecclesiastical affairs and the consequences of leadership marked by scandal and corruption, emphasizing the critical need for reform that would eventually come with the Gregorian Reform. His legacy remains that of a pope whose actions significantly damaged the spiritual credibility of the Holy See, making him a perpetual subject of debate and a symbol of papal misrule.