1. Life

Phineas Gage's life, marked by a singular, catastrophic accident, became a subject of intense scientific and public fascination, influencing the understanding of brain function and recovery.

1.1. Background and Early Life

Phineas P. Gage was the first of five children born to Jesse Eaton Gage and Hannah Trussell (Swetland) Gage in Grafton County, New Hampshire. While his exact birthplace remains uncertain, Lebanon, New Hampshire, is often cited as his "native place." Little is known about his upbringing and education beyond the fact that he was literate.

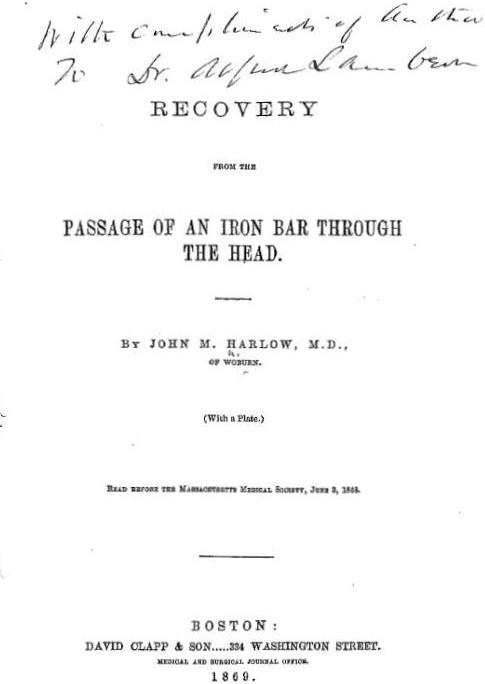

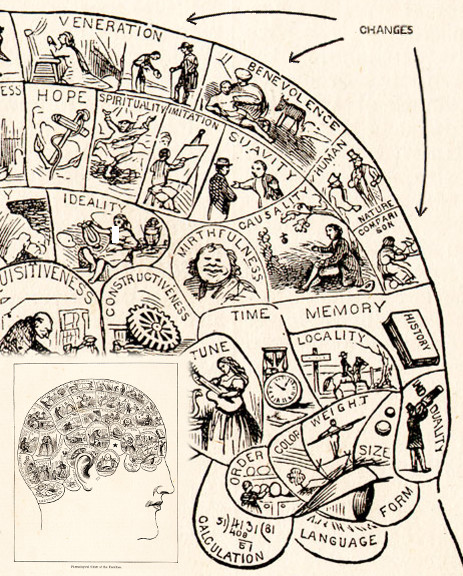

Physician John Martyn Harlow, who knew Gage before his accident, described him as "a perfectly healthy, strong and active young man, twenty-five years of age, nervo-bilious temperament, five feet six inches [2.0 in (5 cm)] in height, average weight one hundred and fifty pounds [331 lb (150 kg)], possessing an iron will as well as an iron frame; muscular system unusually well developed-having had scarcely a day's illness from his childhood to the date of [his] injury." In the context of 19th-century phrenology, "nervo-bilious" indicated an unusual combination of "excitable and active mental powers" with "energy and strength [of] mind and body [making] possible the endurance of great mental and physical labor."

Gage may have gained experience with explosives on farms as a youth or in nearby mines and quarries. By July 1848, he was employed on the construction of the Hudson River Railroad near Cortlandt Town, New York, and by September, he was a blasting foreman, possibly an independent contractor, on railway construction projects. His employers regarded him as "the most efficient and capable foreman in their employ," describing him as "a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation." He had even commissioned a custom-made tamping iron-a large iron rod-for use in setting explosive charges.

1.2. The Accident

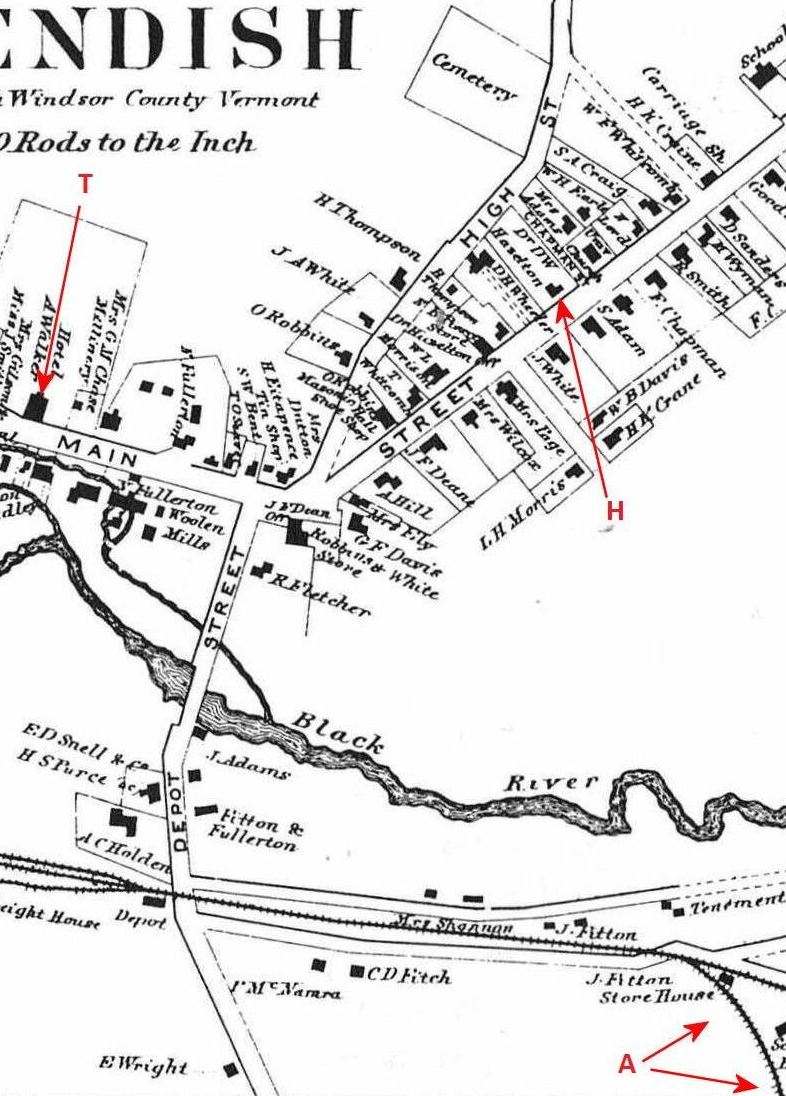

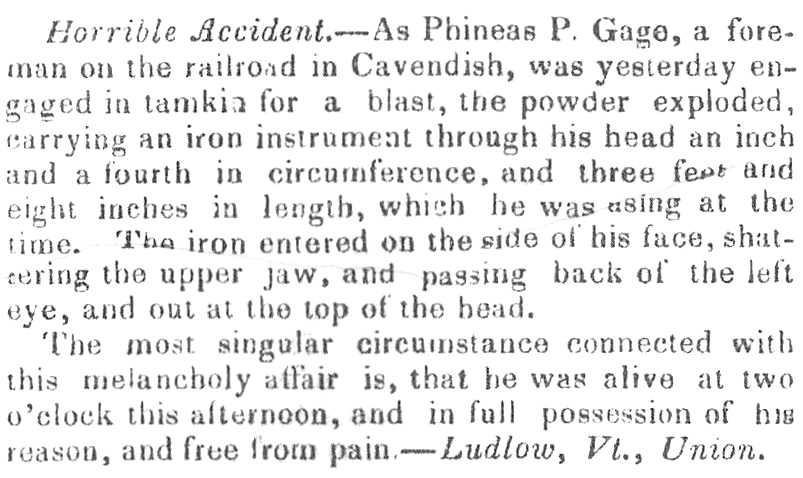

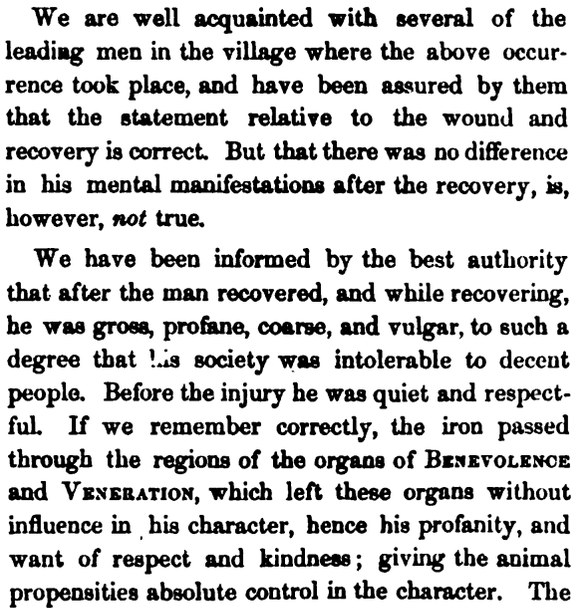

On September 13, 1848, Gage was directing a work gang blasting rock to prepare the roadbed for the Rutland & Burlington Railroad south of the village of Cavendish, Vermont. The process involved boring a hole deep into a rock outcrop, adding blasting powder and a fuse, and then using the tamping iron to pack sand, clay, or other inert material into the hole above the powder to contain the blast's energy and direct it into the surrounding rock. The blast hole was about 0.7 in (1.75 cm) in diameter and up to 39 ft (12 m) deep, potentially requiring three men working a full day to bore with hand tools.

Around 4:30 p.m., as Gage was performing this task, his attention was momentarily diverted by his men working behind him. As he looked over his right shoulder and inadvertently brought his head into line with the blast hole and tamping iron, he opened his mouth to speak. At that exact moment, the tamping iron sparked against the rock, and the powder exploded, possibly because the sand had been omitted.

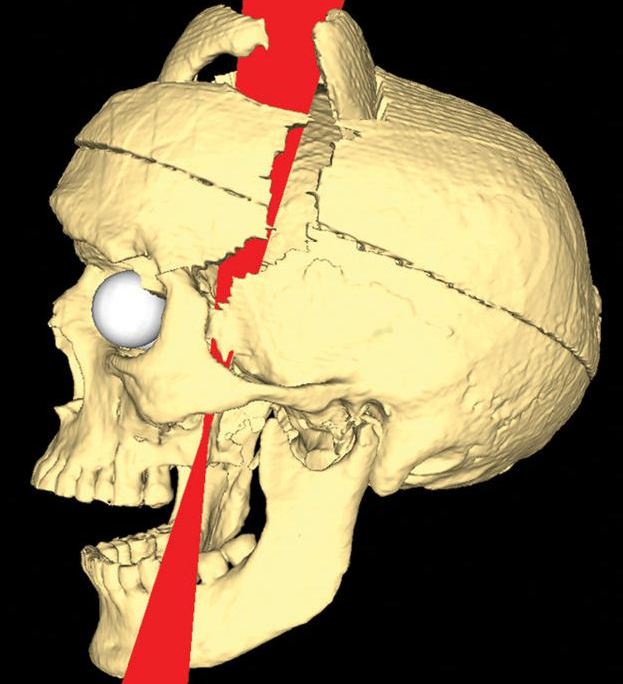

The tamping iron-0.5 in (1.25 cm) in diameter, 9.8 ft (3 m) long, and weighing 29 lb (13.25 kg)-was rocketed from the hole. It entered the left side of Gage's face in an upward direction, just forward of the angle of his lower jaw. Continuing upward outside the upper jaw and possibly fracturing the cheekbone, it passed behind his left eye, through the left side of his brain, and then completely out the top of his skull through the frontal bone. The end that entered his cheek was pointed, tapering for 4.3 in (11 cm) to a 0.1 in (0.25 cm) point, a circumstance to which he may have owed his life.

The tamping iron landed point-first some 262 ft (80 m) away, "smeared with blood and brain." Gage was thrown onto his back and experienced brief convulsions of the arms and legs, but spoke within a few minutes. He walked with little assistance and sat upright in an oxcart for the 0.5 mile (0.75 km) ride to his lodgings in town. A possibly apocryphal newspaper report claimed Gage made an entry in his time-book while en route.

About 30 minutes after the accident, physician Edward H. Williams found Gage sitting in a chair outside the hotel. Gage greeted him with what is considered "one of the great understatements of medical history," saying, "Doctor, here is business enough for you." Williams noted the pulsations of the brain were very distinct, and the top of Gage's head appeared "somewhat like an inverted funnel." Gage persisted in describing how the bar went through his head, and upon vomiting, about half a teacupful of brain matter was expelled onto the floor through the exit hole.

Harlow took charge of the case around 6 p.m., describing the scene as "truly terrific" but noting Gage's "most heroic firmness." Gage recognized Harlow immediately and expressed hope that he was not much hurt, appearing perfectly conscious but exhausted from the hemorrhage. His body and the bed were "literally one gore of blood." Gage was also swallowing blood, which he regurgitated every 15 or 20 minutes.

1.3. Treatment and Convalescence

With Williams' assistance, Harlow shaved the scalp around the exit wound, removed coagulated blood, small bone fragments, and about 0.0 oz (1 g) of protruding brain tissue. After probing for foreign bodies and replacing two large detached pieces of bone, Harlow closed the wound with adhesive straps, leaving it partially open for drainage. The entrance wound in the cheek was bandaged loosely for the same reason. A wet compress was applied, followed by a nightcap and further bandaging to secure the dressings. Harlow also dressed Gage's deeply burned hands and forearms and ordered his head to be kept elevated.

Late that evening, Harlow noted Gage's "Mind clear" and "constant agitation of his legs." Gage stated he "does not care to see his friends, as he shall be at work in a few days."

Despite Gage's optimism, his convalescence was long, difficult, and uneven. He recognized his mother and uncle, who were summoned from Lebanon, New Hampshire, 19 mile (30 km) away, on the morning after the accident. However, on the second day, he "lost control of his mind, and became decidedly delirious." By the fourth day, he was again "rational... knows his friends," and after a week's further improvement, Harlow considered it "possible" for Gage to recover, though this improvement was short-lived.

Beginning 12 days after the accident, Gage was semi-comatose, "seldom speaking unless spoken to, and then answering only in monosyllables." On the 13th day, Harlow noted "Failing strength... coma deepened; the globe of the left eye became more protuberant, with "fungus" (deteriorated, infected tissue) pushing out rapidly from the internal canthus as well as from the wounded brain, and coming out at the top of the head." By the 14th day, "the exhalations from the mouth and head [are] horribly fetid." His friends and attendants expected his death hourly, having his coffin and clothes ready. One attendant even implored Harlow to stop treatment, believing it would only prolong his suffering.

Galvanized, Harlow "cut off the fungi which were sprouting out from the top of the brain and filling the opening, and made free application of caustic [i.e., crystalline silver nitrate]] to them." He laid open the frontalis muscle from the exit wound down to the top of the nose, immediately discharging 0.5 in3 (8 ml) of "ill-conditioned pus, with blood, and excessively fetid." Gage was fortunate to encounter Harlow, whose experience with cerebral abscesses, gained at Jefferson Medical College, likely saved his life. Harlow's decision not to repeat the mistake of his former professor, Joseph Pancoast, who failed to maintain drainage from a similar head injury, was crucial. By keeping the exit wound open and elevating Gage's head to encourage drainage, Harlow prevented a fatal reaccumulation of pus.

On the 24th day, Gage "succeeded in raising himself up, and took one step to his chair." A month later, he was walking "up and down stairs, and about the house, into the piazza." While Harlow was absent for a week, Gage was "in the street every day except Sunday," his desire to return to his family in New Hampshire being "uncontrollable by his friends." He went without an overcoat and with thin boots, got wet feet, and developed a chill and fever, but by mid-November was "feeling better in every respect [and] walking about the house again." Harlow's prognosis at this point was that Gage "appears to be in a way of recovering, if he can be controlled."

By November 25, 10 weeks after his injury, Gage was strong enough to return to his parents' home in Lebanon, New Hampshire, traveling in a "close carriage" (an enclosed conveyance often used for transporting the insane). Although "quite feeble and thin... weak and childish" upon arrival, by late December he was "riding out, improving both mentally and physically." By the following February, he was "able to do a little work about the horses and barn, feeding the cattle etc." and by May or June, he could do "half a day's work." In August 1849, his mother told an inquiring physician that his memory seemed somewhat impaired, though subtly enough that a stranger would not notice.

1.4. Physical Injuries

In April 1849, Gage returned to Cavendish and visited Harlow, who noted at that time the complete loss of vision and ptosis of the left eye. Though the tamping iron's passage had forced the left eye from its orbit by half its diameter, it retained "indistinct" vision until the tenth day after the accident. The vision loss was likely secondary to acute glaucoma or swelling of the optic nerve and compression against the rigid walls of the optic canal, as the optic canal itself was spared. Harlow also observed a large scar on the forehead (from the draining of the abscess) and "upon the top of the head... a quadrangular fragment of bone... raised and quite prominent. Behind this is a deep depression, two inches by one and one-half inches [2.0 in (5 cm) by 1.6 in (4 cm)] wide, beneath which the pulsations of the brain can be perceived. Partial paralysis of the left side of the face." His rearmost left upper molar, adjacent to the point of entry through the cheek, was also lost, presumably during the accident or shortly thereafter.

Despite these injuries, Harlow wrote that "physically, the recovery was quite complete during the four years immediately succeeding the injury," although some weakness remained a year later.

1.5. Later Life and Career

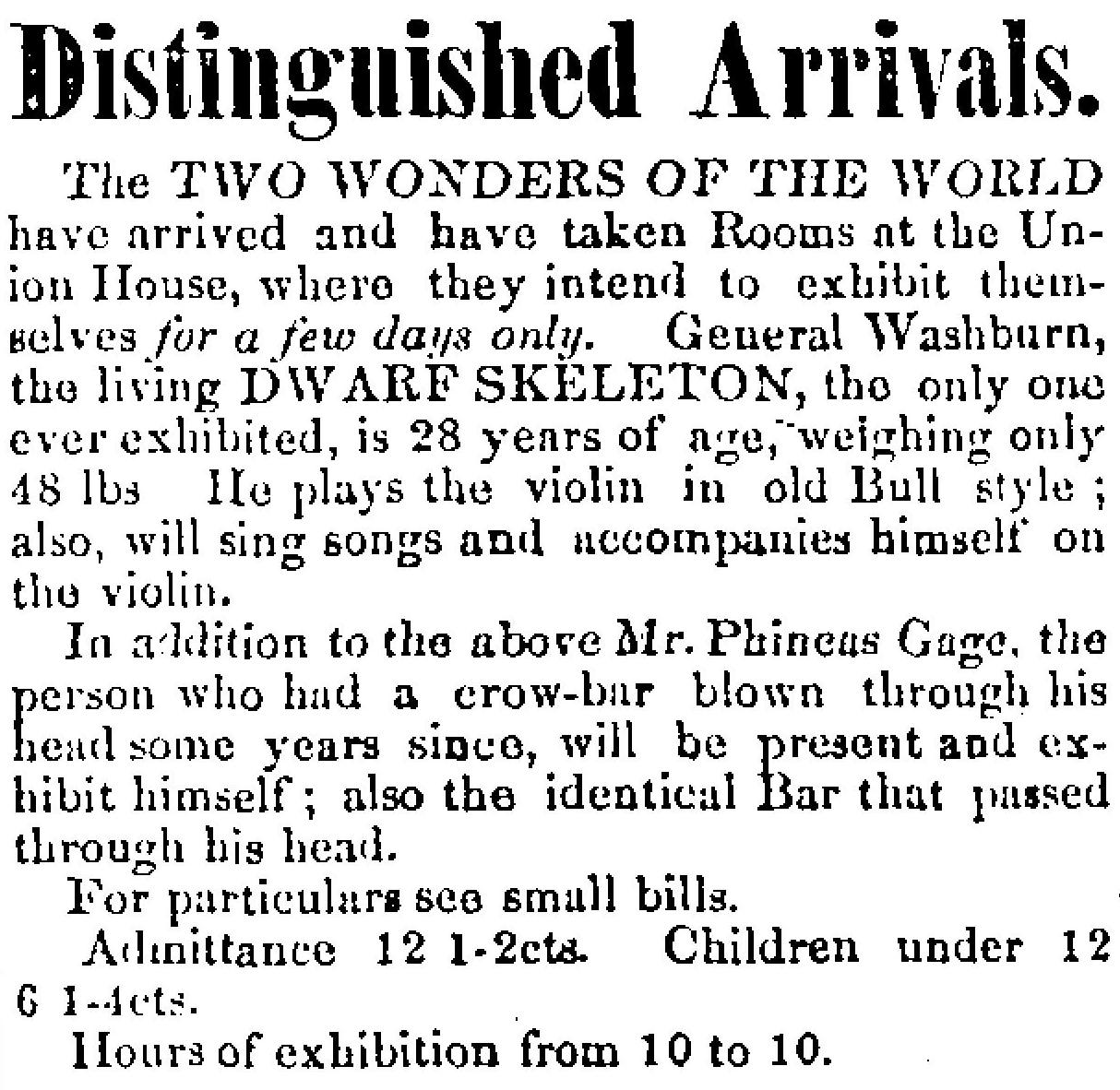

In November 1849, Henry Jacob Bigelow, Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School, brought Gage to Boston for several weeks. After confirming that the tamping iron had indeed passed through Gage's head, Bigelow presented him to the Boston Society for Medical Improvement and possibly to a medical school class. Gage may have been one of the earliest patients to enter a hospital primarily for medical research rather than treatment, and one of the first patients exhibited in an entertainment venue.

Unable to reclaim his railroad job due to the perceived change in his mind, Gage worked for a time as "a kind of living museum exhibit" at Barnum's American Museum in New York City. This was a permanent museum, not a traveling circus, and there is no evidence Gage ever exhibited with a troupe or at a fairground. Advertisements for public appearances by Gage, which he may have arranged and promoted himself, have also been found in New Hampshire and Vermont, supporting Harlow's statement that Gage made public appearances in "most of the larger New England towns." Bigelow later wrote that Gage was "a shrewd and intelligent man and quite disposed to do anything of that sort to turn an honest penny," but gave up such efforts because "that sort of thing has not much interest for the general public." For about 18 months, he worked for the owner of a stable and coach service in Hanover, New Hampshire.

In August 1852, Gage was invited to Chile to work as a long-distance stagecoach driver there. He was responsible for "caring for horses, and often driving a coach heavily laden and drawn by six horses" on the Valparaíso-Santiago route. Harlow noted that Gage was "accustomed to entertain his little nephews and nieces with the most fabulous recitals of his wonderful feats and hair-breadth escapes, without any foundation except in his fancy. He conceived a great fondness for pets and souvenirs, especially for children, horses and dogs-only exceeded by his attachment for his tamping iron, which was his constant companion during the remainder of his life."

After his health began to fail in mid-1859, he left Chile for San Francisco, arriving "in a feeble condition, having failed very much since he left New Hampshire." He had experienced "many ill turns while in Valparaiso, especially during the last year, and suffered much from hardship and exposure." In San Francisco, he recovered under the care of his mother and sister, who had relocated there from New Hampshire around the time he went to Chile. "Anxious to work," he found employment with a farmer in Santa Clara.

In February 1860, Gage began to experience epileptic seizures. He lost his job, and as the seizures increased in frequency and severity, he "continued to work in various places [though he] could not do much."

1.6. Social Recovery Hypothesis

The observation that Gage was able to hold a demanding job as a stagecoach driver in Chile suggests that his most serious mental changes were temporary. This implies that the "fitful, irreverent... capricious and vacillating" Gage described by Harlow immediately after the accident became, over time, far more functional and socially adapted. This conclusion is reinforced by the responsibilities and challenges associated with stagecoach work, which required drivers to "be reliable, resourceful, and possess great endurance. But above all, they had to have the kind of personality that enabled them to get on well with their passengers."

A day's work for Gage meant "a 13 hour journey over 62 mile (100 km) of poor roads, often in times of political instability or frank revolution." All this, in a land whose language and customs Gage arrived as an utter stranger, argues against permanent disinhibition (an inability to plan and self-regulate), as do the extremely complex sensory-motor and cognitive skills required of a coach driver. An American visitor noted that "The departure of the coach was always a great event at Valparaiso-a crowd of ever-astonished Chilenos assembling every day to witness the phenomenon of one man driving six horses."

Psychologist Malcolm Macmillan proposes that this contrast between Gage's early and later post-accident behavior reflects his "gradual change from the commonly portrayed impulsive and uninhibited person into one who made a reasonable 'social recovery'." He cites cases of individuals with similar injuries for whom "someone or something gave enough structure to their lives for them to relearn lost social and personal skills." Gage's survival and rehabilitation demonstrated a theory of recovery that has influenced the treatment of frontal lobe damage today. In modern treatment, adding structure to tasks, such as mentally visualizing a written list, is considered a key method in coping with frontal lobe damage.

Gage's daily routine as a stagecoach driver-rising early, preparing, grooming, feeding, and harnessing horses, being at the departure point at a specified time, loading luggage, charging fares, settling passengers, and caring for them on the journey-provided a highly structured environment. This structure required control of any impulsiveness he may have had. Much foresight was required en route, as drivers had to plan for turns well in advance and react quickly to maneuver around other coaches, wagons, and birlochos traveling at various speeds. Adaptation was also necessary for the physical condition of the route, which included dangerously steep and very rough sections.

This type of highly structured environment, where clear sequences of tasks were required but contingencies demanding foresight and planning arose daily, resembles rehabilitation regimens first developed by Soviet neuropsychologist Alexander Luria for reestablishing self-regulation in World War II soldiers suffering frontal lobe injuries. A neurological basis for such recoveries may be found in emerging evidence that damaged [neural] tracts may re-establish their original connections or build alternative pathways as the brain recovers from injury. Macmillan suggests that if Gage made such a recovery, figuring out how to live despite his injury, it "would add to current evidence that rehabilitation can be effective even in difficult and long-standing cases." He further poses the question: if Gage could achieve such improvement without medical supervision, "what are the limits for those in formal rehabilitation programs?" As author Sam Kean put it, "If even Phineas Gage bounced back-that's a powerful message of hope."

1.7. Death and Exhumation

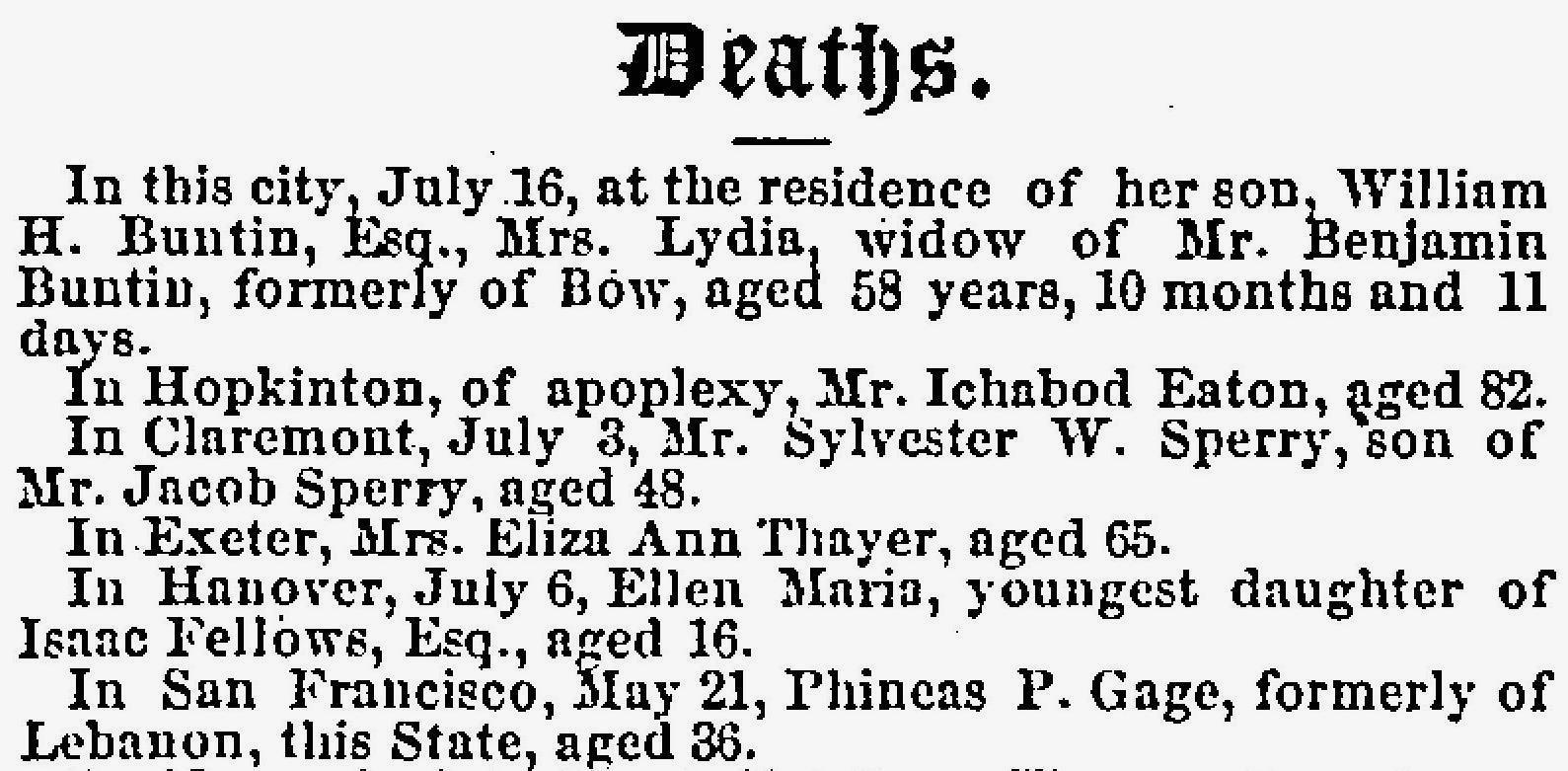

In February 1860, Gage began to have epileptic seizures. He lost his job, and as the seizures increased in frequency and severity, he "continued to work in various places [though he] could not do much." On May 18, 1860, Gage "left Santa Clara and went home to his mother." At 5 a.m. on May 20, he had a severe convulsion. The family physician was called in and bled him. The convulsions were repeated frequently during the succeeding day and night, and he died in status epilepticus late on May 21, 1860, in or near San Francisco. He was buried in San Francisco's Lone Mountain Cemetery.

In 1866, Harlow, who had "lost all trace of [Gage], and had well nigh abandoned all expectation of ever hearing from him again," learned that Gage had died in California and contacted his family there. At Harlow's request, the family had Gage's skull exhumed, then personally delivered it to Harlow, who was by then a prominent physician, businessman, and civic leader in Woburn, Massachusetts.

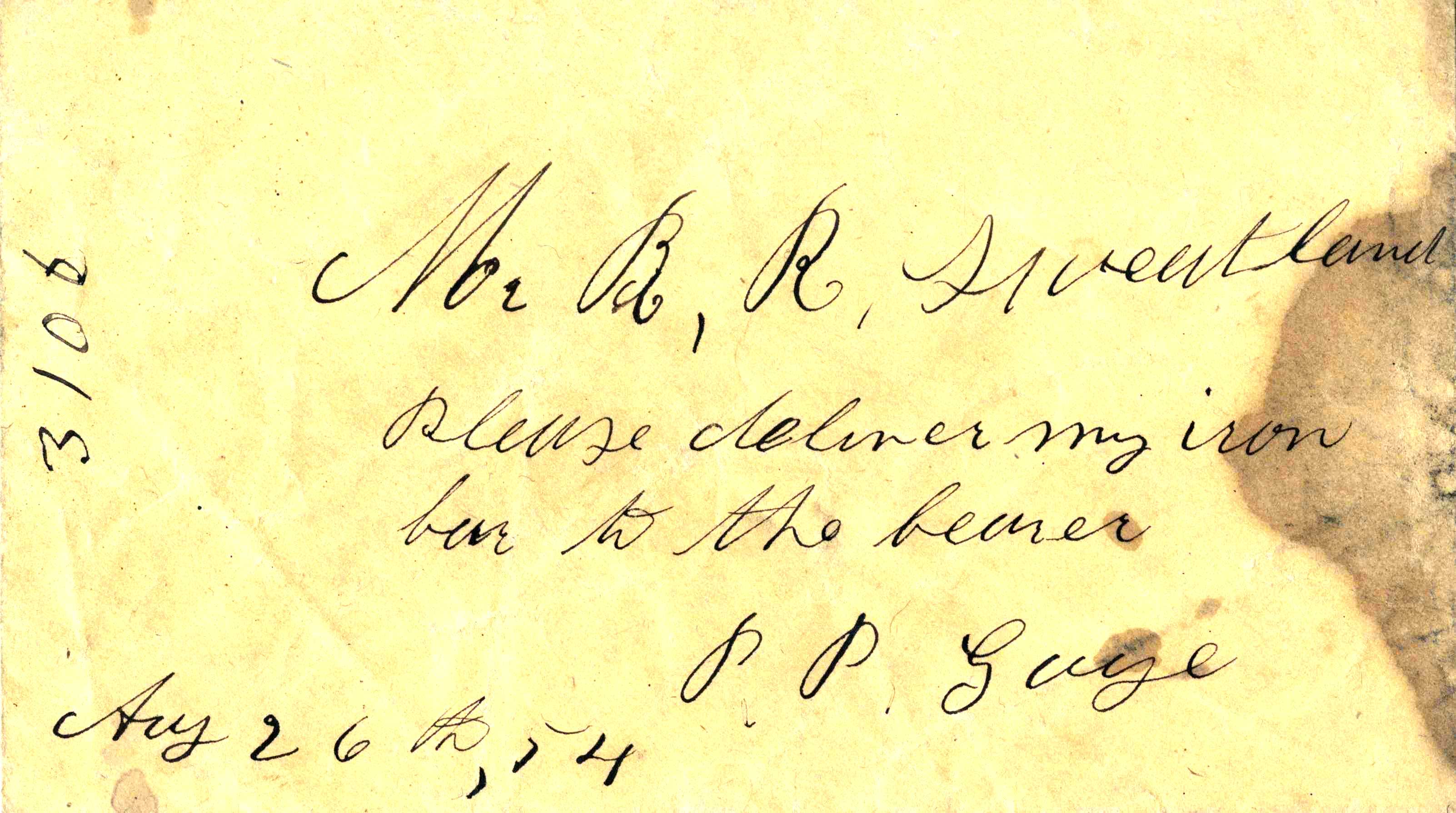

About a year after the accident, Gage had given his tamping iron to Harvard Medical School's Warren Anatomical Museum, but he later reclaimed it and made what he called "my iron bar" his "constant companion during the remainder of his life." Now, it too was delivered by Gage's family to Harlow. (Though some accounts assert that Gage's iron had been buried with him, there is no evidence for this.) After studying them for a triumphant 1868 retrospective paper on Gage, Harlow redeposited the iron-this time with the skull-in the Warren Museum, where they remain on display today.

The tamping iron bears the following inscription, commissioned by Bigelow in conjunction with the iron's original deposit in the Museum (though the date given for the accident is one day off):

This is the bar that was shot through the head of Mr Phinehas[sic] P. Gage at Cavendish Vermont Sept 14,[sic] 1848. He fully recovered from the injury & deposited this bar in the Museum of the Medical College of Harvard University.----Phinehas P. Gage----Lebanon Grafton Cy N-H----Jan 6 1850

The date Jan 6 1850 falls within the period during which Gage was in Boston under Bigelow's observation.

In 1940, Gage's headless remains were moved to Cypress Lawn Memorial Park as part of a mandated relocation of San Francisco's cemeteries to outside city limits.

2. Mental Changes and Brain Damage

Gage's case may have been the first to suggest the brain's role in determining personality and that damage to specific parts of the brain might induce specific personality changes, but the nature, extent, and duration of these changes have been difficult to establish. Only a handful of sources provide direct information on Gage's character (either before or after the accident). The mental changes published after his death were much more dramatic than anything reported while he was alive, and few sources explicitly state the periods of Gage's life to which their various descriptions (which vary widely in their implied level of functional impairment) are meant to apply.

2.1. Pre-accident Personality

Harlow, considered "virtually our only source of information" on Gage by psychologist Malcolm Macmillan, described the pre-accident Gage as hard-working, responsible, and "a great favorite" with the men in his charge. His employers regarded him as "the most efficient and capable foreman in their employ." Harlow also noted that Gage's memory and general intelligence seemed unimpaired after the accident, outside of the delirium exhibited in the first few days.

2.2. Reported Post-accident Personality Changes

Despite Gage's apparent physical recovery, his employers, after the accident, "considered the change in his mind so marked that they could not give him his place again." Harlow's detailed description of Gage's post-accident personality, though not published until 1868 (after Gage's death and his family had supplied his skull), was based on observations made soon after the accident:

The equilibrium or balance, so to speak, between his intellectual faculties and animal propensities, seems to have been destroyed. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operations, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. A child in his intellectual capacity and manifestations, he has the animal passions of a strong man. Previous to his injury, although untrained in the schools, he possessed a well-balanced mind, and was looked upon by those who knew him as a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation. In this regard his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was "no longer Gage."

This description is now routinely quoted. In the interim, Harlow's 1848 report, published just as Gage was emerging from his convalescence, merely hinted at psychological symptoms, stating, "The mental manifestations of the patient, I reserve to a future communication. I think the case... is exceedingly interesting to the enlightened physiologist and intellectual philosopher."

However, after Bigelow termed Gage "quite recovered in faculties of body and mind" with only "inconsiderable disturbance of function," a rejoinder in the American Phrenological Journal stated, "That there was no difference in his mental manifestations after the recovery [is] not true... he was gross, profane, coarse, and vulgar, to such a degree that his society was intolerable to decent people." This account was apparently based on information anonymously supplied by Harlow.

Historians explain Bigelow's and Harlow's contradictory evaluations (less than a year apart) by differences in their educational backgrounds, particularly their attitudes toward cerebral localization (the idea that different regions of the brain are specialized for different functions) and phrenology (the 19th-century pseudoscience that held that talents and personality can be inferred from the shape of a person's skull). Harlow's interest in phrenology prepared him to accept the change in Gage's character as a significant clue to cerebral function, while Bigelow's training predisposed him to minimize such changes, believing that damage to the cerebral hemispheres had no intellectual effect. A reluctance to ascribe a biological basis to "higher mental functions" (functions beyond merely sensory and motor) may have been a further reason Bigelow discounted the behavioral changes Harlow had noted.

2.3. Extent and Duration of Changes

In 1860, an American physician who had known Gage in Chile in 1858 and 1859 described him as still "engaged in stage driving [and] in the enjoyment of good health, with no impairment whatever of his mental faculties." This, combined with the fact that Gage was hired by his employer in advance in New England to become part of the new coaching enterprise in Chile, implies that Gage's most serious mental changes had been temporary. The "fitful, irreverent... capricious and vacillating" Gage described by Harlow immediately after the accident became, over time, far more functional and socially adapted.

Macmillan writes that this conclusion is reinforced by the responsibilities and challenges associated with stagecoach work in Chile, which required drivers to be reliable, resourceful, possess great endurance, and, crucially, have a personality that enabled them to get on well with their passengers. The demanding nature of the work-a 13 hour journey over 62 mile (100 km) of poor roads, often during political instability, in a foreign land with unfamiliar language and customs-militates against the idea of permanent disinhibition. This evidence supports the hypothesis that Gage experienced a gradual "social recovery" from his initial impulsive and uninhibited state.

2.4. Exaggeration and Distortion of Accounts

An anonymous limerick states: "A moral man, Phineas Gage

Tamping powder down holes for his wage

Blew his special-made probe

Through his left frontal lobe

Now he drinks, swears, and flies in a rage."

Macmillan's analysis of scientific and popular accounts of Gage found that they almost always distort and exaggerate his behavioral changes far beyond anything described by anyone who had direct contact with him. He concluded that the known facts are "inconsistent with the common view of Gage as a boastful, brawling, foul-mouthed, dishonest useless drifter, unable to hold down a job, who died penniless in an institution." As historian F. G. Barker put it, "As years passed, the case took on a life of its own, accruing novel additions to Gage's story without any factual basis." Even today, many commentators still rely on hearsay and accept the myth that Gage became a psychopath after the accident. The details of his social cognitive impairment have occasionally been inferred or embellished to suit the enthusiasm of the storyteller, making Gage "a (nearly) blank sheet upon which authors can write stories which illustrate their theories and entertain the public."

For example, Harlow's statement that Gage "continued to work in various places; could not do much, changing often, and always finding something that did not suit him in every place he tried" refers only to Gage's final months, after convulsions had set in. However, it has been misinterpreted as meaning that Gage never held a regular job after his accident, was prone to quit in a capricious fit or be let go due to poor discipline, never returned to a fully independent existence, spent the rest of his life living miserably off charity and traveling as a sideshow freak, or died "in careless dissipation." In fact, after his initial post-recovery months spent traveling and exhibiting, Gage supported himself at just two different jobs from early 1851 until just before his death in 1860.

Other behaviors ascribed to the post-accident Gage that are either unsupported by or in contradiction to the known facts include:

- Mistreatment of wife and children (Gage had neither).

- Inappropriate sexual behavior, promiscuity, or impaired sexuality.

- Lack of forethought, concern for the future, or capacity for embarrassment.

- Parading his self-misery and vainglory in showing his wounds.

- "Gambling" himself into "emotional and reputational... bankruptcy."

- Irresponsibility, untrustworthiness, aggressiveness, violence.

- Vagrancy, begging, drifting, drinking.

- Lying, brawling, bullying.

- Psychopathy, inability to make ethical decisions.

- Loss of all respect for social conventions.

- Acting like an "idiot" or a "lout."

- Living as a "layabout" or a "boorish mess."

- Alienating almost everyone who had ever cared about him.

- Dying "due to a debauch."

None of these behaviors are mentioned by anyone who had met Gage or even his family. As Kotowicz put it, "Harlow does not report a single act that Gage should have been ashamed of." Macmillan emphasizes that Gage's case is "a great story for illustrating the need to go back to original sources," as most authors have been "content to summarize or paraphrase accounts that are already seriously in error." Nonetheless, the telling of Gage's story has increased interest in understanding the enigmatic role that the frontal lobes play in behavior and personality. Some instructors use the Gage case to illustrate the importance of critical thinking.

2.5. Extent of Brain Damage

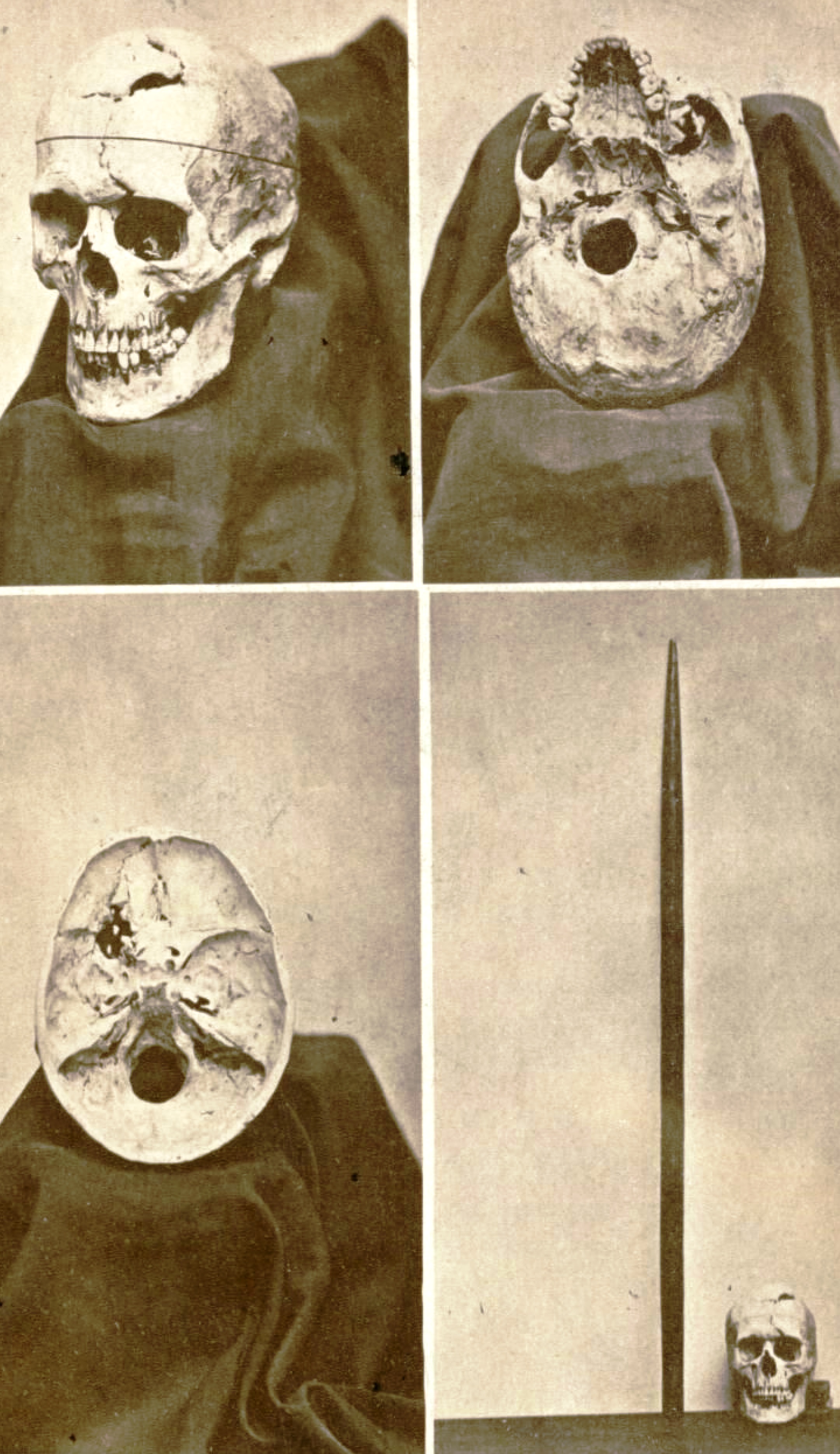

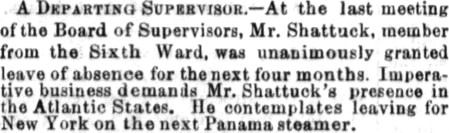

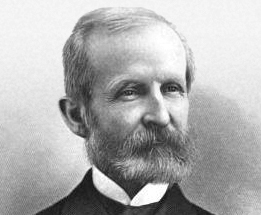

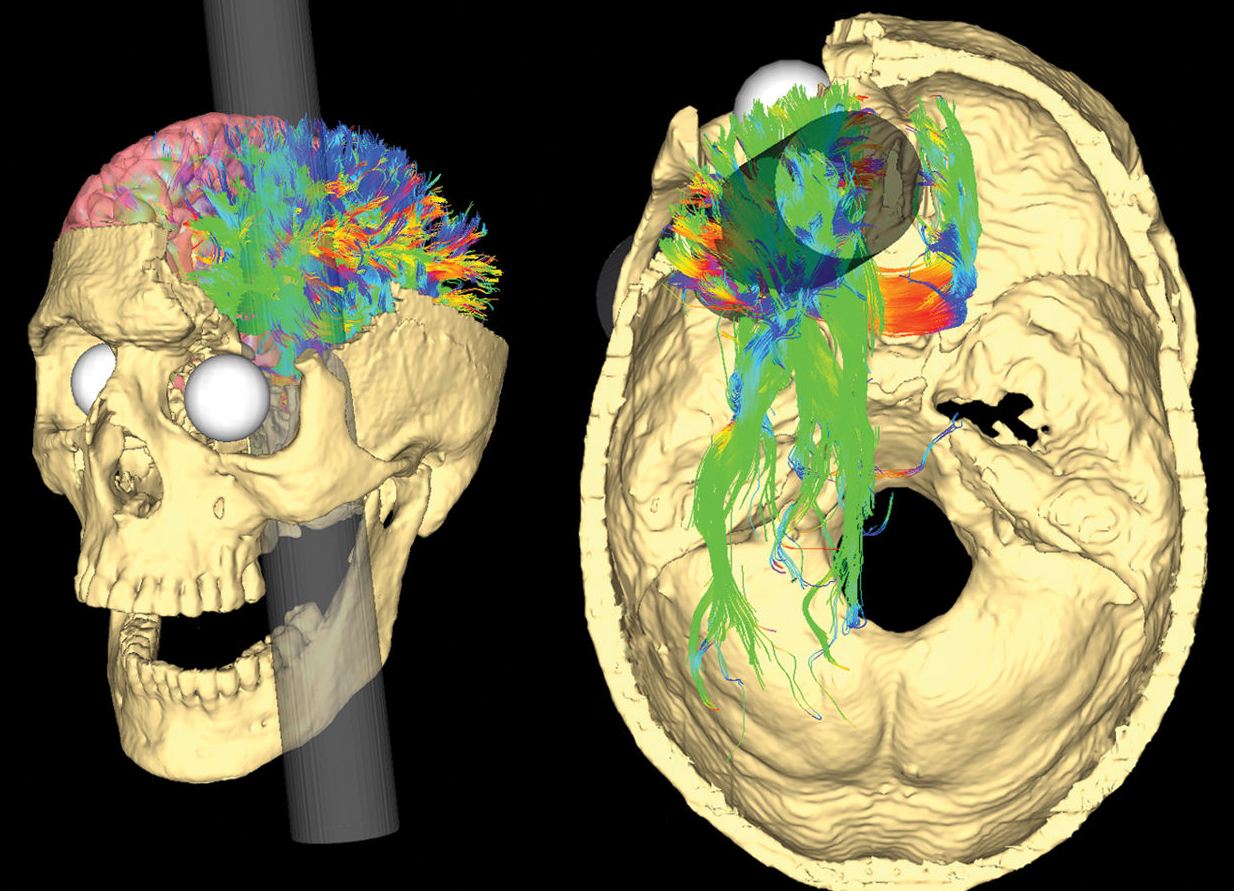

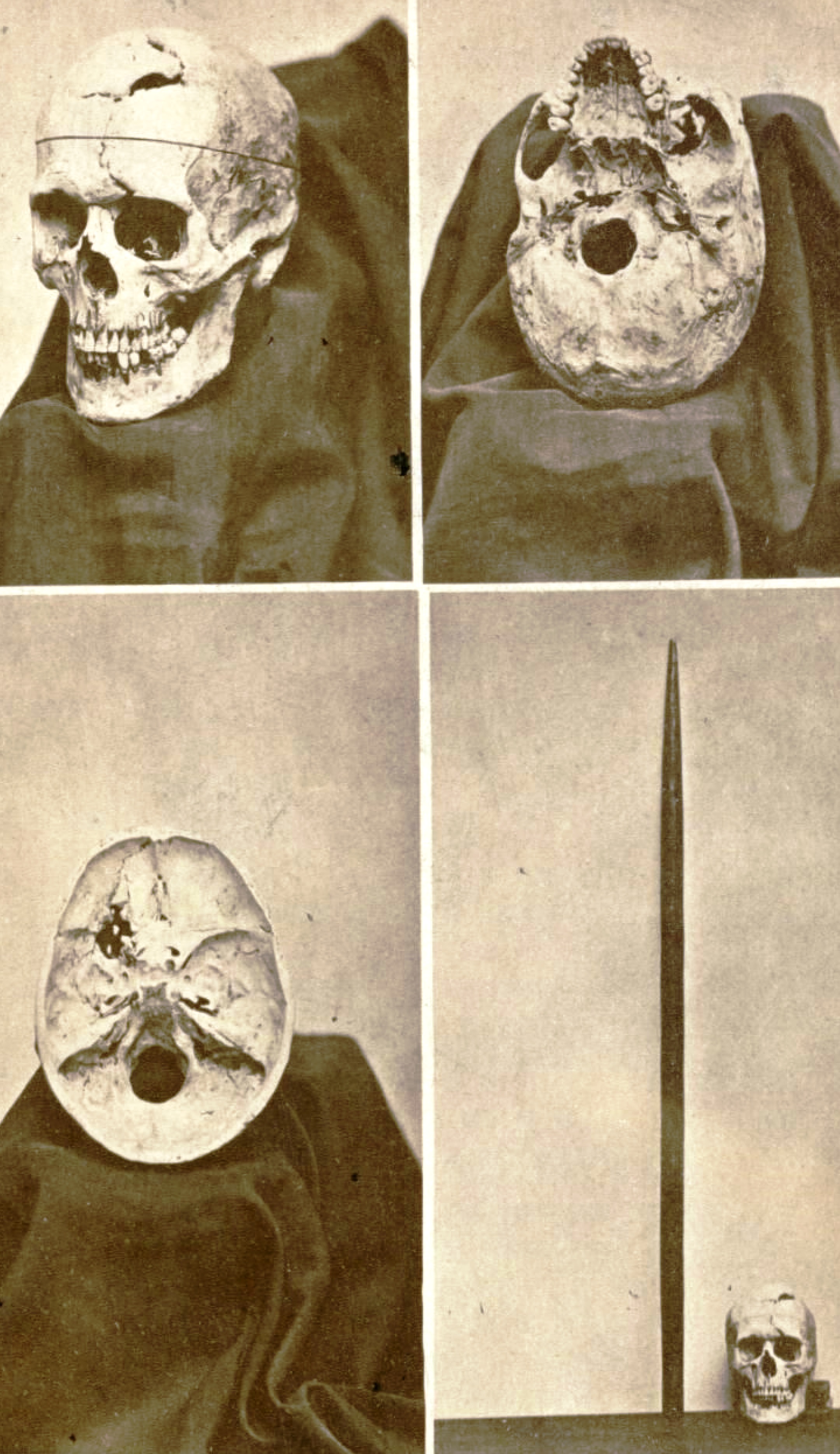

Debate about whether the trauma of Gage's accident, and the subsequent infection, had damaged Gage's left and right frontal lobes, or only the left, began almost immediately after his accident. The 1994 conclusion by Hanna Damasio et al. that the tamping iron did physical damage to both lobes was drawn not from Gage's skull but from a cadaver skull digitally deformed to match the dimensions of Gage's, and made a priori assumptions about the location of Gage's internal injuries and the exit wound which in some cases contradict Harlow's observations.

Using CT scans of Gage's actual skull, Ratiu et al. (2004) and Van Horn et al. (2012) both rejected that conclusion, agreeing with Harlow's belief-based on probing Gage's wounds with his fingers-that only the left frontal lobe had been damaged. Ratiu et al. noted that the hole in the base of the cranium (created as the tamping iron passed through the sphenoidal sinus into the brain) has a diameter about half that of the iron itself. Combining this with the hairline fracture beginning behind the exit region and running down the front of the skull, they concluded that the skull "hinged" open as the iron entered from below, then was pulled closed by the resilience of soft tissues once the iron had exited through the top of the head. This hypothesis also helps explain Gage's survival, as the temporary increase in cranial volume would have allowed the brain to move aside, limiting concussive effects.

Van Horn et al. concluded that damage to Gage's white matter (of which they made detailed estimates) was as or more significant to Gage's mental changes than cerebral cortex (gray matter) damage. They noted extensive damage to the frontal lobes, left temporal polar, and insular cortex, with neural pathways extending beyond the left frontal lobe to the left temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes, as well as the basal ganglia and brainstem. Thiebaut de Schotten et al. (2015) estimated white-matter damage in Gage and two other case studies ("Tan" and "H.M."), concluding that these patients "suggest that social behavior, language, and memory depend on the coordinated activity of different [brain] regions rather than single areas in the frontal or temporal lobes."

Harlow saw Gage's survival as demonstrating "the wonderful resources of the system in enduring the shock and in overcoming the effects of so frightful a lesion, and as a beautiful display of the recuperative powers of nature." He listed several circumstances favoring it:

- The subject was the man for the case: Gage's physique, will, and capacity of endurance were exceptional.

- The shape of the missile: Being pointed, round, and comparatively smooth, it did not leave prolonged concussion or compression. Despite its large diameter and mass, the tamping iron's relatively low velocity drastically reduced the energy available to compressive and concussive "shock waves."

- The point of entrance: The tamping iron did little injury until it reached the floor of the cranium, where it created an opening in the base of the skull for drainage, without which recovery would have been impossible.

- The portion of the brain traversed: For several reasons, this was the best-fitted of any part of the cerebral substance to sustain the injury. This refers to the understanding that injuries to the front of the brain are less dangerous than those to the rear, which frequently interrupt vital functions like breathing and circulation.

Ratiu et al. and Van Horn et al. both concluded that the tamping iron passed left of the superior sagittal sinus and left it intact, both because Harlow does not mention loss of cerebrospinal fluid through the nose, and because otherwise Gage would almost certainly have suffered fatal blood loss or air embolism. Harlow's moderate use of emetics, purgatives, and (in one instance) bleeding would have "produced dehydration with reduction of intracranial pressure [which] may have favorably influenced the outcome of the case."

Harlow modestly stated, "I can only say... with good old Ambroise Paré, I dressed him, God healed him." However, Macmillan calls this self-assessment far too modest, emphasizing Harlow's "skillful and imaginative adaptation [of] conservative and progressive elements from the available therapies to the particular needs posed by Gage's injuries." Harlow, a "relatively inexperienced local physician" at the time, did not apply rigidly what he had learned, for example, forgoing an exhaustive search for bone fragments (which risked hemorrhage and further brain injury) and applying caustic to the "fungi" instead of excising them (which risked hemorrhage) or forcing them into the wound (which risked compressing the brain).

3. Scientific and Cultural Significance

Gage's case is considered the "index case for personality change due to frontal lobe damage." However, the uncertain extent of his brain damage and the limited understanding of his behavioral changes render him "of more historical than neurologic interest." Macmillan writes that "Phineas' story is [primarily] worth remembering because it illustrates how easily a small stock of facts becomes transformed into popular and scientific myth," the paucity of evidence having allowed "the fitting of almost any theory [desired] to the small number of facts we have." A similar concern was expressed as early as 1877, when British neurologist David Ferrier complained that "In investigating reports on diseases and injuries of the brain, I am constantly being amazed at the inexactitude and distortion to which they are subject by men who have some pet theory to support. The facts suffer so frightfully..."

More recently, neurologist Oliver Sacks refers to the "interpretations and misinterpretations [of Gage] from 1848 to the present." Some scholars discuss the use of Gage to promote "the myth, found in hundreds of psychology and neuroscience textbooks, plays, films, poems, and YouTube skits[:] Personality is located in the frontal lobes... and once those are damaged, a person is changed forever."

3.1. Role in Cerebral Localization Debate

In the 19th-century debate over whether various mental functions are localized in specific regions of the brain, both sides managed to enlist Gage in support of their theories. For example, after Eugene Dupuy wrote that Gage proved that the brain is not localized (characterizing him as a "striking case of destruction of the so-called speech centre without consequent aphasia"), Ferrier replied by using Gage (along with the woodcuts of his skull and tamping iron from Harlow's 1868 paper) to support his thesis that the brain is localized.

3.2. Influence of Phrenology

Throughout the 19th century, adherents of phrenology contended that Gage's mental changes (his profanity, for example) stemmed from destruction of his mental "organ of Benevolence"-the part of the brain responsible for "goodness, benevolence, the gentle character... [and] to dispose man to conduct himself in a manner conformed to the maintenance of social order"-and/or the adjacent "organ of Veneration"-related to religion and God, and respect for peers and those in authority. Phrenology held that the organs of the "grosser and more animal passions are near the base of the brain; literally the lowest and nearest the animal man [while] highest and farthest from the sensual are the moral and religions feelings, as if to be nearest heaven." Thus, Veneration and Benevolence are at the apex of the skull-the region of exit of Gage's tamping iron.

Harlow wrote that Gage, during his convalescence, did not "estimate size or money accurately[,] would not take 1.00 K USD for a few pebbles" and was not particular about prices when visiting a local store. By these examples, Harlow may have been implying damage to phrenology's "Organ of Comparison," though this is somewhat contradicted by Harlow's statement that Gage paid "with his habitual accuracy" during the store visit.

3.3. Theoretical Misuse and Later Interpretations

Rhodri Hayward states: "The Gage who appears in contemporary psychology textbooks is simply a compound creature-... a stunning example of the ideological uses of case histories and their mythological reconstruction."

It is frequently asserted that what happened to Gage played a role in the later development of various forms of psychosurgery-particularly lobotomy-or even that Gage's accident constituted "the first lobotomy." Aside from the question of why the unpleasant changes usually (if hyperbolically) attributed to Gage would inspire surgical imitation, there is no such direct link, according to Macmillan: "There is simply no evidence that any of these operations were deliberately designed to produce the kinds of changes in Gage that were caused by his accident, nor that knowledge of Gage's fate formed part of the rationale for them... [W]hat his case did show came solely from his surviving his accident: major operations [such as for tumors] could be performed on the brain without the outcome necessarily being fatal."

Antonio Damasio, in support of his somatic marker hypothesis (relating decision-making to emotions and their biological underpinnings), draws parallels between behaviors he ascribes to Gage and those of modern patients with damage to the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala. But Damasio's depiction of Gage has been severely criticized, for example by Kotowicz: "Damasio is the principal perpetrator of the myth of Gage the psychopath... Damasio changes [Harlow's] narrative, omits facts, and adds freely... His account of Gage's last months [is] a grotesque fabrication [insinuating] that Gage was some riff-raff who in his final days headed for California to drink and brawl himself to death... It seems that the growing commitment to the frontal lobe doctrine of emotions brought Gage to the limelight and shapes how he is described." As Kihlstrom put it, "many modern commentators exaggerate the extent of Gage's personality change, perhaps engaging in a kind of retrospective reconstruction based on what we now know, or think we do, about the role of the frontal cortex in self-regulation."

3.4. Gage as a Standard for Brain Injury Cases

As the reality of Gage's accident and survival gained credence, it became "the standard against which other injuries to the brain were judged," and it has retained that status despite competition from a growing list of other unlikely-sounding brain-injury accidents, including encounters with axes, bolts, low bridges, exploding firearms, a revolver shot to the nose, further tamping irons, and falling Eucalyptus branches.

For example, after a miner survived traversal of his skull by a gas pipe 0.2 in (0.625 cm) in diameter (extracted "not without considerable difficulty and force, owing to a bend in the portion of the rod in his skull"), his physician invoked Gage as the "only case comparable with this, in the amount of brain injury, that I have seen reported." Often these comparisons carried hints of humor, competitiveness, or both. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, for example, alluded to Gage's astonishing survival by referring to him as "the patient whose cerebral organism had been comparatively so little disturbed by its abrupt and intrusive visitor." A Kentucky doctor, reporting a patient's survival of a gunshot through the nose, bragged, "If you Yankees can send a tamping bar through a fellow's brain and not kill him, I guess there are not many can shoot a bullet between a man's mouth and his brains, stopping just short of the medulla oblongata, and not touch either."

Similarly, when a lumbermill foreman returned to work soon after a saw cut 1.2 in (3 cm) into his skull from just between the eyes to behind the top of his head, his surgeon (who had removed from this wound "thirty-two pieces of bone, together with considerable sawdust") termed the case "second to none reported, save the famous tamping-iron case of Dr. Harlow," though apologizing that "I cannot well gratify the desire of my professional brethren to possess [the patient's] skull, until he has no further use for it himself."

As these and other remarkable brain-injury survivals accumulated, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal pretended to wonder whether the brain has any function at all: "Since the antics of iron bars, gas pipes, and the like skepticism is discomfitted, and dares not utter itself. Brains do not seem to be of much account now-a-days." The Transactions of the Vermont Medical Society was similarly facetious: "'The times have been,' says Macbeth Act III, 'that when the brains were out the man would die. But now they rise again.' Quite possibly we shall soon hear that some German professor is exsecting it."

4. Remains and Portraits

The physical artifacts associated with Phineas Gage-his skull, tamping iron, and portraits-are invaluable as historical and scientific evidence, offering tangible links to his extraordinary case.

4.1. Portraits

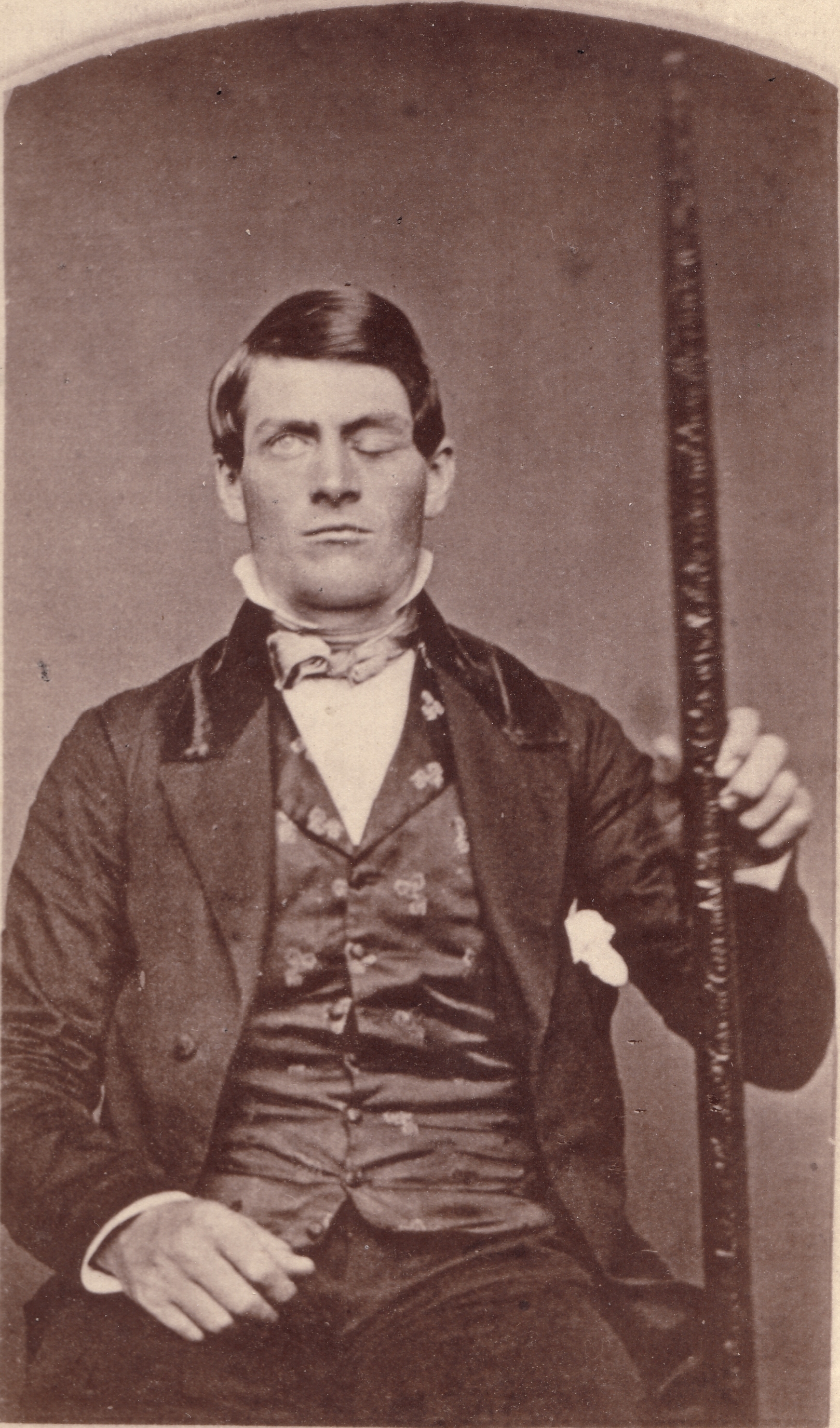

![Inscription on iron as seen in portrait detail: ... [Phine]has P. Gage at Cavendish, Vermont, Sept. 14, 1848. He fully-...](https://cdn.onul.works/wiki/source/19501a410f3_4b41a243.jpg)

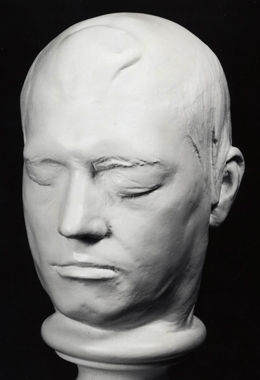

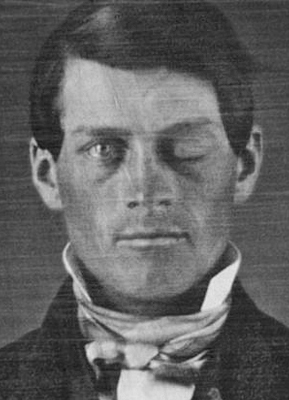

Two daguerreotype portraits of Gage, identified in 2009 and 2010, are the only likenesses of him known other than a plaster head cast taken for Bigelow in late 1849 (and now in the Warren Museum along with Gage's skull and tamping iron). The head cast, taken from life, is often mistakenly referred to as a death mask.

The first portrait shows a "disfigured yet still-handsome" Gage with his left eye closed and scars clearly visible. He appears "well dressed and confident, even proud," holding his iron, on which portions of its inscription can be made out. For decades, the portrait's owners had believed that it depicted an injured whaler with his harpoon. The second portrait, copies of which are in the possession of two branches of the Gage family, shows Gage in a somewhat different pose, wearing the same waistcoat and possibly the same jacket, but with a different shirt and tie.

The authenticity of the portraits was confirmed by overlaying the inscription on the tamping iron, as seen in the portraits, against that on the actual tamping iron, and by matching the subject's injuries to those preserved in the head cast. However, the exact time, place, and photographer of these portraits are unknown, except that they were created no earlier than January 1850 (when the inscription was added to the tamping iron), on different occasions, and are likely by different photographers.

The portraits support other evidence that Gage's most serious mental changes were temporary and that he experienced a social recovery. "That [Gage] was any form of vagrant following his injury is belied by these remarkable images," wrote Van Horn et al. As Sam Kean commented regarding the first image discovered, "Although just one picture, it exploded the common image of Gage as a dirty, disheveled misfit. This Phineas was proud, well-dressed, and disarmingly handsome."

4.2. Skull and Tamping Iron

In 1866, Harlow learned of Gage's death in California and contacted his family. At Harlow's request, the family had Gage's skull exhumed and personally delivered it to him in New England. About a year after the accident, Gage had initially given his tamping iron to Harvard Medical School's Warren Anatomical Museum, but he later reclaimed it, making what he called "my iron bar" his "constant companion during the remainder of his life." Now, it too was delivered by Gage's family to Harlow. (Although some accounts assert that Gage's iron had been buried with him, there is no evidence for this.)

After studying the skull and iron for his triumphant 1868 retrospective paper on Gage, Harlow redeposited the iron-this time with the skull-in the Warren Museum, where they remain on display today. The tamping iron bears an inscription commissioned by Henry Jacob Bigelow, noting the accident date (September 14, 1848, one day off from the actual date) and Gage's full recovery and donation of the bar to the museum. The date "Jan 6 1850" on the inscription falls within the period Gage was under Bigelow's observation in Boston.

In 1940, Gage's headless remains were moved to Cypress Lawn Memorial Park as part of a mandated relocation of San Francisco's cemeteries to outside city limits.

5. Legacy and Commemoration

Phineas Gage's extraordinary case has left a lasting impact on both scientific inquiry and popular culture, serving as a powerful symbol in discussions about the brain and behavior.

5.1. Cultural Impact

Gage's enduring presence in popular culture is significant, extending to books, films, music, and educational materials. He is frequently mentioned in introductory psychology and neuroscience textbooks, serving as a dramatic illustration of the link between brain damage and personality change. His story has been adapted into various forms, including music groups named after him or variations of his name. Despite the widespread distortions of his story, Gage remains a compelling figure, shaping public understanding of brain injury and its potential effects. His case is often used to emphasize the importance of critical thinking and returning to original sources in scientific and historical inquiry.

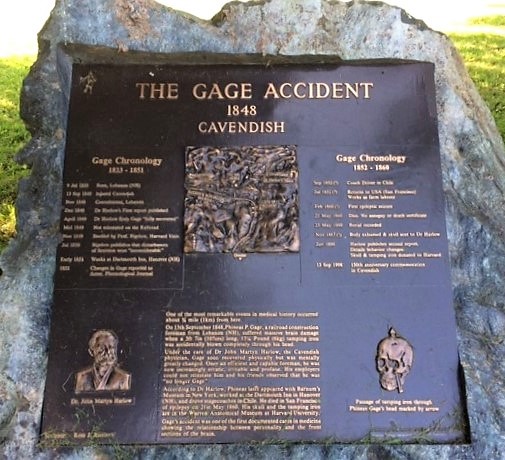

5.2. Memorials

A roadside memorial dedicated to Phineas Gage exists in Cavendish, Vermont, near the site of his accident. This plaque commemorates his remarkable survival and the enduring scientific interest in his case.

6. See also

- Anatoli Bugorski - Scientist whose head was struck by a particle-accelerator proton beam

- Aphasia

- Cognitive neuropsychology

- Cognitive rehabilitation therapy

- Executive functions

- Henry Molaison - Patient "H.M.", who developed severe anterograde amnesia after surgery for epilepsy

- Lev Zasetsky - Soldier who developed agnosia after a bullet pierced his parieto-occipital area

- Neuroplasticity

- Neurorehabilitation

- Occupational therapy

- Penetrating head injury

- Rehabilitation (neuropsychology)

7. External links

- [https://www.nejm.org/action/showMediaPlayer?doi=10.1056%2FNEJMicm031024&aid=NEJMicm031024_attach_1&area= Video reconstruction of tamping iron passing through Gage's skull] (Ratiu et al.)

- [https://www.uakron.edu/gage/ Phineas Gage information page] by the Center for the History of Psychology at the University of Akron

- [https://collections.countway.harvard.edu/onview/exhibits/show/beyond-the-bone-box/the-case-of-phineas-gage Case of Phineas Gage] at the Center for the History of Medicine

- [https://countway.harvard.edu/center-history-medicine/collections/notable-holdings Skull, life cast, and tamping iron of Phineas Gage] at the Warren Anatomical Museum of the Harvard Medical School

- [https://3dprint.nih.gov/discover/3dpx-003118 Skull of Phineas Gage] at the National Institutes of Health 3D print exchange