1. Life

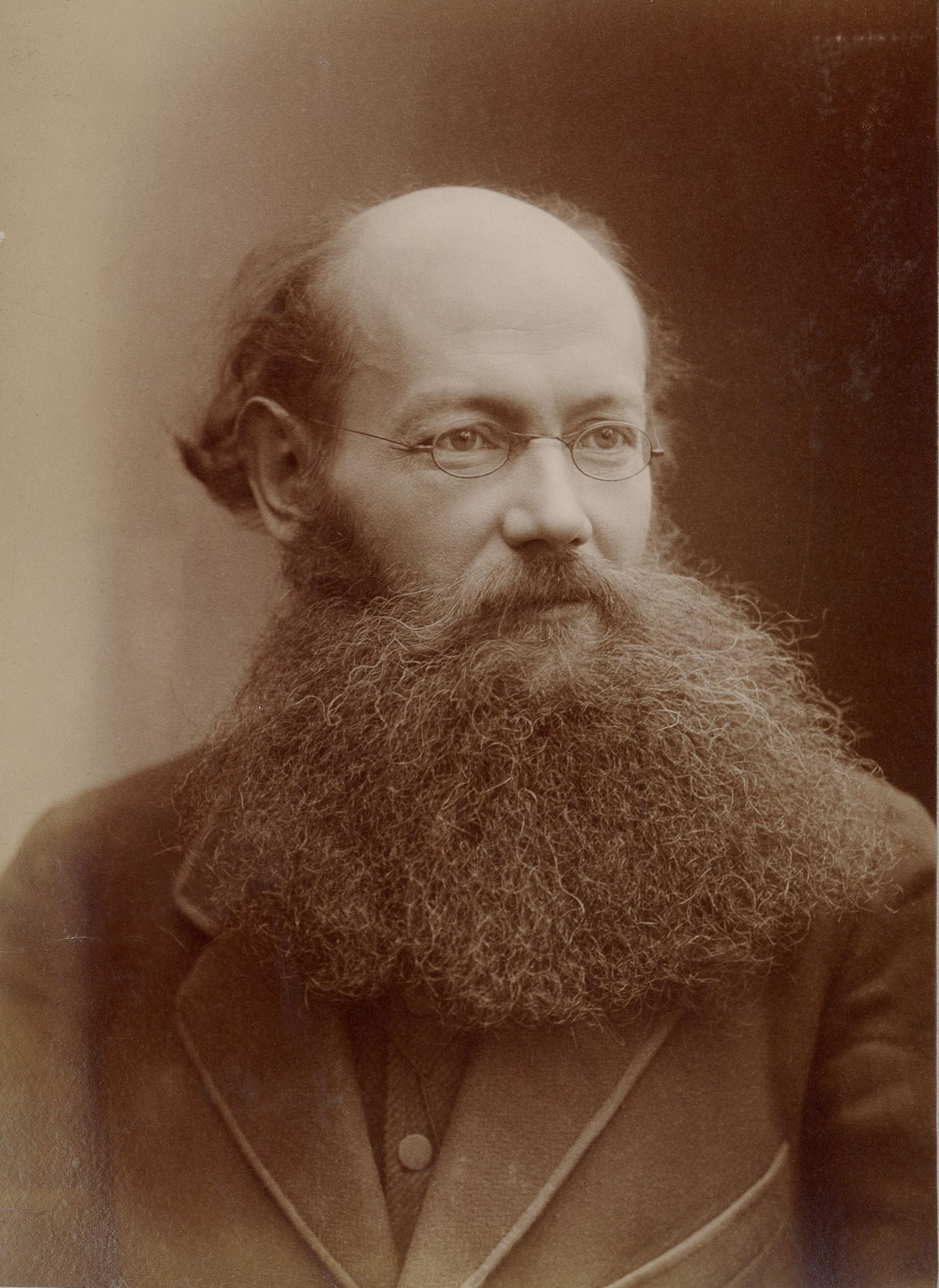

Kropotkin's life was marked by a transformative journey from a privileged aristocratic upbringing to a committed revolutionary, scientist, and philosopher, characterized by periods of intense study, activism, imprisonment, and exile.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was born on December 9, 1842, in the Старая КонюшеннаяStaraya KonyushennayaRussian (Old Equerries) district of Moscow, Russian Empire. He was the third son of Prince Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, a military officer and a descendant of the legendary Rurik dynasty and the princes of Smolensk. His family was a wealthy land-owning noble family, possessing nearly 1,200 serfs across three different provinces: Kaluga Oblast, Ryazan Oblast, and Tambov Oblast. Kropotkin's father, Alexei Petrovich, was described as crude and materialistic, often displaying harshness towards his children and servants. His mother, Ekaterina Nikolaevna Sulima, was the daughter of General Nikolai Sulima and descended from a Zaporozhian Cossack leader. She was known for her intellect and kindness, a stark contrast to her husband. Kropotkin was only three years old when his mother died of tuberculosis. His father remarried two years later, but his stepmother was indifferent and even vindictive towards the Kropotkin children, attempting to erase the memory of their mother. Peter and his older brother, Alexander, were largely raised by their German nurse and the estate's servants and serfs, for whom Kropotkin developed a deep and enduring compassion.

At the age of seven, Kropotkin attended a masquerade ball where he caught the eye of Tsar Nicholas I, who promised him entry into the elite Page Corps in St. Petersburg. This prestigious institution combined military and court education, training future imperial attendants. Although he had to spend two years at Moscow First Middle School due to a lack of vacancies, he eventually joined the Page Corps as a teenager. Despite initially starting in the lowest class due to poor math scores, he quickly excelled, becoming a sergeant-major in 1861 and serving as the emperor's personal Page de Chambre. His views on the Tsar and court life soured as imperial policies changed, and he became preoccupied with the need to live a societally useful life. During his time at the Page Corps, Kropotkin began his first underground revolutionary writings, advocating for a Russian Constitution. He developed a strong interest in science, reading, and opera. At the age of 12, influenced by republican teachings, he renounced his prince title and would later scold friends who referred to him as such. He welcomed Tsar Alexander II's emancipation of serfs in 1861, though he remained skeptical of the Tsar's liberal reputation.

1.2. Siberian Service and Geographical Expeditions

In 1862, for his tour of military service, Kropotkin chose to join the newly formed Amur Cossacks in East Siberia. This was an undesirable post, but it offered him the opportunity to study the technical mathematics of artillery, travel, live in nature, and achieve financial independence from his father. His time in Siberia deepened his compassion for the poor and allowed him to observe the pride and dignity of peasant farmers, contrasting sharply with the indignities of serfdom. He worked as an aide-de-camp to the governor of Transbaikalia in Chita, and later as an attaché for Cossack affairs to the governor-general of East Siberia in Irkutsk. During this period, he wrote approvingly of the cultivated Transbaikalia governor-general Boleslav Kukel, who engaged Kropotkin in prison reform and city self-governance projects. However, these reform efforts were ultimately denied by the central government, leading to Kropotkin's growing disillusionment with administrative reform as an effective means to improve social conditions.

In 1866, Kropotkin began reading political thinkers such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, John Stuart Mill, and Alexander Herzen, which further fueled his revolutionary inclinations. After Kukel's ouster in early 1863, Kropotkin found solace and purpose in geographical work. In 1864, he led a disguised reconnaissance expedition to find a direct route through Manchuria from Chita to Vladivostok. The following year, he explored the East Siberian Mountains in the north. His 1866 Olekminsk-Vitimsk expedition produced mountain measurements that confirmed his hypothesis: the Siberian area from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific Ocean was a plateau and not a plain. This significant discovery of the Patom Plateau and Vitim Plateaus earned him a gold medal from the Russian Geographical Society and contributed to the commercialization of the Lena gold fields. A mountain range in this region was later named in his honor.

Kropotkin also reported on Siberia for St. Petersburg newspapers, covering events such as the condition of Polish political exiles who participated in the unsuccessful 1866 Baikal Insurrection. He secured a promise from the governor-general to suspend the prisoners' death sentences, a promise that was tragically reneged upon. This experience, coupled with the realization that true administrative reform was ineffectual, convinced Kropotkin and his brother to leave the military. His five years in Siberia taught him to appreciate peasant social organization and prepared him for his future as an anarchist.

In 1867, Kropotkin and his brother moved to St. Petersburg, where Kropotkin continued his schooling and academic work, studying physics, mathematics, and geography at Saint Petersburg Imperial University. He took a position with the Russian interior ministry, though with no significant duties. After presenting his Vitim expedition findings, he accepted a part-time offer as Secretary of the Physical Geography section of the Russian Geographical Society. He also translated Herbert Spencer's work for additional income. He continued to develop his theory that the East Siberian mountains were part of a large plateau, considering it his best scientific contribution. In 1870, Kropotkin participated in a polar expedition plan that postulated the existence of what was later discovered as the Franz Josef Land Arctic archipelago. In early 1871, he was commissioned to study the Ice Age in Scandinavian geography, where he developed theories of the glaciation of Europe and the glacial lakes of its northeast. Later that year, his father died, and Kropotkin inherited a wealthy estate in Tambov. Despite being offered the prestigious position of general secretary of the Geographical Society, he declined, choosing instead to focus on his Ice Age data and his growing interest in bettering the lives of peasants.

1.3. Transition to Anarchism

While Kropotkin became increasingly revolutionary in his writings, he was not initially known for his activism. His revolutionary fervor was spurred by the 1871 Paris Commune and the trial of Sergey Nechayev. He and his brother attended meetings discussing the Franco-Prussian War and revolutionary ideas. In February 1872, driven by a desire to witness the socialist workers' movement firsthand, Kropotkin traveled to Switzerland and Western Europe. Over three months, he met Mikhail Sazhin in Zurich and engaged with Nikolai Utin's Marxist group in Geneva, though he eventually fell out with them. He was then introduced to James Guillaume and Adhémar Schwitzguébel of the Jura Federation, the primary internal opposition to the Marxist-controlled First International and followers of Mikhail Bakunin. Kropotkin was immediately impressed and converted to anarchism by the group's egalitarianism and independence of expression. He narrowly missed meeting Bakunin during this visit. After also visiting the movement in Belgium, he returned to Russia in May with contraband revolutionary literature.

Back in St. Petersburg, Kropotkin joined the Chaikovsky Circle, a group of revolutionaries he regarded as more educational than overtly revolutionary. He believed in the inevitability of social revolution and the necessity of stateless social organization. His populist revolutionary program for the group focused on urban workers and peasants, in contrast to the group's moderates who concentrated on students. Partially for this reason, he declined to contribute his personal wealth to the group, viewing professionals as unlikely to forgo their privileges and judging them as not living societally useful lives. His program emphasized federated agrarian communes and a revolutionary party. Although a powerful speaker, Kropotkin was not a successful organizer.

In November 1873, Kropotkin penned his first political memo, outlining his basic plan for stateless social reconstruction. This plan included common property, worker control of factories, shared physical labor towards societal needs, and labor vouchers in lieu of money. He stressed the importance of living among commoners and using propaganda to channel mass dissatisfaction, while rejecting the conspiratorial model of Nechayev. Members of the Chaikovsky Circle began to be arrested in late 1873, and the Third Section secret police apprehended Kropotkin in March 1874. His arrest, as a former Page de Chambre and officer, caused a scandal. At the time, Kropotkin had just submitted his Ice Age report and had recently been elected president of the Geographical Society's Physical and Mathematical Department. At the society's request, the Tsar granted Kropotkin books to complete his glaciation report while he was held in the Peter and Paul Fortress. His brother, Alexander, who had also become radicalized as a follower of Peter Lavrov, was arrested and exiled to Siberia, where he committed suicide about a decade later.

Due to poor health, Kropotkin was moved to the House of Detention prison military hospital in St. Petersburg, with the help of his sister. With assistance from friends, he dramatically escaped from the minimal-security prison in June 1876. After his escape, Kropotkin and his friends celebrated with a celebratory dinner at one of St. Petersburg's finest restaurants, assuming the police would not look for them there. Traveling via Scandinavia and England, Kropotkin arrived in Switzerland by the end of the year, where he met Italian anarchists Carlo Cafiero and Errico Malatesta. He also visited Belgium and Zurich, where he met the French geographer Élisée Reclus, who would become a close friend and collaborator.

1.4. Exile and Activism

Upon his return to Switzerland, Kropotkin became closely associated with the Jura Federation and began editing its publication. In October 1878, he married Sofia Ananyeva-Rabinovich, a Ukrainian Jewish student who was over a decade his junior. Kropotkin often sought her criticism and feedback on his work. Sofia's published story, "The Wife of Number 4,237," was based on her own experiences during her husband's imprisonment at Clairvaux. She later established an archive in Moscow dedicated to his works before her death in 1941.

In 1879, Kropotkin launched Le Révolté (The Rebel), a revolutionary fortnightly newspaper in Geneva. Through this publication, he articulated his personal vision of anarchist communism, emphasizing the idea of distributing work products communally based on need rather than individual labor. Although he did not originate the philosophy, he became its most prominent proponent, and anarcho-communism became part of the Jura Federation's program in 1880 due to his advocacy. Le Révolté also published Kropotkin's widely known pamphlet, "An Appeal to the Young", in 1880.

In early 1881, following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, Switzerland expelled Kropotkin at Russia's insistence. He moved to Thonon-les-Bains, France, near Geneva, so his wife could complete her Swiss education. Upon learning of a plot by the Holy League, a tsarist group, to assassinate him for his alleged connection to the assassination, he moved to London, but found it difficult to settle there and returned to Thonon-les-Bains in late 1882. Shortly after his return, the French authorities arrested him for agitation, partly to appease Russia. He was sentenced to five years in Lyon. In early 1883, he was transferred to Clairvaux Prison, where he continued his academic work. A public campaign involving intellectuals and French legislators called for his release. During his imprisonment, Reclus published Words of a Rebel, a compilation of Kropotkin's Révolté writings, which became a primary source for Kropotkin's thoughts on revolution. As Kropotkin's health deteriorated from scurvy and malaria, France released him in early 1886. He would remain in England until 1917, settling in Harrow, London, though he made brief trips to other European countries. He also lived in Ealing, Bromley, and spent several years in Brighton. In London, Kropotkin befriended many English socialists, including William Morris and George Bernard Shaw.

In late 1886, Kropotkin co-founded Freedom, an anarchist monthly and the first English anarchist periodical, which he continued to support for almost three decades. His only child, Alexandra Kropotkin, was born the following year in London. Over the next few years, he published several influential books, including In Russian and French Prisons and The Conquest of Bread. His intellectual circle in London included figures like William Morris, W. B. Yeats, and old Russian friends Sergey Stepnyak-Kravchinsky and Nikolai Tchaikovsky. Kropotkin also contributed articles to the Geographical Journal and Nature.

After 1890, Kropotkin became more of a scholarly recluse and less of a propagandist, according to biographers George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumović. His revolutionary zeal subsided as he increasingly turned to social, ethical, and scientific questions. He joined the British Association for the Advancement of Science and continued to contribute to Freedom, though he was no longer an editor. Several of Kropotkin's books originated as journal articles. His writings on anarchist communist social life were printed in the French successor to Le Révolté and later revised into The Conquest of Bread in 1892. Kropotkin's ideas on decentralizing production and industry, countering the trend of centralized industrialization, were compiled into his book Fields, Factories, and Workshops in 1899. His research throughout the 1890s on the animal instinct for cooperation, presented as a counterpoint to Darwinism, became a series of articles in Nineteenth Century and, later, the widely translated book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution in 1902.

Following a scientific congress in Toronto in 1897, Kropotkin toured Canada. His experiences there led him to advise the Russian Doukhobors who sought to immigrate to Canada, and he helped facilitate their emigration in 1899. He also visited the United States, meeting prominent figures like John Most, Emma Goldman, and Benjamin Tucker. American publishers released his Memoirs of a Revolutionist and Fields, Factories, and Workshops by the end of the decade. He visited the United States again in 1901 at the invitation of the Lowell Institute to deliver lectures on Russian literature, which were later published. He published The Great French Revolution (1909), The Terror in Russia (1909), and Modern Science and Anarchism (1913). His 70th birthday in 1912 was celebrated with gatherings in London and Paris.

Kropotkin's support for the Western entry into World War I, siding with Britain and France, caused a significant division within the anarchist movement, which was largely anti-war. This stance damaged his esteem as a luminary of socialism, and he further exacerbated the situation by insisting, upon his return to Russia, that Russians should also support the war effort.

1.5. Return to Russia and Later Years

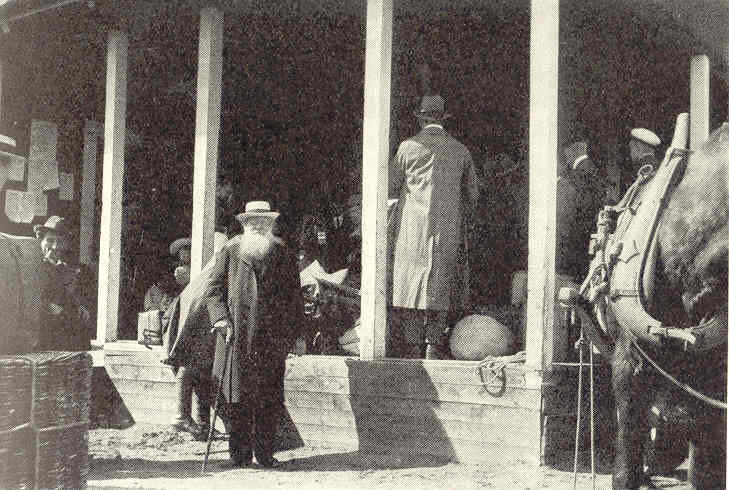

With the outbreak of the Russian Revolution, Kropotkin returned to Russia in June 1917, ending decades of exile. He was greeted by tens of thousands of people. He refused the Petrograd Provisional Government's offer of a cabinet seat as Minister of Education, believing that working with them would violate his anarchist principles. In August, he advocated for defending Russia and the revolution at the National State Conference. In 1918, he applied for residence in Moscow, which was personally approved by Vladimir Lenin, the head of the Soviet government. However, Kropotkin's initial enthusiasm for the revolution turned to profound disappointment when the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution and established a dictatorial regime. He lamented, "this action buried the revolution," arguing that the Bolsheviks had demonstrated how a revolution should *not* be made-through authoritarian rather than libertarian methods.

Finding life in Moscow difficult in his old age, Kropotkin moved with his family to a friend's home in the nearby town of Dmitrov months later. In 1919, Emma Goldman, a close friend and comrade, visited his family there. Kropotkin met Lenin in Moscow and corresponded by mail to discuss political questions of the day. He advocated for workers' cooperatives and strongly argued against the Bolsheviks' hostage policy and centralization of authority, while simultaneously encouraging Western comrades to halt their governments' military interventions in Russia. In a letter to Lenin on March 4, 1920, he wrote, "If the present situation continues, the word 'socialism' will become a curse. This is what happened to the concept of 'equality' in France after forty years of Jacobin rule." Following an announcement of executions later that year, Kropotkin sent Lenin another furious letter, admonishing the terror which Kropotkin saw as needlessly destructive.

Kropotkin ultimately had little direct impact on the Russian Revolution's trajectory, but his advocacy work for political and anarchist prisoners in Russia, and his anti-interventionist stance regarding the Russian Revolution during the last four years of his life, helped to replenish some of the goodwill he had lost due to his support for the Western powers in World War I.

Kropotkin died of pneumonia on February 8, 1921, in Dmitrov. He had been working on his unfinished book, Revolutionary Ethics, in his final years. His family refused an offer of a state funeral from the Bolshevik government. His funeral in Moscow was the last major anarchist demonstration of that period in Russia, attracting a large crowd, the biggest since the October Revolution. Anarchists in the procession carried flags with anti-Bolshevik slogans. Emma Goldman and Aaron Baron delivered eulogies. The Russian anarchist movement, along with Kropotkin's writings, was fully suppressed later that year, and the Soviet Union's dictatorial system continued for over 60 years. Kropotkin's body was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

2. Philosophy

2.1. Critique of Capitalism and State Socialism

Kropotkin launched a scathing critique against what he identified as the fundamental flaws of both feudalism and capitalism. He believed that these economic systems inherently generate poverty and artificial scarcity, while simultaneously promoting social privilege for a select few. As an alternative, he proposed a more decentralized economic system rooted in mutual aid and voluntary cooperation, arguing that the natural tendencies for such organization already exist within both biological evolution and human society.

Kropotkin partially disagreed with the Marxist critique of capitalism, particularly the labor theory of value, believing there was no necessary link between work performed and the values of commodities. His primary attack on the institution of wage labor stemmed from the power employers exerted over employees, a power he contended was made possible by the state's protection of private ownership of productive resources. Kropotkin asserted that the very possibility of surplus value was problematic, holding that a society would remain unjust if the workers of a particular industry retained their surplus for themselves rather than redistributing it for the common good.

Kropotkin firmly believed that a communist society could only be established through a social revolution, which he defined as "the taking possession by the people of all social wealth. It is the abolition of all the forces which have so long hampered the development of Humanity." However, he vehemently criticized revolutionary methods, such as those proposed by Marxism and Blanquism, that sought to retain or utilize state power. He argued that any central authority was fundamentally incompatible with the radical changes required by a social revolution. Kropotkin contended that the mechanisms of the state were deeply entrenched in maintaining the power of one class over another, and thus could not be used to emancipate the working class. Instead, Kropotkin insisted that both private property and the state must be abolished simultaneously.

He articulated that any post-revolutionary government would inherently lack the local knowledge necessary to effectively organize a diverse population. Such a government's vision would be constrained by its own vindictive, self-serving, or narrow ideals. To maintain order, preserve authority, and organize production, the state would inevitably resort to violence and coercion to suppress further revolution and control workers. This reliance on state bureaucracy would prevent workers from developing the initiative to self-organize, leading to the re-creation of classes, an oppressed workforce, and ultimately, another revolution. Kropotkin thus concluded that maintaining the state would paralyze any true social revolution, rendering the idea of a "revolutionary government" a contradiction in terms. He famously stated, "We know that Revolution and Government are incompatible; one must destroy the other, no matter what name is given to government, whether dictator, royalty, or parliament."

Instead of a centralized approach, Kropotkin emphasized the critical need for decentralized organization. He believed that dissolving the state would effectively cripple counter-revolution without resorting to authoritarian methods of control. He argued that this was achievable only through "Boldness of thought, a distinct and wide conception of all that is desired, constructive force arising from the people in proportion as the negation of authority dawns; and finally-the initiative of all in the work of reconstruction-this will give to the revolution the Power required to conquer."

Kropotkin applied this trenchant criticism directly to the Bolsheviks' rule following the October Revolution. In a 1919 letter to the workers of Western Europe, he promoted the possibility of revolution but also issued a stark warning against the centralized control in Russia, which he believed had condemned their revolution to failure. He wrote to Vladimir Lenin in 1920, describing the desperate conditions he attributed to bureaucratic organization and urging Lenin to allow for local and decentralized institutions. Following an announcement of executions later that year, Kropotkin sent Lenin another furious letter, admonishing the terror which he saw as needlessly destructive.

2.2. Theory of Mutual Aid

In 1902, Kropotkin published his seminal work, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. This book presented an alternative view of animal and human survival, directly challenging the prevailing theories of "Social Darwinism" championed by figures like Francis Galton and Thomas Henry Huxley, which emphasized interpersonal competition and natural hierarchy. Kropotkin argued that "it was an evolutionary emphasis on cooperation instead of competition in the Darwinian sense that made for the success of species, including the human."

Drawing from extensive scientific observations of both animal and human societies, Kropotkin contended that cooperation is a fundamental mechanism for survival and evolution. He used numerous real-world examples to demonstrate that cooperation, rather than central control or authoritarian enforcement, is the primary factor promoting progress and survival within groups. He did not deny the existence of competitive urges in humans, but he did not consider them the sole or primary driving force of human history. He believed that seeking out conflict proved to be socially beneficial only in attempts to destroy injustice and authoritarian institutions such as the state or the Russian Orthodox Church, which he viewed as stifling human creativity and impeding the natural human instinct towards cooperation.

In the final chapter of Mutual Aid, Kropotkin summarized his thesis: "In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense - not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species [...] in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits [...] and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development [...] are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay."

Kropotkin asserted that the benefits derived from mutual organization provide a greater incentive for humans than mutual strife. He hoped that, in the long run, mutual organization would drive individuals to produce. Anarcho-primitivists and anarcho-communists often draw upon Kropotkin's ideas, particularly his observations of hunter-gatherer societies, to support the concept of a gift economy as a means to break the cycle of poverty.

2.3. Anarcho-communism

In his 1892 book, The Conquest of Bread, Kropotkin proposed an economic system based on mutual exchanges within a framework of voluntary cooperation. He envisioned a society, sufficiently developed socially, culturally, and industrially to produce all necessary goods and services, where no obstacles like preferential distribution, pricing, or monetary exchange would prevent individuals from taking what they needed from the collective social product. He advocated for the eventual abolition of money or any tokens of exchange for goods and services.

Kropotkin believed that Mikhail Bakunin's collectivist economic model was merely a "wage system by a different name," arguing that such a system would inevitably foster the same kind of centralization and inequality found in a capitalist wage system. He stated that it is impossible to accurately determine the value of an individual's contributions to the products of labor, and anyone attempting to make such determinations would inherently wield authority over those whose wages they controlled.

According to Kirkpatrick Sale, with Mutual Aid and later with Fields, Factories, and Workshops, Kropotkin successfully moved beyond the "absurdist limitations of individual anarchism" and "no-laws anarchism" that had been prevalent during his time. Instead, he offered a vision of "communal anarchism," drawing on the models of independent cooperative communities he observed while developing his theory of mutual aid. This form of anarchism, while opposing centralized government and state-level laws like traditional anarchism, understood that at a certain small scale, communities, communes, and cooperatives could flourish, providing humans with a rich material life and extensive liberties without centralized control.

2.4. Self-Sufficiency and Decentralization

Kropotkin's emphasis on local production informed his view that a country should strive for self-sufficiency by manufacturing its own goods and growing its own food, thereby reducing its reliance on imports. To achieve these ends, he advocated for practical measures such as irrigation and the use of greenhouses to boost local food production. His vision of a decentralized society was one organized through free communes and federations, which he saw as essential for enhancing individual liberty and overall social well-being. He argued for a decentralized, anti-authoritarian revolution, believing that a truly free society must be built from the ground up through local initiatives and voluntary associations.

3. Personal Life

3.1. Marriage and Family

Kropotkin married Sofia Ananyeva-Rabinovich, a Ukrainian Jewish student, in Switzerland in October 1878. Sofia was more than a decade younger than Kropotkin and served as a primary source of criticism and feedback for his work. Her published story, "The Wife of Number 4,237," was based on her own experiences during her husband's imprisonment at Clairvaux. She later established an archive in Moscow dedicated to his works before her death in 1941. Their only child, Alexandra Kropotkin, was born in London in 1887. Kropotkin was generally reserved about his private life.

3.2. Character and Morality

Kropotkin was widely known for possessing exceptional integrity and moral character that perfectly aligned with his beliefs. Even Henry Hyndman, an ideological adversary, recalled Kropotkin's charm and sincerity. These traits, noted by his friend Sergey Stepnyak-Kravchinsky, significantly contributed to Kropotkin's power as a public speaker. Rudolf Rocker observed that Kropotkin was a "whole man" in whom "there was no cleavage between the man and his world. He spoke and acted in all things as he felt and believed and wrote." As a thinker, Kropotkin focused more acutely on issues of morality than on economics or politics, and he lived strictly by his own principles without imposing them on others. In practice, this made him more of a "revolutionary humanitarian" than a revolutionist solely by deed. He was also renowned for his exceptional kindness and for consciously forgoing material comforts to live a revolutionary, principled life by example. Gerald Runkle observed that "Kropotkin with his scholarly and saintly ways ... almost brought respectability to the movement."

His personal philosophy was encapsulated in his famous quotes: "To fight ceaselessly among the people for truth, justice, and equality... one could hardly wish for a nobler life," from his pamphlet "An Appeal to the Young," and "Hope, not despair, makes revolutions succeed," from his autobiography "Memoirs of a Revolutionist." The French writer Romain Rolland remarked that Kropotkin was the only person who truly lived the life advocated by Leo Tolstoy. Oscar Wilde also famously stated that Kropotkin was one of only two truly happy people he had ever known.

4. Legacy and Influence

4.1. Intellectual Legacy

As the leading theorist of anarchism during his lifetime, Kropotkin articulated its most systematic doctrine in an accessible manner, and he spearheaded the development of anarchist-communist social theory. His works, characterized by their inventiveness and pragmatism, became the most widely read anarchist books and pamphlets, translated into major European and Eastern languages. His ideas profoundly influenced not only revolutionaries such as Nestor Makhno and Emiliano Zapata, but also non-anarchist reformers like Patrick Geddes and Ebenezer Howard, as well as a wide range of intellectuals, including writers like Ba Jin and James Joyce. Much of Kropotkin's significant impact stemmed from his intellectual writings prior to 1914; despite his return, he had comparatively little direct influence on the Russian Revolution itself. He also notably contributed the article on anarchism to the eleventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica and left behind an unfinished work on anarchist ethical philosophy.

His ideas, alongside those of Mikhail Bakunin, are considered representative of late 19th-century Russian anarchism. Kropotkin's thought had a profound impact on early 20th-century East Asian anti-imperialist anarchists and independence activists. For instance, Shin Chae-ho in Korea was greatly influenced by Kropotkin's ideas, which led him to shift from a nationalist to an anarchist path for independence, and he subsequently helped disseminate Kropotkin's philosophy among Chinese and Korean anti-imperialist movements. Some historians even suggest that Mao Zedong, before 1919, was more influenced by Kropotkin's translated anarchist works than by Marxism-Leninism, with the People's Commune policy in China reportedly drawing inspiration from Kropotkin's concepts. In Japan, Kōtoku Shūsui resonated with anarchism and actively translated and distributed Kropotkin's books, demonstrating his significant impact on East Asian intellectual history in the early 20th century. While Kropotkin did not create anarcho-communism, he was instrumental in its development and popularization.

After his exile to England following his imprisonment in France on fabricated charges, Kropotkin's intellectual goal was to establish anarchist theory on a scientific basis. He became a reviewer for the prominent British science journal Nineteenth Century, where he consistently published socio-critical papers grounded in natural scientific thought. Consequently, his articles are still studied as important historical sources in the history of science from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution gained particular attention for challenging Social Darwinism and the concept of survival of the fittest, directly rebutting the arguments of contemporary British biologists and agnostics like Thomas Henry Huxley. However, after his return to Russia following the 1917 revolution, his later writings and activities were heavily censored by the Bolshevik regime, making their exact details less known.

4.2. Influence on Social Movements and Literature

Emma Goldman regarded Kropotkin as her "great teacher" and considered him among the greatest minds and personalities of the 19th century. His thought significantly influenced various social movements, reform efforts, and prominent intellectuals and writers across different countries, extending beyond the realm of political activism into literature.

4.3. Commemoration and Naming

After Kropotkin's death in 1921, the Bolsheviks initially permitted his Moscow house to be converted into a Kropotkin Museum. However, this museum was eventually closed in 1938, coinciding with his wife's death.

Kropotkin is the namesake for multiple geographical and urban entities, reflecting his significant contributions to geography and his enduring legacy. The Konyushennaya district in Moscow, where Kropotkin was born, is now known as the Kropotkinsky district, which includes the Kropotkinskaya metro station. A large town in the North Caucasus region of southwest Russia, Kropotkin, Krasnodar Krai, is named after him, as is a smaller town in Siberia, Kropotkin, Irkutsk Oblast. The Kropotkin Range in the Siberian Patom Highlands, which he was the first to traverse and scientifically document, bears his name. Furthermore, Mount Kropotkin, a peak in East Antarctica, was also named in his honor.

5. Works

5.1. Books

- In Russian and French Prisons (London: Ward and Downey, 1887)

- The Conquest of Bread (Paris, 1892)

- The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793 (French original: Paris, 1893; English translation: London, 1909)

- The Terror in Russia (1909)

- Words of a Rebel (1885)

- Fields, Factories, and Workshops (London and New York, 1898)

- Memoirs of a Revolutionist (London: Smith, Elder, 1899)

- Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (London, 1902)

- Modern Science and Anarchism (1903)

- Russian Literature: Ideals and Realities (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1905)

- The State: Its Historic Role (published 1946)

- Ethics: Origin and Development (unfinished, published 1948)

5.2. Pamphlets and Articles

- "An Appeal to the Young" (1880)

- "Communism and Anarchy" (1901)

- "Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles" (1887)

- "The Industrial Village of the Future" (1884)

- "Law and Authority" (1886)

- "The Coming Anarchy" (1887)

- "The Place of Anarchy in Socialist Evolution" (1886)

- "The Wage System" (1920)

- "The Commune of Paris" (1880)

- "Anarchist Morality" (1898)

- "Expropriation"

- "The Great French Revolution and Its Lesson" (1909)

- "Process Under Socialism" (1887)

- "Are Prisons Necessary?" (Chapter X from "In Russian and French Prisons") (1887)

- "The Coming War" (1913)

- "Wars and Capitalism" (1914)

- "Revolutionary Government" (1892)

- "The Scientific Basis of Anarchy" (1887)

- "The Fortress Prison of St. Petersburg" (1883)

- "Advice to Those About to Emigrate" (1893)

- "Some of the Resources of Canada" (1898)

- "Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal" (1896)

- "Revolutionary Studies" (1892)

- "Direct Action of Environment and Evolution" (1920)

- "The Present Crisis in Russia" (1901)

- "The Spirit of Revolt" (1880)

- "The State: Its Historic Role" (1897)

- "On Economics" (Selected Passages from his Writings) (1898-1913)

- "On the Teaching of Physiography" (1893)

- "War!" (1914)

- "The Constitutional Agitation in Russia" (1905)

- "Brain Work and Manual Work" (1890)

- "Manifesto of the Sixteen" (1916)

- "Organized Vengeance Called 'Justice.'"

- "A Proposed Communist Settlement: A New Colony for Tyneside or Wearside."

- "What Geography Ought to Be" (1885)

- "On Order"

- "Maxím Górky" (1904)

- "Research on the Ice age" (Notices of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, 1876)

- "Baron Toll" (The Geographical Journal, 1904)

- "The population of Russia" (The Geographical Journal, 1897)

- "The old beds of the Amu-Daria" (The Geographical Journal, 1898)

- "Russian Schools and the Holy Synod" (1902)

- "On Spherical Maps and Reliefs: Discussion" (The Geographical Journal, 1903)

- "The desiccation of Eur-Asia" (Geographical Journal, 1904)

- "Finland" (in Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., 1911)

- "Finland: A Rising Nationality" (Nineteenth Century, 1885)

- "Anarchism" (in Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., 1911)

- "Anti-militarism. Was it properly understood?" (Freedom, 1914)

- "An open letter of Peter Kropotkin to the Western workingmen" (The Railway Review, 1917)