1. Life

Paul Richards' life journey in baseball began at a young age, leading him through a professional playing career before he transitioned into influential roles as a manager and executive, where he left a lasting mark on the sport.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Paul Rapier Richards was born on November 21, 1908, in Waxahachie, Texas. He began his professional baseball career in the minor leagues in 1926 at the age of 17, starting as an infielder.

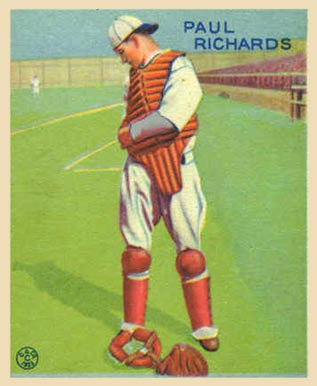

1.2. Playing Career

Richards spent seven years in the minor leagues before making his major league debut. His playing career was marked by strong defensive skills, particularly as a catcher, and a notable incident involving switch-pitching.

1.2.1. Minor League Career

Richards started his professional baseball journey as an infielder. On July 23, 1928, in a unique baseball event, he pitched with both hands for the Muskogee Chiefs of the Class C Western Association against the Topeka Jayhawks. Called from his shortstop position to the pitcher's mound, he pitched both right-handed and left-handed in a brief appearance. This included facing a switch hitter, which led to a brief stalemate as both pitcher and batter switched hands and batter's boxes, respectively, until Richards broke the pattern by alternating hands with each pitch. Later in his minor league career, he transitioned to playing catcher.

After playing for seven years in the minor leagues, Richards made his major league debut. He was later purchased by the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association in June 1932. In 78 games with Minneapolis, he achieved a .361 batting average. From 1938 to 1942, he served as a player-manager for the Atlanta Crackers, leading them to the pennant in 1938 and earning the title of minor league manager of the year from The Sporting News. He also played three more seasons as a player-manager with the Buffalo Bisons after his final major league stint, leading Buffalo to the International League pennant in 1949 before retiring as a player at the age of 40.

1.2.2. Major League Career

Richards made his Major League Baseball debut at the age of 23 with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 17, 1932. His contract was then purchased by the Minneapolis Millers in June 1932, and subsequently by John McGraw's New York Giants in September 1932. With the Giants, Richards served as a reserve catcher behind Gus Mancuso for the 1933 season. His future managing style was significantly influenced by his time playing for Giants manager Bill Terry, whose no-nonsense approach, focusing on pitching and defense, left a strong impression on Richards. The Giants went on to win the 1933 World Series, though Richards did not play in the post-season. After batting just .160 in 1934, he was traded in May 1935 to Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics. He caught the majority of the Athletics' games in 1935 before being traded to the Atlanta Crackers in November.

When professional baseball experienced a shortage of players during World War II, Richards returned to the major leagues in 1943 with the Detroit Tigers at the age of 34. While his batting average was a relatively low .220 in 100 games played, he excelled defensively, leading American League catchers in fielding percentage, range factor, baserunners caught stealing, and putouts, and finishing second in assists. Richards also served as an unofficial pitching coach for manager Steve O'Neill. His strong defensive play continued in 1944, where he again led the league's catchers in fielding percentage, range factor, and baserunners caught stealing percentage, and finished second in putouts and baserunners caught stealing as the Tigers narrowly missed the pennant on the last day of the season.

In 1945, Richards' batting average improved to a career-high .256. He once again led the league's catchers in fielding percentage and range factor as the Tigers won the American League championship, then defeated the Chicago Cubs in the 1945 World Series. In the deciding Game 7 of the series, he hit two doubles and had four runs batted in. Richards was the Tigers' starting catcher in six games of the seven-game series and contributed six runs batted in, second only to Hank Greenberg's seven. Despite his relatively low batting average, he finished 10th in the 1945 American League Most Valuable Player Award voting, largely due to his exceptional handling of the Tigers' pitching staff, which led the league in winning percentage, strikeouts, and shutouts, and finished second in earned run average. Richards was named one of The Sporting News All-Stars for 1945. After hitting only .201 in 1946, he returned to the minor leagues.

1.2.3. Playing Style and Statistics

Paul Richards was primarily known as an exceptional defensive catcher. He ended his major league career with a .987 fielding percentage. He led American League catchers three times in range factor, twice in fielding percentage, and once each in baserunners caught stealing and in caught stealing percentage. His career caught stealing percentage of 50.34% ranks 12th all-time among major league catchers.

Richards also demonstrated a keen baseball mind during his playing days. For example, in 1936, while playing for the Atlanta Crackers, he helped turn around pitcher Dutch Leonard's career by encouraging him to throw a knuckleball. Within two years, Leonard was back in the major leagues and became a 20-game winner in 1939.

In an eight-year major league career, Richards played in 523 games, accumulating 321 hits in 1,417 at bats for a .227 career batting average, along with 15 home runs and 155 runs batted in. In his 17 minor league seasons, he posted a career .295 batting average with 171 home runs.

1.3. Managing and Executive Career

Paul Richards transitioned from a successful playing career to an even more impactful managing and executive career, where he became known for his innovative strategies, player development skills, and team-building efforts across several Major League Baseball organizations.

1.3.1. Chicago White Sox

Richards became a successful manager with the Chicago White Sox in 1951. In an era when many teams relied on home runs for offensive production, Richards adopted a counter-intuitive strategy known as small ball, emphasizing pitching, strong defense, speed, and stolen bases to manufacture runs. During his first tenure, he was given the nickname "The Wizard of Waxahachie." The White Sox led the American League in stolen bases for 11 consecutive years from 1951 to 1961. Richards managed the White Sox to four winning seasons (1951, 1952, 1953, 1954), though his club consistently finished behind the dominant New York Yankees or the Cleveland Indians.

Richards returned to manage the White Sox in 1976 after a three-and-a-half-year hiatus from the game. After a losing record that season, he retired from on-field management but remained in baseball as a player personnel advisor with the White Sox and later the Texas Rangers.

1.3.2. Baltimore Orioles

In September 1954, Richards was hired by the Baltimore Orioles, where he served simultaneously as both field manager and general manager through 1958, becoming the first person since John McGraw to hold both positions concurrently. As general manager, he was involved in a significant 17-player trade with the New York Yankees, which remains the largest trade in baseball history. Richards focused his team-building efforts on acquiring good defensive players, such as Brooks Robinson, and hard-throwing young pitchers, including Steve Barber, Milt Pappas, and Chuck Estrada.

After Lee MacPhail was hired as the general manager in 1959, Richards continued solely as the Orioles' field manager. The team finally achieved significant success in 1960, finishing second in the American League after five seasons of rebuilding. This second-place finish was Richards' best as a manager. Both the Associated Press and United Press International named him the American League Manager of the Year for 1960. Richards led American League managers in ejections for 11 consecutive seasons from 1951 to 1961, setting an all-time managerial record. In September 1961, he resigned from the Orioles to take on a new executive role.

1.3.3. Houston Astros

After leaving the Orioles, Richards became the general manager of the new Houston Colt .45s National League club, which was later renamed the Houston Astros. Richards focused on stocking the team with promising young players, including future stars like Joe Morgan, Jimmy Wynn, Mike Cuellar, Don Wilson, and Rusty Staub. However, he was fired after the 1965 season when the team's on-field performance did not meet the expectations of owner Roy Hofheinz.

1.3.4. Atlanta Braves

The following year, in 1966, Richards was hired as the director of player personnel by the Atlanta Braves, marking his return to the city where he had excelled as a minor league catcher and player-manager for the Southern Association's Atlanta Crackers. By the end of the 1966 season, Richards was promoted to general manager of the Braves. His six years leading the Atlanta organization were among his most successful in baseball. He inherited a strong core of players, including Henry Aaron, Joe Torre, Felipe Alou, and Rico Carty. Richards further strengthened the team by adding several young pitchers and position players, and notably converted knuckleballing reliever Phil Niekro into a highly successful starter. His 1969 Braves, managed by his longtime protégé Luman Harris, won the National League Western Division title. However, that team was swept by the eventual world champion "Miracle Mets" in the first ever National League Championship Series. The Braves failed to contend in 1970 and 1971, and Richards was fired in the middle of the 1972 season, replaced by Eddie Robinson.

1.3.5. Managerial Tactics and Evaluation

Paul Richards was known for his innovative and sometimes unconventional managerial tactics. One such tactic, which he reintroduced and was erroneously credited with inventing, was dubbed "the Waxahachie Swap" by Rob Neyer of ESPN.com in 2009. This gambit, last seen in the major leagues in 1909, involved shifting a pitcher to the outfield and inserting a new pitcher to gain a platoon advantage, before returning the original pitcher to the mound. Richards employed this maneuver four or five times throughout his career.

Richards was also highly regarded for his player development skills. He was credited with helping Sherm Lollar become one of the best catchers in the major leagues and also assisted Gus Triandos in becoming a respectable catcher. He is famously known for designing the oversized catcher's mitt first used by Triandos to catch Hall of Fame knuckleball pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm.

Despite his skills as a motivator, mentor, and strategist, Richards never managed to lead a team to a pennant. However, his influence on the game was profound, as 16 of his players went on to become major league managers themselves, a testament to his ability to teach and inspire.

1.3.6. Managerial Record

Richards compiled a managerial record of 923 wins and 901 losses over 11 seasons.

| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| CWS | 1951 | 154 | 81 | 73 | .526 | 4th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CWS | 1952 | 154 | 81 | 73 | .526 | 3rd in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CWS | 1953 | 154 | 89 | 65 | .578 | 3rd in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CWS | 1954 | 145 | 91 | 54 | .627 | resigned | - | - | - | - |

| BAL | 1955 | 154 | 57 | 97 | .370 | 7th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BAL | 1956 | 154 | 69 | 85 | .448 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BAL | 1957 | 152 | 76 | 76 | .500 | 5th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BAL | 1958 | 153 | 74 | 79 | .484 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BAL | 1959 | 154 | 74 | 80 | .481 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BAL | 1960 | 154 | 89 | 65 | .578 | 2nd in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BAL | 1961 | 135 | 78 | 57 | .578 | resigned | - | - | - | - |

| BAL total | 1056 | 517 | 539 | .490 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| CWS | 1976 | 161 | 64 | 97 | .397 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CWS total | 768 | 406 | 362 | .529 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| Total | 1824 | 923 | 901 | .506 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

2. Death

Paul Richards died of a heart attack in his hometown of Waxahachie, Texas, on May 4, 1986, at the age of 77.

3. Legacy and Impact

Paul Richards left an indelible mark on baseball through his strategic innovations, dedication to player development, and the numerous individuals he influenced throughout his extensive career.

3.1. Contributions and Innovations

Richards' contributions to baseball are significant and varied. He was a pioneer in player development, notably helping to shape the careers of catchers like Sherm Lollar and Gus Triandos. His innovative thinking also led to the design of the oversized catcher's mitt, specifically created to help catchers handle the unpredictable movement of a knuckleball, first used by Triandos for Hoyt Wilhelm. Furthermore, he is widely credited with popularizing the 'small ball' strategy, which emphasized fundamental aspects of the game like pitching, defense, speed, and manufacturing runs, rather than solely relying on power hitting. His reintroduction of the "Waxahachie Swap" also showcased his willingness to employ unconventional tactics to gain a competitive edge.

3.2. Awards and Commemorations

Richards received several honors recognizing his impact on baseball. He was named one of The Sporting News All-Stars in 1945 for his exceptional performance as a catcher for the Detroit Tigers. In 1960, he was named the American League Manager of the Year by both the Associated Press and United Press International for leading the Baltimore Orioles to a second-place finish. In 1996, Richards was posthumously inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame. In his hometown, Paul Richards Park in Waxahachie has been designated a Texas Historical Landmark, commemorating his legacy.

3.3. Influence

Richards' lasting influence on baseball is perhaps best demonstrated by the number of players he mentored who went on to become managers themselves. Sixteen of his former players eventually became major league managers, a testament to his leadership qualities and his ability to impart strategic knowledge and a winning philosophy. His emphasis on pitching, defense, and 'small ball' strategies continued to influence team building and game management long after his active career concluded.