1. Overview

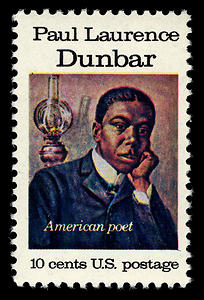

Paul Laurence Dunbar (June 27, 1872 - February 9, 1906) was a pioneering African-American poet, novelist, and short story writer who gained significant popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Dayton, Ohio, to parents who had been enslaved in Kentucky before the American Civil War, Dunbar began writing stories and verse as a child, publishing his first poems at the age of 16 in a Dayton newspaper. He quickly rose to prominence after his work received praise from William Dean Howells, a leading editor of Harper's Weekly, establishing him as one of the first African-American writers to achieve an international reputation.

Dunbar's extensive body of work includes numerous poetry collections, novels, and short stories, often exploring themes of racial prejudice and the lives of both Black and white Americans. While much of his popular work during his lifetime was written in African-American dialect, he also wrote extensively in conventional English and is recognized as the first important African-American sonnet writer. Beyond his literary contributions, Dunbar also wrote the lyrics for In Dahomey (1903), a groundbreaking musical comedy that was the first all-African-American production on Broadway. Despite his significant achievements, Dunbar's life was cut short by tuberculosis, and he died in Dayton, Ohio, at the age of 33.

2. Biography

Paul Laurence Dunbar's life was marked by both early challenges and remarkable literary success, shaped by his family's history and his own perseverance.

2.1. Early Life and Background

Paul Laurence Dunbar was born on June 27, 1872, at 311 Howard Street in Dayton, Ohio. His parents, Matilda and Joshua Dunbar, had both been enslaved in Kentucky before the American Civil War. After gaining their freedom, his mother, Matilda, relocated to Dayton with her two sons, Robert and William, from a previous marriage. Joshua Dunbar had escaped slavery in Kentucky before the war's conclusion, traveling to Massachusetts where he volunteered for the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first Black units to serve in the war. He also served in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment. Paul Dunbar was born six months after his parents' wedding on Christmas Eve, 1871.

The marriage between Joshua and Matilda was troubled, and Matilda left Joshua shortly after the birth of their second child, a daughter. Joshua Dunbar died on August 16, 1885, when Paul was 13 years old. His mother, Matilda, played a crucial role in his early education, having learned to read specifically to educate her children. She frequently read the Bible with him and hoped he would become a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black denomination in America.

2.2. Education and Early Influences

Dunbar was a precocious student, writing his first poem at the age of six and giving his first public recital at nine. During his time at Central High School in Dayton, he was the only African-American student. Despite this, he was well-accepted by his peers and formed a friendship with his classmate, Orville Wright. His academic and literary talents were recognized by his peers, leading to his election as president of the school's literary society. He also served as the editor of the school newspaper and was a member of the debate club.

2.3. Early Career and Development

At the age of 16, while still attending high school, Dunbar published his first poems, "Our Martyred Soldiers" and "On The River," in Dayton's The Herald newspaper in 1888. In 1890, he wrote and edited The Tattler, Dayton's first weekly African-American newspaper. It was printed by the fledgling company of his high-school acquaintances, Wilbur and Orville Wright, though the paper only lasted six weeks.

After completing his formal schooling in 1891, Dunbar took a job as an elevator operator, earning a meager salary of 4 USD a week. He harbored aspirations of studying law but was unable to pursue this dream due to his mother's limited finances and the prevalent racial discrimination of the era. These constraints motivated him to focus on his writing as a full-time profession. During this period, he met Eva Best, whose father had an architect's office in the same building where Dunbar worked. Best was among the first to recognize his poetic talent and was instrumental in introducing him to the public.

In 1892, Dunbar approached the Wright brothers about publishing his dialect poems in book form, but their company lacked the facilities for book printing. They suggested he go to the United Brethren Publishing House, which, in 1893, printed Dunbar's first collection of poetry, Oak and Ivy. Dunbar personally subsidized the printing of the book and quickly recouped his investment within two weeks by selling copies, often to passengers on his elevator. The book was divided into two sections: the larger "Oak" section featured traditional verse, while the smaller "Ivy" section contained lighter poems written in dialect. This work garnered the attention of James Whitcomb Riley, the popular "Hoosier Poet," who, like Dunbar, wrote in both standard English and dialect.

Recognizing his literary gifts, older benefactors stepped forward to offer financial assistance. Attorney Charles A. Thatcher offered to pay for Dunbar's college education, but Dunbar chose to continue pursuing his writing career, encouraged by the sales of his poetry. Thatcher helped promote Dunbar by arranging public readings of his poetry in Toledo at libraries and literary gatherings. Additionally, psychiatrist Henry A. Tobey assisted Dunbar by distributing his first book in Toledo and occasionally providing financial aid. Together, Thatcher and Tobey supported the publication of Dunbar's second verse collection, Majors and Minors (1896).

Despite frequently publishing poems and giving public readings, Dunbar struggled to financially support himself and his mother. Many of his efforts were unpaid, and his tendency for reckless spending often left him in debt by the mid-1890s. A turning point came on June 27, 1896, when the influential novelist, editor, and critic William Dean Howells published a favorable review of Majors and Minors in Harper's Weekly. Howells's endorsement brought national attention to Dunbar's writing. While Howells praised the "honest thinking and true feeling" in Dunbar's traditional poems, he particularly lauded the dialect poems, reflecting a contemporary appreciation for folk culture. This new literary fame enabled Dunbar to publish his first two books as a collected volume, titled Lyrics of Lowly Life, which included an introduction by Howells.

3. Literary Career and Achievements

Paul Laurence Dunbar's literary career was remarkably prolific despite its brevity, encompassing a wide range of forms and styles that explored the complexities of African-American life and American society.

3.1. Poetry and Prose

Dunbar was a highly productive writer during his relatively short career, publishing a dozen books of poetry, four books of short stories, four novels, and lyrics for a musical. His work is known for its meticulous craftsmanship in both his formal and dialect poetry, a trait that complemented the tune-writing abilities of composer Carrie Jacobs-Bond, with whom he collaborated on several songs.

His poetry collections include:

- Oak and Ivy (1892)

- Majors and Minors (1896)

- Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896)

- Lyrics of the Hearthside (1899)

- Poems of Cabin and Field (1899)

- The Haunted Oak (1900)

- Candle-lightin' Time (1901)

- Lyrics of Love and Laughter (1903)

- When Malindy Sings (1903)

- Li'l' Gal (1904)

- Howdy, Honey, Howdy (1905)

- Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (1905)

- Joggin' Erlong (1906)

Dunbar's short story collections often offered a "harsh examination of racial prejudice." His first collection, Folks From Dixie (1898), received favorable reviews. Other notable short story collections include The Strength of Gideon and Other Stories (1900), The Heart of Happy Hollow: A Collection of Stories, and In Old Plantation Days (1903).

His novels ventured into diverse subject matter, sometimes featuring white characters and society. His first novel, The Uncalled (1898), was described by critics as "dull and unconvincing" and was not a commercial success. In this novel, Dunbar explored the spiritual struggles of Frederick Brent, a white minister who was abandoned as a child by his alcoholic father and raised by a virtuous white spinster, Hester Prime. This work marked Dunbar as one of the first African Americans to cross the "color line (civil rights issue)" by writing a work solely about white society. His subsequent novels, The Love of Landry and The Fanatics, also explored white culture and were similarly criticized by some contemporary critics. The Fanatics centered on America at the beginning of the Civil War, focusing on white families with differing North-South sympathies in an Ohio community. However, literary critic Rebecca Ruth Gould argues that The Sport of the Gods (1902), one of his later novels, serves as a powerful lesson on the limiting power of shame on justice.

3.2. Literary Style and Techniques

Dunbar's literary style is characterized by his careful attention to craft in both his formal and dialect poetry. He was particularly proficient in the sonnet form and is considered the first important African-American sonnet writer. While he wrote much of his work in conventional English, he also utilized African-American dialect and regional dialects in some of his pieces.

Dunbar held complex feelings about the marketability of his dialect poems. He expressed weariness with dialect, feeling it might confine Black writers to a limited form of expression not associated with the educated class, stating, "I am tired, so tired of dialect." However, he also acknowledged, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces." He credited William Dean Howells for his early success but was dismayed by Howells's encouragement to focus primarily on dialect poetry. Dunbar felt that Howells's "dictum" on his dialect verse had caused him "irrevocable harm" by leading editors to refuse his more traditional poems. Dunbar's use of Negro dialect followed a literary tradition established by writers such as Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, and George Washington Cable.

Two brief examples illustrate the diversity of Dunbar's poetic works:

(From "Dreams")

:What dreams we have and how they fly

:Like rosy clouds across the sky;

:Of wealth, of fame, of sure success,

:Of love that comes to cheer and bless;

:And how they wither, how they fade,

:The waning wealth, the jilting jade -

:The fame that for a moment gleams,

:Then flies forever, - dreams, ah - dreams!

(From "A Warm Day In Winter")

:"Sunshine on de medders,

:Greenness on de way;

:Dat's de blessed reason

:I sing all de day."

:Look hyeah! What you axing'?

:What meks me so merry?

: 'Spect to see me sighin'

:W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary?

3.3. Dramatic and Musical Works

Dunbar extended his talents to musical theater, most notably through his collaboration on the groundbreaking musical comedy In Dahomey. He wrote the lyrics for the show, while Will Marion Cook composed the music and Jesse A. Shipp wrote the libretto. Produced on Broadway in 1903, In Dahomey was historically significant as the first musical written and performed entirely by African Americans. The production achieved considerable success, touring England and the United States for over four years, becoming one of the most successful theatrical productions of its time.

4. Social and Professional Life

Dunbar's life was interwoven with the prominent figures and social movements of his era, reflecting his commitment to both literary and civil rights advancement.

4.1. Relationships and Collaborations

Dunbar maintained a lifelong friendship with the Wright brothers, who had printed his early newspaper. Through his poetry, he became acquainted with influential Black leaders such as Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, and was close to his contemporary, writer James D. Corrothers. He also befriended Brand Whitlock, a journalist in Toledo who later pursued a political and diplomatic career.

In 1897, Dunbar embarked on a literary tour in England, where he recited his works on the London circuit. During this tour, he met the young Black composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who set some of Dunbar's poems to music, popularizing them. Coleridge-Taylor was inspired by Dunbar to incorporate African and American Negro songs and tunes into his future compositions. Also residing in London at the time, African-American playwright Henry Francis Downing arranged a joint recital for Dunbar and Coleridge-Taylor, held under the patronage of John Hay, who was then the American ambassador to Great Britain and a former aide to President Abraham Lincoln. Downing also provided lodging for Dunbar in London while the poet worked on his first novel, The Uncalled (1898).

4.2. Civil Rights Activism

Paul Laurence Dunbar was actively involved in civil rights initiatives and dedicated to the uplift and advancement of the African-American community. He participated in the March 5, 1897, meeting held to honor the memory of abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Attendees at this meeting worked towards the founding of the American Negro Academy under the leadership of Alexander Crummell, an organization dedicated to the intellectual and moral development of African Americans. His essays and poems were widely published in leading journals of the day, including Harper's Weekly, the Saturday Evening Post, the Denver Post, and Current Literature, often addressing themes pertinent to the Black experience.

5. Personal Life

Dunbar's personal life was marked by both significant relationships and profound health challenges that ultimately cut short his promising career.

5.1. Marriage and Health Decline

After returning from his literary tour in the United Kingdom, Paul Laurence Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore on March 6, 1898. Moore, a teacher and poet from New Orleans, had met Dunbar three years prior. Dunbar affectionately described her as "the sweetest, smartest little girl I ever saw." A graduate of Straight University (now Dillard University), a historically black college, Moore is best known for her short story collection, Violets. The couple also wrote books of poetry as companion pieces, and their love, life, and marriage were later portrayed in Oak and Ivy, a 2001 play by Kathleen McGhee-Anderson.

In October 1897, Dunbar took a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and he and Alice moved to the capital, settling in the comfortable LeDroit Park neighborhood. At his wife's urging, Dunbar soon left this position to dedicate himself fully to his writing, which he promoted through public readings. While in Washington, D.C., Dunbar also attended Howard University after the publication of Lyrics of Lowly Life.

In 1900, Dunbar was diagnosed with tuberculosis, a disease that was often fatal at the time. His doctors recommended drinking whisky to alleviate his symptoms and advised him to move to Colorado, as the cold, dry mountain air was considered beneficial for tuberculosis patients. Despite these efforts, Dunbar's health continued to decline. He and his wife separated in 1902 after an incident where he nearly beat her to death, though they never formally divorced. His struggles with depression and his deteriorating health led to a dependence on alcohol, which further exacerbated his physical condition.

6. Death

Paul Laurence Dunbar returned to Dayton, Ohio, in 1904 to live with his mother during his final years. He succumbed to tuberculosis on February 9, 1906, dying at the young age of 33. He was interred in the Woodland Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio.

7. Legacy and Impact

Paul Laurence Dunbar's influence extends far beyond his lifetime, cementing his place as a pivotal figure in American literature and African-American cultural history.

7.1. Critical Reception

Dunbar was the first African-American poet to achieve national distinction and widespread acceptance. The New York Times hailed him as "a true singer of the people - white or black." Frederick Douglass once referred to Dunbar as "one of the sweetest songsters his race has produced and a man of whom [he hoped] great things."

His friend and fellow writer James Weldon Johnson offered high praise for Dunbar in The Book of American Negro Poetry, published in 1931, following the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson stated that Paul Laurence Dunbar stood out as the first poet from the Negro race in the United States to show a combined mastery over poetic material and poetic technique, to reveal innate literary distinction in what he wrote, and to maintain a high level of performance. He was the first to rise to a height from which he could take a perspective view of his own race. Johnson added that Dunbar was the first to see objectively its humor, its superstitions, its shortcomings; the first to feel sympathetically its heart-wounds, its yearnings, its aspirations, and to voice them all in a purely literary form.

However, Johnson also offered a critique of Dunbar's dialect poems, suggesting that they had inadvertently fostered stereotypes of Black people as comical or pathetic, and reinforced the expectation that Black writers should primarily focus on scenes of antebellum plantation life in the South.

7.2. Influence on Later Generations

Dunbar's work has continued to inspire subsequent generations of writers, lyricists, and composers. Composer William Grant Still notably used excerpts from four of Dunbar's dialect poems as epigraphs for the four movements of his Symphony No. 1 in A-flat, "Afro-American" (1930). This symphony premiered the following year, marking it as the first symphony by an African American to be performed by a major orchestra for a U.S. audience. Dunbar's vaudeville song "Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd?" is believed by Dunbar scholar Hollis Robbins to have influenced the development of the popular chant "Who dat? Who dat? Who dat say gonna beat dem Saints?" associated with the New Orleans Saints football team.

Maya Angelou famously titled her autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) after a line from Dunbar's poignant poem "Sympathy". This title was suggested to her by jazz musician and activist Abbey Lincoln. Angelou stated that Dunbar's works had ignited her "writing ambition," and she frequently revisited his symbol of a caged bird as a metaphor for a chained slave throughout her own writings.

Dunbar's influence also extends to popular culture. In the movie Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit, the character Westley Glen 'Ahmal' James references Dunbar, encouraging classmates to "exhibit some pride in ourselves, like Paul Laurence Dunbar did." Additionally, in the 2016 Jim Jarmusch film Paterson, Method Man's character practices a rap that alludes to Dunbar.

7.3. Commemoration and Honors

Paul Laurence Dunbar's legacy is preserved and honored in numerous ways across the United States. His home in Dayton, Ohio, has been preserved as the Paul Laurence Dunbar House, a state historical site that is part of the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, administered by the National Park Service. His former residence in the LeDroit Park neighborhood of Washington, D.C. also still stands.

The Dunbar Library at Wright State University in Dayton holds a significant collection of Dunbar's papers. In 2002, Molefi Kete Asante included Paul Laurence Dunbar among his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Numerous schools and institutions across the country have been named in honor of Dunbar, including:

- High Schools:**

- Dunbar Creative and Performing Arts Magnet School in Mobile, Alabama

- Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Lexington, Kentucky

- Dunbar High School (Dayton, Ohio) in Dayton, Ohio

- Paul Laurence Dunbar High School (Baltimore, Maryland) in Baltimore, Maryland

- Dunbar Vocational High School in Chicago, Illinois

- Dunbar High Schools in Fort Myers, Florida, and Washington, D.C.

- Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Fort Worth, Texas

- Middle Schools:**

- Dunbar Middle Schools in Fort Worth, Texas, and Little Rock, Arkansas

- Paul Laurence Dunbar Middle School in Lynchburg, Virginia

- Paul Laurence Dunbar J.H.S 120/M.S. 301 in Bronx, New York

- Elementary Schools:**

- Dunbar elementary schools in Atlanta, Georgia; Memphis, Tennessee; Forest City, Kansas City, Kansas; East St. Louis, Illinois; and North Carolina

- Dunbar School (Fairmont, West Virginia) (which served elementary, middle, and high school levels)

- Libraries:**

- Paul Laurence Dunbar Library at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio

- Paul Laurence Dunbar Lancaster-Keist Branch Library in Dallas, Texas

- Other Institutions and Places:**

- Dunbar Hospital in Detroit, Michigan

- The Dunbar Hotel in Los Angeles, California

- Dunbar Apartments in Harlem, New York, built by John D. Rockefeller Jr. to provide housing for African Americans

- Dunbar Park (Chicago) in Chicago, Illinois, which features a statue of Dunbar created by sculptor Debra Hand and installed in 2014

- Paul Laurence Dunbar Lodge #19 in Brockton, Massachusetts

8. Bibliography

![1899 edition of [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Poems%20of%20cabin%20and%20field Poems of Cabin and Field]](https://cdn.onul.works/wiki/source/194fff29dc0_1b4a4da9.jpeg)

Paul Laurence Dunbar's major published works include:

Poetry collections

- Oak and Ivy (1892)

- Majors and Minors (1896)

- Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896)

- Lyrics of the Hearthside (1899)

- Poems of Cabin and Field (1899)

- The Haunted Oak (1900)

- Candle-lightin' Time (1901)

- Lyrics of Love and Laughter (1903)

- When Malindy Sings (1903)

- Li'l' Gal (1904)

- Howdy, Honey, Howdy (1905)

- Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (1905)

- Joggin' Erlong (1906)

Short stories and novels

- Folks From Dixie (1898), short story collection

- The Uncalled (1898), novel

- The Strength of Gideon and Other Stories (1900), short story collection

- The Love of Landry (1900), novel

- The Fanatics (1901), novel

- The Sport of the Gods (1902), novel

- In Old Plantation Days (1903), short story collection

- The Heart of Happy Hollow: A Collection of Stories (1904), short story collection

Articles

- "Representative American Negroes", in The Negro Problem, edited by Booker T. Washington, et al. (1903)