1. Early Life and Background

Pan Jun's early life laid the foundation for his distinguished career, marked by a strong academic background and early recognition of his talents.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Pan Jun was born in Hanshou County (漢壽縣Chinese), Wuling Commandery (武陵郡Chinese), which is located northeast of present-day Changde, Hunan, towards the end of the Eastern Han dynasty. Around the age of 20, he pursued his studies under the tutelage of the esteemed scholar Song Zhong (宋忠Chinese), also known as Song Zhongzi (宋仲子Chinese). Pan Jun quickly gained a reputation for his intelligence, keen observation skills, and his ability to provide well-reasoned and insightful responses to questions. His exceptional talent was recognized by Wang Can, one of the "Seven Scholars of Jian'an", who highly praised him. This commendation from a renowned intellectual significantly elevated Pan Jun's standing and made him more widely known within his home commandery.

1.2. Early Career

Following the recognition of his abilities, the Administrator of Wuling Commandery appointed Pan Jun as an Officer of Merit (功曹Chinese) to serve in the commandery office. Before he reached the age of 29, Liu Biao, the Governor of Jing Province (covering parts of present-day Hubei and Hunan), recruited him to serve as an Assistant Officer (從事Chinese) in Jiangxia Commandery (江夏郡Chinese), an area around present-day Xinzhou District, Wuhan, Hubei. During this period, the Chief of Shaxian County (沙羨縣Chinese), located within Jiangxia Commandery, was notorious for his rampant corruption and misgovernance. Pan Jun took decisive action, conducting a thorough investigation, finding the official guilty, and executing him according to the law. This act of strict and impartial justice sent shockwaves throughout Jiangxia Commandery, establishing Pan Jun's reputation for upholding the law without fear or favor. He was later reassigned to Xiangxiang County to serve as its Prefect (令Chinese), where he continued to earn widespread acclaim for his effective and principled governance.

2. Service under Liu Biao

Pan Jun's early career under Liu Biao in Jing Province was marked by his firm commitment to justice and good governance, establishing his reputation as an incorruptible official.

2.1. Assistant Officer in Jiangxia Commandery

As an Assistant Officer in Jiangxia Commandery, Pan Jun was confronted with significant corruption. The Chief of Shaxian County, a subordinate jurisdiction, was widely known for his dishonest practices and disregard for proper administration. Pan Jun, demonstrating his characteristic resolve, undertook an an investigation into the official's conduct. Upon confirming the Chief's guilt, Pan Jun, without hesitation, ordered his execution in strict accordance with the law. This decisive action had a profound impact, causing widespread awe and fear throughout Jiangxia Commandery, and solidified Pan Jun's image as an official who would not tolerate malfeasance.

2.2. Prefect of Xiangxiang County

Following his impactful tenure in Jiangxia, Pan Jun was appointed Prefect of Xiangxiang County. In this role, he continued to apply his principles of strict and fair governance. His administration in Xiangxiang was highly successful, earning him a strong reputation for effective and righteous leadership among the populace. The people of Xiangxiang held him in high regard due to his commitment to their well-being and the order he brought to the county.

3. Service under Liu Bei

Around late 209, when the warlord Liu Bei became the Governor of Jing Province, he recognized Pan Jun's administrative capabilities and appointed him to a significant role within his administration.

3.1. Role in Jing Province Administration

Liu Bei appointed Pan Jun as an Assistant Officer in the Headquarters Office (治中從事Chinese). Between 212 and 214, when Liu Bei embarked on a campaign to seize control of Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing) from its governor Liu Zhang, he entrusted Pan Jun with crucial responsibilities. Pan Jun was left behind to assist Liu Bei's general Guan Yu in guarding Liu Bei's territories in Jing Province and overseeing daily administrative affairs. This appointment demonstrated Liu Bei's trust in Pan Jun's ability to manage provincial matters effectively in his absence.

3.2. Relationship with Guan Yu

While Pan Jun was entrusted with significant administrative duties in Jing Province alongside Guan Yu, historical accounts suggest that their relationship was not particularly close. Although Liu Bei placed great confidence in Pan Jun, Guan Yu did not seek to form a close personal bond with him. This dynamic is further highlighted in the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, where Wang Fu explicitly warns Guan Yu against leaving Pan Jun in charge, describing him as a selfish and jealous individual. However, Guan Yu dismisses these concerns, stating his confidence in Pan Jun's character. This fictional portrayal contrasts with historical records that generally praise Pan Jun's integrity, but it underscores a historical perception of a lack of close rapport between Pan Jun and Guan Yu.

4. Service under Sun Quan

Pan Jun's most significant contributions came during his long and impactful service under Sun Quan, where he played a crucial role in military campaigns and high-level administration for the state of Eastern Wu.

4.1. Joining Sun Quan

Between November 219 and February 220, Sun Quan broke his alliance with Liu Bei and launched a stealth invasion of Liu Bei's territories in Jing Province, led by his general Lü Meng. After Guan Yu's defeat and execution, Sun Quan gained control of Jing Province. Most of Liu Bei's officials in the province quickly surrendered and pledged allegiance to Sun Quan. However, Pan Jun initially resisted, claiming illness and refusing to leave his home. Sun Quan, recognizing Pan Jun's exceptional talent, sent his servants to Pan Jun's residence to carry him, still lying on his bed, to Sun Quan's presence. Pan Jun remained face down, weeping disconsolately. Sun Quan personally comforted him, comparing Pan Jun's situation to that of Guan Dingfu and Peng Zhongshuang, two famous statesmen from the ancient state of Chu who, despite being captives, were appointed to high positions by the Kings of Chu. Sun Quan asked if Pan Jun believed he lacked the magnanimity of these ancient kings. He then ordered his servants to wipe away Pan Jun's tears. Pan Jun finally rose, knelt, and agreed to serve Sun Quan. Impressed by his integrity and loyalty, Sun Quan immediately appointed him as an Attendant Official at Headquarters (治中Chinese) and frequently consulted him on matters concerning Jing Province. Soon after, Pan Quan commissioned Pan Jun as General of the Household Who Assists the Army (輔軍中郎將Chinese) and placed him in command of troops.

4.2. Quelling the Wuling Rebellion

In early 220, Fan Zhou (樊伷Chinese), a former official in Wuling Commandery, incited the indigenous tribes in Wuling to rebel against Sun Quan. Before 221, Xi Zhen (習珍Chinese), a former colleague of Pan Jun, also declared himself Administrator of Shaoling and publicly announced his support for Liu Bei's eastern invasion of Wu. When other officials suggested that at least 10,000 troops were needed to suppress the rebellion, Sun Quan sought Pan Jun's opinion. Pan Jun confidently stated that 5,000 troops would be sufficient. When asked for his reasoning, Pan Jun explained that Fan Zhou, despite his eloquent words, lacked true oratorical talent and practical ability, citing an anecdote where Fan Zhou failed to prepare a feast by midday, causing guests to leave. Sun Quan, amused and convinced, accepted Pan Jun's assessment. Pan Jun led 5,000 troops and successfully eliminated Fan Zhou, quelling the rebellion. He also attempted to persuade Xi Zhen to surrender, but Xi Zhen refused. As a reward for this swift and effective suppression, Pan Jun was promoted to General of Vehement Might (奮威將軍Chinese) and enfeoffed as the Marquis of Changqian Village (常遷亭侯Chinese). He later took over command of the troops of the deceased Rui Xuan (芮玄Chinese) and garrisoned them at Xiakou (夏口Chinese), in present-day Wuhan, Hubei. Furthermore, Pan Jun was noted for incorporating a large number of surrendered Wuling indigenous people into his army, leading a powerful force.

4.3. Military Achievements and Promotions

Pan Jun's military prowess and administrative capabilities led to a series of promotions and honors under Sun Quan. After successfully quelling the rebellion in Wuling Commandery, he was promoted to General of Vehement Might and enfeoffed as the Marquis of Changqian Village. In 229, when Sun Quan declared himself emperor of Eastern Wu, Pan Jun was appointed Minister Steward (少府Chinese) and his peerage was elevated from a village marquis to a county marquis, receiving the title "Marquis of Liuyang" (劉陽侯Chinese). His military leadership was further demonstrated during the campaign against the Wuxi tribes, where he held acting imperial authority.

4.4. Ministerial and Administrative Roles

Following his appointment as Minister Steward, Pan Jun was soon promoted to Minister of Ceremonies (太常Chinese) and stationed in Wuchang (武昌Chinese), present-day Ezhou, Hubei. While in Wuchang, he shared responsibility for civil and military affairs in Jing Province with the esteemed Wu general Lu Xun. This joint leadership underscored the high level of trust Sun Quan placed in both men to manage critical regional matters. Pan Jun's administrative acumen ensured that promises were kept and that rewards and punishments were dispensed fairly, contributing to stability and order in the areas under his jurisdiction.

4.5. Suppressing Tribal Rebellions

Around March or April 231, the indigenous tribes residing in Wuxi (五谿Chinese), an area around present-day Huaihua, Hunan, rebelled against Wu rule. Sun Quan granted Pan Jun acting imperial authority and ordered him to supervise General Lü Dai as Lü Dai led 50,000 troops to pacify the rebellion. Generals Lü Ju (呂據Chinese), Zhu Ji (朱績Chinese), and Zhongli Mu (鍾離牧Chinese) also participated in the campaign. Pan Jun ensured that military discipline was strictly enforced, and that rewards and punishments were applied impartially. The campaign was arduous, lasting until December 234, and at one point, Zhongli Mu's forces faced such a difficult situation that they nearly had to be abandoned. However, it ultimately resulted in a decisive victory for Eastern Wu. Over 10,000 rebels were either killed or taken captive, and the indigenous tribes were so severely weakened that they were unable to mount another significant rebellion for a considerable period, bringing lasting peace to the region.

4.6. Dealing with Lü Yi's Abuses of Power

In the 230s, Lü Yi was appointed by Sun Quan as the supervisor of the bureau responsible for auditing and reviewing the work of all officials throughout Eastern Wu. This bureau functioned akin to a secret service and was a precursor to the censorate of later Chinese dynasties. Lü Yi, however, flagrantly abused his extensive powers, falsely accusing many officials of serious offenses, leading to their wrongful arrest, imprisonment, and torture. Among his prominent victims were the Imperial Chancellor Gu Yong and General Zhu Ju. When Zheng Zhou (鄭冑Chinese), the Administrator of Jian'an, was imprisoned due to Lü Yi's slander, Pan Jun, along with Chen Biao (陳表Chinese), successfully persuaded Sun Quan to acquit him.

Lü Yi initially intended to build a case against Gu Yong for incompetence, hoping to have him removed from office. However, an official named Xie Gong (謝厷Chinese) subtly reminded Lü Yi that Pan Jun, the Minister of Ceremonies, was the most likely candidate to succeed Gu Yong as Imperial Chancellor. Lü Yi, knowing Pan Jun's strong resentment towards him, immediately dropped the charges against Gu Yong, fearing Pan Jun's retaliation if he ascended to the chancellorship.

Pan Jun, determined to confront Lü Yi, sought and obtained permission from Sun Quan to return to the imperial capital, Jianye (present-day Nanjing, Jiangsu), from his post in Wuchang. Although he intended to speak out against Lü Yi's abuses of power, he became increasingly frustrated when he observed that Sun Quan was not heeding the repeated concerns voiced by the crown prince, Sun Deng, regarding Lü Yi. Driven by a deep concern for the state, Pan Jun devised a drastic plan: he pretended to host a grand banquet, inviting all his colleagues, with the intention of personally assassinating Lü Yi during the gathering. He viewed Lü Yi as a grave threat to Eastern Wu. However, Lü Yi caught wind of Pan Jun's plot and feigned illness to avoid attending the banquet.

Despite the failure of his assassination attempt, Pan Jun did not cease his efforts. He consistently spoke up about Lü Yi's wicked deeds whenever he had an audience with Sun Quan. Over time, Lü Yi's influence and Sun Quan's trust in him waned. His abuses of power were eventually fully exposed in 238. Sun Quan removed Lü Yi from office, ordered Gu Yong to conduct a thorough investigation into his crimes, and subsequently had him executed. Following the scandal, Sun Quan publicly acknowledged his own error in not heeding earlier advice and urged his senior officials to continue pointing out his mistakes. Pan Jun, along with Lu Xun, shed tears and acted distressed, which made Sun Quan uneasy. This incident served as a testament to Pan Jun's persistent advocacy for justice.

5. Political Principles and Integrity

Pan Jun was widely celebrated for his unwavering commitment to justice, his personal integrity, and his courage in confronting corruption, embodying the ideal of a principled official.

5.1. Upholding the Law and Personal Integrity

Pan Jun earned a formidable reputation as an honest official who strictly and fairly enforced the law, regardless of personal connections or potential repercussions. His adherence to legal principles was absolute, and he was known for not fearing public opinion or private influence when carrying out his duties. A notable example of his uncompromising stance was his handling of Xu Zong (徐宗Chinese), a general from Yuzhang Commandery who was well-known among the literati and a friend of Kong Rong. When Xu Zong visited the Wu imperial capital, Jianye, he allowed his subordinates to behave lawlessly, disregarding regulations. Pan Jun, upon learning of these transgressions, ordered Xu Zong's arrest and execution for breaking the law. This incident, among others, demonstrated Pan Jun's unwavering commitment to the rule of law and his refusal to tolerate misconduct, even from influential figures.

5.2. Advising Sun Quan

Pan Jun frequently offered astute counsel to Sun Quan, demonstrating his foresight and dedication to good governance. On one occasion, Sun Quan, who was fond of pheasant hunting, was advised by Pan Jun to cease the activity. When Sun Quan remarked that he only hunted occasionally, Pan Jun explained that with the empire still unsettled and numerous state affairs demanding attention, pheasant hunting was not an urgent matter. He added that damaged bows and broken bowstrings during hunting could become significant problems during wartime. Pan Jun then dramatically destroyed his own parasol, which was made from pheasant feathers, as a symbolic gesture. Sun Quan, moved by Pan Jun's sincerity and reasoning, subsequently stopped pheasant hunting entirely.

Another instance of his wise counsel involved General Bu Zhi, who, stationed at Oukou (漚口Chinese) between 226 and 230, sought permission from Sun Quan to recruit men from various commanderies in southern Jing Province to augment his army. When Sun Quan consulted Pan Jun, the latter advised against it, stating that "overbearing generals given access to the common people will cause harm and chaos to them." He further cautioned that Bu Zhi's fame was inflated by flattery, making his request dangerous. Sun Quan heeded Pan Jun's advice, preventing a potential concentration of power that could destabilize the region. These instances highlight Pan Jun's commitment to the long-term stability and well-being of the state, often prioritizing it over the immediate desires of the emperor or powerful generals.

6. Personal Life and Family

Pan Jun's personal life was intertwined with prominent figures of his time, and his family continued his legacy of service.

6.1. Family Relations

Pan Jun had notable familial connections, including his maternal cousin Jiang Wan, a senior official of Wu's ally state, Shu Han. This distant familial tie led to a curious incident around March or April 231. Wei Jing (衞旌Chinese), the Wu-appointed Administrator of Wuling Commandery, reported to Sun Quan that Pan Jun had been secretly communicating with Jiang Wan, implying an intention to defect to Shu. Sun Quan, however, displayed immense trust in Pan Jun, dismissing the report with the remark, "Chengming won't do this." He then sealed Wei Jing's report and personally showed it to Pan Jun, simultaneously removing Wei Jing from office and recalling him to the imperial capital, Jianye. This act underscored Sun Quan's profound confidence in Pan Jun's loyalty and integrity, despite the serious accusation.

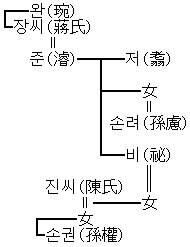

6.2. Marriage and Children

Pan Jun's daughter was married to Sun Lü, the Marquis of Jianchang, who was Sun Quan's second son. This marriage further solidified Pan Jun's connection to the imperial family, though Sun Lü died young in 232.

Pan Jun had two sons: Pan Zhu (潘翥Chinese) and Pan Mi (潘祕Chinese). His elder son, Pan Zhu, whose courtesy name was Wenlong (文龍Chinese), was commissioned as a Cavalry Commandant (騎都尉Chinese) and held command of troops. However, Pan Zhu died early in his career. The younger son, Pan Mi, married Ms. Chen (陳氏Chinese), a half-sister of Sun Quan, further strengthening the family's imperial ties. Pan Mi served as the Prefect of Xiangxiang County, a position his father had also held with distinction. He later rose to the significant position of Supervisor of the Masters of Writing (尚書僕射Chinese) and eventually succeeded Xi Wen (習溫Chinese) from Xiangyang as the Grand Rectifier (大公平Chinese) of Jing Province, a role akin to a provincial chief censor. Pan Mi was highly regarded in Jing Province for his administration. An anecdote recounts Pan Mi visiting Xi Wen and asking who would succeed him as Grand Rectifier, to which Xi Wen replied, "None other than you," a prediction that came true.

7. Anecdotes and Historical Evaluation

Pan Jun's character was illuminated by several notable anecdotes, and his career received significant historical assessments, largely praising his integrity and effectiveness.

7.1. Character-Revealing Anecdotes

Pan Jun's strict adherence to principles extended to his family. His son, Pan Zhu, befriended Yin Fan (隱蕃Chinese), an official who had defected from Eastern Wu's rival state, Wei, and was known for his eloquence, which earned him the favor of many Wu officials. Pan Zhu even sent gifts to Yin Fan. When Pan Jun discovered this, he was enraged and wrote a stern letter to his son. In the letter, he emphasized his own deep gratitude and commitment to the state, stating that his son, while in the imperial capital, should behave respectfully, humbly, and seek ties with virtuous and wise individuals, rather than associating with a defector from a rival state and sending him provisions. Pan Jun expressed his shock, anger, and worry, and ordered his son to receive 100 flogs from the authorities and retrieve the gifts from Yin Fan. At the time, many found Pan Jun's reaction excessively harsh. However, when Yin Fan was later executed for plotting rebellion against Wu, everyone realized the wisdom and foresight behind Pan Jun's strictness, affirming his judgment.

7.2. Historical Assessments

Pan Jun consistently received high praise from historians and contemporaries for his integrity and effectiveness. Bu Zhi (步騭Chinese) himself held Pan Jun in high regard. Chen Shou, the author of the Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi), lauded Pan Jun, stating that he was "publicly clear and decisive... all of them were firm in their principles and had the achievements of great men." This assessment highlights Pan Jun's selflessness and his unwavering commitment to the state. Lu Ji in his Bianwang Lun also praised Pan Jun, alongside figures like Gu Yong, Lü Fan, and Lü Dai, for his significant political contributions to Eastern Wu.

However, there is a contrasting assessment from Yang Xi's Jihan Fuchen Zan (Eulogy for the Shu Han Retainers). This work grouped Pan Jun with figures like Mi Fang, Shi Ren, and Hao Pu, implying a perception of him as a "traitor" or "laughingstock" in the context of the Shu-Wu relationship, particularly given his initial service under Liu Bei before joining Sun Quan. This perspective, though less common in overall historical evaluations, reflects the strong sentiments and rivalries of the Three Kingdoms period and the differing loyalties expected by each state. Despite this specific criticism, the predominant historical view, particularly from Wu-centric sources, emphasizes Pan Jun's integrity, administrative skill, and military acumen, recognizing him as a bold and honest official who fearlessly upheld the law.

8. In Popular Culture

Pan Jun appears as a minor character in the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which romanticizes the historical events of the Three Kingdoms period.

8.1. Depiction in Romance of the Three Kingdoms

In the novel, Pan Jun is depicted as a subordinate of Guan Yu. When Guan Yu prepares to depart for the Battle of Fancheng, he leaves Pan Jun behind to guard Liu Bei's territories in Jing Province. However, Wang Fu attempts to dissuade Guan Yu from this decision, warning that Pan Jun is a selfish and jealous person who cannot be trusted. Wang Fu recommends Zhao Lei (趙累Chinese), the frontline supply officer, as a more loyal and honest alternative. Despite this strong warning, Guan Yu dismisses Wang Fu's concerns, stating that he knows Pan Jun's character well and that changing assignments would be too troublesome. He also accuses Wang Fu of being overly suspicious. This portrayal in the novel diverges from historical accounts, which generally depict Pan Jun as an upright and capable official. In the novel, Pan Jun's subsequent quick surrender to Lü Meng during the fall of Jing Province is presented as a validation of Wang Fu's initial warning, contributing to a more negative perception of his character compared to historical records.

9. Death

Pan Jun died in 239. His peerage, the Marquis of Liuyang, was inherited by his elder son, Pan Zhu. However, Pan Zhu died early, and the peerage was then passed to Pan Jun's younger son, Pan Mi. Lü Dai (呂岱Chinese) succeeded Pan Jun in his duties in Wuchang.