1. Overview

Otto I, often known as **Otto the Great** (Otto der GroßeOtto the GreatGerman), reigned as King of Germany from 936 and was crowned the first Holy Roman Emperor in 962, a title he held until his death in 973. Born in 912 as the eldest son of Henry the Fowler, founder of the Ottonian dynasty, Otto inherited the Duchy of Saxony and the German kingship, continuing his father's ambitious work of unifying the diverse German tribes into a cohesive realm. He significantly expanded royal power at the expense of the aristocracy, employing strategic marriages and personal appointments to install loyal family members in key ducal positions.

Otto's reign was marked by his innovative use of the Church to bolster royal authority, a system known as the Imperial Church System, where clergy were appointed to secular offices, creating a loyal bureaucracy. He decisively suppressed a series of internal rebellions, including a significant civil war led by his own son, Liudolf, Duke of Swabia. His military prowess was most famously demonstrated in the pivotal Battle of Lechfeld in 955, where he defeated the Magyars, effectively ending their invasions of Western Europe and earning him the reputation as a "savior of Christendom."

His expansionist policies led him to conquer the Kingdom of Italy in 961. Following the precedent of Charlemagne, Otto was crowned Emperor by Pope John XII in Rome in 962, marking a significant revival of the imperial title and the unification of the German and Italian realms into what would later be known as the Holy Roman Empire. His later years involved complex relations with the papacy, asserting imperial authority over papal elections, and diplomatic efforts to gain recognition from the Byzantine Empire, culminating in the marriage of his son, Otto II, to the Byzantine princess Theophanu. Otto I's enduring legacy lies in his consolidation of the German kingdom, the restoration of the imperial title, and his profound influence on the political and cultural landscape of medieval Europe, fostering a period of cultural revival known as the Ottonian Renaissance.

2. Early Life and Background

Otto I's early life laid the foundation for his formidable reign, shaped by his powerful family and the political landscape of the nascent German kingdom.

2.1. Birth and Family

Otto I was born on 23 November 912, likely in Wallhausen, Saxony. He was the eldest son of Henry the Fowler, then Duke of Saxony and later King of East Francia, and his second wife, Matilda of Ringelheim, daughter of Dietrich, a Saxon count in Westphalia. Otto had four full siblings: Hedwig, Gerberga, Henry, and Bruno.

His father, Henry, had previously married Hatheburg of Merseburg in 906, with whom he had a son, Thankmar, Otto's half-brother. This marriage was annulled around 909, reportedly for reasons of family prestige and the adjustment of the wife's status after Henry became the heir apparent to the Duchy of Saxony due to his elder brother's early death. Otto also had an illegitimate son, William, born in 929 to a captive Wendish noblewoman, who would later become Archbishop of Mainz.

2.2. Rise of the Ottonians

The Ottonian dynasty's ascent began with Otto's father, Henry the Fowler. On 23 December 918, Conrad I, King of East Francia and Duke of Franconia, died without a direct heir. According to the Saxon chronicler Widukind of Corvey in The Deeds of the Saxons, Conrad, despite his earlier conflicts with Henry, persuaded his younger brother, Eberhard of Franconia, to offer the crown of East Francia to Henry. After several months of deliberation, Eberhard and other Frankish and Saxon nobles elected Henry as king at the Imperial Diet of Fritzlar in May 919. This marked a significant shift, as for the first time, a Saxon, rather than a Frank, reigned over the kingdom.

Henry I successfully consolidated power by binding the powerful duchies of Swabia and Bavaria to his kingdom through military submission and subsequent "friendship pacts" (Latin: amicitia). Burchard II of Swabia swore fealty, while Arnulf of Bavaria, who initially opposed Henry and was even elected as a rival king by the Bavarians, was defeated in two campaigns in 921 and forced to submit. Bavaria retained some autonomy, including the right to invest bishops, but acknowledged Henry's sovereignty. By 925, Henry had also successfully incorporated Lotharingia (Lorraine), which had previously been allied with West Francia, into East Francia.

2.3. Preparation for Succession

![The confraternity book of the Abbey of Reichenau records the names of the Ottonian family and their most important helpers from 929. In the second column from the right Heinricus rex and his wife Mathild[e] reg[ina] are listed, then their eldest son Otto rex, already with the title of king.](https://cdn.onul.works/wiki/source/197d1fd103e_6ea9473e.jpg)

Otto gained early military experience fighting against Wendish tribes on the eastern border of the German kingdom. By 929, with Henry's dominion over the kingdom secured, the king began preparing for his succession. Although no formal written evidence of his arrangements exists, Otto is first referred to as "king" (Latin: rex) in the confraternity book of the Abbey of Reichenau during this period, indicating his designation as heir. He was also said to have received an anointing ceremony in Mainz in early 930.

To strengthen the Ottonian dynasty's legitimacy and forge an alliance with Anglo-Saxon England, Henry sought a royal bride for Otto. King Æthelstan of England sent two of his half-sisters to Henry, who chose Eadgyth as Otto's bride. They were married in 930 in Quedlinburg. As a "morning gift" (Morgen GabeMorning GiftGerman), Otto presented Magdeburg to his new wife, a place significant to him from his youth and which would later become a crucial base for his eastern expansion.

Several years later, shortly before Henry's death, an Imperial Diet at Erfurt formally ratified the succession arrangements. While some estates and treasures were distributed among his sons Thankmar, Henry, and Bruno, Henry departed from the customary Carolingian inheritance practice of dividing the kingdom among all sons. Instead, he designated Otto as the sole heir apparent, without requiring a prior formal election by the various dukes, aiming for a united kingdom under a single ruler.

3. Reign as King of Germany

Otto I's reign as King of Germany was characterized by his efforts to centralize royal authority, suppress internal opposition, and secure the kingdom's borders against external threats.

3.1. Coronation

Henry the Fowler died from a cerebral stroke on 2 July 936 at his palace in Memleben, and was buried at Quedlinburg Abbey. At the time of his death, all the various German tribes were united under a single realm. At nearly 24 years old, Otto assumed his father's position as Duke of Saxony and King of Germany. His coronation was held on 7 August 936 in Charlemagne's former capital of Aachen, where he was anointed and crowned by Hildebert, the Archbishop of Mainz. Although Saxon by birth, Otto appeared at the coronation in Frankish dress, a deliberate act to demonstrate his sovereignty over the Duchy of Lotharingia and assert his role as the true successor to Charlemagne, whose last heirs in East Francia had died out in 911.

According to Widukind of Corvey, Otto had the four other dukes of the kingdom-from the duchies of Franconia, Swabia, Bavaria, and Lorraine-serve as his personal attendants at the coronation banquet. Arnulf I of Bavaria acted as marshal, Herman I of Swabia as cupbearer, Eberhard of Franconia as steward, and Gilbert of Lorraine as chamberlain. By performing these traditional services, the dukes publicly signaled their cooperation with the new king and clearly demonstrated their submission to his reign.

3.2. Consolidation of Power

Despite a seemingly peaceful transition, Otto's early reign was marked by internal strife within the royal family and among the nobility. Otto's younger brother, Henry, also claimed the throne, contrary to their father's wishes. Their mother, Matilda, reportedly favored Henry, as he was "born in the purple" during their father's reign and shared his name. Otto's authoritarian style, which contrasted sharply with his father Henry's approach of treating dukes as "first among equals" and relying on "friendship pacts," also generated discontent among the nobility. Otto, having accepted Church anointment, viewed his kingdom as a feudal monarchy with a "divine right" to rule, and he deliberately ignored claims of dynastic succession in favor of appointing individuals loyal to him.

3.2.1. Conflicts with Nobility and Brothers

Otto faced immediate opposition from various local aristocrats. In 936, he appointed Hermann Billung as Margrave, granting him authority over a march north of the Elbe River between the Limes Saxoniae and Peene Rivers. This appointment angered Hermann's elder and wealthier brother, Count Wichmann the Elder, who believed his claim was superior. Otto further offended the nobility in 937 by appointing Gero to succeed his older brother Siegfried as Count and Margrave of a vast border region around Merseburg. Otto's half-brother, Thankmar, who felt he had a greater right to the appointment, was also frustrated.

The death of Arnulf, Duke of Bavaria, in 937 led to further conflict. His son and successor, Eberhard, refused to recognize Otto's supremacy over Bavaria. In two campaigns in 938, Otto defeated and exiled Eberhard, stripping him of his titles. Otto then appointed Eberhard's uncle, Berthold, as the new Duke of Bavaria, on condition that Berthold recognize Otto's sole authority to appoint bishops and administer royal property within the duchy.

Around the same time, Otto mediated a dispute between Bruning, a Saxon noble, and Duke Eberhard of Franconia. Eberhard had attacked Bruning's castle, killing its inhabitants and burning it down, because Bruning refused to swear fealty to a non-Saxon ruler. Otto summoned both parties to his court in Magdeburg, where Eberhard was fined, and his lieutenants were subjected to the humiliating punishment of publicly carrying dead dogs.

3.2.2. Suppression of Rebellions

Infuriated by Otto's actions, Eberhard of Franconia joined Otto's half-brother Thankmar, Count Wichmann, and Archbishop Frederick of Mainz in rebellion in 938. Duke Herman I of Swabia, a close advisor to Otto, warned him of the revolt, allowing Otto to move swiftly. Wichmann soon reconciled with Otto and joined the royal forces. Otto besieged Thankmar at Eresburg, and though Thankmar surrendered, he was killed by a common soldier. Otto mourned his half-brother but did not punish the killer. Following their defeats, Eberhard and Frederick sought reconciliation and were pardoned by Otto after a brief exile in Hildesheim, being restored to their positions.

Shortly after his reconciliation, Eberhard planned a second rebellion. He promised to aid Otto's younger brother Henry in claiming the throne and recruited Gilbert, Duke of Lorraine, who was married to Otto's sister Gerberga but had sworn fealty to King Louis IV of West Francia. Otto exiled Henry, who fled to Louis IV's court. Louis, hoping to regain influence over Lorraine, allied with Henry and Gilbert. In response, Otto allied with Louis's chief rival, Hugh the Great, Count of Paris, who was married to Otto's sister Hedwige.

Henry captured Merseburg, but Otto besieged the rebels at Chevremont near Liège. Otto then moved against Louis IV, who had seized Verdun, driving him back to Laon. Despite initial victories, Otto could not capture the main conspirators. Archbishop Frederick attempted to mediate peace, but Otto rejected his terms. Duke Herman of Swabia led an army into Franconia and Lorraine. Otto's allies from the Duchy of Alsace crossed the Rhine River and surprised Eberhard and Gilbert at the Battle of Andernach on 2 October 939. Otto's forces achieved an overwhelming victory: Eberhard was killed, and Gilbert drowned in the Rhine while attempting to escape. Henry submitted to Otto, ending the rebellion. Otto then assumed direct rule over the Duchy of Franconia, dissolving it into smaller counties and bishoprics directly accountable to him. That same year, Otto made peace with Louis IV, who recognized Otto's suzerainty over Lorraine. In return, Otto withdrew his army and arranged for his widowed sister Gerberga to marry Louis IV.

In 940, Otto and Henry were reconciled through their mother's efforts. Henry returned to East Francia, and Otto appointed him as the new Duke of Lorraine. However, Henry still harbored ambitions for the German throne and, with Archbishop Frederick of Mainz, plotted to assassinate Otto on Easter Day 941 at Quedlinburg Abbey. Otto discovered the plot, arrested the conspirators, and imprisoned them at Ingelheim. He later released and pardoned both Henry and Frederick after they publicly performed penance on Christmas Day.

3.2.3. Governance through Family Ties

The decade between 941 and 951 marked Otto's period of undisputed domestic power. He asserted his authority to make decisions without the prior agreement of the dukes, deliberately ignoring the nobility's claims to dynastic succession in favor of appointing individuals of his own choice based on loyalty. His mother, Matilda, disapproved of this policy and was briefly exiled in 947 before being recalled to court at the urging of Otto's wife, Eadgyth.

Otto's new policy ensured his position as the kingdom's undisputed master. Rebellious family members and aristocrats were compelled to publicly confess their guilt and unconditionally surrender, often hoping for a royal pardon. Otto's punishments for nobles and high-ranking officials were typically mild, and they were usually restored to positions of authority. His brother Henry, for instance, rebelled twice and was pardoned twice, even being appointed Duke of Lorraine and later Duke of Bavaria. Rebellious commoners, however, were treated far more harshly, often executed.

Otto continued to reward loyal vassals. While appointments remained at his discretion, they became increasingly intertwined with dynastic politics. Unlike Henry, who relied on "friendship pacts," Otto relied on family ties. He refused to accept uncrowned rulers as his equals and integrated important vassals through marriage. King Louis IV of France married Otto's sister Gerberga in 939, and Otto's son Liudolf married Ida, daughter of Hermann I, Duke of Swabia, in 947. These unions tied the royal houses of West and East Francia and secured Liudolf's succession to the Duchy of Swabia, as Hermann had no sons. In 950, Liudolf became Duke of Swabia, and in 954, Otto's nephew Lothair of France became King of France.

In 944, Otto appointed Conrad the Red, a Salian Frank and nephew of former King Conrad I, as Duke of Lorraine, further integrating him into the royal family through his marriage to Otto's daughter Liutgarde in 947. Following the death of Otto's uncle Berthold, Duke of Bavaria, in 947, Otto finally satisfied his brother Henry's ambition by arranging his marriage to Judith, Duchess of Bavaria, daughter of Arnulf, Duke of Bavaria, and appointing Henry as the new Duke of Bavaria in 948. This arrangement brought peace between the brothers, as Henry abandoned his claims to the throne thereafter. Through these familial ties to the dukes, Otto significantly strengthened the sovereignty of the crown and the overall cohesion of the kingdom.

On 29 January 946, Eadgyth died suddenly at the age of 35 and was buried in Magdeburg Cathedral. The union had lasted sixteen years and produced two children. With Eadgyth's death, Otto began to make arrangements for his succession, intending to transfer sole rule to his son Liudolf. He gathered all leading figures of the kingdom and had them swear an oath of allegiance to Liudolf, recognizing him as the sole heir apparent.

3.3. Domestic and Church Policy

Otto's administrative reforms were deeply intertwined with his innovative use of the Church to bolster royal power and administrative efficiency, a policy that laid the groundwork for the Ottonian imperial church system.

3.3.1. Imperial Church System

Beginning in the late 940s, Otto systematically reorganized internal policies by utilizing the offices of the Catholic Church as tools of royal administration. Viewing himself as the protector of the Church due to his "divine right" to rule, he sought to establish a non-hereditary counter-balance to the fiercely independent and powerful secular princes. A key element of this administrative reorganization was the appointment of celibate clerics, primarily bishops and abbots, to secular offices, thereby circumventing the hereditary claims of the secular nobility.

Otto granted land and bestowed the title of Prince of the Empire (ReichsfürstPrince of the EmpireGerman) to these appointed bishops and abbots. This policy prevented hereditary claims, as upon their death, the offices and associated lands reverted to the crown, allowing Otto to reappoint loyal individuals. Clerical elections under this system became largely a formality, with the king filling the ranks of the episcopate with his own relatives and loyal chancery clerks, who also headed major German monasteries.

His own brother, Bruno the Great, who served as Otto's Chancellor since 940, was a prominent example of this blended royal-ecclesiastical service, being appointed Archbishop of Cologne and Duke of Lorraine in 953. Other significant religious officials in Otto's government included his illegitimate son, Archbishop William of Mainz, Archbishop Adaldag of Bremen, and Hadamar, the Abbot of Fulda. Otto generously endowed bishoprics and abbeys with land and royal prerogatives, such as the power to levy taxes and maintain an army. Over these Church lands, secular authorities had no power of taxation or legal jurisdiction, effectively elevating the Church above the various dukes and binding its clerics as personal vassals of the king. To further support the Church, Otto made tithing mandatory for all inhabitants of Germany.

Otto granted bishops and abbots the rank of count and the legal rights associated with it within their territories. Since Otto personally appointed all bishops and abbots, these reforms significantly strengthened his central authority, transforming the upper ranks of the German Church into an arm of the royal bureaucracy. He routinely promoted his personal court chaplains to bishoprics across the kingdom, rewarding their years of service within the royal court and their work in the royal chancery with ecclesiastical advancement.

3.4. Liudolf's Civil War

The civil war led by Otto's own son, Liudolf, represented a significant challenge to his authority and dynastic plans, ultimately impacting the succession.

3.4.1. Rebellion against Otto

Liudolf's estrangement from his father began with the perceived failure of his Italian campaign and Otto's subsequent marriage to Adelaide. On Christmas Day 951, Liudolf hosted a grand feast at Saalfeld, attended by many important figures, including Archbishop Frederick of Mainz, the Primate of Germany. Liudolf successfully recruited his brother-in-law, Conrad the Red, Duke of Lorraine, to his cause. Conrad felt betrayed by Otto's decision regarding Berengar II, as he had negotiated a peace agreement that Otto later undermined, especially with the increased empowerment of Henry. Both Liudolf and Conrad believed Otto was unduly influenced by his foreign-born wife and power-hungry brother, and they resolved to free the kingdom from their perceived domination.

In the winter of 952, Adelaide gave birth to a son, Henry, named after his uncle and grandfather. Rumors spread that Otto intended to name this child as his heir instead of Liudolf, a notion that many German nobles interpreted as Otto's final shift from a German-focused policy to an Italian-centered one. This rumor, coupled with the threat to Liudolf's succession rights, prompted many nobles into open rebellion. Liudolf and Conrad first led the nobles against Henry, Duke of Bavaria, in the spring of 953. Henry was unpopular with the Bavarians due to his Saxon heritage, and his vassals quickly rebelled against him.

News of the rebellion reached Otto at Ingelheim. To secure his position, he traveled to his stronghold at Mainz, the seat of Archbishop Frederick, who acted as a mediator. Although the exact terms are unrecorded, Otto soon left Mainz with a peace treaty favorable to the conspirators, likely confirming Liudolf as heir and approving Conrad's original agreement with Berengar II. However, these terms were incompatible with the desires of Adelaide and Henry.

Upon Otto's return to Saxony, Adelaide and Henry persuaded him to void the treaty. Convening the Imperial Diet at Fritzlar, Otto declared Liudolf and Conrad as outlaws in absentia. The king reasserted his ambition for dominion over Italy and the imperial title. He sent emissaries to the Duchy of Lorraine, stirring local nobles against Conrad, who was unpopular as a Salian Frank. The Lorrainers pledged support to Otto.

Otto's actions at the Diet provoked the people of Swabia and Franconia into rebellion. After initial defeats, Liudolf and Conrad retreated to their headquarters in Mainz. In July 953, Otto and his army, supported by Henry's army from Bavaria, laid siege to the city. After two months, Mainz had not fallen, and rebellions against Otto intensified in southern Germany. Faced with these challenges, Otto opened peace negotiations with Liudolf and Conrad. Bruno the Great, Otto's youngest brother and royal chancellor, accompanied them. As the newly appointed Archbishop of Cologne, Bruno was eager to end the civil war in Lorraine, which was part of his ecclesiastical territory. The rebels demanded ratification of the previous treaty, but Henry's provocations during the meeting caused negotiations to break down. Conrad and Liudolf left to continue the civil war. Angered, Otto stripped them of their duchies of Swabia and Lorraine, appointing his brother Bruno as the new Duke of Lorraine.

While on campaign, Henry appointed the Bavarian Count Palatine, Arnulf II, to govern his duchy. Arnulf II, son of Arnulf the Bad (whom Henry had displaced), sought revenge, deserting Henry and joining the rebellion. Otto and Henry marched south to regain Bavaria, but without local noble support, they failed and retreated to Saxony. By late 953, the civil war had engulfed Bavaria, Swabia, and Franconia, and even spread to Saxony, threatening to depose Otto and permanently end his claims as Charlemagne's successor.

3.4.2. Forcing an End to the Rebellion

In early 954, Margrave Hermann Billung, Otto's loyal vassal in Saxony, faced increased Slavic incursions from the east, as they exploited the German civil war. Meanwhile, the Magyars, led by Bulcsú, launched extensive raids into Southern Germany. Although Liudolf and Conrad had prepared defenses in their territories, the Hungarians devastated Bavaria and Franconia. On Palm Sunday 954, Liudolf hosted a feast at Worms and invited Hungarian chieftains, presenting them with gifts of gold and silver.

Otto's brother Henry quickly spread rumors that Conrad and Liudolf had invited the Hungarians into Germany to use them against Otto, causing public opinion in the rebellious duchies to turn against the rebels. With this shift and the death of his wife Liutgarde (Otto's only daughter), Conrad began peace negotiations with Otto, eventually joined by Liudolf and Archbishop Frederick. A truce was declared, and Otto called an Imperial Diet for 15 June 954 at Langenzenn. Before the assembly, Conrad and Frederick reconciled with Otto. However, at the Diet, tensions flared when Henry accused Liudolf of conspiring with the Hungarians. Despite pleas from Conrad and Frederick, an enraged Liudolf left the meeting, determined to continue the civil war.

Liudolf, with his lieutenant Arnulf II (the effective ruler of Bavaria), marched his army south towards Regensburg in Bavaria, closely pursued by Otto. The armies clashed at Nuremberg in a deadly but indecisive battle. Liudolf retreated to Regensburg, where Otto besieged him. Otto's army could not breach the city walls but caused starvation within two months. Liudolf sought peace, but Otto demanded unconditional surrender, which Liudolf refused. After Arnulf II was killed in ongoing fighting, Liudolf fled Bavaria for Swabia, with Otto's army in pursuit. They met at Illertissen near the Swabian-Bavarian border and opened negotiations. Liudolf and Otto agreed to a truce until an Imperial Diet could ratify the peace. The king forgave his son all transgressions, and Liudolf agreed to accept any punishment his father deemed appropriate.

Soon after this peace agreement, the ailing Archbishop Frederick died in October 954. With Liudolf's surrender, the rebellion was suppressed throughout Germany, except in Bavaria. Otto convened the Imperial Diet in December 954 at Arnstadt. Before the assembled nobles, Liudolf and Conrad declared their fealty to Otto and yielded control over all territories their armies still occupied. Otto did not restore their ducal titles but allowed them to retain their private estates. The Diet ratified Otto's actions:

- Liudolf was promised regency over Italy and command of an army to depose Berengar II.

- Conrad was promised military command against the Hungarians.

- Burchard III, son of former Swabian Duke Burchard II, was appointed Duke of Swabia (Liudolf's former duchy).

- Bruno remained as the new Duke of Lorraine (Conrad's former duchy).

- Henry was confirmed as Duke of Bavaria.

- Otto's oldest son, William, was appointed Archbishop of Mainz and Primate of Germany.

- Otto retained direct rule over the Duchy of Saxony and the territories of the former Duchy of Franconia.

These measures in December 954 finally ended the two-year civil war. Although Liudolf's rebellion temporarily weakened Otto's position, it ultimately strengthened him as the absolute ruler of Germany.

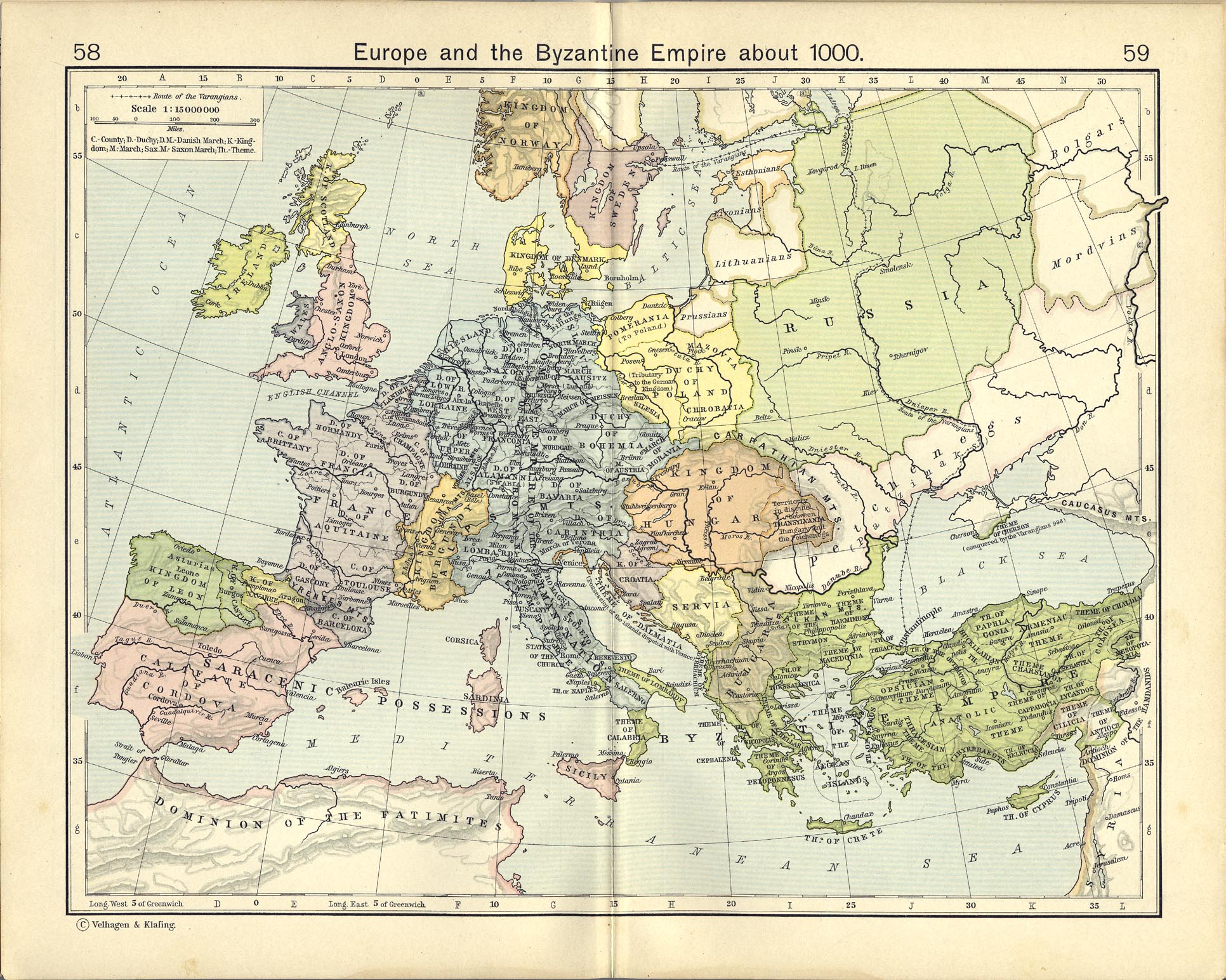

3.5. Foreign Relations

Otto I's foreign policy was characterized by a mix of diplomatic engagement, military intervention, and strategic alliances, shaping the geopolitical landscape of Europe.

3.5.1. Relations with the Frankish Kingdoms

The West Frankish kings had significantly lost royal power due to internal struggles with their aristocracy, yet they still asserted authority over the Duchy of Lorraine, a territory also claimed by East Francia. Otto's claim to Lorraine was supported by Louis IV's chief domestic rival, Hugh the Great. Louis IV's second attempt to rule Lorraine in 940 was based on his marriage to Gerberga of Saxony, Otto's sister and Gilbert's widow. Otto did not recognize Louis IV's claim and instead appointed his brother Henry as duke. In the following years, both sides vied for influence in Lorraine, but the duchy remained part of Otto's kingdom.

Despite their rivalry, Louis IV and Hugh were both connected to Otto's family through marriage. Otto intervened for peace in 942, announcing a formal reconciliation whereby Hugh would submit to Louis IV, and Louis IV would waive claims to Lorraine. After a brief peace, West Francia faced another crisis in 946 when Normans captured Louis IV and handed him to Hugh, who released the king only upon the surrender of the fortress of Laon. At his sister Gerberga's urging, Otto invaded France on Louis IV's behalf, but his armies were not strong enough to take Laon, Reims, or Paris. After three months, Otto lifted the siege without defeating Hugh but managed to depose Hugh of Vermandois as Archbishop of Reims, restoring Artald of Reims to office.

To resolve the control of the Archdiocese of Reims, Otto called a synod at Ingelheim on 7 June 948. Over 30 bishops attended, including all German archbishops, demonstrating Otto's strong position in both East and West Francia. The synod confirmed Otto's appointment of Artald as Archbishop of Reims, and Hugh was admonished to respect royal authority. However, Hugh did not fully accept Louis IV as king until 950, and their reconciliation was not complete until March 953.

Otto largely left West Frankish affairs to his son-in-law Conrad the Red and later Bruno the Great, along with his sisters Gerberga and Hedwige, who served as regents for their sons King Lothar and Duke Hugh. Otto received feudal commendation from several West Frankish magnates and, like his father, settled royal and episcopal succession disputes in the western kingdom. Bruno militarily intervened in West Francia in 958. However, this Ottonian hegemony from 940 to 965 was personal rather than institutional and quickly diminished after Hugh Capet's accession in 987.

3.5.2. Kingdom of Burgundy and Bohemia

Otto continued the peaceful relationship with the Kingdom of Burgundy (Arles) initiated by his father. King Rudolf II of Burgundy had married Bertha of Swabia, daughter of one of Henry's chief advisors, in 922. Burgundy, originally part of Middle Francia (Charlemagne's empire's central portion), became integral to Otto's sphere of influence. On 11 July 937, Rudolf II died, and Hugh of Provence, King of Italy and Rudolf II's main rival, claimed the Burgundian throne. Otto intervened in the succession, supporting Rudolf II's son, Conrad of Burgundy, who secured the throne. Burgundy remained formally independent but at peace with Germany during Otto's reign.

Boleslaus I, Duke of Bohemia, who ascended the Bohemian throne in 935, stopped paying tribute to the German Kingdom in 936 after Henry the Fowler's death, violating a peace treaty Henry had established with Boleslaus's brother and predecessor, Wenceslaus I. Boleslaus attacked a Saxon ally in northwest Bohemia in 936 and defeated two of Otto's armies from Thuringia and Merseburg. After this initial large-scale invasion, hostilities continued primarily through border raids until 950, when Otto besieged a castle owned by Boleslaus's son. Boleslaus signed a peace treaty, promising to resume tribute payments. Boleslaus subsequently became Otto's ally, and his Bohemian forces assisted the German army against the common Magyar threat at the Lech River in 955. Later, Boleslaus helped crush an uprising of two Slavic dukes, Stoigniew and Nako, in Mecklenburg, likely to secure the expansion of Bohemian estates eastward.

3.5.3. Byzantine Empire

During his early reign, Otto fostered close relations with Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, who ruled the Byzantine Empire from 913 to 959. East Francia and Byzantium exchanged several ambassadors. Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg, a medieval chronicler, recorded that "After this [Gilbert's defeat in 939], legates from the Greeks [Byzantines] twice brought gifts from their emperor to our king, both rulers being in a state of concord." It was during this period that Otto first attempted to forge a connection with the Eastern Empire through marriage negotiations.

3.5.4. Slavic Wars

As Otto was suppressing his brother's rebellion in 939, the Slavs on the Elbe River revolted against German rule, seeking to regain independence after being subdued by Otto's father in 928. Otto's lieutenant in east Saxony, Count Gero of Merseburg, was tasked with subjugating the pagan Polabian Slavs. According to Widukind, Gero invited about thirty Slavic chieftains to a banquet, where his soldiers massacred the unsuspecting guests after the feast. The Slavs retaliated with a massive army. Otto agreed to a brief truce with his rebellious brother Henry and moved to support Gero. After fierce fighting, their combined forces repelled the advancing Slavs, and Otto returned west to subdue his brother's rebellion.

In 941, Gero initiated another plot to subdue the Slavs. He recruited a captive Slav named Tugumir, a Hevelli chieftain, promising to support his claim to the Hevellian throne if Tugumir would later recognize Otto as his overlord. Tugumir agreed and returned to the Slavs. With few Slavic chieftains remaining after Gero's massacre, the Slavs quickly proclaimed Tugumir as their prince. Upon assuming the throne, Tugumir murdered his chief rival and declared loyalty to Otto, incorporating his territory into the German kingdom. Otto granted Tugumir the title of "duke" and allowed him to rule his people, subject to Otto's suzerainty, in the same manner as the German dukes. Following Gero and Tugumir's coup, the Slavic federation fragmented. With control of the key Hevelli stronghold of Brandenburg, Gero was able to attack and defeat the divided Slavic tribes. Otto and his successors extended their control into Eastern Europe through military colonization and the establishment of churches.

3.6. Hungarian Invasions

The threat posed by Hungarian raids was a persistent challenge to the German kingdom, culminating in Otto's decisive actions that secured the realm's safety.

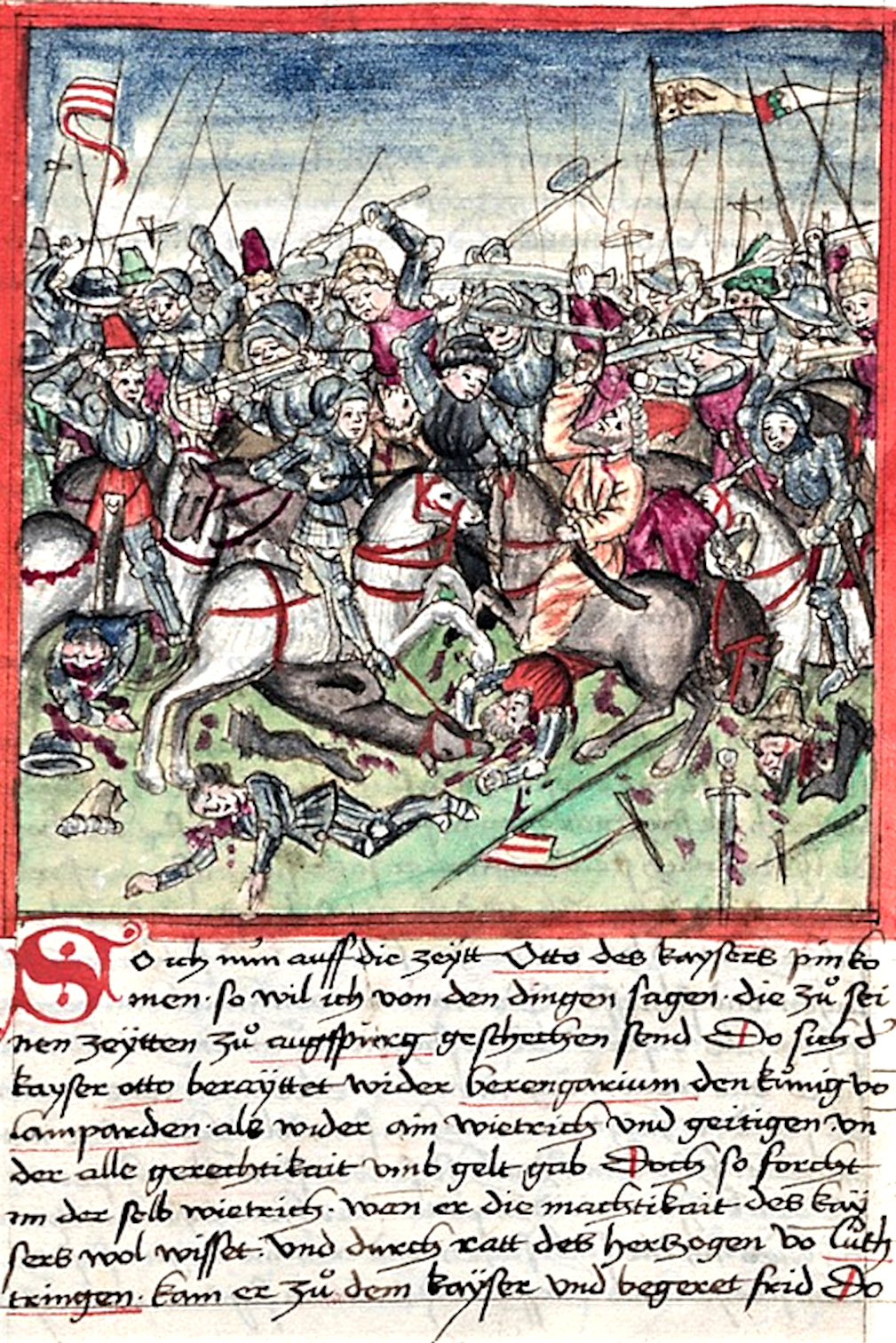

3.6.1. Battle of Lechfeld

The Hungarians (Magyars) invaded Otto's domain as part of the larger Hungarian invasions of Europe, ravaging much of Southern Germany during Liudolf's civil war. The Principality of Hungary to the southeast posed a constant threat. Taking advantage of the kingdom's internal conflict, the Hungarians invaded the Duchy of Bavaria in spring 954. Although Liudolf, Duke of Swabia, and Conrad, Duke of Lorraine, successfully prevented the Hungarians from invading their western territories, the invaders reached the Rhine River, sacking much of Bavaria and Franconia.

Encouraged by their successful raids, the Hungarians launched another invasion into Germany in spring 955. Otto's army, now unhindered by civil war, was ready to face the invasion. The Hungarians sent an ambassador seeking peace, but this proved to be a decoy. Otto's brother, Henry I, Duke of Bavaria, sent word that the Hungarians had crossed into his territory from the southeast. The main Hungarian army camped along the Lech River and besieged Augsburg. While Bishop Ulrich of Augsburg defended the city, Otto assembled his army and marched south.

Otto and his army fought the Hungarian force on 10 August 955 at the Battle of Lechfeld. Under Otto's command were Burchard III, Duke of Swabia, and Bohemian troops led by Duke Boleslaus I. Despite being outnumbered nearly two to one, Otto was determined to expel the Hungarians. According to Widukind of Corvey, Otto "pitched his camp in the territory of the city of Augsburg and joined there the forces of Henry I, Duke of Bavaria, who was himself lying mortally ill nearby, and by Duke Conrad with a large following of Franconian knights. Conrad's unexpected arrival encouraged the warriors so much that they wished to attack the enemy immediately."

The Hungarians crossed the river and immediately attacked the Bohemians, followed by the Swabians under Burchard. Confusing the defenders with a rain of arrows, they plundered the baggage train and took many captives. When Otto received word of the attack, he ordered Conrad to relieve his rear units with a counter-attack. Upon successful completion, Conrad returned to the main forces, and the King launched an immediate assault. Despite a volley of arrows, Otto's army smashed into the Hungarian lines and engaged them in hand-to-hand combat, denying the traditionally nomadic warriors the space for their preferred shoot-and-run tactics. The Hungarians suffered heavy losses and were forced to retreat in disorder. Scattered parts of the Hungarian army were subsequently attacked by nearby villages and castles, and a second Bohemian force under Duke Boleslaus I intercepted and defeated them. The Hungarian leaders, Lehel, Bulcsú, and Súr, were executed in Regensburg.

According to Widukind of Corvey, Otto was proclaimed Father of the Fatherland and Emperor at the subsequent victory celebration. While the battle was not a crushing defeat that allowed Otto to pursue the fleeing army into Hungarian lands, it effectively ended nearly 100 years of Hungarian invasions into Western Europe.

While Otto was fighting the Hungarians in Southern Germany, the Obotrite Slavs in the north were in insurrection. Count Wichmann the Younger, still an opponent of Otto due to the King's refusal to grant him the title of Margrave in 936, marauded through the lands of the Obotrites in the Billung March, inciting a revolt among the followers of Slavic Prince Nako. The Obotrites invaded Saxony in autumn 955, killing men of arms-bearing age and enslaving women and children. In the aftermath of the Battle of Lechfeld, Otto rushed north and pressed deep into their territory. A Slav embassy offered to pay annual tribute for self-government under German overlordship, but Otto refused. The two sides met on 16 October at the Battle of Recknitz. Otto's forces achieved a decisive victory, and hundreds of captured Slavs were executed after the battle.

Celebrations for Otto's victories over the pagan Hungarians and Slavs were held in churches across the kingdom, with bishops attributing the victories to divine intervention and as proof of Otto's "divine right" to rule. The battles of Lechfeld and Recknitz marked a turning point in Otto's reign. These victories solidified his hold on power over Germany, with the duchies firmly under royal authority. From 955 onward, Otto would not face another rebellion against his rule, allowing him to further consolidate his position throughout Central Europe.

Otto's son-in-law, Conrad, the former Duke of Lorraine, was killed in the Battle of Lechfeld, and the king's brother, Henry I, Duke of Bavaria, was mortally wounded, dying on 1 November of that year. With Henry's death, Otto appointed his four-year-old nephew, Henry II, to succeed his father as duke, with his mother, Judith of Bavaria, as regent. Otto appointed Liudolf in 956 as the commander of an expedition against King Berengar II of Italy, but Liudolf soon died of fever on 6 September 957 and was buried at St. Alban's Abbey near Mainz by Archbishop William. The deaths of Henry, Liudolf, and Conrad removed three prominent members of his royal family, including his heir apparent. Additionally, his first two sons from his marriage to Adelaide of Italy, Henry and Bruno, had both died in early childhood by 957. Otto's third son by Adelaide, the two-year-old Otto, became the kingdom's new heir apparent.

4. Conquest of Italy and Imperial Coronation

Otto I's campaigns in Italy, his assumption of the Italian crown, and his ultimate coronation as Holy Roman Emperor were pivotal moments that redefined his reign and the future of medieval Europe.

4.1. Disputed Italian Throne

Upon the death of Emperor Charles the Fat in 888, Charlemagne's empire was fragmented into several territories, including East Francia, West Francia, the kingdoms of Lower and Upper Burgundy, and the Kingdom of Italy. Although the Pope in Rome continued to invest the kings of Italy as "emperors" to rule Charlemagne's empire, these "Italian emperors" never exercised significant authority north of the Alps. When Berengar I of Italy was assassinated in 924, the last nominal heir to Charlemagne's imperial title died, leaving the emperorship unclaimed for nearly four decades.

The political fragmentation of Italy led to intense competition for the royal title. King Rudolf II of Upper Burgundy and Hugh, Count of Provence (the effective ruler of Lower Burgundy), vied for dominion over Italy. In 926, Hugh's armies defeated Rudolf, allowing Hugh to establish de facto control over the Italian Peninsula and crown himself King of Italy. His son, Lothair, was elevated to co-ruler in 931. Hugh and Rudolf II eventually concluded a peace treaty in 933, and four years later, Lothair was betrothed to Rudolf's infant daughter, Adelaide.

In 940, Berengar II, Margrave of Ivrea and a grandson of former King Berengar I, led a revolt of Italian nobles against his uncle Hugh. Forewarned by Lothair, Hugh exiled Berengar II from Italy, who fled to Otto's court in 941. In 945, Berengar II returned and, with the support of the Italian nobility, defeated Hugh. Hugh abdicated in favor of his son and retired to Provence, while Berengar II made terms with Lothair, establishing himself as the decisive power behind the throne. Lothair married the sixteen-year-old Adelaide in 947 and became nominal king when Hugh died on 10 April 948, but Berengar II continued to wield real power as a mayor of the palace or viceroy.

4.2. Strategic Marriage to Adelaide

Lothair's brief "reign" ended with his death on 22 November 950. Berengar II was crowned king on 15 December, with his son Adalbert of Italy as co-ruler. Failing to receive widespread support, Berengar II attempted to legitimize his reign by forcing Adelaide, who was the daughter, daughter-in-law, and widow of the last three Italian kings, into marriage with Adalbert. Adelaide fiercely refused and was imprisoned by Berengar II at Garda Lake. With the help of Count Adalbert Atto of Canossa, she managed to escape and, besieged by Berengar II in Canossa, sent an emissary across the Alps seeking Otto's protection and marriage. A marriage to Adelaide would significantly strengthen Otto's claim to the Italian throne and ultimately the emperorship. Knowing of her great intelligence and immense wealth, Otto accepted Adelaide's marriage proposal and prepared for an expedition into Italy.

4.3. First Italian Expedition

In the early summer of 951, before his father marched across the Alps, Otto's son, Liudolf, Duke of Swabia, invaded Lombardy in Northern Italy. The exact reasons for Liudolf's actions are unclear; historians suggest he may have sought to aid Adelaide, a distant relative of his wife Ida, or aimed to strengthen his position within the royal family. He was also competing with his uncle, Duke Henry I of Bavaria, in both German and Northern Italian affairs. While Liudolf prepared his expedition, Henry influenced Italian aristocrats not to join Liudolf's campaign. When Liudolf arrived in Lombardy, he found no support and struggled to sustain his troops. His army was on the verge of destruction until Otto's forces crossed the Alps. The king reluctantly incorporated Liudolf's forces into his command, angered by his son's independent actions.

Otto and Liudolf's troops arrived in northern Italy in September 951 without opposition from Berengar II. As they descended into the Po River valley, Italian nobles and clergy withdrew their support for Berengar and aided Otto's advancing army. Recognizing his weakened position, Berengar II fled his capital in Pavia. When Otto arrived at Pavia on 23 September 951, the city willingly opened its gates to the German king, who was crowned King of the Lombards and assumed the titles of Rex Italicorum and Rex Langobardorum from 10 October onward. Like Charlemagne before him, Otto was now concurrently King of Germany and King of Italy. Otto sent a message to his brother Henry in Bavaria to escort his bride from Canossa to Pavia, where the two were married.

Soon after his father's marriage in Pavia, Liudolf left Italy and returned to Swabia. Archbishop Frederick of Mainz, the Primate of Germany and Otto's long-time domestic rival, also returned to Germany with Liudolf. Disturbances in northern Germany forced Otto to return with the majority of his army across the Alps in 952. Otto left a small portion of his army in Italy and appointed his son-in-law, Conrad the Red, Duke of Lorraine, as his regent, tasking him with subduing Berengar II.

4.4. Diplomacy and Feudal Agreements

In a weak military position with limited troops, Otto's regent in Italy, Conrad, pursued a diplomatic solution, opening peace negotiations with Berengar II. Conrad recognized that a military confrontation would be costly for Germany, both in manpower and resources, especially as the kingdom faced invasions from the Danes in the north and Slavs and Hungarians in the east. He believed a client state relationship with Italy would best serve Germany's interests. He offered a peace treaty whereby Berengar II would remain King of Italy on the condition that he recognized Otto as his overlord. Berengar II agreed, and they traveled north to meet Otto and finalize the agreement.

Conrad's treaty was met with disdain by Adelaide and Henry. Adelaide, though Burgundian by birth, was raised as an Italian. Her father, Rudolf II of Burgundy, had briefly been King of Italy, and she herself had been queen until her husband Lothair II's death, after which Berengar II imprisoned her for refusing to marry his son. Henry had his own reasons for disapproval: as Duke of Bavaria, he controlled territory on the northern German-Italian border and hoped to expand his fiefdom by incorporating territory south of the Alps if Berengar II were deposed. Conrad and Henry were already on poor terms, and the proposed treaty further strained their relationship. Adelaide and Henry conspired to persuade Otto to reject Conrad's treaty.

Conrad and Berengar II arrived at Magdeburg to meet Otto but were made to wait three days before an audience was granted, a humiliating offense for Otto's appointed regent. Although Adelaide and Henry urged immediate rejection of the treaty, Otto referred the issue to an Imperial Diet for further debate. Appearing before the Diet in August 952 in Augsburg, Berengar II and his son Adalbert were forced to swear fealty to Otto as his vassals. In return, Otto granted Berengar II Italy as his fiefdom and restored the title "King of Italy" to him. The Italian king, however, had to pay an enormous annual tribute and was required to cede the Duchy of Friuli south of the Alps. Otto reorganized this area into the March of Verona and placed it under Henry's control as a reward for his loyalty, thereby making the Duchy of Bavaria the most powerful domain in Germany.

4.5. Second Italian Expedition and Imperial Coronation

Liudolf's death in autumn 957 deprived Otto of both an heir and a commander for his expedition against King Berengar II of Italy. Berengar II had always been a rebellious subordinate. With the deaths of Liudolf and Henry I, Duke of Bavaria, and Otto campaigning in northern Germany, Berengar II attacked the March of Verona in 958 (which Otto had stripped from his control under the 952 treaty) and besieged Count Adalbert Atto of Canossa there. Berengar II's forces also attacked the Papal States and the city of Rome under Pope John XII. In autumn 960, with Italy in political turmoil, the Pope sent word to Otto seeking aid against Berengar II. Several other influential Italian leaders arrived at Otto's court with similar appeals, including the Archbishop of Milan, the bishops of Como and Novara, and Margrave Otbert of Milan.

After the Pope agreed to crown him as Emperor, Otto assembled his army to march upon Italy. In preparation for his second Italian campaign and the imperial coronation, Otto planned his kingdom's future. At the Imperial Diet at Worms in May 961, Otto named his six-year-old son Otto II as heir apparent and co-ruler, and had him crowned at Aachen Cathedral on 26 May 961. Otto II was anointed by Archbishops Bruno I of Cologne, William of Mainz, and Henry I of Trier. The King instituted a separate chancery to issue diplomas in his heir's name and appointed his brother Bruno and illegitimate son William as Otto II's co-regents in Germany.

Otto's army descended into northern Italy in August 961 through the Brenner Pass at Trento. The German king moved towards Pavia, the former Lombard capital of Italy, where he celebrated Christmas and assumed the title King of Italy for himself. Berengar II's armies retreated to their strongholds to avoid battle with Otto, allowing him to advance southward unopposed. Otto reached Rome on 31 January 962; three days later, he was crowned Emperor by Pope John XII at Old St. Peter's Basilica. The Pope also anointed Otto's wife, Adelaide of Italy, who had accompanied Otto on his Italian campaign, as empress. With Otto's coronation as emperor, the Kingdom of Germany and the Kingdom of Italy were unified into a common realm, later called the Holy Roman Empire.

4.6. Papal Politics

On 12 February 962, Emperor Otto I and Pope John XII called a synod in Rome to formalize their relationship. At the synod, Pope John XII approved Otto's long-desired Archdiocese of Magdeburg. The Emperor had planned the establishment of the archdiocese to commemorate his victory at the Battle of Lechfeld over the Hungarians and to further convert the local Slavs to Christianity. The Pope named the former royal monastery of St. Maurice as the provisional center of the new archdiocese and called upon the German archbishops for support.

The following day, Otto and John XII ratified the Diploma Ottonianum, confirming John XII as the spiritual head of the Church and Otto as its secular protector. In the Diploma, Otto acknowledged the earlier Donation of Pepin of 754 between Pepin the Short, King of the Franks, and Pope Stephen II. Otto recognized John XII's secular control over the Papal States and expanded the Pope's domain by including the Exarchate of Ravenna, the Duchy of Spoleto, the Duchy of Benevento, and several smaller possessions. However, Otto was not obligated to provide military aid if these territories were conquered, and despite this confirmed claim, Otto never ceded real control over those additional territories. The Diploma granted the clergy and people of Rome the exclusive right to elect the pontiff. The pope-elect was required to issue an oath of allegiance to the emperor before his confirmation as pope, an agreement based on feudal law that effectively gave the emperor power over the pope.

With the Diploma signed, the new Emperor marched against Berengar II to reconquer Italy. Being besieged at San Leo, Berengar II surrendered in 963. Upon the successful completion of Otto's campaign, John XII began to fear the Emperor's rising power in Italy and opened negotiations with Berengar II's son, Adalbert of Italy, to depose Otto. The Pope also sent envoys to the Hungarians and the Byzantine Empire to join him and Adalbert in an alliance against the Emperor. Otto discovered the Pope's plot and, after defeating and imprisoning Berengar II, marched on Rome. John XII fled from Rome, and Otto, upon his arrival, summoned a council and deposed John XII as Pope, appointing Leo VIII as his successor.

4.7. Response to Roman Election of Pope Benedict V

Otto released most of his army to return to Germany by the end of 963, confident his rule in Italy and within Rome was secure. The Roman populace, however, considered Leo VIII, a layman with no prior ecclesiastical training, unacceptable as Pope. In February 964, the Roman people forced Leo VIII to flee the city. In his absence, Leo VIII was deposed, and John XII was restored to the chair of St. Peter. When John XII died suddenly in May 964, the Romans elected Pope Benedict V as his successor. Upon hearing of the Romans' actions, Otto mobilized new troops and marched on Rome. After laying siege to the city in June 964, Otto forced the Romans to accept his appointee Leo VIII as Pope and exiled Benedict V.

4.8. Third Italian Expedition

Otto returned to Germany in January 965, believing his affairs in Italy had been settled. On 20 May 965, the Emperor's long-serving lieutenant on the eastern front, Margrave Gero, died, leaving a vast march stretching from the Billung March in the north to the Duchy of Bohemia in the south. Otto divided this territory into five separate smaller marches, each ruled by a margrave: the Northern March under Dietrich of Haldensleben, the Eastern March under Odo I, the March of Meissen under Wigbert, the March of Merseburg under Günther, and the March of Zeitz under Wigger I.

Peace in Italy, however, would not last long. Adalbert, the son of the deposed King Berengar II of Italy, rebelled against Otto's rule over the Kingdom of Italy. Otto dispatched Burchard III of Swabia, one of his closest advisors, to crush the rebellion. Burchard III met Adalbert at the Battle of the Po on 25 June 965, defeating the rebels and restoring Italy to Ottonian control. Pope Leo VIII died on 1 March 965, leaving the chair of St. Peter vacant. The Church elected, with Otto's approval, John XIII as new Pope in October 965. John XIII's arrogant behavior and foreign backing soon made him disliked among the local population. In December of the same year, he was taken into custody by the Roman people but was able to escape a few weeks later. Following the Pope's request for help, the Emperor prepared his army for a third expedition into Italy.

In August 966 at Worms, Otto announced his arrangements for the government of Germany in his absence. Otto's illegitimate son, Archbishop William of Mainz, would serve as his regent over all of Germany, while Otto's trusted lieutenant, Margrave Hermann Billung, would be his personal administrator over the Duchy of Saxony. With preparations completed, Otto left his heir in William's custody and led his army into northern Italy via Strasbourg and Chur.

4.9. Reign from Rome

Upon Otto's arrival in Italy, John XIII was restored to his papal throne in mid-November 966 without opposition from the people. Otto captured the twelve leaders of the rebel militia, which had deposed and imprisoned the Pope, and had them hanged. Taking up permanent residence in Rome, the Emperor traveled, accompanied by the Pope, to Ravenna to celebrate Easter in 967. A subsequent synod confirmed Magdeburg's disputed status as a new archdiocese with equal rights to the established German archdioceses.

With his matters arranged in northern Italy, the Emperor continued to expand his realm to the south. Since February 967, the Prince of Benevento, Lombard Pandulf Ironhead, had accepted Otto as his overlord and received Spoleto and Camerino as fiefdoms. This decision caused conflict with the Byzantine Empire, which claimed sovereignty over the principalities of southern Italy. The Eastern Empire also objected to Otto's use of the title Emperor, believing only the Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas was the true successor of the ancient Roman Empire.

The Byzantines opened peace talks with Otto, despite his expansive policy in their sphere of influence. Otto desired both an imperial princess as a bride for his son and successor, Otto II, as well as the legitimacy and prestige of a connection between the Ottonian dynasty in the West and the Macedonian dynasty in the East. To further his dynastic plans and in preparation for his son's marriage, Otto returned to Rome in the winter of 967, where he had Otto II crowned co-Emperor by Pope John XIII on Christmas Day 967. Although Otto II was now nominal co-ruler, he exercised no real authority until the death of his father.

In the following years, both empires sought to strengthen their influence in southern Italy with several campaigns. In 969, John I Tzimiskes assassinated and succeeded Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros in a military revolt. Finally recognizing Otto's imperial title, the new Eastern Emperor sent his niece Theophanu to Rome in 972, and she married Otto II on 14 April 972. As part of this rapprochement, the conflict over southern Italy was finally resolved: the Byzantine Empire accepted Otto's dominion over the principalities of Capua, Benevento, and Salerno; in return, the German Emperor retreated from the Byzantine possessions in Apulia and Calabria.

5. Culture

Otto I's reign fostered a significant cultural revival, often referred to as the Ottonian Renaissance, characterized by the patronage of arts, architecture, and learning.

5.1. Ottonian Renaissance

A limited renaissance of the arts and architecture in the second half of the 10th century flourished under the court patronage of Otto and his immediate successors. The Ottonian Renaissance manifested in the revival of several cathedral schools, such as that of Bruno I, Archbishop of Cologne, and in the production of illuminated manuscripts, the major art form of the age. These manuscripts were produced from a handful of elite scriptoria, including the one at Quedlinburg Abbey, which Otto himself founded in 936. Extant manuscripts from this era include the Diploma Ottonianum, the Marriage Charter of Empress Theophanu, and the Gero Codex, an evangeliary drawn up around 969 for Archbishop Gero.

The Imperial abbeys and courts became vibrant centers of religious and spiritual life. Prestigious convents like Gandersheim and Quedlinburg were notably led by women of the royal family. A prominent figure of this period was Hrotsvitha, considered the first female writer from the Germanosphere, the first female historian, the first person since the Fall of the Western Roman Empire to write dramas in the Latin West, and the first German female poet. She was raised in Otto's court, where she was exposed to classical authors. As an adult, Hrotsvitha became well-versed in the legal system, the history of the Ottonian dynasty, and their line of succession. She was also the first Northern European to write about Islam and the Islamic empire. After entering a royal convent, she wrote plays that blended Roman comedy with tales of early Christian martyrs.

6. Final Years and Death

Otto I's final years saw him consolidate his imperial authority and secure his dynastic succession before his death in 973.

6.1. Return to Germany and Final Year

With his son's wedding to Theophanu completed and peace with the Byzantine Empire concluded, Otto led the imperial family back to Germany in August 972. In the spring of 973, the Emperor visited Saxony and celebrated Palm Sunday in Magdeburg. At the same ceremony the previous year, Margrave Hermann Billung, Otto's trusted lieutenant and personal administrator over Saxony during his years in Italy, had been received like a king by Archbishop Adalbert of Magdeburg, a gesture that may have been a subtle protest against the Emperor's prolonged absence from Germany.

Celebrating Easter with a great assembly in Quedlinburg, Emperor Otto was at the height of his power, recognized as the most influential man in Europe. According to Thietmar of Merseburg, Otto received "the dukes Miesco [of Poland] and Boleslav [of Bohemia], and legates from the Greeks [Byzantium], the Beneventans [Rome], Magyars, Bulgars, Danes and Slavs." Ambassadors from England and Al-Andalus also arrived later that same year, further underscoring his international standing.

To mark the Rogation Days, Otto traveled to his palace at Memleben, the same place where his father had died 37 years earlier. While there, Otto became seriously ill with a fever and, after receiving his last sacraments, died on 7 May 973 at the age of 60.

6.2. Death

The transition of power to his seventeen-year-old son, Otto II, was seamless. On 8 May 973, the lords of the Empire confirmed Otto II as their new ruler. Otto II arranged a magnificent thirty-day funeral for his father, who was buried beside his first wife, Eadgyth, in Magdeburg Cathedral.

7. Family and Children

Otto I's family life was deeply intertwined with his political strategies, as he used dynastic ties to consolidate power and ensure succession.

7.1. Wives and Children

Although never emperor himself, Otto's father Henry the Fowler is considered the founder of the Ottonian dynasty. Otto I was Henry I's son, the father of Otto II, grandfather of Otto III, and great-uncle to Henry II. The Ottonians would rule Germany (later the Holy Roman Empire) for over a century, from 919 until 1024.

Otto had two wives and at least seven children, one of whom was illegitimate:

- With an unidentified Slavic woman:

- William (929 - 2 March 968) - Archbishop of Mainz from 17 December 954 until his death.

- With Eadgyth of England, daughter of King Edward the Elder:

- Liudolf (930 - 6 September 957) - Duke of Swabia from 950 to 954, Otto's expected successor from 947 until his death.

- Liutgarde (932-953) - married Conrad the Red, Duke of Lorraine, in 947. Their great-grandson was Emperor Conrad II, who founded the Salian dynasty.

- With Adelaide of Italy, daughter of King Rudolf II of Burgundy:

- Henry (952-954) - died in early childhood.

- Bruno (probably 954-957) - died in early childhood.

- Matilda (954-999) - Abbess of Quedlinburg from 966 until her death.

- Otto II (955 - 7 December 983) - Holy Roman Emperor from 973 until his death.

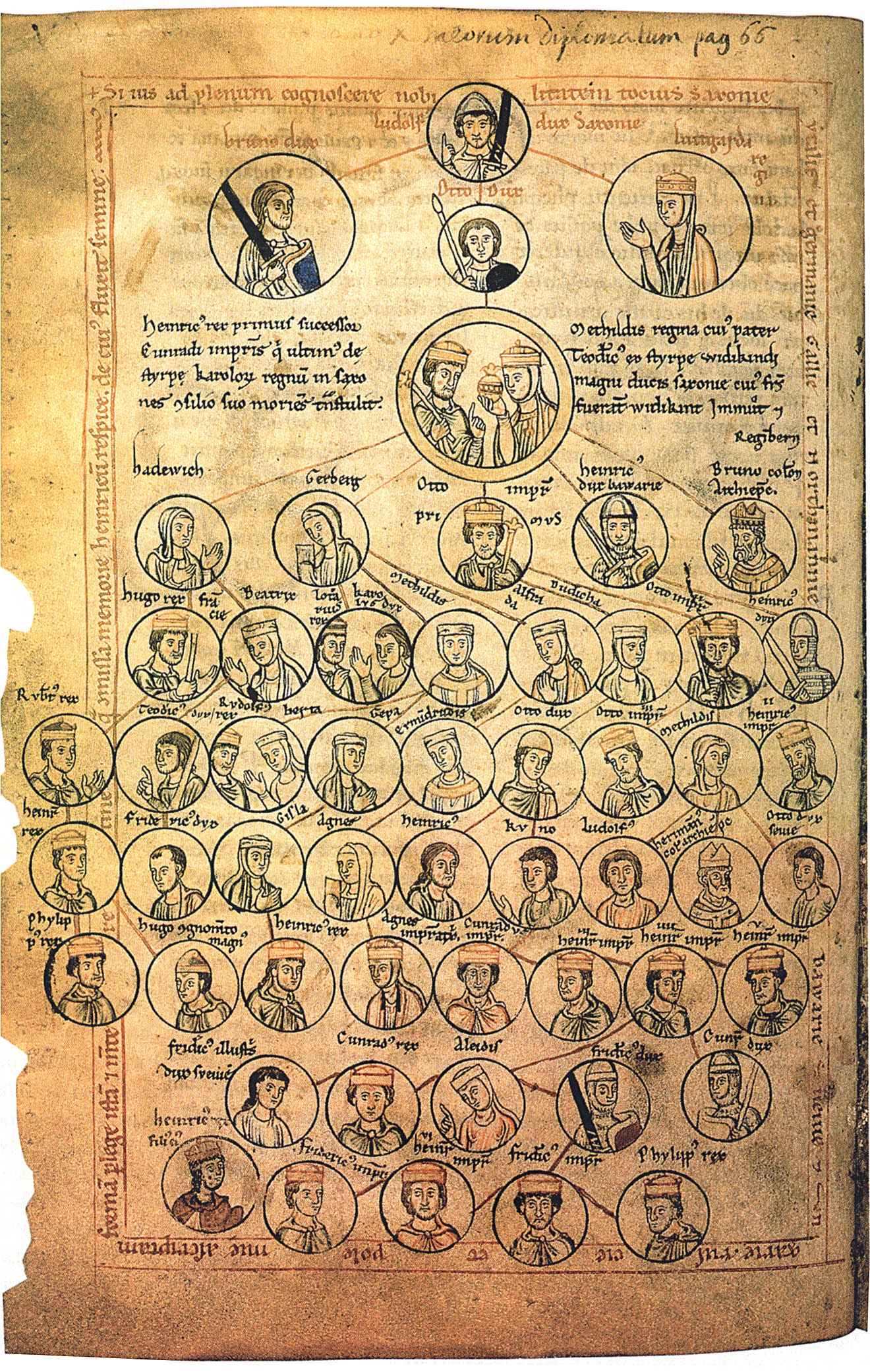

7.2. Ancestry

Otto I's lineage traces back through his father, Henry I, to the broader Ottonian dynasty, establishing his deep roots within the Saxon nobility that would come to dominate the German kingdom. The Ottonian dynasty, also known as the Liudolfing dynasty, was founded by Liudolf, Duke of Saxony, Otto I's great-grandfather. This lineage provided Otto with a strong claim to power in Saxony and a foundation for his broader ambitions in Germany and Italy.

8. Legacy and Evaluation

Otto I's reign left an indelible mark on European history, shaping the political and cultural landscape of the Middle Ages.

8.1. Modern World

Otto I's enduring legacy is recognized in the modern world through various commemorations and exhibitions. He was chosen as the main motif for a high-value commemorative coin, the 100 EUR Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire commemorative coin, issued in 2008 by the Austrian Mint. The coin's obverse features the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, while the reverse depicts Emperor Otto I with Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome in the background, where his coronation took place.

Furthermore, his life and influence on medieval European history have been documented and celebrated in major exhibitions, including three notable events held in Magdeburg in 2001, 2006, and 2012, highlighting his continuing historical significance.

8.2. Historical Evaluation

Historians have consistently depicted Otto I as a highly successful ruler and a great military commander, particularly at the strategic level. His victory at the Battle of Lechfeld against the Magyars, which ended nearly a century of Hungarian invasions into Western Europe, cemented his reputation as a "savior of Christendom" and secured his hold over the German kingdom. This victory, alongside his campaigns against the Slavs, marked a turning point, firmly establishing royal authority over the duchies and eliminating internal rebellions after 955.

Modern historiography, while acknowledging his strong character and numerous fruitful initiatives, also explores his capabilities as a consensus builder. This perspective aligns with a greater recognition of the nature of consensus politics in medieval Europe and the diverse roles played by other actors during his time.

Historian David Bachrach emphasizes the crucial role of the bureaucracy and administrative apparatus that the Ottonians inherited from the Carolingians and ultimately from the Ancient Romans, which they significantly developed. Bachrach states, "It was the success of the Ottonians in molding the raw materials bequeathed to them into a formidable military machine that made possible the establishment of Germany as the preeminent kingdom in Europe from the tenth through the mid-thirteenth century." He particularly highlights the achievements of the first two Ottonian rulers, Henry I and Otto the Great, in creating this powerful state. Their reigns also marked the beginning of new, vigorous literary traditions. Otto's patronage, and that of his immediate successors, facilitated the so-called "Ottonian Renaissance" of arts and architecture, contributing to a flourishing of culture and learning. As one of the most notable Holy Roman Emperors, Otto's influence is also considerably reflected in artistic depictions of the era.