1. Overview

Otto Karl Wilhelm Neurath (Otto NeurathGerman; 10 December 1882 - 22 December 1945) was an Austrian-born philosopher of science, sociologist, and political economist. A leading figure of the Vienna Circle before his exile in 1934, Neurath was a proponent of logical positivism and a key advocate for the Unity of Science movement. He is also recognized for inventing the ISOTYPE method of pictorial statistics and for his innovative approaches to museum practice, aiming to make complex information accessible for social and scientific progress. He was the only member of the Vienna Circle with a strong interest in the social sciences.

2. Early Life and Education

Neurath was born in Vienna, Austria, on 10 December 1882. His father, Wilhelm Neurath (1840-1901), was a prominent Jewish political economist and social reformer of his time. His mother was Protestant, and Otto Neurath himself also adopted the Protestant faith. Helene Migerka was his cousin.

He pursued academic studies in mathematics and physics at the University of Vienna, formally enrolling for two semesters in 1902-1903. In 1906, he earned his PhD from the Department of Political Science and Statistics at the University of Berlin. His doctoral thesis was titled Zur Anschauung der Antike über Handel, Gewerbe und Landwirtschaft (On the Conceptions in Antiquity of Trade, Commerce and Agriculture).

Neurath married Anna Schapire in 1907. She died in 1911 while giving birth to their son, Paul Neurath, who later became a sociologist. Following Anna's death, Neurath married Olga Hahn, a close friend who was a mathematician and philosopher. Due to Olga's blindness and the outbreak of World War I, their son Paul was sent to a children's home outside Vienna, where Neurath's mother lived. Paul returned to live with his parents at the age of nine.

3. Career in Vienna

Otto Neurath's career in Vienna was marked by diverse academic and professional activities, his pivotal role in the Vienna Circle, and his groundbreaking work in visual communication through ISOTYPE.

3.1. Academic and Professional Activities

Before the outbreak of World War I, Neurath taught political economy at the New Vienna Commercial Academy in Vienna. During the war, he became a leading expert in war economics, directing the Department of War Economy in the War Ministry. In 1917, he completed his habilitation thesis, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre und ihre Bedeutung für die Zukunft (War Economics and Their Importance for the Future), at Heidelberg University.

In 1918, Neurath was appointed director of the Deutsches Kriegswirtschaftsmuseum (German Museum of War Economy, later renamed "Deutsches Wirtschaftsmuseum") in Leipzig. Here, he collaborated with Wolfgang Schumann, who was known from the Dürerbund for which Neurath had written many articles, and Hermann Kranold to develop the Programm Kranold-Neurath-Schumann, a plan for socialization in Saxony. Between 1918 and 1919, Neurath joined the German Social Democratic Party and managed an office for central economic planning in Munich. Following the defeat of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, he was imprisoned on charges of treason but was released and returned to Austria after intervention from the Austrian government. While incarcerated, he wrote Anti-Spengler, a critical response to Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West.

In Red Vienna, Neurath joined the Social Democrats and became the secretary of the Austrian Association for Settlements and Small Gardens (Verband für Siedlungs-und Kleingartenwesen), an organization dedicated to providing housing and garden plots through self-help initiatives. In 1923, he founded the Siedlungsmuseum, a new museum focused on housing and city planning. In 1925, he renamed it the Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum in Wien (Museum of Society and Economy in Vienna) and established an associated organization. This association included the Vienna city administration, trade unions, the Chamber of Workers, and the Bank of Workers, with then-mayor Karl Seitz serving as its first proponent and Julius Tandler, city councillor for welfare and health, on its initial board. The museum's exhibitions were housed in city administration buildings, notably the People's Hall at the Vienna City Hall. This museum can also be found at [http://www.wirtschaftsmuseum.at/oegwm.htm Austrian Museum for Social and Economic Affairs]. Neurath also contributed to the Social Democratic magazine Der Kampf.

3.2. Vienna Circle and Logical Positivism

During the 1920s, Otto Neurath emerged as an ardent logical positivist and was a central figure in the Vienna Circle, co-authoring its influential manifesto. He was a driving force behind the Unity of Science movement, which sought to unify all branches of knowledge under a single scientific framework. This ambition culminated in the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, a project he spearheaded alongside collaborators like Rudolf Carnap, Bertrand Russell, Niels Bohr, John Dewey, and Charles W. Morris. Although the encyclopedia aimed to systematically formulate all academic disciplines, it ultimately published only two volumes. Neurath's involvement in the Unity of Science movement reflected his belief that social sciences could achieve the predictive accuracy of physics and chemistry by adhering to causal principles.

Neurath became Secretary of the Ernst Mach Society in 1927. As a member of the "left wing" of the Vienna Circle, he rejected both metaphysics and epistemology, viewing Marxism as a paradigm of scientific thought and science itself as a tool for social change. He was also a strong proponent of Esperanto, attending the 1924 World Esperanto Congress in Vienna, where he first met Rudolf Carnap.

3.3. ISOTYPE and Visual Communication

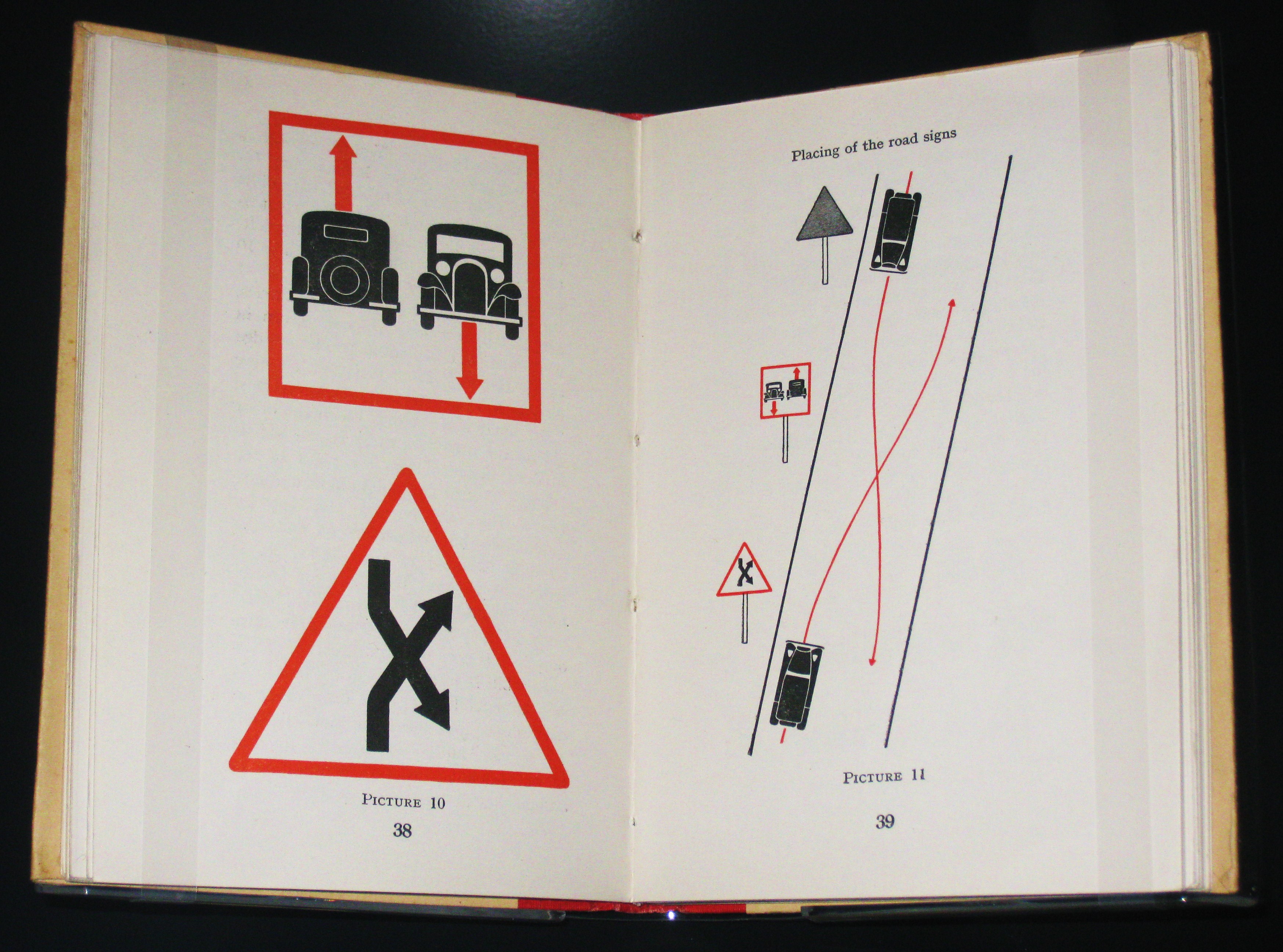

To make the Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum understandable to the diverse, polyglot population of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Neurath focused on graphic design and visual education. He famously coined the phrase "Words divide, pictures unite" (Worte trennen, Bilder verbindenGerman), which was displayed in his office. In the late 1920s, with the assistance of graphic designer Rudolf Modley and in collaboration with illustrator Gerd Arntz and Marie Reidemeister (whom he would later marry), Neurath developed innovative methods for representing quantitative information using easily interpretable icons.

This pioneering system, a forerunner of modern infographics, was initially called the Vienna Method of Pictorial Statistics. As its scope expanded beyond Vienna's social and economic data, Neurath renamed it "Isotype" - an acronym for "International System of Typographic Picture Education." The symbols designed by Neurath and his team aimed to help illiterate or non-specialist individuals understand social changes and inequalities by visually representing demographic and social statistics. This work significantly influenced cartography and graphic design. Neurath actively promoted these communication tools at international conventions for city planners.

During the 1930s, he also promoted Isotype as an International Picture Language, linking it to both the adult education movement and the internationalist enthusiasm for new artificial languages like Esperanto. However, he consistently emphasized that Isotype was not intended as a stand-alone language and had limitations in what it could convey. Marie Reidemeister's role in transforming data and statistics into visual forms, known as the "transformer," was particularly influential in museum and exhibition practices.

4. Economic and Social Thought

Neurath's economic and social thought was deeply influenced by his experiences during wartime and his commitment to socialist ideals, leading him to advocate for radical economic reforms. He was a notable proponent of "in-kind" economic accounting, arguing for its superiority over traditional monetary accounting. In the 1920s, he championed Vollsozialisierung (complete socialization), a more radical approach to economic transformation than that favored by mainstream Social-Democratic parties in Germany and Austria. He engaged in debates on these matters with leading Social Democratic theoreticians, such as Karl Kautsky, who maintained that money was essential in a socialist economy.

Neurath's conviction in the feasibility of economic planning without money stemmed from his observations as a government economist during World War I. He noted that "As a result of the war, in-kind calculus was applied more often and more systematically than before... war was fought with ammunition and with the supply of food, not with money," highlighting the incommensurable nature of goods. This perspective led to Ludwig von Mises's famous 1920 essay, "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth", which argued against the possibility of rational economic calculation in a socialist system without market prices.

Neurath believed that "war socialism" would emerge after capitalism, noting its advantages in speed of decision-making, optimal resource distribution for military objectives, and efficient utilization of inventiveness. While acknowledging that centralized decision-making could reduce productivity and diminish the benefits of simple economic exchanges, he believed these drawbacks could be mitigated through "scientific" techniques, such as those advocated by Frederick Winslow Taylor, based on work-flow analysis. He maintained that socio-economic theory and scientific methods could be effectively applied in contemporary practice.

His views on socioeconomic development aligned with the materialist conception of history found in classical Marxism, which posits a conflict between technology and epistemology on one hand, and social organization on the other. Influenced also by James George Frazer, Neurath associated the rise of scientific thinking, empiricism, and positivism with the emergence of socialism. He saw both as being in conflict with older modes of epistemology, such as theology and idealist philosophy, which he believed served reactionary purposes. However, Neurath also followed Frazer in suggesting that primitive magic bore a close resemblance to modern technology, implying an instrumentalist interpretation of both. He contended that magic was unfalsifiable, and therefore, disenchantment could never be fully complete in a scientific age. Neurath predicted that under the socialist phase of history, the scientific worldview, which recognizes no authority other than science and rejects all forms of metaphysics, would become the dominant mode of thought.

5. Exile

Otto Neurath's life took a dramatic turn during the Austrian Civil War in 1934, forcing him into exile and leading him to continue his significant work in new environments.

5.1. Netherlands and British Isles

In 1934, while working in Moscow during the Austrian Civil War, Neurath received a coded message, "Carnap is waiting for you," signaling that it was unsafe for him to return to Austria. Consequently, he chose to travel to The Hague, Netherlands, to continue his international work. He was later joined by Gerd Arntz after affairs in Vienna were settled. His first wife, Olga Hahn-Neurath, also fled to the Netherlands, where she died in 1937.

Following the Rotterdam Blitz by the Luftwaffe, Neurath and Marie Reidemeister fled to Britain, crossing the English Channel in an open boat with other refugees. After a period of internment on the Isle of Man (Neurath was held in Onchan Camp), he and Marie Reidemeister married in 1941. In Britain, they established the Isotype Institute in Oxford. Neurath was also invited to advise on and design Isotype charts for the planned redevelopment of the slums in Bilston, near Wolverhampton, demonstrating the adaptability of his methods to new social contexts.

6. Philosophy and Thought

Otto Neurath's philosophical contributions were primarily focused on the philosophy of science and language, where he developed a distinctive approach, particularly his concept of physicalism, as a unifying framework for scientific knowledge.

6.1. Philosophy of Science and Language

Neurath's work on protocol statements sought to reconcile the empiricist emphasis on grounding knowledge in experience with the fundamental public nature of science. He proposed that reports of experience should be understood as having a third-person, public, and impersonal character, rather than being subjective, first-person pronouncements. This view was challenged by Bertrand Russell in his book An Inquiry Into Meaning and Truth, who argued that Neurath's account severed the essential connection to experience required for an empiricist understanding of truth, facts, and knowledge.

One of Neurath's most significant later works, Physicalism, profoundly reshaped the logical positivist discourse on the program of unifying the sciences. Neurath agreed with the general principles of the positivist program and its conceptual foundations: the construction of a universal system encompassing all knowledge from various sciences, and the absolute rejection of metaphysics, defined as any propositions not translatable into verifiable scientific sentences. However, he rejected the positivist treatment of language in general and, in particular, some of Ludwig Wittgenstein's early fundamental ideas.

Neurath dismissed the idea of isomorphism between language and reality as useless metaphysical speculation, arguing that it would necessitate explaining how words and sentences could represent external world objects. Instead, he proposed that language and reality coincide, with reality consisting simply of the totality of previously verified sentences within the language. For Neurath, the "truth" of a sentence was determined by its relationship to this totality of already verified sentences. If a sentence failed to "concord" or cohere with this totality, it should either be considered false, or some of the totality's existing propositions would need modification. Thus, he viewed truth as an internal coherence of linguistic assertions, rather than something connected to external facts. Furthermore, the criterion of verification, according to Neurath, should be applied to the system as a whole (a concept known as semantic holism) rather than to individual sentences. These ideas significantly influenced the holistic verificationism of Willard Van Orman Quine. Quine's book Word and Object popularized Neurath's famous analogy comparing the holistic nature of language and scientific verification to the reconstruction of a boat already at sea (similar to the Ship of Theseus paradox): We are like sailors who on the open sea must reconstruct their ship but are never able to start afresh from the bottom. Where a beam is taken away a new one must at once be put there, and for this the rest of the ship is used as support. In this way, by using the old beams and driftwood the ship can be shaped entirely anew, but only by gradual reconstruction.

Keith Stanovich discusses this metaphor in the context of memes and memeplexes, referring to it as a "Neurathian bootstrap".

Neurath also rejected the notion that science should be reconstructed in terms of sense data, arguing that perceptual experiences are too subjective to form a valid foundation for the formal reconstruction of science. He proposed that the phenomenological language emphasized by most positivists should be replaced by the language of mathematical physics. This shift would allow for the necessary objective formulations because it is based on spatio-temporal coordinates. Such a "physicalistic" approach to the sciences would facilitate the elimination of any residual metaphysical elements by reducing them to a system of assertions related to physical facts. Neurath further suggested that since language itself is a physical system, composed of an ordered succession of sounds or symbols, it is capable of describing its own structure without contradiction.

6.2. Physicalism

These ideas, particularly Neurath's physicalistic approach, were instrumental in forming the foundation of the kind of physicalism that remains a dominant position in metaphysics and especially the philosophy of mind. His emphasis on language as a physical system and the reduction of scientific assertions to physical facts aimed for a unified scientific worldview, free from metaphysical speculation.

7. Death

Otto Neurath died suddenly and unexpectedly from a stroke in December 1945.

8. Legacy and Influence

After Otto Neurath's death, Marie Neurath continued the work of the Isotype Institute. She was instrumental in publishing Neurath's writings posthumously, completing projects he had initiated, and authoring numerous children's books that utilized the Isotype system, continuing this work until her own death in the 1980s.

Neurath's work has had an enduring impact across various fields, including the philosophy of science, visual communication, economics, and social theory. His contributions to the philosophy of science, particularly his ideas on physicalism and the unity of science, continue to be relevant in discussions about scientific methodology and the nature of knowledge. His pioneering work with ISOTYPE laid the groundwork for modern information design and infographics, demonstrating the power of visual communication for accessible education and public understanding of complex data. In economics, his radical proposals for "in-kind" accounting and complete socialization sparked important debates about economic planning and the role of money.

While many of his publications and studies about him are still primarily available in German, Neurath also wrote in English, often utilizing Basic English. His scientific papers are preserved at the Noord-Hollands Archief in Haarlem, Netherlands, and the Otto and Marie Neurath Isotype Collection is held in the Department of Typography & Graphic Communication at the University of Reading in England.

9. Selected Publications

Otto Neurath's extensive published output spans philosophy, economics, sociology, and visual communication. A curated list of his significant works includes:

9.1. Books

- 1913. Serbiens Erfolge im Balkankriege: Eine wirtschaftliche und soziale Studie. Wien: Manz.

- 1921. Anti-Spengler. München: Callwey Verlag.

- 1926. Antike Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Leipzig, Berlin: B. G. Teubner.

- 1928. Lebensgestaltung und Klassenkampf. Berlin: E. Laub.

- 1933. Einheitswissenschaft und Psychologie. Wien.

- 1936. International Picture Language; the First Rules of Isotype. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & co., ltd.

- 1937. Basic by Isotype. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & co., ltd.

- 1939. Modern Man in the Making. Alfred A. Knopf.

- 1944. Foundations of the Social Sciences. University of Chicago Press.

- 1944. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science. With Rudolf Carnap and Charles W. Morris (eds.). University of Chicago Press.

- 1946. Philosophical Papers, 1913-1946: With a Bibliography of Neurath in English. Marie Neurath and Robert S. Cohen, with Carolyn R. Fawcett, eds. (Published 1983).

- 1946. From Hieroglyphics to Isotypes. Nicholson and Watson.

- 1973. Empiricism and Sociology. Marie Neurath and Robert Cohen, eds. Includes abridged translation of Anti-Spengler.

9.2. Articles

- 1912. "The problem of the pleasure maximum."

- 1913. "The lost wanderers of Descartes and the auxiliary motive."

- 1916. "On the classification of systems of hypotheses."

- 1919. "Through war economy to economy in kind."

- 1920a. "Total socialisation."

- 1920b. "A system of socialisation."

- 1928. "Personal life and class struggle."

- 1930. "Ways of the scientific world-conception."

- 1931a. "The current growth in global productive capacity."

- 1931b. "Empirical sociology."

- 1931c. "[http://amshistorica.unibo.it/diglib.php?inv=7&int_ptnum=50&term_ptnum=309&format=jpg Physikalismus]". In: Scientia: rivista internazionale di sintesi scientifica, 50, pp. 297-303.

- 1932. "Protokollsätze" (Protocol statements). In: Erkenntnis, Vol. 3.

- 1935a. "Pseudorationalism of falsification."

- 1935b. "The unity of science as a task."

- 1937. "[http://amshistorica.unibo.it/diglib.php?inv=7&int_ptnum=62&term_ptnum=317&format=jpg Die neue enzyklopaedie des wissenschaftlichen empirismus]". In: Scientia: rivista internazionale di sintesi scientifica, 62, pp. 309-320.

- 1938. "The Departmentalization of Unified Science." Erkenntnis VII, pp. 240-46.

- 1940. "Argumentation and action."

- 1941. "The danger of careless terminology." In: The New Era 22: 145-50.

- 1942. "International planning for freedom."

- 1943. "Planning or managerial revolution." (Review of J. Burnham, The Managerial Revolution). The New Commonwealth 148-54.

- 1943-5. Neurath-Carnap correspondence, 1943-1945.

- 1944b. "Ways of life in a world community." The London Quarterly of World Affairs, 29-32.

- 1945a. "Physicalism, planning and the social sciences: bricks prepared for a discussion v. Hayek."

- 1945b. Neurath-Hayek correspondence, 1945.

- 1945c. "Alternatives to market competition." (Review of F. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom). The London Quarterly of World Affairs 121-2.

- 1946a. "The orchestration of the sciences by the encyclopedism of logical empiricism."

- 1946b. "After six years." In: Synthese 5:77-82.

- 1946c. "The orchestration of the sciences by the encyclopedism of logical empiricism."