1. Overview

Oliver Norvell Hardy (born Norvell Hardy; January 18, 1892 - August 7, 1957) was an American comic actor, comedian, and film director, best known as one half of the iconic comedy duo Laurel and Hardy. His partnership with Stan Laurel, which began in the silent film era and lasted from 1926 to 1957, produced 107 short films, feature films, and cameo appearances, solidifying their status as legends in cinematic history. Hardy, often billed as "Babe Hardy" in his early silent films, was recognized for his distinctive physical comedy and his portrayal of the often exasperated but well-meaning "heavy" or "wise guy" character, contrasting with Laurel's skinny and childlike persona. Their unique blend of slapstick and character-driven humor earned them widespread popularity and critical acclaim, including an Academy Award for their short film The Music Box. Beyond his work with Laurel, Hardy also pursued solo projects, appeared in films with other notable actors, and engaged in live performances, leaving an indelible mark on comedy and popular culture.

2. Early Life and Background

Oliver Hardy's formative years were shaped by his family, early education, and a burgeoning interest in performance, which ultimately drew him away from traditional schooling and towards the entertainment world.

2.1. Birth and Family

Oliver Hardy was born Norvell Hardy on January 18, 1892, in Harlem, Georgia. While Harlem is widely cited as his birthplace, some sources suggest he may have been born in Covington, Georgia, his mother's hometown. His father, also named Oliver, was a veteran of the American Civil War, having served in the Confederate States Army. He was wounded during the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, and later served as a recruiting officer for Company K, 16th Georgia Regiment. The elder Oliver Hardy assisted his own father in managing the family's cotton plantation remnants before acquiring a share in a retail business and being elected as the full-time Tax Collector for Columbia County, Georgia. Hardy's mother, Emily Norvell, was the daughter of Thomas Benjamin Norvell, who was a descendant of Hugh Norvell of Williamsburg, Virginia, and Mary Freeman. His parents married on March 12, 1890; it was his mother's second marriage and his father's third.

The family relocated to Madison, Georgia, in 1891, the year before Norvell's birth. Tragically, his father passed away less than a year after his birth. Norvell was the youngest of five children. His older brother, Sam, drowned in the Oconee River; Hardy himself pulled his brother from the water but was unable to resuscitate him.

2.2. Education and Early Interests

As a child, Hardy exhibited a sometimes difficult temperament. In the fifth grade, he was enrolled at Georgia Military College in Milledgeville, Georgia. In 1905, at the age of 13, he attended Young Harris College in north Georgia for the fall semester, successfully completing it in January 1906, though he was part of the institution's junior high component, known today as an academy. Despite these educational attempts, he showed little interest in formal schooling. Instead, he developed an early and profound interest in music and theater. He joined a theatrical group and, at one point, ran away from a boarding school near Atlanta to sing with the troupe. Recognizing his vocal talent, his mother sent him to Atlanta to study music and voice under the singing teacher Adolf Dahm-Petersen. However, Hardy frequently skipped his lessons to perform as a singer at the Alcazar Theater, earning 3.5 USD per week. In 1912, he briefly enrolled in a law major at the University of Georgia for the fall semester, primarily to play football, a sport he never missed a game of.

2.3. Personal Development and Early Affiliations

During his teenage years, Norvell Hardy began to style himself as "Oliver Norvell Hardy," adopting "Oliver" as a tribute to his late father. He appeared as "Oliver N. Hardy" in the 1910 United States census and continued to use "Oliver" as his first name in all subsequent legal documents and marriage announcements. Hardy was initiated into Freemasonry at Solomon Lodge No. 20 in Jacksonville, Florida, an affiliation that provided him with support for room and board during his early days in show business. Later in his career, he was also inducted into the Grand Order of Water Rats alongside his comedy partner, Stan Laurel.

3. Career

Oliver Hardy's career trajectory spanned from his early days in silent cinema, where he developed his craft, to his eventual rise as an internationally beloved comedy icon, primarily through his legendary partnership with Stan Laurel.

3.1. Early Film Career

In 1910, The Palace, a motion picture theater, opened in Hardy's hometown of Milledgeville, where he took on various roles including projectionist, ticket taker, janitor, and manager. He quickly became captivated by the nascent motion picture industry, convinced that he could perform better than the actors he observed on screen. A friend suggested he move to Jacksonville, Florida, a burgeoning film production hub, which he did in 1913. In Jacksonville, he balanced his time working as a cabaret and vaudeville singer at night with daytime employment at the Lubin Manufacturing Company. It was during this period that he met Madelyn Saloshin, a pianist, whom he married on November 17, 1913, in Macon, Georgia.

The following year, Hardy made his film debut in Outwitting Dad (1914) for the Lubin studio, billed as O. N. Hardy. In his personal life, he was known as "Babe" Hardy, a name he would also use on screen in many of his subsequent films at Lubin, such as Back to the Farm (1914). Hardy was a large man, standing 6 ft 1 in (6.1 ft (1.85 m)) tall and weighing up to 300 lb (300 lb) (300 lb (136 kg)), a physique that often dictated the types of roles he could play. He was frequently cast as the villain, but also found roles in comedy shorts, where his size complemented his characters. By 1915, Hardy had appeared in 50 short one-reel films at Lubin. He then moved to New York, making films for Pathé, Casino, and Edison Studios. He later returned to Jacksonville to work for the Vim Comedy Company. This studio eventually closed after Hardy discovered that its owners were engaging in payroll theft. He then joined the King Bee studio, which acquired Vim, and collaborated with actors such as Billy Ruge, Billy West (a Charlie Chaplin imitator), and comedic actress Ethel Burton. He continued to play villainous roles for West well into the early 1920s, often imitating Eric Campbell to West's Chaplin.

Between 1916 and 1917, Hardy briefly ventured into directing, with credits for directing or co-directing ten shorts, all of which he also starred in.

In 1917, Hardy relocated to Los Angeles, working as a freelance actor for various Hollywood studios. He appeared in more than 40 films for Vitagraph between 1918 and 1923, predominantly playing the "heavy" or antagonist for Larry Semon. His personal life saw changes during this period; he separated from his first wife, Madelyn Saloshin, in 1919, with their provisional divorce granted in November 1920 and finalized on November 17, 1921. On November 24, 1921, he married actress Myrtle Reeves. This marriage, however, was also reportedly unhappy, with Reeves said to have struggled with alcoholism.

3.2. Formation of the Laurel and Hardy Partnership

Oliver Hardy's path to his legendary partnership with Stan Laurel involved several coincidental encounters and a gradual recognition of their comedic chemistry. In 1921, Hardy appeared in the film The Lucky Dog, which was produced by Broncho Billy Anderson and starred Stan Laurel. In this film, Hardy played a robber attempting to hold up Laurel's character. Despite this early collaboration, they did not work together again for several years.

In 1924, Hardy began working at Hal Roach Studios, known for its Our Gang films and collaborations with Charley Chase. The following year, his former boss, Larry Semon, cast him as the Tin Man in Semon's feature-film adaptation of The Wizard of Oz. In the same year, another former colleague, Billy West, recruited Hardy to star opposite the mild-mannered comic Bobby Ray in four slapstick comedies. These shorts, featuring Hardy and Ray as "fat-and-skinny" characters wearing derbies, served as early prototypes for the dynamic that would later define Laurel and Hardy's comedies. Hardy himself reflected on these films in 1954, stating, "Bobby was always the fall guy; I was the wise guy just as I am in Laurel and Hardy, only in Laurel and Hardy, *I* always am the fall guy. I think of [those pictures] once in a while as being the start of the Laurel and Hardy idea as far as I was concerned."

Hardy continued to work in Hal Roach comedies, including Yes, Yes, Nanette!, which starred Jimmy Finlayson and was directed by Stan Laurel. (Finlayson would later frequently appear as a supporting actor in the Laurel and Hardy film series.) Hardy also continued to play supporting roles in films featuring Clyde Cook, such as Wandering Papas (1925), also directed by Laurel.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1926 when Hardy was scheduled to appear in Get 'Em Young but was unexpectedly hospitalized after being severely burned by a hot leg of lamb. Stan Laurel, who was then working as a gag writer and director at Roach Studios, was recruited to fill in for Hardy. Although they did not share any scenes together, Laurel continued to act and appeared in 45 Minutes from Hollywood with Hardy.

The true formation of their partnership began in 1927 when Laurel and Hardy started sharing more screen time in films like Slipping Wives, Duck Soup (unrelated to the 1933 Marx Brothers' film), and With Love and Hisses. Leo McCarey, the supervising director at Roach Studios, observed the strong audience reaction to their combined presence and began intentionally teaming them together, leading to the official launch of the Laurel and Hardy series later that year. This pairing at Hal Roach Studios marked the beginning of one of the most successful and enduring comedy teams in cinematic history.

3.3. Major Works with Stan Laurel

The collaboration between Oliver Hardy and Stan Laurel at Hal Roach Studios resulted in a prolific output of short and feature films that defined their comedic style and cemented their legacy. They embarked on producing a vast body of short comedies, many of which are considered classics of the genre. Notable examples include The Battle of the Century (1927), famous for one of the greatest pie fights ever filmed; Should Married Men Go Home? (1928); and Two Tars (1928). Their transition to talking pictures began with Unaccustomed As We Are (1929), followed by other sound shorts like Berth Marks (1929), Blotto (1930), Brats (1930), Another Fine Mess (1930), and Be Big! (1931).

In 1929, they made their first feature film appearance in one of the revue sequences of Hollywood Revue of 1929. The following year, they provided comic relief in the lavish Technicolor musical feature The Rogue Song, which marked their first appearance in color, though only a few fragments of this film survive today. Their first full-length movie as stars was Pardon Us, released in 1931. They continued to produce both features and shorts until 1935. A significant achievement came in 1932 when their short film The Music Box won an Academy Award for Best Short Film, their only such accolade.

3.4. Later Career and Other Projects

After the peak of their Hal Roach Studios era, Oliver Hardy and Stan Laurel continued their careers, navigating new studio environments and exploring other performance avenues. In 1937, Oliver Hardy divorced his second wife, Myrtle Reeves. While a contractual issue between Stan Laurel and Hal Roach was being resolved, Hardy made the film Zenobia with Harry Langdon in 1939. Eventually, new contracts were agreed upon, and the comedy team was loaned to producer Boris Morros at General Service Studios to create The Flying Deuces (1939). It was during the production of this film that Hardy met Virginia Lucille Jones, a script girl, with whom he fell in love and married the following year. Their marriage proved to be a happy one, lasting for the remainder of his life.

In 1939, Laurel and Hardy completed A Chump at Oxford and Saps at Sea before departing from the Roach Studios. They then dedicated their efforts to supporting the Allied troops during World War II, performing for the USO.

In 1941, Laurel and Hardy signed contracts with 20th Century-Fox, followed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1942. These larger studios produced films on a grander scale, and initially, the comedians were hired primarily as actors in the B-picture division, with limited input on writing and editing decisions. Despite these constraints, their films proved very successful, and gradually both Laurel and Hardy were granted more creative control. They completed eight features during the war years, maintaining their popularity. The two-picture agreement with M-G-M concluded in August 1944, and Fox's series of six Laurel & Hardy pictures ended in December 1944 when the studio ceased B-picture production.

In 1947, Laurel and Hardy embarked on a six-week tour of the United Kingdom. Initially uncertain of their reception, they were met with overwhelming enthusiasm and were mobbed wherever they went. The success of the tour led to its extension, including engagements in Scandinavia, Belgium, France, and a prestigious Royal Command Performance for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Biographer John McCabe noted that they continued to make live appearances in the United Kingdom and France until 1954, often performing new sketches and material written by Laurel.

In 1949, Hardy's friend John Wayne invited him to play a supporting role in The Fighting Kentuckian. Hardy had previously collaborated with Wayne and John Ford in a charity production of the play What Price Glory? a few years prior, while Laurel had begun treatment for his diabetes. Hardy was initially hesitant about the role but accepted at Laurel's insistence. The following year, in 1950, Frank Capra invited Hardy to make a cameo appearance in Riding High with Bing Crosby.

Between 1950 and 1951, Laurel and Hardy filmed their final cinematic collaboration, Atoll K (also known as Utopia). The film's premise was simple: Laurel inherits an island, and the duo sets sail, encountering a storm that leads them to discover a new island rich in uranium, making them powerful and wealthy. However, the production was plagued by difficulties, as it was produced by a consortium of European interests with an international cast and crew who often faced language barriers. Furthermore, Laurel had to extensively rewrite the script to align it with the comedy team's distinctive style, and both actors suffered serious physical illnesses during the filming, which impacted the production.

3.5. Television and Final Appearances

Oliver Hardy and Stan Laurel made two notable live television appearances during their later years. In 1953, they were featured on a live broadcast of the BBC show Face the Music. The following year, in December 1954, they appeared on NBC's This Is Your Life. Their final appearance together was a filmed insert for the BBC show This Is Music Hall in 1955.

In 1955, the pair signed a contract with Hal Roach Jr. to produce a series of television shows based on Mother Goose fables. According to biographer John McCabe, these shows were intended to be filmed in color for NBC. However, the series was postponed when Stan Laurel suffered a stroke, requiring a lengthy period of convalescence. Later that same year, while Laurel was still recovering, Oliver Hardy experienced a heart attack and a stroke, from which he never fully recovered, marking the end of his active career.

4. Personal Life

Oliver Hardy's personal life included three marriages, each bringing different experiences to his life outside of his celebrated career. His first marriage was to Madelyn Saloshin, a pianist, on November 17, 1913, in Macon, Georgia. The couple separated in 1919, and their provisional divorce was granted in November 1920, finalized on November 17, 1921.

On November 24, 1921, he married actress Myrtle Reeves. This second marriage was reportedly unhappy, with accounts suggesting that Reeves struggled with alcoholism. Their marriage ended in divorce in 1937.

Hardy's third and final marriage was to Virginia Lucille Jones, a script girl whom he met on the set of The Flying Deuces in 1939. They married the following year and enjoyed a happy and stable marriage for the remainder of Hardy's life. Lucille remained his devoted caretaker during his final years of declining health.

5. Health and Later Years

Oliver Hardy's later years were marked by a significant decline in his health. In May 1954, he experienced a mild heart attack, which prompted him to seriously address his health for the first time in his life. He embarked on a rigorous weight loss regimen, shedding more than 150 lb (150 lb) (150 lb (68 kg)) in just a few months, a transformation that dramatically altered his appearance.

Letters written by Stan Laurel during this period suggest that Hardy was suffering from terminal cancer, a condition speculated to be the underlying cause of his rapid and significant weight loss. Both Hardy and Laurel were heavy smokers; film producer Hal Roach famously described them as "a couple of freight train smoke stacks" due to their smoking habits.

On September 14, 1956, Hardy suffered a major stroke that left him confined to bed and unable to speak for several months. He remained at home, receiving care from his devoted wife, Lucille.

6. Death

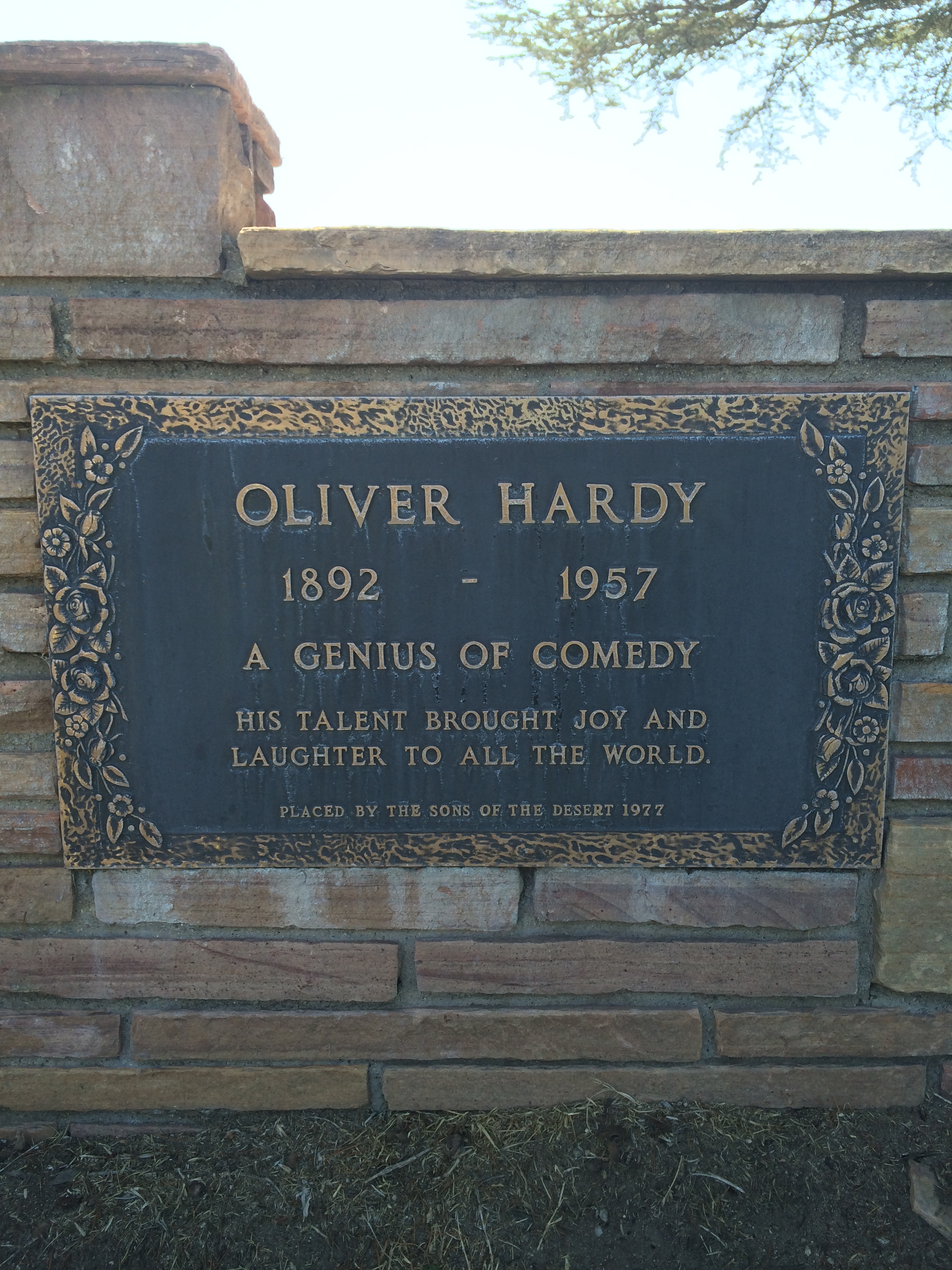

Following two additional strokes in early August 1957, Oliver Hardy slipped into a coma. He died from cerebral thrombosis on August 7, 1957, at the age of 65. After his death, his body was cremated, and his ashes were interred in the Masonic Garden of Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood, California.

Stan Laurel was deeply affected by the loss of his "dear pal and partner." Due to his own poor health, Laurel's doctor advised him against attending Hardy's funeral. Laurel agreed, stating that "Babe would understand," a testament to their profound bond.

7. Legacy and Recognition

Oliver Hardy's contributions to comedy and cinema have left an enduring legacy, ensuring his place as one of the most influential figures in entertainment history. His comedic timing, expressive facial reactions, and physical presence, particularly as the "heavy" or "wise guy" opposite Stan Laurel's "fall guy," created a timeless dynamic that continues to entertain audiences worldwide.

Hardy's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is located at 1500 Vine Street in Hollywood, California, commemorating his significant impact on the film industry. He was also inducted into the Grand Order of Water Rats alongside Stan Laurel, recognizing their contributions to entertainment.

In his hometown of Harlem, Georgia, a small Laurel and Hardy Museum was established, opening on July 15, 2002, to celebrate his life and work. The town further honors his memory with an annual Oliver Hardy Festival.

His life and partnership with Stan Laurel were brought to the big screen in the 2018 biographical film Stan & Ollie, with John C. Reilly portraying Hardy and Steve Coogan as Laurel, which garnered critical acclaim for its depiction of their later years and enduring friendship.

Beyond these direct tributes, Oliver Hardy's influence extends into popular culture, with his image and comedic style frequently referenced. The asteroid (2866) Hardy was named in his honor, further cementing his recognition.