1. Overview

Nynetjer, also known as Ninetjer or Banetjer, was the third pharaoh of the Second Dynasty of Egypt during the Early Dynastic Period. His Horus name, Nynetjer, translates to "Godlike" or "Divine One," reflecting his revered status. Nynetjer is historically significant as the most archaeologically attested ruler of the entire Second Dynasty, with numerous inscriptions and artifacts bearing his name. He succeeded Raneb on the throne, inheriting a unified Egyptian state.

Nynetjer's reign is a subject of considerable scholarly debate, particularly regarding its duration and the circumstances surrounding its conclusion. Estimates for his rule range from 43 to 50 years, with some ancient sources proposing even longer or shorter periods. His long reign saw significant administrative and religious developments, including the formalization of the "Following of Horus" census for taxation and resource management, and the increasing prominence of sun worship and the cult of Ra.

However, the end of Nynetjer's rule is shrouded in uncertainty, with historical sources and archaeological evidence suggesting a possible breakdown or partition of the Egyptian state. Scholars propose various theories for this disunity, including political instability, regional and religious conflicts between Upper and Lower Egypt, deliberate administrative division by Nynetjer himself, or economic crises such as famine. These theories highlight a period of transition and challenges in early dynastic governance. His tomb at Saqqara, known as Gallery Tomb B, is a monumental underground structure that provides invaluable insights into the royal mortuary architecture and funerary practices of the period, serving as an enduring memorial to his impactful reign.

2. Identity and Background

Nynetjer's identity as a pharaoh is well-established through various historical and archaeological records. His name is central to understanding the early period of the Second Dynasty.

2.1. Horus Name and Meaning

Nynetjer is primarily known by his Horus name, Nynetjer (or Ninetjer), which is interpreted to mean "Godlike" or "Divine One." He is also referred to as Banetjer in the Abydos King List, Banetjeru in the Saqqara King List, and Netjer-ren in the Royal Canon of Turin.

An unusual depiction of his name appears on a rock inscription near Abu Handal in Lower Nubia. In this inscription, the serekh of the king features only a "N" sign, with the word "Netjer" (meaning "God") placed above the serekh, in the position typically occupied by the Horus falcon. This renders Nynetjer's name as "The God N". The absence of the Horus falcon in this context has led some scholars to suggest potential religious disturbances or shifts in royal ideology during or after his reign. This is further supported by the later choices of kings like Peribsen, who used Set instead of Horus above his serekh, and Khasekhemwy, who featured both gods facing each other.

The Palermo Stone also presents an unusual gold name for Nynetjer: Ren-nebu, meaning "golden offspring" or "golden calf". This name, which appears on artifacts from Nynetjer's lifetime, is considered by Egyptologists such as Wolfgang Helck and Toby Wilkinson to be a precursor to the later Golden Horus name, which became a standard part of the royal titulature during the Third Dynasty of Egypt under king Djoser.

2.2. Succession and Dynasty

Nynetjer holds the position of the third pharaoh of the Second Dynasty of Egypt. He directly succeeded Raneb on the throne. This succession order is consistently supported by contemporary and historical sources.

Archaeological evidence, such as the statue of Hetepedief, a priest of the mortuary cults of the first three kings of the dynasty, corroborates this sequence. The statue, found in Memphis and crafted from speckled red granite, displays the serekhs of Hotepsekhemwy, Raneb, and Nynetjer inscribed chronologically on Hetepedief's right shoulder. Further support comes from stone bowls belonging to Hotepsekhemwy and Raneb that were reinscribed during Nynetjer's reign. Additionally, the Old Kingdom royal annals, while not explicitly naming Nynetjer's predecessor, are consistent with him not being the first ruler of the Second Dynasty. The Turin King List, compiled much later under Ramesses II, explicitly ranks Nynetjer as the third king of his dynasty, after Hotepsekhemwy and Raneb, reinforcing his established place in the lineage of early dynastic Egypt.

3. Chronology and Reign Duration

Determining the precise chronology and duration of Nynetjer's reign has been a complex challenge for Egyptologists, with various ancient and modern sources offering differing accounts.

3.1. Dating Estimates

Nynetjer's reign is generally estimated by most experts to have occurred sometime during the late 29th century BC to the early 27th century BC. More specific estimates place his rule from around 2850 BC to 2760 BC, or alternatively, a later period from approximately 2760 BC to 2715 BC. One account specifically dates his reign to about 2808 BC to 2761 BC. These variations reflect the challenges in reconciling ancient records and archaeological findings.

3.2. Reign Length

The length of Nynetjer's rule is highly debated. The Turin Canon suggests an improbable reign of 96 years, which Egyptologists generally regard as a misinterpretation or exaggeration. The Egyptian historian Manetho, writing over two millennia later, claimed Nynetjer's reign lasted 47 years; however, this account is also viewed with skepticism by modern scholars.

Modern Egyptologists, based on comprehensive analysis of available evidence, generally credit Nynetjer with a reign of either 43 or 45 years. More detailed reconstructions of the Old Kingdom royal annals, particularly the Palermo Stone, which records events from what is likely the 7th to the 21st year of his reign, suggest a longer rule. Although much of the original record is lost, space analysis on the annals has led to estimations ranging from 38 to 49 years for his total time on the throne. Toby Wilkinson's 2000 reconstruction, for instance, concludes that Nynetjer's reign, as documented on the Palermo Stone, most probably spanned 40 complete or partial years.

Further archaeological evidence supports a lengthy reign. A seated statuette of Nynetjer depicts him wearing the ceremonial, tight-fitting vestment associated with the sed festival. This royal jubilee, a feast for the rejuvenation of the king, was typically celebrated for the first time only after a monarch had reigned for 30 years. This depiction thus implies a reign duration of at least 30 years, lending credibility to the longer estimates.

4. Attestations and Evidence

Nynetjer stands out as the most extensively attested king of the early Second Dynasty, with a significant amount of archaeological and historical evidence confirming his existence and providing insights into his rule.

4.1. Archaeological Finds

A substantial body of physical evidence from Nynetjer's reign has been discovered. His name frequently appears in inscriptions on stone vessels and on numerous clay sealings originating from his tomb at Saqqara. A significant quantity of artifacts bearing his name has also been found in the tomb of king Peribsen at Abydos and within the galleries beneath the step pyramid of king Djoser.

However, dating some of these inscriptions, particularly those made with black ink, has presented challenges. Writing experts and archaeologists, including Ilona Regulski, suggest that the ink inscriptions are of a somewhat later date than the stone and seal inscriptions. Regulski dates these ink markings to the reigns of kings such as Khasekhemwy and Djoser, hypothesizing that these artifacts originally came from Abydos. Indeed, alabaster vessels and earthen jars bearing black ink inscriptions with a very similar font style, featuring Nynetjer's name, were recovered from Peribsen's tomb, supporting this theory.

Further archaeological attestation includes a rock inscription near Abu Handal in Lower Nubia. This inscription features an "N" sign within the king's serekh, uniquely accompanied by the "Netjer" sign for "God" placed above the serekh, in the position typically occupied by the Horus falcon. This renders Nynetjer's name as "The God N". The unusual absence of Horus in this context may subtly hint at religious shifts or disturbances, preceding the more explicit religious choices of later pharaohs like Peribsen, who prominently featured the god Set, and Khasekhemwy, who incorporated both Set and Horus. The existence of this inscription itself could indicate a military expedition led by Nynetjer into this region, possibly after his 20th year of rule, as no such expedition is mentioned in the surviving royal annals covering his first two decades.

The relative chronological position of Nynetjer as the third ruler of the Second Dynasty and successor of Raneb is also directly attested by the contemporary statue of Hetepedief. This speckled red granite statue, discovered in Memphis, is one of the earliest examples of private Egyptian sculpture. Hetepedief served as a priest of the mortuary cults for the dynasty's first three kings, whose serekhs-Hotepsekhemwy, Raneb, and Nynetjer-are inscribed in a seemingly chronological order on his right shoulder.

4.2. King Lists and Inscriptions

Nynetjer's reign is confirmed and documented across several ancient king lists and royal inscriptions that serve as crucial historical sources. He is consistently identified in major king lists from later periods.

In the Abydos King List, Nynetjer appears under the Ramesside cartouche name Banetjer, listed as entry number 11. The Saqqara King List records him as Banetjeru, while the Royal Canon of Turin refers to him as Netjer-ren. These lists, though compiled centuries after his reign, attest to his recognized place in the royal succession.

The Palermo Stone, a primary source for the Early Dynastic Period, includes an unusual gold name of Nynetjer: Ren-nebu, which translates to "golden offspring" or "golden calf". This name, which appears on artifacts from Nynetjer's lifetime, is considered by Egyptologists to be an early form or forerunner of the Golden Horus name that became a formal part of the royal titulature in the Third Dynasty of Egypt, particularly under King Djoser. The Palermo Stone itself is considered a highly reliable record of Nynetjer's rule because it correctly preserves his name, unlike some of the more "corrupt, garbled variants" found in later king lists.

5. Reign Events

Much of the information regarding Nynetjer's reign comes from fragments of the Old Kingdom royal annals, most notably the Palermo Stone and the Cairo Stone. These inscriptions provide insights into the religious, administrative, and environmental aspects of his rule.

5.1. Palermo Stone Records

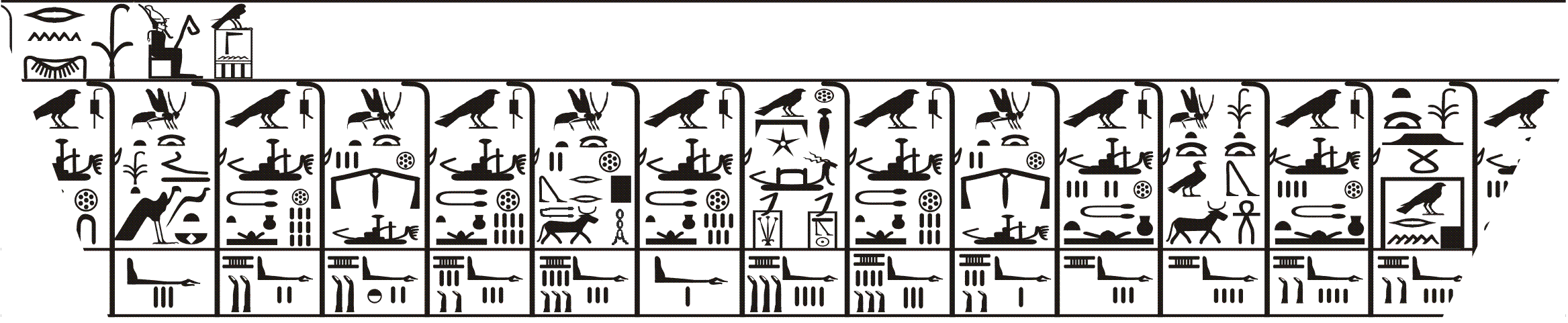

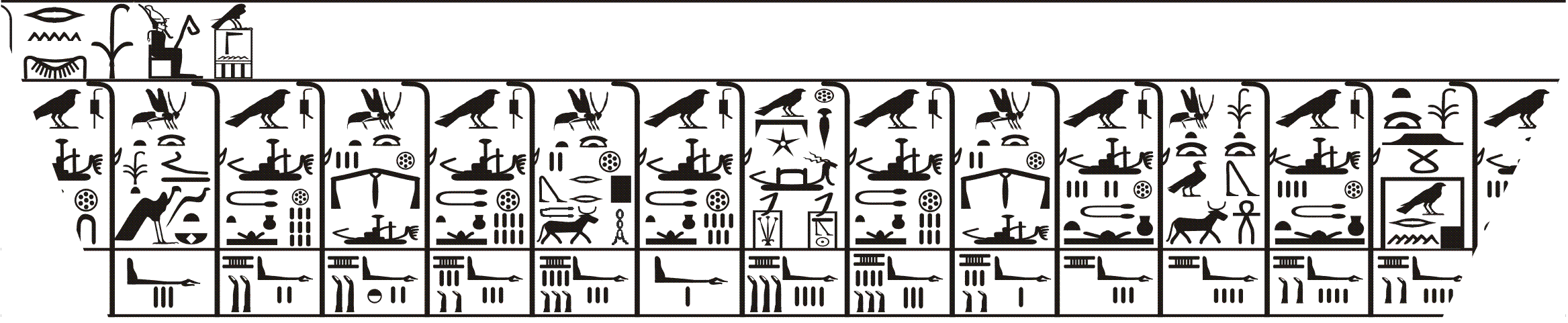

The Palermo Stone, the main fragment of the Annal Stone of the Fifth Dynasty, records various events from what is believed to be the 7th through the 21st year of Nynetjer's reign. Each entry details key administrative and religious activities, alongside Nile flood levels, which were crucial for ancient Egyptian agriculture and prosperity.

- 7th year: Following of Horus (the rest is missing from the fragment).

- 8th year: Appearance of the king; "stretching the cords" (a ceremony for a foundation) for "Hor-Ren". Flood level: 5.2 ft (1.57 m).

- 9th year: Following of Horus. Flood level: 3.6 ft (1.09 m). One account also mentions an Apis bull race during this year.

- 10th year: Appearance of the king of Lower- and Upper Egypt; "Race of the Apis bull" (pḥrr Ḥp'Egyptian (Ancient)). Flood level: 3.6 ft (1.09 m).

- 11th year: Following of Horus. Flood level: 6.5 ft (1.98 m).

- 12th year: Appearance of the king of Lower Egypt; second celebration of the Sokar feast. Flood level: 6.3 ft (1.92 m).

- 13th year: Following of Horus. Flood level: 1.7 ft (0.52 m). One record states that the city of "Shem-Re" and "Ha" (meaning "The northern city") were attacked in this year.

- 14th year: First celebration of "Hor-seba-pet" (Horus the star in heaven); Destruction or Foundation of "Shem-Re" and "Ha" (The northern city). The interpretation of this passage is debated, as the hieroglyphic sign of a hoe can signify either 'destruction' or 'foundation'. Flood level: 7.1 ft (2.15 m).

- 15th year: Following of Horus. Flood level: 7.1 ft (2.15 m). One account suggests that Khasekhemwy was born in this year.

- 16th year: Appearance of the king of Lower Egypt; second "Race of the Apis bull" (pḥrr Ḥp'Egyptian (Ancient)). Flood level: 6.3 ft (1.92 m).

- 17th year: Following of Horus. Flood level: 7.9 ft (2.4 m).

- 18th year: Appearance of the king of Lower Egypt; third celebration of the Sokar feast. Flood level: 7.3 ft (2.21 m).

- 19th year: Following of Horus. Flood level: 7.4 ft (2.25 m).

- 20th year: Appearance of the king of Lower Egypt; offering for the king's mother; celebration of the "Feast of eternity" (a burial ceremony). Flood level: 6.3 ft (1.92 m).

- 21st year: Following of Horus (the rest is missing).

5.2. Cairo Stone Records

The Cairo Stone, another significant fragment of the royal annals, records events from later in Nynetjer's reign, specifically covering years 36 through 44. The surface of this stone slab is considerably damaged, making much of its content illegible. However, decipherable fragments include references to the "birth" (creation) of an Anubis fetish and parts of an "Appearance of the king of Lower- and Upper Egypt."

5.3. Other Recorded Events

Beyond the annals, other historical accounts offer glimpses into Nynetjer's rule. The ancient Egyptian historian Manetho, writing significantly later, referred to Nynetjer as Binôthrís. Manetho notably claimed that during Nynetjer's reign, "women received the right to gain royal dignity," implying that women were granted the authority to rule as monarchs. Egyptologists, such as Walter Bryan Emery, suggest that this statement may have been an obituary or a historical reference to earlier queens like Meritneith and Neithhotep from the early First Dynasty of Egypt, who are believed to have held the Egyptian throne for several years when their sons were too young to rule.

The rock inscription found near Abu Handal in Lower Nubia may indicate that Nynetjer dispatched a military expedition to this region. Given that the surviving royal annals do not mention such an expedition within his first two decades of rule, this event likely occurred after his 20th year on the throne, suggesting a continued active engagement in territorial affairs or resource acquisition throughout his long reign.

6. Administration and Religious Developments

Nynetjer's reign marked a period of notable administrative evolution and significant religious developments, shaping the future trajectory of the Egyptian state.

6.1. Administrative Reforms

Nynetjer's reign witnessed important administrative innovations aimed at centralizing state control and managing resources more effectively. The biennial event known as the "Following of Horus" (mentioned frequently on the Palermo Stone) most probably involved the king and the royal court undertaking a journey throughout Egypt. From at least Nynetjer's rule onwards, the primary purpose of this royal journey was to conduct a comprehensive census for taxation, as well as to collect and distribute various commodities. An historical source from the Third Dynasty explicitly details that this census included an "enumeration of gold and land," highlighting its economic significance.

The responsibility for overseeing state revenues during Nynetjer's time fell under the authority of the chancellor of the treasury. Nynetjer himself is credited with introducing three new administrative institutions to replace an older, less efficient one, indicating a restructuring of the bureaucracy. He may also have established an office dedicated to food management, which would have been directly linked to the census efforts.

By the beginning of the Third Dynasty, the "Following of Horus" system began to fade from records, replaced by an even more thorough census, a development that might have originated during Nynetjer's reign. This expanded census later, from at least the reign of Sneferu onwards, specifically included "cattle counts," under which name it became widely known, with oxen and small livestock explicitly recorded from the Fifth Dynasty onwards.

These administrative innovations represent a qualitatively new stage in resource collection and management for the emerging Egyptian state. They built upon earlier foundations, such as the institutions responsible for royal tomb preparation, funerary cult upkeep, and the state treasury, which were established in the mid-First Dynasty. The early dynastic treasury, rather than a modern financial institution, primarily administered agricultural produce and stone ware, crucial components for funerary furniture. The ritualized supply of these items to the royal tomb played a significant role in the ideology of early kingship. Nynetjer's reforms undoubtedly necessitated an increase in the size of the civil service, whose main objective was to ensure the sustained existence and effectiveness of kingship, including providing for the king's needs in the afterlife. This, in turn, required the regular collection of increasing quantities of commodities, as Second Dynasty royal tombs were designed to mimic the king's palace, incorporating numerous storage rooms for provisions like wine and food.

6.2. Religious Practices and Beliefs

The reigns of both Raneb and Nynetjer are recognized for the notable development of sun worship and the burgeoning cult of Ra. This period saw an increasing emphasis on solar deities, foreshadowing the later prominence of Ra in the Egyptian pantheon.

The Palermo Stone, specifically its record for the 14th year of Nynetjer's reign, may refer to a significant religious event: the foundation of an institution or building called "Shem-Re". The name "Shem-Re" has been variously translated as "The going of Ra," "The sun proceeds," or "The sun has come," all indicating a strong connection to the sun god. This foundation, if indeed it was a religious establishment, would underscore the growing importance of Ra worship during Nynetjer's time.

Furthermore, the rock inscription in Lower Nubia, which renders Nynetjer's name as "The God N" by placing the "Netjer" sign above his serekh instead of the traditional Horus falcon, subtly hints at potential religious disturbances or evolving theological concepts. This unusual representation may reflect underlying tensions or emerging alternatives to the dominant Horus cult, a trend that would become more explicit with later pharaohs like Peribsen, who openly favored the god Set, and Khasekhemwy, who attempted to reconcile both Horus and Set in his royal titulature. Peribsen's choice of Set, an Upper Egyptian god from Ombos, further suggests a regional component to these religious shifts.

7. End of Reign and State Division Theories

The circumstances surrounding the end of Nynetjer's long reign and the immediate period thereafter are fraught with uncertainty, leading to several scholarly theories regarding potential political instability and the fragmentation of the Egyptian state.

7.1. Theories of Political and Economic Instability

The period following Nynetjer's rule is highly debated among Egyptologists, with historical records preserving conflicting lists of kings leading up to the reign of Khasekhemwy. It is plausible, though not definitively certain, that Egypt experienced civil unrest or a breakdown of centralized authority. This could have led to the emergence of competing claimants to the throne, possibly reigning concurrently over separate realms in Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. Three main hypotheses have been proposed to explain these observations: a political breakdown possibly intertwined with religious conflict, a deliberate decision by Nynetjer for administrative efficiency, or an economic collapse that triggered Egyptian disunity.

7.2. Religious and Regional Conflicts

One prominent theory, advanced by scholars like Erik Hornung and Hermann Alexander Schlögl, suggests that the troubles originated from an Upper Egyptian reaction to a perceived shift of power and royal interest towards Memphis and Lower Egypt. This shift is evidenced by the abandonment of the First Dynasty necropolis at Abydos in favor of Saqqara, where the tombs of the first three kings of the Second Dynasty were constructed.

This political conflict may have also acquired a religious dimension under Nynetjer's successors. Hornung and Schlögl point to King Peribsen's controversial choice to feature the god Set, an Upper Egyptian deity originating from Ombos, as the divine patron for his name, rather than the traditional Horus. Peribsen further asserted his Upper Egyptian ties by choosing to build his tomb in the older royal burial grounds of Abydos, where he also erected a funerary enclosure. In response to these developments, it is believed that a counter-movement emerged in Lower Egypt, with kings who associated themselves with Horus ruling concurrently over the northern part of the country.

7.3. Deliberate Administrative Division

In contrast to theories of conflict, Egyptologists such as Wolfgang Helck, Nicolas Grimal, Hermann Alexander Schlögl, and Francesco Tiradritti propose that Nynetjer intentionally divided the realm. They believe that Nynetjer found the state administration to be overly complex and unwieldy, potentially deciding to split Egypt between two successors, possibly his own sons. The hope behind such a radical move would have been that two separate rulers could more effectively administer the divided kingdoms, thereby improving overall governance and stability.

7.4. Economic Collapse Theory

Another significant theory, put forth by Egyptologist Barbara Bell, suggests that an economic catastrophe, such as a prolonged famine or drought, afflicted Egypt around the end of Nynetjer's reign. According to Bell, Nynetjer might have divided the realm into two in an effort to better address the problem of feeding the Egyptian population, with his successors governing independent states until the crisis subsided. Bell supported her hypothesis by interpreting the records of the annual Nile floods on the Palermo Stone, which, in her view, showed consistently low levels during this period.

However, Bell's famine theory has largely been refuted by subsequent Egyptologists, notably Stephan Seidlmayer. Seidlmayer corrected Bell's calculations, demonstrating that the annual Nile floods during Nynetjer's time and up to the period of the Old Kingdom were actually at their usual levels. Seidlmayer highlighted that Bell had overlooked a crucial detail: the flood heights recorded on the Palermo Stone only reflected measurements from nilometers located around Memphis, without accounting for readings from other points along the Nile River. Therefore, a long-lasting, widespread drought is considered an unlikely explanation for the state's disunity.

7.5. Succession and Re-unification

The precise sequence of succession following Nynetjer's reign and whether the Egyptian state was already divided at the time of his death remain unclear. All known king lists, including the Saqqara King List, the Turin Canon, and the Abydos King List, consistently list a king named Wadjenes as Nynetjer's immediate successor, followed by a king named Senedj. However, after Senedj, these king lists diverge significantly regarding subsequent rulers.

While the Saqqara list and the Turin Canon mention kings such as Neferka(ra) I, Neferkasokar, and Hudjefa I as direct successors, the Abydos list omits these names, instead listing a king named Djadjay, who is identified with king Khasekhemwy. This discrepancy supports the theory of a divided state. If Egypt was indeed already fragmented when Senedj ascended the throne, it is hypothesized that kings like Sekhemib and Peribsen may have ruled Upper Egypt, while Senedj and his successors-Neferka(ra) I and Hudjefa I-controlled Lower Egypt. This period of division or fragmentation was eventually brought to an end by King Khasekhemwy, who is credited with reunifying Egypt under a single rule.

8. Tomb and Mortuary Architecture

Nynetjer's tomb at Saqqara is a significant archaeological discovery, offering profound insights into early dynastic royal mortuary architecture, funerary practices, and the material culture of the period.

8.1. Discovery and Location

Nynetjer's tomb was discovered by Selim Hassan in 1938, during his excavations of mastabas under the auspices of the Service des Antiquités de l'Egypte, in the vicinity of the Pyramid of Unas. Hassan initially proposed that Nynetjer was the tomb's owner based on numerous seal impressions bearing the pharaoh's serekh found at the site. This identification was later confirmed by subsequent excavations in the 1970s and 1980s led by Peter Munro and Günther Dreyer, respectively. Thorough excavations have continued until the 2010s under the supervision of archaeologist Claudia Lacher-Raschdorff of the German Archaeological Institute. An earlier misconception had led to the large mastaba of the high official Ruaben (or Ni-Ruab), known as mastaba S2302, being proposed as Nynetjer's tomb due to a large number of Nynetjer's clay seals found there; however, it was later confirmed to belong to Ruaben, who served during Nynetjer's reign.

Nynetjer's tomb, now designated as Gallery Tomb B, is situated in North Saqqara. Its ancient name might have been "Nurse of Horus" or "Nurse of the God." The tomb's location, intentionally out of sight of Memphis and adjacent to a natural wadi running west to east, served practical and symbolic purposes. The wadi likely functioned as a causeway for transporting construction materials from the valley to the plateau, while also ensuring the tomb remained hidden from the Nile valley. This placement within a desert backdrop symbolized death, which the king was believed to transcend.

The tomb lies in the immediate vicinity of the burial sites of Nynetjer's predecessors, Hotepsekhemwy and Raneb. Currently, it is located beneath the causeway of Unas, constructed at the end of the Fifth Dynasty. By that time, the original entrance to Nynetjer's tomb had already been blocked by a ditch that Djoser had dug around his own pyramid. Any above-ground structures that may have been associated with Nynetjer's tomb have been largely destroyed, possibly during Unas's rule or even earlier under Djoser's. To the south and east of the tomb, archaeological evidence suggests the presence of a broader necropolis from the Second Dynasty, containing the gallery tombs of several high-ranking officials of the era. According to Erik Hornung, the choice of Saqqara over the traditional Abydos burial grounds of the First Dynasty suggests a potential neglect of the older Upper Egyptian center of power in favor of Memphis, a factor that might have contributed to an Upper Egyptian backlash in the tumultuous period following Nynetjer's rule.

8.2. Architectural Features

Archaeological investigations indicate that Nynetjer's tomb originally possessed above-ground structures, though none have survived. Insufficient remains make it impossible to determine their precise layout or whether they were constructed of mud-brick or limestone. However, it is highly probable that these superstructures incorporated an offering place with a false door and niche stele, a mortuary temple, and a serdab. These above-ground components may have reached heights of 26 ft (8 m) to 33 ft (10 m), potentially resembling a Mastaba. It is also likely that a separate enclosure wall, built of stone, accompanied the tomb, similar to those surrounding royal tombs since the First Dynasty but potentially on a much grander scale. The nearby Gisr el-Mudir and L-shape enclosures may belong to Hotepsekhemwy and Nynetjer.

The tomb's substructures comprise two extensive subterranean complexes, meticulously hewn into the local rock. The main ensemble is dug approximately 16 ft (5 m) to 20 ft (6 m) below ground level and features 157 rooms, each about 6.9 ft (2.1 m) in height, spanning an area of approximately 77 by 50.5 meters. The second, smaller ensemble consists of 34 rooms.

Access to the tomb was originally provided by a 82 ft (25 m)-long ramp, which was secured by two portcullises. This ramp led to three main galleries, arranged along a rough east-west axis. These galleries, in turn, extended into a complex, maze-like system of doorways, vestibules, and corridors, indicative of two distinct construction phases. Claudia Lacher-Raschdorff estimates that the tomb's vast network of rooms and galleries could have been excavated by a team of approximately 90 individuals working over a period of two years. Marks left by copper tools indicate that workers were organized into several groups, hewing the rock from different directions simultaneously.

Nynetjer's tomb represents a significant evolutionary step in monumental royal mortuary architecture. Its extended layout, incorporating numerous storage rooms, transformed the tomb itself into a central location for the performance of funerary rituals. A group of chambers at the southern end of the tomb appears to be a model of the royal palace, further emphasizing the connection between the earthly and afterlife residences of the pharaoh. The tomb exhibits considerable architectural similarities to Gallery Tomb A, believed to be the burial site of either Raneb or Hotepsekhemwy. This led the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) to conclude that Nynetjer drew inspiration from his predecessors' tombs in the design of his own. The main burial chamber was situated at the southwestern end of the tomb, but the entire site is presently highly unstable and faces a significant risk of collapse.

8.3. Burial Goods and Contents

Remarkably, some chambers within Nynetjer's tomb were discovered almost undisturbed, still containing a portion of the pharaoh's original burial goods. One such room yielded 560 jars of wine, some of which remained sealed with impressions bearing the king's name and were covered by a thick net woven from plant fibers. Another chamber contained fragments of an additional 420 unfinished and unsealed wine jars, which appear to have been deliberately broken as part of a burial ceremony.

Further vessels recovered included a group decorated with distinctive red stripes, which held jujube fruits, and fewer than ten jars that once contained beer. Excavations also brought to light a significant collection of stone tools, numbering between 144 and 151 pieces. This collection comprised various implements, including knives (both with and without handles), stone sickles, blades, scrapers, and hatchets, along with numerous additional fragments of stone tools. The tomb also contained many intact stone vessels and unworked pieces of stone, presumably left for the production of further vessels in the afterlife.

Detailed examination of the stone tools revealed only minor traces of use and residues of a reddish-brown liquid, with no identifiable wear suggesting intensive use or resharpening. This led Claudia Lacher-Raschdorff to hypothesize that these tools were specifically crafted for the king's burial and employed during a ceremony involving the ritual slaughtering of animals and the preparation of food. In addition, pieces of carved wood discovered in the tomb suggest the presence of a tent or canopy among the king's mortuary equipment, similar to one found in the later tomb of Queen Hetepheres I (fl. c. 2600 BC). Interestingly, some of the wine jars found in Nynetjer's tomb were identified as originating from the tombs of the late First Dynasty of Egypt, indicating a continuation of practices or perhaps an intentional symbolic connection to earlier royal burials.

8.4. Later Usages

The northern part of Nynetjer's gallery tomb area was subsequently covered by the necropolis associated with the Pyramid of Unas at the end of the Fifth Dynasty. Evidence suggests that Nynetjer's tomb was partially re-used during the New Kingdom. A mummy mask and a woman's coffin dating to the Ramesside era were discovered within the tomb, indicating later interments. During this time, an extensive private necropolis developed across the entire area of the tomb. This necropolis continued to be utilized until the Late Period and, more sporadically, into the early Christian period, coinciding with the construction of the nearby monastery of Jeremiah.

9. Personal Life and Governance Philosophy

Insights into Nynetjer's personal life and his approach to governance are largely inferred from later historical accounts and the administrative and political changes observed during and after his rule.

9.1. Manetho's Accounts

The ancient Egyptian historian Manetho, writing over two millennia after Nynetjer's reign, refers to him as Binôthrís. Manetho's accounts are notable for a specific claim about Nynetjer's time: that "women received the right to gain royal dignity," meaning they were allowed to rule as a king. Egyptologists, such as Walter Bryan Emery, interpret this statement not as a direct change during Nynetjer's reign, but perhaps as an acknowledgment or historical reference to earlier powerful queens, like Meritneith and Neithhotep from the early First Dynasty of Egypt, who are believed to have held the throne for several years when their sons were too young to rule. This suggests a legacy of female influence in royal authority that was perhaps formally recognized or alluded to during Nynetjer's period, rather than a radical new policy.

9.2. Governing Philosophy

Nynetjer's governing philosophy can be inferred from his significant administrative reforms and the various theories surrounding the potential division of the state towards the end of his rule. His implementation of innovations, such as the formalized "Following of Horus" census for taxation and resource management, the establishment of new state institutions, and possibly an office for food management, indicates a strong emphasis on centralized control and efficient resource allocation. These reforms were crucial for the nascent Egyptian state, especially for funding monumental projects like royal tombs and ensuring the king's provisions in the afterlife. His approach appears to have been aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of kingship and ensuring the continued collection of commodities necessary to support a growing civil service and elaborate royal mortuary complexes.

The theories regarding the state's division-whether due to an overly complex administration (as suggested by Helck and others) or an economic crisis like famine (as proposed by Bell, though later refuted)-suggest that Nynetjer, or his immediate successors, faced profound challenges in maintaining the unity and stability of Egypt. If Nynetjer indeed chose to divide the realm, it would imply a radical, pragmatic approach to state management, prioritizing governance efficiency or addressing existential threats to the populace, even at the cost of political unity. This indicates a pharaoh grappling with the practicalities of governing a vast and increasingly complex kingdom, making decisions with potentially long-lasting social and political implications for the Egyptian state.

10. Assessment and Legacy

Nynetjer's reign is a pivotal period in early Egyptian history, leaving a substantial archaeological footprint and sparking enduring historical debates.

10.1. Archaeological Significance

Nynetjer stands out as the best-attested ruler of the entire Second Dynasty, a testament to the abundance of archaeological evidence associated with his reign. His name appears on numerous stone vessels and clay sealings found in his extensive tomb at Saqqara, as well as in other significant sites like Abydos and beneath Djoser's pyramid. The discovery and ongoing excavation of his monumental tomb, "Gallery Tomb B," have provided unparalleled insights into royal mortuary architecture, construction techniques, and funerary practices of the Early Dynastic Period. The wealth of burial goods, including hundreds of wine jars and a large collection of stone tools, offers a rare glimpse into the economy, ceremonial practices, and daily life of the ancient Egyptian court. The architectural similarities of his tomb to those of his predecessors also illuminate the evolution of royal burial complexes.

10.2. Historical Interpretations and Debates

Despite the wealth of archaeological data, Nynetjer's reign remains a subject of intense historical interpretation and debate, particularly concerning its conclusion. The conflicting accounts and archaeological clues about the end of his rule have led scholars to propose various theories, including political instability, religious and regional conflicts between Upper and Lower Egypt, or a deliberate administrative decision to divide the state. The economic collapse theory, based on a possible famine, exemplifies the dynamic nature of historical research, as it was later largely refuted by new interpretations of data from the Nile flood records. These ongoing debates underscore the complexities of reconstructing early dynastic history from fragmented evidence and highlight the multifaceted challenges faced by early Egyptian pharaohs in maintaining state unity and stability.

10.3. Influence on Later Periods

Nynetjer's administrative innovations left a lasting impact on subsequent periods of Egyptian history. The formalization and expansion of the "Following of Horus" census, transforming it into a crucial tool for taxation and resource management, laid fundamental groundwork for later state administration. While the specific name "Following of Horus" eventually disappeared, the underlying system of regular, comprehensive censuses, including later additions like cattle counts, became a cornerstone of Egyptian governance and economic control in the Old Kingdom and beyond.

In terms of religious developments, the increasing emphasis on sun worship and the cult of Ra during Nynetjer's reign foreshadowed Ra's eventual ascension to one of the most prominent positions in the Egyptian pantheon. This period marked a crucial step in the theological evolution that would profoundly influence state religion and royal ideology in later dynasties.

Architecturally, Nynetjer's tomb, with its extensive subterranean layout, numerous storage rooms, and its conceptualization as a locus for renewal rituals, significantly advanced royal mortuary architecture. Its design likely served as an influential precedent for the grander royal tomb complexes of the Third Dynasty, such as Djoser's Step Pyramid, which continued to integrate large storage capacities and elaborate underground structures. These advancements in statecraft, religion, and monumental architecture collectively attest to Nynetjer's enduring legacy on Egyptian civilization.

11. Commemoration and Memorials

Nynetjer is primarily commemorated through the extensive archaeological record of his reign, particularly his monumental tomb at Saqqara, known as Gallery Tomb B. This subterranean complex, with its intricate design and numerous chambers, stands as a direct and enduring memorial to his rule.

The vast quantity of artifacts, inscriptions on stone vessels, and clay sealings bearing his name, discovered both within his tomb and at other significant sites like Abydos and beneath Djoser's pyramid, serve as continuous attestations of his historical presence. These archaeological findings, meticulously studied by generations of Egyptologists, collectively form a comprehensive archive that details the administrative, religious, and funerary practices of the Early Dynastic Period. Through these physical remains, Nynetjer's reign and its contributions to the development of early Egyptian civilization are preserved and remembered.

12. Related Topics

- Second Dynasty of Egypt

- Pharaoh

- Early Dynastic Period (Egypt)

- Palermo Stone

- Abydos King List

- Turin King List

- Saqqara King List

- Saqqara

- Raneb

- Hotepsekhemwy

- Djoser

- Khasekhemwy

- Peribsen

- Senedj

- Manetho

- Ancient Egypt