1. Early Life

1.1. Early Life and Education

Maury Wills was born on October 2, 1932, in Washington, D.C., as the seventh of thirteen children to Guy and Mabel Wills. His parents, both originally from Maryland, played significant roles in his upbringing. His father, born in 1900, worked as a machinist at the Washington Navy Yard and also served as a part-time Baptist minister. His mother, born in 1902, was employed as an elevator operator.

Wills began playing semi-professional baseball at the age of 14. During his time at Cardozo Senior High School, he distinguished himself as a multi-sport athlete, excelling in baseball, basketball, and football. He earned All-City honors in each of these sports during his sophomore, junior, and senior years. On the baseball team, Wills showcased his versatility by playing both third base and pitching.

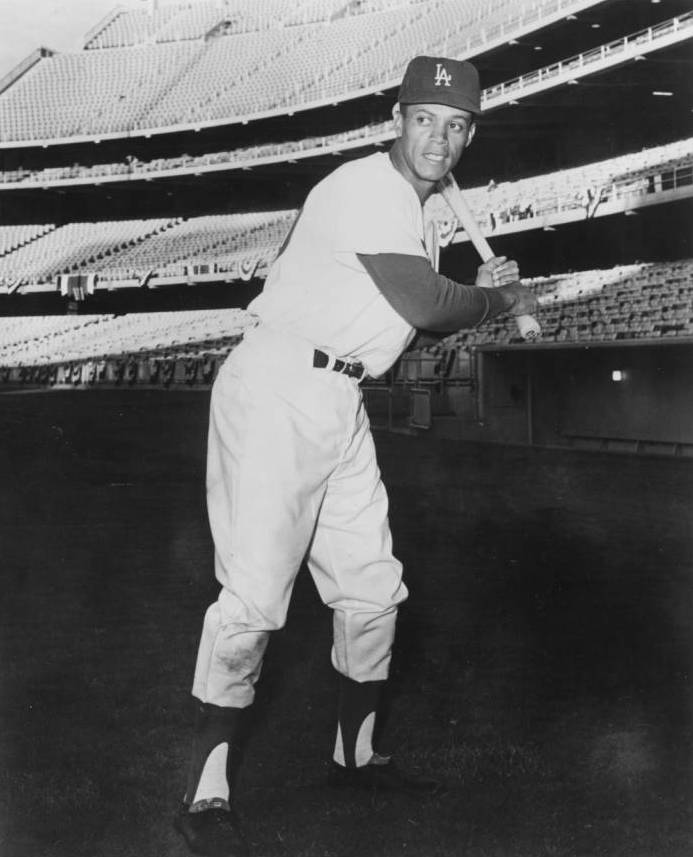

2. Professional Playing Career

Maury Wills' professional baseball journey spanned over two decades, beginning in the minor leagues before his breakthrough with the Los Angeles Dodgers, and later playing for the Pittsburgh Pirates and Montreal Expos.

2.1. Minor Leagues and Early Career

After graduating from high school, Wills signed with the then-Brooklyn Dodgers in 1950. He spent eight years developing his skills within the team's minor league system. Despite his efforts, opportunities for promotion to the MLB were limited, partly due to the presence of renowned shortstop Pee Wee Reese, who would later be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame and retired in 1958.

In 1956, Wills was briefly transferred to a minor league affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds, and subsequently to a minor league team under the Detroit Tigers. However, neither of these moves led to an MLB call-up. Before the 1959 season, the Detroit Tigers purchased his contract for 35.00 K USD, but they returned him to the Dodgers after spring training, reportedly believing he was not worth the salary. Wills rejoined the Dodgers, who had by then relocated to Los Angeles. He made his MLB debut on June 6, 1959, at the age of 26 years and 8 months. In his rookie season, he played in 83 games, batting .260 with 7 RBI. He also participated in all six games of the 1959 World Series against the Chicago White Sox, hitting 5-for-20 with one stolen base and two runs, contributing to the Dodgers' World Series victory in his first MLB season.

2.2. Los Angeles Dodgers (First Stint)

Following Pee Wee Reese's retirement after the 1958 season, the Dodgers initially started the 1959 season with Bob Lillis at shortstop, who struggled, leading to Don Zimmer taking over the position. When Zimmer broke his toe in June, Wills was called up from the minor leagues, marking his breakthrough into the Major Leagues.

In 1960, after the Dodgers traded Zimmer, Wills became the regular shortstop. In his first full season, he batted .295 with 27 RBI and led the league with 50 stolen bases in 148 games. This achievement made him the first National League player to steal 50 bases since Max Carey stole 51 in 1923. Wills's impact on defense was also recognized early, as he earned his first Gold Glove Award in 1961.

His most remarkable season came in 1962, when he set a new MLB stolen base record with 104 steals, surpassing Ty Cobb's modern era mark of 96 set in 1915. He was caught stealing only 13 times that year, achieving an 89% success rate. Wills's 104 stolen bases were more than any entire team in the league, with the Washington Senators leading teams with 99. He finished the season batting .299 with six home runs and 48 RBI, and also led the NL with 10 triples and 179 singles. His outstanding performance earned him the NL Most Valuable Player Award over Willie Mays, with teammate Tommy Davis finishing third. That same year, Wills was also named the first ever MLB All-Star Game Most Valuable Player. He continued to be recognized for his defensive prowess, winning his second consecutive Gold Glove in 1962.

In a unique historical note, Wills played a full 162-game schedule in 1962, plus all three games of the best-of-three regular season playoff series against the San Francisco Giants, totaling 165 games played. This remains an MLB record for the most games played in a single season. His 104 steals stood as a major league record until Lou Brock stole 118 in 1974. During the latter part of the 1962 season, Giants Manager Alvin Dark controversially ordered grounds crews to water down the base paths to create mud, an attempt to hinder Wills's base-stealing efforts.

Wills continued to be a key player for the Dodgers, contributing to their success in the 1963 World Series, where they swept the New York Yankees. He batted 2-for-16 (.133) with one stolen base in that series. In the hard-fought 1965 World Series, Wills played in all seven games, going 11-for-30 (.367) with three runs and three stolen bases, securing his third and final World Series title.

In 1966, Wills's stolen base total dropped to 38, and he was caught stealing 24 times, ending his streak of six consecutive stolen base titles. In the 1966 World Series, where the Dodgers were swept in four games, he batted 1-for-13 (.077) with one stolen base.

2.3. Pittsburgh Pirates

After the 1966 season, the Dodgers embarked on a postseason exhibition tour of Japan. Wills, who was dealing with knee issues and felt unable to perform, left the tour early and returned home. This departure was perceived as abandonment and disloyalty by Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley, who was already frustrated by the recent retirement of star pitcher Sandy Koufax. As a result, Wills was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Bob Bailey and Gene Michael.

In his first season with the Pirates in 1967, Wills played in 149 games, recording 186 hits, 29 stolen bases (his lowest since 1961), three home runs, 45 RBI, and a .302 batting average. The following season, 1968, he played in 153 games, accumulating 174 hits, 31 RBI, and 52 stolen bases, though he was caught stealing 21 times, with a .278 batting average.

2.4. Montreal Expos

On October 14, 1968, the Montreal Expos, an expansion team, selected Wills as their 21st pick in the expansion draft. He batted leadoff for the Expos in their inaugural game on April 8, 1969, going 3-for-6 with one RBI and one stolen base in an 11-10 victory. Wills played only 47 games for the Expos, recording 42 hits, 8 RBI, and 15 stolen bases with a .222 batting average.

His time in Montreal was marked by controversy. On May 19, an altercation with Montreal Gazette reporter Ted Blackman made headlines when Wills struck Blackman in the mouth, reportedly due to his displeasure with Blackman's reporting. Later that month, Wills's perceived loose play led to boos from Montreal fans. Unhappy with the situation, Wills briefly retired on June 3 but returned to the Expos just 48 hours later.

2.5. Los Angeles Dodgers (Second Stint)

On June 11, 1969, the Expos traded Wills to the Dodgers, along with Manny Mota, in exchange for Ron Fairly and Paul Popovich. In 104 games during his second stint with Los Angeles that season, he batted .297 with four home runS and 39 RBI, while stealing 25 bases. His performance earned him an 11th-place finish in the NL MVP voting.

In 1970, Wills played in 132 games, collecting 141 hits, 34 RBI, and 28 stolen bases, maintaining a .270 batting average. The 1971 season saw him play in 149 games, with 169 hits, three home runS, 44 RBI, and 15 stolen bases, batting .281. This strong showing resulted in a sixth-place finish in the NL MVP voting.

However, Wills struggled with his reflexes and timing in 1972, partly due to his failure to work out during the 1972 Major League Baseball strike. After a particularly difficult game against the Expos where he struggled against Carl Morton, Wills acknowledged to manager Walter Alston, "He's certainly justified if he takes me out." Alston subsequently replaced Wills in the lineup with Bill Russell on April 29, and Wills spent the remainder of the season as a reserve player, with Russell holding the starting shortstop position for several years thereafter.

In his final MLB season in 1972, Wills played 71 games, recording 17 hits, 4 RBI, and one stolen base, with a .129 batting average. His last MLB appearance was on October 4, 1972, when he entered as a pinch runner for Ron Cey in the top of the ninth inning, scoring a run on a home run by Steve Yeager. He also played third base in the bottom of the ninth. Wills was officially released by the Dodgers on October 24, 1972.

After his retirement, Wills was considered for a player-manager or player-coach role with the Nankai Hawks in Japan. However, the team's president, Shigeru Niiyama, preferred him as a coach-only due to his age, and the deal ultimately did not materialize.

3. Stolen Base Prowess and Records

Maury Wills revolutionized the perception and execution of the stolen base, transforming it into a potent offensive weapon and setting multiple records that left a lasting impact on baseball strategy.

3.1. Record-Breaking Seasons

In 1962, Wills set a new MLB record by stealing 104 bases, surpassing the previous modern era mark of 96 set by Ty Cobb in 1915. Notably, Wills's individual stolen base total that year exceeded the total stolen bases of any team in the league, with the Washington Senators having the highest team total at 99. Despite his aggressive base running, he was caught stealing only 13 times, demonstrating remarkable efficiency.

A unique record Wills holds from his 1962 season is playing 165 games in a single season. This was possible because the National League had expanded its regular season schedule to 162 games, and the Dodgers, tied for first place with the San Francisco Giants, played an additional three-game playoff series to determine the league champion. Wills participated in every one of these games, establishing a record that still stands for the most games played in a single MLB season. His 104 stolen bases remained the major league record until Lou Brock stole 118 in 1974.

It is worth noting that MLB Commissioner Ford Frick ruled that Wills's 104-steal season and Cobb's 96-steal season of 1915 were separate records. This decision was made because Wills's 97th stolen base occurred after the Dodgers had completed their 154th game, reflecting the league's expansion to a 162-game schedule. This "asterisk" distinction was similar to a ruling made the previous year regarding Roger Maris's single-season home run record. However, this distinction became less significant when Lou Brock broke both records in 1974 by stealing his 97th base before his St. Louis Cardinals completed their 154th game.

3.2. Impact on Base Stealing Strategy

Alongside Chicago White Sox shortstop Luis Aparicio, who consistently led the American League in stolen bases, Maury Wills brought a new level of prominence to the tactic of base stealing. Wills is credited with almost single-handedly shifting baseball's focus from power-hitting sluggers to recognizing pure speed as a serious offensive and defensive asset. His style of play was particularly crucial for the Dodgers, who relied heavily on pitching and defense, using Wills's speed to compensate for a relative lack of productive hitters.

Wills was a constant threat on base, creating a significant distraction for opposing pitchers even when he wasn't attempting to steal. Fans at Dodger Stadium would often chant, "Go! Go! Go, Maury, Go!" whenever he reached base, highlighting the excitement he generated. While not necessarily the fastest runner in the major leagues, Wills possessed an exceptional ability to accelerate quickly. He was also known for his meticulous study of pitchers, observing their pick-off moves relentlessly, even when not on base. His fierce competitiveness meant that if he was driven back to the bag, he became even more determined to steal. A notable example of this occurred against New York Mets pitcher Roger Craig, where Wills drew twelve consecutive throws from Craig to the first baseman before successfully stealing second base on Craig's next pitch to the plate. Wills's technique for starting a steal was known as the cross-over step.

Following his record-breaking 1962 season, Wills's stolen base totals saw a decline, with 40 stolen bases in 1963 and 53 in 1964. In July 1965, he was ahead of his 1962 pace, but at age 32, he began to slow down in the second half of the season. The physical toll of sliding led him to bandage his legs before every game. He finished the 1965 season with 94 stolen bases.

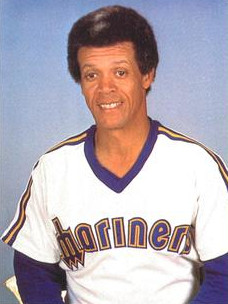

4. Managerial and Coaching Career

After his playing career, Maury Wills transitioned into various roles within baseball, including broadcasting, managing, and coaching, where he continued to influence the game, particularly in the art of base stealing.

From 1973 through 1977, Wills served as a baseball analyst for NBC. He also gained managerial experience in the Mexican Pacific League, a winter league, for four seasons. During his tenure, he led the Naranjeros de Hermosillo to the league championship in the 1970-71 season. Wills publicly expressed his belief that he was qualified to manage a big-league club, even claiming in his book, How To Steal A Pennant, that he could transform any last-place team into champions within four years. Although the San Francisco Giants reportedly offered him a one-year deal, Wills declined.

In August 1980, Wills was named the manager of the Seattle Mariners, replacing Darrell Johnson. However, his managerial tenure was marked by a series of gaffes. He was known for calling for relief pitchers when no one was warming up in the bullpen, causing a 10-minute delay in one game while searching for a pinch-hitter, and even leaving a spring training game in the sixth inning to fly to California.

A notable incident occurred on April 25, 1981, when Wills ordered the Mariners' grounds crew to extend the batter's boxes by one foot towards the mound, after receiving complaints that Tom Paciorek was batting outside the regulation box. Oakland Athletics manager Billy Martin noticed the alteration and alerted plate umpire Bill Kunkel. Under questioning, the Mariners' head groundskeeper admitted Wills had ordered the change. Wills claimed he was trying to help his players stay within the box, but Martin suspected he was attempting to give his players an unfair advantage, especially against the large number of breaking ball pitchers on the A's staff. The American League suspended Wills for two games and fined him 500 USD. American League umpiring supervisor Dick Butler likened Wills's actions to reducing the distance between bases.

After leading Seattle to a 20-38 record to conclude the 1980 season, new owner George Argyros fired Wills on May 6, 1981, with the Mariners holding a 6-18 record and deep in last place. His career managerial record stood at 26-56, resulting in a .317 winning percentage, one of the lowest ever for a non-interim manager.

Despite his struggles as a manager, Wills's coaching had a positive impact on individual players. Julio Cruz, an accomplished base stealer himself, credited Wills with teaching him how to steal second base against a left-handed pitcher. Similarly, Dave Roberts acknowledged Wills's coaching for his ability to steal under pressure, particularly his crucial stolen base in Game 4 of the 2004 American League Championship Series. Roberts recalled Wills's advice: "DR, one of these days you're going to have to steal an important base when everyone in the ballpark knows you're gonna steal, but you've got to steal that base and you can't be afraid to steal that base."

Wills also served as a coach for a team from 1996 to 1997 and worked as a radio color commentator for the Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks on KNFL until 2017. He resumed making appearances with the Dodgers in 2000, serving as a guest instructor in spring training until 2016. He was also invited as a temporary coach for the Hankyu Braves in Japan starting in 1978, and there were discussions for him to become a formal coach, though this never materialized.

5. Post-Playing Career and Entertainment

Throughout much of his major league playing career, Maury Wills supplemented his baseball income during the off-season by actively pursuing a career in entertainment. He performed extensively as a vocalist and instrumentalist, showcasing his talents on the banjo, guitar, and ukulele. His performances included occasional television appearances and frequent engagements in nightclubs.

Wills also recorded at least two musical records during this period: one released under his own name, and another where he was featured as a vocalist with jazz legend Lionel Hampton. From October 24, 1968, for approximately two years, Wills was the co-owner, operator, and featured performer of a nightclub in Pittsburgh's Golden Triangle called "The Stolen Base" (also known as Maury Wills' Stolen Base). The establishment offered a unique blend of "banjos, draft beer and baseball."

While Wills himself acknowledged he wasn't a "consummate virtuoso," describing his musical ability as "good; not great, maybe, but good," his proficiency on the banjo was formally recognized. In December 1962, the president of the Los Angeles Local 47 of the American Federation of Musicians waived the remainder of Wills's membership entrance exam after hearing him play the banjo for only a few minutes. More than five years later, trumpeter Charlie Teagarden presented Wills with an honorary lifetime membership on behalf of the musicians union, specifically citing "Maury's banjo-playing ability."

Beyond music, Wills ventured into acting, appearing in an episode of the popular television series Get Smart titled "Apes of Wrath" (season 5, episode 10) in 1969. In 1965, he also contributed two songs, "Dodger Stadium" (with teammate Willie Davis and comedian Stubby Kaye) and "Somebody's Keeping Score," to the album The Sound Of The Dodgers.

6. Personal Life

Maury Wills's personal life included family relationships, a notable public relationship, and a significant struggle with substance abuse that he later overcame.

6.1. Family and Relationships

Maury Wills was the father of former major league baseball player Bump Wills, who played for the Texas Rangers and Chicago Cubs for six seasons, accumulating 196 career stolen bases. A "salacious anecdote" in the elder Wills's 1992 autobiography, On the Run: The Never Dull and Often Shocking Life of Maury Wills, caused a falling out between father and son, though they occasionally spoke as of 2004.

In his autobiography, Wills also discussed a love affair with actress Doris Day, a claim that Day had previously denied in her own 1976 autobiography, Doris Day: Her Own Story. Wills later married Angela George, who played a crucial role in his recovery from substance abuse.

6.2. Substance Abuse and Recovery

Wills struggled with alcohol and cocaine dependency until 1989. In his autobiography, he revealed that he spent over 1.00 M USD of his own money on cocaine over a period of three and a half years. In December 1983, Wills was arrested for cocaine possession after his former girlfriend, Judy Aldrich, reported her car stolen. During a search of the vehicle, police found a vial allegedly containing 0.0 oz (0.06 g) of cocaine and a water pipe. The charge was dismissed three months later due to insufficient evidence.

The Los Angeles Dodgers organization offered to pay for a drug treatment program for Wills, but he left the program and continued to use drugs. His journey toward recovery began when he started a relationship with Angela George, who encouraged him to embark on a vitamin therapy program. Their relationship eventually led to their marriage.

7. Awards and Honors

Maury Wills received numerous awards and honors throughout his illustrious playing career and in recognition of his contributions to baseball and his community.

7.1. Playing Awards

- National League Most Valuable Player (MVP): 1962

- Gold Glove Award (Shortstop): 1961, 1962

- MLB All-Star Game MVP: 1962 (he was the first recipient of this award)

- National League Stolen Base Leader: 6 times (1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965)

- MLB All-Star Game selection: 5 times (participated in 7 All-Star Games, as two games were played in both 1961 and 1962)

- The Sporting News MLB Player of the Year Award: 1962 (shared with Don Drysdale)

7.2. Other Honors

- Hickok Belt Award: 1962. Following this award, Wills faced a tax case where the Commissioner of Internal Revenue determined deficiencies in his reported income and awards deductions. The United States Tax Court supported the Commissioner, and the decision was affirmed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

- The Baseball Reliquary's Shrine of the Eternals: Inducted in the class of 2011.

- "Legends of Dodger Baseball": Named in 2022, recognizing his significant contributions to the Los Angeles Dodgers organization.

- Maury Wills Field: In 2009, Washington, D.C. and Cardozo Senior High School honored Wills by renaming the former Banneker Recreation Field as Maury Wills Field. The field underwent complete renovation and serves as Cardozo's home baseball diamond.

- Maury Wills Museum: A museum dedicated to his career opened in 2001 at Newman Outdoor Field in Fargo, North Dakota, home of the Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks. The museum closed in 2017 upon his retirement from broadcasting.

8. Hall of Fame Candidacy

Maury Wills was a candidate for induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame for many years, but despite his significant achievements, he was never elected.

As a candidate on the BBWAA ballot, Wills was eligible for fifteen years, from 1978 to 1992. However, he consistently fell short of the required 75% of the vote, never receiving more than 40.6%. His vote totals notably declined by half after 1982, and his arrest for cocaine possession in 1983 likely contributed to his numbers never recovering.

In 2014, Wills appeared for the first time as a candidate on the Golden Era Committee election ballot for the 2015 Hall of Fame induction. Election by this committee required twelve votes. Wills missed induction by three votes, and ultimately, none of the candidates on that ballot were elected. The Golden Era Committee was subsequently replaced in 2016 by four new committees, including the Golden Days Committee, which covers the period from 1950 to 1969. Wills was on the 2022 ballot for the Golden Days Committee but again did not receive enough votes for induction.

9. Legacy and Evaluation

Maury Wills's legacy in baseball is primarily defined by his revolutionary approach to the stolen base and his instrumental role in the Los Angeles Dodgers' success during the 1960s. He is widely credited with reviving the stolen base as a strategic offensive weapon, transforming it from an individual feat into a team-oriented tactic that could disrupt opposing pitchers and defenses. His meticulous study of pitchers' pick-off moves, combined with his exceptional acceleration and fierce competitiveness, made him a constant threat on the basepaths.

His record-breaking 1962 season, where he stole 104 bases and played an unprecedented 165 games, cemented his place in baseball history as an innovator. Wills's influence extended beyond his playing days; he inspired and coached future generations of base stealers. Notable players like Julio Cruz and Dave Roberts have publicly credited Wills with teaching them the nuances of base stealing, particularly in high-pressure situations. His impact on Roberts's crucial stolen base in Game 4 of the 2004 ALCS highlights the lasting effect of Wills's teachings.

While his managerial career was brief and challenging, his contributions as a player and his dedication to teaching the art of base stealing underscore his enduring legacy as a significant figure in the evolution of baseball strategy.

10. Death

Maury Wills died at his home in Sedona, Arizona, on September 19, 2022, at the age of 89. His passing occurred just two weeks before his 90th birthday.