1. Early Life and Background

This section covers Maurice Denis's upbringing, education, and the formative artistic influences that shaped his early career.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Maurice Denis was born on November 25, 1870, in Granville, Manche, a coastal town in the Normandy region of France. His father came from modest peasant origins and, after serving four years in the army, worked at a railroad station. His mother, the daughter of a miller, was a seamstress. After their marriage in 1865, the family relocated to Saint-Germain-en-Laye in the Paris suburbs, where his father was employed in the offices of the Western Railroads administration in Paris.

As an only child, Denis developed early passions for both religion and art. He began keeping a journal at the age of thirteen in 1884. In 1885, he recorded his admiration for the colors, candlelight, and incense of the ceremonies at the local church, indicating a deep spiritual inclination from a young age. He frequently visited the Louvre Museum, where he particularly admired the works of Fra Angelico, Raphael, and Botticelli. At fifteen, he articulated his artistic and spiritual aspirations in his journal, writing, "Yes, I must become a Christian painter, that I celebrate all the miracles of Christianity, I feel that is what is needed."

Denis was accepted into the prestigious Lycée Condorcet in Paris, where he excelled in philosophy. However, he decided to leave the school at the end of 1887. In 1888, he enrolled in Académie Julian to prepare for the entrance examination to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. At Académie Julian, he studied under the painter and theorist Jules Joseph Lefebvre. He successfully passed the entrance examination for the École des Beaux-Arts in July 1888 and, in November of the same year, earned his baccalaureate in philosophy.

1.2. Early Artistic Influences

Denis's early artistic vision was shaped by a diverse range of inspirations, reflecting his blend of traditional reverence and modern innovation. His frequent visits to the Louvre instilled in him a deep admiration for the Italian Renaissance masters, particularly Fra Angelico, Raphael, and Botticelli, whose works he studied meticulously. In 1887, he discovered a new source of inspiration in the works of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, an artist known for his monumental, symbolic murals, which resonated with Denis's burgeoning interest in idealism and decorative art.

While initially drawn to the Neo-Impressionist style of Georges Seurat, Denis ultimately rejected it, finding it too scientific and lacking in emotional depth. A pivotal moment occurred in 1889 when Denis was captivated by an exhibition of works by Paul Gauguin and his associates at the Cafe Volponi, near the Paris Universal Exposition. Recalling this experience, Denis noted, "What amazement, followed by what a revelation! In place of windows opening on nature, like the impressionists, these were surfaces which were solidly decorative, powerfully colorful, bordered with brutal strokes, partitioned." Gauguin's work had an immediate and profound effect on Denis, influencing his adoption of brightly colored forms and distinct outlines, as seen in his October 1890 work Taches du soleil sur la terrace, and later in Solitude du Christ (1918).

Another significant influence on Denis during this period was Japanism, the interest of French artists in Japanese art. This interest, which had begun in the 1850s and was renewed by displays at the Paris Universal Exposition (1855), was further revived in 1890 by a major retrospective of Japanese prints at the École des Beaux-Arts. Even before 1890, Denis had been studying illustrations from the catalog Japan Artistique, published by Siegfried Bing. In November 1888, he expressed his desire to move from "Giving color to (Puvis de Chavannes)" to "making a blend with Japan." His paintings in the Japanese style often featured a wide format and highly stylized compositions and decorations, resembling Japanese screens.

2. Art Career and Development

This section traces Maurice Denis's artistic evolution, from his involvement with Les Nabis and Symbolism to his theoretical contributions, personal life influences, and significant works in Neo-Classicism, decorative arts, religious art, and civic murals.

2.1. Formation and Philosophy of Les Nabis

While studying at the Académie Julian, Maurice Denis met fellow students Paul Sérusier and Pierre Bonnard, with whom he shared similar artistic ideas. Through Bonnard, he was introduced to other artists, including Édouard Vuillard, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, and Hermann-Paul. In 1890, this group formed a collective known as Les Nabis, a name derived from the Hebrew word "Nabi," meaning "Prophet," signifying their ambition to forge new forms of artistic expression.

The Nabis' philosophy, while diverse among its members, generally rejected naturalism and materialism in favor of a more idealistic and subjective approach to art. Denis, in particular, emerged as a key theorist and spokesperson for the movement. In 1909, he articulated their core belief: "Art is no longer a visual sensation that we gather, like a photograph, as it were, of nature. No, it is a creation of our spirit, for which nature is only the occasion." This emphasis on art as a spiritual creation, rather than a mere imitation of reality, underscored their departure from Impressionism and their embrace of subjective sensation and symbolic meaning.

Although the Nabis group began to drift apart by the end of the 1880s, their innovative ideas continued to influence the later works of both Bonnard and Vuillard, and even extended to non-Nabi painters such as Henri Matisse, demonstrating the lasting impact of their collective artistic exploration.

2.2. Symbolism and Japanism

Maurice Denis's artistic journey was deeply intertwined with the Symbolist movement, which gained significant traction in the early 1890s. The literary movement of Symbolism was formally launched by Jean Moréas in an article in Le Figaro in 1891. By March 1891, the critic George-Albert Dourer had already identified Denis as the leading example of "symbolism in painting" in an article for the Mercure-de-France, underscoring Denis's early and critical recognition within the movement. Denis's work attracted the attention of critics and important patrons, most notably Arthur Huc, the owner of the prominent newspaper La Dépêche de Toulouse, who organized his own art salons and acquired several of Denis's pieces.

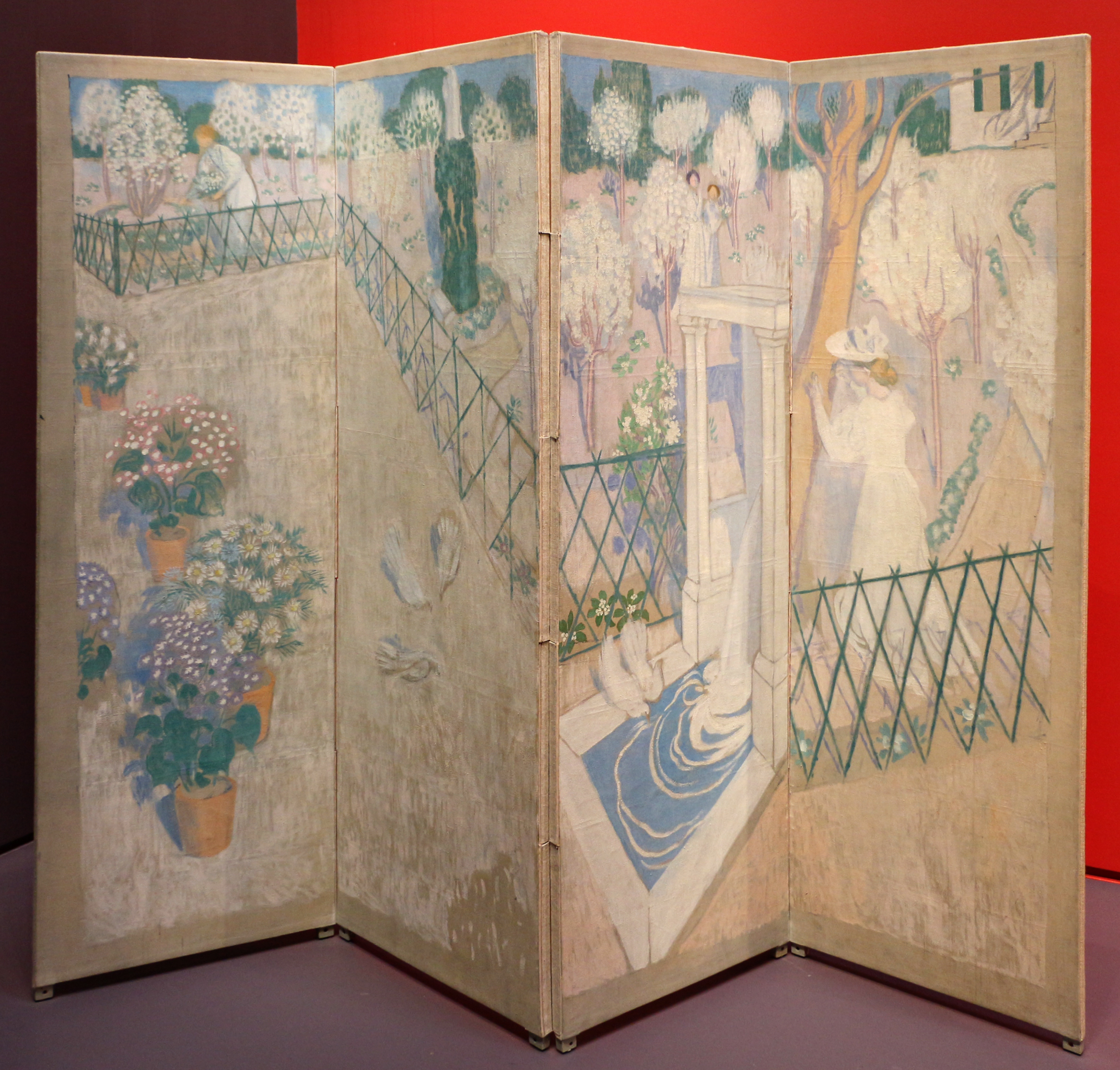

A significant influence on Denis's early Symbolist work was the art of Japan, which had captivated French artists since the 1850s. This interest was renewed by major exhibitions, including a significant retrospective of Japanese prints at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1890. Even before this, Denis had been studying illustrations from the catalog Japan Artistique, published by Siegfried Bing. In November 1888, he expressed to his friend Émile Bernard his desire to move from "giving color to (Puvis de Chavannes)" to "making a blend with Japan." His paintings inspired by Japanese aesthetics often featured a wide format, highly stylized compositions, and decorative qualities, reminiscent of Japanese screens, as exemplified by his work September Evening (1891). This integration of Japanese principles allowed Denis to infuse his Symbolist works with a distinct flatness and decorative emphasis, aligning with his theoretical assertion about the picture plane.

2.3. Artistic Theories and the Picture Plane

In August 1890, Maurice Denis consolidated his evolving artistic ideas into a seminal essay published in the review Art et Critique. This essay contained one of the most celebrated and influential opening lines in modern art theory: "Remember that a picture, before being a battle horse, a female nude or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order."

While the core idea-that a painting is fundamentally a colored surface-was not entirely new (it had been articulated by Hippolyte Taine in The Philosophy of Art), it was Denis's concise and forceful expression that captured the attention of artists and became a cornerstone of modernism. Denis was among the first artists to emphatically insist on the flatness of the picture plane, a concept that became a foundational starting point for modern artistic movements. However, Denis clarified that he did not intend for this statement to mean that the form of the painting was more important than its subject. He further elaborated, "The profoundness of our emotions comes from the sufficiency of these lines and these colors to explain themselves...everything is contained in the beauty of the work." In this essay, he termed his new artistic approach "neo-traditionalism," contrasting it with the "progressism" of the Neo-Impressionists led by Georges Seurat. With the publication of this article, Denis became the most recognized spokesperson for the philosophy of the Nabis, despite the group's internal diversity and varied opinions on art.

2.4. Marriage and Marthe Meurier

A significant personal event in Maurice Denis's life that profoundly impacted his art was his meeting with Marthe Meurier in October 1890. Their romance, meticulously documented in his journal, began in June 1891, culminating in their marriage on June 12, 1893. Marthe became an indispensable part of his artistic world, serving as his primary muse and appearing as a frequent subject in countless paintings and decorative works, such as painted fans. She was often depicted in an idealized form, symbolizing purity and love, embodying the spiritual and humanistic dimensions that Denis sought to express in his art.

From 1891 onwards, Marthe was the most frequent subject of his paintings, appearing in domestic scenes performing household tasks, taking naps, or at the dining table. She also featured prominently in his landscapes and in his most ambitious works of the period, such as The Muses series, which he began in 1893 and exhibited at the Salon of Independents. The French state acquired one of these paintings in 1899, marking his first official recognition.

Denis's interest in the connections between music and art grew throughout the 1890s, influenced by Marthe's piano playing. He painted her at the piano in 1890 and designed a flowing lithograph featuring Marthe for the cover of the sheet music for La Damoiselle élue by Claude Debussy. He also created another lithograph for the poem Pelléas et Mélisande by Maurice Maeterlinck, which Debussy later transformed into an opera. In 1894, he painted La Petit Air, inspired by the poem Princesse Maleine by Stéphane Mallarmé, a leading literary figure of Symbolism. In 1893, Denis collaborated with the writer André Gide on Le Voyage d'Urien, providing thirty lithographs that, rather than illustrating the text directly, approached the same themes from an artist's perspective, showcasing the synergy between art and literature.

Another significant theme Denis explored during this period was the relationship between sacred and profane love. In one painting, he depicted three female figures-two nude and one clothed-drawing inspiration from works like Le Concert Champêtre and L'Amour Sacré et L'Amour Profane by Titian and Déjeuner sur l'herbe by Édouard Manet. Set in his own garden with the viaduct of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in the background, the nude figures represented sacred love, while the clothed figure symbolized profane love. He later painted Marthe nude in the garden, a single figure embodying both sacred and profane love.

2.5. Neo-Classicism and Traditionalism

Maurice Denis's artistic direction took a significant turn towards Neo-Classicism following his first visit to Rome in January 1898. The works of Raphael and Michelangelo in the Vatican left a profound impression on him. This experience led him to write a lengthy essay, Les Arts a Rome, in which he declared that "the classical aesthetic offers us at the same time a method of thinking and a method of wanting to be, a moral and at the same time a psychology...The classical tradition as a whole, by the logic of the effort and the greatness of results, is in some way parallel with the religious tradition of humanity." This statement underscored his growing conviction in the enduring values of classical art and its spiritual resonance.

Upon his return to Paris, and coinciding with the deaths of the leading Symbolist figures Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes in the same year, Denis re-oriented his art towards Neo-Classicism, characterized by clearer lines and figures. He noted in his journal in March 1898 his aspiration to "Reconcile the employment of large-scale decorative means and the direct emotions of nature."

Denis was a great admirer of Paul Cézanne, whom he visited in 1896. He later wrote an article quoting Cézanne's famous comment: "I want to make of impressionism something solid and durable, like the art in museums." In the article, Denis hailed Cézanne as "the Poussin of impressionism" and credited him as the founder of modern Neo-Classicism. One of Denis's most important works from this period is Homage to Cézanne (1900), painted after Cézanne's death. The painting portrays Cézanne's friends, many of whom were former Nabis, dressed in black for mourning. From left to right, the figures include Odilon Redon, Édouard Vuillard, the critic André Mellerio, Ambroise Vollard, Denis himself, Paul Sérusier, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, Pierre Bonnard, and Denis's wife Marthe. Beyond its somber appearance, the painting conveys a deeper message: the artworks displayed behind the figures and on the easel represent the transition of modern art, from works by Gauguin and Renoir on the back wall to Cézanne's painting on the easel, illustrating, from Denis's perspective, the shift from Impressionism and Symbolism towards Neo-Classicism.

Denis was also affected by the political turmoils of his time, such as the Dreyfus affair (1894-1906), which deeply divided French society and the art world. While figures like Émile Zola and André Gide defended Dreyfus, Denis aligned with others like Auguste Rodin and Pierre-Auguste Renoir on the opposing side. Although he was in Rome during much of the affair, it did not significantly impact his friendship with Gide. More impactful for Denis was the French government's movement to reduce the power of the church, culminating in the official separation of church and state in 1905. In response, Denis joined the nationalist and pro-Catholic Action Française in 1904. He remained a member until 1927, when the group moved further to the extreme right and was formally condemned by the Vatican, leading to his departure.

2.6. Art Nouveau and Decorative Arts

In the mid-1890s, with the emergence of the Art Nouveau style in Brussels and Paris, Maurice Denis began to dedicate greater attention to the decorative arts. Despite this stylistic shift, his core themes of family and spirituality remained consistent. Many of his new decorative projects were commissioned by Samuel Bing, the influential art dealer whose gallery gave its name to the Art Nouveau movement.

His new ventures included designs for wallpapers, stained glass, tapestries, lampshades, screens, and fans. While he adopted the materials and worked within the aesthetic period of Art Nouveau, Denis maintained a distinctive style and thematic focus that remained uniquely his own.

One of his most significant decorative works was a series of painted panels for the office of Baron Cochin, collectively known as The Legend of St. Hubert, executed between 1895 and 1897. This series drew inspiration from diverse sources, including the Medici Chapel in Florence and the works of Nicolas Poussin, Eugène Delacroix, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. The panels celebrated themes of family and faith, with Cochin and his family appearing in one panel, and Denis's wife Anne in another. The Archbishop of Paris even celebrated a mass in the office, highlighting the work's spiritual significance, before the French government nationalized Cochin's residence and other church property in 1907. Denis also produced a small number of portraits, including an unusual depiction of Yvonne Lerolle (1897) that showed her in three different poses within the same picture.

2.7. Religious Art and Sacred Art Workshops

Maurice Denis maintained a profound and lifelong commitment to religious art, which became an increasingly central focus in the later period of his life and work, particularly in large-scale murals.

In 1914, Denis purchased a former 17th-century hospital in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, built under Louis XIV, which he renamed "The Priory." Between 1915 and 1928, with the assistance of architect Auguste Perret, he undertook the decoration of the building, especially its unfinished chapel. He filled it with his own designs of frescos, stained glass, statues, and furniture, transforming it into a holistic artistic and spiritual environment. In 1916, he declared his intention to pursue the "supreme goal of painting, which is the large-scale decorative mural," ultimately completing twenty murals between that year and his death in 1943.

Following World War I, on February 5, 1919, Denis co-founded the Ateliers d'Art Sacré (Workshops of Sacred Art) with George Desvallières. This initiative was part of a broader European movement aimed at reconciling the church with modern civilization and promoting a revival of religious art, particularly for churches devastated by the recent conflict. Denis articulated his artistic philosophy for the Ateliers, stating his opposition to academic art for sacrificing emotion to convention and artifice, and to realism for being "prose" when he desired "music." Above all, he sought beauty, which he considered an attribute of divinity.

The Ateliers contributed to the decoration of numerous churches. Notable religious works by Denis during this period include the decoration of the Église Notre-Dame du Raincy, an innovative reinforced concrete Art Deco church in the Paris suburbs designed by Auguste Perret, completed in 1924. The church's design, inspired by Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, maximized the effect of its stained glass. Denis collaborated with stained-glass artist Marguerite Huré, designing the figurative art in the center of each window while Huré created the abstract glass designs around them. Other major religious commissions included the chapel of Saint-Louis in Vincennes (1927), the windows of the chapel of La Clarté in Perros (1931), and the church of Thonon, his final project before his death in 1943.

The most important church decorated by the Ateliers d'Art Sacré was the Église du Saint-Esprit in Paris, completed in 1934. The church's interior murals and frescoes, painted by members of the Ateliers, depicted the history of the church militant and triumphant from the 2nd to the 20th century. To ensure unity, the architect imposed a standard height for all figures and red as the background color. Denis painted two of the major works within the church: the Altarpiece and another large work beside it. These murals were strongly influenced by the Renaissance art he had studied in Italy, particularly the work of Giotto and Michelangelo. In 1922, he wrote, "The sublime is to approach the subject or wall with an attitude that is grand, noble, and in no way petty," reflecting his commitment to monumental and spiritually uplifting religious art.

2.8. Book Design and Illustration

From 1899 to 1911, Maurice Denis was actively engaged in the graphic arts, showcasing his versatility beyond painting. For the publisher Ambroise Vollard, he created a set of twelve color lithographs titled Amour, which, while artistically successful, did not achieve commercial success.

He then returned to woodblock printing, producing a black-and-white series titled L'Imitation de Jesus-Christ in collaboration with the engraver Tony Beltrand, published in 1903. This was followed by illustrations for Sagesse by the poet Paul Verlaine, published in 1911. In 1911, Denis began work on illustrations for Fiorette by Saint Francis of Assisi. For this project, he embarked on a solitary bicycle journey through Umbria and Tuscany, making numerous drawings. The final work, published in 1913, was characterized by rich and colorful floral illustrations, reflecting his deep connection to nature and spirituality.

Denis also created highly decorative book designs and illustrations for other significant literary works, including Vita Nova by Dante (1907) and twenty-four illustrations for Eloa by Alfred de Vigny (1917). The latter work, created during the midst of World War I, was more somber than his earlier pieces, largely colored in pale blues and grays, reflecting the prevailing mood of the time.

2.9. Architectural Decoration and Civic Murals

In the later stages of his career, Maurice Denis received numerous prestigious commissions for architectural decoration and public murals, both in France and internationally, demonstrating his ability to adapt his distinctive style to large-scale, public projects.

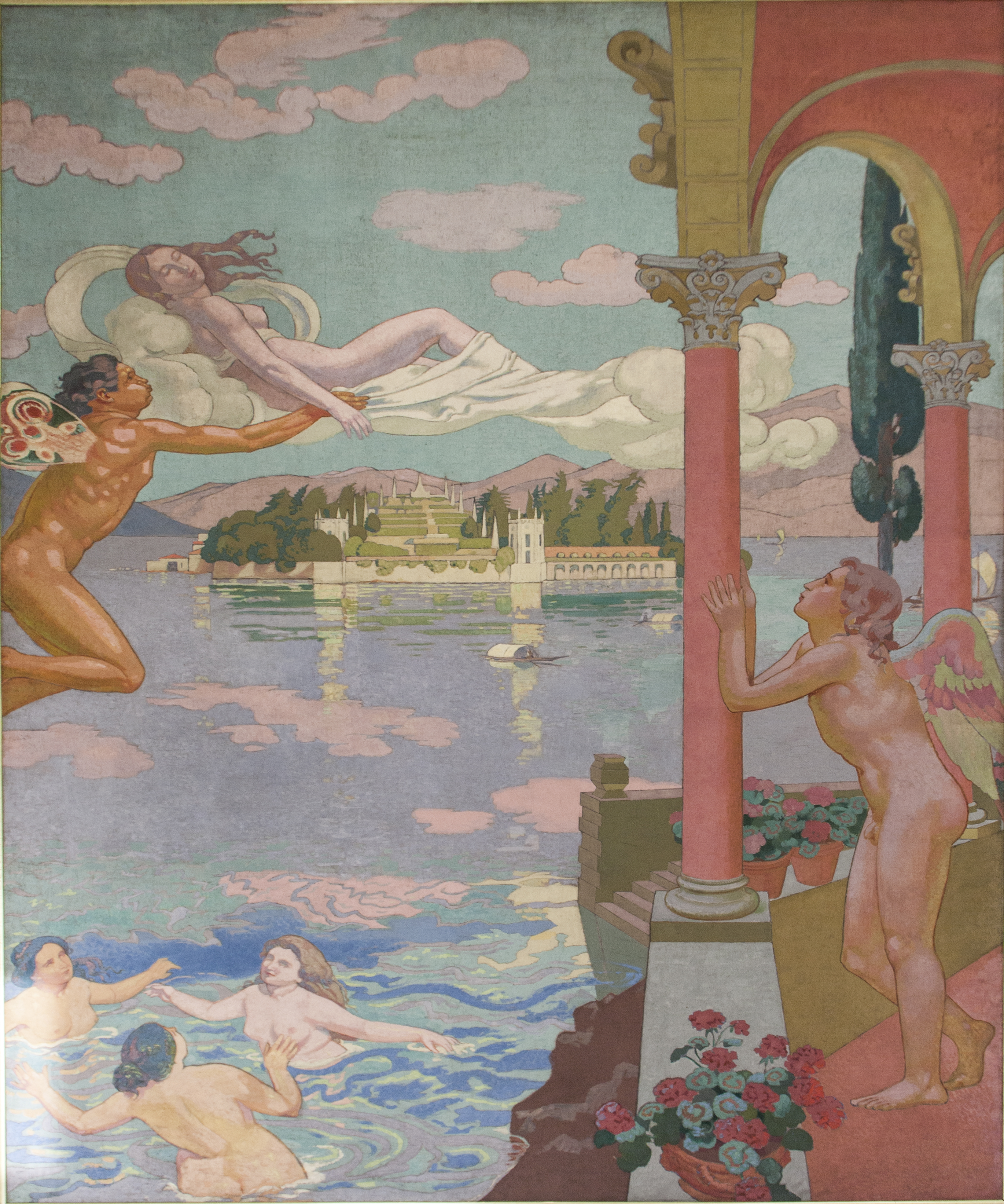

In 1908, he began work on an important decorative project for the Russian art patron Ivan Morozov, a significant collector who had patronized artists like Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir and owned Vincent van Gogh's The Night Cafe. Denis created a large mural panel titled The History of Psyche for the music room of Morozov's Moscow mansion, later adding additional panels to the design. The substantial fee from this project enabled him to purchase his seaside house in Brittany.

He then undertook an even more ambitious project: the decoration of the cupola for the new Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, designed by the architect Auguste Perret. This theater was a marvel of modern architecture, being the first major building in Paris constructed of reinforced concrete and considered a pioneering example of the Art Deco style. Despite the building's modern aesthetic, Denis's work for the cupola was purely neoclassical, with the theme of the history of music, featuring figures of Apollo and the Muses. Perret constructed a special studio for Denis to accommodate the immense scale of the work.

In the late 1920s and 1930s, Denis's prestige led to commissions for murals in important civic buildings. These included the ceiling over the stairway of the French Senate in the Luxembourg Palace and murals for the Hospice of Saint-Étienne, where he revisited the colorful and neoclassical themes of his earlier beach paintings. He was also commissioned to create two mural panels for the Palais de Chaillot, built for the 1937 Paris International Exposition. For this project, Denis invited several friends from his earlier career, including Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Ker-Xavier Roussel, to collaborate. The two panels celebrate sacred and profane music in a colorful neoclassical style, recalling his earlier decoration for the cupola of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The classical panel depicts an ancient celebration in the Boboli Gardens in Rome, which he had recently visited. These paintings remain visible today, though they have been somewhat altered by later renovations.

Denis also received two significant international commissions in his later years, both centered on his favored themes of Christian faith and humanism. In 1931, he created a mural for the Offices of the International Labor Bureau in Geneva, commissioned by the International Association of Christian Workers, on the theme "Christ preaching to the workers." In 1938, he completed a work for the new headquarters of the League of Nations on the theme of being armed for peace, depicting a figure of Orpheus taming the tiger of war, reflecting his commitment to social progress and peace through art.

2.10. Teaching and Theoretical Writings

Beginning in 1909, Maurice Denis took on a teaching role at the Académie Ranson in Paris, where his students included the notable artist Tamara de Lempicka. Lempicka later credited Denis with teaching her the craft technique of painting, despite her distinct Art Deco style. Beyond his teaching, Denis dedicated a significant portion of his time to theoretical writings, synthesizing his artistic journey and philosophical insights.

In 1909, he published Théories, a collection of articles he had written on art since 1890. This influential book, subtitled "From Symbolism and Gauguin towards a new classical order," described the trajectory of art from Gauguin to Matisse (whose work he disliked) and to Cézanne and Maillol. Théories was widely read, with three more editions published before 1920, solidifying Denis's reputation as a leading art theorist. The book included his 1906 essay "The Sun," in which he critiqued the decline of Impressionism, stating: "The common error of us all was to search above all for the light. It would have been better first to search for the Kingdom of God and his justice, that is to say for the expression of our spirit in beauty, and the rest would have arrived naturally." He also articulated his belief that "Art is the sanctification of the nature, of that nature found in everyone who is content to live."

Furthermore, Théories expounded his theory of creation, which posited that the source of art lay in the character and will of the painter: "That which creates a work of art is the power and the will of the artist." While his mature works encompassed landscapes and figure studies, particularly of mother and child, his primary interest remained the painting of religious subjects, such as "The dignity of labour," commissioned in 1931 by the International Federation of Christian Trade Unions to decorate the main staircase of the Centre William Rappard in Geneva.

3. Personal Life

Maurice Denis's personal life was deeply intertwined with his artistic output, particularly through his two marriages.

3.1. Family and Marriages

He married his first wife, Marthe Meurier, in 1893. Together, they had seven children, and Marthe became an enduring muse and frequent model for countless of Denis's works, embodying idealized forms of purity and love. Following her death in 1919, Denis painted a chapel dedicated to her memory, a testament to her profound influence on his life and art.

On February 22, 1922, Denis married Elisabeth Graterolleore, who had previously served as a model for one of the figures in the cupola of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. They had two children, Jean-Baptiste (born 1923) and Pauline (born 1925). Elisabeth also featured in several of Denis's paintings, sometimes depicted alongside Marthe, reflecting the continuity of his personal muses.

3.2. Religious and Social Engagement

Maurice Denis was a devout Catholic throughout his life, actively involved in the Tertiary, a lay religious order within the Roman Catholic Church. His deep faith profoundly influenced his artistic themes, leading him to dedicate a significant portion of his career to religious art and the revival of sacred art.

His social and political stances were complex and evolved over time. In 1904, Denis joined the nationalist and pro-Catholic Action Française movement. However, he distanced himself and left the group in 1927 when it moved further to the extreme right and was formally condemned by the Vatican. This decision highlights his moral compass and his willingness to disassociate from movements that diverged from his core values, even if he had initially found common ground with them. During World War II, Denis firmly rejected the collaborationist Vichy government, demonstrating a clear stance against authoritarianism and in favor of humanistic principles.

Maurice Denis died in Paris in November 1943 from injuries sustained in an automobile accident. The exact date of his death is variously listed as the 2nd, 3rd, or 13th of November.

4. Assessment and Legacy

This section evaluates Maurice Denis's lasting impact on modern art and examines the critical reception and historical re-evaluation of his work.

4.1. Impact on Modern Art

Maurice Denis's contributions were foundational to the development of modern art movements, particularly through his influential theoretical writings. His seminal 1890 essay, which famously asserted that a painting is "essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order," became a crucial starting point for modernism. This emphasis on the flatness of the picture plane and the autonomy of the artwork's formal elements profoundly influenced subsequent generations of artists.

His theories on color, form, and the subjective nature of artistic creation provided intellectual scaffolding for emerging styles. While he later diverged from the more radical directions of some avant-garde movements, his early insights are recognized as having contributed to the theoretical foundations of Cubism, Fauvism, and abstract art. He was considered part of the avant-garde of Paris artists until about 1906. However, in that year, Henri Matisse presented La Joie de Vivre, with its bright and clashing colors characteristic of Fauvism. In response, Denis increasingly turned toward mythology and what he termed "Christian humanism," leading to a series of neoclassical works depicting nudes at the beach or in bucolic settings, often based on mythological themes, such as Bacchus and Ariadne (1907) and Bathers at Perros Guirec (1912). These works, while distinct from Fauvism, still explored color and form in a manner that built upon modernist principles.

4.2. Critical Reception and Historical Evaluation

Maurice Denis's artistic achievements and theoretical impact have been subject to varied critical assessments throughout history. Initially, he gained significant recognition as a leading figure of Symbolism and a key theorist of the Nabis, with his 1890 essay being widely acclaimed as a foundational text for modern art. His early works, influenced by Gauguin and Japanese art, were seen as innovative and deeply expressive.

However, as the art world moved towards more radical forms of modernism like Fauvism and Cubism, Denis's shift towards Neo-Classicism and his unwavering commitment to religious themes sometimes led to his being perceived as less avant-garde by some contemporaries. His response to the emergence of Fauvism, turning towards mythological and "Christian humanism" themes in works like his beach pictures, demonstrated a continued exploration of form and color, even as his aesthetic diverged from the most cutting-edge trends. These works, often depicting happy families or nudes in bucolic settings, were an homage to the bathers of Raphael and classical Greek sculpture.

Denis was also affected by the political turmoils of his time, such as the Dreyfus affair (1894-1906), which divided French society and the art world. While he aligned with figures like Rodin and Renoir on one side of the affair, his friendship with André Gide, who defended Dreyfus, remained unaffected, indicating a nuanced personal approach to political divisions. More significant for him was the French government's move to reduce the power of the church, culminating in the official separation of church and state in 1905, which fueled his commitment to religious art.

In recent years, art historians have re-evaluated Denis's legacy, emphasizing his crucial role in bridging Impressionism with later modern movements through his theoretical insights and his significant contributions to decorative and sacred art. His dedication to integrating art with spiritual and humanistic values, as well as his later civic murals with social themes, are increasingly recognized as vital aspects of his enduring impact.

A notable aspect of his legacy also includes the restitution of looted art. In 2023, Denis's Stehender Knabe unter einem Baum, which had been listed on the German Lost Art Foundation website, was found and restituted to the family of Holocaust victim Marcel Monteux, from whom it had been looted during World War II.

5. Exhibitions

Significant exhibitions and retrospectives have been dedicated to Maurice Denis's work, highlighting his artistic evolution and influence:

- 1963**: From June 28 to September 29, an exhibition titled Paintings, water-colours, drawings, lithographs was held at the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi, with an introduction by Agnès Humbert.

- 1980**: The Maurice Denis Museum (Musée départemental Maurice Denis Le Prieuré) was opened in the artist's former home in the Parisian suburb of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, establishing a permanent space for his legacy.

- 1995**: A major retrospective exhibition took place at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, United Kingdom, offering a comprehensive overview of his work.

- 2007**: A similar significant exhibition was mounted at the Musée Des Beaux Arts de Montréal in Canada, marking the first major Denis show in North America.

Several of Maurice Denis's works are also held in Japanese collections, including:

- Mother and Child (1895) at the Uroko Museum.

- Hen and Girl (1890) at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.

- Chaste Spring (1899), on deposit at the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum.

- Procession of the Eucharist (1904), an oil on canvas measuring 59 in (149.9 cm) by 79 in (201 cm), at the Ise Cultural Foundation.

- Dancing Women (1905) at the National Museum of Western Art.

- Wave (1916) at the Ohara Museum of Art.

6. Quotations about Art

Maurice Denis's published writings and private journals offer extensive insight into his philosophy of art, which he developed throughout his lifetime:

- "Remember that a picture, before being a battle horse, a female nude or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order." (Art et Critique, August 1890)

- "Art remains a sure refuge, the hope of a reason for our life here, and this consoling thought that a little beauty is also found in our life, and that we are continuing the work of creation....the labor of art has merit; to inscribe the marvelous beauty of flowers, of the light, of the proportion of trees and the form of waves, and the perfection of face, to inscribe our poor and lamentable life of suffering, of hope and of thought." (Journal, March 24, 1895)

- "Decorative and edifying. That is what I want art to be before anything else." (Nouvelles Théories, 1922)

- "Painting is first of all the art of imitation, and not the servant of some imaginary 'purity'." (Nouvelles Théories, 1922)

- "Don't lose sight of the essential objectives of painting, which are expression, emotion, delectation; to understand the means, to paint decoratively, to exalt form and color." (Journal, 1930)