1. Early life and education

Mary Todd Lincoln's early life was shaped by her upbringing in a prominent and wealthy Kentucky family, where she received a comprehensive education that prepared her for social life and instilled in her an early interest in politics.

1.1. Birth and childhood

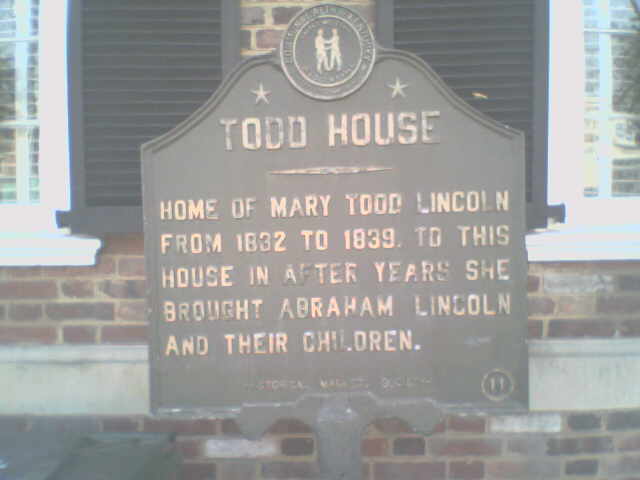

Mary Ann Todd was born on December 13, 1818, in Lexington, Kentucky, as the fourth of seven children to Robert Smith Todd, a banker, and Elizabeth "Eliza" (Parker) Todd. Her family was a slave-owning household, and she grew up in an affluent and refined environment. When Mary was six years old, her mother died in childbirth. Two years later, her father married Elizabeth "Betsy" Humphreys, with whom he had nine more children. Mary had a difficult relationship with her stepmother. Through her father's two marriages, Mary had a total of 15 siblings and half-siblings. From 1832, Mary and her family resided in what is now known as the Mary Todd Lincoln House, an elegant 14-room residence located at 578 West Main Street in Lexington.

1.2. Education

At a young age, Mary was sent to Madame Mentelle's finishing school, where the curriculum focused on French and literature. She learned to speak French fluently and also studied dance, drama, music, and social graces. By the age of 20, she was considered witty and gregarious, possessing a strong understanding of politics. Like her family, she was a member of the Whig Party.

1.3. Family background

Mary's paternal great-grandfather, David Levi Todd, was born in County Longford, Ireland, and immigrated through Pennsylvania to Kentucky. Another great-grandfather, Andrew Porter, was the son of an Irish immigrant to New Hampshire and later Pennsylvania. Her great-great maternal grandfather, Samuel McDowell, was born in Scotland and emigrated to Pennsylvania. Other Todd ancestors came from England. The Todd family's wealth and social standing were significant, and their involvement with slavery was a notable aspect of Mary's upbringing, although Mary herself never owned slaves and later came to oppose slavery as an adult.

2. Marriage and family

Mary Todd Lincoln's personal life was deeply intertwined with her marriage to Abraham Lincoln and profoundly shaped by the tragic losses of their children.

2.1. Meeting and courtship

In October 1839, Mary began living with her married sister, Elizabeth Porter Edwards, in Springfield, Illinois. Elizabeth was married to Ninian W. Edwards, the son of a former governor, who served as Mary's guardian. Mary was popular among the gentry of Springfield. Although she was courted by the rising young lawyer and Democratic Party politician Stephen A. Douglas and others, she ultimately chose Abraham Lincoln, a fellow Whig.

2.2. Marriage

Mary Todd married Abraham Lincoln on November 4, 1842, at her sister Elizabeth's home in Springfield. She was 23 years old, and Lincoln was 33. Their marriage was a love match, despite their contrasting personalities; Mary was known for being social and extravagant, while Lincoln was more reserved.

2.3. Children

Mary and Abraham Lincoln had four sons, all born in Springfield, Illinois:

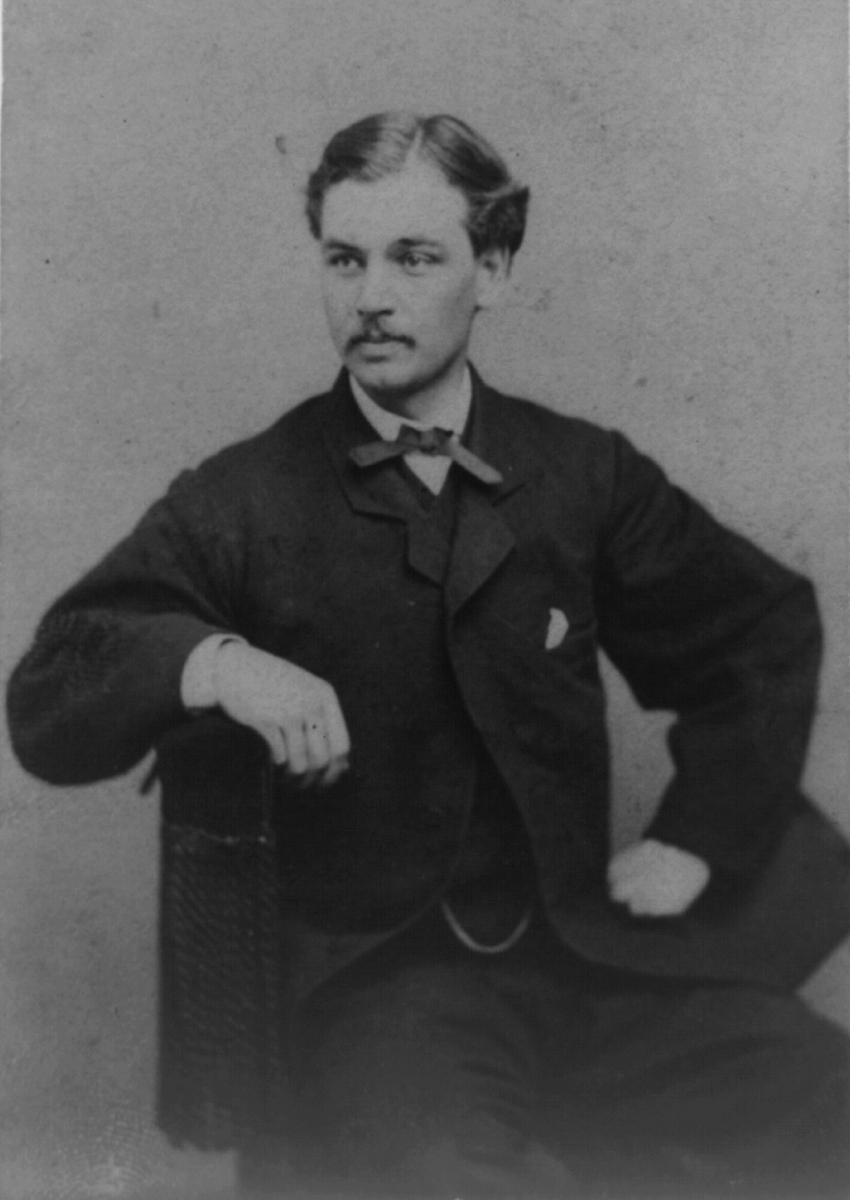

- Robert Todd Lincoln (1843-1926), who became a lawyer, diplomat (including U.S. Secretary of War), and businessman.

- Edward Baker Lincoln, known as "Eddie" (1846-1850), who died of tuberculosis.

- William Wallace Lincoln, known as "Willie" (1850-1862), who died of typhoid fever while Lincoln was President.

- Thomas Lincoln, known as "Tad" (1853-1871), who died at age 18, possibly from pleurisy, pneumonia, congestive heart failure, or tuberculosis.

Only Robert and Tad survived their father, and only Robert outlived his mother. The deaths of three of her sons at young ages caused Mary immense and prolonged grief, profoundly impacting her mental and emotional state.

3. Lincoln's career and home life

While Lincoln pursued his increasingly successful career as a lawyer in Springfield, Mary supervised their growing household. Their home, where they resided from 1844 until 1861, still stands in Springfield and has been designated the Lincoln Home National Historic Site. During Lincoln's years as an Illinois circuit lawyer, Mary was often left alone for months at a time to raise their children and manage the household. Lincoln's legal work was successful, with his annual income reaching 1.20 K USD, equivalent to a governor's salary at the time. However, this required him to travel extensively on the circuit, sometimes riding 31 mile (50 km) a day. Mary staunchly supported her husband socially and politically, especially when Lincoln was elected president in 1860. Despite being raised in a wealthy family, Mary's cooking was simple but satisfied Lincoln's tastes, which included imported oysters.

4. First Lady of the United States

Mary Lincoln's tenure as First Lady was marked by her efforts to fulfill her social responsibilities amidst the immense pressures and personal difficulties of the American Civil War.

4.1. Role and activities

During her years in the White House, Mary Lincoln actively worked to maintain national morale during the Civil War. She served as the White House social coordinator, hosting numerous social functions and attempting to navigate the complex social landscape of wartime Washington, D.C., which was dominated by eastern culture. Despite being considered a "westerner" due to her upbringing in Lexington, Kentucky, she worked hard to fulfill her role as First Lady. She frequently visited hospitals around Washington to bring flowers and fruit to wounded soldiers and took the time to write letters for them to send to their loved ones. From time to time, she also accompanied Lincoln on military visits to the field.

4.2. White House redecoration and spending

Mary undertook extensive redecoration of the White House, including all public and private rooms, and purchased new china. These efforts led to significant overspending, which became a source of public and private controversy. President Lincoln was reportedly very angry over the costs, even though Congress eventually passed two additional appropriations to cover these expenses. Mary was also a frequent purchaser of fine jewelry, often buying on credit from local jewelers. Upon President Lincoln's death, she had a substantial debt with the jeweler, which was subsequently waived, and much of the jewelry was returned. Her lavish spending habits were a recurring point of criticism throughout her time as First Lady.

4.3. Challenges during the Civil War

Mary faced numerous challenges during the Civil War, compounded by the nation's political divisions. Her family was from a border state where slavery was permitted, and several of her half-brothers served in the Confederate Army, with some killed in action, and one serving as a Confederate surgeon. Despite these family ties, Mary staunchly supported her husband's quest to save the Union and remained strictly loyal to his policies. However, critics often described her manners as coarse and pretentious, and she struggled with the social rivalries, demands from spoils-seeking solicitors, and critical newspaper coverage in the highly charged atmosphere of Civil War Washington.

5. Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln endured the harrowing experience of witnessing her husband's assassination, which plunged her into an incapacitating state of grief.

5.1. Witnessing the assassination

As the American Civil War concluded, Mary Lincoln anticipated continuing her role as First Lady of a nation at peace. On the morning of April 14, 1865, President Lincoln was in a pleasant mood, with Robert E. Lee having surrendered days earlier, and awaiting news of Joseph E. Johnston's surrender in North Carolina. Newspapers had announced that the President and his wife would attend the theater that evening. Although Mary developed a headache and initially considered staying home, Lincoln insisted they go, citing the public announcement.

Mrs. Lincoln sat beside her husband, watching the comic play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre, accompanied by their guests Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris. During the third act, the Lincolns drew closer, holding hands and enjoying the play. In their final conversation, Mary whispered to her husband, "What will Miss Harris think of my hanging on to you so?" The President smiled and replied, "She won't think anything about it." Approximately five minutes later, at about 10:15 p.m., John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln. Mary was holding Abraham's hand when Booth's bullet struck the back of his head.

5.2. Immediate aftermath and grief

Following the shooting, Mrs. Lincoln accompanied her mortally wounded husband across the street to the Petersen House, where he was taken to a back bedroom. Lincoln's Cabinet was summoned, with the exception of William H. Seward, who had been seriously attacked by Lewis Powell shortly before Booth's assassination attempt. Their eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, remained with his father throughout the night until the following morning, Saturday, April 15, 1865. At one point, Edwin M. Stanton, Lincoln's Secretary of War, ordered Mary from the room due to her extreme and unhinged grief.

President Lincoln remained in a coma for approximately nine hours, dying at 7:22 a.m. at the age of 56. Shortly before 7 a.m., Mary was permitted to return to Lincoln's side, where she reportedly "seated herself by the President, kissing him and calling him every endearing name." As he died, his breathing grew quieter, and his face became more calm. According to some accounts, at his last breath, he smiled broadly before expiring. Historians have emphasized Lincoln's peaceful appearance in death, with Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Maunsell Bradhurst Field noting, "I had never seen upon the President's face an expression more genial and pleasing." His secretary, John Hay, stated, "A look of unspeakable peace came upon his worn features." The profound grief that afflicted Mary after Lincoln's death was incapacitating, adding to her already heavy burden of sorrow from the loss of her children.

6. Health issues and mental state

Mary Todd Lincoln's life was marked by ongoing struggles with both physical and mental health, which were often exacerbated by the profound personal tragedies she endured. Historical and psychological interpretations of her condition have evolved over time, reflecting changing medical understanding and societal views.

6.1. Physical health

Throughout her adult life, Mary suffered from severe headaches, often described as migraines. These headaches seemed to become more frequent after she sustained a head injury in a carriage accident during her White House years in 1863. She also experienced other recurring physical ailments that significantly impacted her overall well-being. Some theories suggest that her physical symptoms, alongside her mental health issues, could be manifestations of pernicious anemia.

6.2. Mental health and controversies

Mary Lincoln exhibited a history of mood swings, a fierce temper, public outbursts during Lincoln's presidency, and excessive spending. These behaviors have led some historians and psychologists to theorize that she suffered from bipolar disorder. Other interpretations suggest she experienced protracted depression. The societal reactions to her behavior were often critical, labeling her as "crazy" or "unhinged," reflecting the limited understanding of mental illness during her era. In 1872, Mary sought out spirit photographer William H. Mumler, who produced a photograph appearing to show the faint "ghost" of her husband behind her. Mary reportedly visited Mumler's studio under the pseudonym "Mrs. Lindall" and identified the spectral figure as Lincoln, though Mumler's photos are now widely recognized as hoaxes created through double exposure.

6.3. Impact of grief

The cumulative losses of her children and husband profoundly contributed to Mary's severe and prolonged psychological distress. Her grief over Willie's death in 1862 was so devastating that she remained bedridden for three weeks, unable to attend his funeral or care for her youngest son, Tad. Lincoln had to employ a nurse to look after her during this period. Tad's death in July 1871, following the deaths of Eddie and Willie, and her husband, brought on an overpowering grief and depression, further exacerbating her mental instability.

7. Later life and institutionalization

Mary Todd Lincoln's life following her husband's death was characterized by financial difficulties, periods of travel, and a controversial institutionalization.

7.1. Life after assassination and financial struggles

After her husband's death, Mary Lincoln returned to Chicago, Illinois, to live with her sons. Abraham Lincoln had left an estate of 80.00 K USD, which should have provided her with comfort. However, Mary had a lavish and unstable relationship with money. In 1868, she publicly advertised for aid in the New York World and attempted to sell her personal effects at auction, which shocked the public. While living in Europe, the Seligman family provided her with financial assistance, covering the cost of her voyage and sending her money. Despite receiving a government pension and having a significant amount of money in government bonds, she lived in constant fear of poverty. She was known to walk around the city with 56.00 K USD in government bonds sewn into her petticoats.

7.2. European travels

Mary and her youngest son, Tad, moved to Europe, settling in Frankfurt, Germany, for several years, where Tad attended school. After Tad's death, she spent the next four years traveling throughout Europe, taking up residence in Pau, France, seeking relief and a change of environment.

7.3. Pension and lobbying

Mary lobbied hard for a government pension, writing numerous letters to Congress and urging patrons like Simon Cameron and Joseph Seligman to petition on her behalf. She argued that she deserved a pension just as much as soldiers' widows, portraying her husband as a fallen commander. On July 14, 1870, the United States Congress granted her a life pension of 3.00 K USD a year. At the time, a pension for presidential widows was unusual, and Mary's strained relationships with many congressmen made it difficult to gain approval. After the assassination of President Garfield in 1881, which raised the issue of provisions for his family, Mary traveled to New York and successfully lobbied for an increased pension, along with an additional monetary gift, despite facing negative press regarding her spending habits and financial management.

7.4. Institutionalization and release

Mary's surviving son, Robert Todd Lincoln, a rising young lawyer in Chicago, became alarmed by his mother's increasingly erratic behavior. In March 1875, during a visit to Jacksonville, Florida, Mary became convinced that Robert was deathly ill, only to find him healthy upon her hurried return to Chicago. During this visit, she claimed someone tried to poison her on the train and that a "wandering Jew" had taken and returned her pocketbook. She also spent large sums on items she never used, such as draperies and elaborate dresses, despite wearing only black after her husband's assassination.

Due to her behavior, Robert initiated legal proceedings to have her institutionalized. On May 20, 1875, a jury committed her to a private asylum in Batavia, Illinois, known as Bellevue Place. After the court proceedings, she was so despondent that she attempted suicide by ordering enough laudanum to kill herself from several pharmacies, but an alert pharmacist thwarted her attempts by giving her a placebo.

Three months into her commitment at Bellevue Place, Mary devised an escape plan. She smuggled letters to her lawyer, James B. Bradwell, and his wife, Myra Bradwell, who was a friend and a feminist lawyer. She also wrote to the editor of the Chicago Times. The public embarrassment Robert had hoped to avoid began to loom, and his character and motives were questioned, especially as he controlled his mother's finances. Facing potentially damaging publicity, the director of Bellevue declared her well enough to leave and live with her sister Elizabeth in Springfield, as Mary desired. Mary Lincoln was released into her sister's custody, and in 1876, she was declared competent to manage her own affairs. However, the committal proceedings resulted in a profound estrangement between Mary and her son Robert, and they did not see each other again until shortly before her death.

7.5. Final years

During the early 1880s, Mary Lincoln was confined to the Springfield, Illinois, residence of her sister Elizabeth Edwards. Her final years were marked by declining health. She suffered from severe cataracts that significantly reduced her eyesight, a condition that may have contributed to her increasing susceptibility to falls. In 1879, she sustained spinal cord injuries in a fall from a stepladder.

8. Death

On July 15, 1882, exactly eleven years after her youngest son, Tad, died, Mary Todd Lincoln collapsed at her sister's home. She lapsed into a coma and died the following morning, July 16, 1882, of a stroke at the age of 63. Her funeral service was held at First Presbyterian Church in Springfield. She is buried with her husband and three younger sons in the Lincoln Tomb at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

9. Regard by historians and legacy

Mary Todd Lincoln's life and role have been subject to extensive analysis by historians, and her character has been frequently depicted in popular culture, reflecting diverse and evolving interpretations of her complex personality.

9.1. Historical assessment

Historians have often regarded Mary Todd Lincoln poorly as a First Lady, frequently characterizing her as meddling and disruptive. This negative perception is largely attributed to her perceived psychological conditions, which are thought to have complicated President Lincoln's life. Scholars acknowledge that she likely suffered from mental illness during her husband's presidency, and that the personal toll of losing two children, including one during his term, significantly impacted her well-being. The American author Dale Carnegie famously stated, "His (Abraham Lincoln's) assassination was not as tragic as his marriage."

Since 1982, the Siena College Research Institute has periodically conducted surveys asking historians to assess American first ladies based on criteria such as background, value to the country, intelligence, courage, accomplishments, integrity, leadership, being their own women, public image, and value to the president. In the first four surveys, Mary Lincoln consistently ranked in the lowest quartile. For example, in the 2008 Siena Research Institute survey, she was ranked the lowest in four of the ten criteria: value to the country, accomplishments, leadership, and public image.

However, in the fifth survey conducted in 2020, Mary Lincoln's standing had risen sufficiently to place her in the third quartile. This improvement in regard, from being ranked as the worst First Lady in the initial survey to the third quartile in 2020, is possibly due to an increase in scholarly writing and re-evaluation of her life. In terms of cumulative assessment, her rankings have shown a gradual improvement:

- 42nd-best of 42 in 1982

- 37th-best of 37 in 1993

- 36th-best of 38 in 2003

- 35th-best of 38 in 2008

- 31th-best of 39 in 2014

- 29th-best of 40 in 2020

Despite her individual low rankings in some areas, the 2014 survey ranked Mary Lincoln and her husband as the 7th-highest out of 39 first couples in terms of being a "power couple," indicating their significant combined influence.

9.2. Cultural depictions

Mary Todd Lincoln has been a recurring figure in literature, film, television, and theatre, reflecting diverse and evolving interpretations of her character.

In literature, Barbara Hambly's The Emancipator's Wife (2005) is a historical novel that provides context for her use of over-the-counter drugs containing alcohol and opium, which were common for women of her era. Janis Cooke Newman's historical novel Mary: Mrs. A. Lincoln (2007) depicts Mary telling her own story after her asylum incarceration, aiming to prove her sanity, and has been praised by biographer Jean H. Baker for its lifelike portrayal. The grief she experienced during her widowhood is a central theme in Andrew Holleran's 2006 novel, Grief. Another historical novel, Courting Mr. Lincoln (2019) by Louis Bayard, focuses on Lincoln's relationships with Mary Todd and Joshua Fry Speed in Springfield from 1839 to 1842. In 2005, Sufjan Stevens referenced Mary Todd Lincoln in the instrumental track "A Short Reprise for Mary Todd, Who Went Insane, but for Very Good Reasons" from his album Illinois.

On screen, Mary Lincoln has been portrayed by numerous actresses:

- Kay Hammond in Abraham Lincoln (1930)

- Marjorie Weaver in Young Mr. Lincoln (1939)

- Ruth Gordon in Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940)

- Julie Harris in The Last of Mrs. Lincoln (1976 television adaptation)

- Mary Tyler Moore in the 1988 television mini-series Lincoln

- Donna Murphy in the 1998 movie The Day Lincoln Was Shot

- Sally Field in Steven Spielberg's 2012 film Lincoln

- Penelope Ann Miller in Saving Lincoln (2012)

- Mary Elizabeth Winstead in Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter (2012)

- Lili Taylor in the 2024 Apple TV+ miniseries Manhunt

In theatre and opera, mezzo-soprano Elaine Bonazzi portrayed Mary in Thomas Pasatieri's Emmy Award-winning opera The Trial of Mary Lincoln in 1972. In 2024, the critically acclaimed play Oh, Mary! opened Off-Broadway, a dark comedy focusing on Mary Todd Lincoln's life during the end of the Civil War and leading up to Lincoln's assassination, weaving in queer elements and modern references. Writer Cole Escola drew inspiration from their own insecurities, later discovering Lincoln's own struggles with mental health aligned with the script's themes. Mrs. President, a play by John Ransom Phillips, centers on Mary Lincoln's interaction with the photographer Mathew Brady.

10. Family

Mary Todd Lincoln had extensive family connections, which provided both support and challenges throughout her life. Her sister, Elizabeth Todd, married Ninian Edwards Jr., the son of Illinois Governor Ninian Edwards. Their daughter, Julia Edwards, married Edward L. Baker Jr., who was the editor of the Illinois State Journal and the son of Edward L. Baker Sr. Julia and Edward's daughter, Mary Edwards Brown, who was Mary Todd Lincoln's grandniece, served as the custodian of the Lincoln Homestead, as did her own daughter.

Mary's half-sister, Emilie Todd, married Benjamin Hardin Helm, a CSA general and son of Kentucky Governor John L. Helm. Another half-sister, Elodie Todd, married CSA Brigadier General Nathaniel H. R. Dawson, who later became the third U.S. Commissioner of Education. One of Mary Todd's cousins was Dakota Territory Congressman and U.S. General John Blair Smith Todd.