1. Overview

Mary Louise Booth (April 19, 1831 - March 5, 1889) was a prominent American editor, translator, and writer, widely recognized for her pioneering role as the first editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar. Her career spanned significant periods of American history, including the American Civil War, during which she actively contributed to the Union cause through her extensive translation work. Booth's dedication to literature and journalism, coupled with her remarkable linguistic abilities, allowed her to break barriers in the male-dominated publishing world of the 19th century, establishing herself as an influential figure who shaped American domestic life and contributed significantly to the literary landscape.

2. Early Life and Background

Mary Louise Booth's early life was marked by intellectual precocity and a supportive family environment that fostered her exceptional talents.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Born in Millville, now Yaphank, New York, on April 19, 1831, Mary Louise Booth was described as a precocious child. She reportedly had no recollection of learning to read either French or English, suggesting an innate ability. Her mother noted that as soon as she could walk, Booth would follow her with a book in hand, eager to learn to read stories for herself. By the age of five, she had completed reading the entire Bible, for which she was rewarded with a multi-language version of the text. She also read Plutarch at a young age, a work that continued to bring her joy upon subsequent readings. At seven, she mastered the works of Racine in their original French, subsequently beginning the study of Latin with her father.

From that point onward, Booth became an indefatigable reader, preferring books to childhood play. Her father possessed a considerable library, and before her eleventh birthday, she had already familiarized herself with the works of Hume, Gibbon, Alison, and similar writers. Her parents took great care with her education, and her physical strength allowed her to pursue an uninterrupted course of study in various academies and through lessons with masters at home. She excelled particularly in languages and natural sciences, showing less interest in mathematics. Booth often learned more through self-study than at school. She taught herself French as a small child after encountering a French primer, becoming engrossed in comparing French words with English ones. She later acquired German in the same self-taught manner. Despite not hearing either language spoken, she became so proficient that in later years, she could translate almost any book from German or French, reading them aloud in English.

When Booth was about thirteen years old, her family relocated from Yaphank to Brooklyn, New York. There, her father organized the city's first public school, and Mary assisted him in teaching. Her father, William Chatfield Booth, a man deeply interested in academic matters, watched her growth with tender care and proudly cherished every word she wrote. He found it difficult to believe she could be entirely self-supporting, even after she achieved financial independence, and continued to offer her generous gifts.

2.2. Family Background

Mary Louise Booth was the daughter of William Chatfield Booth and Nancy Monswell. Her mother was of French descent, the granddaughter of a refugee from the French Revolution (1789-1799), and lived to be eighty years old. Her father, William Chatfield Booth, was a descendant of John Booth, an early settler who arrived in the United States around 1649. John Booth was a kinsman of the English politician Sir George Booth and was acquainted with Charles II's exiled companions. In 1652, John Booth purchased Shelter Island from the Native Americans for 300 ft of calico. The family remained in the vicinity for at least 200 years. For several years, William Chatfield Booth provided night-watchmen for large business houses in New York, personally supervising them from 9 PM to 7 AM. Besides Mary Louise, the family included another daughter and two sons, the younger of whom was Colonel Charles A. Booth, who served twenty years in the army.

3. Education and Early Career Preparation

Booth's determination to pursue a literary career led her to seek independence and embark on her professional journey.

3.1. Move to New York and Self-Reliance

As Booth matured, her resolve to make literature her profession grew immensely, and no discouragement could deter her. As the eldest of four children, she felt it would be unfair to her siblings to receive disproportionate aid from her father, as they might also require assistance in the future. Consequently, at the age of eighteen, she decided she needed to be in New York City for her work and could not depend entirely on her father. She made this decision independently, without disregarding her parents' wishes. She needed to earn the difference between what her father could provide and what she needed to live, while also finding time and opportunities for her chosen path.

A friend, who was a vest-maker, offered to teach Booth the trade, enabling her to execute her plan of moving to New York. She rented a small room in the city and returned home only on Sundays, as communication between Williamsburg (where her family resided) and New York was slow, taking no less than three hours for the journey. Two rooms were always kept ready for her at her parents' house, and these Sundays provided her with much-needed rest and enjoyment. However, her family showed little sympathy for her literary pursuits, so she rarely discussed them at home.

3.2. Early Literary Activities

From 1845 to 1846, Booth taught at her father's school in Williamsburg, New York, but she abandoned teaching due to health concerns and dedicated herself fully to literature. She contributed tales and sketches to various newspapers and magazines, though initially without monetary compensation. She began reporting and reviewing books for educational and literary journals, still unpaid in money, but content to be occasionally paid in books. She famously stated, "This is my college, and I must learn what I am doing before I demand pay." In 1856, she compiled a manual for marble workers, similar to one published in France, and though it was published, she again received only books as compensation. Despite sometimes lacking carfare and having to walk 4 mile, she steadily progressed, receiving more and more literary assignments as time went on. Her circle of friends widened to include those who began to appreciate her abilities.

In 1859, she agreed to write a history of New York, but even then, she could not fully support herself, despite having given up vest-making and writing twelve hours a day. When she was thirty years old, she accepted a position as an amanuensis for Dr. J. Marion Sims, a physician often called the "father of modern gynecology." This was the first work of its kind for which she received steady payment. This allowed her to live independently in New York without her father's assistance, albeit very plainly.

4. Literary Career and Translation Activities

Booth's literary career was marked by significant contributions as both a writer and a prolific translator, particularly during the American Civil War.

4.1. Early Writings and Translations

Booth's early translation works included The Marble-Worker's Manual (New York, 1856) and The Clock and Watch Maker's Manual, both translated from French. She also translated Joseph Méry's André Chénier and Edmond François Valentin About's The King of the Mountains for Emerson's Magazine, which also published her original articles. Her next translation was Victor Cousin's Secret History of the French Court: or, Life and Times of Madame de Chevreuse (1859).

That same year, the first edition of her most prized possession, History of the City of New York, was published. The idea for this work originated when a friend suggested that no complete history of New York City had been written and that a version suitable for schools might be beneficial. Booth, then a young woman, immediately immersed herself in the undertaking, undeterred by the low probability of success. After several years of preparation, her draft became the basis for a more substantial work at the request of a publisher. She recognized that the history of New York was far from trivial, as many of the most moving events in colonial and national history were connected to it.

During her research, Booth had full access to libraries and archives. Washington Irving sent her a letter of cordial encouragement, and prominent figures such as D. T. Valentine, Henry B. Dawson, William John Davis, and Edmund Bailey O'Callaghan provided her with documents and assistance. Historian Benson John Lossing commended her, stating, "My Dear Miss Booth, the citizens of New York owe you a debt of gratitude for this popular story of the life of the great metropolis, containing so many important facts in its history, and included in one volume accessible to all. I congratulate you on the completeness of the task and the admirable manner in which it has been performed."

Booth's history of New York City was published in one large volume and was so well-received that it brought her substantial financial compensation. The publisher was so pleased with its success that they proposed she travel abroad to write popular histories of major European capitals, including London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna. However, the impending American Civil War and other circumstances prevented her from traveling. A second edition of her History was published in 1867, and a third, revised edition appeared in 1880. A large paper edition was acquired by renowned book collectors, who expanded and illustrated it with thousands of supplementary prints, portraits, and autographs. One copy, enlarged to folio and extended to nine volumes with several thousand maps, letters, and other illustrations, became an unrivaled treasure trove owned in New York City. Booth herself owned another copy, enriched with over two thousand illustrations on inserted leaves.

She also assisted Orlando Williams Wight in translating a series of French classics and translated About's Germaine (Boston, 1860).

4.2. Civil War Era Contributions

Shortly after the publication of her History of the City of New York, the American Civil War erupted. Booth had always been a staunch anti-slavery partisan and sympathized with movements for what she considered progress. During this period, the nation was inflamed with passion to prevent the destruction of a noble government, and everyone sought true universal liberty, not merely a false, ostentatious freedom. Booth ardently supported the Union cause and longed to contribute. Although she felt unqualified to serve as a nurse in military hospitals due to her lack of experience, she believed she had to do something.

Upon receiving an advance copy of Count Agénor de Gasparin's French work, Un Grand Peuple Qui Se Releve (Uprising of a Great People), she immediately recognized an opportunity to assist. She took the book to Charles Scribner, proposing its publication. Scribner initially hesitated, stating that while he would gladly publish it if the translation were ready, the war might end before the book was out. He challenged her, saying he would publish it if it could be ready in a week. Booth's immediate reply was, "It can be done in a week." She returned home and worked twenty hours a day, receiving proof-sheets at night and returning them with fresh copy in the morning. She completed the translation hours before the deadline, and the book was published within a fortnight. The book created an immense sensation among Unionists, its message resonating from Maine to California. Newspapers of the day were filled with reviews and notices, both eulogistic and critical, depending on the political party. Senator Sumner wrote, "It is worth a whole phalanx in the cause of human freedom." President Lincoln paused from his immense duties to send her a letter of thanks and high commendation. Despite the profound impact of her work, Booth received little financial compensation for this translation.

The publication of this translation led to communication between Booth, Gasparin, and his wife, who invited her to visit them in Switzerland. She also began a correspondence with other European sympathizers of the Union, including Augustin Cochin, Édouard René de Laboulaye, Henri Martin, and Charles Forbes René de Montalembert. These gentlemen, united by their hatred of slavery, eagerly sent her numerous articles, letters, and pamphlets, vying to be the first to send documents for translation and consultation. Booth accurately informed these noble Frenchmen about the progress of events they inquired about and sent them publications that might be useful. During the war, she translated many French books designed to rouse patriotic feeling. At one point, she was summoned to Washington, D.C. to write for statesmen, receiving only her board at a hotel. During this time, she was able to arrange a clerk position for her father at the New York Custom House, relieving him from his arduous night work.

4.3. Major Translation Works

Booth's extensive translation projects from French and other languages ran to nearly forty volumes. In rapid succession during the Civil War era, she translated:

- Gasparin's America before Europe (New York, 1861)

- Cochin's Results of Emancipation and Results of Slavery (Boston, 1862)

- Laboulaye's Paris in America (New York, 1865)

For the Cochin translations, she received praise and encouragement from President Lincoln, Senator Sumner, and other statesmen. Senator Sumner notably stated that Cochin's work "was of more value than the Numidian cavalry to Hannibal." She also translated Countess de Gasparin's religious works: Vesper, Camille, and Human Sorrows, as well as Count Gasparin's Happiness. Documents forwarded to her by French friends of the Union were translated and published as pamphlets by the Union League Club or printed in New York journals.

Booth also translated Henri Martin's History of France. The two volumes covering The Age of Louis XIV were issued in 1864, and two others, the last of the original seventeen volumes, appeared in 1866 under the title The Decline of the French Monarchy. Although she translated two more volumes from the beginning of the series, the enterprise was eventually abandoned, and no further volumes were printed. Her translation of Martin's abridgment of his History of France was published in 1880.

Further demonstrating her versatility, she translated Laboulaye's Fairy Book, Jean Macé's Fairy Tales, and Blaise Pascal's Provincial Letters. She received hundreds of appreciative letters from statesmen, including Henry Winter Davis, Senator James Rood Doolittle, Galusha A. Grow, Dr. Francis Lieber, Dr. Bell (the president of the Sanitary Commission), Cassius M. Clay, and Attorney-General James Speed. She had considered adding to her extensive body of work an abridgment of George Sand's voluminous Histoire de ma vie at the request of James T. Fields, but circumstances prevented its completion.

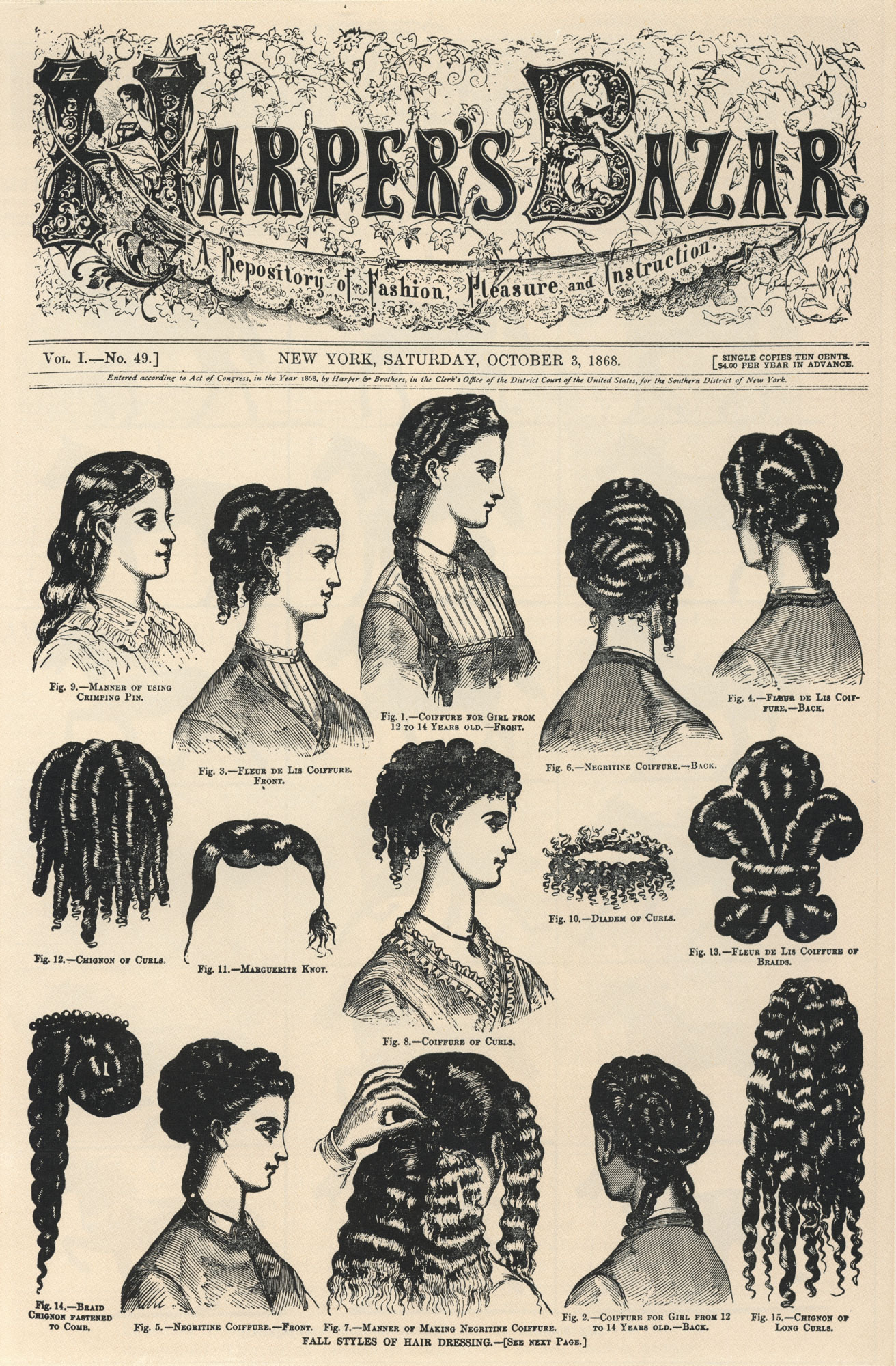

5. Harper's Bazaar

Booth's most significant professional role was as the founding editor of Harper's Bazaar, a position she held for over two decades.

5.1. Founding and Editorial Leadership

In 1867, Booth undertook another major enterprise, assuming the management of Harper's Bazaar, a weekly journal dedicated to the pleasure and improvement of the home. She had long maintained good relations with the Harper brothers-James, John, Joseph, and Fletcher-who founded the publishing house that bore their name and successfully conducted its business. When they decided to launch the first women's fashion magazine, they immediately asked her to take charge of the editorship.

Booth was initially diffident about her abilities but ultimately accepted the responsibility. She served as its first editor-in-chief from its inception in 1867 until her death in 1889.

5.2. Influence and Success

Under Booth's editorial management, Harper's Bazaar achieved remarkable and rapid journalistic success, numbering its subscribers in the hundreds of thousands. Other newspaper companies initially underestimated her abilities and anticipated losses, but the magazine proved them wrong. It maintained its character as a home paper while steadily increasing its influence and circulation. The purity, self-respect, high standards, and literary excellence of Harper's Bazaar were unparalleled among periodicals. Poets, story writers, and novelists of every class in America and England contributed to its pages.

The magazine consistently featured good and entertaining content, prioritizing the happiness and virtue of women and families, and fostering a wholesome atmosphere wherever it was read. Booth herself was the inspiration for the entire editorial team, even with assistants in every department. The influence of such a publication within American homes was immense; through its columns, Booth's hand was felt in countless families for nearly sixteen years, helping to shape the domestic life of a generation into one of peace and righteousness. It is said that she received a larger salary than any other woman in the United States at that time.

6. Personal Life

Mary Louise Booth's personal life was characterized by a close companionship and a vibrant social circle.

6.1. Residence and Social Circle

Booth lived in New York City, in a house she owned near Central Park. Her home was well-suited for entertaining, and there were always guests. Every Saturday night, her salon hosted an assemblage of prominent authors, singers, players, musicians, statesmen, travelers, publishers, and journalists. Booth was described as sensitive, sympathetic, and delicate, and she was blessed with unwavering friends, finding contentment in their happiness without seeking to serve or be subservient to others.

6.2. Companion

Booth shared her home with her long-time companion, Mrs. Anne W. Wright. Their close friendship began in childhood and continued throughout their lives.

7. Death

Mary Louise Booth died in New York City after a short illness on March 5, 1889.

8. Achievements and Legacy

Mary Louise Booth left an indelible mark on American literature and journalism, earning recognition from influential figures and paving the way for future generations of women.

8.1. Recognition from Notable Figures

Throughout her career, Booth received widespread praise and commendations from influential contemporaries. President Abraham Lincoln and Senator Charles Sumner both sent her letters of gratitude for her impactful translation of Gasparin's Uprising of a Great People during the Civil War. Historian Benson John Lossing lauded her History of the City of New York, recognizing the debt of gratitude owed to her by New Yorkers for her accessible and fact-rich account of the metropolis. Publishers were so impressed with her work that they proposed she write histories of European capitals. She also received hundreds of appreciative letters from statesmen such as Henry Winter Davis, Senator James Rood Doolittle, Galusha A. Grow, Dr. Francis Lieber, Dr. Bell (the president of the Sanitary Commission), Cassius M. Clay, and Attorney-General James Speed, acknowledging the value of her translations in supporting the Union cause.

8.2. Pioneering Role as a Woman

Mary Louise Booth's achievements are particularly notable given the male-dominated professional landscape of the 19th century. She excelled in fields traditionally reserved for men, becoming the first editor-in-chief of a major publication like Harper's Bazaar and earning an unprecedented salary for a woman of her time. Her dedication to literature, her remarkable linguistic skills, and her unwavering perseverance allowed her to overcome societal barriers. By demonstrating exceptional talent and leadership in journalism and publishing, Booth served as a significant role model, contributing to the advancement of professional opportunities for women and inspiring future generations to pursue their ambitions in intellectual and public spheres.