1. Life

Liu He's personal journey began with his lineage rooted in the imperial family, leading to his early life as a king before his unexpected accession to the throne.

1.1. Ancestry and Childhood

Liu He was the grandson of Emperor Wu of Han. His father, Liu Bo (劉髆Liú BóChinese), known as King Ai of Changyi (昌邑哀王Chāngyì ĀiwángChinese), died in 88 BC. Liu He inherited his father's kingdom in 86 BC, implying he was a toddler at the time. Liu Bo was one of Emperor Wu's sons, and after Liu Ju, Emperor Wu's crown prince, committed suicide in 91 BC, Liu Bo was considered a candidate for the crown prince title, though it ultimately went to the young Liu Fuling.

1.2. As King of Changyi

During his teenage years as King of Changyi, Liu He's behavior was often criticized. Wang Ji (王吉Wáng JíChinese), the mayor of the kingdom's capital, offered honest criticism of Liu He's inappropriate conduct, urging him to be more studious and humble. While Liu He reportedly appreciated Wang's advice and rewarded him, he did not change his ways. Similarly, Gong Sui (龔遂Gōng SuíChinese), the commander of his guards, pleaded with him to alter his association with people of ill repute who engaged in vulgarity and wasteful spending. Liu He agreed but soon dismissed the guards Gong had recommended, bringing back his previous companions. Historical accounts of Liu He's life as King of Changyi are largely based on materials written after his deposition, and therefore may contain biases or fabrications.

2. Accession to the Throne

The circumstances surrounding Liu He's ascension were marked by political maneuvering and his own controversial conduct. When his uncle, Emperor Zhao of Han, died in 74 BC without a son, the regent Huo Guang faced a succession crisis. Huo Guang rejected Liu Xu (劉胥Liú XūChinese), the Prince of Guangling and Emperor Wu's only surviving son, from the succession, as Emperor Wu himself had not favored Prince Xu. Huo Guang then turned to Liu He, as he was Emperor Wu's grandson.

Liu He was reportedly very pleased with this decision and immediately departed from his capital, Shanyang (in modern Jining, Shandong), heading for the imperial capital Chang'an. His pace was so frenetic that his guards' horses died from exhaustion. Wang Ji advised him against such haste, reasoning it was inappropriate during a period of mourning, but Liu He dismissed the suggestion. Along the way, he ordered local officials to provide him with a special kind of chicken known for its prolonged crowing, and women. This behavior was highly inappropriate, as he was required to abstain from sexual relations during mourning. When Gong Sui confronted him about these actions, Liu He blamed his director of slaves, who was subsequently executed. Upon arriving at the capital, Liu He first stayed at the Changyi mission before attending a formal mourning session for Emperor Zhao and accepting the throne.

3. Brief Reign and Deposition

Liu He's reign was exceptionally short, marked by alleged misconduct that quickly led to his downfall.

3.1. Emperor's Conduct

Immediately upon becoming emperor, Liu He began granting rapid promotions to his subordinates from Changyi. He also failed to observe the proper period of mourning for Emperor Zhao, instead engaging in feasts day and night and embarking on tours. Gong Sui, his former guard commander, became increasingly concerned but was unable to persuade Liu He to change his ways. His behavior surprised and disappointed Huo Guang, who began to consider deposing the new emperor at the suggestion of the agricultural minister Tian Yannian (田延年Tián YánniánChinese).

3.2. Impeachment and Removal

Just 27 days into Liu He's reign, Huo Guang, along with other high-ranking officials, moved to depose him. They convened a meeting of officials, announcing their plan and coercing others to comply under threat of death. The group then proceeded to Empress Dowager Shangguan's palace to report Liu He's offenses and their plan. She agreed and ordered Liu He's Changyi subordinates to be immediately barred from the palace. Approximately 200 of these subordinates were then arrested by Zhang Anshi (張安世Zhāng ĀnshìChinese).

Empress Dowager Shangguan then summoned Liu He, who was unaware of the impending events. He realized something was amiss only upon seeing the Empress Dowager seated on her throne in formal jeweled attire, with officials lined up beside her. Huo Guang and the top officials presented their articles of impeachment against Prince He, which were read aloud to the Empress Dowager. Empress Dowager Shangguan verbally rebuked Liu He. The articles of impeachment cited a total of 1127 examples of misconduct during his 27-day reign, with the main offenses including:

- Refusal to abstain from meat and sexual activity during the mourning period.

- Failure to keep the imperial safe secure.

- Improperly promoting and rewarding his Changyi subordinates during the mourning period.

- Engaging in feasts and games during the mourning period.

- Offering sacrifices to his father during the mourning period for his uncle.

Empress Dowager Shangguan approved the articles of impeachment and ordered Liu He's deposition. He was then transported under heavy guard back to the Changyi mission. Both Liu He and Huo Guang reportedly offered personal apologies to each other.

4. Post-Reign Life and Demotion

After his deposition, Liu He's life took a drastically different turn, marked by demotion and a quiet existence until his death. As part of the impeachment articles, officials had requested that Empress Dowager Shangguan exile Liu He to a remote location. However, she instead returned him to Changyi without any titles, though he was granted a small fief of 2,000 families who would pay tribute to him. His four sisters were also awarded smaller fiefs of 1,000 families each.

Liu He's Changyi subordinates were accused of failing to control his behavior and were almost all executed. Wang Ji and Gong Sui were spared due to their prior attempts to advise him, but they were sentenced to hard labor. The only other official spared was Liu He's teacher, Wang Shi (王式Wáng ShìChinese), who successfully argued that he had tried to guide Liu He through the teachings of poems. Some historians suggest that the severe punishment of the Changyi officials stemmed from Huo Guang's suspicion that they were plotting with Liu He to assassinate him, though conclusive evidence for such a plot or its direct link to the harsh treatment remains debated.

Huo Guang later selected Liu Bingyi (劉病已Liú BǐngyǐChinese), the commoner grandson of the former Crown Prince Liu Ju (and thus an uncle of Liu He), as the new emperor. Liu Bingyi ascended the throne 27 days later as Emperor Xuan of Han. For years, despite Liu He being powerless and without titles, Emperor Xuan remained suspicious of him. However, a report in 64 BC by Zhang Chang (張敞Zhāng ChǎngChinese), the governor of Shanyang Commandery, alleviated these concerns by downplaying Liu He's intelligence.

In 63 BC, Emperor Xuan made Liu He the Marquis of Haihun, a county located in modern Jiangxi Province. This relocation is believed to be a measure to distance him from his former principality, reflecting Emperor Xuan's lingering concerns despite Zhang Chang's report. Liu He died on September 8, 59 BC, at the age of 33, as a marquess, survived by 16 wives and 22 children. Unprocessed melon seeds found in his stomach during archaeological excavation suggest he died in the summer. His eldest son, Liu Chongguo (劉充國Liú ChōngguóChinese), was initially designated to inherit the title but died. His second son, Liu Fengqin (劉奉親Liú FèngqīnChinese), also died. The succession of his title was initially not allowed, with the governor of Yuzhang proposing the abolition of the fief, which was accepted by the court. However, during the reign of Emperor Yuan of Han, Liu He's son Liu Daizong (劉代宗Liú DàizōngChinese) was eventually permitted to inherit the title of Marquis of Haihun. The Marquis of Haihun title continued to exist until the Later Han dynasty.

5. The Tomb of the Marquis of Haihun

The tomb of the Marquis of Haihun represents one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the Han dynasty, providing an unprecedented wealth of artifacts and textual materials.

5.1. Discovery and Excavation

The tomb of the Marquis of Haihun was discovered in 2011 in the northern part of Xinjian District in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, following reports of tomb raiding. The excavation process began shortly thereafter and confirmed the site as Liu He's burial place in March 2016. The tomb is part of a larger cemetery complex that contains a total of nine tombs.

5.2. Significance and Findings

The archaeological significance of the Marquis of Haihun's tomb is immense, yielding approximately 20,000 artifacts. Among these findings are over 300 gold objects, including gold coins, and around 2 million copper coins.

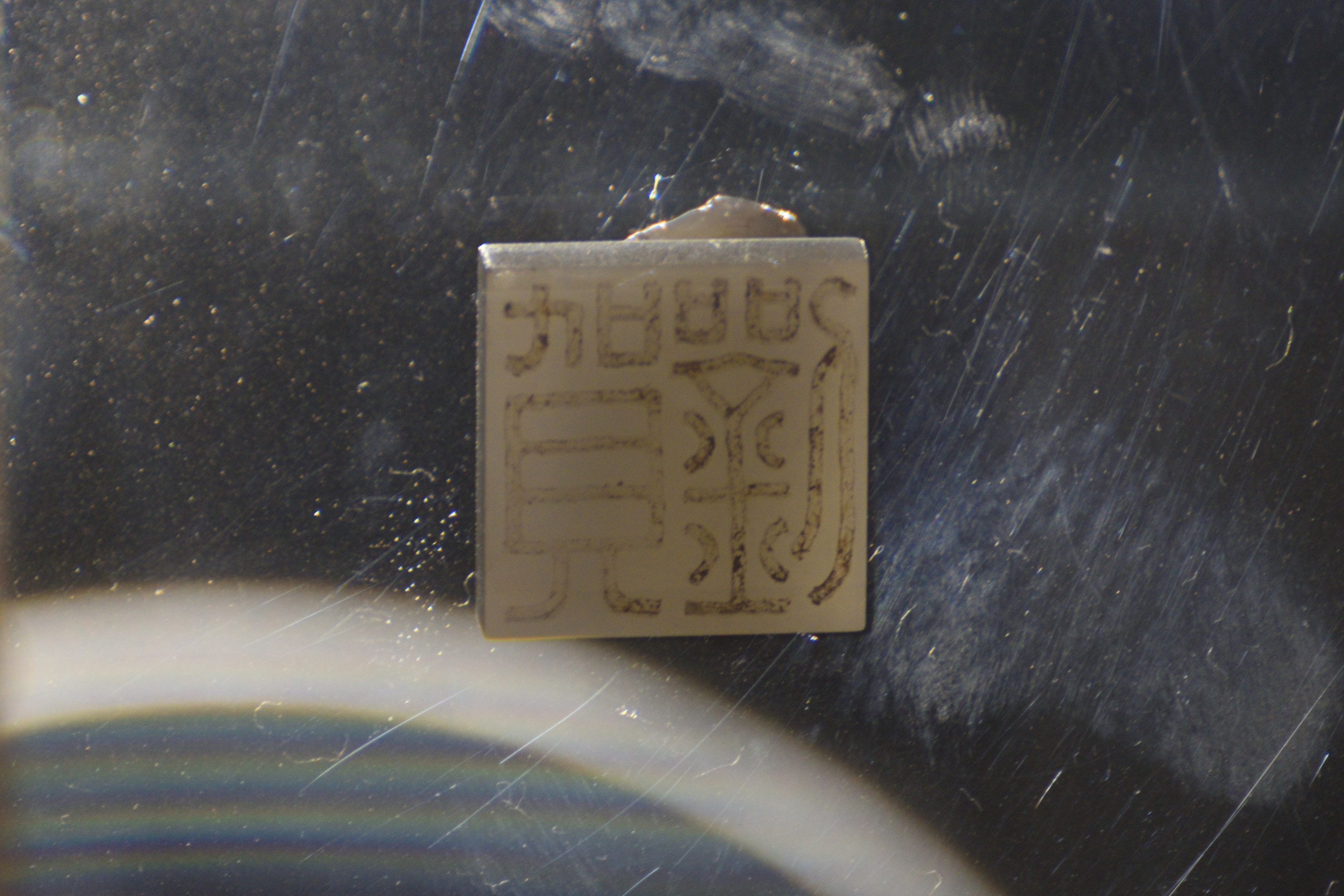

Notable discoveries include a mirror depicting the earliest known image of Confucius and his disciples, with their biographies inscribed around the depictions. This artifact, initially identified as a "dressing mirror," has been contested by scholar Jue Guo, who suggests it was a talisman. Another significant find is the long-lost Qi version of the Analects, which provides new insights into classical texts.

Over 5200 bamboo slips were unearthed from the tomb, containing remnants of an edict by Emperor Xuan of Han regarding the disestablishment of the fief of Haihun after the deaths of the Marquis and his sons. These slips have revealed information not recorded in traditional history books like the Book of Han, including the exact date of Liu He's death: September 8, 59 BC. The slips also mention that the fief of Haihun suffered numerous natural disasters, such as floods and drought. A report by the governor of Yuzhang concerning the fief's disestablishment, mentioned in the slips, corresponds with accounts in the Book of Han. Calculations from the slips indicate that the period between the deaths of the Marquis and his sons and the disestablishment of the fief was less than 40 days.

The process of disestablishing the Haihun fief was notably different from other fiefdoms. For instance, in September 112 BC, Emperor Wu of Han disestablished over 100 marquisates without court discussion. In contrast, the Haihun fief's disestablishment involved lengthy discussions with court officials, and the final edict was signed by over 100 officials, including the Chancellor Bing Ji (丙吉Bǐng JíChinese) and the Attorney General Xiao Wangzhi (蕭望之Xiāo WàngzhīChinese).

Preliminary studies of the tomb's textual content indicate manuscripts with partial overlap with the Book of Odes, the Analects, the Classic of Filial Piety, and the Spring and Autumn Annals. Other texts recovered include:

- The Bao fu (保傅Bǎo fùChinese), whose content was previously known from chapters in the Liji (禮記LǐjìChinese) and Da dai liji (大戴禮記Dà Dài LǐjìChinese).

- Approximately ten strips on morality, tentatively titled Li yi jian (禮儀簡Lǐyí JiǎnChinese, "Writings on rituals and morality").

- A text titled Dao wang fu (悼亡賦Dào wáng fùChinese), which appears related to expressions of mourning, though its content is difficult to interpret.

- A text covering the game Liubo (六博LiùbóChinese), a topic also discussed in other manuscripts from the Warring States period.

- A series of strips on divinations, with one group gathered under the title Yi zhan (易占Yì ZhānChinese), for their content on divination, including names and hexagrams.

Artifacts introduced in the journal Cultural Relics include:

- A dozen shields (35 in (90 cm) by 20 in (50 cm)), found on both sides of the main tomb's southern end, alongside long wooden poles. The shattered shields were recomposed by scholars. Two depict a dragon, and one portrays two humans seemingly fighting two animals, with a short inscription detailing the shield's material, cost, and production year. This practice of recording an object's value on the object itself is attested in Han culture.

- Two screens. One screen features a bronze mirror (approximately 38 in (96 cm) tall by 27 in (68 cm) across) framed by representations of King Father of the East (東王公DōngwánggōngChinese), Queen Mother of the West (西王母XīwángmǔChinese), and the "Four spirits" (四神SìshénChinese). Two badly preserved wooden pieces decorated with cranes were also found, possibly folding panels that originally covered the mirror. The verso side depicts Confucius and his disciples, with their biographies written around the depictions.

- A second screen, heavily fragmented due to its proximity to where tomb robbers initially entered. Two human figures are identifiable, with a brief inscription.

- A drum support, featuring an animal figure as its stand.

- A bronze distiller was also unearthed, suggesting the possibility that distilled alcohol was produced as early as the Western Han period.

6. Historical Evaluation and Legacy

Liu He's historical evaluation is complex, largely shaped by the accounts written after his deposition, which may be biased. The official narrative portrays him as an incompetent and immoral emperor whose brief reign was a period of chaos. The 1127 documented instances of misconduct serve to justify his swift removal from power.

However, some modern historians, such as the Japanese scholar Nishijima Sadao (西嶋定生Nishijima SadaoJapanese), have proposed alternative interpretations. Nishijima suggested that the unusual circumstances surrounding Liu He's deposition, including the harsh punishment of his loyal Changyi subordinates and their lamentations about "not doing what they should have done," might indicate a deeper political struggle. He theorized that Liu He and his faction may have been planning a coup d'état to seize actual power from the regent Huo Guang, but their plot was discovered, leading to a counter-coup by Huo Guang and his allies. In this view, officials like Wang Ji, Gong Sui, and Wang Shi, who were spared from execution, might have been informants. This perspective suggests that the historical accounts of Liu He's "misconduct" could have been exaggerated or fabricated to legitimize Huo Guang's actions and consolidate his power.

Regardless of the true extent of his alleged misdeeds, Liu He's brief reign and subsequent demotion highlight the immense power wielded by regents like Huo Guang during periods of imperial minority or weakness in the Han dynasty. His legacy is now increasingly influenced by the rich archaeological findings from his tomb, which offer a more direct and nuanced glimpse into the material culture and intellectual life of the Western Han elite, potentially allowing for a re-evaluation of his historical role beyond the politically charged narratives.

7. Family

Liu He's immediate family played a role in the continuation of his title after his death.

7.1. Sons

Liu He was survived by 16 wives and 22 children. His known sons include:

- Liu Chongguo (劉充國Liú ChōngguóChinese)

- Liu Fengqin (劉奉親Liú FèngqīnChinese)

- Liu Daizong (劉代宗Liú DàizōngChinese), who eventually inherited the title of Marquis of Haihun during the reign of Emperor Yuan of Han.