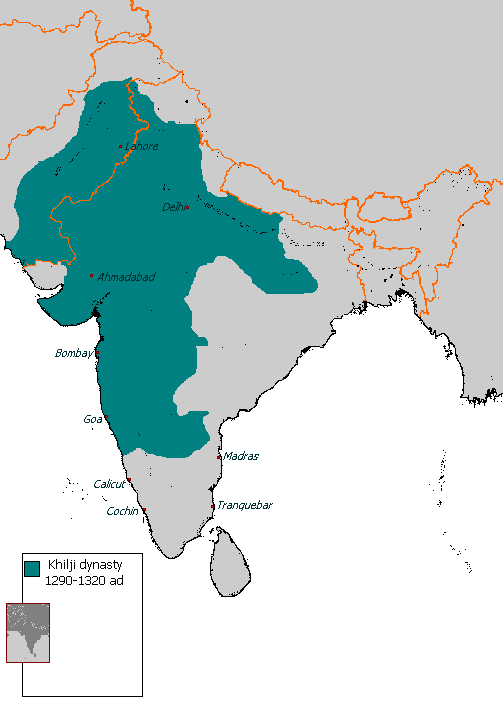

1. Early Life and Background

Malik Kafur's origins and early life reveal his humble beginnings before his meteoric rise within the Delhi Sultanate.

1.1. Origins and Captivity

Kafur was of Hindu descent, specifically described as a Mahratta by the 14th-century chronicler Isami. In his youth, he was the slave of a wealthy Khwaja (merchant) in the port city of Khambhat in Gujarat. He was an eunuch slave noted for his great physical beauty. He gained the epithet hazar-dinarithousand dinarPersian (meaning "of a thousand dinars") because he was said to have been purchased by his original master for 1,000 dinars. However, it is considered unlikely that the actual price was 1,000 dinars; the description appears to be a metaphorical compliment to his exceptional qualities. Ibn Battuta referred to Kafur as al-Alfithe thousandthArabic, the Arabic equivalent of hazar-dinari, though Ibn Battuta might have erred in stating that the Sultan Alauddin Khalji himself paid this sum.

Kafur was captured from Khambhat by Alauddin's general Nusrat Khan during the 1299 invasion of Gujarat. After his capture, Nusrat Khan presented him to Sultan Alauddin in Delhi.

1.2. Conversion and Early Service

Following his capture, Malik Kafur converted to Islam. Little is documented about his initial service under Alauddin, but he rapidly ascended in the ranks. According to Isami, Alauddin favored Kafur because his "counsel had always proved appropriate and fit for the occasion," highlighting Kafur's wisdom and strategic insight. By 1306, Kafur held the rank of barbeg, a position that combined the duties of a chamberlain with those of a military commander. His proven ability as a wise counsellor and effective military leader allowed him to progress quickly. By 1309-1310, he was granted the iqta' (administrative grant) of Rapri.

2. Military Career

Malik Kafur distinguished himself as one of Alauddin Khalji's most successful military commanders, leading crucial campaigns that significantly expanded the Delhi Sultanate's power and influence, particularly in southern India.

2.1. Repelling the Mongol Invasion

In 1306, Alauddin Khalji dispatched an army under Kafur's command to the Punjab to counter a major Mongol invasion launched by the Chagatai Khanate. The Mongol forces, led by Kopek, Iqbalmand, and Tai-Bu, had advanced to the Ravi River, plundering territories along their path. Kafur, with the crucial support of other commanders including Malik Tughluq, decisively routed the Mongol army. His success in this campaign solidified his reputation as a capable military leader. At this time, he was known as Na'ib-i Barbakassistant master of ceremoniesPersian, a title that some historians believe is the origin of his later, more prominent name Malik Na'ib. Although some accounts, such as the 16th-century chronicler `Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni, mistakenly credit Kafur with leading the 1305 Battle of Amroha, this claim is based on an erroneous identification with another officer, Malik Nayak.

2.2. Deccan and South India Campaigns

Following his triumph against the Mongols, Kafur was appointed commander of a series of ambitious military expeditions into the Deccan Plateau and the southernmost regions of India. These campaigns were instrumental in laying the foundations of Muslim power in the south and were primarily aimed at acquiring wealth rather than permanent territorial control, though they brought many tributary states under Delhi's influence.

2.2.1. Conquest of Devagiri

In 1307 or 1308, Alauddin Khalji ordered an invasion of the Yadava kingdom of Devagiri, whose king, Ramachandra, had ceased paying tribute to Delhi for several years. Originally, Alauddin considered another slave, Malik Shahin, for the leadership, but he fled. Alauddin then appointed Kafur as commander. To elevate Kafur's authority, Alauddin sent the royal canopy and pavilion with him and instructed all officers to daily pay their respects to Kafur and follow his orders. Kafur easily subjugated the Yadavas, securing rich spoils and bringing King Ramachandra to Delhi, where the Yadava king acknowledged Alauddin's suzerainty. Devagiri subsequently became a strategic base for the Sultanate's further expansion into southern India.

2.2.2. Conquest of Warangal

In 1309, Alauddin sent Kafur on an expedition to the Kakatiya kingdom. Kafur's army reached the Kakatiya capital, Warangal, in January 1310 and breached its outer fort after a month-long siege. The Kakatiya ruler, Prataparudra, surrendered and agreed to pay tribute. Kafur returned to Delhi in June 1310 with an immense amount of wealth, which reportedly included the legendary Koh-i-Noor diamond. Alauddin was highly pleased with Kafur's success and rewarded him handsomely.

2.2.3. Campaigns against the Hoysalas and Pandyas

Inspired by reports of immense wealth in India's southernmost regions, Kafur secured Alauddin's permission to lead another expedition. The campaign commenced on October 19, 1310. On February 25, 1311, Kafur, with 10,000 soldiers, besieged Dwarasamudra, the capital of the Hoysala kingdom. The Hoysala king, Ballala, surrendered a vast fortune as part of a truce and agreed to pay an annual tribute to the Delhi Sultanate.

From Dwarasamudra, Kafur advanced into the Pandya kingdom (also known as Ma'bar or the Tamil region). The Pandya kingdom was already embroiled in an internal conflict between two rival princes, Jatavarman Sundara Pandya and Jatavarman Vira Pandya. Sundara Pandya, who had killed his father to seize the throne but was then driven from the capital Madurai by Vira Pandya, sought Kafur's assistance. Kafur, aware of Vira Pandya's support for the Hoysala king Ballala III, agreed to intervene. In March 1311 (or late 1310), Kafur's forces attacked the Pandya kingdom, raiding numerous locations and extensively plundering the capital Madurai and sites like the Chidambaram Temple. While he acquired enormous treasures, he did not manage to decisively defeat the Pandya army or secure an agreement for annual tribute, leading some to consider this particular aspect of the expedition a failure. However, he advanced as far as Rameswaram, where he constructed a mosque and recited the Friday sermon (Khutba) in Alauddin's name.

Kafur returned to Delhi in triumph on October 18, 1311, with massive spoils of war, which, according to the chronicler Barani, included 612 elephants, a vast quantity of gold and jewels, and 20,000 horses. While the primary objective of these southern expeditions was to accumulate wealth, the acquisition of many subordinate states significantly expanded the Sultanate's sphere of influence.

2.3. Governorship of Devagiri

Despite his successful campaigns, maintaining annual tribute payments from the newly subjugated kingdoms proved challenging. After the death of King Ramachandra, his successor Singhana (or Shankaradeva) rebelled against the Khalji dynasty by discontinuing tribute payments. In 1313, likely at his own request, Kafur led another expedition to Devagiri. He subdued Singhana and fully annexed Devagiri into the Delhi Sultanate.

Kafur remained in Devagiri as governor of the newly annexed territory for two years, from 1313 to 1315. During his tenure, he administered the territory with a notable degree of sympathy and efficiency, ensuring stability and control. His governorship concluded when he was urgently recalled to Delhi in 1315, as Alauddin Khalji's health began to seriously deteriorate. Upon his recall, Kafur handed over the charge of Devagiri to Ayn al-Mulk Multani.

3. Political Rise and Influence

Malik Kafur's political influence grew immensely, culminating in his appointment to the highest administrative office and his consolidation of power during the Sultan's final years.

3.1. Appointment as Na'ib (Viceroy)

Malik Kafur eventually attained the prestigious position of Na'ib, effectively the viceroy of the Delhi Sultanate. While the precise date of this appointment is not definitively known, it signified his ascent to the apex of political power. During Alauddin Khalji's severe illness in 1315, Kafur was recalled from Devagiri to Delhi, where he assumed executive authority, effectively becoming the de facto ruler.

3.2. Relationship with Alauddin Khalji

Kafur's relationship with Alauddin Khalji was central to his rise. Captured in 1299, Kafur, described as an attractive man, quickly caught the Sultan's attention. A deep emotional bond developed between them, with Alauddin becoming infatuated with Kafur and distinguishing him above all other friends and helpers. Kafur held the highest place in the Sultan's esteem.

During Alauddin's final illness, the chronicler Ziauddin Barani (1285-1357) wrote a controversial description implying a homosexual relationship between the two: "In those four or five years when the Sultan was losing his memory and his senses, he had fallen deeply and madly in love with the Malik Naib. He had entrusted the responsibility of the government and the control of the servants to this useless, ungrateful, ingratiate, sodomite." Based on Barani's account, several scholars, including Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai, interpret their relationship as homosexual. However, historian Banarsi Prasad Saksena acknowledges Alauddin's infatuation in his later years but disputes the sexual nature of their bond, stating that "There was no element of homosexuality in Alauddin's character; and though Kafur was a eunuch, there was nothing wrong in Alauddin's relations with Kafur, apart from the fact that since Kafur, unlike all other officers, had no family or followers, the Sultan had a greater trust in him." Regardless of the exact nature of their personal relationship, Alauddin's profound trust in Kafur, partly due to Kafur's lack of independent family or followers who could pose a threat, allowed him to concentrate power in Kafur's hands during his declining health. Isami states that during Alauddin's final days, Kafur became the Sultanate's de facto ruler, controlling access to the ailing Sultan.

3.3. Political Maneuvering and Elimination of Rivals

As Alauddin Khalji's health declined, Kafur strategically consolidated his power. He capitalized on the Sultan's growing distrust of other officers, convincing Alauddin to purge several experienced administrators. This included abolishing the office of wazir (prime minister) and even executing the minister Sharaf Qa'ini, as Kafur viewed these officials as rivals.

Kafur's most ruthless actions were directed against potential threats to his authority. He perceived Alp Khan, an influential noble whose two daughters were married to Alauddin's sons, Khizr Khan (the heir apparent) and Shadi Khan, as a significant challenge. Kafur successfully convinced Alauddin to order Alp Khan's execution within the royal palace. Following this, he orchestrated Khizr Khan's banishment from court to Amroha, and subsequently his imprisonment in Gwalior. Khizr's brother, Shadi Khan, was also imprisoned. Stories circulated, even reaching Persia, that Khizr Khan, his mother, and Alp Khan had conspired to poison Alauddin to install Khizr as Sultan. While this narrative, corroborated to some extent by Ibn Battuta, may have been Kafur's propaganda to justify his actions, it effectively neutralized his rivals.

To formalize his position, Kafur convened a meeting of important officers at Alauddin's bedside. At this meeting, the six-year-old son of Alauddin, Shihabuddin, was declared the new heir apparent, with Kafur designated as his regent after Alauddin's death. Isami notes that Alauddin was too weak to speak during this crucial meeting, and his silence was taken as consent. Kafur also found allies in officers of non-Turkic origin, such as Kamal al-Din "Gurg", forming a counter-force against the established Turkic elite within the Sultanate.

4. Regency and Downfall

Malik Kafur's period as regent was brief and marked by intense political maneuvering and violence, ultimately leading to his own demise.

4.1. Assumption of Regency

Alauddin Khalji died on the night of January 4, 1316. Kafur promptly arranged for Alauddin's body to be brought from the Siri Palace and buried in his prepared mausoleum. A rumor, cited by Barani, even claimed that Kafur had murdered Alauddin.

The day after Alauddin's death, Kafur convened a meeting of key officers and nobles in the palace. There, he produced what he claimed was the late Sultan's will, which named Shihabuddin as successor while disinheriting Khizr Khan. Kafur then seated the young Shihabuddin on the throne as the new Sultan, effectively installing him as a puppet ruler under his regency. Kafur's regency was remarkably short, lasting approximately 35 days (Barani), one month (Isami), or 25 days (Firishta). During this period, he held a daily ceremonial court at the Hazar Sutun Palace within the Siri Fort. After a brief ceremony, he would send Shihabuddin to his mother and dismiss the courtiers. Kafur would then meet officers in his private chambers, issuing various orders and directing the ministries of revenue, secretariat, war, and commerce to uphold Alauddin's laws and regulations, requiring them to consult him on all policy matters.

4.2. Actions as Regent

To solidify his control, Kafur took several extreme measures. Before burying Alauddin, he removed the royal ring from the Sultan's finger. He gave this ring to his general, Sumbul, instructing him to march to Gwalior and seize control of the fort, using the ring as a symbol of royal authority. Kafur ordered Sumbul to send the fort's governor to Delhi and to return only after blinding Khizr Khan, who was imprisoned there. Sumbul carried out these orders and was rewarded with the title of Amir-i Hijab (Commander of the Faithful). On his very first day as regent, Kafur also ordered his barber to blind Shadi Khan, Khizr Khan's half-brother. These brutal acts against the royal family intensified resentment towards Kafur among the Turkic nobles.

Kafur further consolidated his power by stripping Alauddin's senior queen, known as Malika-i Jahan, of all her property and subsequently imprisoning her at Gwalior Fort. He also imprisoned Mubarak Shah, another adult son of Alauddin. According to Firishta, Kafur even married Alauddin's widow Jhatyapalli, Shihabuddin's mother, likely as a means to legitimize his power by becoming the new Sultan's stepfather.

Amidst these political purges, Alp Khan's murder had sparked a rebellion in Gujarat. Kafur had initially sent Kamal al-Din "Gurg" to suppress it. When Kamal al-Din was killed in Gujarat, Kafur recalled the Devagiri governor, Ayn al-Mulk Multani, to Delhi with his soldiers. Kafur then appointed Multani as the new governor of Gujarat, instructing him to suppress the ongoing rebellion there. The rebellion in Gujarat, however, could only be suppressed after Kafur's death.

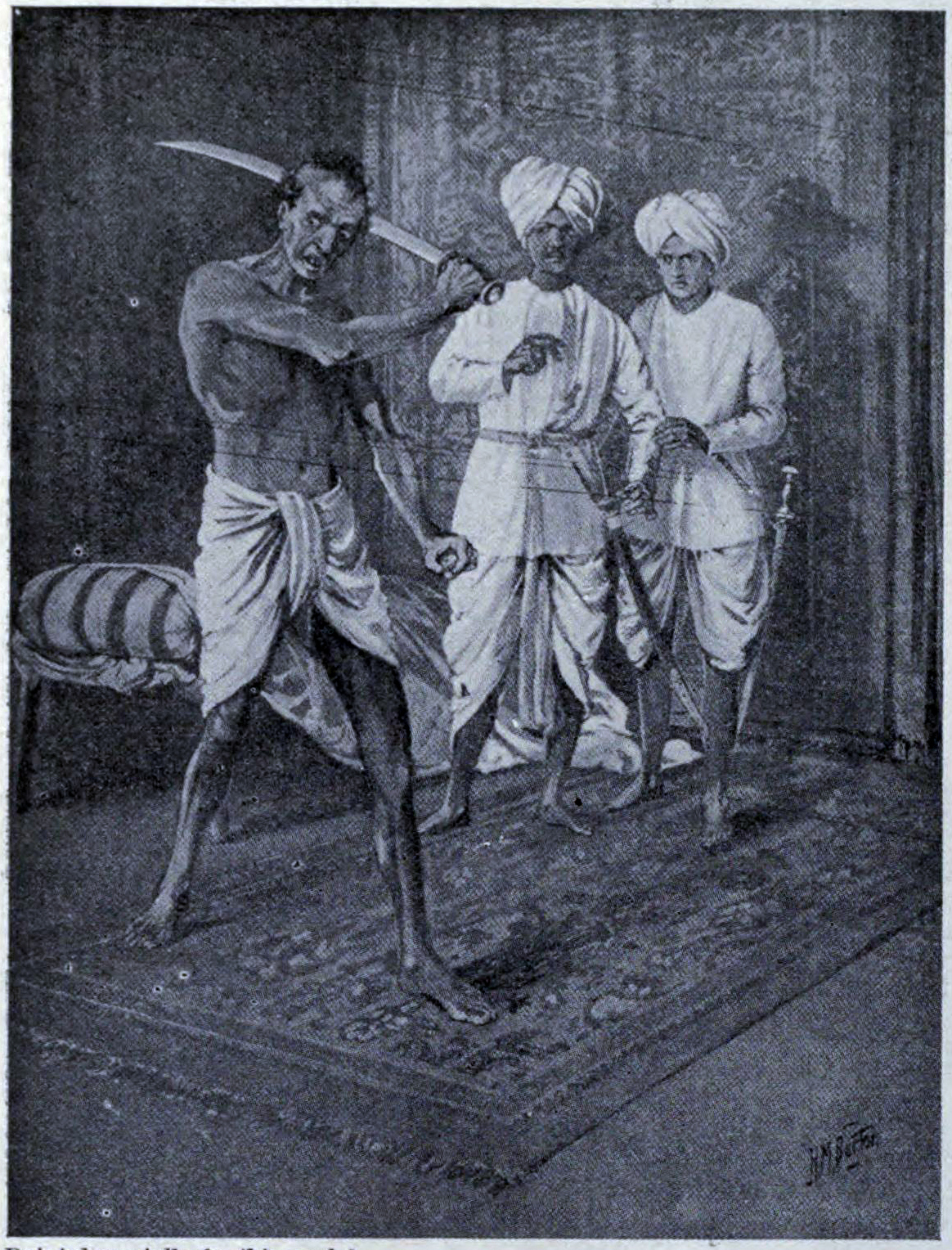

4.3. Assassination

Malik Kafur's reign as regent was abruptly ended in February 1316 by Alauddin Khalji's former bodyguards (paiks). These bodyguards deeply resented Kafur's ruthless actions against the family of their deceased master. Led by Mubashshir, Bashir, Saleh, and Munir, they conspired to assassinate him. When Kafur grew suspicious of a plot against him, he summoned Mubashshir to his chambers. Mubashshir, who retained the privilege of carrying arms in the royal quarters since Alauddin's time, wounded Kafur with his sword. His co-conspirators then entered the room, beheaded Kafur, and killed two or three gatekeepers who attempted to protect him.

Later accounts, such as one cited by Firishta, suggest that Kafur had sent some paiks to blind Mubarak Shah, but the captive prince bribed them with his jeweled necklace to kill Kafur instead. Another legend attributes Kafur's death to the prayers of his mother to the mystic Shaikhzada Jam. However, these are considered later fabrications. According to Barani's near-contemporary account, the paiks acted on their own initiative, motivated by their loyalty to the Khalji royal family.

Following Kafur's assassination, his killers freed Mubarak Shah, who was then appointed as the new regent. A few months later, Mubarak Shah seized full power by blinding the puppet Sultan Shihabuddin. The assassins, expecting high positions for their role in making Mubarak Shah king, were instead executed by him.

5. Legacy and Evaluation

Malik Kafur's legacy is a subject of contrasting historical interpretations, reflecting both his military genius and his controversial political actions.

5.1. Historical Evaluation

The chronicler Barani was highly critical of Kafur, portraying him as a "wicked fellow." However, modern historians like Abraham Eraly argue that Barani's criticisms are not entirely credible due to his significant prejudice against Kafur, likely stemming from Kafur's non-Turkic, Hindu origins and eunuch status.

Despite the moralistic criticisms, Kafur's military contributions were immense. He spearheaded the Delhi Sultanate's first successful military incursions into the far south of India, reaching as far as Madurai. These expeditions brought unprecedented amounts of wealth, including elephants, gold, and jewels, back to Delhi. This influx of riches significantly contributed to the cultural and economic development of the Sultanate under Alauddin. While his primary objective was the acquisition of wealth rather than permanent conquest, his campaigns established the Sultanate's dominance over many new tributary states, effectively expanding its influence over a vast territory.

Kafur's rise from a slave and a Hindu convert to a powerful general and regent was remarkable for his time. He was not the first Indian convert to achieve high political office in the Sultanate; Imad-ud-din Raihan during the Slave Dynasty had also briefly held the regency, displacing Ghiyasuddin Balban. However, Kafur's ruthless political maneuvering, especially during Alauddin's illness, where he systematically eliminated rivals and blinded princes, demonstrates a readiness to commit heinous acts to secure power. His actions as regent, though brief, undermined the stability of the succession and highlight the brutal realities of power struggles within the Sultanate. From a perspective emphasizing social equity and human rights, his treatment of the royal family, particularly the blinding of young princes, stands as a stark example of the cruelty he employed to maintain his grip on power. His military achievements, while impressive, are thus tempered by the morally dubious nature of his political ascent and short-lived regency.

5.2. Tomb

The exact location of Malik Kafur's grave remains unknown today. However, his mausoleum existed in the 14th century, as it was noted to have been repaired by Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq (r. 1351-1388). Firuz Shah's autobiography, Futuhat-i-Firuzshahi, mentions this act, stating: "Tomb of Malik Taj-ul-Mulk Kafur, the great wazir of Sultan Ala-ud-din. He was a most wise and intelligent minister, and acquired many countries, on which the horses of former sovereigns had never placed their hoofs, and he caused the Khutba of Sultan Ala-ud-din to be repeated there. He had 52,000 horsemen. His grave had been levelled with the ground, and his tomb laid low. I caused his tomb to be entirely renewed, for he was a devoted and faithful subject." This account from Firuz Shah provides a contrasting view to Barani's, emphasizing Kafur's wisdom, intelligence, and loyalty as a minister and a successful military leader who expanded the Sultanate's reach.

6. Popular Culture

Malik Kafur's historical figure has found its way into modern popular culture, particularly in Indian cinema.

6.1. Portrayal in Film

In the 2018 Bollywood film Padmaavat, Malik Kafur is portrayed by actor Jim Sarbh. The film, a fictionalized historical drama, depicts Kafur as a close confidante and general of Alauddin Khalji, with an emphasis on their complex and often depicted as homosexual relationship.