1. Overview

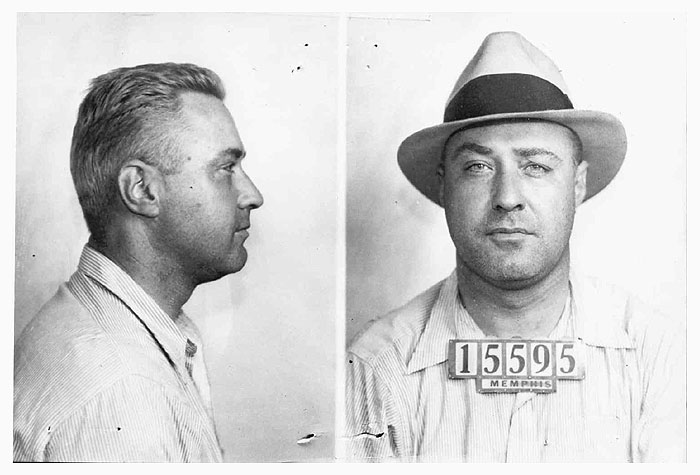

George Kelly Barnes (July 18, 1895 - July 18, 1954), widely known by his notorious nickname "Machine Gun Kelly", was an American gangster from Memphis, Tennessee, who rose to prominence during the Prohibition era. He engaged in a diverse range of criminal activities, including bootlegging, armed robbery, and kidnapping. His moniker was derived from his preferred weapon, the Thompson submachine gun. Kelly is most infamously recognized for the July 1933 kidnapping of oil tycoon Charles F. Urschel, from whom he and his gang extorted a ransom of 200.00 K USD. The meticulous evidence left by Urschel proved instrumental in the subsequent FBI investigation, which ultimately led to Kelly's arrest in Memphis on September 26, 1933. His case was pivotal in the development of federal law enforcement, marking the first major case solved by J. Edgar Hoover's FBI and contributing to the popularization of the term "G-Men".

2. Early Life and Background

George Kelly Barnes was born on July 18, 1895, into a wealthy family in Memphis, Tennessee. He experienced a traditional upbringing and reportedly had a childhood free of significant trouble. He attended Idlewild Middle School before progressing to Central High School, one of Memphis's oldest public high schools.

In 1917, Kelly enrolled at Mississippi State University to study agriculture. However, his academic career was marked by difficulties; he was considered a poor student, with his highest grade being a C+ for physical hygiene, and he frequently encountered trouble with the faculty, spending much of his time working off demerits. During his time at the university, Kelly met Geneva Ramsey, with whom he quickly fell in love. He abruptly decided to leave school to marry Ramsey, and they had two children. Despite his family's wealth, Kelly did not rely on their financial support, instead working as a taxi driver and other odd jobs to make ends meet. However, his father's disapproval of Ramsey and persistent financial struggles ultimately led to the breakdown of their marriage.

3. Criminal Career

George "Machine Gun" Kelly's criminal career escalated significantly during the Prohibition era, transitioning from petty crimes to high-stakes kidnappings that eventually led to his downfall.

3.1. Early Criminal Activities and Relationship with Kathryn Thorne

During the Prohibition era of the 1920s and 1930s, Kelly ventured into bootlegging, operating both independently and with associates. After several confrontations with local police in Memphis, he decided to leave the city with a new girlfriend. To evade law enforcement and protect his family, he legally changed his name to George R. Kelly. He continued to engage in small-scale crimes and bootlegging activities.

In 1928, Kelly was arrested in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for smuggling liquor onto a Native American Reservation. He was sentenced to three years at Leavenworth Penitentiary, Kansas, beginning his incarceration on February 11, 1928. He reportedly maintained a reputation as a model inmate and was granted an early release.

Shortly after his release, Kelly married Kathryn Thorne, an experienced criminal who played a crucial role in shaping his notorious image. Kathryn purchased Kelly's first Thompson submachine gun and, despite his initial disinterest in weapons, insisted that he practice target shooting in rural areas. She also made significant efforts to popularize his name within underground crime circles, with some historians crediting her with coining the nickname "Machine Gun Kelly."

According to Persons in Hiding, a 1938 book by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Kelly, along with Kathryn and Eddie Doll, was involved in the kidnapping of a wealthy manufacturer in South Bend, Indiana, for a 50.00 K USD ransom. Although Hoover did not name the victim in his book or related 1937 American Magazine articles, local newspaper reports assumed he was referring to the January 26, 1932, abduction of Howard Arthur Woolverton. Woolverton was released unharmed within 24 hours, and while the crime was largely forgotten in subsequent decades, it was widely reported at the time as a significant turning point in America's escalating kidnapping epidemic. The New York Daily News described Woolverton's abduction as "spectacular" and asserted that "for brazen audacity (it) has no parallel," suggesting such crimes "represent a challenge to organized society." This incident revived discussions in Congress regarding the Lindbergh Law and prompted several nationally distributed newspaper projects that analyzed the growing crime wave, portraying kidnapping as a threat to every American. These projects, including a 16-part series in the Daily News, were prepared for publication just days before the March 1, 1932, kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr., thereby framing the infant's abduction not as an isolated incident but as part of a pervasive national problem.

3.2. The Urschel Kidnapping

The July 1933 kidnapping of wealthy Oklahoma City resident Charles F. Urschel and his friend Walter R. Jarrett proved to be the pivotal event that led to George "Machine Gun" Kelly's downfall, marking a significant moment in federal law enforcement history.

3.2.1. Kidnapping and Ransom Demand

On July 20, 1933, Kelly and his accomplices abducted Charles F. Urschel and Walter R. Jarrett. Despite their careful efforts during the crime, they inadvertently left behind crucial evidence, including fingerprints. The Kellys demanded a ransom of 200.00 K USD for Urschel's release. During his captivity, Urschel was held at the farm belonging to Kathryn's mother and stepfather.

3.2.2. Evidence and Investigation

While blindfolded during his abduction, Charles F. Urschel ingeniously gathered information about his surroundings. He made note of various background sounds, meticulously counted footsteps, and intentionally left fingerprints on accessible surfaces. This evidence proved invaluable to the FBI's investigation. Based on the sounds Urschel recalled hearing while held hostage, FBI agents were able to conclude that he had been held in Paradise, Texas.

A subsequent investigation conducted in Memphis revealed that the Kellys were residing at the home of J. C. Tichenor. This discovery prompted the immediate dispatch of special agents from Birmingham, Alabama, to Memphis to apprehend the fugitives.

3.2.3. Arrest

In the early morning hours of September 26, 1933, a raid was conducted at J. C. Tichenor's residence in Memphis. George and Kathryn Kelly were taken into custody by FBI agents and Memphis police officers Thomas Waterson and Sergeant William Raney.

A widely circulated account claims that Kelly, caught unarmed, allegedly shouted, "Don't shoot, G-Men! Don't shoot, G-Men!" as he surrendered. However, this version of events appears to be a media myth that emerged months after the actual arrest. Another narrative suggests Kelly had a pistol in his hand but surrendered when a shotgun was aimed at his heart, stating, "I've been expecting you." The FBI's earliest official account of the event, written within three to five days of Kelly's arrest, states that Agent William Asbury "Ash" Rorer observed Kelly in the front bedroom, hands raised, covered by Memphis Police Sergeant William Raney, with no reported speech from Kelly. Recent research, based on interviews with the arresting officers, indicates that Kathryn Kelly may have been the one to coin the term "G-Men" during the raid, reportedly telling George, "They won't let us get out of here alive." Despite this, the FBI allegedly perpetuated the "G-Men" myth to enhance its public image.

Coincidentally, the arrest of the Kellys was overshadowed by the escape of ten inmates, including all future members of the Dillinger gang, from the penitentiary in Michigan City, Indiana, on the very same night.

3.3. Trial and Sentencing

The federal trial for the Urschel kidnapping was held at the Post Office, Courthouse, and Federal Office Building in Oklahoma City, with Judge Edgar S. Vaught presiding. On October 12, 1933, both George and Kathryn Kelly were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. Kathryn Kelly and her mother, who was also implicated in the kidnapping, denied all charges but were eventually released from prison in 1958.

Further investigation in Coleman, Texas, revealed that Cassey Earl Coleman and Will Casey had housed and protected the Kellys. Coleman had also assisted George Kelly in storing 73.25 K USD of the Urschel ransom money on his ranch. This money was discovered by Bureau agents in a cotton patch on Coleman's ranch in the early morning hours of September 27. Coleman and Casey were both indicted in Dallas, Texas, on October 4, 1933, facing charges of harboring a fugitive and conspiracy. On October 17, 1933, Coleman received a sentence of one year and one day after pleading guilty, while Casey, following a trial and conviction, was sentenced to two years in the United States Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas.

The Urschel kidnapping and the subsequent trials were historically significant for several reasons:

- They marked the first federal criminal trials in the United States where film cameras were permitted.

- They were the first kidnapping trials conducted after the passage of the Lindbergh Law, which designated kidnapping as a federal crime.

- It was the first major case successfully solved by J. Edgar Hoover's newly empowered FBI.

- It represented the first prosecution in which defendants were transported by airplane.

4. Imprisonment

George "Machine Gun" Kelly spent the remaining 21 years of his life incarcerated. He was initially sent to Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary, where he was inmate number 117. During his time at Alcatraz, he acquired the nickname "Pop Gun Kelly." According to fellow inmate Dale Stamphill, this nickname originated because Kelly "told big fish stories. The cons called him 'Pop Gun Kelly' after cork guns that were popular with kids...the guys didn't take him seriously...." This perception likely stemmed from his exaggerated tales and the fact that, contrary to the brutal gangster image cultivated by his wife, the media, and the FBI, Kelly was a model prisoner. He spent 17 years at Alcatraz, working in the prison industries and continuing to boast and exaggerate his past escapades to other inmates. In 1951, he was quietly transferred back to Leavenworth Penitentiary.

5. Death

George "Machine Gun" Kelly died of a heart attack at Leavenworth Penitentiary on July 18, 1954, the day before his 60th birthday. He was buried at Cottondale Texas Cemetery in Cottondale, Texas, within Kathryn Kelly's stepfather's family plot. His small headstone is marked "George B. Kelley 1954." Kathryn Kelly was released from prison in 1958 and lived in relative anonymity in Oklahoma under the assumed name "Lera Cleo Kelly" until her death in 1985 at the age of 81.

6. Assessment and Impact

George "Machine Gun" Kelly's criminal career, particularly the Urschel kidnapping, left a lasting legacy on American law enforcement and popular culture, influencing the development of federal agencies and inspiring various media portrayals.

6.1. Historical Significance and Myth

The Urschel kidnapping case had a profound impact on the development of federal law enforcement in the United States. It was the first major case successfully solved by the FBI under Director J. Edgar Hoover, significantly boosting the agency's reputation and establishing its effectiveness in combating organized crime across state lines. The case also played a crucial role in the popularization of the term "G-Men" to refer to FBI agents. While the widely reported story of Kelly shouting "Don't shoot, G-Men!" upon his arrest is largely considered a media myth, some accounts suggest his wife, Kathryn Kelly, may have actually coined the term during the raid. Regardless of its precise origin, the FBI strategically utilized this "G-Men" narrative to enhance its public image and assert its authority. Furthermore, the Urschel trials were groundbreaking as the first federal criminal proceedings in the United States to permit the use of film cameras, setting a precedent for media coverage of high-profile cases. The case also highlighted the effectiveness of the recently passed Lindbergh Law, which made kidnapping a federal crime, and marked the first instance of defendants being transported by airplane for prosecution.

6.2. Portrayal in Popular Culture

George "Machine Gun" Kelly's life and crimes have been depicted in various forms of media, cementing his place in American popular culture:

- Films:** He has been portrayed in movies such as Machine-Gun Kelly (1958), The FBI Story (1959), and Melvin Purvis: G-Man (1974).

- Literature:** Crime novelist Ace Atkins' 2010 book Infamous is based on the Urschel kidnapping and features both George and Kathryn Kelly. He is also one of the main characters, alongside Pretty Boy Floyd and Baby Face Nelson, in the comic book series Pretty, Baby, Machine.

- Music:** The contemporary American rapper Colson Baker adopted his stage name from the notorious gangster.