1. Overview

Lucretia (Lucretialoo-KREE-shəLatin), also anglicized as Lucrece (LucreziaItalian in Italian), is a pivotal figure in ancient Roman tradition. Her story, centered on her rape by Sextus Tarquinius, the son of the tyrannical last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, and her subsequent suicide, served as the immediate catalyst for a rebellion that led to the overthrow of the Roman monarchy and the establishment of the Roman Republic. This transition, dated by various historians to around 509 BC or 508 BC, marked a fundamental shift in Roman governance from a kingdom to a republic.

While no contemporary sources for Lucretia's life or the incident itself exist, her narrative is primarily derived from accounts written centuries later by Roman historians such as Livy and Greco-Roman historians like Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Despite slight variations in specific details across these historical records, the core events remain consistent. Modern scholarship often categorizes Lucretia's story as part of Roman mythohistory, recognizing its function as a foundational myth that explains significant historical change through an act of violence against women. Lucretia herself became an enduring symbol of Roman virtue, chastity, and a powerful emblem of resistance against tyranny, deeply influencing Western literature and art for centuries.

2. Early Life and Background

Lucretia's early life and background are primarily described through the lens of her exemplary Roman virtues and her family's standing, setting the stage for her tragic role in Roman history.

2.1. Family and Marriage

Lucretia was the daughter of Spurius Lucretius, a prominent Roman magistrate who would later serve as the prefect of Rome and the first interrex of the Roman Republic. She was married to Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, a kinsman of the royal Tarquin family. Their union was widely celebrated and depicted in ancient sources as the epitome of an ideal Roman marriage, characterized by profound mutual devotion and unwavering faithfulness.

2.2. Reputation and Virtues

Ancient historians, particularly Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, consistently portray Lucretia as an exemplar of traditional Roman womanhood. She was celebrated for her exceptional "beauty and purity," embodying the highest Roman standards of chastity, domesticity, and moral character. Her virtues were highlighted in a famous anecdote: during the Roman siege of Ardea, a debate arose among the sons of King Lucius Tarquinius Superbus and their kinsmen, including Lucius Junius Brutus and Collatinus, regarding whose wife best embodied sophrosyne, an ideal of superb moral and intellectual character.

To settle the dispute, the men decided to visit their homes unannounced. While the wives of the royal family were found feasting and socializing, Lucretia was discovered at home, alone, diligently working with her wool alongside her maids. This scene, demonstrating her unwavering devotion to her husband and her commitment to domestic duties, earned her the "palm of victory" in their wager. This depiction further solidified her image as a role model for Roman girls, emphasizing her dedication to her husband and her quiet, virtuous life.

3. The Rape Incident

The rape of Lucretia is the central event that precipitates the dramatic political upheaval in Rome, with historical accounts detailing the circumstances and the threats that compelled her compliance.

3.1. Background and Course of the Incident

The incident is generally placed around 509 BC or 508 BC. During the Roman siege of Ardea, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome, dispatched his son, Sextus Tarquinius, on a military errand to Collatia. Sextus was received with great hospitality at the governor's mansion, which was the home of Lucretia and her husband, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus. Lucretia's father, Spurius Lucretius, who was the prefect of Rome, ensured that Sextus was treated with all due respect as a guest of his high rank.

Consumed by lust after witnessing Lucretia's exemplary virtue during the earlier wager among the men, Sextus Tarquinius returned to Collatia alone. Later that night, he secretly entered Lucretia's bedroom, carefully avoiding the slaves who were sleeping near her door. Upon her awakening, he revealed his identity and presented her with a horrifying choice: she could submit to his rape, with the false promise that she would become his wife and future queen, or he would kill her and one of her male slaves, placing their naked bodies together to fabricate a scene of adulterous sex. This latter threat, which would bring irreparable shame and dishonor upon Lucretia and her esteemed family, ultimately compelled her to yield to his demands.

An alternative account suggests that Sextus returned from the camp a few days later with a single companion, ostensibly to accept Collatinus's earlier invitation to visit. He was lodged in a guest bedroom. During the night, he entered Lucretia's room while she lay naked in her bed and began to wash her belly with water, which woke her. Tarquin then attempted to convince Lucretia to be with him, employing "every argument likely to influence a female heart." However, Lucretia remained steadfast in her devotion to her husband, even when Tarquin threatened her life and honor, before he ultimately raped her.

3.2. Differences in Historical Records

While the core narrative of Lucretia's rape is consistent across ancient sources, specific details and the precise sequence of events vary among historians, underscoring the story's nature as a foundational myth rather than a strictly documented historical event.

Livy's account emphasizes the initial wager among the men regarding their wives' virtues, which directly leads to the observation of Lucretia's domesticity and sets the stage for Tarquin's lust. Livy also explicitly details the specific threat of Lucretia being found with a slave, highlighting it as the ultimate factor that forces her compliance.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus provides a similar narrative but sometimes includes slightly different chronological details, such as setting the date of Lucretia's death around 508 BC based on Athenian archonship, a detail that helps contextualize the subsequent revolution. The Japanese and Thai sources also mention the date of the event as 509 BC.

Although not detailed in the provided snippets for the rape itself, Cassius Dio's version is noted for its distinct rendition of Lucretia's dying plea for vengeance, which differs from Livy's. These discrepancies indicate that while the event served a crucial narrative and symbolic function in Roman history, the exact historical facts were subject to interpretation and emphasis by various ancient historians.

4. Suicide and its Aftermath

Lucretia's decision to commit suicide following the rape is a pivotal moment that transforms a personal tragedy into a public demand for justice, culminating in the oath that ignites the Roman revolution.

4.1. Decision and Execution of Suicide

Overwhelmed by profound shame and a sense of irreparable dishonor after the rape, Lucretia resolved to take her own life, believing it to be the only way to cleanse her family's honor and set an example of virtue. Ancient accounts detail her final actions with slight variations, each emphasizing her resolve.

According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, the day after the incident, Lucretia dressed in black and went to her father's house in Rome. There, she cast herself down in the supplicant's position, weeping before her father, Spurius Lucretius, and her husband, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus. She insisted on summoning witnesses before she would recount the traumatic event. After tearfully disclosing that Sextus Tarquinius had raped her, she implored them for vengeance, a plea that, given her father's position as chief magistrate of Rome, carried immense weight and could not be ignored. As the men deliberated on the appropriate course of action, Lucretia, without hesitation, drew a concealed poignard and plunged it into her heart. She died in her father's arms, as the women present lamented her tragic death.

Livy's account portrays Lucretia acting with remarkable composure and swiftness. She did not travel to Rome but instead sent for her father and husband, instructing each to bring one trusted friend as a witness. Her father arrived with Publius Valerius Publicola, and her husband brought Lucius Junius Brutus from the camp at Ardea. Upon finding Lucretia in her room, she confessed the rape. The men, attempting to console her, stated, "it is the mind that sins, not the body, and where there has been no consent there is no guilt." However, Lucretia, seeking not just solace but justice, exacted a solemn oath of vengeance from them: "Pledge me your solemn word that the adulterer shall not go unpunished." Immediately after securing this pledge, she drew a dagger and stabbed herself through the heart.

Cassius Dio's version of her dying words emphasizes her call to action for the men: "And, whereas I (for I am a woman) shall act in a manner which is fitting for me: you, if you are men, and if you care for your wives and children, exact vengeance on my behalf and free your selves and show the tyrants what sort of woman they outraged, and what sort of men were her menfolk!" She then promptly plunged the dagger into her chest, dying instantly.

4.2. Reactions to Death

Lucretia's dramatic suicide had an immediate and profound impact on those present, transforming personal grief into a powerful catalyst for political revolution. Collatinus was overcome with despair, holding his dying wife, kissing her, and speaking her name.

It was Lucius Junius Brutus who seized the moment, channeling the collective horror and sorrow into a powerful call for action. Brutus, who had been feigning foolishness to protect himself from the tyrannical King Tarquinius Superbus, revealed his true, politically astute nature. He was a kinsman of the Tarquins through his mother, Tarquinia, daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, but his paternal lineage as a Junius allowed him to advocate for the Tarquins' exile without fear for himself.

According to Dio, Brutus called the grieving party to order, explaining his previous pretense. He then proposed the immediate expulsion of the Tarquin family from Rome. Grasping the bloody dagger that Lucretia had used, Brutus swore a solemn oath by Mars and all the other gods to overthrow the dominion of the Tarquinii. He vowed never to reconcile with the tyrants, to tolerate no one who would, and to pursue the tyranny and its supporters with unrelenting hatred until his death. He invoked a curse upon himself and his children if he were to violate this oath, wishing them the same fate as Lucretia. He then passed the dagger around, and each mourner, including Lucretia's father and husband, swore the same oath, pledging to avenge her and liberate Rome from tyranny. Livy records Brutus's oath as: "By this blood-most pure before the outrage wrought by the king's son-I swear, and you, O gods, I call to witness that I will drive hence Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, together with his cursed wife and his whole blood, with fire and sword and every means in my power, and I will not suffer them or anyone else to reign in Rome." This collective oath marked the decisive turning point, transforming a private tragedy into a public demand for justice and political change.

5. Establishment of the Roman Republic

Lucretia's tragic death served as the direct catalyst for the overthrow of the Roman monarchy and the foundation of the Roman Republic, initiating a profound transformation in Roman governance.

5.1. Overthrow of Monarchy and Proclamation of Republic

The collective oath sworn over Lucretia's body immediately galvanized the revolutionaries. The newly formed committee, led by Lucius Junius Brutus, paraded Lucretia's bloody corpse through the streets of Collatia and then to the Roman Forum. Her body was prominently displayed as a stark and visceral reminder of the dishonor and tyranny committed by the royal family.

At the Forum, a large crowd gathered, and the revolutionaries, with magistrates among them to maintain order, began to enlist an army to abolish the monarchy. Brutus, leveraging his position as Tribune of the Celeres (a minor magistracy with religious duties that allowed him to summon the curiae, an organization of patrician families), transformed the assembled crowd into an authoritative legislative assembly. He delivered one of the most impactful speeches in ancient Roman history.

In his address, Brutus first revealed his long-held pretense of foolishness, explaining it as a necessary deception to protect himself from the oppressive king. He then launched a scathing indictment against King Lucius Tarquinius Superbus and his family. He highlighted Tarquin's brutal rape of Lucretia, whose body was visible to all, as well as the king's overall tyranny and the forced labor imposed on the plebeians for public works like ditches and sewers. Brutus also recalled that Superbus had ascended to the throne by murdering Servius Tullius, the previous king and his own father-in-law, solemnly invoking the gods as avengers of murdered parents. He noted that the king's wife, Tullia, likely a witness to the proceedings from her nearby palace, had fled in fear to the camp at Ardea.

Brutus then initiated a debate on the future form of Roman government, with many patricians contributing. The consensus led to a proposal for the banishment of the Tarquins from all Roman territories and the establishment of an interrex to nominate new magistrates and oversee a ratification election.

5.2. Early Republican Governance

The immediate outcome of the revolution was the decision to replace the monarchy with a republican form of government. This new system initially featured two consuls who would execute the will of a patrician senate, serving as a temporary measure while more detailed governmental structures were considered. Brutus, despite his royal lineage, publicly renounced any claim to the throne.

A final vote by the curiae swiftly ratified this interim constitution. Spurius Lucretius, already the city's prefect, was elected as the first interrex. He then nominated Brutus and Collatinus as the first two consuls, a choice ratified by the curiae. To secure the broader assent of the Roman populace, Lucretia's body was again paraded through the streets, summoning the plebeians to a legal assembly in the Forum. There, Brutus delivered another constitutional speech, emphasizing that Tarquinius had neither gained power legitimately nor exercised it honorably, surpassing "all the tyrants the world ever saw." He declared the patricians' decision to depose him and sought the plebeians' assistance in achieving national liberty. A general election was held, and the vote overwhelmingly favored the establishment of the Republic, officially ending the monarchy.

In subsequent years, the powers previously held by the king were systematically divided among various elected magistracies, laying the foundation for the complex system of the Roman Republic. This constitutional tradition, born from Lucretia's tragedy, profoundly influenced later Roman political thought, preventing figures like Julius Caesar and Augustus from formally accepting a crown and instead requiring them to consolidate power through a confluence of existing republican offices. The legacy of an elective, rather than hereditary, head of state persisted even into the Holy Roman Empire, over 2,300 years later.

6. Historical Evaluation and Debate

The historical evaluation of Lucretia's story involves examining its factual basis and its profound significance as a foundational myth that shaped Roman identity and values.

6.1. Debate on Historical Reality

The historical reality of Lucretia's story is a subject of ongoing scholarly debate. There are no contemporary sources for Lucretia's life or the events surrounding her rape and suicide. The primary accounts available come from Roman historians like Livy and Greco-Roman historians such as Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who wrote approximately 500 years after the purported events (circa 510-508 BC). These later accounts, while consistent in their broad outline, exhibit variations in specific details, suggesting that the narrative may have evolved over time.

While the evidence points to the probable historical existence of a woman named Lucretia and an event that played a critical role in the downfall of the monarchy, the precise details of the rape and suicide are debatable and vary depending on the writer. The historical existence of other figures from the early Roman Republic is also often questioned. Modern scholarship often considers Lucretia's narrative to be part of Roman mythohistory. This term acknowledges that while the story may contain elements of historical truth, it also functions as a foundational myth, shaped and elaborated upon to explain significant social and political changes in Roman history.

6.2. Mythohistorical Interpretation

In Roman mythohistory, Lucretia's story serves a crucial narrative function, much like the Rape of the Sabine Women, in explaining profound historical transformations through the recounting of violence against women by men. Her narrative is interpreted as a powerful allegory for the Roman people's resistance against tyranny and their transition from a monarchy to a republic.

Lucretia herself became a potent symbol of Roman virtue, particularly chastity and honor. Her suicide, rather than being an act of despair, is portrayed as a supreme sacrifice to preserve her honor and, by extension, the honor of Rome. It demonstrated that the shame of the act itself was less tolerable than death, thereby justifying the extreme measures taken by her family and the Roman populace. The story thus reinforces core Roman values, such as the importance of personal virtue, the sanctity of family honor, and the abhorrence of tyrannical rule. It provided a moral justification for the revolution, framing the overthrow of the Tarquin kings not merely as a political coup but as a righteous act of vengeance against an unbearable injustice, solidifying the ideals upon which the Roman Republic was founded.

7. Influence in Literature and Art

Lucretia's story has had an enduring impact across various artistic and literary traditions, serving as a powerful and adaptable narrative that has been reinterpreted as a symbol of virtue, tragedy, and political ideals from antiquity to the modern era. Her tale is considered one of the "foundational myths of Western culture" that deals with sexual violence against women.

7.1. Literary Works

The earliest surviving full historical treatment of Lucretia's story is found in Livy's Ab Urbe Condita Libri (circa 25-8 BC). Livy's account emphasizes the virtue of Lucretia, who is found weaving at home, in contrast to the perceived laxity of Etruscan noblewomen who were feasting. Ovid also recounts the story in Book II of his Fasti, published in 8 AD, focusing on the bold and overreaching character of Tarquin.

In the early Christian era, St. Augustine utilized Lucretia's figure in The City of God (published 426 AD) to argue that Christian women who had been raped during the sack of Rome were not dishonored, thereby defending their honor even if they did not commit suicide. This interpretation was echoed by Christine de Pizan in her City of Ladies, where she defended women's sanctity.

The Middle Ages saw Lucretia's story become a popular moral tale. Dante features Lucretia in Canto IV of his Inferno, placing her in Limbo among the noble Romans and other "virtuous pagans." Geoffrey Chaucer retells the myth in The Legend of Good Women, largely following Livy's narrative but adding details like Lucretia summoning her mother and attendants alongside her father and husband. John Gower's Confessio Amantis (Book VII) includes "The Tale of the Rape of Lucrece," and John Lydgate's Fall of Princes recounts the fall of Tarquin, Lucretia's rape and suicide, and her final speech.

The Renaissance brought renewed interest. William Shakespeare's long narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece (1594) extensively draws on Ovid's treatment, exploring Lucretia as a moral agent grappling with the aftermath of the rape and her unwillingness to yield to her rapist. Shakespeare also alludes to her in several plays, including Titus Andronicus, As You Like It, Twelfth Night (where Malvolio authenticates a letter by spotting Olivia's Lucrece seal), Macbeth, and Cymbeline. Niccolò Machiavelli's comedy La Mandragola is loosely based on the story. The poem "Appius and Virginia" by John Webster and Thomas Heywood explicitly links Lucretia with Verginia as women whose "ruins have rais'd declining Rome." Thomas Heywood also wrote a play titled The Rape of Lucretia in 1607.

In later periods, Samuel Richardson's 1740 novel Pamela features a discussion of Lucretia's story, where the protagonist Pamela corrects Mr. B's misinterpretation. Colonial Mexican poet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz mentions Lucretia in her "Redondillas," a commentary on prostitution. In 1769, doctor Juan Ramis wrote a neoclassical tragedy Lucrecia in Catalan. The 1932 Broadway play Lucrece, starring legendary actress Katharine Cornell, was largely performed in pantomime. More recently, Donna Leon's 2009 novel About Face references the tale from Ovid's Fasti.

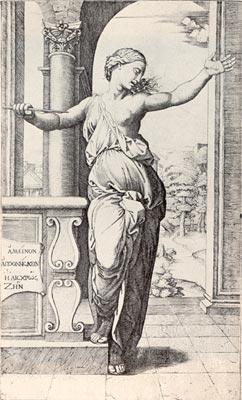

7.2. Artistic Representations

Lucretia's suicide, and sometimes the rape itself, has been an enduring and popular subject for visual artists since the Renaissance. The depiction often features Lucretia alone at the moment of her suicide, clutching a dagger, or the dramatic scene of the rape. In such portrayals, Lucretia's clothing is typically loosened or absent, while Tarquin remains clothed.

Prominent artists who depicted Lucretia include Titian (notably Tarquin and Lucretia), Rembrandt (who painted her multiple times, including Lucretia in 1664 and 1666), Albrecht Dürer (The Suicide of Lucretia), Raphael, Sandro Botticelli (The Story of Lucretia, depicting three scenes: the rape, Brutus arousing the people, and the suicide), Jörg Breu the Elder, Johannes Moreelse, Artemisia Gentileschi (known for her powerful depictions of female figures, including a version of the rape), Damià Campeny, Eduardo Rosales, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Lorenzo Lotto (Portrait of a Woman as Lucretia), and Andrea Casali.

Her story belongs to a group of subjects featuring women from legend or the Bible who were either powerless victims, like Susanna and Verginia, or who could only escape their dire situations through suicide, such as Dido of Carthage and Lucretia herself. These themes often contrasted with or complemented the "Power of Women" motif, which depicted female dominance or violence against men, a popular subject in Northern Renaissance art. A less common artistic subject is Lucretia spinning with her ladies, as seen in a series of four engravings by Hendrick Goltzius, which also includes a banquet scene.

7.3. Music and Other Arts

Lucretia's tragic story has also found expression in musical compositions and other artistic mediums. Benjamin Britten's 1946 opera The Rape of Lucretia, with a libretto by Ronald Duncan adapted from André Obey's 1931 play Le Viol de Lucrèce, is a notable example, premiering at Glyndebourne. Ernst Krenek also set Emmet Lavery's libretto Tarquin (1940), offering a contemporary setting of the tale. The baroque lutenist Jacques Gallot (died circa 1690) composed allemandes titled "Lucrèce" and "Tarquin." Georg Friedrich Händel composed a cantata titled "Oh, Eternal Gods" based on her story.

In popular music, the Scottish musician Momus released a song titled "The Rape of Lucretia" in 1989. The American thrash metal band Megadeth included a song named "Lucretia" on their 1990 album Rust In Peace; while not directly narrating her story, the name served as a muse for frontman Dave Mustaine's journey to sobriety.

8. Related Topics

- Lucretia gens: The Roman gens (family name) to which Lucretia belonged, known for its ancient origins and prominent members in the early Republic.

- Verginia: Another Roman woman whose tragic story of sexual assault and death, occurring later in the Republic, similarly sparked a popular uprising against the decemviri and led to significant political reforms. Her narrative often parallels Lucretia's in its symbolic role as a catalyst for liberty.

- The Rape of the Sabine Women: An earlier foundational myth in Roman history, describing the abduction of Sabine women by the first Romans to populate their new city. While also involving violence against women, this story is interpreted differently, focusing on the founding and integration of Rome's population rather than the overthrow of tyranny.

- Matter of Rome: A term used to describe the body of legendary and historical material concerning ancient Rome, particularly its founding and early history, which served as a source for medieval and Renaissance literature. Lucretia's story is a key component of this "matter."