1. Overview

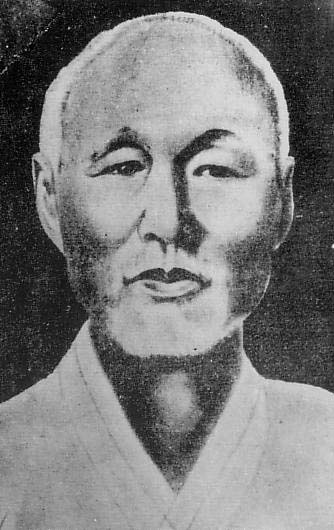

Kang Woo-kyu (강우규Kang Woo-kyuKorean, April 20, 1855 - November 29, 1920) was a Korean medicine doctor and a prominent independence activist during the Japanese colonial period. He is widely remembered for his daring assassination attempt against Saitō Makoto, the newly appointed Governor-General of Korea, at Seoul Station in 1919. Although the bombing failed to harm Saitō, it caused numerous casualties among Japanese officials and civilians, an act which some contemporary Japanese sources described as "terrorism" while Korean sources lauded it as a significant act of resistance. Kang's unwavering defiance during his trial and execution, coupled with his final words emphasizing the importance of national education, cemented his legacy as a powerful symbol of resistance and a source of inspiration for future generations of independence fighters.

2. Life and Career

Kang Woo-kyu's early life was marked by his studies in traditional medicine and Confucianism, which later transitioned into a career as a doctor and businessman. His deep-seated patriotism, however, led him to abandon his established life and dedicate himself to the Korean independence movement, first within Korea and later from exile.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Kang Woo-kyu was born on April 20, 1855, in Deokcheon, Pyeongan Province, then part of the Joseon Dynasty. He spent parts of his childhood in Jinju and Miryang, both located in Gyeongsang Province. From a young age, after returning to his hometown of Deokcheon, he dedicated himself to the study of Korean medicine. He also pursued studies in Neo-Confucianism, laying a foundation for his later educational activities.

2.2. Medical and Commercial Activities

In 1884, Kang Woo-kyu relocated to Hongwon, a town in Hamgyong Province. There, he established himself as a respected Korean medicine doctor, providing medical care to the local community. Concurrently, he engaged in educational endeavors, teaching children Neo-Confucianism and classical Chinese texts. It is believed that he moved to Hongwon partly as a refuge, as his personal safety was reportedly jeopardized due to his involvement in various Korean patriotic movements. Upon his arrival in Hongwon, Kang was known to have brought a substantial sum of money, which he utilized to engage in commercial ventures. He operated a general merchandise store with his son, Jung Geon, on Nammun Street, a central thoroughfare in Hongwon. The store's inventory primarily included items such as paint, tobacco pipes, cotton thread, and fabric. In addition to his retail business, Kang also provided financial assistance to traders, lending them money at low interest rates, which further solidified his standing in the local economy.

2.3. Exile and Preparations for Independence Activities

Kang Woo-kyu was profoundly angered by the escalating Japanese encroachment on Korean sovereignty, particularly the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905, which effectively made Korea a protectorate, and the subsequent Japan-Korea Treaty of 1910, which led to Japan's full annexation and colonial rule over Korea. At this time, he was a middle-aged man over 50 years old. In the autumn of 1910, driven by a strong desire to restore national sovereignty, Kang made the resolute decision to go into exile. He first arranged for his eldest son, Jung Geon, along with his family, to relocate to Khabarovsk, Russia. The following spring, in 1911, Kang himself departed from Hongwon and sought asylum in Dudogu, located in the northern part of Jiandao (also known as Gando) in Manchuria. During his initial period of exile there, he continued to operate a herbal medicine shop.

3. Independence Activities in Exile

While in exile, Kang Woo-kyu actively organized and contributed to the Korean independence movement, establishing communities and educational institutions that served as vital bases for resistance.

3.1. Activities in Manchuria

In 1915, Kang Woo-kyu moved from Dudogu to Yo-dong in Raohe County, Jilin Province, a region in Northeast China. From this new base, he frequently traveled to and from Vladivostok, Russia, to coordinate and advance independence efforts. He undertook the arduous task of reclaiming farmland around the Yoha River, where he meticulously constructed a Korean village named Shinheungchon (신흥촌ShinheungchonKorean). This village, built through Kang's dedicated efforts, subsequently became a crucial stronghold and primary base for Korean independence forces operating across Siberia and North Manchuria. In 1917, demonstrating his commitment to national education as a means of fostering independence, Kang founded Gwandong Middle School in Tonghua County, Jilin Province. As a devout Presbyterian Christian, he utilized his position within the church school to instill anti-Japanese sentiment among the students and the wider Korean community residing in the area. He openly condemned Japanese war crimes in his teachings and frequently gathered villagers in the school auditorium to promote national consciousness and rally support for the independence cause.

3.2. Collaboration in Vladivostok

Following the outbreak of the March 1st Movement in 1919, Kang Woo-kyu intensified his organizational efforts. He gathered students and fellow Koreans at Gwandong School, focusing on the Yeohyeon region to mobilize and expand the independence movement. Believing that a simple, non-violent independence movement alone would not achieve the liberation of his homeland, he traveled to Vladivostok. There, he engaged with prominent independence activists, including Lee Dong-hwi, and became actively involved in the Senior Citizen's Association (also known as the Old People's Association, 노인동맹단Noin DongmaengdanKorean). He served as the chief of the Yo Ha-yeon branch of this organization, working alongside figures such as Lee Seung-kyo, who was Lee Dong-hwi's father. During his time in Vladivostok in 1914, he also engaged in significant exchanges with the esteemed patriot Kye Bong-woo. It was during this period of collaboration and strategic planning in Vladivostok that Kang Woo-kyu, as the Jilin Province branch chief of the Senior Citizen's Association, resolved to assassinate the Japanese Governor-General.

4. Infiltration and Assassination Attempt

Kang Woo-kyu's determination led him to undertake a perilous infiltration back into Japanese-occupied Korea, culminating in his audacious attempt to assassinate the Governor-General, an event that shocked the colonial authorities.

4.1. Infiltration into Korea

In 1919, after making arrangements to transfer the management of Gwandong Middle School and Shinheungchon village to other Korean expatriates, Kang Woo-kyu clandestinely returned to Japanese-occupied Korea. His mission was to carry out a direct action against the colonial regime. He acquired a grenade from a Russian contact as his weapon. Accompanied by Huh Hyung, he infiltrated the Korean peninsula via Wonsan and then proceeded towards Keijō (京城府Keijō-fuJapanese, the colonial name for Seoul). Japanese police at the time conducted baggage inspections for incoming individuals, but notably exempted elderly people over the age of 60, a loophole that Kang, then 64, exploited. To evade detection, he ingeniously concealed the grenade by wearing it between his legs, hidden within a diaper.

4.2. The Assassination Attempt

On September 2, 1919, amidst growing internal and external political tensions, Saitō Makoto, a Japanese admiral, was appointed as the new Governor-General of Korea, succeeding Hasegawa Yoshimichi. On the very day of Saitō's arrival in Korea, Kang Woo-kyu executed his plan. At Namdaemun Station (now Seoul Station), as Saitō's carriage arrived, Kang threw the bomb at the new Governor-General. The explosion, while powerful, unfortunately missed Saitō Makoto. However, the blast caused significant casualties among the crowd gathered to welcome the Governor-General, including Japanese police escorts, journalists, and other civilians. Reports indicate that at least 37 people sustained moderate to severe injuries. Among the injured was an American, a relative of Carter Harrison Sr., a former Mayor of Chicago who had been assassinated in 1893. The *El Paso Herald* specifically reported that twenty individuals were injured in the incident. Dr. Oliver Avison, who was present at the scene, later conveyed to Yoon Chi-ho that while the Governor-General's party was unharmed, several onlookers were injured by the explosion. The Japanese press at the time, and later historical accounts from Japan, characterized this incident as an act of "terrorism" due to the civilian casualties.

5. Arrest, Trial, and Execution

The aftermath of the bombing led to Kang Woo-kyu's swift apprehension, a judicial process under colonial rule, and ultimately, his execution, during which he maintained his defiant stance.

5.1. Arrest and Trial

Following the failed assassination attempt, Kang Woo-kyu managed to escape the immediate scene and went into hiding. He sought refuge in the homes of Jang Ik-kyu and Lim Seung-hwa, having been introduced to them by Oh Tae-yeong. However, his evasion was short-lived. He was eventually apprehended by Kim Tae-seok, a detective from the Higher Affairs section of the Joseon Governor-General's Office, known for his role in suppressing independence movements and his pro-Japanese leanings. Kang Woo-kyu was arrested and subsequently incarcerated on September 17, 1919. In connection with the bombing, five other individuals were also arrested. Kang was brought before the Higher Court of the Governor-General's Office, where he faced charges of attempted murder and causing civilian casualties. Despite the gravity of the charges and the pressure of the colonial judicial system, Kang maintained a resolute and dignified demeanor throughout his trial, refusing to compromise his convictions. He was ultimately sentenced to death.

5.2. Execution and Last Words

Kang Woo-kyu's death sentence was confirmed, and he awaited his final day with remarkable composure. While imprisoned at Seodaemun Prison in Gyeongseong (Seoul), he reportedly read the Bible daily and engaged in morning and evening prayers, displaying a relaxed and unyielding spirit. On November 29, 1920, Kang Woo-kyu was executed by hanging at Seodaemun Prison. Until his last breath, he never renounced his beliefs and remained defiant in the face of the colonial authorities. Before his execution, he conveyed a powerful message to his sons, urging them not to mourn his death but rather to feel ashamed that he had done so little for his country. He emphasized that the education of young people was his paramount concern, even in his final moments, expressing a wish that his death might provide "a little impetus to the minds of the young people." He informally instructed his sons to disseminate his will to schools and churches across the nation. In response to the bombing incident, the Japanese colonial authorities significantly increased their police presence in Korea, expanding the force from 12,000 to 20,000 members.

6. Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Kang Woo-kyu's actions and ultimate sacrifice left an indelible mark on the Korean independence movement, earning him posthumous recognition and a complex historical evaluation that acknowledges both his courage and the controversial nature of his methods.

6.1. Posthumous Recognition and Memorials

Kang Woo-kyu's remains were initially interred at a public cemetery in Sinsa-dong, Eunpyeong-gu, Seoul. In 1954, his remains were relocated to Suyu-ri in Gangbuk-gu, and then in 1967, they were finally moved to the Patriots' Section of the Seoul National Cemetery, where many distinguished independence activists are laid to rest. In March 1962, the government of the Republic of Korea posthumously honored Kang Woo-kyu with the Order of Merit for National Foundation, initially as a Grand Marshal (later revised to the Republic of Korea Chapter), recognizing his profound contributions to the nation's independence. A Chinese poem, written by Kang in his will just before his execution at Seodaemun Prison, has been preserved and is inscribed on an epigraph at the Independence Hall of Korea. The poem reads:

"I am on the guillotine, as if I were amidst the spring breeze.

I have a body but no country; how can I not have feelings?"

A prominent statue of Kang Woo-kyu stands in front of Seoul Station Plaza, commemorating his historic assassination attempt at that very location. The statue, measuring 16 ft (4.9 m) in height, was erected on September 2, 2011, funded by a combination of public donations and government support totaling 820.00 M KRW.

6.2. Historical Assessment and Criticism

Kang Woo-kyu's actions have been subject to various historical interpretations. From the perspective of the Korean independence movement, his act is hailed as the first significant violent resistance following the widespread March 1st Movement. It served as a powerful warning to the newly appointed Governor-General Saitō Makoto and played a crucial role in elevating national consciousness among Koreans both at home and abroad. His steadfastness during his trial, imprisonment, and execution deeply moved and inspired Koreans who were actively involved in or sympathetic to the independence cause, transforming the judicial process itself into a continuation of the independence struggle.

However, contemporary figures and some historical accounts have offered critical perspectives. For instance, Yoon Chi-ho, a prominent intellectual of the time, expressed dismay upon hearing of the bombing, remarking that it was "truly painful" and questioning if Koreans had forgotten that the assassination of Itō Hirobumi had paradoxically accelerated the Japan-Korea annexation. He viewed such acts of "terrorism" as counterproductive. Similarly, some Japanese sources, particularly those from the time of the incident, explicitly labeled Kang Woo-kyu as a "terrorist" due to the civilian casualties caused by the explosion. Conversely, Chiba, the Chief of Police in Gyeonggi Province at the time, reportedly expressed a nuanced view, stating, "I don't feel bad about it. If you change your stance, Kang Woo-kyu was predominant [a patriot]." This statement reflects a recognition of his patriotic motivations, even from an opposing official.

6.3. Impact on the Independence Movement

Kang Woo-kyu's audacious act and his unwavering spirit solidified his role as a powerful symbol of resistance against Japanese colonial rule. His willingness to sacrifice his life for national liberation deeply resonated with the Korean populace, contributing significantly to the awakening and strengthening of national consciousness. His legacy continued to inspire future generations of independence fighters, demonstrating that even in the face of overwhelming odds, defiance and a commitment to freedom could ignite hope and further the cause of independence. His actions underscored the diverse strategies employed by Korean patriots, ranging from non-violent protests to direct armed resistance, all aimed at achieving national sovereignty.