1. Overview

Judith Quiney, born Judith Shakespeare, was the younger daughter of the renowned playwright William Shakespeare and his wife, Anne Hathaway. Baptized on 2 February 1585, she was the fraternal twin of her only brother, Hamnet Shakespeare. Her life was significantly shaped by her marriage to Thomas Quiney, a vintner from Stratford-upon-Avon. The circumstances surrounding their marriage, particularly Quiney's pre-marital misconduct, are believed to have influenced her father's decision to revise his will, adding specific provisions to safeguard Judith's inheritance from her husband's potential mismanagement. While the bulk of Shakespeare's estate was meticulously entailed to his elder daughter, Susanna, and her male heirs, Judith's portion was carefully protected. Judith and Thomas Quiney had three children, all of whom she tragically outlived. Her life, often viewed through the lens of her famous father, offers insights into the social constraints and legal realities faced by women in the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. She has been depicted in various fictional works, serving as a character through whom unknown aspects of her father's life and the broader experiences of women in that period are explored.

2. Birth and Early Life

Judith Quiney's early life was rooted in Stratford-upon-Avon, as the daughter of one of England's most celebrated literary figures. Her birth and family connections provided the initial context for her upbringing, while evidence regarding her literacy offers a glimpse into her educational opportunities.

2.1. Birth and Family

Judith Shakespeare was born to William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway. She was the younger sister of Susanna and the fraternal twin of Hamnet Shakespeare. Both Judith and Hamnet were baptized on 2 February 1585, a record that appears in the parish register for Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon as "Hamnet & Judeth sonne & daughter to William Shakspere," recorded by the vicar, Richard Barton of Coventry. The twins were named after Hamnet and Judith Sadler, close friends of their parents; Hamnet Sadler was a baker in Stratford. Tragically, Hamnet died at the young age of eleven.

2.2. Literacy

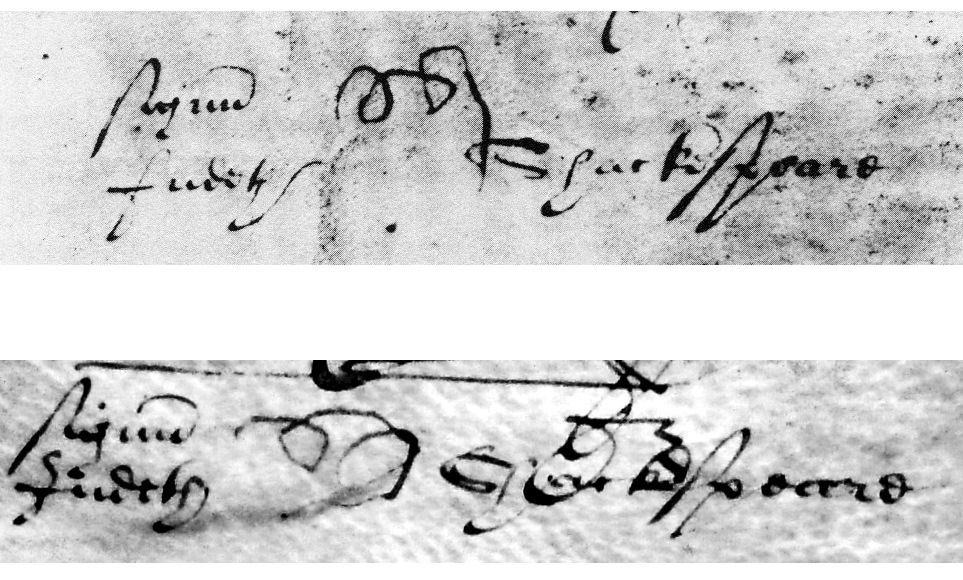

Unlike her father and her husband, Judith Shakespeare was likely illiterate. Evidence for this comes from a deed of sale in 1611, where she witnessed the sale of a house for 131 GBP to William Mountford, a wheelwright, from Elizabeth Quiney (who would later become Judith's mother-in-law) and Elizabeth's eldest son, Adrian. On this document, Judith signed twice using a distinct "pigtail" mark, which was a cursive "J" facing downwards, rather than her full name. This practice suggests she did not possess the ability to write her signature, indicating limited formal education.

3. Marriage to Thomas Quiney

Judith Shakespeare's marriage to Thomas Quiney was marked by unusual circumstances and immediate challenges, including legal repercussions that underscored the societal norms and religious strictures of the time.

3.1. Background and Circumstances of Marriage

On 10 February 1616, Judith Shakespeare married Thomas Quiney, a vintner from Stratford, at Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. The ceremony was likely officiated by the assistant vicar, Richard Watts, who later married Quiney's sister Mary. The marriage took place during the pre-Lenten season of Shrovetide, a period when marriages were generally prohibited without a special dispensation from the church. In 1616, this ban, which included Ash Wednesday and Lent, began on 23 January, known as Septuagesima Sunday, and lasted until 7 April, the Sunday after Easter. Judith and Thomas had failed to obtain the necessary special license from the Bishop of Worcester. While they had presumably posted the required banns in church, this was not deemed sufficient. The infraction was considered minor, possibly due to the minister's oversight, as three other couples were also wed that February. Nevertheless, Quiney was summoned by Walter Nixon to appear before the consistory court in Worcester. Walter Nixon himself was later implicated in a Star Chamber case and convicted of forging signatures and accepting bribes. Quiney failed to appear by the designated date of 12 March 1616, resulting in a judgment of excommunication recorded in the register. It remains unknown whether Judith was also excommunicated, but the punishment was short-lived, as they were present in church for their first child's baptism in November of the same year.

3.2. Thomas Quiney's Misconduct and its Impact

The marriage began under difficult circumstances, as Thomas Quiney had recently impregnated another woman, Margaret Wheeler. Margaret and her child died during childbirth and were buried on 15 March 1616. Just days later, on 26 March, Quiney was compelled to appear before the Bawdy Court, which handled cases of "whoredom and uncleanliness." In open court, he confessed to "carnal copulation" with Margaret Wheeler and submitted himself for correction. He was sentenced to perform open penance "in a white sheet (according to custom)" before the congregation on three consecutive Sundays. Additionally, he was required to confess his crime, this time in ordinary clothes, before the Minister of Bishopton in Warwickshire. However, the first part of his sentence was remitted, effectively replacing it with a fine of 0.25 GBP to be donated to the parish's poor. As Bishopton possessed only a chapel and no full church, Quiney was spared the full public humiliation of the penance.

4. William Shakespeare's Will and Inheritance Distribution

The challenging start to Judith's marriage, despite her husband's family being otherwise unremarkable, is widely believed to be the primary reason for William Shakespeare's swift alterations to his last will and testament. The revisions specifically addressed Judith's inheritance, implementing safeguards against Thomas Quiney's potential financial mismanagement.

4.1. Revision of the Will

William Shakespeare first summoned his lawyer, Francis Collins, in January 1616. On 25 March of the same year, he made further significant alterations to his will. These changes were likely prompted by his declining health and, more critically, by his profound concerns regarding Thomas Quiney's character and financial reliability, particularly in light of the recent scandal surrounding his marriage to Judith. The initial draft of the will had included a provision for "vnto my sonne in L[aw]"; however, this phrase was subsequently struck out and replaced with Judith's name, indicating a direct shift in the bequest's recipient and a clear intent to separate her inheritance from her husband's control.

4.2. Inheritance Provisions and Restrictions

Shakespeare's will included specific financial bequests and property stipulations designed to protect Judith's inheritance. She was bequeathed 100 GBP "in discharge of her marriage porcion." An additional 50 GBP was promised to her if she chose to relinquish the cottage on Chapel Lane, which she owned. Furthermore, if Judith or any of her children were still alive three years after the date of the will, she was to receive a further 150 GBP. Crucially, she was only entitled to the interest from this sum, with the principal explicitly denied to Thomas Quiney, unless he could bestow lands of equal value upon Judith. In a separate, more personal bequest, Judith was also given "my broad silver gilt bole."

The bulk of Shakespeare's estate, which included his main residence, New Place, his two houses on Henley Street, and various lands in and around Stratford, was structured through an elaborate entail. This legal arrangement dictated the succession of the estate in a specific, descending order:

# His elder daughter, Susanna Hall.

# Upon Susanna's death, "to the first sonne of her bodie lawfullie yssueing & to the heires Males of the bodie of the saied first Sonne lawfullie yssueing."

# To Susanna's second son and his male heirs.

# To Susanna's third son and his male heirs.

# To Susanna's "ffourth ... ffyfth sixte & Seaventh sonnes" and their male heirs.

# To Elizabeth Hall, Susanna and John Hall's firstborn daughter, and her male heirs.

# To Judith and her male heirs.

# To whatever heirs the law would normally recognize.

This complex entailment is generally interpreted as a strong indication that William Shakespeare did not trust Thomas Quiney with the management of his inheritance. While some scholars have speculated that it might simply reflect a preference for Susanna, the detailed provisions concerning Judith's portion and the explicit exclusion of Thomas from direct control over the principal strongly suggest Shakespeare's intent to safeguard his daughter's financial future from her husband's influence.

5. Children

Judith and Thomas Quiney had three children, whose early deaths had significant ramifications for the family's inheritance and the continuation of William Shakespeare's direct lineage.

5.1. Birth and Death of Children

Judith and Thomas Quiney had three sons:

- Shakespeare Quiney** (baptized 23 November 1616 - buried 8 May 1617): Named after his grandfather, he died at only six months of age.

- Richard Quiney** (baptized 9 February 1618 - buried 6 February 1639): Richard's name was common within the Quiney family, shared by both his paternal grandfather and an uncle. He died at the age of 21.

- Thomas Quiney** (baptized 23 January 1620 - buried 28 January 1639): He died at the age of 19.

Richard and Thomas Quiney were buried within one month of each other, a profound tragedy for Judith. The exact cause of death for her two younger sons is not definitively known. Judith Quiney ultimately outlived all three of her children by many years, a testament to her longevity but also a source of immense personal loss.

5.2. Inheritance and Legal Consequences

The deaths of all of Judith's children had significant legal ramifications for the inheritance of William Shakespeare's estate. The elaborate entail established in Shakespeare's will meant that with the passing of Judith's male heirs, the succession of the estate would further fall upon Susanna's line. Consequently, Susanna, along with her daughter Elizabeth and son-in-law, was compelled to establish a new settlement using a complex legal device to manage the inheritance for her own branch of the family. This legal maneuvering and wrangling over the estate continued for an additional thirteen years, finally concluding in 1652. The absence of surviving male heirs from both Susanna and Judith's lines meant that Shakespeare's direct lineage through his children ultimately ended.

6. Residences

Judith Quiney and her husband, Thomas, were associated with several properties in Stratford-upon-Avon, reflecting their familial ties and financial arrangements within the town.

6.1. Chapel Lane and The Cage

The exact residence of the Quineys immediately following their marriage remains unknown. Judith inherited her father's cottage on Chapel Lane in Stratford. Concurrently, Thomas had held the lease on a tavern named "Atwood's" on High Street since 1611. However, the Chapel Lane cottage later passed from Judith to her elder sister, Susanna, as part of the settlement outlined in their father's will. In July 1616, Thomas Quiney exchanged properties with his brother-in-law, William Chandler, relocating his vintner's shop to the upper half of a house situated at the corner of High Street and Bridge Street. This particular house became famously known as "The Cage" and is the residence traditionally linked with Judith Quiney. In the 20th century, The Cage underwent several transformations, serving for a period as a Wimpy Bar before being converted into the Stratford Information Office.

The history of The Cage further illuminates William Shakespeare's distrust of Judith's husband. Around 1630, Thomas Quiney attempted to sell the lease on the house, but his kinsmen intervened and prevented the sale. To safeguard the interests of Judith and her children, the lease was formally signed over in 1633 to a trust. This trust included John Hall, Susanna's husband; Thomas Nash, the husband of Judith's niece; and Richard Watts, the vicar of nearby Harbury, who was also Quiney's brother-in-law and had officiated at Thomas and Judith's wedding. Ultimately, in November 1652, the lease to The Cage came into the possession of Thomas's eldest brother, Richard Quiney, a grocer residing in London.

7. Death

Judith Quiney's death was recorded on 9 February 1662, approximately one week after her 77th birthday. She demonstrated remarkable longevity for her era, outliving her last surviving child by 23 years. She was interred within the grounds of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, the same church where she was baptized and married. However, the precise location of her grave within the churchyard is not known. Records concerning her husband, Thomas Quiney, are less complete for his later years. It has been speculated that he may have died in either 1662 or 1663, a period for which parish burial records are incomplete, or that he may have left Stratford-upon-Avon altogether. By this time, his nephew in London was known to be holding the lease to The Cage.

8. Portrayal in Literary Works

Judith Quiney, as the daughter of William Shakespeare, has captured the imagination of various authors and artists, leading to her depiction in numerous literary and creative works. These portrayals often explore her relationship with her father, her personal struggles, and the broader societal constraints faced by women during her time.

8.1. Appearance in Novels and Plays

Judith Quiney has been a recurring character in fictional interpretations of Shakespeare's life and era. She is notably portrayed in William Black's novel, Judith Shakespeare: Her Love Affairs and Other Adventures, which was serialized in Harper's Magazine in 1884. She also appears as one of the main characters in Edward Bond's 1973 play, Bingo, which focuses on the final years of her father's life in retirement in Stratford-upon-Avon. In Neil Gaiman's graphic novel series, The Sandman, Judith is featured in one of the concluding stories, with Gaiman drawing parallels between her and the character Miranda from Shakespeare's play The Tempest.

Grace Tiffany's 2003 novel, My Father Had a Daughter: Judith Shakespeare's Tale, centers on Judith's story. A radio play titled Judith Shakespeare by Nan Woodhouse depicts her as a solitary figure, longing to be a part of her playwright father's world. In this portrayal, she travels to London to join him and becomes involved in a troubling affair with a young aristocrat. The short story "Shakespeare's Daughter" by Mary Burke was short-listed for a 2007 Hennessy/Sunday Tribune Irish Writer prize. More recently, Maggie O'Farrell's 2020 novel, Hamnet, delves into Judith's childhood and the profound impact of her twin brother's death. In Kenneth Branagh's 2018 Sony Pictures film All Is True, Kathryn Wilder portrays Judith as a rebellious and angry young woman who harbors resentment towards her father's enduring love for her deceased twin.

8.2. Virginia Woolf's Judith Shakespeare

One of the most significant literary interpretations of a character named Judith Shakespeare comes from Virginia Woolf's influential 1929 essay, A Room of One's Own. However, it is crucial to note that Woolf's "Judith Shakespeare" is presented as William Shakespeare's *sister*, not his historical daughter. In reality, Shakespeare's sister was named Joan. Beyond the similar names and the historical setting, there is no direct connection between the historical Judith Quiney and Woolf's fictional creation.

Woolf's character serves as a powerful literary device to explore the societal limitations faced by women in the Elizabethan era, particularly those with creative potential. In Woolf's narrative, Judith Shakespeare is depicted as possessing talent equal to her brother's but is denied the educational opportunities afforded to him. When her father attempts to marry her off, she flees to join a theatre company, only to be rejected due to her gender. She subsequently becomes pregnant, is abandoned by her partner, and ultimately commits suicide. Woolf created this character to highlight a historical gap and to make a poignant point about the immense struggles a female poet or playwright would have encountered during that period. Woolf pondered why so few talented women from that time were known, observing, "What I find deplorable... is that nothing is known about women before the eighteenth century." Through her fictional Judith, Woolf underscored the profound impact of societal structures on women's creative expression and historical visibility.

9. Historical Evaluation and Legacy

Judith Quiney's place in history is primarily defined by her direct familial connection to William Shakespeare, yet her life also offers a unique lens through which to understand the experiences of women in 17th-century England. Despite being the daughter of a literary giant, her personal narrative is largely shaped by the legal and social constraints of her time, particularly those concerning marriage, property, and inheritance.

Her marriage to Thomas Quiney, fraught with scandal and financial instability, directly influenced Shakespeare's will, leading to provisions designed to protect Judith's assets. This aspect of her life highlights the vulnerability of women's economic security when tied to a husband's conduct and the legal mechanisms employed to mitigate such risks. The tragic early deaths of all her children further complicated the line of succession for Shakespeare's estate, underscoring the precariousness of life and lineage in that era.

In contemporary cultural interpretations, Judith Quiney has become a symbolic figure. Her story, though sparsely documented, has inspired numerous literary works that attempt to flesh out her character and explore themes of gender, talent, and societal limitations. Virginia Woolf's fictional "Judith Shakespeare," while not historically accurate as Shakespeare's daughter, powerfully articulates the challenges faced by women with creative aspirations in a patriarchal society. This fictional portrayal has significantly contributed to Judith Quiney's legacy, transforming her from a relatively obscure historical figure into a symbol for the unfulfilled potential and silenced voices of women in history. Through these artistic interpretations, Judith Quiney continues to prompt reflection on the historical experiences of women and the enduring impact of societal structures on individual lives.