1. Biography

John Wilkinson's life spanned a period of immense industrial change, in which he was a central figure, transforming the iron industry through his inventions and expansive business ventures.

1.1. Early Life and Education

John Wilkinson was born in 1728 in Little Clifton, Bridgefoot, Cumberland (now part of Cumbria), as the eldest son of Isaac Wilkinson and Mary Johnson. His father, Isaac Wilkinson, was a potfounder at the local blast furnace and was one of the first in England to use coke instead of charcoal for iron production, a technique pioneered by Abraham Darby I. John and his half-brother, William, who was 17 years younger, were raised in a Nonconformist Presbyterian family. John received his education at a dissenting academy in Kendal, Westmorland (also now part of Cumbria), which was run by Dr. Caleb Rotherham. His sister, Mary, later married Joseph Priestley, a prominent non-conformist and scientist, in 1762. Priestley also contributed to the education of John's younger brother, William.

1.2. Early Career

In 1745, at the age of 17, John Wilkinson began a five-year apprenticeship with a merchant in Liverpool. Following this period, he entered into a business partnership with his father. When his father relocated to the Bersham furnace near Wrexham, North Wales, in 1753, John chose to remain in Kirkby Lonsdale in Westmorland. He married Ann Maudesley on 12 June 1755.

1.3. Expansion of Iron Business

After gaining experience working with his father in the foundry, John Wilkinson became a partner in the Bersham concern from 1755. In 1757, in collaboration with other partners, he established a new blast furnace at Willey, near Broseley in Shropshire. He later built another furnace and works at New Willey, eventually making his home in Broseley in a house named 'The Lawns', which served as his primary headquarters for many years. Adjacent to 'The Lawns' were other properties used for administration, including one called 'The Mint,' which facilitated the distribution of thousands of trade tokens.

Wilkinson's industrial empire expanded significantly within East Shropshire, where he developed iron works at Snedshill, Hollinswood, Hadley, and Hampton Loade. He and his partner Edward Blakeway also leased land to construct another major works at Bradley in Bilston parish, near Wolverhampton. Bradley became his largest and most successful enterprise, and it was here that he conducted extensive experiments aimed at substituting raw coal for coke in cast iron production. At its peak, the Bradley complex was a comprehensive industrial hub, encompassing multiple blast furnaces, a brick works, potteries, glass works, and rolling mills. The proximity of the Birmingham Canal to the Bradley works further enhanced its operational efficiency by providing crucial transport links. Wilkinson's pioneering efforts and extensive operations in the region led to him being recognized as the 'Father' of the extensive South Staffordshire iron industry, with Bilston marking the inception of what would become known as the Black Country. In 1761, he also took over the management of Bersham Ironworks.

2. Major Inventions and Technological Innovations

John Wilkinson was a prolific inventor whose innovations were instrumental in advancing industrial processes, particularly in the iron industry.

2.1. Cannon Boring Machine

The Bersham works under Wilkinson's management became renowned for its high-quality casting, especially as a significant producer of guns and cannon. Historically, cannons were cast with a core and then bored to refine their internal surface and remove imperfections. However, this method often resulted in inaccuracies and a higher risk of the cannon exploding during use. In 1774, Wilkinson patented a revolutionary technique for boring iron guns from a solid piece of metal. This method involved rotating the gun barrel itself rather than the boring-bar, ensuring a more uniform and accurate bore. This precision greatly enhanced the accuracy of the cannons and significantly reduced the likelihood of catastrophic failures. While bronze cannons were already being bored from solid castings, Wilkinson's innovation was particularly novel for large iron naval cannons. Although his patent was quashed in 1779, primarily because the Royal Navy viewed it as an undesirable monopoly, Wilkinson maintained his position as a leading manufacturer of cannons due to the superior quality and safety of his products. In 1792, Wilkinson acquired the Brymbo Hall estate in Denbighshire, not far from Bersham, where he installed additional furnaces and plant. After his death and the subsequent decline of his industrial empire, the ironworks remained dormant for several years until 1842, when it was revived and eventually became Brymbo Steelworks, which continued operations until 1990.

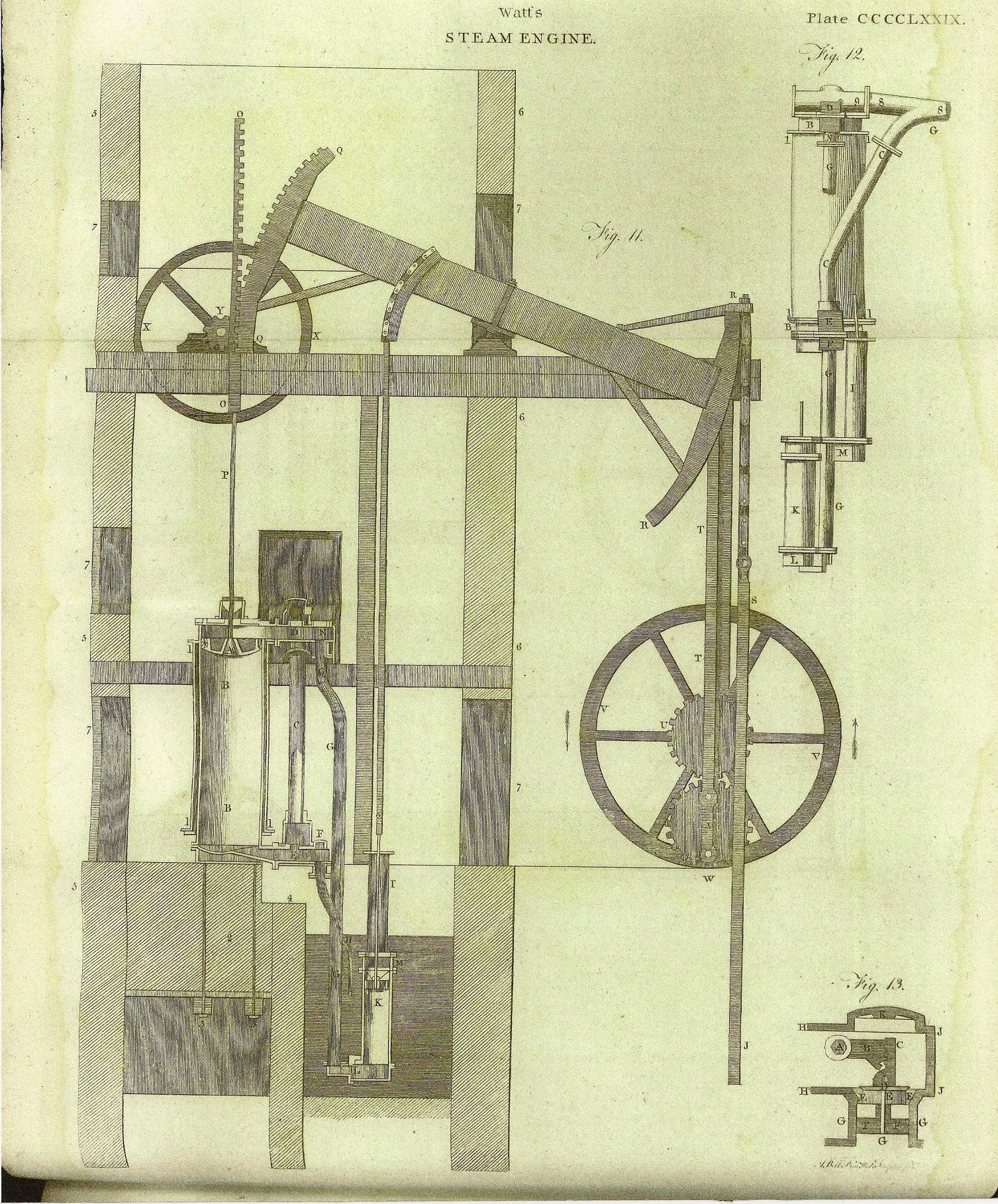

2.2. Steam Engine Cylinder Boring Machine

One of Wilkinson's most critical innovations addressed a significant challenge faced by James Watt in his development of the steam engine. For several years, Watt had struggled to obtain accurately bored cylinders for his steam engines; he was often forced to use hammered iron, which was irregularly shaped, leading to considerable steam leakage past the piston and inefficient operation. In 1774, John Wilkinson invented a groundbreaking boring machine that solved this problem. Unlike the cantilevered borers then in use, Wilkinson's machine featured a shaft that held the cutting tool, which extended through the entire cylinder and was supported on both ends. This double-ended support system prevented the shaft from flexing or tilting under cutting resistance, allowing for unprecedented precision.

With this machine, Wilkinson was able to bore the first accurately machined cylinder for Boulton & Watt's inaugural commercial steam engine. His precision was so vital that he secured an exclusive contract for the provision of cylinders to Boulton & Watt, largely due to the minimal tolerance achieved between the piston and cylinder, which dramatically improved efficiency by reducing steam losses. This achievement marked a significant milestone in the evolution of boring technology, broadening its application beyond gun barrels to encompass engines, pumps, and a wide array of other industrial uses. While the primary market for steam engines had initially been for pumping water out of mines, Wilkinson foresaw their much broader utility in driving machinery within ironworks, such as blowing engines, forge hammers, and rolling mills. The first rotary action steam engine was installed at his Bradley works in 1783, signifying this expanded vision. Among his many inventions was also a reversing rolling mill equipped with two steam cylinders, which substantially improved the economic efficiency of the rolling process. Wilkinson also actively sought orders for these more efficient steam engines and other cast iron applications from the owners of Cornish copper mines, even purchasing shares in eight of these mines to help provide necessary capital.

2.3. Hydraulic Blowing Engine and Other Innovations

Wilkinson's inventive prowess extended beyond boring machines. In 1757, he patented a hydraulically powered blowing engine designed to enhance the air blast through the tuyeres for blast furnaces. This innovation significantly improved the rate of cast iron production by allowing for higher temperatures and more efficient combustion. The historian Joseph Needham noted the conceptual similarity between Wilkinson's design and an earlier hydraulic blowing engine described by the Chinese Imperial Government metallurgist Wang Zhen in his 1313 Treatise on Agriculture.

In addition to his contributions to furnace efficiency, Wilkinson was a pioneer in the use of new materials for transport. In 1787, he launched the first barge made entirely of wrought iron, constructed in Broseley. This marked a significant development that would become commonplace for canal barges in the coming decades and, later, for large ships in the following century. He also patented several other inventions that further advanced the iron industry and its applications.

3. Key Business Activities and Investments

John Wilkinson was not only an inventor but also a shrewd businessman and investor, engaging in a wide range of activities that supported and expanded his industrial empire.

3.1. Contribution to the Iron Bridge Construction

In 1775, John Wilkinson was the primary driving force behind the initiation of the Iron Bridge project. This ambitious undertaking aimed to connect the then-important industrial town of Broseley with the opposite bank of the River Severn, facilitating the transport of raw materials and finished goods. Wilkinson's friend, the architect Thomas Farnolls Pritchard, had proposed the plans for the bridge to him. A committee of subscribers, predominantly Broseley businessmen, was formed to advocate for the use of iron instead of traditional wood or stone, to secure price quotations, and to obtain an authorizing Act of Parliament.

Wilkinson's exceptional powers of persuasion and unwavering determination were crucial in maintaining the group's support throughout several challenges encountered during the parliamentary process. Had Wilkinson not succeeded in galvanizing this support and drawing backing from influential parliamentarians, the iconic bridge might never have been built, or might have been constructed from less innovative materials. Consequently, the district might not have been named 'Ironbridge', nor would the area have achieved its status as a World Heritage Site. Although Abraham Darby III was ultimately selected as the preferred builder, quoting 3.15 K GBP for the construction, and Wilkinson sold his shares to Darby III in 1777, his initial impetus and continued influence were indispensable in bringing the project to its successful completion in 1779 and its official opening in 1781.

3.2. Ventures into Copper and Lead Industries

After accumulating considerable wealth from selling high-quality iron goods and reaching the practical limits of investment expansion within the iron sector, John Wilkinson diversified his interests into the copper and lead industries. His metallurgical expertise proved invaluable in these new ventures. A significant opportunity arose when the Royal Navy began to copper-clad the hulls of its frigates in 1761, starting with the frigate HMS Alarm. This practice was adopted to prevent the growth of marine biofouling and protect against the destructive Teredo shipworm, issues that severely reduced ship speed and caused hull damage, particularly in tropical waters. The success of this initiative led the Navy to decree that all its ships should be copper-clad, creating an enormous demand for copper that Wilkinson observed during his visits to shipyards.

He invested in numerous copper interests, including purchasing shares in eight Cornish copper mines. During this period, he forged a strong partnership with Thomas Williams, known as the 'Copper King' of the Parys Mountain mines in Anglesey. Wilkinson not only supplied Williams with substantial quantities of iron plates and equipment but also provided scrap iron essential for the process of recovering copper from solutions through cementation. Wilkinson acquired a 1/16th share in the Mona Mine at Parys Mountain and also invested in Williams's industrial operations in Holywell, Flintshire, St Helens near Liverpool, and Swansea, South Wales. Wilkinson and Williams collaborated on several projects, including being among the first to issue trade tokens (known as 'Willys' and 'Druids') to alleviate the prevailing shortage of small coins. In 1785, they jointly established the Cornish Metal Company, a marketing firm for copper, with the goal of ensuring fair returns for Cornish miners and stable prices for copper users. This company set up warehouses in key commercial centers such as Birmingham, London, Bristol, and Liverpool.

Wilkinson also diversified into the lead industry. He purchased lead mines at Minera in Wrexham, five miles from Bersham, and at Llyn Pandy in Soughton (now Sychdyn) and Mold, both in Flintshire. To make these mines viable again, he installed modern steam pumping engines. The lead produced from these mines was exported through the port of Chester. To utilize some of the lead, Wilkinson established a lead pipe works in Rotherhithe, London. This factory operated for many years, eventually producing the solder filler alloys used in the car factory at Dagenham.

3.3. Coinage and Financial Activities

John Wilkinson's extensive business interests required robust financial management, particularly during a period when official coinage was often in short supply. To address the scarcity of small denomination coins, he took an active role in issuing trade tokens. These tokens, including the distinctive 'Willys' and 'Druids' tokens, served as a form of private currency, facilitating daily transactions for his vast workforce and trading partners. To further support his widespread business operations and ensure the smooth circulation and acceptance of his trade tokens, Wilkinson strategically invested in and formed partnerships with various banks located in key industrial and commercial hubs such as Birmingham, Bilston, Bradley, Brymbo, and Shrewsbury. These financial alliances provided him with the necessary capital and banking services to manage his complex and rapidly expanding industrial empire.

4. Philanthropy and Social Contributions

Beyond his role as an industrial innovator, John Wilkinson earned a commendable reputation as an employer who prioritized the welfare of his workforce and contributed to his community. Wherever new works were established, Wilkinson ensured that cottages were built to provide adequate housing for his employees and their families, a progressive measure for the era.

He also provided significant financial support to his brother-in-law, the renowned chemist Dr. Joseph Priestley, aiding his scientific research. Wilkinson actively participated in civic life; he served as a church warden in Broseley and was later elected High Sheriff of Denbighshire for 1799. Demonstrating his practical approach to education, he supplied iron troughs to schools lacking slates, which could be filled with sand for students to practice writing and arithmetic. Furthermore, he donated a cast-iron pulpit to the church in Bilston, reflecting both his generosity and his enduring fascination with iron.

5. Later Life and Death

In his later years, John Wilkinson remained a prominent figure in the industrial landscape, known for both his vast wealth and his increasingly eccentric personality.

5.1. Personal Life and Eccentricities

John Wilkinson married Ann Maudsley in 1759. Her family's wealth, particularly her dowry, was instrumental in funding his acquisition of a share in the New Willey Company. After Ann's death, at the age of 35, he married Mary Lee, whose financial resources helped him buy out his partners and consolidate control over his ventures. In his seventies, his mistress, Mary Ann Lewis, a maid at his estate in Brymbo Hall, gave birth to his only children: a boy and two girls.

By 1796, at 68 years old, Wilkinson's industrial empire had grown to an extraordinary scale, producing approximately one-eighth of Britain's entire cast iron output. He had become an immensely wealthy and somewhat eccentric "titan" of industry. His "iron madness" (鉄きちがいtetsu kichigaiJapanese) reached its peak in the 1790s, manifesting in an extreme affinity for the metal. He commissioned almost everything around him to be made of iron, including several coffins and a massive obelisk intended to mark his grave. This distinctive iron obelisk still stands today in the village of Lindale-in-Cartmel, now part of Cumbria.

5.2. Death and Estate Dispute

John Wilkinson died on 14 July 1808 at his works in Bradley, likely from diabetes. He was initially buried at his Castlehead estate near Grange-over-Sands, an area of marshland that he had drained and significantly improved from 1778 onwards. In his will, he left a very substantial estate valued at over 130.00 K GBP (equivalent to over 18.00 M GBP in 2023), which he intended to be primarily inherited by his three children, with executors appointed to manage the estate on their behalf.

However, his nephew, Thomas Jones, challenged the will in the Court of Chancery. The ensuing legal battles and poor management ultimately led to the substantial dissipation of the vast estate by 1828. Wilkinson's corpse, entombed in its distinctive iron coffin, was moved multiple times over the subsequent decades, and its current whereabouts are unknown.

6. Legacy and Assessment

John Wilkinson's life and work left an indelible mark on the industrial landscape, his legacy evaluated through his profound impact on technology, economy, and even social practices.

6.1. Impact on the Industrial Revolution

John Wilkinson's specific influence and contributions to the British Industrial Revolution were profound, particularly in the advancement of the iron industry and technological innovation. His invention of the precision boring machine was a critical enabler for James Watt's steam engines, solving a fundamental problem of cylinder accuracy and paving the way for the widespread adoption of steam power across various industries. This innovation is often credited as the first true machine tool, laying the groundwork for modern precision manufacturing.

Wilkinson was also a pioneer in the large-scale manufacture and diverse application of cast iron. His development of the hydraulic blowing engine significantly improved blast furnace efficiency, allowing for higher production rates and thus more affordable and abundant iron. He was instrumental in demonstrating the versatility of iron, from constructing the world's first cast-iron bridge, the Iron Bridge, to launching the first wrought iron barges. By 1796, his enterprises alone were responsible for producing approximately one-eighth of Britain's total cast iron output, a testament to his massive production scale and significant economic impact. He successfully integrated various stages of iron production, from mining raw materials to manufacturing finished products, creating a vertically integrated industrial empire that greatly contributed to Britain's emergence as an industrial powerhouse. His vision extended beyond simply making iron; he recognized the transformative potential of iron in new applications, from machinery to infrastructure, thereby driving the technological and economic momentum of the Industrial Revolution.

6.2. Criticisms and Controversies

While celebrated for his innovations, John Wilkinson's career and personal life were not without criticisms and controversies. A notable instance involved the quashing of his patent for boring cannons from a solid piece of metal in 1779. The Royal Navy viewed this patent as an attempt to establish a monopoly, arguing against the exclusive control of such vital technology. Despite Wilkinson's claims of improved accuracy and safety, the patent was overturned, reflecting a tension between innovation, proprietary rights, and public interest or strategic needs.

Furthermore, his personal affairs led to significant disputes following his death. The legal battles over his vast estate, primarily initiated by his nephew Thomas Jones, resulted in a protracted and costly struggle in the Court of Chancery. By 1828, a mere two decades after his passing, the once immense fortune he had accumulated was largely dissipated by the lawsuits and poor management of his assets. This dispute highlights the complexities of inheritance and wealth management in the early industrial era, and the vulnerability of even the most successful individuals' legacies to family conflict and legal entanglements.

7. Commemoration

John Wilkinson is commemorated by several enduring elements that reflect his unique personality and lasting impact on the industrial landscape. Most notably, a massive iron obelisk marks his grave in the village of Lindale-in-Cartmel, Cumbria. This monument is a direct testament to his "iron madness"-his peculiar obsession with the metal that defined his life and work.

His desire for an iron-centric existence extended even to his death; he was interred in a distinctive iron coffin. Although he was originally buried at his Castlehead estate, his corpse and its unusual coffin were moved several times over the decades following his death. Unfortunately, the ultimate fate of this specific iron coffin, and thus Wilkinson's remains, is now unknown, adding a layer of mystery to the legacy of this eccentric industrialist.